Abstract

Homeoproteins are defined by the structure of their DNA-binding domain, the homeodomain. Intercellular transfer of homeoprotein was observed ex vivo between animal cells and in vivo in higher plants. In the latter case, transfer is through intercytoplasmic channels that connect plant cells, but these do not exist in animals. Here, we show that the homeodomain of KNOTTED1, a maize homeoprotein, is transferred between animal cells and that a mutation in the homeodomain blocking the intercellular transfer of KNOTTED1 in plants also inhibits the transfer of the KNOTTED1 homeodomain in animal cells. This mutation decreases nuclear addressing, and its effect on nuclear import and intercellular transfer is reverted by the addition of an ectopic nuclear localization signal. We propose that, despite evolutionary distance and the differences in multicellular organization, similar mechanisms are at work for intercellular transfer of homeoprotein in plants and animals. Furthermore, our results suggest that, at least in animals, homeodomain secretion requires passage through the nucleus.

Keywords: homeodomain, homeoprotein, intercellular communication, plasmodesmata, secretion

Introduction

For transcription factors, intercellular transfer is an unexpected property. However, homeoproteins, despite their nuclear localization, hydrophilic behaviour and the lack of a classical secretion signal sequence, are transferred between animal cells ex vivo (Joliot et al, 1998). Even though in vivo passage has not been studied directly, two endogenous homeoproteins (Engrailed-1 and Engrailed-2) have been found in a secretory compartment in vivo (Joliot et al, 1997). These observations form the basis of the ‘messenger proteins' hypothesis (Prochiantz & Joliot, 2003), which stipulates a signalling function for homeoproteins. Intercellular transfer of animal homeoprotein involves two distinct internalization and secretion sequences (Derossi et al, 1996; Joliot et al, 1998), both of which are present in the homeodomain. Furthermore, homeoprotein secretion is regulated through protein phosphorylation, as shown for chick Engrailed-2 homeoprotein (cEn2; Maizel et al, 2002).

The possibility of in vivo intercellular transfer of endogenous maize homeoprotein KNOTTED1 (KN1) between the mesophyll and epiderm is raised by the fact that KN1 protein, but not its messenger RNA, is detected in the epidermis (Jackson et al, 1994). The intercellular transfer of KN1 is further supported by its non-cell-autonomous activity (Sinha & Hake, 1990) and can be directly visualized after microinjection (Lucas et al, 1995) or tissuespecific expression of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)–KN1 fusion protein (Kim et al, 2002). A general view is that KN1 transport uses symplasmic transfer through plasmodesmata, which are plantspecific intercytoplasmic channels that allow the passage of macromolecules between cells. Consequently, symplasmic transfer does not necessarily involve passage across a biological membrane. In plant and animal cells, homeoprotein transfer results in the accumulation of the intact protein in non-vesicular compartments in the recipient cells. We asked whether intercellular transfers of homeoprotein observed in the two phyla, with radically different multicellular organizations, could have some similarities.

Results

Animal cell transfer of maize KN1 homeodomain

We have focused our study on the homeodomain because it contains all the information necessary for intercellular transfer between animal cells (Joliot et al, 1998) and between plant cells (Kim et al, 2005). In addition, regulation of intercellular transfer of homeoprotein by extra-homeodomain sequences (Maizel et al, 2002) could interfere with the primary goal of this study. The homeodomain of KN1 (KNHD) belongs to the TALE homeodomain subclass (three-amino-acid loop extension) and is significantly different from the Engrailed homeodomain (ENHD; Fig 1A). Its behaviour was analysed in the animal model developed for the study of the intercellular transfer of ENHD (Joliot et al, 1998). A transfected HeLa fibroblast cell line that expresses the protein of interest was co-cultured with primary embryonic neurons, and the transfer was tested by accumulation of the protein in the neurons visualized with a Tau neuronal marker antibody. After 36 h, KNHD expressed in HeLa cells was transferred efficiently into co-cultured neurons (Fig 1B). A higher magnification of the neurons confirmed the intracellular localization of KNHD (Fig 1C). Therefore, despite the phylogenetic distance between plants and animals, KNHD shows intercellular transfer between animal cells.

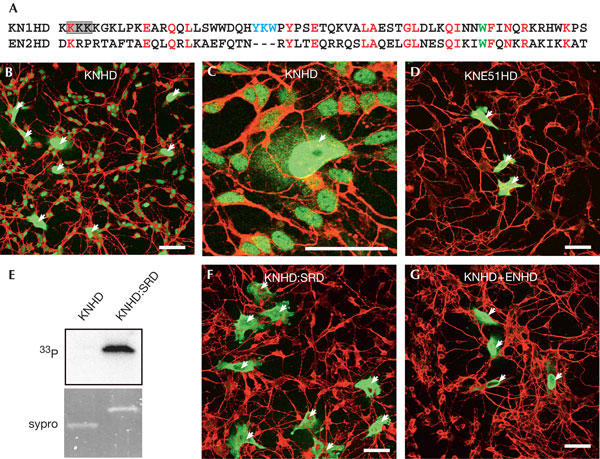

Figure 1.

The KN1 homeodomain is transferred from HeLa cells to neurons. (A) Sequence alignment of KNHD and ENHD. The Trp48 (in ENHD) is shown in green, the three-amino-acid loop extension in KNHD is blue and the amino acids substituted with alanines in the M6 mutant appear in a shaded box. (B,C) HeLa cells transfected with KNHD were co-cultured with rat embryonic neurons for 36 h. Fixed cells were immunostained with anti-haemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody for HA-tagged KNHD visualization (green) and anti-Tau antibody (red). KNHD is transferred efficiently between HeLa cells and neurons. (D) Intercellular transfer of KNE51HD, expressed in HeLa, is strongly impaired. (E,F) HeLa cells transfected with KNHD:SRD were labelled with 33P (E), or co-cultured with neurons (F). KNHD:SRD is highly phosphorylated (E) and its intercellular transfer was strongly impaired (F). (G) Coexpression of KNHD with ENHD (1:4 plasmid ratio) antagonizes the intercellular transfer of KNHD. The arrows represent transfected HeLa cells. Scale bars, 50 μm.

To verify that KNHD and animal homeoproteins use similar intercellular transfer pathways in animal cells, the effect of mutations that interfere with animal homeoprotein transfer was tested on KNHD. The tryptophan residue at position 48 of the homeodomain is crucial for the non-endocytic internalization of animal homeodomains (Joliot et al, 1991b; Le Roux et al, 1993; Derossi et al, 1994), and consequently for its intercellular transfer (Joliot et al, 1998). Indeed, the W → E mutation of the corresponding residue in KNHD (KNE51HD) abolished the transfer of the mutant homeodomain (Fig 1D). We then analysed the transfer of KNHD fused to the serine-rich domain (SRD) of Engrailed homeoprotein, a domain known to inhibit animal homeoprotein secretion through its phosphorylation (Maizel et al, 2002). The chimeric protein KNHD:SRD became phosphorylated (Fig 1E) and its transfer was markedly reduced (Fig 1F). We reasoned that if KNHD and Engrailed homeoprotein use the same transfer pathway, they should compete with each other for this process. As anticipated, when KNHD was coexpressed with a fourfold excess of ENHD (plasmid ratio), its transfer was strongly impaired (Fig 1G).

Effect of the M6 mutation in the animal model

If the transfer of KNHD observed in animals cells and plants involves related mechanisms, then mutations affecting this process should be active in both phyla. The M6 mutation (265KKK267 → AAA) in the amino-terminal part of KNHD is the only mutation that strongly inhibits the intercellular transfer of KN1 in planta, in both microinjection (Lucas et al, 1995) and in vivo expression protocols (Kim et al, 2002). The behaviour of KNHD bearing the M6 mutation (KNM6HD) was tested in an animal co-culture assay. Unlike wild-type KNHD (Fig 2A), KNM6HD was never detected in co-cultured neurons (Fig 2B), even though the two proteins were equally expressed (Fig 2G). Therefore, the same mutation that blocks intercellular transfer in planta also blocks ex vivo intercellular transfer between animal cells.

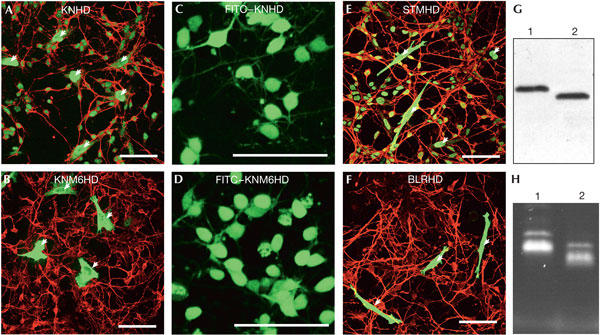

Figure 2.

M6 mutation inhibits secretion of the KN1 homeodomain. (A,B) HeLa cells transfected with KNHD (A) or KNM6HD (B) were processed as in Fig 1A. Compared with KNHD (A), KNM6HD (B) is not transferred in neurons. (C–F) Internalization of homeodomains in live embryonic neurons. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–KNHD (C,E) and FITC–KNM6HD (D,F) were added to the culture medium. After 1 h, live cells were analysed by confocal microscopy for FITC staining. The proteins were detected with similar intensities in neurons. (C,D) HeLa cells transfected with STMHD (C) or BLRHD (D) were processed as in Fig 1A. STMHD, but not BLRHD, is transferred in neurons. (G) Cellular extracts from HeLa cells expressing KNHD (lane 1) or KNM6HD (lane 2) that were used in (A) and (B), respectively, were analysed by western blot with an anti-haemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody. Both proteins are expressed at the same levels. (H) Fluorescence intensity of FITC–KNHD (lane 1) and FITC–KNM6HD (lane 2) that were used in (C) and (D), respectively. The arrows represent transfected HeLa cells. Scale bars, 50 μm.

The intercellular transfer of homeoprotein requires secretion and internalization. To determine which step is affected by the M6 mutation, we directly compared the internalization of KNHD and KNM6HD. Purified recombinant proteins were labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Fig 2H), and their internalization was monitored on live embryonic neurons by confocal microscopy. After a 1 h incubation, both proteins had efficiently accumulated in live neurons (Fig 2C,D), showing intense and comparable staining of the cell bodies. This shows that the blockade of KNHD transfer by the M6 mutations is at the level of secretion. It was recently shown that, as opposed to KN or Shootmeristemless (STM) homeodomain, some plant homeodomains, including the Bellringer (BLR) homeodomain, are not transferred in planta (Kim et al, 2005). The behaviour of the STM and BLR homeodomains was thus tested in the animal model. The transfer of STMHD was similar to that of KNHD (Fig 2E) but BLRHD was unable to transfer (Fig 2F). This reinforces the idea that homeodomain transfer in plants and in animals has a similar mechanism.

Role of the nucleus in homeodomain secretion

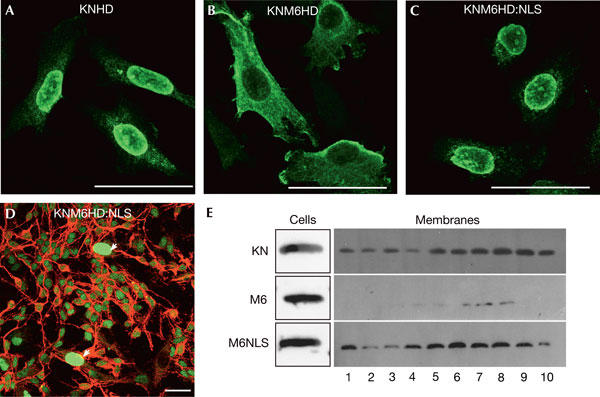

We observed that the M6 mutation strongly impairs nuclear accumulation of KNM6HD (Fig 3A,B). In fact, the M6 mutation removes a length of three lysine residues that may be part of a nuclear localization signal (NLS). We asked whether this effect could be linked to the absence of secretion of KNM6HD. After fusion of a canonical NLS (simian virus 40 (SV40) NLS) to the carboxyl terminus, the nuclear localization of the mutated homeodomain (KNM6HD:NLS) was fully restored (Fig 3C). Concomitantly, its transfer was also restored (Fig 3D), suggesting an unexpected link between secretion and passage through the nucleus. We then asked whether vesicular association of the homeodomains, a step preceding homeoprotein secretion (Joliot et al, 1998), was affected by the M6 mutation. As illustrated in Fig 3E, vesicular association of KNM6HD was strongly decreased compared with that of KNHD, although the proteins were expressed at similar levels, and was restored on NLS fusion to KNM6HD.

Figure 3.

Nuclear retargeting of an M6 mutant restores its intercellular transfer. (A–C) HeLa cells transfected with KNHD (A), KNM6HD (B) or KNM6HD:NLS (nuclear localization signal; C) were cultured for 24 h, fixed and immunostained with an anti-haemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody. Compared with KNHD (A) and KNM6HD:NLS (C), which mainly localize in the nucleus, KNM6HD accumulates in the cytoplasm (B). (D) HeLa cells transfected with KNM6HD:NLS were processed as in Fig 1A. Addition of an ectopic NLS to KNM6HD restores intercellular transfer. (E) Membrane fractions from cells transfected with the indicated constructs were separated on an Optiprep (10%–30%) density gradient and analysed by western blot with an anti-HA antibody. Although expressed at similar levels, KNM6HD is weakly detected in the different fractions compared with KNHD and KNM6HD:NLS (1, low density; 10, high density). The arrows represent transfected HeLa cells. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Discussion

The homeodomain of a plant homeoprotein is transferred efficiently between animal cells, in the absence of plasmodesmata. From competition and mutation experiments, it seems that cEN2 and KNHD use similar transfer mechanisms. This similarity was observed for internalization and secretion, as illustrated by the behaviour of KNHDE51 and KNHD:SRD. The conservation of intercellular transfer properties of the homeodomain could be indirect, simply reflecting strong evolutionary constraints associated with DNA-binding properties of the homeodomain. However, DNA-binding activity is not required for homeodomain transfer, at least for the internalization step (Le Roux et al, 1993). An alternative hypothesis is that the mechanisms of intercellular transfer have common properties in the two phyla. This idea is supported by the inhibitory effect of the same mutation on intercellular transfer of plant and animal homeoprotein and the similar behaviour of three plant homeodomains. Intercellular transfer might thus be an ancestral property of homeoproteins, conserved in evolution.

The inhibition of intercellular transfer of KNM6HD correlates with the increased cytoplasmic localization of the protein, and nuclear presence and secretion are restored on addition of a canonical NLS. This result is in agreement with our previous studies, showing that some homeoproteins shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and that a secretion-deficient mutant of cEN2 is also deficient for nuclear export (Joliot et al, 1998; Maizel et al, 1999). In addition, deletion of the KNHD NLS fully inhibits the transfer of the homeodomain in plants (Kim et al, 2005). The increased accumulation of KNM6HD:NLS in vesicular compartments, compared with KNM6HD, strongly suggests that vesicular addressing requires passage through the nucleus. Such an unexpected role of the nucleus has been described for the scaffold protein Ste5 in yeast. Indeed, Ste5 plasma membrane addressing depends on its nuclear accumulation (Mahanty et al, 1999). A positive correlation between nuclear accumulation and unconventional secretion has been reported in several cases (reviewed by Prochiantz & Joliot, 2003). For, instance, the phorbol ester phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate promotes both thioredoxin secretion (Sahaf & Rosen, 2000) and nuclear localization (Hirota et al, 1997). Similarly, N-terminal deletion abolishes galectin-3 secretion and nuclear accumulation (Gong et al, 1999). A possible explanation is that its passage through the nucleus renders the protein competent for secretion through post-translational modification and/or association with an unknown chaperone. In monocytes, hyperacetylation of the chromatin protein HMGB1 after stimulation promotes the nuclear export of the protein, followed by its secretion by acidic lysosomes (Bonaldi et al, 2003).

Speculation

The fact that plasmodesmata are essential components of intercellular communication in higher plants is not incompatible with the coexistence of various transfer modalities across these structures. A good example of this heterogeneity is the existence of conditions in which the transfer of small molecules (10 kDa FITC–dextran) or proteins (GFP, LEAFY) is inhibited, whereas other proteins, including KN1, are still transferred (Lucas et al, 1995; Kragler et al, 2000; Kim et al, 2002; Lee et al, 2003). The diffusion barrier created by the cell wall in plants may have led ancestral modes of intercellular communication to converge towards plasmodesmata, at the topological level. It is interesting that, similarly to KN1, members of the hsc70 and the thioredoxin families transfer through plasmodesmata (Ishiwatari et al, 1998; Aoki et al, 2002) and are secreted by animal cells (Rubartelli et al, 1992; Guzhova et al, 2001; Broquet et al, 2003), and even by bacteria in the case of thioredoxin (Bumann et al, 2002), despite their lack of a classical secretion signal sequence.

Methods

Plasmids. The homeodomain encoding sequence of the maize Knotted-1 gene (amino acids 263–326) was amplified by PCR and inserted into a PSG5 derivative plasmid, in-frame with an N-terminal haemagglutinin (HA) tag (MTSYPYDVPDYAAS). (The HA tag is not mentioned in the name of the constructs for simplicity.) M6 mutant (265KKK267 → AAA), E51 mutant (W316 → E) and SV40 NLS addition (PKKKRKV) were obtained by oligonucleotide insertion. For bacterial expression, KNHD or KNM6HD encoding sequence was cloned in a pGEX-1 derivative containing a scission site downstream of the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) encoding sequence.

Cell culture and transfection. HeLa cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Rat embryonic neurons were prepared and cultured as described previously (Joliot et al, 1998). For co-culture, HeLa cells (5 × 103) were cultured with freshly dissociated rat E16 cortical neurons (3.5 × 105) on glass coverslips coated with polyornithine (15 μg/ml) and fibronectin (10 μg/ml).

Immunofluorescence and microscopy. Cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (15 min at 20°C). HA-tagged homeodomains were detected with 3F10 antibody (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), followed by Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-rat antibody (Molecular Probes, Leiden, the Netherlands). Neurons were characterized by rabbit anti-Tau (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson, West Grove, PA, USA). All images were obtained using a confocal microscope (TCS, Leica, Wezlar, Germany). Pictures were acquired with constant integration parameters and processed using Adobe Photoshop.

Cell fractionation. Cellular extracts from transfected HeLa cells were prepared by dounce homogenization. Unbroken cells and nuclei were removed by low-speed centrifugation (at 1,000g for 10 min). After high-speed centrifugation (at 100,000g for 45 min), the pellet was resuspended in 40% Optiprep (Sigma) and loaded at the bottom of a 10%–30% Optiprep gradient in SW55 rotor. After centrifugation (at 70,000g for 2 h), 500 μl fractions were collected and concentrated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation. The pellets were dissolved in Laemmli buffer for western blot analysis.

Western blot. Protein samples were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (18%) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were incubated with rat monoclonal anti-HA antibody (3F10, 1/2,000; Roche) followed by biotinylated donkey anti-rat antibody (APB, Freiburg, Germany) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (APB). Signal was visualized with ECL+ (APB).

Recombinant protein expression and labelling. Recombinant proteins were purified from Escherichia coli BL21-RP cells (Stratagene) grown to an optical density (OD)600 of 0.5 and induced for 3 h at 28°C with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside. Proteins were purified on a GST HI-Trap column (APB) followed by in-column cleavage of the fusion protein with Pre-Scission protease (APB), as directed by the supplier. Purified proteins were conjugated to FITC as described previously (Joliot et al, 1991a).

Metabolic labelling and immunoprecipitation. Metabolic labelling was performed as described previously (Maizel et al, 2002). Proteins were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA matrix (Roche). Radioactivity was quantified by phosphorimaging.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr A. Prochiantz for his participation in many theoretical and practical aspects of this study and V. Lebled and Dr E. Dupont for their technical assistance. This work was supported by the Ecole Normale Supérieure, Centre National de la Rechecherche Scientifique and a grant from the European Community (HPRN-CT-2001-00242).

References

- Aoki K, Kragler F, Xoconostle-Cazares B, Lucas WJ (2002) A subclass of plant heat shock cognate 70 chaperones carries a motif that facilitates trafficking through plasmodesmata. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 16342–16347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaldi T, Talamo F, Scaffidi P, Ferrera D, Porto A, Bachi A, Rubartelli A, Agresti A, Bianchi ME (2003) Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. EMBO J 22: 5551–5560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broquet AH, Thomas G, Masliah J, Trugnan G, Bachelet M (2003) Expression of the molecular chaperone Hsp70 in detergent-resistant microdomains correlates with its membrane delivery and release. J Biol Chem 278: 21601–21606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumann D, Aksu S, Wendland M, Janek K, Zimny-Arndt U, Sabarth N, Meyer TF, Jungblut PR (2002) Proteome analysis of secreted proteins of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun 70: 3396–3403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G, Prochiantz A (1994) The third helix of Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol Chem 269: 10444–10450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derossi D, Calvet S, Trembleau A, Brunissen A, Chassaing G, Prochiantz A (1996) Cell internalization of the third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain is receptor-independent. J Biol Chem 271: 18188–18193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong HC, Honjo Y, Nangia-Makker P, Hogan V, Mazurak N, Bresalier RS, Raz A (1999) The NH2 terminus of galectin-3 governs cellular compartmentalization and functions in cancer cells. Cancer Res 59: 6239–6245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzhova I, Kislyakova K, Moskaliova O, Fridlanskaya I, Tytell M, Cheetham M, Margulis B (2001) In vitro studies show that Hsp70 can be released by glia and that exogenous Hsp70 can enhance neuronal stress tolerance. Brain Res 914: 66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K, Matsui M, Iwata S, Nishiyama A, Mori K, Yodoi J (1997) AP-1 transcriptional activity is regulated by a direct association between thioredoxin and Ref-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 3633–3638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwatari Y, Fujiwara T, McFarland KC, Nemoto K, Hayashi H, Chino M, Lucas WJ (1998) Rice phloem thioredoxin h has the capacity to mediate its own cell-to-cell transport through plasmodesmata. Planta 205: 12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, Veit B, Hake S (1994) Expression of maize KNOTTED1 related homeobox genes in the shoot apical meristem predicts patterns of morphogenesis in the vegetative shoot. Development 120: 405–413 [Google Scholar]

- Joliot A, Pernelle C, Deagostini-Bazin H, Prochiantz A (1991a) Antennapedia homeobox peptide regulates neural morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 1864–1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot AH, Triller A, Volovitch M, Pernelle C, Prochiantz A (1991b) α-2,8-Polysialic acid is the neuronal surface receptor of antennapedia homeobox peptide. New Biol 3: 1121–1134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot A, Trembleau A, Raposo G, Calvet S, Volovitch M, Prochiantz A (1997) Association of Engrailed homeoproteins with vesicles presenting caveolae-like properties. Development 124: 1865–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot A, Maizel A, Rosenberg D, Trembleau A, Dupas S, Volovitch M, Prochiantz A (1998) Identification of a signal sequence necessary for the unconventional secretion of Engrailed homeoprotein. Curr Biol 8: 856–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Yuan Z, Cilia M, Khalfan-Jagani Z, Jackson D (2002) Intercellular trafficking of a KNOTTED1 green fluorescent protein fusion in the leaf and shoot meristem of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 4103–4108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Rim Y, Wang J, Jackson D (2005) A novel cell-to-cell trafficking assay indicates that the KNOX homeodomain is necessary and sufficient for intercellular protein and mRNA trafficking. Genes Dev 19: 788–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragler F, Monzer J, Xoconostle-Cazares B, Lucas WJ (2000) Peptide antagonists of the plasmodesmal macromolecular trafficking pathway. EMBO J 19: 2856–2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux I, Joliot AH, Bloch-Gallego E, Prochiantz A, Volovitch M (1993) Neurotrophic activity of the Antennapedia homeodomain depends on its specific DNA-binding properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 9120–9124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Yoo BC, Rojas MR, Gomez-Ospina N, Staehelin LA, Lucas WJ (2003) Selective trafficking of non-cell-autonomous proteins mediated by NtNCAPP1. Science 299: 392–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas WJ, Bouché-Pillon S, Jackson DP, Nguyen L, Baker L, Ding B, Hake S (1995) Selective trafficking of KNOTTED1 homeodomain protein and its mRNA through plasmodesmata. Science 270: 1980–1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanty SK, Wang Y, Farley FW, Elion EA (1999) Nuclear shuttling of yeast scaffold Ste5 is required for its recruitment to the plasma membrane and activation of the mating MAPK cascade. Cell 98: 501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maizel A, Bensaude O, Prochiantz A, Joliot A (1999) A short region of its homeodomain is necessary for Engrailed nuclear export and secretion. Development 126: 3183–3190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maizel A, Tassetto M, Filhol O, Cochet C, Prochiantz A, Joliot A (2002) Engrailed homeoprotein secretion is a regulated process. Development 129: 3545–3553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochiantz A, Joliot A (2003) Can transcription factors function as cell–cell signalling molecules? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 814–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubartelli A, Bajetto A, Allavena G, Wollman E, Sitia R (1992) Secretion of thioredoxin by normal and neoplastic cells through a leaderless secretory pathway. J Biol Chem 267: 24161–24164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahaf B, Rosen A (2000) Secretion of 10-kDa and 12-kDa thioredoxin species from blood monocytes and transformed leukocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal 2: 717–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N, Hake S (1990) Mutant characters of knotted maize leaves are determined in the innermost tissue layers. Dev Biol 141: 203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information