Abstract

The African trypanosome, Trypanosoma brucei, is a flagellated pathogenic protozoan that branched early from the eukaryotic lineage. Unusually, it uses RNA polymerase I (Pol I) for mono-telomeric expression of variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) genes in bloodstream-form cells. Many other subtelomeric VSG genes are reversibly repressed, but no repressive DNA sequence has been identified in any trypanosomatid. Here, we show that artificially seeded de novo telomeres repress Pol I-dependent gene expression in mammalian bloodstream and insect life-cycle stages of T. brucei. In a telomeric VSG expression site, repression spreads further along the chromosome and this effect is specific to the bloodstream stage. We also show that de novo telomere extension is telomerase dependent and that the rate of extension correlates with the expression level of the adjacent gene. Our results show constitutive telomeric repression in T. brucei and indicate that an enhanced, developmental stage-specific repression mechanism controls antigenic variation.

Keywords: antigenic variation, silencing, trypanosome, variant surface glycoprotein

Introduction

Silent genes encoding variant surface molecules have a striking subtelomeric arrangement in several pathogens that undergo antigenic variation (reviewed by Barry et al, 2003), whereas telomeric DNA is known to induce local gene repression in yeast (Gottschling et al, 1990; Nimmo et al, 1994), Drosophila (Levis et al, 1985) and humans (Baur et al, 2001). Generally, these effects spread only a short distance from the telomere, but in some cases, repression has an impact on native genes, such as the mating-type loci in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Maillet et al, 1996) and genes encoding variant surface antigens involved in adhesion in S. cerevisiae (Halme et al, 2004) and in the pathogenic yeast, Candida glabrata (De Las Penas et al, 2003).

Trypanosomatids branched early from the eukaryotic lineage and gave rise to several important pathogens including Trypanosoma brucei. These flagellated protozoa are spread between mammals by tsetse flies and cause human African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness, and a cattle disease known as Nagana. They escape elimination by the host immune response through a continual process of antigenic variation that relies on a sophisticated mechanism of variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) gene expression. Of up to 2000 VSGs and VSG fragments in the genome, essentially all are subtelomeric such that most, if not all, telomeres seem to be occupied by VSGs. There are two principal subsets of VSG promoters. The ‘metacyclic' set, typically within ∼5 kbp of telomeres, operates during the earliest phase of an infection, whereas the ‘bloodstream' set, ∼50 kbp from telomeres, operates later during infection (Barry et al, 2003). Although there are ∼40 VSG promoters per cell, expression is monoallelic in bloodstream-form cells (reviewed by Barry et al, 2003).

Gene expression has unusual features in trypanosomatids. Polycistronic transcription is widespread and every messenger RNA has an identical trans-spliced leader. This polymerase II (Pol II) transcript (Gilinger & Bellofatto, 2001) provides a 5′ cap such that other polymerases may produce the remainder of the mRNA. Indeed, VSG genes are transcribed by Pol I, a polymerase confined to ribosomal RNA (RRNA) in other eukaryotes (Gunzl et al, 2003). The single active telomeric VSG localizes to an ‘expression site body', an extranucleolar structure enriched in Pol I (Navarro & Gull, 2001), and limited occupancy within this structure has been proposed to restrict VSG expression (reviewed by Borst, 2002). The system is reminiscent of odorant receptor choice in olfactory sensory neurons (Li et al, 2004), but in T. brucei, rather than a ‘one-protein rule' a ‘one-telomere rule' seems to operate. Thus, the active VSG is always adjacent to a telomere. Although a second VSG inserted at the active expression site can be coexpressed (Muñoz-Jordán et al, 1996), simultaneous activation of two telomeres does not seem to be possible (Chaves et al, 1999). We have explored the relationship between gene repression and telomeric location in T. brucei. We show that telomeres repress Pol I transcription locally. Repression is enhanced within a VSG expression site, specifically in the life-cycle stage that undergoes antigenic variation.

Results

De novo telomeres at VSG expression sites

In T. brucei, DNA rearrangement occurs almost exclusively by homologous recombination, and DNA fragments with terminal G-rich sequences can seed de novo telomeres (Horn et al, 2000), facilitating targeted chromosome fragmentation. The telomere-mediated fragmentation construct used here (pTMF; Fig 1A) can be cleaved to generate an array of T2AG3 repeats or a short G-rich sequence immediately adjacent to a double-strand break, and both of these ‘telomere seeds' allow reproducible generation of de novo telomeres in T. brucei (Horn et al, 2000). Thus, we can use pTMF to generate de novo telomeres at two different positions. Also, an RRNA promoter (Schimanski et al, 2004) driving NPT expression permits selection of cells that express NPT at only a low level (Horn & Cross, 1997b). The RRNA promoter recruits Pol I, as does the VSG promoter (Gunzl et al, 2003). Indeed, it can replace the VSG promoter and can still be switched on and off during antigenic variation in bloodstream-form cells (Rudenko et al, 1995). Thus, the RRNA promoter will reflect the presence or absence of Pol I cofactor-binding platforms.

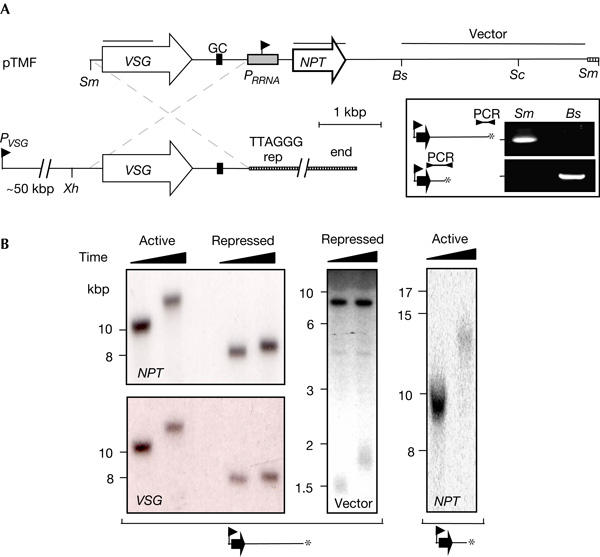

Figure 1.

De novo telomeres at VSG loci. (A) The polycistronic VSG expression site extends from the VSG promoter (PVSG) to several kilobase pairs of terminal T2AG3 repeats. pTMF, cut with SmaI (Sm) or SmaI plus Bsp120I (Bs), can be used to replace the native telomere with telomere seeds 5 and 2 kbp from the RRNA promoter (PRRNA), respectively. ‘GC' indicates the location of a conserved GC-rich element (see below). PCR assays using a T2AG3 repeat primer and an internal primer (see Methods) indicate that de novo telomeres are generated at the expected locations (inset). (B) De novo telomere extension. DNA extracted from cells 20 generations after transfection and a month later was digested with XhoI (Xh) or XhoI plus ScaI (Sc; middle panel) before Southern blotting. The probes (see the pTMF map in (A)) used for hybridization are indicated on the blots. Similar hybridization patterns with NPT or VSG probes confirm integration at the VSG locus.

We first generated de novo telomeres that replaced the native telomere at an active VSG locus (Fig 1A). A PCR assay was used to show that telomeres can be engineered 5 or 2 kbp from the promoter (Fig 1A, inset; the expected PCR products are illustrated; the cartoons shown are used throughout to illustrate promoter/telomere spacing). The extra 3 kbp of sequence in the ‘5 kbp' cells is a plasmid vector sequence and there is no evidence that this DNA can block repression in T. brucei (see below) or in other cell types. Using another cell line expressing a VSG on another chromosome, we generated telomeres adjacent to a silent copy of the same VSG gene, as above.

In T. brucei, the number of telomeric DNA repeats at the chromosome end is not strictly regulated, but the rate of extension is normally limited to 8 bp per generation (Pays et al, 1983). Southern blotting indicates that the NPT gene is linked to the VSG gene as expected, and that adjacent de novo telomeres are rapidly extended when the active locus is targeted (Horn et al, 2000), but are slowly extended when the repressed locus is targeted (Fig 1B; see below).

Telomerase-dependent de novo telomere extension

Next, we determined whether the pTMF construct could be used to generate terminal truncations and de novo telomeres elsewhere in the genome. The RRNA promoter in the fragmentation construct may also serve as a targeting fragment. Thus, we targeted the NPT reporter cassette to RRNA loci (Fig 2A). PCR assays again indicated that de novo telomeres were generated at defined distances from the promoter (Fig 2A, inset). Four independent clones were generated for further analysis, two with telomeres about 5 kbp from the promoter (R5a and R5b) and two with telomeres about 2 kbp from the promoter (R2a and R2b). As expected, Southern blotting indicated that telomeres formed at RRNA loci are not linked to VSG (Fig 2B, left panels).

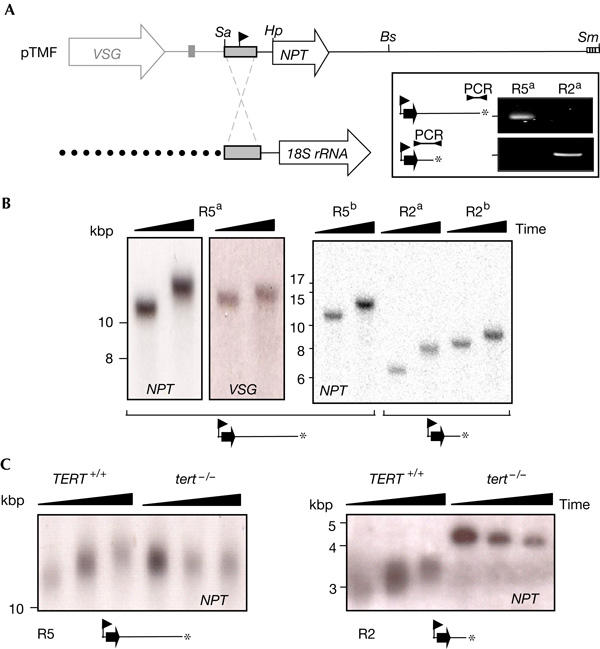

Figure 2.

De novo telomeres at RRNA loci and telomere shrinkage after TERT disruption. (A) pTMF cut with SalI (Sa) is targeted to RRNA. As in Fig 1, another cut at SmaI (Sm) or Bsp120I (Bs) generates telomere seeds 5 and 2 kbp from the promoter, respectively. A PCR assay indicates that telomeres are generated as expected (inset). Hp, HpaI. (B,C) Southern blotting was carried out as in Fig 1B. (B) De novo telomere extension. Different hybridization patterns with NPT or VSG probes (left panels) confirm that the NPT gene is not linked to the VSG locus in these cells. (C) TERT disruption leads to telomere shrinkage. Genomic DNA was extracted at intervals of ∼20 cell doublings before and after TERT disruption and was then digested with HpaI before Southern blotting.

To determine whether de novo telomeres were extended by a telomerase-dependent mechanism, we identified the putative telomerase reverse-transcriptase (TERT) gene in the T. brucei genome sequence. Both alleles of the gene were disrupted by deletion of the portion encoding residues 222–961 in R5 and R2 de novo telomere cells and in otherwise unmodified cells. Correct disruption was confirmed in all three cell types using a PCR assay (data not shown). We were unable to generate de novo telomeres in cells lacking TERT (data not shown), which suggested that initial telomere seeding is TERT dependent. Examination of both R5 and R2 cells indicated that telomeres are extended before TERT disruption, whereas length diminishes after TERT disruption (Fig 2C). This can be seen more clearly at the shorter R2 telomere (Fig 2C, right panel) in which length is uniformly reduced in the population. Telomere loss in these cells is consistent with the recently reported rate of loss of ∼4 bp per cell division at native telomeres in the absence of TERT (Dreesen et al, 2005). We conclude that both de novo telomere seeding and subsequent extension are TERT dependent.

De novo telomeres support VSG regulation

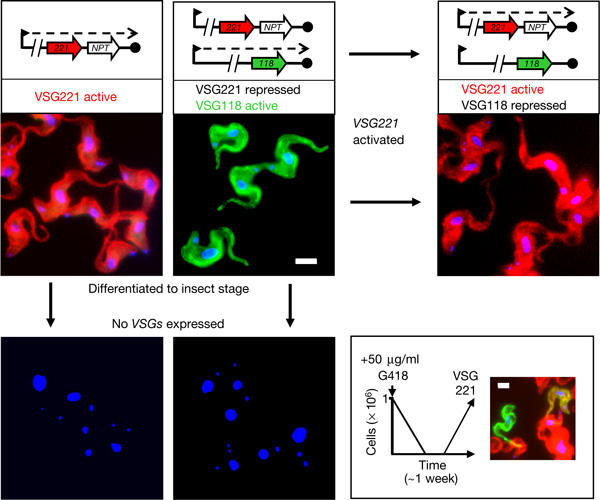

We first analysed VSG expression in clones with de novo telomeres at VSG221 loci. First, immunofluorescence analysis, using VSG antisera, indicated that active and silent VSG221 genes maintain their expression status when fused to de novo telomeres (Fig 3, top left). In a previous work, selection for cells with increased NPT expression indicated that antigenic variation and coactivation of a selectable marker proximal to a native telomere occurred in <1 × 106 cells per division (Horn & Cross, 1997a). Cells that activate the current de novo telomere-associated VSG could be similarly selected (Fig 3, right-hand side). In insect-stage cells, VSG is not normally expressed. After differentiation to this stage, VSG genes did not produce any detectable VSG surface labelling irrespective of their prior expression status (Fig 3, bottom left). Thus, de novo telomeres do not interrupt VSG expression or repression, VSG activation during antigenic variation or VSG regulation during differentiation.

Figure 3.

De novo telomeres support VSG regulation. Schematic maps indicate VSG transcription (dashed line) in bloodstream-form cells with de novo telomeres at active and repressed VSG expression sites. Immunofluorescence signals representing VSG221 (red), VSG118 (green) and DNA (blue) were merged in all images. Scale bar, 5 μm. The box at the bottom right-hand corner shows a schematic ‘growth curve', illustrating how antigenically variant cells were selected, and a control for detection of cells expressing VSG118 (green), VSG221 (red) or both (yellow).

Telomeni and VSG-associated repression

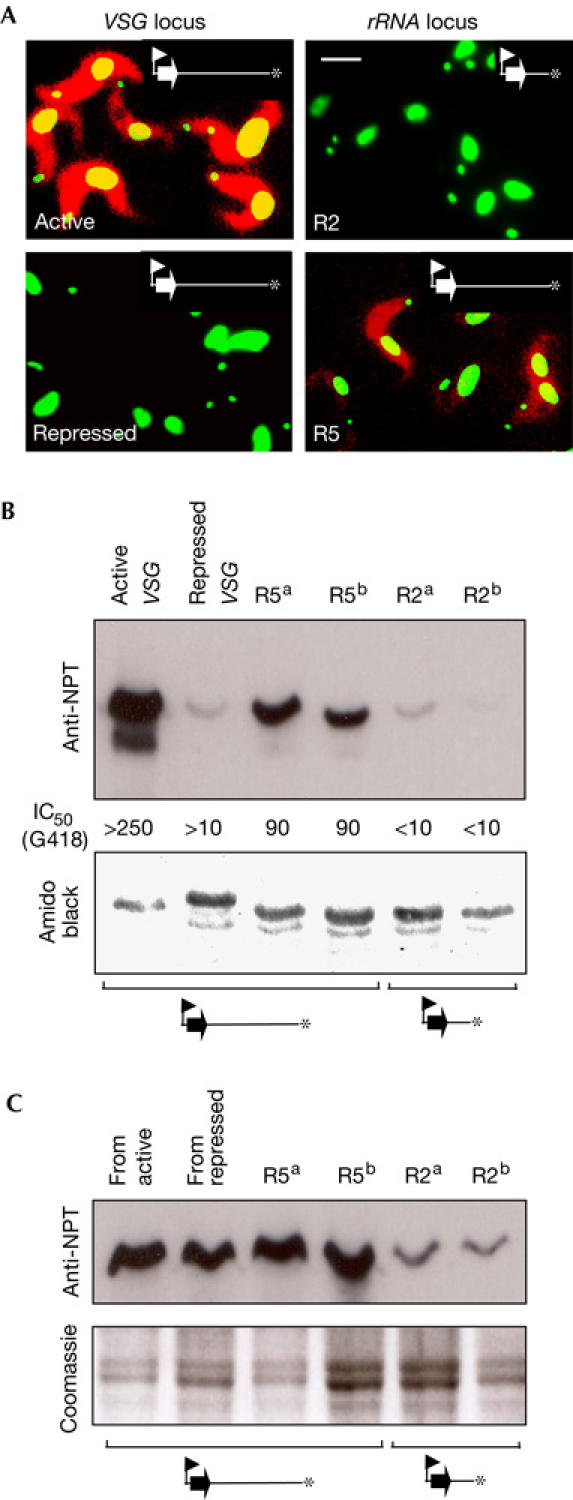

We next examined the influence of telomere proximity on NPT reporter expression using three different assays: immunofluorescence analysis, western blotting and G418 growth-inhibitory concentration (IC50) analysis. Immunofluorescence analysis indicated that NPT expression mirrored VSG expression at active and repressed VSG loci (Fig 4A, left panels). An examination of reporter expression at RRNA loci indicated that the R2 population (Fig 4A, top right panel) consistently expressed NPT at a low level but that expression was increased when the reporter was further from the telomere, as in R5 cells (bottom right panel). Although heterogeneous, NPT expression was consistently higher in most R5 cells relative to R2 cells. Similar results were obtained following G418 selection or further telomere extension (data not shown). An NPT western blot assay and IC50 assays (Fig 4B) confirmed that NPT expression is inversely proportional to telomere proximity (compare R5 and R2 lanes). Taken together, the data suggest that telomeric repression is rapidly diminished only a short distance from the telomere at RRNA loci. In contrast to repression at RRNA loci, repression at a VSG locus is strong when the promoter is 5 kbp from the telomere (Fig 4B, compare repressed VSG and R5 lanes). Indeed, repression within a VSG expression site was previously shown to extend over a greater distance (Horn & Cross, 1997b). We conclude that telomeres mediate repression independent of expression site context, and that additional repression operates within VSG expression sites.

Figure 4.

Telomeric and VSG expression site-associated repression. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of bloodstream-form cells. Images representing NPT (red) and DNA (green) were merged. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B,C) Western blotting using anti-NPT II as a primary antibody. VSG on the blot, stained with amido black (B), or an equivalent gel stained with Coomassie blue (C), provides a loading control. (B) Analysis of bloodstream-form cell extracts. Corresponding IC50 values (μg/ml) are shown. (C) Analysis of insect-stage cell extracts.

Repression adjacent to VSG genes at native telomeres is developmentally regulated and seems to be bloodstream-form specific (Horn & Cross, 1995). Our analysis indicated that this was also the case in an expression site with a de novo telomere (Fig 4C). Thus, VSG expression site-associated repression, which is strong at 5 kbp from the telomere in the bloodstream form, was abolished in insect-stage cells and the expression level was the same whether the NPT gene was linked to the previously active or silent VSG gene (compare ‘from active' and ‘from repressed' in Fig 4C with ‘active VSG' and ‘repressed VSG' in Fig 4B, respectively). In striking contrast, telomeric repression, within 2 kbp of the telomere, continued to operate when cells were differentiated to the insect stage (Fig 4C, compare R5 and R2 lanes). Thus, VSG expression site-associated repression is bloodstream-form specific whereas telomeric repression is constitutive.

Telomere extension rate correlates with gene expression

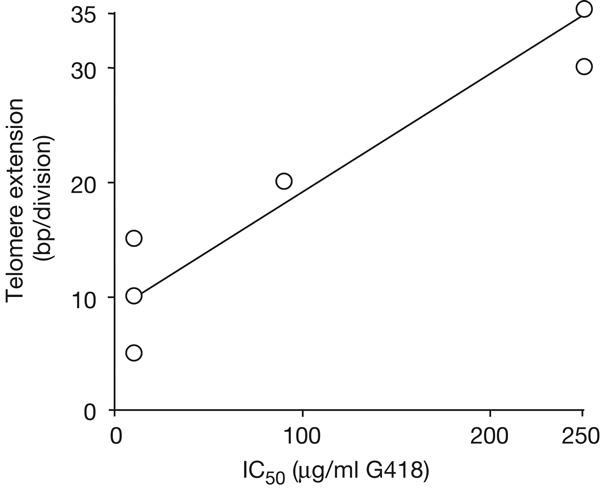

Telomere extension at native telomeres, whether associated with silent or active VSG genes, is limited to about 8 bp per cell division (Pays et al, 1983). To examine the relationship between TERT-dependent de novo telomere extension and gene expression, we estimated approximate extension rates from our Southern blot data (Figs 1B and 2B) and plotted these against IC50 values (Fig 3B) for the corresponding cells. The analysis shows that the rate of telomere extension correlates with adjacent gene expression level (Fig 5).

Figure 5.

De novo telomere extension rate correlates with gene expression.

Discussion

No cis- or trans-acting repressor has been previously identified in a trypanosomatid. Here, we report cis-acting repression of Pol I transcription emanating from telomeric DNA in T. brucei. Our results greatly extend the phylogenetic range of organisms that show telomeric gene repression, suggesting either that this phenomenon had an ancient origin or that it is a general feature of chromosome ends. Similar to the situation in S. cerevisiae, basal telomeric repression seems to be confined to a relatively limited telomeric domain. In bloodstream-form cells, however, in which VSG repression is crucial to the survival of the parasite, repression extends further. This developmentally regulated spread of repression may represent an elaboration of ‘simple' telomeric repression, but at this stage we cannot rule out the possibility that telomeric silencing and VSG expression site silencing are mechanistically distinct.

In S. cerevisiae, a specialized chromatin structure represses Pol II genes inserted at telomeres, mating-type loci or RRNA. At telomeres, transcription is blocked by repressive machinery recruited to the telomere and propagated further along the DNA. Nucleosomes modified by repressors allow transcription factors to access the DNA, but they block promoter clearance or transcription elongation (reviewed by Rusche et al, 2003). A similar mechanism is involved in silencing variant surface antigen genes up to 55 kbp from the telomere in Plasmodium falciparum (reviewed by Ralph & Scherf, 2005). Such a mechanism may also act on Pol I in T. brucei.

The current results also show that the rate of telomerase-dependent de novo telomere extension is proportional to the level of local gene expression (when a promoter is directed towards the telomere). Irrespective of length, telomere extension is limited to ∼8 bp per cell division at transcriptionally silent T. brucei telomeres. In contrast, at the active expression site, extension is slightly faster at native telomeres (Pays et al, 1983) and initially much faster at de novo telomeres but inversely proportional to telomere length (Horn et al, 2000). We suggest a negative feedback mechanism for telomere length control at the active locus, whereby transcription increases exposure to the action of telomerase. The effect would be diminished as the terminus or terminal t-loop (Muñoz-Jordán et al, 2001) moves further from the promoter, possibly owing to transcription attenuation brought about by DNA base modification found in T. brucei telomeric DNA (van Leeuwen et al, 1998). This model is consistent with transcription of T2AG3 repeats in T. brucei (Rudenko & van der Ploeg, 1989) and may explain relatively large increases in telomere length seen at activated expression sites (Myler et al, 1988). A similar model could explain longer than average telomeres at truncated chromosomes in the malaria parasite, P. falciparum (Figueiredo et al, 2002), but transcription does not correlate with the increased preference of telomerase for shorter telomeres seen in S. cerevisiae (Sandell et al, 1994; Teixeira et al, 2004).

We have shown telomeric repression of RNA Pol I transcription in T. brucei. Our data also indicate pronounced repression associated with VSG expression sites, a developmentally regulated effect likely to have a specific role in antigenic variation. In yeasts, native subtelomeric sequences generally limit the spread of repression (Pryde & Louis, 1999), but silencing can be propagated by subtelomeric relay elements to control the expression of a subset of genes (Maillet et al, 1996; De Las Penas et al, 2003; Halme et al, 2004). A similar propagation mechanism may operate in T. brucei. A potential T. brucei telomere-associated ‘relay' element retained at the VSG-associated de novo telomeres described here is the GC-rich element (location indicated in Fig 1). This element contains a highly conserved T2AG3 repeat-related core and is found between VSG genes and terminal T2AG3 repeats within all subtelomeres examined so far (Horn & Barry, 2005). Thus, the potential for gene repression at T. brucei telomeres may have been usurped for VSG gene silencing to facilitate monoallelic VSG expression and antigenic variation. Further genome manipulation should allow us to determine whether telomeres and/or GC-rich elements are involved in VSG expression site repression, and genome sequence data (Berriman et al, 2005) should facilitate identification of trans-acting repressors.

Methods

Cells. Bloodstream-form T. brucei cells of the Lister 427 strain, clone 221a (MITat 1.2) and clone 118a (MITat 1.5), were maintained, cloned, genetically modified and differentiated, as described previously (Horn & Cross, 1997a).

Plasmid construction. See the supplementary information online.

DNA analysis. PCR assays were carried out using the Tel2 primer (5′-acccta-3′)5 paired with either NEO3 (5′-cgccttcttgacgagttct-3′) or Vheal (5′-cccactacgtgaaccatca-3′) primers, as described (Horn et al, 2000). A month of continuous culture represents approximately 50 generations for 118a cells and 100 generations for 221a cells.

Protein analysis. Primary anti-NPT-II was from Europa Bioproducts Ltd (Cambridge, UK). Antisera for VSG immunofluorescence were rat anti-VSG221 and mouse anti-VSG118. Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/7400575-s1.pdf).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Sabatini, S. Alsford, J. Kelly, M. Taylor and N. Dorrell for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank G. Cross for the valuable gift of antibodies against well-characterized VSGs. This work was supported by a Research Career Development Fellowship to D.H. (052323) and a project grant (069909) from The Wellcome Trust.

References

- Barry JD, Ginger ML, Burton P, McCulloch R (2003) Why are parasite contingency genes often associated with telomeres? Int J Parasitol 33: 29–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur J, Zou Y, Shay J, Wright W (2001) Telomere position effect in human cells. Science 292: 2075–2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriman M et al. (2005) The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science 309: 416–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst P (2002) Antigenic variation and allelic exclusion. Cell 109: 5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves I, Rudenko G, Dirks Mulder A, Cross M, Borst P (1999) Control of variant surface glycoprotein gene-expression sites in Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J 18: 4846–4855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Las Penas A, Pan SJ, Castano I, Alder J, Cregg R, Cormack BP (2003) Virulence-related surface glycoproteins in the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata are encoded in subtelomeric clusters and subject to RAP1- and SIR-dependent transcriptional silencing. Genes Dev 17: 2245–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreesen O, Li B, Cross GAM (2005) Telomere structure and shortening in telomerase-deficient Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 4536–4543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo LM, Freitas-Junior LH, Bottius E, Olivo-Marin JC, Scherf A (2002) A central role for Plasmodium falciparum subtelomeric regions in spatial positioning and telomere length regulation. EMBO J 21: 815–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilinger G, Bellofatto V (2001) Trypanosome spliced leader RNA genes contain the first identified RNA polymerase II gene promoter in these organisms. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 1556–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschling DE, Aparicio OM, Billington BL, Zakian VA (1990) Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of pol II transcription. Cell 63: 751–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzl A, Bruderer T, Laufer G, Schimanski B, Tu LC, Chung HM, Lee PT, Lee MG (2003) RNA polymerase I transcribes procyclin genes and variant surface glycoprotein gene expression sites in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot Cell 2: 542–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halme A, Bumgarner S, Styles C, Fink GR (2004) Genetic and epigenetic regulation of the FLO gene family generates cell-surface variation in yeast. Cell 116: 405–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn D, Barry JD (2005) The central roles of telomeres and subtelomeres in antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. Chromosome Res 13: 525–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn D, Cross GAM (1995) A developmentally regulated position effect at a telomeric locus in Trypanosoma brucei. Cell 83: 555–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn D, Cross GAM (1997a) Analysis of Trypanosoma brucei VSG expression site switching in vitro. Mol Biochem Parasitol 84: 189–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn D, Cross GAM (1997b) Position-dependent and promoter-specific regulation of gene expression in Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J 16: 7422–7431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn D, Spence C, Ingram AK (2000) Telomere maintenance and length regulation in Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J 19: 2332–2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis R, Hazelrigg T, Rubin GM (1985) Effects of genomic position on the expression of transduced copies of the white gene of Drosophila. Science 229: 558–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ishii T, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P (2004) Odorant receptor gene choice is reset by nuclear transfer from mouse olfactory sensory neurons. Nature 428: 393–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillet L, Boscheron C, Gotta M, Marcand S, Gilson E, Gasser SM (1996) Evidence for silencing compartments within the yeast nucleus: a role for telomere proximity and Sir protein concentration in silencer-mediated repression. Genes Dev 10: 1796–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Jordán JL, Davies KP, Cross GAM (1996) Stable expression of mosaic coats of variant surface glycoproteins in Trypanosoma brucei. Science 272: 1795–1797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Jordán JL, Cross GAM, de Lange T, Griffith JD (2001) t-loops at trypanosome telomeres. EMBO J 20: 579–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myler PJ, Aline RF, Scholler JK, Stuart KD (1988) Changes in telomere length associated with antigenic variation in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol 29: 243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M, Gull K (2001) A polI transcriptional body associated with VSG mono-allelic expression in Trypanosoma brucei. Nature 414: 759–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmo ER, Cranston G, Allshire RC (1994) Telomere-associated chromosome breakage in fission yeast results in variegated expression of adjacent genes. EMBO J 13: 3801–3811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pays E, Laurent M, Delinte K, vanMeirvenne N, Steinert M (1983) Differential size variations between transcriptionally active and inactive telomeres of Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res 11: 8137–8147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryde FE, Louis EJ (1999) Limitations of silencing at native yeast telomeres. EMBO J 18: 2538–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph SA, Scherf A (2005) The epigenetic control of antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. Curr Opin Microbiol 8: 434–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenko G, van der Ploeg LH (1989) Transcription of telomere repeats in protozoa. EMBO J 8: 2633–2638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenko G, Blundell PA, Dirks-Mulder A, Kieft R, Borst P (1995) A ribosomal DNA promoter replacing the promoter of a telomeric VSG gene expression site can be efficiently switched on and off in T. brucei. Cell 83: 547–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusche LN, Kirchmaier AL, Rine J (2003) The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 481–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell LL, Gottschling DE, Zakian VA (1994) Transcription of a yeast telomere alleviates telomere position effect without affecting chromosome stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 12061–12065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimanski B, Laufer G, Gontcharova L, Gunzl A (2004) The Trypanosoma brucei spliced leader RNA and rRNA gene promoters have interchangeable TbSNAP50-binding elements. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 700–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira MT, Arneric M, Sperisen P, Lingner J (2004) Telomere length homeostasis is achieved via a switch between telomerase-extendible and -nonextendible states. Cell 117: 323–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen F, Kieft R, Cross M, Borst P (1998) Biosynthesis and function of the modified DNA base β-D-glucosyl-hydroxymethyluracil in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Cell Biol 18: 5643–5651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information