Abstract

Objective

To compare the 10 year risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and combined cardiovascular disease (CVD) estimated from the Framingham equations.

Design

Population based cross sectional survey.

Setting

Nine general practices in south London.

Population

1386 men and women, age 40-59 years, with no history of CVD (475 white people, 447 south Asian people, and 464 people of African origin), and a subgroup of 1069 without known diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, peripheral vascular disease, renal impairment, or target organ damage.

Main outcome measures

10 year risk estimates.

Results

People of African origin had the lowest 10 year risk estimate of CHD adjusted for age and sex (7.0%, 95% confidence interval 6.5 to 7.5) compared with white people (8.8%, 8.2 to 9.5) and south Asians (9.2%, 8.6 to 9.9) and the highest estimated risk of stroke (1.7% (1.5 to 1.9), 1.4% (1.3 to 1.6), 1.6% (1.5 to 1.8), respectively). The estimate risk of combined CVD, however, was highest in south Asians (12.5%, 11.6 to 13.4) compared with white people (11.9%, 11.0 to 12.7) and people of African origin (10.5%, 9.7 to 11.2). In the subgroup of 1069, the probability that a risk of CHD ⩾15% would identify risk of combined CVD ⩾20% was 91% in white people and 81% in both south Asians and people of African origin. The use of thresholds for risk of CHD of 12% in south Asians and 10% in people of African origin would increase the probability of identifying those at risk to 100% and 97%, respectively.

Conclusion

Primary care doctors should use a lower threshold of CHD risk when treating mild uncomplicated hypertension in people of African or south Asian origin.

Introduction

The prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) now relies on the reduction of the overall absolute risk of disease rather than management of individual risk factors.1 The strategy for primary prevention in people with no history of CVD is to estimate the absolute risk of a vascular event and to take appropriate action according to that level of risk.2–4 British hypertension guidelines suggest that people with moderate blood pressure (140-159/90-99 mm Hg) but no target organ damage, cardiovascular complications, or diabetes should be treated if their 10 year risk of CHD (myocardial infarction, death from other CHD, angina, and coronary insufficiency) is ⩾15%.3 This assumes that the risk of combined CVD (risk of CHD plus stroke, transient ischaemic attack, congestive cardiac failure, and peripheral vascular disease) may be obtained by multiplying the estimated 10 year risk of CHD by 4/3 (for example, 15% risk of CHD=20% risk of CVD).5 The risk estimation is based on the 10 year prospective experience of the Framingham cohort, white middle class men and women, aged 30-74 years, living in semiurban Massachusetts. Compared with white people, people of African origin have less CHD but more hypertension, diabetes, strokes, and renal failure, and south Asians have more hypertension, diabetes, central obesity, and CHD.6,7

The estimate of risk with the Framingham equation may not accurately estimate the risk of vascular disease in some ethnic minorities.2,3 In addition, the equivalence between the risk of CHD and the risk of CVD may not apply. Given the lack of prospective data in large ethnically mixed populations in the United Kingdom, however, these risk equations are the best available tools to guide the decision making process of prevention in general practice. However, we do not know what impact this approach may have on the management of hypertension in selected ethnic groups. We compared the estimated risks of CHD, stroke, and combined CVD in a general practice sample of white people, south Asians, and people of African origin from south London and looked at the implications of using these risk estimates.

Methods

The survey methods are described in detail elsewhere.7,8 Briefly, we recruited men and women aged 40-59 years from nine general practices in Wandsworth, south London, where about a quarter of the residents are from ethnic minorities. Participants likely to be of south Asian or west African origin were identified by family name, while Afro-Caribbeans were identified by general practitioners and receptionists. We also invited a random sample of white patients to yield an equal number of participants in each ethnic group. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and all participants gave informed consent. Fieldwork was undertaken from March 1994 to July 1996. Ethnic group was recorded at the time of interview on the basis of answers to a combination of questions including place and country of birth, language, religion, history of migration, and parents' country of birth.7,8

The overall response rate to invitations was 64%.8 Of the 1577 participants screened, we excluded 119 because of missing values for any of the risk factors used in the Framingham equations and 72 because of pre-existing CHD or stroke. This left 1386 participants (475 white people, 447 south Asian, and 464 of African origin). There were 760 (55%) women.

After an overnight fast participants attended a dedicated screening unit between 8 am and noon. Blood pressure was taken with standardised methods.7,8 Participants not known to be diabetic and without glycosuria underwent a standard oral glucose tolerance test.7,8 Blood samples were taken for full lipid profile. Participants were classified as smokers if they were currently smoking one or more cigarettes, cigars, or pipes on a regular daily basis. Diabetes was defined according to both the new American Diabetes Association9,10 and World Health Organization criteria.7,8 A 12 lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was used to detect left ventricular hypertrophy according to Minnesota coding.11 Although this may overestimate left ventricular mass in people of African origin compared with white people,12 it is the method routinely used in general practice. Peripheral vascular disease was coded from the answers to the Edinburgh questionnaire,13 and renal impairment was defined as serum creatinine concentration >160 μmol/l. No participant had evidence of fundal exudates, haemorrhages, or papilloedema. In line with the guidelines,3 for subsequent analyses on treatment thresholds we excluded 317 participants with previously known diabetes (n=103), left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG (n=103), peripheral vascular disease (n=91), renal impairment (n=2), or other clinical target organ damage (n=18). This left 1069 participants for analysis (404 white people, 342 south Asian, and 323 of African origin).

We compared categorical variables between each ethnic group using age standardisation with the direct method. We used five year age bands with equal numbers in each band. We used analysis of covariance to adjust blood pressure and cholesterol concentration for age and compare between ethnic groups for baseline analysis. The three groups were compared with a global F test. We log transformed high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration and the ratio of total to high density lipoprotein cholesterol before analysis of covariance and report geometric means for ease of reference to absolute values.

We used published equations for predicting the incident risk of CHD, stroke, and combined CVD from the Framingham study to calculate each participant's 10 year risk of a first event, fatal or not fatal (see box).14

Framingham equations for 10 year risk of event

Equation 1:  where βi and xi are defined in table 1.Different values of βi are used for CHD, stroke, and CVD

where βi and xi are defined in table 1.Different values of βi are used for CHD, stroke, and CVD

Equation 2: ς=θ0+μθ1 where θ0 and θ1 are defined in table 2 and μ is defined from equation 1

Equation 3:  μ is defined in equation 1 and ς is defined inequation 2; for other time periods ln(10) can be replaced with the number of years

μ is defined in equation 1 and ς is defined inequation 2; for other time periods ln(10) can be replaced with the number of years

Equation 4: 10 year risk of event =  where u is defined in equation 3

where u is defined in equation 3

The independent variables included in the equation were age, sex, systolic blood pressure, total:high density lipoprotein cholesterol, smoking, and diabetes (American Diabetes Association definition). Blood pressure was considered irrespective of whether or not participants were on antihypertensive treatment.15

We compared risk between each ethnic group by analysis of variance, weighting each observation by the inverse of the number of patients in each age-sex-ethnicity group, thereby adjusting for age and sex, using five year age bands. We estimated the associations between risk of CVD and CHD in different ethnic groups by regression analysis and calculated confidence intervals for the regression coefficients using the bootstrap method. The sensitivity of the estimated risk of CHD to predict the risk of CVD in people with no cardiovascular complications was calculated in each ethnic group and for different thresholds of risk of CHD.16 The population attributable risk for high blood pressure was estimated by replacing in the Framingham equations all systolic blood pressures >140 mm Hg with 139 mm Hg (that is, we assumed that treatment would result in a systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg). We calculated the average reduction in risk for all participants in each ethnic group.16 This is a conservative estimate of the number of cardiovascular events (per 1000 population per year) that would be prevented if all participants with a systolic blood pressure above target were successfully treated and their blood pressure was reduced to <140 mm Hg because in some patients systolic blood pressure would be reduced to lower than 139 mm Hg. The analysis was carried out using Stata 6.0 and SPSS 10.0.

Results

Table 3 gives details of participants. People of African origin had higher blood pressure and higher concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol compared with the other ethnic groups. Diabetes (using both classifications) was more common among ethnic minority groups, and smoking was more common among white people.

Table 3.

Age adjusted means (95% confidence interval) of variables used in Framingham equation to estimate 10 year risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and combined cardiovascular disease

| Variables

|

White

|

South Asian

|

African origin

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||

| No of men | 215 | 227 | 184 |

| Age (years)* | 50.4 (49.6 to 51.1) | 49.2 (48.4 to 49.9) | 51.6 (50.8 to 52.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 127 (125 to 130) | 131 (128 to 133) | 133 (130 to 136) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 82 (80 to 83) | 86 (84 to 87) | 87 (86 to 89) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 6.2 (6.1 to 6.4) | 5.7 (5.6 to 5.9) | 5.4 (5.3 to 5.6) |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l)† | 1.22 (1.18 to 1.26) | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.09) | 1.30 (1.26 to 1.35) |

| Total:HDL cholesterol† | 5.0 (4.8 to 5.2) | 5.3 (5.1 to 5.5) | 4.1 (3.9 to 4.3) |

| Current smoking (%) | 40 (33 to 46) | 26 (20 to 32) | 18 (12 to 24) |

| Diabetes by WHO (%) | 6 (2 to 9) | 24 (18 to 30) | 16 (10 to 22) |

| Diabetes by ADA (%) | 3 (1 to 5) | 20 (15 to 25) | 16 (10 to 21) |

| Women | |||

| No of women | 260 | 220 | 280 |

| Age (years)* | 49.1 (48.4 to 49.8) | 48.7 (47.9 to 49.4) | 50.2 (49.5 to 50.8) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 124 (121 to 126) | 128 (126 to 130) | 133 (131 to 136) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 77 (76 to 78) | 80 (79 to 81) | 85 (84 to 86) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 6.2 (6.1 to 6.4) | 5.7 (5.6 to 5.8) | 5.7 (5.6 to 5.8) |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l)† | 1.47 (1.42 to 1.52) | 1.28 (1.23 to 1.32) | 1.54 (1.50 to 1.59) |

| Total:HDL cholesterol† | 4.2 (4.0 to 4.3) | 4.4 (4.2 to 4.5) | 3.6 (3.5 to 3.7) |

| Current smoking (%) | 33 (27 to 39) | 3 (1 to 5) | 8 (5 to 12) |

| Diabetes by WHO (%) | 5 (2 to 8) | 18 (13 to 24) | 13 (8 to 17) |

| Diabetes by ADA (%) | 3 (1 to 6) | 12 (8 to 16) | 9 (5 to 12) |

HDL=high density lipoprotein; WHO=World Health Organization; ADA=American Diabetes Association.

Not adjusted.

Geometric means.

The estimated 10 year risk of CHD adjusted for age and sex, varied significantly by ethnic group (table 4). South Asians had the greatest risk of CHD and combined CVD, whereas people of African origin had the lowest. However, people of African origin had the highest risk of stroke.

Table 4.

Age and sex adjusted 10 year risk* of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in each ethnic group as estimated by Framingham equations. Figures are means (95% confidence interval)

| White (n=475)

|

South Asian (n=447)

|

African origin (n=464)

|

P value†

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD‡ | 8.8 (8.2 to 9.5) | 9.2 (8.6 to 9.9) | 7.0 (6.5 to 7.5) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.8) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | 0.036 |

| CVD§ | 11.9 (11.0 to 12.7) | 12.5 (11.6 to 13.4) | 10.5 (9.7 to 11.2) | 0.003 |

Equivalent to incidence rate per 1000 per year.

For heterogeneity.

Includes myocardial infarction, CHD death, angina, and coronary insufficiency.

Includes CHD plus stroke, transient ischaemic attack, congestive cardiac failure, and peripheral vascular disease.

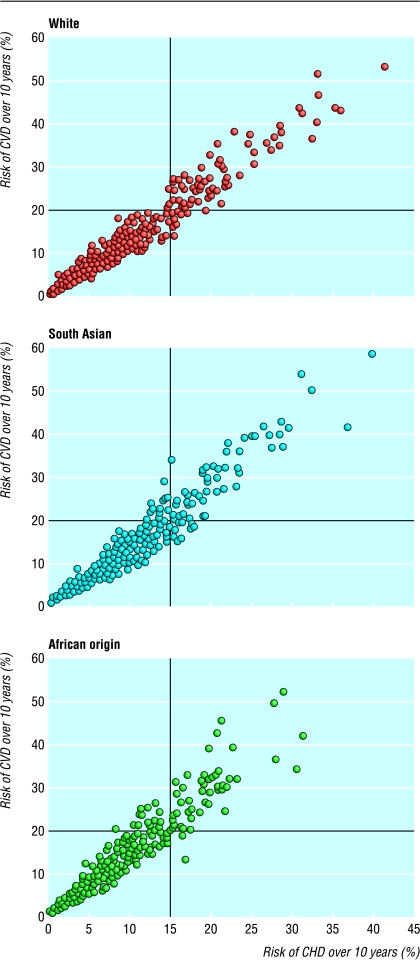

Estimates for risk of CHD and CVD showed a high degree of correlation in each ethnic group (r=0.97, 0.96, 0.96 in white people, south Asians, and people of African origin, respectively). However, the slope of the regression line of risk of CVD against risk of CHD was steeper in people of African origin and south Asians than in white people (fig 1). This indicates that for a given 10 year risk of CHD the estimated risk of combined CVD is higher in people of African and south Asian origin than in white people.

Figure 1.

Association between risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and risk of combined cardiovascular disease (CVD) in white people (n=475), south Asians (n=447), and people of African origin (n=464) with no evidence of ischaemic heart disease or stroke. Slopes of regression lines are 1.30 (1.27 to 1.34), 1.40 (1.35 to 1.45), and 1.48 (1.40 to 1.55) % increase in risk of CVD per % risk of CHD, respectively; P<0.001

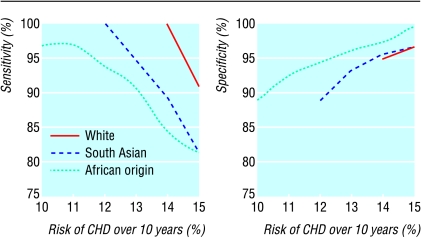

After we excluded those with known diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, periphreal vascular disease, renal impairment, and other organ damage, the probability of having a risk of CVD ⩾20% if the risk of CHD is ⩾15% (that is, sensitivity) was higher in white people (50/55 (91%)) than in south Asians (30/37 (81%)) and people of African origin (26/32 (81%)). However, a risk of CHD ⩾12% would identify 100% of south Asians, and a risk of CHD ⩾10% would identify 97% of people of African origin with a risk of CVD ⩾20% (fig 2). If these new thresholds were used, about 8% of south Asians and 11% of people of African origin with mild hypertension whose risk of CVD was <20% would also receive treatment.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of thresholds for 10 year risk of CHD to identify 10 year risk of CVD ⩾20% in each ethnic group after exclusion of people with known diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, peripheral vascular disease, renal impairment, or other clinical target organ damage

The proportion of participants with blood pressure above the National Service Framework target of 140/85 mm Hg4 was highest among people of African origin (274/464 (59%, 55% to 64%)), intermediate in south Asians (193/447 (43%, 39% to 48%)), and lowest in whites (155/475 (33%, 28% to 37%)), even though the group of people of African origin had the highest proportion of treated individuals (30% v 12% south Asians and 8% white people). The population risks for CHD, stroke, and CVD attributable to systolic blood pressure above target were higher in people of African origin—and to a lesser extent in south Asians—than in white people. For CVD they were 1.11 (0.88 to 1.34), 0.92 (0.68 to 1.15), and 0.67 (0.49 to 0.85) per 1000 population per year, respectively. These differences suggest that adequate treatment of high blood pressure might prevent a proportionally greater number of cardiovascular events in people of African origin and in south Asians than in white people.

Discussion

This is the first study based in general practice to show that the use of risk of CHD in south Asians and people of African origin underestimates their risk of CVD. This implies that we should be using different thresholds—such as, 12% and 10%, respectively—to manage the same overall vascular risk. The associations between risks of CHD and CVD are different between groups so that the use of an estimate of risk of CHD ⩾15% in primary care may result in undertreatment of mild hypertension in south Asians and in people of African origin with a risk of CVD of ⩾20%. Although more people of African origin were receiving treatment, they also had the highest prevalence of blood pressure above target. Therefore, in people of African origin the population risk attributable to blood pressure above target was higher and the potential benefits of adequate management greater.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our participants were from a community population and were being cared for in primary care. Our results are relevant to general practice, where most primary prevention of CHD and management of people with hypertension takes place. All measurements of risk factors were done according to a strict protocol.7,8 Finally the fact that the study was population based avoided the “healthy worker” effect.

The application of risk equations to ethnic groups is based on the assumption that the effect of each risk factor is constant across groups as prospective data on British ethnic minority cohorts are lacking. The differences in estimated risks therefore depend on the level or prevalence of the risk factor. This seems realistic as we have no evidence to suggest that management of risk factors may have differential benefit according to ethnic origin. The study was relatively small and may lack statistical power, particularly where estimates of risk are small, as in stroke. Furthermore, the analysis was restricted to men and women aged 40-59 years, and results may therefore apply only to this age group. We did not take into account family history of premature CHD,2 and we considered blood pressure irrespective of treatment. All these factors will tend to underestimate our calculations of risk. We recorded blood pressure as the average of two measurements taken on a single occasion. National guidelines recommend that blood pressure is considered after repeated measurements.3,5 This may have led to overestimates, thereby overstating risk because in clinical practice drug treatment is not usually started without at least two repeated measurements on different occasions. This would allow for adaptation and lower average blood pressure. However, if this effect was evenly distributed across measurements it should not have biased our results in either direction.

Comparison with other studies

The Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores have recently been validated in American cohorts of different ethnic origin.17 Though they applied to white people and African-Americans, they needed recalibration in other ethnic groups (Japanese, Hispanic, and native Americans). Similarly, southern European populations have a lower rate of CHD and therefore the Framingham equations overestimate the risk and the need for treatment.18 Our risk predictions in white people in south London agree with other estimates in similar UK samples.19–21 However, in south Asians and especially in people of African origin the use of risk of CHD underestimated their risk of CVD. The joint British Societies2 and the BHS Guidelines3 recognise that the current guidelines may underestimate the risk in ethnic minorities. They suggest that the different distribution of risk factors in some communities may require a specific approach tailored to the different profiles of risk factors.2 Our study provides the first quantitative estimate of this to guide clinical practice in the United Kingdom.

Implications

The application of the hypertension guidelines to people with uncomplicated mild hypertension might lead to undertreatment of people of south Asians and African origin, who would not be considered for drug therapy despite high risk of combined CVD. One alternative would be to calculate risk of CVD routinely rather than risk of CHD in these groups and to treat according to risk of CVD, as recently suggested by the European SCORE (systematic coronary risk evaluation) project. However, while some guidelines use the risk of CVD,22 most calculators of risk and charts currently in use in primary care in the United Kingdom give risk of CHD. If general practitioners continue to estimate CHD risk, then lower thresholds (for example, 10% in people of African origin and 12% in south Asians rather than 15%) may be more appropriate to guide management. This would considerably increase the likelihood of being treated and would include most of those with a risk of CVD ⩾20%. A reduction of the threshold of risk of CHD would also lead to a small increase in the number of people with a risk of CVD <20% who would be offered antihypertensive drugs. However, large intervention trials of antihypertensive treatment suggest this is safe, and any reduction in mildly raised blood pressure towards target levels is likely to be associated with reduced morbidity even in this low risk group.23

What is known on this topic

The Framingham equations predict risk of CHD and CVD with reasonable accuracy in white people

These equations have not been validated in the United Kingdom in ethnic minorities

Compared with white people, those of African origin have less CHD but more hypertension, diabetes, strokes, and renal failure; and south Asians have more CHD, hypertension, diabetes, and central obesity

What this study adds

Current CHD risk thresholds underestimate the risk of CVD in people of south Asian and African origin

Use of a 10 year risk of CHD ⩾15% to decide how to manage people with mild uncomplicated hypertension would identify for treatment 91% of white people with a 10 year risk of combined CVD ⩾20% but only 81% of south Asians and people of African origin

If general practitioners used a lower threshold for risk of CHD (for example, 12% and 10%) in south Asian and African people with mild hypertension, they would have a higher probability of identifying and treating those with a risk of CVD ⩾20%

Risk of CVD would be an even better measurement

Detection, management, and control of hypertension in the United Kingdom is currently inadequate,7,24 despite trends in improvement.25 Our study suggests that the ethnic group with the greatest need (people of African origin with higher prevalence of hypertension, greater likelihood of treatment, but worse blood pressure control) may continue to be undertreated because risk of CHD is not an accurate reflection of their risk of combined CVD. This is likely to widen inequalities in management of hypertension and prevention of cardiovascular disease. It may also contribute to an ineffective and inadequate implementation of the National Service Framework for CHD in primary care, particularly in inner cities, where the representation of ethnic minority groups may be high. In contrast better blood pressure control in all groups would lead to a greater proportional reduction in cardiovascular risk in people of south Asian and African origin.

Table 1.

Coefficients for independent variables in Framingham equations

|

i

|

xi

|

Coefficients βi

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD

|

Stroke

|

CVD

|

||

| 1 | Female=1, male=0 | 28.4441 | 0.2019 | −1.2146 |

| 2 | Ln age (years) | −1.4792 | −2.3741 | −1.8443 |

| 3 | (Ln age (years))2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | Ln (age) if female, 0 if male | −14.4588 | 0 | 0.3668 |

| 5 | (Ln age)2 if female, 0 if male | 1.8515 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Ln systolic blood pressure | −0.9119 | −2.4643 | −1.4032 |

| 7 | Current smoker=1, 0 otherwise | −0.2767 | −0.3914 | −0.3899 |

| 8 | Ln (total cholesterol)/(HDL) | −0.7181 | −0.0229 | −0.5390 |

| 9 | Diabetic=1, non-diabetic=0 | −0.1759 | −0.3087 | −0.3036 |

| 10 | Female and diabetic=1, 0 otherwise | −0.1999 | −0.2627 | −0.1697 |

CHD=coronary heart disease, CVD=cardiovascular disease, HDL=high density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Table 2.

Other constants used in equations

| CHD

|

Stroke

|

Coefficients for CVD

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| θ0 | 0.9145 | −0.4312 | 0.6536 |

| θ1 | −0.2784 | 0 | −0.2402 |

| β0 | 15.5305 | 26.5116 | 18.8144 |

Acknowledgments

We thank general practitioners in Wandsworth for allowing us to approach people on their lists and the people who took part in the study. A list of the Wandsworth Heart and Stroke Study Group is given elsewhere.8 We thank Derek Cook for his useful comments to the manuscript. FPC is a member of the St George's Cardiovascular Research Group.

Footnotes

Funding: Former Wandsworth Health Authority, South Thames Regional Health Authority, NHS research and development directorate, British Heart Foundation, British Diabetic Association, and Stroke Association.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Jackson R. Guidelines on preventing cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. BMJ. 2000;320:659–660. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7236.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood D, Durrington P, Poulter NR, McInnes GT, Rees A, Wray R. Joint British recommendations on prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Heart. 1998;80(suppl 2):1–29S. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsay LE, Williams B, Johnston GD, MacGregor G, Poston L, Potter J, et al. Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the third working party of the British Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13:569–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. National service framework for coronary heart disease. London: Stationery Office; 2000. pp. 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsay LE, Williams B, Johnston GD, MacGregor GA, Poston L, Potter JF, et al. British Hypertension Society guidelines for hypertension management 1999: summary. BMJ. 1999;319:630–635. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cappuccio FP. Ethnicity and cardiovascular risk: variations in people of African ancestry and South Asian origin. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11:571–576. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cappuccio FP, Cook DG, Atkinson RW, Strazzullo P. Prevalence, detection, and management of cardiovascular risk factors in different ethnic groups in south London. Heart. 1997;78:555–563. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.6.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cappuccio FP, Cook DG, Atkinson RW, Wicks PD. The Wandsworth heart and stroke study. A population-based survey of cardiovascular risk factors in different ethnic groups. Methods and baseline findings. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 1998;8:371–385. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris T, Cook DG, Cappuccio FP. New diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus. Subjects with impaired glucose tolerance but normal fasting values will not be identified. BMJ. 1999;318:531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris TJ, Cook DG, Wicks PD, Cappuccio FP. Impact of the new American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria for diabetes and impaired fasting glucose on subjects from three different ethnic groups living in the UK. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2000;10:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose GA, Blackburn H, Gillum RF, Prineas RJ. Cardiovascular survey methods. Geneva: WHO; 1982. pp. 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman JN, Mayet J, Chang CL, Foale RA, Thom SAMcG, Poulter NR. Ethnic differences in the identification of left ventricular hypertrophy in the hypertensive patient. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:437–442. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leng GC, Fowkes FGR. The Edinburgh claudications questionnaire: an improved version of the WHO/Rose questionnaire for use in epidemiological surveys. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1101–1109. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90150-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PWF, Kannel WB. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J. 1991;121:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90861-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du X, Cruickshank JK, McNamee R, Saraee M, Sourbutts J, Summer A, et al. Case-control study of stroke and the quality of hypertension control in north west England. BMJ. 1997;314:272–276. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7076.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in medicine. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1987. pp. 1–383. [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Grundy S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores. Results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286:180–187. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menotti A, Lanti M, Puddu PE, Kromhout D. Coronary heart disease incidence in northern and southern European populations: a reanalysis of the seven countries study for a European coronary risk chart. Heart. 2000;84:238–244. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.3.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haq IU, Ramsay LE, Yeo WW, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ. Is the Framingham risk function valid for northern European populations? A comparison of methods for estimating absolute coronary risk in high risk men. Heart. 1999;81:40–46. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE, Haq IU, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR. Is coronary risk an accurate surrogate for cardiovascular risk for treatment decisions in mild hypertension? A population validation. J Hypertens. 2001;19:691–696. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE, Haq IU, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Rowland-Yeo K, et al. Coronary and cardiovascular risk estimation for primary prevention: validation of a new Sheffield table in the 1995 Scottish health survey population. BMJ. 2000;320:671–676. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7236.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson R. Updated New Zealand cardiovascular disease risk-benefit prediction guide. BMJ. 2000;320:709–710. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7236.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, Hebert P, Fieback NH, Eberlein KA, et al. Blood pressure, stroke and coronary heart disease. II. Short term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335:827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Primatesta P, Bost L, Poulter NR. Blood pressure levels and hypertension status among ethnic groups in England. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:143–148. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Primatesta P, Brookes M, Poulter NR. Improved hypertension management and control. Results from the Health Survey for England 1998. Hypertension. 2001;38:827–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]