Abstract

WHITE COLLAR-1 (WC-1) is the limiting component of the White Collar Complex (WCC) controlling expression of the Neurospora circadian clock protein Frequency (FRQ). Accumulation of WC-1 is supported by FRQ on a post-transcriptional level. Here, we show that transcription of wc-1 is organized in a complex way. Three promoters drive transcription of wc-1. Pdist is dependent on WCC. Pprox is independent of WCC in darkness, but inducible by light in a WCC-dependent manner. A third promoter, Pint, is located in the wc-1 open reading frame and promotes expression of an amino-terminally truncated WC-1 isoform of unknown function. Expression of wc-1 by Pdist or Pprox alone, or by a heterologous promoter, affects the entrained phase of circadian conidiation and the response of Neurospora to light. Our results indicate that transcriptional regulation of wc-1 is required to modulate the circadian phase of clock output.

Keywords: circadian rhythms, White Collar Complex, FRQ, feedback regulation, Neurospora

Introduction

Most organisms have evolved circadian clocks to adapt their physiology to the daily changes in the environment. On the molecular level, circadian clocks are composed of positive and negative elements that form interlocked transcriptional and translational feedback loops (Stanewsky, 2003; Dunlap & Loros, 2004; Gachon et al, 2004). In Neurospora, the White Collar Complex (WCC), composed of WHITE COLLAR (WC)-1 and WC-2, activates transcription of the clock gene frequency (frq; Linden & Macino, 1997; Froehlich et al, 2002). Two isoforms of FREQUENCY (FRQ) protein are expressed, which are crucial for temperature compensation and resetting of the clock (Liu et al, 1997; Diernfellner et al, 2005). FRQ promotes phosphorylation of WCC, leading to its inactivation (Schafmeier et al, 2005), and thus to negative feedback on frq transcription (Froehlich et al, 2003; Dunlap & Loros, 2004). FRQ is then degraded through a phosphorylation- and proteasome-dependent pathway (Görl et al, 2001; He et al, 2003). FRQ also supports expression of WC-1 and WC-2 (Lee et al, 2000; Cheng et al, 2001), and WC-1 represses wc-2 transcription (Cheng et al, 2003). These interconnected positive and negative feedback loops lead to rhythmic expression of FRQ and thus to rhythmic activity of WCC. WCC serves as a blue-light receptor required for resetting and entrainment of the clock (Linden & Macino, 1997; Cheng et al, 2003; Lee et al, 2003). FRQ and WCC regulate circadian expression of clock-controlled genes and thereby determine rhythmicity of physiological processes.

Activation of the frq promoter by WCC has been characterized in detail (Froehlich et al, 2002, 2003). Two WCC-binding elements within the promoter are necessary to maximally induce frq transcription in response to light. The distal element (C-box) is necessary and sufficient to promote rhythmic frq expression in darkness.

Here, we characterized transcription of wc-1. We identified three distinct promoters. Pdist and Pprox give rise to transcripts with long 5′-untranslated regions (5′-UTRs). Pdist is activated by WCC, whereas Pprox is independent of WCC in darkness but transiently induced by light in a WCC-dependent manner. The third promoter, Pint, is located in the wc-1 open reading frame (ORF). Although the physiological relevance of Pint is not clear, it has the potential to drive the expression of an amino-terminally truncated, partially functional WC-1 isoform. Our results indicate that WC-1 positively regulates its own expression and thus forms another feedback loop, stabilizing the Neurospora clockwork. Complex transcriptional regulation of wc-1 seems to be required to adjust the circadian phase of conidiation.

Results

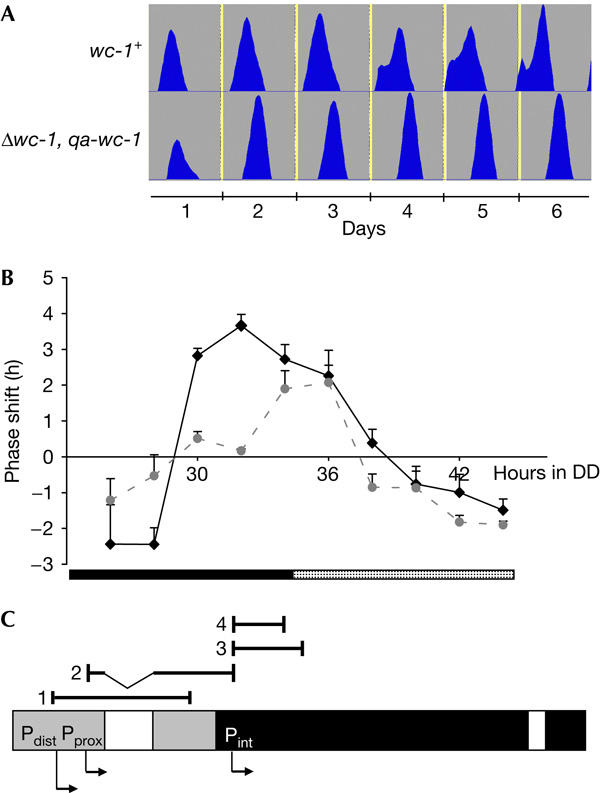

The wc-1 gene contains three promoters

Expression levels of wc-1 RNA do not show circadian rhythmicity (Lee et al, 2000; Merrow et al, 2001). In accordance, expression of WC-1 under the control of the inducible quinic acid-2 (qa-2) promoter was shown to restore free-running rhythmicity in a wc-1 null strain (Cheng et al, 2001). WC-1 levels in a Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 are similar to those in a bd A control strain (supplementary Fig 1 online), henceforth referred to as wc-1+. However, we observed that the phase of circadian conidiation of Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 was delayed by ∼30 min compared with wc-1+ (Table 1). This difference was even more pronounced when strains were entrained to light:dark (LD) cycles (Fig 1A; Table 1). In 12 h:12 h, 6 h:18 h and 1 h:23 h LD cycles, the phase of Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 was delayed by 2 h 40 min, 3 h 6 min and 4 h 12 min, respectively. Thus, expression of WC-1 from a heterologous promoter affects the response of Neurospora to light. We therefore investigated resetting of the phase of the circadian clock by 20 min light pulses received at different time points throughout a circadian period (Fig 1B). In Neurospora, conidiation is initiated in the second half of the night. Light signals received before the initiation of conidiation delay the phase and suppress formation of conidia, whereas light signals received close to and after the onset advance the phase. Thus, the largest difference in phase response is observed between light pulses given shortly before and after the initiation of conidiation. As expected, light pulses towards the end of the subjective night and during the early subjective morning evoked advances of the phase of conidiation in wc-1+, whereas light pulses towards the end of the subjective day and during the first half of the night delayed the phase (Fig 1B). The maximal differences between phase delays and advances were about 8 h in the quinic acid medium used (Fig 1B). Even larger phase shifts were observed under different growth conditions (Heintzen et al, 2001). The phase response of Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 to light pulses during the subjective day was similar to that of wc-1+. However, Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 was less responsive to light signals during the subjective night. In particular, the maximal differences in phase shifts were less than 3 h. The observations suggest that transcriptional control of wc-1 is crucial for resetting of the circadian clock by light pulses received during the subjective night. Thus, the wc-1 gene might be regulated in a more complex manner than anticipated hitherto.

Table 1.

Altered entrainment of conidiation rhythm in Δwc-1, qa-wc-1

| Period (h; mean±s.e.m.) | Peak of conidiation (h; mean±s.e.m.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DD | wc-1+ | 21.83±0.17 | 22.28±0.15 (CT) |

| |

Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 |

21.44±0.26 |

22.81±0.32 (CT) |

| LD (12:12) | wc-1+ | 24.3±0.32 | 22.81±0.31 (ZT) |

| |

Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 |

24.06±0.024 |

1.50±0.59 (ZT) |

| LD (6:18) | wc-1+ | 24.01±0.32 | 18.7±0.34 (ZT) |

| |

Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 |

24.45±0.13 |

21.84±0.5 (ZT) |

| LD (1:23) | wc-1+ | 23.62±0.005 | 8.32±0.20 (ZT) |

| Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 | 24.07±0.09 | 12.70±0.27 (ZT) |

Race tubes were inoculated with the indicated strains and after incubation in constant light for 2 days transferred to DD or LD cycles at 25°C as indicated (n=5–14). CT, circadian time; DD, constant darkness; LD, light:dark; ZT, zeitgeber time.

Figure 1.

Complex control of wc-1 transcription. (A) Entrainment of circadian conidiation depends on the wc-1 promoter. Race tubes, inoculated with the indicated strains, were exposed to 1 h:23 h light:dark cycles at 25°C. Averaged conidial densities (n=3) were plotted versus time. (B) Resetting of the clock by light is altered in the Δwc-1, qa-wc-1 (dotted grey line) strain compared with wc-1+ (black line). Race tubes were exposed to 20 min light pulses at the indicated time in constant darkness (DD). The phase shift of conidial bands (compared with control strains kept in DD) was blotted versus time when the light pulse was given. Black and dotted bars at the bottom indicate subjective night and day, respectively. (C) The transcription of wc-1 is initiated at various sites. The wc-1 gene is schematically outlined. The positions of four amplicons generated by RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of complementary DNA ends are indicated above. The putative promoters Pdist, Pprox and Pint are indicated by arrows.

Therefore, we mapped the 5′ ends of wc-1 transcripts of light-grown wild type (wt) by RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of complementary DNA ends (5′RLM-RACE). We identified two putative transcription starts at positions –1222 and −924 with respect to the wc-1 ORF and one at position +175, suggesting a promoter within the wc-1 ORF (Fig 1C). Sequence analysis and diagnostic PCR (not shown) showed a 420 nt intron between positions −866 and −445.

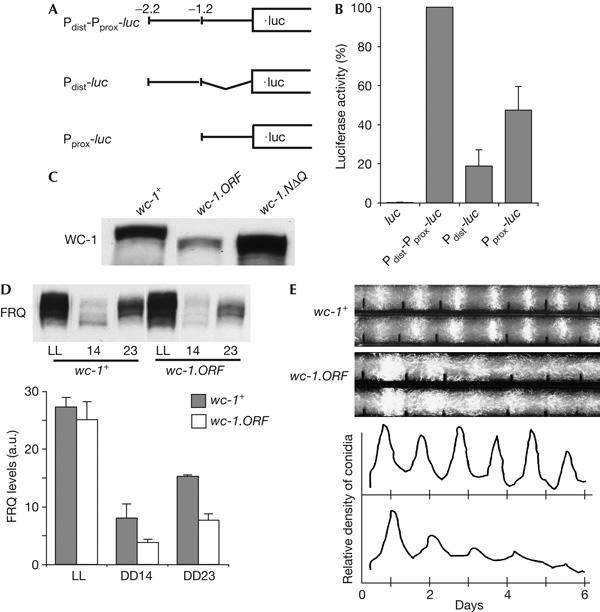

We tested the promoter activity of different wc-1 gene segments using firefly luciferase (luc) as reporter (Fig 2A). The strains Pdist-Pprox-luc, Pdist-luc and Pprox-luc contain in front of the luc gene fragments corresponding to −2223 to −1, −2223 to −1212 and −1179 to −1 of the wc-1 gene, respectively. The reporter strains were grown in constant light (LL). Total protein extracts were prepared and luc activity was measured. Luc activity in Pdist-Pprox-luc extracts was about 200 times higher than that in extracts of a control strain transformed with a promoterless luc gene (Fig 2B). Luc activity of Pdist-luc and Pprox-luc extracts was 40- and 100-fold higher than control levels, respectively. The data indicate that the wc-1 gene contains two promoters, Pdist and Pprox, initiating transcripts 1,222 and 924 bp upstream of the wc-1 ORF, respectively. About half of the transcriptional activity of wc-1 can be attributed to Pprox, suggesting that Pdist is of equal strength. However, Pdist-luc activity was only 20% of the activity of Pdist-Pprox-luc. As the 5′UTRs of the two constructs are different, luc activity may not accurately reflect the strength of Pprox in the wc-1 gene.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the promoter activity of different wc-1 gene segments. (A) Schematic outline of luciferase (luc) reporter constructs. (B) Different wc-1 gene segments exert promoter activity. wc-1+,his3 was transformed with the indicated constructs and luc activity was measured in total cell extracts of light-grown cells. Enzyme activity measured in extracts of wc-1+, Pdist-Pprox-luc was set to 100%. Data are means±s.e.m. of five to eight experiments. (C) The wc-1.ORF strain expresses an amino-terminally truncated version of WC-1. wc-1+ and the strains wc-1.ORF and Δwc-1, qa-wc-1.NΔQ were grown in constant light (LL). Expression of WC-1.NΔQ (amino acids 67–1,167) was induced with quinic acid. Total cell extracts were analysed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with anti-WC-1 antibody. (D) Frequency (FRQ) levels in wc-1.ORF are high in LL but reduced in constant darkness (DD). A representative western blot analysis of total cell extract and quantification by densitometry (n=3) is shown. (E) The conidiation rhythm of wc-1.ORF is dampened. Two representative race tubes and the averaged conidial densities are shown.

To investigate the physiological relevance of the 5′RLM-RACE products starting within the wc-1 coding region, the ORF was inserted without additional regulatory sequences into the his-3 locus of Δwc-1, resulting in the strain wc-1.ORF. A shorter version of WC-1 was detected with an antibody directed against the carboxyl terminus of WC-1, indicating that an N-terminally truncated version of WC-1 was expressed in this strain (Fig 2C). The electrophoretic mobility of the truncated WC-1 species was similar to that of WC-1.NΔQ, a recombinant version, in which the N-terminal polyglutamine (poly(Q)) stretch of WC-1 was deleted and which starts at methionine 67. We estimated that the WC-1.NΔQ level directed by the ORF reached more than 25% of the WC-1 level in wt. This indicates that the wc-1 ORF contains a promoter that drives expression of a truncated WC-1 protein lacking the N-terminal poly(Q) stretch. Despite the presence of Pint RNA, the truncated WC-1 species seems to be expressed only at a low level in wt, but accumulates to significant amounts when expression of full-size WC-1 is compromised. The physiological role of the truncated WC-1 is not clear. In LL, the wc-1.ORF strain expressed wt levels of FRQ, whereas FRQ levels were reduced at DD14 (14 h after LD transfer) and at DD23 (23 h after LD transfer; Fig 2D). When analysed on race tubes, wc-1.ORF was initially rhythmic in constant darkness (DD), but the rhythm dampened after 3 days (Fig 2E).

Taken together, the above data indicate that wc-1 transcription is controlled by several promoter elements allowing production of different messenger RNA and also different protein species.

WC-1 controlled activity of the wc-1 promoter segments

FRQ regulates WC-1 expression, at least in part, on a post-transcriptional level (Lee et al, 2000; Cheng et al, 2001). Conversely, the level of wc-1 RNA is transiently induced by light and then adapts in LL to levels similar to those in DD (Ballario et al, 1996; Merrow et al, 2001; Lee et al, 2003). This suggests that wc-1, like other light-induced genes, is controlled by WC-1 and VIVID, the blue-light photoreceptors of Neurospora (Dunlap & Loros, 2004).

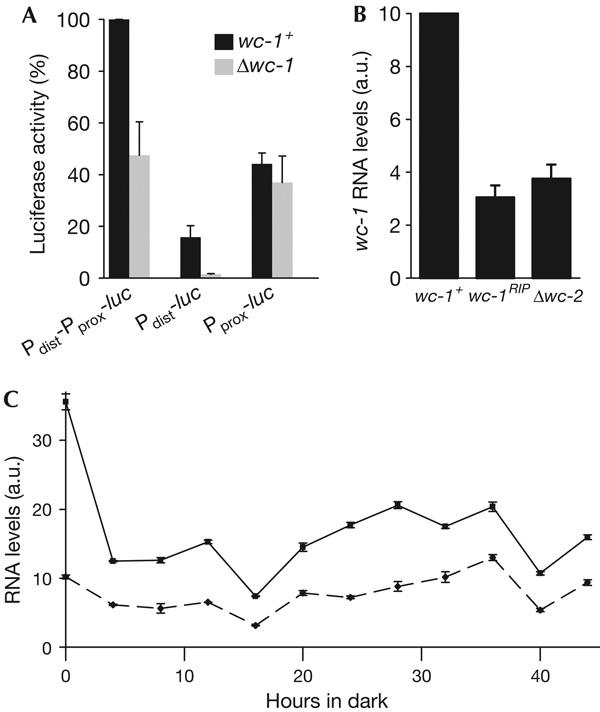

To investigate whether expression of wc-1 in darkness is dependent on WC-1, we transformed a Δwc-1 strain with Pdist-Pprox-luc. luc activity was about 50% lower than that in wt transformed with Pdist-Pprox-luc (Fig 3A), suggesting a role of WC-1 in the regulation of its own transcription even in DD. In accordance, we found that wc-1 transcript levels were reduced in Δwc-2 and wc-1RIP strains, which lack functional WCC (Fig 3B).

Figure 3.

Expression of wc-1 in constant darkness is dependent on the White Collar Complex. (A) WC-1 regulates distinct promoter segments of wc-1 in constant darkness (DD). Indicated constructs (see Fig 2) were integrated into the his3 locus of wc-1+ and of Δwc-1. Luciferase (luc) activity was measured in total cell extracts prepared from cultures collected at DD23. 100%, enzyme activity measured in wc-1+, Pdist-Pprox-luc. Data are means±s.e.m. of four experiments. (B) wc-1 expression is reduced in the White Collar Complex-deficient strains wc-1RIP and Δwc-2. Cells were collected at DD24. wc-1 RNA was analysed by quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR). Data are means±s.e.m. of three experiments, each carried out in duplicate. (C) Activity of Pdist and Pprox in constant light (LL) and DD. wc-1+ was grown in LL (0) and then transferred to DD. Samples were collected at the indicated time points and total wc-1 RNA (solid black line) and Pdist-specific RNA (dotted grey line) were measured by RT-PCR (supplementary information online).

To analyse which promoter is controlled by WC-1, Δwc-1 was transformed with Pdist-luc and Pprox-luc constructs. Pdist-luc activity in DD was significantly lower in Δwc-1 than that in transformed wc-1+, whereas Pprox-luc showed comparable activities in both strains (Fig 3A). This indicates that Pdist transcription in DD is supported by WC-1, whereas Pprox transcription is independent of WC-1.

Using specific real-time PCR (RT-PCR) probes, we measured total wc-1 RNA and transcripts of Pdist in LL and DD during the course of two circadian cycles (Fig 3C). Transcript levels were variable in DD but did not show apparent circadian rhythmicity. The average level of Pdist-specific RNA in DD was similar to the level in LL, whereas total wc-1 RNA levels were about twofold higher in LL than those in DD.

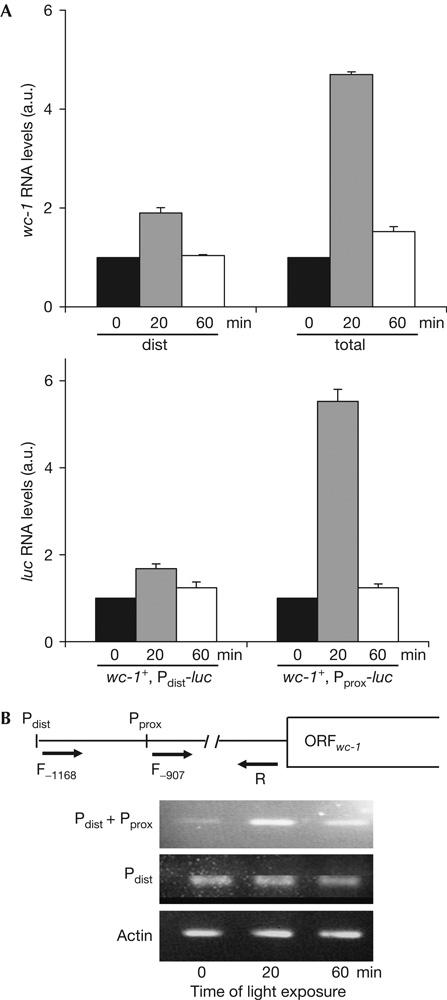

To address whether the two promoters are transiently induced by light, we measured wc-1 RNA in wc-1+ and luc RNA in transformed wc-1+ reporter strains. Cultures were grown in DD and then exposed to light. wc-1 and luc RNA levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig 4A). Pdist-specific wc-1 RNA was only moderately induced by light. Following dark-to-light transfer, total wc-1 RNA level increased by about fivefold in 20 min and adapted in 60 min to levels about twofold higher than those in DD (Fig 4A, upper panel). As Pint is not light responsive (not shown), the data indicate that Pprox is induced by light. In support of this, we found that Pprox-luc transcription was induced by light, whereas Pdist-luc transcription was essentially unaffected by light (Fig 4A, lower panel). This suggests that Pprox contains a light-responsive element (LRE). To confirm these results, we compared the amount of Pdist- and Pprox-dependent transcripts by semiquantitative PCR using cDNA of light-induced and dark-grown wt strains (Fig 4B). Two forward primers were used to detect Pdist transcripts alone or Pdist+Pprox transcripts together. Total wc-1 RNA, driven by Pdist+Pprox, was transiently induced by light, whereas Pdist-specific transcripts were not induced by light, indicating that Pprox responds to light.

Figure 4.

Localization of the light-inducible promoter element of the wc-1 gene. (A) Pprox contains a light-responsive element (LRE). wc-1+ (upper panel), wc-1+, Pdist-luc and wc-1+, Pprox-luc (lower panel) were incubated in constant darkness for 24 h and then transferred to light for the indicated periods. Upper panel: total wc-1 RNA and Pdist-specific RNA were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Lower panel: luc RNA expressed by the indicated strains was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. RNA levels before light induction were set equal to unity. (B) Pprox transcripts are light inducible. Upper panel: schematic outline showing forward (F) and reverse (R) primers with respect to Pdist and Pprox. Numbers (−907 and −1168) indicate the distance in base pairs from the AUG. Lower panel: semiquantitative PCR (23 cycles) was carried out on complementary DNAs prepared from wc-1+ after light exposure for the indicated time periods. Actin was used as a control.

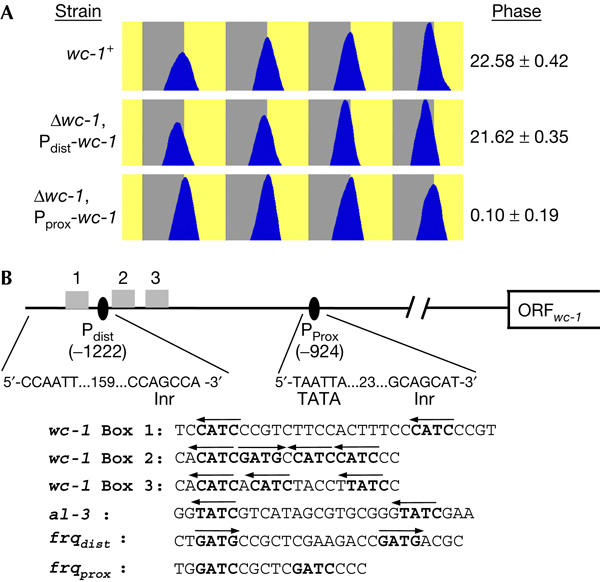

To investigate how expression of WC-1 under the control of Pprox or Pdist alone would affect free-running rhythmicity and entrained phase of conidiation, we constructed the strains Δwc-1, Pprox-wc-1 and Δwc-1, Pdist-wc-1. Expression levels of WC-1 were slightly reduced in these strains (supplementary Fig 2 online). Both strains were rhythmic in DD (supplementary table online). The free-running period of Δwc-1, Pprox-wc-1 was 24.8 h and the peak of conidiation (phase) was at circadian time (CT23.5). The free-running period of Δwc-1, Pdist-wc-1 was 22.4 h and the phase of conidiation was at CT21.1. When exposed to 12 h:12 h LD cycles, the phase of conidiation of Δwc-1, Pdist-wc-1 was advanced by ∼1 h and the phase of Δwc-1, Pprox-wc-1 was delayed by ∼1.5 h, compared with the phase of wc-1+ (Fig 5A).

Figure 5.

Complex transcriptional control of wc-1. (A) Expression of wc-1 by Pdist and Pprox is required for entrainment. Race tubes were inoculated with the indicated strains and exposed to 12 h:12 h light:dark cycles. Conidial densities were plotted versus time. Phases of conidiation peaks were calculated as zeitgeber time (h; mean±s.e.m.). (B) Regulation of Pdist and Pprox by the WCC. Upper panel: schematic outline of the wc-1 gene. Pdist and Pprox are indicated. A putative CAAT box, TATA box and initiator sequences are shown. The grey boxes (Box 1–3) indicate putative GATN-type binding sites for WCC. Lower panel: sequence comparison of wc-1 (Box 1–3) and the light-responsive elements of frq (Froehlich et al, 2002) and al-3 (Carattoli et al, 1994). The arrows indicate the orientation of GATN elements.

Discussion

The Neurospora blue-light photoreceptor WC-1 assembles with its partner WC-2, forming the WCC, which regulates expression of the circadian oscillator protein FRQ and several light-induced and clock-controlled genes (Roenneberg & Merrow, 2001; Dunlap & Loros, 2004). As WC-2 is present in excess, levels of WC-1 determine the concentration of WCC. WC-1 and WC-2 are GATA-type transcription factors (Ballario et al, 1996; Linden & Macino, 1997), and WCC binds to direct GATN repeats with variable spacing. In the al-3 promoter, WCC binds to GATA repeats (lower strand) spaced by 15 bp (Linden & Macino, 1997), and in the frq promoter, it binds to a distal and a proximal LRE that contain direct GATG repeats (upper strand) spaced by 13 bp and GATC repeats spaced by 5 bp, respectively (Froehlich et al, 2002; Fig 5).

In this study, we addressed the transcriptional regulation of wc-1. We identified three transcription initiation sites in the wc-1 gene. Two sites are located 1,222 and 924 bp upstream of the wc-1 ORF and the third site is located within the wc-1 ORF (Fig 5). Luc reporter assays and analysis of WC-1 expression driven by different wc-1 gene segments confirmed that the sequences located upstream of the identified transcriptional start sites exert promoter activity in vivo. All three transcripts were expressed under dark and light conditions.

Pdist transcription is strongly dependent on WC-1 in LL and DD, but is not induced by light. A putative CCAAT box is located 159 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site of Pdist, but no apparent TATA box is present. A potential GATA-type binding site for WCC, Box 1, is located 49 bp upstream of the mRNA start (Fig 5). The spacing of the two CATC repeats comprises 16 bp. The same repeats with a similar spacing (13 bp) are present in opposite orientation in the distal LRE of the frq promoter (Froehlich et al, 2002). Although it remains to be investigated whether these elements are WCC-binding sites, our data show that WC-1 supports its own expression directly or indirectly by Pdist.

The second transcription initiation site, Pprox, is located only 298 bp downstream of Pdist. No additional CCAAT box is present in Pprox, but the sequence motif TAATTA, 27 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site, could function as a TATA box. Two putative WCC-binding sites, Box 2 and Box 3, are located 261 and 184 bp upstream of the initiation site of Pprox. As Box 2 is located close to the transcription initiation site of Pdist, the two promoters may not function completely independent of each other. Transcription directed by Pprox is independent of WC-1 in DD but is induced when Neurospora is transferred to light. Light induction and adaptation of wc-1 are dependent on WCC and the second Neurospora blue-light photoreceptor Vivid, respectively (Ballario et al, 1996; Schwerdtfeger & Linden, 2003).

The third promoter, Pint, directs transcription of a message that starts 175 bp within the wc-1 ORF and encodes an N-terminally truncated version of WC-1. No consensus promoter elements are found in the 5′ region of the RNA start. Yet, in the absence of Pdist and Pprox, Pint-specific transcription leads to accumulation of significant levels of the truncated WC-1 version. In the presence of Pdist and Pprox, Pint-specific transcripts are detected, but the truncated WC-1 version does not accumulate in high amounts, suggesting that it has a reduced stability or is less competent in WCC assembly. The truncated version of WC-1 is at least partially functional. wc-1.ORF shows a dampened rhythmicity on race tubes in DD and synthesis of FRQ is light inducible.

Why is wc-1 transcribed in an apparently complex way using three differentially regulated promoters? The physiological role of Pint is obscure. Pprox seems to supply basal levels of wc-1 RNA, and thus of WC-1, independent of WCC levels. Pprox and Pdist are both required for adjusting the entrained phase of conidiation. Strains expressing WC-1 from Pprox or from Pdist alone are rhythmic, but the entrained phase of conidiation is delayed or advanced, respectively. Pdist is directly or indirectly activated by WCC. The physiological significance of this positive feedback of WCC on Pdist might be to balance WCC and FRQ levels. It has been shown that such balance is required to ensure robust circadian rhythmicity (Cheng et al, 2001). Thus, when high levels of FRQ accumulate, which efficiently repress frq, high levels of WCC seem to be required to overcome the negative feedback and induce a new cycle of frq transcription. As FRQ supports accumulation of WCC on a post-transcriptional level, WCC is an indicator of FRQ abundance. Thus, a positive feedback regulation of Pdist may allow accumulation WCC according to FRQ levels.

Methods

Strains and growth conditions. All strains carried the bd mutation (Loros et al, 1986). Plasmid constructs were inserted into the his-3 locus and strains were grown as described in the supplementary information online.

Protein analysis and luciferase activity assay. Extraction of Neurospora protein and western blotting were carried out as described (Görl et al, 2001). Conditions of luc assay are given in the supplementary information online.

RNA analysis. RNA was prepared and analysed by quantitative RT-PCR or by semiquantitative PCR (Görl et al, 2001). 5′RLM-RACE was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA).

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/7400595-s1.pdf).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank J.J. Loros and J.C. Dunlap for Δwc-2, G. Macino for qa-2pWC-1 and D. Bell-Pedersen for pLUC6dBs. We thank J. Payk and I. Wörz for excellent assistance. This work was supported by grants from Deutsche-Forschungsgemeinschaft (BR 1375-1 and SFB 638) and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. K.K. was supported by Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung and the Hungarian Scholarship Board.

References

- Ballario P, Vittorioso P, Magrelli A, Talora C, Cabibbo A, Macino G (1996) White collar-1, a central regulator of blue light responses in Neurospora, is a zinc finger protein. EMBO J 15: 1650–1657 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A, Cogoni C, Morelli G, Macino G (1994) Molecular characterization of upstream regulatory sequences controlling the photoinduced expression of the albino-3 gene of Neurospora crassa. Mol Microbiol 13: 787–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P, Yang Y, Liu Y (2001) Interlocked feedback loops contribute to the robustness of the Neurospora circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 7408–7413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P, Yang Y, Wang L, He Q, Liu Y (2003) WHITE COLLAR-1, a multifunctional Neurospora protein involved in the circadian feedback loops, light sensing, and transcription repression of wc-2. J Biol Chem 278: 3801–3808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diernfellner AC, Schafmeier T, Merrow MW, Brunner M (2005) Molecular mechanism of temperature sensing by the circadian clock of Neurospora crassa. Genes Dev 19: 1968–1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap JC, Loros JJ (2004) The neurospora circadian system. J Biol Rhythms 19: 414–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich AC, Liu Y, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC (2002) White Collar-1, a circadian blue light photoreceptor, binding to the frequency promoter. Science 297: 815–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich AC, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC (2003) Rhythmic binding of a WHITE COLLAR-containing complex to the frequency promoter is inhibited by FREQUENCY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5914–5919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachon F, Nagoshi E, Brown SA, Ripperger J, Schibler U (2004) The mammalian circadian timing system: from gene expression to physiology. Chromosoma 113: 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görl M, Merrow M, Huttner B, Johnson J, Roenneberg T, Brunner M (2001) A PEST-like element in FREQUENCY determines the length of the circadian period in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J 20: 7074–7084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Cheng P, Yang Y, He Q, Yu H, Liu Y (2003) FWD1-mediated degradation of FREQUENCY in Neurospora establishes a conserved mechanism for circadian clock regulation. EMBO J 22: 4421–4430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintzen C, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC (2001) The PAS protein VIVID defines a clock-associated feedback loop that represses light input, modulates gating, and regulates clock resetting. Cell 104: 453–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Dunlap JC, Loros JJ (2003) Roles for WHITE COLLAR-1 in circadian and general photoperception in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 163: 103–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC (2000) Interconnected feedback loops in the Neurospora circadian system. Science 289: 107–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden H, Macino G (1997) White collar-2, a partner in blue-light signal transduction, controlling expression of light-regulated genes in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J 16: 98–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Garceau NY, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC (1997) Thermally regulated translational control of FRQ mediates aspects of temperature responses in the Neurospora circadian clock. Cell 89: 477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loros JJ, Richman A, Feldman JF (1986) A recessive circadian mutation at the frq locus of Neurospora crassa. Genetics 114: 1095–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrow M, Franchi L, Dragovic Z, Görl M, Johnson J, Brunner M, Macino G, Roenneberg T (2001) Circadian regulation of the light input pathway in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J 20: 307–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg T, Merrow M (2001) Seasonality and photoperiodism in fungi. J Biol Rhythms 16: 403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafmeier T, Haase A, Káldi K, Scholz J, Fuchs M, Brunner M (2005) Transcriptional feedback of Neurospora circadian clock gene by phosphorylation-dependent inactivation of its transcription factor. Cell 122: 235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger C, Linden H (2003) VIVID is a flavoprotein and serves as a fungal blue light photoreceptor for photoadaptation. EMBO J 22: 4846–4855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanewsky R (2003) Genetic analysis of the circadian system in Drosophila melanogaster and mammals. J Neurobiol 54: 111–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information