Abstract

We have determined the human genome to contain 296 different Src homology-3 (SH3) domains and cloned them into a phage-display vector. This provided a powerful and unbiased system for simultaneous assaying of the complete human SH3 proteome for the strongest binding to target proteins of interest, without the limitations posed by short linear peptide ligands or confounding variables of more indirect methods for protein interaction screening. Studies involving three ligand proteins, human immunodeficiency virus-1 Nef, p21-activated kinase (PAK)2 and ADAM15, showed previously reported as well as novel SH3 partners with nanomolar affinities specific for them. This argues that SH3 domains may have a more dominant role in directing cellular protein interactions than has been assumed. Besides showing potentially important new SH3-directed interactions, these studies also led to the discovery of novel signalling proteins, such as the PAK2-binding adaptor protein POSH2 and the ADAM15-binding sorting nexin family member SNX30.

Keywords: SH3, Nef, PAK2, ADAM15, POSH2, SNX30

Introduction

The Src homology-3 (SH3) domain is the most common of the modular protein interaction domains that control cell behaviour (Macias et al, 2002; Mayer & Saksela, 2004). Because SH3 domains participate in the regulation of cell growth and differentiation, they are involved in pathogenesis of diseases such as cancer, and microbial pathogens, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), also exploit cellular SH3-mediated processes.

SH3 domains are relatively short (∼60 residues) modules, the primary activity of which is to bind to proline-rich peptides. These typically contain a PxxP core-binding motif flanked by a basic residue (RxxPxxP or PxxPxR), but many examples of unconventional SH3 binding sites are also known (Mayer & Saksela, 2004). Further contacts between the SH3 loop regions and ligand residues outside the PxxP motif can greatly enhance specificity and affinity of binding (Mayer & Saksela, 2004).

Human proteome contains hundreds of SH3 domains and SH3 target proteins, creating an enormous number of theoretically possible SH3 interactions. Knowing which ones of these take place and are biologically meaningful would greatly increase our understanding about the signalling networks that regulate normal and pathological cellular behaviour.

Both experimental, such as yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screens, and computational approaches have been used to address this question (Brannetti et al, 2000; Panni et al, 2002; Tong et al, 2002; Landgraf et al, 2004), but these approaches have several limitations. For example, the intensity of the signal indicative of a Y2H interaction can be strongly influenced by yeast clone-specific factors and the dependence on nuclear transport of both of the interacting proteins. On the other hand, strong and selective SH3 binding often involves molecular contacts unique to individual SH3–ligand complexes that are difficult to address by homology modelling and computational prediction.

Binding affinity alone does not determine the significance of a given SH3–ligand complex, and weak SH3 interactions may also be functionally important. Nevertheless, we reasoned that superior binding affinities of SH3–ligand complexes would rarely have evolved fortuitously and be irrelevant, and wanted to develop a method for objective and comprehensive identification of optimal SH3–ligand pairs. Previous work by us and others has established filamentous phage-display as a useful strategy for presentation of functional SH3 domains (Hiipakka et al, 1999; Panni et al, 2002). Therefore, we chose to generate a library in which all human SH3 domains were expressed on the surface of M13 bacteriophages. This enabled us to use full-length SH3 target proteins or relevant native domains of them as ligands for rapid and unbiased screening of the SH3 domains with the highest affinity for them.

Results and Discussion

Human SH3 phage library

Thorough analyses of SH3 domain sequences identified by the SMART and PFAM algorithms and extensive BLAST searches with representative SH3 domains were carried out to generate an essentially complete and non-redundant collection of human SH3 domain sequences. Carboxy-terminal assignment by SMART and PFAM was modified in the case of a few atypical SH3 domains on the basis of manual alignment to ensure sequence continuity across the last two β-strands and the 310-helix between them. On the basis of the unusual split organization of the PSD-95 SH3, shown by the X-ray structure by McGee et al (2001), however, it seems that some MAGUK family SH3 sequences in our collection are defective in the last β-strand of the SH3 fold.

Single amino-acid variants of the same SH3 domains were often found, some of which may be true polymorphisms, but only the most prevalent sequence was included in our collection. By contrast, splice variants were considered as independent SH3 domains. Six such splice variants were included in our collection, which altogether consists of 296 different SH3 domains. As some proteins contain up to six individual SH3 domains, the total number of human genes encoding SH3 domains was found to be 217. Although it is possible that we have missed a few SH3 domains, and/or that some sequences included do not encode bona fide SH3 domains, we are confident that this number is not far from correct. Sequences of all these 296 SH3 domains together with links to relevant bioinformatic information are electronically available as supplementary information online.

Codon-optimized genes encoding all but 15 (supplementary information online) of these 296 SH3 domains were cloned into an M13-derived phagemid vector fused to pVIII gene. These phagemids were transformed into Escherichia coli and individual recombinant phage supernatants generated by helper phage infection and their titres normalized to 1011 infectious units per millilitre. These were mixed in equal ratios to assemble a library containing all phages at the same titre.

Lessons from HIV-1 Nef

SH3 binding capacity of HIV-1 Nef is important for its functionality. A canonical SH3 binding motif together with molecular contacts involving a hydrophobic pocket in Nef mediates strong binding to Hck-SH3 (KD 250 nM; Lee et al, 1995, 1996). Other SH3-containing proteins, including Lyn, Fyn, Src, Lck and Vav, can also bind to Nef, but with lower affinities (Arold et al, 1998). As Hck is expressed in macrophages but not in T lymphocytes, the relevant SH3 partner of Nef in T cells has remained an unresolved question.

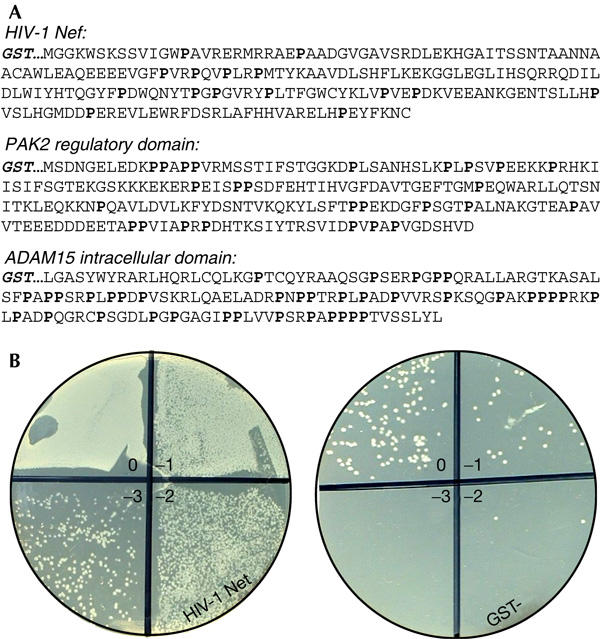

We coated six-well plates with Nef expressed as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein, and let phages in the library to compete for binding to it. E. coli were infected with phages that remained bound to Nef after washing, and plated at serial dilutions on ampicillin plates. As shown in Fig 1, GST–Nef bound markedly more SH3 phages than did plain GST protein. Remarkably, all of the more than 30 sequenced clones picked from this plate contained the SH3 domain of Hck.

Figure 1.

Target proteins used in this study and an example of results from human Src homology-3 phage library screening. (A) Sequences of the Src homology-3 (SH3) target proteins used for phage selection, with proline residues highlighted. (B) Outcome of a typical screening experiment with HIV-1 Nef. Phages bound to glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Nef or plain GST were used to infect Escherichia coli cells subsequently plated as tenfold dilutions onto ampicillin plates.

To see whether other SH3 domains could be specifically selected in the absence of Hck, we prepared a similar infectious library that contained all other SH3 phages except for Hck (and the related Lyn). Use of the Hck−/Lyn− SH3 library resulted in poor enrichment of phages in the Nef-coated wells, even on several such rounds of selection and amplification (data not shown). After four or more rounds of selection, certain SH3 domains, such as the third SH3 of Tuba, the second SH3 of protein Crk and the SH3 of a predicted protein dubbed 7A5 (NP_877439), occasionally accounted for most of the sequence clones. However, the outcome of these experiments was variable, indicating that none of the SH3 domains in the Hck−/Lyn− library bound Nef with an affinity sufficient to consistently direct phage selection.

These studies were informative, although they did not show strong candidates for novel cellular partners for Nef. They confirmed that Hck is indeed the preferred SH3 target of HIV-1 Nef, and suggested that T cells do not encode a postulated ‘Hck-like' high-affinity SH3 ligand for Nef. It could be speculated that although catalytic activation of Hck in macrophages by disruption of an intramolecular SH3 interaction calls for strong binding (Moarefi et al, 1997), the role of SH3-directed protein complexes of Nef in T cells may be fundamentally different and not require such tight binding. The failure of Nef to select Fyn, Src or Lck SH3 domains despite their established binding affinities for Nef ranging from 10.6 μM (Lck) to 15.8 μM (Fyn; Arold et al, 1998) indicated that an affinity value at least in the low micromolar range was necessary for positive selection of specific SH3 phages in this system.

SH3 partners of PAK2

p21-activated kinases (PAKs) are important signalling molecules involved in the regulation of actin cytoskeleton, apoptosis and malignant transformation (Bokoch, 2003). To characterize the SH3 proteins that preferentially interact with the amino-terminal regulatory domain of PAK2, we used a GST fusion protein containing PAK2 residues 1–212 (Fig 1A) as bait. The identity of bound SH3 phages was determined after two rounds of selection. Sequencing of 17 clones derived from two independent experiments showed that most (13 out of 17) of these SH3 domains belonged to β-PIX. The remaining four clones were α-PIX, vinexin-III/III (III/III denotes the third of three SH3 in this protein) and two copies of an SH3 protein of a predicted protein dubbed FLJ00204. We found FLJ00204 to be a fragment of a larger gene product that could be assembled in silico, which we re-named POSH2 because of its close similarity to the adapter protein POSH (plenty of SH3 domains; Tapon et al, 1998). Like POSH, POSH2 contains four SH3 domains, the third of which bound to PAK2.

We then generated an SH3 library specifically lacking α-PIX and β-PIX. A total of 29 clones from two independent experiments with the PIX-negative library were sequenced. Half of these (15 out of 29) contained Nckα-II/III. Ponsin-III/III was found five times, vinexin-III/III three times and ArgBP2-III/III twice. Notably, these three proteins are highly related, and SH3-III/III of the vinexin-ponsin-ArgBP2 family thus accounted for a third (10 out of 29) of these clones. The remaining SH3 domains were Src, Hck, Grb2-I/II and POSH2-III/IV (one of each).

It was gratifying to note that these PAK2-selected SH3 domains represented novel but also well-established PAK-interacting proteins. The role of PIX and Nck proteins in the regulation of PAK activity has been shown, and is mediated by a high-affinity recognition of atypical peptide motifs in PAK (Manser et al, 1998; Zhao et al, 2000). Binding of Grb2 to PAK1 has also been suggested to be important in growth factor signalling (Puto et al, 2003). During the preparation of this manuscript, Yuan et al (2005) reported an antiapoptotic role for ArgBP2 as an adapter that can bind to both PAK1 and Akt. Our results support this finding, but also implicate the involvement of the other members of the vinexin-ponsin-ArgBP2 family in PAK function. A direct Src–PAK interaction has not been reported, but tyrosine phosphorylation and an increase in catalytic activity of PAK2 have been observed in cells overexpressing Src kinases (Renkema et al, 2002). On the basis of our present results, it is tempting to speculate that this regulation may depend on a direct SH3-guided PAK–Src interaction.

SH3 domains selected by ADAM15

ADAM15 belongs to the adamalysin metalloproteinase disintegrins, many of which contain proline-rich intracellular tails that can interact with many SH3 proteins, including those of the Src family (Suzuki et al, 2000). Nevertheless, the role of SH3 binding in ADAM function is unknown, and their relevant SH3 partners remain to be established.

The intracellular region of ADAM15 (Fig 1A) fused to GST bound well to SH3 phages in the library. The identity of 18 clones after one round and 16 clones after two rounds of selection from two independent experiments was determined. Two different SH3 domains, one belonging to nephrocystin, a protein defective in a hereditary kidney disease (Hildebrandt et al, 1997), and the other to a predicted protein dubbed MGC32065, predominated after the first selection (5 out of 18 and 11 out of 18, respectively), and were almost exclusively found after two rounds of selection (6 out of 16 and 9 out of 16, respectively). The two other SH3 clones picked after a single affinity selection were N-Src and FISH-I/V.

With the exception of FISH (Abram et al, 2003), these proteins have not been reported to bind to any of the ADAMs, although proteins homologous with them, such as other Src family members, bind. Moreover, we noted that MGC32065 contains a combination of PX and SH3 domains and shows significant overall homology to members of the sorting nexin (SNX) family, including SNX9/SH3PX1, which has been reported to bind to ADAMs 9 and 15 (Howard et al, 1999). As human or mouse genes dubbed up to SNX29 could be found in databases, MGC32065 was re-named as SNX30.

Biochemistry of the interactions

To study the affinity and specificity of the discovered SH3 interactions, a semiquantitative protein interaction assay was developed. Altogether, 22 SH3 domains, including those found in the current library screens and their homologues, as well SH3 domains reported in the literature to interact with Nef, PAK or ADAM proteins were expressed as GST fusion proteins, labelled and used to probe wells coated with these three target proteins, which were expressed free of a GST moiety to minimize any artefacts due to GST oligomerization. A representative experiment in which these proteins were probed in parallel with twofold dilutions (5.0–0.04 μM) of eight relevant SH3 domains is shown in Fig 2A. Binding of all 22 SH3 domains to each of the three target proteins was similarly examined, creating a matrix of 66 measured interactions (Fig 3).

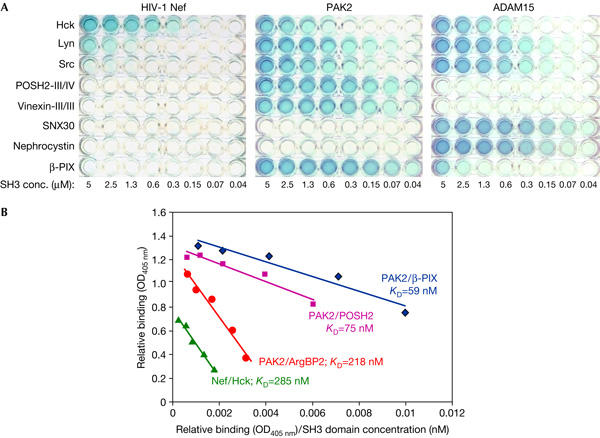

Figure 2.

Recombinant protein binding assay for analysis of Src homology-3 (SH3)–ligand protein interactions. (A) Four maltose-binding protein- or His-tagged ligand proteins were probed with a panel of ten labelled glutathione S-transferase–SH3 proteins. (B) Scatchard plot fitting of binding data of Nef/Hck-SH3 and three SH3 interactions of P21-activated kinase (PAK)2.

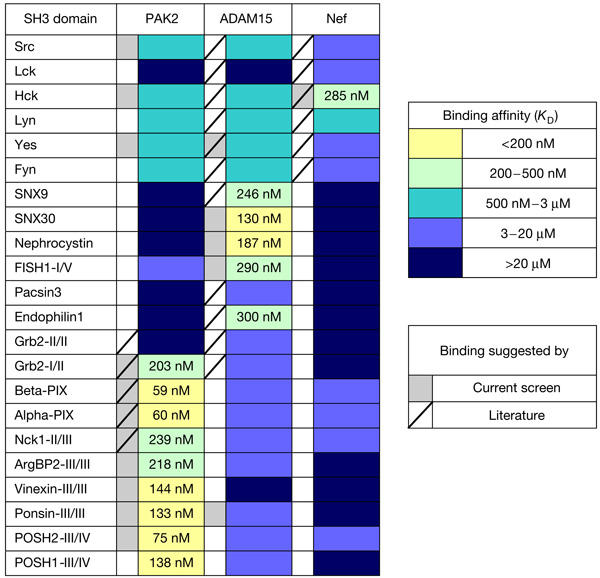

Figure 3.

A matrix showing of binding of 22 selected Src homology-3 (SH3) domain proteins to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 Nef, P21-activated kinase (PAK)2 and ADAM15. Binding affinities were estimated as explained in the text, and classified into five colour-coded categories. The absolute affinity values for the two strongest categories are also shown in the matrix. Interactions identified in the present screen are indicated by grey shading of the box left to the corresponding column. A tilted line in this box indicates that this interaction has been reported in the literature.

In case of stronger interactions (KD<0.5 μM), the data points from serial SH3 dilutions could be nicely fitted on linear lines in Scatchard plots, and the apparent KD values derived from these slopes (Fig 2B). This fit, together with a good correlation between the published values and the KD values measured for PAK/β-PIX (24 nM; Manser et al, 1998) and Nef/Hck (Lee et al, 1995) complexes here, indicated that the assay was valid and useful for estimation of binding affinities for these interactions. Despite their dose-dependent binding signals, modelling of weaker interactions by Scatchard plots was more problematic. Therefore, these interactions were assigned to two broad categories corresponding to estimated affinities in the range of 0.5–3 and 3–20 μM. Interactions that were weaker than binding of Nef to Fyn-SH3 (KD 15.8 μM; Arold et al, 1998) or too weak to be detected at an SH3 concentration of 38 μM were assigned to a remaining category defined by a KD value >20 μM (Fig 3).

The results from this assay agreed well with our phage library screening. All SH3 domains that were included because of their selection from the library bound their specific target proteins with high affinity (KD<0.5 μM). A good correlation between the measured binding affinity and the frequency of selection of the corresponding SH3 from the library could also be observed. PIX SH3 domains were the preferred targets of PAK2, as judged by their preferential selection and their measured affinities, which also agrees well with the published literature. Conversely, our data also showed the capacity of PAK2 to bind tightly to other SH3 domains as well, most notably the C-terminal SH3 of the vinexin-ponsin-ArgBP2 family and the third SH3 of the POSH proteins. Similarly, the SH3 clones that were predominantly selected by ADAM15, namely two interesting and novel ADAM binders nephrocystin and SNX30, also showed the highest affinity in the protein binding assay.

Remarkably, these strong interactions also seemed to be highly specific, as only modest or no binding was observed for the vinexin-ponsin-ArgBP2 and POSH family SH3 domains to ADAM15 or Nef, or SNX30 or nephrocystin SH3 domains to PAK2 or Nef, despite the presence of ideal SH3 binding consensus motifs in all of these proteins. Conversely, some SH3 domains had a rather promiscuous binding pattern, such that Hck and Lyn bound relatively well to all three target proteins tested.

Conclusions

We have generated a non-redundant and apparently complete collection of human SH3 domain sequences (supplementary information online), and developed a phage-display-based tool for objective identification of SH3 domains that show strongest binding to target proteins of interest.

Studies using HIV-1 Nef, PAK2 and ADAM15 as ligands confirmed several known high-affinity SH3 interactions, and identified new and potentially important SH3 partners for PAK2 and ADAM15. These data provide strong experimental support for the rationale and general feasibility of this approach, and point to interesting new directions for further research on PAK and ADAM family proteins.

As SH3 domains are often considered as low-affinity binding modules, it is worth noting that when presented a complete set of human SH3 domains, each of the three ligand proteins tested found cognate SH3 domains binding to them with nanomolar affinities. Besides supporting the idea that these novel interactions might serve important cellular functions, this strong binding also suggests involvement of binding determinants in PAK2 and ADAM15 that are not confined to short PxxP motif-containing peptides. By comparison, the apparent KD values of the strongest interactions discovered by a large screen that examined binding of thousands of predicted SH3-binding peptides to a panel of different SH3 domains ranged from 1 to 100 μM, most of the values being higher than 10 μM (Landgraf et al, 2004).

Because of the capacity of the SH3 phage library system to show SH3 interactions with nanomolar affinity and high selectivity, as shown here for Nef, PAK2 and ADAM15, it should be a valuable tool for further efforts aiming at systematic deciphering of the wiring of cellular SH3-mediated signalling networks.

Methods

GeneOptimizer™ software (GENEART GmbH) was used to design codon-optimized DNA coding sequences for a synthetic library of human SH3 domains. These genes were generated by the assembly of oligonucleotides by a single-step PCR-based method, and ligated between KpnI and SacI sites in pCR-Script (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The resulting colonies were screened by sequencing to obtain clones with correct sequences. These SH3 clones were inserted between BssH2 and NotI in the multivalent phage-display vector pG8JH (a derivative of pG8H6; Jacobsson & Frykberg, 1996) by PCR-assisted cloning and verified by sequencing. Infectious phage libraries were generated using M13KO7 helper phage and screened with immobilized proteins, as described (Hiipakka et al, 1999).

GST–SH3 fusion vectors were generated by transferring the SH3 fragments from the pCR-Script clones into pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). For GST–Nef vector, see Hiipakka et al (1999). The vector for His-tagged PAK2 was created by inserting a fragment coding for PAK2 residues 1–212 into Nhe1–Xho1 sites of pET23d (Novagen, EMD Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany). Maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion constructs were generated by cloning the relevant ADAM15 and Nef sequences into pMAL-c2 (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) using PCR. Expression and purification of all these fusion proteins were carried out according to the manufacturers instructions.

MaxiSorp F8 strips (Nunc) were coated with MBP–Nef, MBP–ADAM15 or PAK2–His protein (200 ng in 50 μl per well) overnight at 4°C, followed by 1 h incubation with 1.5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at 20°C and three washes with washing buffer (WB; TBS+0.05% Tween 20). GST–SH3 domains were conjugated to horseradish peroxidase by incubation for 1 h on ice with 100 μg/ml glutathione–horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Labelled GST–SH3 domains were serially diluted in TBS+1.5% BSA+2 mM dithiothreitol and added to the wells. After a 1.5 h incubation at 20°C, the wells were washed three times with WB, and 50 μl of substrate reagent 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline)-6-sulphonic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was added per well. Enzymatic reactions were stopped after 10 min by adding 50 μl of 1% SDS, followed by optical density measurement at 405 nm.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/7400596-s1.pdf).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Lehtinen for expert technical assistance, the rest of the Geneart team and Saksela lab for cooperation and support, and B. Mayer for comments and critical reading of the manuscript. This study has been supported by the Academy of Finland (grants 53913 to K.S. and 203434 & 202423 to G.H.R.), the Medical Research Council of Tampere University Hospital (grants 9F068 to K.S. and 9E056 to G.H.R.) and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation (K.S.). S.K. was supported by the Tampere Graduate School in Biomedicine and Biotechnology.

References

- Abram CL, Seals DF, Pass I, Salinsky D, Maurer L, Roth TM, Courtneidge SA (2003) The adaptor protein fish associates with members of the ADAMs family and localizes to podosomes of Src-transformed cells. J Biol Chem 278: 16844–16851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arold S, O'Brien R, Franken P, Strub MP, Hoh F, Dumas C, Ladbury JE (1998) RT loop flexibility enhances the specificity of Src family SH3 domains for HIV-1 Nef. Biochemistry 37: 14683–14691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokoch GM (2003) Biology of the p21-activated kinases. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 743–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannetti B, Via A, Cestra G, Cesareni G, Helmer-Citterich M (2000) SH3-SPOT: an algorithm to predict preferred ligands to different members of the SH3 gene family. J Mol Biol 298: 313–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiipakka M, Poikonen K, Saksela K (1999) SH3 domains with high affinity and engineered ligand specificities targeted to HIV-1 Nef. J Mol Biol 293: 1097–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt F, Otto E, Rensing C, Nothwang HG, Vollmer M, Adolphs J, Hanusch H, Brandis M (1997) A novel gene encoding an SH3 domain protein is mutated in nephronophthisis type 1. Nat Genet 17: 149–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard L, Nelson KK, Maciewicz RA, Blobel CP (1999) Interaction of the metalloprotease disintegrins MDC9 and MDC15 with two SH3 domain-containing proteins, endophilin I and SH3PX1. J Biol Chem 274: 31693–31699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson K, Frykberg L (1996) Phage display shot-gun cloning of ligand-binding domains of prokaryotic receptors approaches 100% correct clones. Biotechniques 20: 1070–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf C, Panni S, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Castagnoli L, Schneider-Mergener J, Volkmer-Engert R, Cesareni G (2004) Protein interaction networks by proteome peptide scanning. PLoS Biol 2: E14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Leung B, Lemmon MA, Zheng J, Cowburn D, Kuriyan J, Saksela K (1995) A single amino acid in the SH3 domain of Hck determines its high affinity and specificity in binding to HIV-1 Nef protein. EMBO J 14: 5006–5015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Saksela K, Mirza UA, Chait BT, Kuriyan J (1996) Crystal structure of the conserved core of HIV-1 Nef complexed with a Src family SH3 domain. Cell 85: 931–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias MJ, Wiesner S, Sudol M (2002) WW and SH3 domains, two different scaffolds to recognize proline-rich ligands. FEBS Lett 513: 30–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manser E, Loo TH, Koh CG, Zhao ZS, Chen XQ, Tan L, Tan I, Leung T, Lim L (1998) PAK kinases are directly coupled to the PIX family of nucleotide exchange factors. Mol Cell 1: 183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer BJ, Saksela K (2004) SH3 domains. In Structure and Function of Modular Protein Domains, Cesareni G, Gimona M, Sudol M, Yaffe M (eds) pp 37–58. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH [Google Scholar]

- McGee AW, Dakoji SR, Olsen O, Bredt DS, Lim WA, Prehoda KE (2001) Structure of the SH3-guanylate kinase module from PSD-95 suggests a mechanism for regulated assembly of MAGUK scaffolding proteins. Mol Cell 8: 1291–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moarefi I, LaFevre-Bernt M, Sicheri F, Huse M, Lee CH, Kuriyan J, Miller WT (1997) Activation of the Src-family tyrosine kinase Hck by SH3 domain displacement. Nature 385: 650–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panni S, Dente L, Cesareni G (2002) In vitro evolution of recognition specificity mediated by SH3 domains reveals target recognition rules. J Biol Chem 277: 21666–21674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puto LA, Pestonjamasp K, King CC, Bokoch GM (2003) p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) interacts with the Grb2 adapter protein to couple to growth factor signaling. J Biol Chem 278: 9388–9393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkema GH, Pulkkinen K, Saksela K (2002) Cdc42/Rac1-mediated activation primes PAK2 for superactivation by tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 22: 6719–6725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Kadota N, Hara T, Nakagami Y, Izumi T, Takenawa T, Sabe H, Endo T (2000) Meltrin α cytoplasmic domain interacts with SH3 domains of Src and Grb2 and is phosphorylated by v-Src. Oncogene 19: 5842–5850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapon N, Nagata K, Lamarche N, Hall A (1998) A new rac target POSH is an SH3-containing scaffold protein involved in the JNK and NF-κB signalling pathways. EMBO J 17: 1395–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong AH et al. (2002) A combined experimental and computational strategy to define protein interaction networks for peptide recognition modules. Science 295: 321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan ZQ, Kim D, Kaneko S, Sussman M, Bokoch GM, Kruh GD, Nicosia SV, Testa JR, Cheng JQ (2005) ArgBP2γ interacts with Akt and p21-activated kinase-1 and promotes cell survival. J Biol Chem 280: 21483–21490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZS, Manser E, Lim L (2000) Interaction between PAK and nck: a template for Nck targets and role of PAK autophosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 20: 3906–3917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information