Summary

Workshop on Mechanisms and Regulation of mRNA Turnover

Keywords: AU-rich element, decapping, deadenylation, miRNA, nonsense-mediated decay

Introduction

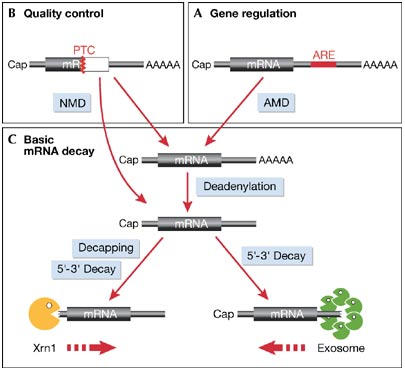

The control of messenger RNA turnover is increasingly being recognized as having a crucial role in the regulation of gene expression (Wilusz & Wilusz, 2004). The stability of mRNAs is known to vary during development and also in response to environmental factors, such as cell stress and pro-inflammatory stimuli. Once exported from the nucleus, most mRNAs are relatively stable in the cytoplasm (with half-lives >10 h in mammalian cells); however, a subset of mRNAs decays rapidly (with half-lives between 15 min and 2 h). The rapid decay of these mRNAs is determined by specific destabilizing elements, the most widespread of which is a heterogeneous group of AU-rich elements (AREs) located in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of an estimated 8% of all mRNAs (Khabar, 2005). ARE-mediated mRNA decay (AMD; Fig 1A) requires a set of RNA-binding proteins that recognize the ARE and target the mRNA to the basic decay machinery (Fig 1C). As many ARE-containing mRNAs encode proteins involved in inflammation, AMD can be viewed as a ‘post-transcriptional operon' (Keene & Tenenbaum, 2002), a term that refers to the general observation that RNA-binding proteins tend to coordinately regulate groups of mRNAs that encode proteins with a common function.

Figure 1.

General scheme of messenger RNA decay pathways. (A) The regulation of gene expression involves the control of mRNA degradation at the post-transcriptional level. mRNAs containing an AU-rich element (ARE) in their 3′ untranslated region (UTR) undergo rapid ARE-mediated mRNA decay (AMD) in resting cells. Stabilization of ARE-containing mRNAs by various stimuli contributes to the induction of gene expression. (B) Quality control mechanisms activate mRNA degradation. mRNAs that contain a premature termination codon (PTC) are recognized and specifically degraded by the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway. (C) The basic mRNA decay machinery in the cytoplasm initially removes the poly(A) tail through the activity of deadenylating enzymes. Subsequently, the mRNA can be further degraded from the 3′ end by a complex of 3′–5′ exonucleases known as the exosome. Alternatively, the mRNA is decapped at the 5′ end, and the 5′–3′ exonuclease Xrn1 proceeds to degrade the body of the mRNA.

The EMBO Workshop on Mechanisms and Regulation of mRNA Turnover took place in the remote mountain valley of Arolla, Switzerland, from 28 August to 1 September 2005. The workshop was organized by C. Clayton, W. Filipowizc, R. Gherzi and C. Moroni, and was supported by EMBO, the Kontaktgruppe für Forschungsfragen (Ciba Spezialitätenchemie, Roche, Novartis, Serono and Syngenta), and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

The importance of mRNA turnover is revealed by the phenotypes of animals or plants in which the expression of genes involved in controlling mRNA stability has been disrupted. For example, mice that are deficient for tristetrapolin (TTP)—an ARE-binding protein required for the rapid degradation of mRNAs that encode cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα), granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-2 (IL-2)—develop a systemic inflammatory syndrome with autoimmunity and myeloid hyperplasia (Carrick et al, 2004). In Caenorhabditis elegans, knockdown of the main 5′–3′ exoribonuclease xrn-1 results in defects in ventral enclosure during embryogenesis (Newbury & Woollard, 2004). Finally, the Arabidopsis thaliana mutant for downstream 1, which regulates the mRNA stability of cinnamoyl CoA reductase-like (CCR) and senescence-associated gene 1, have defects in their circadian rhythm (Lidder et al, 2005).

Apart from regulating gene expression levels, mRNA turnover also has a crucial role in mRNA quality control. The mRNAs that harbour a premature termination codon (PTC) are recognized and degraded rapidly through the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway (Fig 1B). NMD thereby reduces the production of truncated proteins, which are potentially detrimental to the cell as they can interfere with the function of the corresponding full-length proteins. Although PTCs seem to be recognized by a mechanism that is entirely different from the recognition of AREs, recent results indicate that both the AMD and NMD pathways deliver the targeted mRNAs to the same basic decay machinery (Baker & Parker, 2004; Wilusz & Wilusz, 2004).

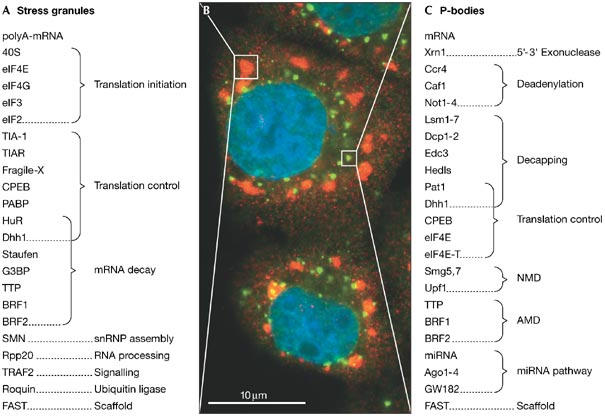

Control of mRNA stability is intimately linked with the regulation of translation. Actively translated, polysome-associated mRNAs are protected from degradation by proteins that prevent ribonucleases from accessing the ends of the mRNA: the cap-binding protein eIF4E protects the 5′ end, and the poly(A)-binding protein protects the 3′ end. When initiation of translation is repressed, remaining ribosomes run off the mRNA, which then enters the pool of translationally silenced mRNAs. From this intermediate state, mRNAs can either re-enter the pool of translated mRNA, or move towards their ultimate destination of being degraded. Work during the past few years has shown that mRNA localizes to specific subdomains in the cytoplasm as it moves between its different states (Brengues et al, 2005; Kedersha & Anderson, 2002). Polysome-associated mRNAs are localized throughout the cytoplasm and at endoplasmic reticulum membranes. In cells that have been subject to environmental stress, a general arrest of translation causes mRNAs to aggregate in large cytoplasmic structures known as stress granules (Fig 2A,B). Finally, mRNAs targeted for degradation are located in processing (P)-bodies, which are small cytoplasmic foci that contain many of the enzymes of the basic decay machinery (Fig 2B,C). Recent data show that mRNAs subject to translational silencing after base pairing with microRNAs (miRNAs) are also targeted to P-bodies (Liu et al, 2005; Pillai et al, 2005), a finding that emphasizes the tight relationship between the control of translation and the control of mRNA stability.

Figure 2.

Stress granules and processing bodies have a central role in controlling messenger RNA translation and stability. (A) Stress granules contain aggregates of translationally stalled poly(A)-mRNA, pre-initiation complexes including the small 40S ribosomal subunit, as well as various RNA-binding proteins involved in regulating the translation and decay of specific mRNAs. Note that stress granules have not been observed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (B) Immunofluorescence micrograph of human HeLa cells that were subject to oxidative stress by treatment with arsenite. Fixed cells were stained in red with a polyclonal eIF4E antibody (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA) and in green with a human auto-antiserum that recognizes GW182 (kindly provided by M.J. Fritzler, University of Calgary, AB, Canada). Nuclei were stained in blue with Hoechst dye. Areas delineated by boxes show a stress granule (red) and a processing (P)-body (green, with partial yellow overlap). (C) P-bodies contain components of the basic mRNA degradation machinery and are thought to be the actual sites of mRNA decay. P-body-associated proteins suppress translation, induce mRNA deadenylation, decapping and 5′–3′ exonucleolytic degradation. P-bodies also contain proteins that are required for specific mRNA degradation pathways such as nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), ARE-mediated mRNA decay (AMD) and microRNA (miRNA)-directed gene silencing. P-bodies are found in both yeast and mammalian cells.

In this summary of the recent EMBO Workshop on Mechanisms and Regulation of mRNA Turnover, we focus on those areas of research in which important and exciting discoveries have recently been made. These include the role of P-bodies, insights into the decapping and deadenylation machinery, unexpected functions of Xrn1-mediated 5′–3′ degradation, the regulation of AMD by protein phosphorylation and a reflection on controversial models of NMD.

Control of deadenylation

In eukaryotes, deadenylation is the first step in the general degradation of mRNAs (Fig 1C; reviewed in Parker & Song, 2004). Shortening of the long poly(A) tail to 10–60 nucleotides requires the activity of deadenylases such as the Ccr4–Not complex, the Pan2/3 complex or the poly(A)-specific ribonuclease (PARN). Once the poly(A) tail has been shortened, two independent mechanisms account for the subsequent degradation of the mRNA. At the 3′ end, a large complex of exonucleases and helicases, known as the exosome, can further degrade the mRNA in the 3′–5′ direction. At the 5′ end, the 7-methyl guanosine (7mG) cap is removed by decapping enzymes, which allows the exoribonuclease Xrn1 to degrade the body of the mRNA in the 5′–3′ direction.

Several talks at the meeting shed light on the control and specificity of deadenylation. J. Wilusz (Fort Collins, CO, USA) showed that the process of in vivo polyadenylation leads to the deposition of the RNA-binding protein nucleophosmin on the mRNA. Importantly, poly(A) tails artificially transcribed from a DNA template do not cause the recruitment of nucleophosmin. Although the exact role of nucleophosmin is not yet understood, its deposition on mRNA underlines the concept that proteins mark the history of every mRNA and thereby influence its fate. Wilusz presented further evidence that a protein called CUG-binding protein binds to certain 3′ UTRs and induces rapid poly(A) tail shortening in cell extracts. E. Wahle (Halle, Germany) presented another example of sequence-specific deadenylation using a cell-free system from Drosophila melanogaster embryos. The nanos mRNA, which encodes a protein crucial for posterior determination in D. melanogaster embryos, is regulated in vivo by the protein Smaug, and the Smaug-binding site is essential for rapid deadenylation. These two examples illustrate that the rate at which an mRNA is deadenylated can be controlled in a sequence-specific manner by RNA-binding proteins.

In contrast to the stabilizing role of poly(A) tails in the cytoplasm, B. Seraphin (Gif sur Yvette, France) presented evidence that addition of poly(A) induces the degradation of some nuclear RNAs (Wyers et al, 2005). A recently identified poly(A) polymerase (the catalytic subunit of which is known as Trf4 in yeast) adds short poly(A) tails to certain nuclear transcripts, thereby marking these RNAs for subsequent degradation by the exosome. Nuclear transcripts degraded through this mechanism include cryptic unstable transcripts, which are transcribed by RNA polymerase II from intergenic regions, and the function of which is unknown. This mode of inducing the decay of RNAs by the addition of a short poly(A) tail (Kadaba et al, 2004; LaCava et al, 2005; Vanacova et al, 2005; Wyers et al, 2005) is reminiscent of how mRNA degradation is initiated in bacteria, suggesting an ancient degradation mechanism.

Control of decapping

After deadenylation, the next key step in the degradation of mRNA is the removal of the 7mG cap by the decapping enzymes Dcp1 and Dcp2. In mammals, Dcp1 seems to be an activator of decapping, whereas Dcp2, which contains a Nudix motif found in several pyrophosphatases, catalyses the actual decapping reaction. The remaining monophosphorylated mRNA is then degraded progressively by the exoribonuclease Xrn1. J. Lykke-Andersen (Boulder, CO, USA) identified components of P-bodies that are involved in mRNA decapping, including a protein that enhances decapping known as Hedls (Fenger-Gron et al, 2005). In addition, he showed that the protein TTP activates decapping of ARE-containing RNA. M. Kiledjian (Rutgers, NJ, USA) presented a recently identified regulator of decapping, a protein that interacts with Dcp2 and inhibits decapping activity in vitro. As this protein seems to be expressed only in testis, this is the first example that decapping might be regulated in a tissue-specific manner.

Xrn1-dependent mRNA decay

For a long time, investigators have puzzled over the question whether mRNAs are primarily degraded in the 5′–3′ or the 3′–5′ direction. Through genetic approaches and trapping of decay intermediates, evidence has been provided that, in yeast, the main mRNA decay pathway is 5′–3′ degradation. In higher eukaryotes, the question is more difficult to answer as decay intermediates escape detection. Biochemical studies using cellular extracts show that in vitro the 3′–5′ decay pathway predominates (Wilusz & Wilusz, 2004). However, recent data presented at the meeting, using classical genetics or RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown techniques, indicate that in vivo the 5′–3′ pathway has an important role in all eukaryotes. G. Stoecklin (Boston, MA, USA) used small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in human cells to analyse in which direction an ARE-containing reporter mRNA is degraded. Downregulation of Xrn1 stabilized an ARE-containing mRNA, whereas downregulation of exosome components had little effect on AMD (Stoecklin et al, 2005). C. Clayton (Heidelberg, Germany) showed that downregulation of two out of the four XRN1 homologues, XRNA and XRNB, in the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei stabilizes mRNAs and results in cell death. In D. melanogaster, S. Newbury (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) reported that mutations in the Xrn1 orthologue pacman cause developmental abnormalities such as low fertility, gastrulation defects and defects at thorax closure. Thorax closure is a conserved morphological process that involves a coordinated movement of the epithelium known as ‘epithelial sheet sealing', a process that is similar to wound healing in humans. Previous data from Newbury's group showed that downregulation of xrn-1 in C. elegans results in defects in embryonic ventral enclosure (Newbury & Woollard, 2004), a related morphological process. These data suggest that pacman/xrn-1 targets a specific subset of mRNAs that are involved in changes in cell shape.

Silent mRNA in P-bodies and stress granules

One of the most exciting recent discoveries in the field of mRNA turnover is that mRNA degradation in the cytoplasm seems to take place in specific particles known as P-bodies. In both yeast and human cells, P-bodies have been shown to harbour many enzymes of the basic decay machinery (Fig 2B,C), including deadenylating enzymes, the decapping complex and the 5′–3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1. Recent studies have shown that mRNA itself can be visualized in P-bodies when mRNA degradation is inhibited (Cougot et al, 2004; Sheth & Parker, 2003), suggesting that P-bodies are actual sites of mRNA decay. P-bodies are dynamic structures that increase dramatically both in size and in number in response to different forms of stress such as energy deprivation or heat shock.

In his keynote lecture, R. Parker (Tuscon, AZ, USA) presented evidence that the helicase Dhh1 and the Pat1 protein have important roles as inhibitors of translation (Coller & Parker, 2005). Strikingly, yeast cells that are deficient for Dhh1 and Pat1 can no longer reduce their translation rate in response to stress. In addition, overexpression of Dhh1 or Pat1 is sufficient to induce translational silencing. As Dhh1 and Pat1 were identified initially as activators of decapping in yeast and are localized in P-bodies, this suggests a fundamental reciprocal regulation of mRNA translation and decay. These data also indicate that P-bodies in yeast might be where mRNA is not only degraded, but also relocated after translational arrest (Brengues et al, 2005).

In mammalian cells, translationally silenced mRNAs accumulate in stress granules, which are cytoplasmic aggregates distinct from P-bodies (Fig 2). Stress granules are not present under normal conditions, but form as a result of environmental stress such as heat shock, oxidative stress or energy deprivation (Kedersha & Anderson, 2002). Messenger RNA in stress granules remains polyadenylated; by storing translation initiation factors, small 40S ribosomal subunits and mRNAs together in one location, the cell is prepared for a rapid return to active translation as soon as the stress is removed. However, stress granules also seem to be sites where mRNAs are selected for degradation, as indicated by the observation that TTP, an RNA-binding protein essential for AMD, is recruited to stress granules in its active (non-phosphorylated) form, but excluded from stress granules in its inactive (phosphorylated) form (Stoecklin et al, 2004).

To examine the relationship between P-bodies and stress granules, P. Anderson (Boston, MA, USA) presented fascinating movies of live mammalian cells, showing that P-bodies and stress granules physically interact during certain types of stress. Whereas stress granules are fairly static structures, P-bodies move quickly in the cytoplasm and make transient contacts with stress granules. Overexpression of TTP causes P-bodies to cluster tightly around stress granules, emphasizing that the control of translation and mRNA decay seem to be coupled at the morphological level (Kedersha et al, 2005).

P-bodies also harbour argonaute proteins (Liu et al, 2005), which are central to the effector complex of siRNA- and miRNA-directed gene silencing. The intimate link between translation and decay was re-enforced by data from W. Filipowicz's group (Basel, Switzerland), who showed that the silencing of gene expression by miRNAs occurs through the inhibition of translation initiation, and that the mRNAs targeted by miRNAs are recruited to P-bodies (Pillai et al, 2005). As the inhibited mRNAs were found to undergo only limited degradation, it seems that mammalian P-bodies can also act as storage compartments for translationally repressed mRNAs, in addition to their role in mRNA degradation. Earlier studies had also shown that components of the NMD pathway, such as Upf1, also localize to P-bodies (Fukuhara et al, 2005). It therefore seems that the apparently unrelated pathways of AMD, NMD and miRNA-directed gene silencing share the ability to deliver their target mRNAs to the same basic machinery that controls translation and mRNA decay in P-bodies.

AMD: phosphorylation is key

AMD is a powerful regulatory system that limits the expression of a defined subset of mRNAs containing an ARE in their 3′ UTR (Fig 1A). AMD is induced by RNA-binding proteins such as TTP, butyrate response factor 1 (BRF1), AU-rich element RNA-binding factor 1 (AUF1) and KH-type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP), which recognize AREs and subsequently deliver the mRNA to the basic decay machinery (Dean et al, 2004). In T cells and macrophages, pro-inflammatory signals inhibit AMD, which contributes to the transient induction of ARE-containing mRNAs encoding various cytokines and chemokines. In these cells, AMD is mainly inhibited through activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)–MK2 pathway. MK2 phosphorylates TTP at two serine residues, which leads to the binding of 14-3-3 adaptor proteins and partially inhibits the ability of TTP to destabilize its target mRNAs (Stoecklin et al, 2004). A. Clark (London, UK) pointed out that phosphorylation of TTP by MK2 also promotes export of TTP from the nucleus into the cytoplasm of macrophages, and that it further prevents the proteolytic degradation of TTP (Brook et al, in press). Similarly, C. Moroni (Basel, Switzerland) showed that phosphorylation of the TTP-related protein BRF1 at two specific serine residues not only inhibits its destabilizing activity (Schmidlin et al, 2004), but also prevents its proteolytic degradation. Hence, the signals that induce expression of ARE-containing mRNAs through inhibition of AMD also cause the accumulation of TTP/BRF1 in the cytoplasm, presumably to be available in the post-induction phase, during which the expression of ARE-containing mRNAs is rapidly turned off.

The ARE-binding protein AUF1 is required for the degradation of a different subset of ARE-containing mRNAs, which might have a role in oncogenesis. D. Morello (Toulouse, France) presented data that translocation-induced ALK kinase fusion proteins, which occur in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, interact with AUF1. This interaction leads to the hyperphosphorylation of AUF1 at tyrosine residues and might contribute to lymphoma formation by the stabilization of ARE-containing mRNAs that are involved in the control of cell proliferation, such as c-Myc and cyclin mRNAs. D. Port (Denver, CO, USA) reported that the phosphorylation of AUF1 at a specific threonine residue in a MAPK consensus site influences both protein oligomerization and its ability to interact with AREs, which might in turn affect the capacity of AUF1 to regulate AMD.

R. Gherzi (Genova, Italy) presented evidence that AMD also has an important role during the differentiation of muscle cells (Briata et al, 2005). In this case, the ARE-binding protein KSRP is a central regulator. Differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes requires activation of p38–MAPK, which phosphorylates KSRP at a specific threonine residue. Phosphorylation of this residue interferes with the ability of KSRP to interact with its target mRNAs. Two target mRNAs, encoding myogenin and the p21 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, thereby become stabilized during the course of differentiation.

NMD: controversial models

It was discovered more than 25 years ago that eukaryotic mRNAs in which the open reading frame is interrupted by a PTC are rapidly degraded by the NMD pathway (Fig 1B). Since then, several NMD factors have been identified, among them the evolutionarily conserved Upf1, Upf2 and Upf3. In addition, components of the exon junction complex (EJC) are involved in NMD in mammals (Baker & Parker, 2004). One key aspect of NMD, however, is still unresolved: What is the basic mechanism by which a termination codon is recognized as being premature? At this meeting, more than one answer to this question was presented.

During the past few years, L. Maquat's group (Rochester, NY, USA) has provided evidence that, in mammals, the first round of translation occurs on mRNAs associated with the cap-binding proteins CBP80/CBP20 that typify nascent transcripts, and that NMD is the consequence of nonsense codon recognition during this ‘pioneer round' of translation (Ishigaki et al, 2001). In line with this idea, Maquat reported on an interaction between CBP80 and Upf1 (Hosoda et al, 2005). Binding of CBP80 to Upf1 promotes the interaction between Upf1 and Upf2 and seems to be necessary for NMD. But is Upf2 always required for NMD? M. Hentze (Heidelberg, Germany) showed that NMD can be activated in the absence of Upf2 by tethering of the EJC components Y14, mago-nashi homologue or eIF4A3 to the mRNA downstream of the termination codon. By contrast, NMD induced by tethering of RNA-binding protein S1 (another EJC component) requires Upf2, suggesting that there are at least two independent routes to assemble NMD-competent mRNPs. The physiological relevance of these findings is supported by the identification of cellular NMD targets that display differential sensitivities to EJC component knockdowns (Gehring et al, 2005). This suggests that structurally distinct EJCs might assemble at different exon junctions, which could explain transcript-dependent differences in NMD efficiency and different subcellular localizations of NMD.

The prevailing NMD model postulates that, in mammals, PTC recognition depends on the presence of an EJC downstream of the terminating ribosome (Maquat, 2004). O. Mühlemann (Berne, Switzerland) challenged this model by showing that in immunoglobulin-μ transcripts, NMD can be induced by PTCs located in the last exon—that is, downstream of the last EJC. Rather than being essential for PTC recognition, the presence of an EJC downstream of the PTC functions as an enhancer of NMD. Instead, PTC recognition in immunoglobulin-μ transcripts seems to depend on the distance between the PTC and a signal in the 3′ UTR, which is reminiscent of NMD in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Amrani et al, 2004; Muhlrad & Parker, 1999), C. elegans (Pulak & Anderson, 1993) and D. melanogaster (Gatfield et al, 2003). This suggests an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of PTC recognition.

A true surprise to the field are the additional functions of NMD factors in processes seemingly unrelated to NMD. Maquat reported that Upf1, by interacting with the RNA-binding protein Staufen1, elicits mRNA decay provided that Staufen1 binds to an mRNA 3′ UTR. Transcripts targeted for Staufen1-mediated mRNA decay exemplify a new type of post-transcriptional gene control (Kim et al, 2005). Recently, the human NMD factors SMG1 and SMG6 have been implicated in DNA repair and telomere maintenance, respectively (Brumbaugh et al, 2004; Reichenbach et al, 2003). As these two proteins are involved in regulating the phosphorylation status of Upf1, J. Lingner's group (Lausanne, Switzerland) investigated whether Upf1 might also have a role in DNA quality control. Lingner provided evidence that Upf1 depletion leads to a cell-cycle arrest in early S-phase and to the accumulation of chromosome aberrations (Azzalin & Lingner, 2006). Moreover, a fraction of Upf1 and SMG1 was found to associate with chromatin, and this association increased significantly in S-phase and with γ-irradiation. These new findings suggest that, apart from its function in NMD, Upf1 has an important role in DNA replication and repair. This is supported further by data showing that Upf1 is an essential factor for the degradation of histone mRNAs at the end of S-phase (Kaygun & Marzluff, 2005). It will be interesting to learn whether these functions of Upf1 are truly independent of NMD, or whether there is a mechanistic link between mRNA quality control, DNA replication and cell-cycle regulation.

Conclusions

This was a superb meeting, with a relaxed, friendly and co-operative atmosphere. The ambience was largely due to the location of the meeting in Arolla, a small Swiss village at an altitude of 2,000 m, surrounded by glaciers and steep mountains. Informal discussions were enhanced by the ‘level' hike high above the valley, the reduced oxygen pressure and a lively dance party to make this a most enjoyable and worthwhile meeting on this rapidly evolving and, more than ever, exciting topic.

Acknowledgments

We thank all scientists who allowed us to mention their work in advance of publication and apologize for the many presentations at the workshop we could not cover here due to space limitations.

References

- Amrani N, Ganesan R, Kervestin S, Mangus DA, Ghosh S, Jacobson A (2004) A faux 3′-UTR promotes aberrant termination and triggers nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature 432: 112–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzalin CM, Lingner J (2006) The human RNA surveillance factor UPF1 is required for S-phase progression and genome stability. Curr Biol (in the press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KE, Parker R (2004) Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: terminating erroneous gene expression. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16: 293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brengues M, Teixeira D, Parker R (2005) Movement of eukaryotic mRNAs between polysomes and cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science 310: 486–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briata P, Forcales SV, Ponassi M, Corte G, Chen CY, Karin M, Puri PL, Gherzi R (2005) p38-dependent phosphorylation of the mRNA decay-promoting factor KSRP controls the stability of select myogenic transcripts. Mol Cell 20: 891–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook M, Tchen CR, Santalucia T, McIlrath J, Arthur JSC, Saklatvala J, Clark AR (2006) Post-translational regulation of tristetraprolin subcellular localization and protein stability by p38 MAPK and ERK pathways. Mol Cell Biol (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh KM, Otterness DM, Geisen C, Oliveira V, Brognard J, Li X, Lejeune F, Tibbetts RS, Maquat LE, Abraham RT (2004) The mRNA surveillance protein hSMG-1 functions in genotoxic stress response pathways in mammalian cells. Mol Cell 14: 585–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrick DM, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ (2004) The tandem CCCH zinc finger protein tristetraprolin and its relevance to cytokine mRNA turnover and arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 6: 248–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller J, Parker R (2005) General translational repression by activators of mRNA decapping. Cell 122: 875–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougot N, Babajko S, Seraphin B (2004) Cytoplasmic foci are sites of mRNA decay in human cells. J Cell Biol 165: 31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JL, Sully G, Clark AR, Saklatvala J (2004) The involvement of AU-rich element-binding proteins in p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway-mediated mRNA stabilisation. Cell Signal 16: 1113–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenger-Gron M, Fillman C, Norrild B, Lykke-Andersen J (2005) Multiple processing body factors and the ARE-binding protein TTP activate mRNA decapping. Mol Cell 20: 905–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara N, Ebert J, Unterholzner L, Lindner D, Izaurralde E, Conti E (2005) SMG7 is a 14-3-3-like adaptor in the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway. Mol Cell 17: 537–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D, Unterholzner L, Ciccarelli FD, Bork P, Izaurralde E (2003) Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in Drosophila: at the intersection of the yeast and mammalian pathways. EMBO J 22: 3960–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring NH, Kunz JB, Neu-Yilik G, Breit S, Viegas MH, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE (2005) Exon-junction complex components specify distinct routes of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay with differential cofactor requirements. Mol Cel 20: 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda N, Kim YK, Lejeune F, Maquat LE (2005) CBP80 promotes interaction of Upf1 with Upf2 during nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in mammalian cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 893–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigaki Y, Li X, Serin G, Maquat LE (2001) Evidence for a pioneer round of mRNA translation: mRNAs subject to nonsense-mediated decay in mammalian cells are bound by CBP80 and CBP20. Cell 106: 607–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaba S, Krueger A, Trice T, Krecic AM, Hinnebusch AG, Anderson J (2004) Nuclear surveillance and degradation of hypomodified initiator tRNAMet in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev 18: 1227–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaygun H, Marzluff WF (2005) Translation termination is involved in histone mRNA degradation when DNA replication is inhibited. Mol Cell Biol 25: 6879–6888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Anderson P (2002) Stress granules: sites of mRNA triage that regulate mRNA stability and translatability. Biochem Soc Trans 30: 963–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Stoecklin G, Ayodele M, Yacono P, Lykke-Andersen J, Fitzler MJ, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Golan DE, Anderson P (2005) Stress granules and processing bodies are dynamically linked sites of mRNP remodeling. J Cell Biol 169: 871–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD, Tenenbaum SA (2002) Eukaryotic mRNPs may represent posttranscriptional operons. Mol Cell 9: 1161–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khabar KS (2005) The AU-rich transcriptome: more than interferons and cytokines, and its role in disease. J Interferon Cytokine Res 25: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, Furic L, Desgroseillers L, Maquat LE (2005) Mammalian Staufen1 recruits Upf1 to specific mRNA 3′UTRs so as to elicit mRNA decay. Cell 120: 195–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCava J, Houseley J, Saveanu C, Petfalski E, Thompson E, Jacquier A, Tollervey D (2005) RNA degradation by the exosome is promoted by a nuclear polyadenylation complex. Cell 121: 713–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidder P, Gutierrez RA, Salome PA, McClung CR, Green PJ (2005) Circadian control of messenger RNA stability. Association with a sequence-specific messenger RNA decay pathway. Plant Physiol 138: 2374–2385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon GJ, Parker R (2005) MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P-bodies. Nat Cell Biol 7: 719–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquat LE (2004) Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlrad D, Parker R (1999) Aberrant mRNAs with extended 3′ UTRs are substrates for rapid degradation by mRNA surveillance. RNA 5: 1299–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbury S, Woollard A (2004) The 5′–3′ exoribonuclease xrn-1 is essential for ventral epithelial enclosure during C. elegans embryogenesis. RNA 10: 59–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Song H (2004) The enzymes and control of eukaryotic mRNA turnover. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Artus CG, Zoller T, Cougot N, Basyuk E, Bertrand E, Filipowicz W (2005) Inhibition of translational initiation by Let-7 microRNA in human cells. Science 309: 1573–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulak R, Anderson P (1993) mRNA surveillance by the Caenorhabditis elegans smg genes. Genes Dev 7: 1885–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenbach P, Hoss M, Azzalin CM, Nabholz M, Bucher P, Lingner J (2003) A human homolog of yeast Est1 associates with telomerase and uncaps chromosome ends when overexpressed. Curr Biol 13: 568–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidlin M, Lu M, Leuenberger SA, Stoecklin G, Mallaun M, Gross B, Gherzi R, Hess D, Hemmings BA, Moroni C (2004) The ARE-dependent mRNA-destabilizing activity of BRF1 is regulated by protein kinase B. EMBO J 23: 4760–4769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth U, Parker R (2003) Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science 300: 805–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin G, Stubbs T, Kedersha N, Wax S, Rigby WF, Blackwell TK, Anderson P (2004) MK2-induced tristetraprolin:14-3-3 complexes prevent stress granule association and ARE-mRNA decay. EMBO J 23: 1313–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin G, Mayo T, Anderson P (2005) ARE-mRNA degradation requires the 5′–3′ decay pathway. EMBO Rep 7: 72–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacova S, Wolf J, Martin G, Blank D, Dettwiler S, Friedlein A, Langen H, Keith G, Keller W (2005) A new yeast poly(A) polymerase complex involved in RNA quality control. PLoS Biol 3: e189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilusz CJ, Wilusz J (2004) Bringing the role of mRNA decay in the control of gene expression into focus. Trends Genet 20: 491–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyers F et al. (2005) Cryptic pol II transcripts are degraded by a nuclear quality control pathway involving a new poly(A) polymerase. Cell 121: 725–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]