Abstract

Hepatocytes are the major epithelial cells of the liver and they display membrane polarity: the sinusoidal membrane representing the basolateral surface, while the bile canalicular membrane is typical of the apical membrane. In polarized HepG2 cells an endosomal organelle, SAC, fulfills a prominent role in the biogenesis of the canalicular membrane, reflected by its ability to sort and redistribute apical and basolateral sphingolipids. Here we show that SAC appears to be a crucial target for a cytokine-induced signal transduction pathway, which stimulates membrane transport exiting from this compartment promoting apical membrane biogenesis. Thus, oncostatin M, an IL-6-type cytokine, stimulates membrane polarity development in HepG2 cells via the gp130 receptor unit, which activates a protein kinase A-dependent and sphingomyelin-marked membrane transport pathway from SAC to the apical membrane. To exert its signal transducing function, gp130 is recruited into detergent-resistant membrane microdomains at the basolateral membrane. These data provide a clue for a molecular mechanism that couples the biogenesis of an apical plasma membrane domain to the regulation of intracellular transport in response to an extracellular, basolaterally localized stimulus.

Keywords: apical plasma membrane/HepG2 cell/oncostatin M/sphingomyelin/subapical compartment

Introduction

Tissue development or organogenesis involves a carefully orchestrated interplay of molecular factors that regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Eventual maturation is reflected by the expression of tissue- and stage-specific genes, and molecular parameters relevant to such a development are gradually being clarified. It has thus been demonstrated that members of the interleukin-6 (IL-6)-related cytokine family, which includes leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), oncostatin M (OSM), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1), IL-11 and IL-6, may function as signal inducers in such events. Thus LIF has been shown to induce differentiation of mesenchyme to epithelium in rat metanephros (Barasch et al., 1999), while OSM induces differentiation of (fetal) hepatocytes, the major epithelial cells of the liver (Yoshimura et al., 1996; Kamiya et al., 1999). In the latter case, OSM has been shown to stimulate progression of hepatic development, evidenced by morphology and the induction of marker genes for the postnatal liver. A unique feature of the IL-6-related cytokine family is that their receptors share the gp130 receptor subunit as a common signal transducer in combination with cytokine-specific subunits. The shared use of the gp130 signal transducer could explain the significantly identical nature of their biological properties.

An important step in the development of epithelia is the establishment of close intercellular membrane interactions (Matsui et al., 2002) and the intracellular molecular machineries mediating these events, which include Rho family proteins, are gradually being revealed. Recently, evidence was provided in a fetal rat hepatocyte system that OSM may also contribute to the regulation of cellular architecture by triggering, in a K-Ras signaling-dependent manner, the localization of E-cadherin, β-catenin and actin at cell–cell junctions (Matsui et al., 2002). These so-called adherens junctions tightly connect adjacent cells and such junctions are part of the multiple modes by which adjacent epithelial cells adhere, and they include desmosomes and tight junctions. Hence, these data may imply that OSM-mediated signaling pathways may also be involved in the regulation of polarity development in adult hepatocytes. As with other epithelial cells, hepatocytes are polarized and have distinct membrane domains, i.e. an apical domain, facing the bile canaliculus, and a basolateral domain, facing adjacent cells and the blood. Accordingly, each domain has its specific protein and lipid composition. Since the polarized phenotype is fundamental for the specialized functions of the epithelial cell, including that of the liver, it is imperative that proteins and lipids are delivered to the correct plasma membrane (PM) domain to achieve and maintain membrane cell polarity.

In mature, polarized HepG2 cells, we recently identified an endosomal organelle, the so-called subapical compartment or SAC, which fulfills a prominent role in the biogenesis of the bile canalicular membrane, displaying the ability to sort and redistribute apical and basolateral lipids and, presumably, proteins (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1998, 1999). Interestingly, a polarity development-dependent pathway, exiting from SAC and related to de novo assembly of the apical membrane, has been identified, which is marked by co-transport of an apical membrane protein, the poly-Ig receptor and the sphingolipid sphingomyelin (SM). This pathway can be triggered upon activation of protein kinase A (PKA), which leads to hyperpolarization (Zegers and Hoekstra, 1997). Intriguingly, intrinsic activation of PKA appears instrumental in activating this apical transport pathway during early development of membrane polarity in cultured HepG2 cells (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 2000), emphasizing the potential physiological significance of this mechanism in polarity development. By contrast, in mature polarized cells, SM exiting from SAC is primarily directed towards the basolateral membrane.

In light of the above considerations, we have addressed the question of whether cytokines of the IL-6 cytokine family, in particular OSM, may play a regulatory role in polarity development of liver cells. In addition, we focused on the issue of whether the SAC-mediated switch in SM trafficking, occurring upon stimulation of polarity development, represented a potential target for a cytokine-induced signal transduction pathway, thereby regulating the biogenesis of the apical PM. If so, this would provide a clue for a molecular mechanism that couples the biogenesis of a PM domain to the regulation of intracellular transport in response to an extracellular stimulus. Our data reveal that OSM stimulates PM polarization of HepG2 hepatoma cells via the gp130 signal transducer, and that this hyperpolarization is associated with an increased membrane flow, marked by SM transport, from the SAC to the apical PM. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the effect of OSM-stimulated polarity development correlates with PKA activity.

Results

Oncostatin M induces hyperpolarization of HepG2 cells

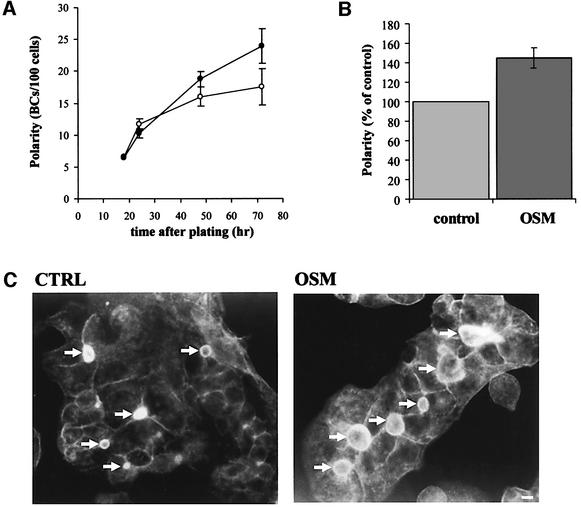

After plating, HepG2 cells express their polarized phenotype in a time-dependent manner, maximal polarity being reached after 72 h (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 2000). The bile canaliculi (BC) in the polarized cells are readily visualized by microscopy, using phalloidin– TRITC as a sensitive stain for the actin filaments, which are abundantly present underneath the apical membrane. By simultaneously staining the cells with the nuclear stain Hoechst 33258, a reliable estimate of cell polarity development can be made by counting the number of BC/cells (Zegers and Hoekstra, 1997). As shown in Figure 1A, in control cells the degree of cell polarity development increases rapidly over the first 24 h after plating and subsequently levels off, reaching an optimal level of polarity in terms of BC/cell ratio after ∼72 h. In the presence of OSM, the level of polarity development over the first 24 h did not differ from that observed for control cells. However, instead of a deflection in development seen for control cells after this time interval, the presence of the cytokine causes an extension of this rapid phase, the level of polarity reaching optimal values after ∼48 h. Intriguingly, a very similar level of BC development is obtained when control cells, displaying an optimal level of polarity development as obtained after 72 h in culture (see also van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 2000), were subsequently treated with OSM for another 4 h (Figure 1B). These data suggest that particularly cells in the progress of cell polarity development are susceptible to OSM-induced stimulation of BC development. Moreover, not only did OSM induce an increase in the number of bile canalicular domains, also the relative surface area of the bile canalicular membrane, relative to that of control cells, increased several-fold, implying that the cytokine’s action resulted in hyperpolarization of the HepG2 cells (Figure 1C).

Fig. 1. Treatment of HepG2 cells with the interleukin OSM induces hyperpolarization. (A) Cells were plated at low density onto ethanol sterilized coverslips in culture medium with (closed circle) or without (open circle) 10 ng/ml rhOSM. After several time intervals the cells were fixed in ethanol and stained with phalloidin–TRITC and the nuclear stain Hoechst 33528. Polarity, expressed as BC/cell ratio, was determined as detailed in Materials and methods. (B) HepG2 cells, grown for 72 h on coverslips, were stimulated with or without OSM for 4 h, and the polarity of the culture was determined as described. (C) Fluorescence micrographs of HepG2 cells grown for 72 h in the presence (right) or absence of rhOSM, fixed and stained with phalloidin–TRITC to stain for actin as described. Note the relative increase in number and surface area of the bile canalicular structures (arrows) in cells treated with OSM. Bar is 5 µm.

OSM-induced hyperpolarization does not affect apical membrane integrity

To investigate whether the enhanced biogenesis of the apical membrane, as accomplished by OSM treatment, was compromised by potential defects of the polarized features of the cells, the localization and functionality of some typical apical proteins was investigated. To this end, we first determined the localization of MDR1, a protein known to be exclusively localized in the apical membrane of both hepatocytes (Kipp and Arias, 2000) and HepG2 cells (Aït Slimane et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 2, also after treatment with OSM, MDR1 localizes exclusively to the apical membrane surface, which indicates that the sorting and transport of MDR1 toward its apical destination is functioning properly, and that the integrity of the apical PM is intact. Consistent with this notion, the localization of the apical t-SNARE syntaxin 3 (Fujita et al., 1998) is also indistinguishable in control and OSM-treated cells (Figure 2). These data would imply that the fence-function of the tight junctional complexes is properly assembled under OSM-induced (hyper)polarity conditions. Indeed, the major protein component of this complex, zona occludens 1 (ZO-1), maintained its proper localization and surrounds the boundary between the apical and (baso)lateral membrane (Figure 2). Moreover, maintenance of the lumenal integrity as a closed intercellular space is revealed by showing the accumulation of Rhodamine 123 into the BC lumen, following loading of the cells with the dye and its subsequent expulsion due to MDR1 pumping activity (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. OSM-induced hyperpolarization does not interfere with the structural and functional integrity of the BC. HepG2 cells were treated with (right) or without (left) OSM for 72 h, fixed and stained for actin with phalloidin–TRITC (A), the tight junction protein ZO-1 (B; red), the apical membrane markers MDR1 (B; green) and Syntaxin 3 (C). To verify the functional integrity following OSM-induced hyperpolarization, HepG2 cells were treated for 72 h with (right) or without (left) the interleukin. The efficiency by which MDR1 removed cell-loaded Rhodamine 123 from treated and non-treated cells, as revealed by pumping of the dye into the BC lumen (D), was then shown as described in Materials and methods. Large arrows mark the bile canalicular (BC) structures, while the small arrows indicate the basolateral membrane of the cells. Bar is 5 µm.

In summary, OSM treatment stimulated polarity development and caused hyperpolarization, without compromising apical membrane integrity and/or its functionality.

Apically directed bulk membrane flow is enhanced by OSM

In previous work we demonstrated that the flow of fluorescently tagged sphingomyelin (C6-NBD-SM) marks an intracellular membrane transport pathway, which closely correlates with polarity development of the HepG2 cells. This bulk membrane transport pathway is stimulated upon activation of PKA, following exogenous addition of dibutyryl cAMP (dBcAMP) (Zegers and Hoekstra, 1997), causing an increase in the number of BC/cells as well as an increase in apical membrane surface area, very reminiscent of the data obtained by OSM stimulation. It was therefore of interest to determine whether activation of OSM-induced (hyper)polarization similarly stimulated the apical membrane-directed bulk transport pathway, marked by C6-NBD-SM. Thus, the effect of OSM on basolateral-to-apical transcytosis was monitored following insertion of the fluorescent SM analog in the basolateral PM of HepG2 cells at 4°C for 30 min. Subsequently, transcytotic SM transport was activated by raising the temperature to 37°C, in the presence and absence of OSM for different time periods. After the indicated time intervals, the cells were cooled to 4°C and residual basolateral SM was then removed by a bovine serum albumin (BSA)-back exchange procedure, and the apical localization was quantified by identifying the percentage of labeled BCs by fluorescence microscopy. The results, depicted in Figure 3, demonstrate that basolateral-to-apical transcytosis of C6-NBD-SM is stimulated in the presence of OSM as a function of time, as revealed by an increased number of C6-NBD-SM labeled BCs under those conditions.

Fig. 3. Basolateral-to-apical transcytosis of C6-NBD-SM is stimulated in OSM-treated cells. HepG2 cells were labeled with 4 µm C6-NBD-SM for 30 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the cells were washed and incubated with or without OSM for another 30 min at 4°C. Transport was triggered in the presence or absence of OSM by incubating the cells at 37°C. After different time intervals cells were cooled to block transport and the number of NBD-positive BCs was determined and expressed as percentage of control.

The data thus indicate that the presence of OSM stimulates apically directed bulk membrane flow, previously shown to be associated with an activation of polarity development in HepG2 cells (Zegers and Hoekstra, 1997).

IL-6 type cytokines induce hyperpolarization of HepG2 cells via the gp130 receptor subunit

The observations that OSM stimulates polarized transport in HepG2 cells raised the question as to the mechanism by which the cytokine propagated its signal. OSM belongs to the functionally and structurally related group of the IL-6 cytokine family. Each type of cytokine of this family is recognized by a specific ligand binding receptor subunit, linked to the common signal transducer gp130 (Taga and Kishimoto, 1997; Heinrich et al., 1998). As a consequence, the members of this family exert overlapping physiological responses. For this reason we tested another cytokine of the IL-6 type cytokine family for its potential capacity to stimulate bile canalicular domain formation in the HepG2 hepatoma cell line. IL-6 proved to be as effective as OSM in stimulating polarity development in HepG2 cells (Figure 4A). By contrast, the non-IL-6 related cytokines IL-1β and IL-4, both known to stimulate HepG2 cells (Gabay et al., 1999), were ineffective and the extent of polarity development in these cases was indistinguishable from that obtained for control cells (Figure 4A). These data thus support the view that the stimulated polarity development is specifically related to IL-6-type cytokines and moreover, that the stimulating effect could be transmitted via the common gp130 signal transducer subunit.

Fig. 4. Multiple members of the IL-6 family stimulate polarity development of HepG2 cells through the gp130 signal transducer. Cells were treated with IL-6 (100 U/ml), OSM (10 ng/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or IL-4 (10 ng/ml) (A), and with the gp130 antagonizing monoclonal antibody AN-H1 (1 µg/ml) or the non-specific basolateral membrane directed antibody CE9 (1 µg/ml) to verify the specificity of signaling through gp130 (B). After 72 h of treatment the cells were fixed and a BC/cell ratio determination was performed as described in Materials and methods.

To investigate this possibility, we determined OSM-mediated polarity development following treatment of the cells with an antagonizing monoclonal antibody against gp130, AN-H1. This antibody is closely related to B-R3 and acts specifically on the level of gp130-mediated signal transduction (Chevalier et al., 1996). After culturing for 72 h in the presence of the AN-H1 antibody, the HepG2 cells not only showed an abolishment of the OSM effect on polarity, but compared to control cells, an even-more depolarized phenotype was obtained, as reflected by a decrease of ∼30% in the BC/cell ratio (Figure 4B). However, this additional decrease can be readily explained by the presence of IL-6-type cytokines in the HepG2 cell culture medium. Treatment of the cells with the non-gp130 related antibody CE-9, but directed against the basolateral surface, had no effect on polarity (Figure 4B), which confirms the specificity of the AN-H1 antibody. These data thus demonstrate that IL-6-related cytokines are capable of stimulating polarity development in HepG2 cells, and that the effect is accomplished via their common gp130 signal transducer.

OSM induces raft association of gp130, which functionally correlates with polarity development

Initiation of OSM signal transduction is caused by binding of the cytokine to its receptor, which induces protein– protein interactions with the common signal transducer gp130, present on the basolateral PM. Since accumulating evidence suggests that lipid microdomains, characterized by their insolubility in certain detergents, may function as signaling platforms (reviewed in Simons and Toomre, 2000), it was of interest to determine whether OSM-induced signaling via gp130 similarly required recruitment of the receptor complex in such microdomains. We therefore extracted cell lysates of control and OSM-treated cells with Triton X-100 in the cold, as described in Materials and methods, and analyzed the pellet and supernatant fractions by western blotting (Figure 5A) or fractionated the detergent extracts by centrifugation to equilibrium on sucrose density gradients (Figure 5B). As shown in Figure 5A, compared with non-stimulated cells, cells stimulated for 30 min with OSM showed a strong enhancement (2–3-fold) in the fraction of the gp130 signal transducer, localized in the Triton X-100 insoluble fraction. Similarly, analysis of the gradient revealed that gp130, following OSM stimulation, was highly enriched, relative to control, in the lighter fractions of the gradient (Figure 5B), indicative of an OSM-induced recruitment of gp130 into insoluble, lipid-enriched domains, thus excluding interference of cytoskeletal interactions. Consistently, after depletion of PM cholesterol with cyclodextrin, OSM treatment of the cells failed to induce significant raft association of gp130 (Figure 5A and C). Accordingly, these data indicate that following OSM stimulation, gp130 is recruited into cholesterol-enriched microdomains at the basolateral surface of HepG2 cells.

Fig. 5. gp130 is recruited into Triton X-100 insoluble microdomains upon OSM stimulation. (A, B and C) Western blots, showing analyses of Triton X-100 extracts from HepG2 cells, that had been cultured for 72 h and treated with or without OSM for 30 min. Triton X-100 extractions were performed as described in Materials and methods. (A) After Triton X-100 extraction, extracts were centrifuged and supernatants (sup; Triton X-100-soluble) and pellets (pel; Triton X-100-insoluble) were analyzed for gp130. gp130 becomes raft-associated after OSM treatment (upper panel), whereas cholesterol depletion, following treatment with cyclodextrin and lovastatin, precludes gp130 raft association (lower panel). The extracts were also analyzed by sucrose gradient floatation (B and C). Triton X-100 insoluble gp130 is found in fractions 4 and 5 corresponding with the boundary of 5 and 35% sucrose and marked by the presence of a control raft protein, Cav-1, as indicated. As a control for the soluble fractions (8–12), actin was used as a marker. Percentages are expressed as percentage of total gp130 present on the blot. (C) Sucrose density floatation of gp130 after Triton X-100 extraction. Fractions 4 and 5, representing the raft fractions and the non-floating fractions present in the 40% sucrose at the bottom of the gradient (fractions 9–12) were pooled. Equal amounts of protein were loaded on the gels. The upper panel shows the western blot for gp130 in control cells and cells treated with OSM; the lower panel shows gp130 in control and OSM-treated cells after PM cholesterol depletion with cyclodextrin, in the presence of lovastatin. (D) PM cholesterol was depleted by incubation with 10 mM cyclodextrin and lovastatin (CD) whereafter cells were incubated with or without OSM for 4 h. After stimulation the cells were fixed and the BC/cell ratio, as a measure of polarity, was determined.

Is gp130 recruitment into rafts directly correlated to the observed OSM-induced hyperpolarity? To address this question, we depleted cholesterol from the PM as above, and determined whether at these conditions OSM treatment of the cells still induced hyperpolarization of the cells, as quantified by determination of the BC/cells ratio. As shown in Figure 5D, relative to control, polarity was reduced, which is consistent with a requirement for gp130 recruitment into rafts in order to allow propagation of the OSM signal, necessary to stimulate polarity development in HepG2 cells.

OSM-induced hyperpolarization is dependent on PKA activity

The consequences of the exposure of HepG2 cells to OSM in terms of hyperpolarization as reflected by an increase in BC/cells, a net increase of the apical membrane surface area and apically directed bulk membrane flow, are remarkably similar to those observed when the cells were treated with dBcAMP. As shown previously (Zegers and Hoekstra, 1997), in the latter case apically directed sphingolipid transport, in both the basolateral-to-apical transcytotic and the biosynthetic trans-Golgi network (TGN)-to-apical transport pathway, was strongly promoted. Evidence was provided that the effect was mediated by an activation of PKA. Moreover, also during early cell polarity development transient activation of intrinsic PKA appeared instrumental in apical BC membrane assembly, causing activation of a vesicular transport pathway from the subapical compartment SAC to the apical PM domain, marked by apical transport of C6-NBD-SM. Reasoning therefore that PKA activity may represent a key regulator in polarity development, we investigated the possibility of whether OSM-induced hyperpolarization of HepG2 cells also relied on PKA activity.

To this end we determined the BC/cell ratio of HepG2 cells after a 72 h incubation with OSM in the absence or presence of 10 µM H89, a specific inhibitor of PKA. Due to inhibition of endogenous PKA following addition of H89 to the culture medium, the BC/cell ratio already decreased to ∼80% of control levels (not shown; compare with van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 2000). Most importantly, OSM addition failed to enhance the BC/cell ratio in the presence of H89 (Figure 6A). These observations imply that inhibition of endogenous PKA abolishes the effects of OSM on polarity development.

Fig. 6. OSM stimulated hyperpolarity is mediated by endogenous PKA activity. (A) HepG2 cells were cultured for 72 h in the presence or absence of OSM (10 ng/ml), with or without the PKA inhibitor H89 (10 µM). After fixation and staining with phalloidin–TRITC and Hoechst 33528, the BC/cell ratio was determined and expressed as percentage of control. (B) PKA activity in HepG2 cells. After culturing HepG2 cells for 3 days, PKA activity was measured using a PepTag Assay specific for PKA (see Materials and methods). Phosphorylation by PKA of the fluorescently labeled peptide substrate alters the net charge of the peptide from +1 to –1. This change allows separation of the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated products on an agarose gel. +, anode; –, cathode; positive (pos) and negative (neg) control (see Materials and methods); 1, non-stimulated cells; 2, cells stimulated with OSM for 30 min; 3, cells stimulated with dBcAMP for 30 min. (C) Immunolocalization of PKAR11 in HepG2 cells, cultured with (right) or without (left) OSM for 72 h. Note the close proximity of the centrioles (arrowheads) in OSM-treated cells to the BC. BCs are marked with arrows. Bar is 5 µm.

Intriguingly, in contrast to dBcAMP, which enhances endogenous PKA activity as revealed by an enhancement in phosphorylation of a PKA-specific fluorescently tagged peptide substrate, such an activation was not immediately apparent following OSM treatment (Figure 6B). Rather, upon microscopic examination of the intracellular distribution of PKA in control and OSM-stimulated cells, we noted a distinct redistribution of PKA following OSM stimulation, showing its recruitment to the centrosomal region of the cell (Figure 6C). Hence, the data suggest that the OSM effect mediated via PKA is more likely to be related to a mobilization to its target site, thus indirectly affecting the efficiency of local PKA activity, than to an overall stimulation of its activity.

OSM and PKA activation redirect SM traffic from SAC towards the BC

Membrane trafficking, departing from the SAC in HepG2 cells, is a primary target site for PKA. Specifically, in optimally polarized cells (72 h) C6-NBD-SM, loaded in the SAC, trafficks to the basolateral membrane domain, whereas a switch in direction to the apical membrane occurs during either early polarity development (18 h) or upon exogenous activation of PKA by dBcAMP. As noted, the latter pathway is inhibited upon additon of the specific PKA inhibitor H89.

Since previous work revealed that PKA activation redirects outbound trafficking of SM from SAC from a basolateral to an apical direction upon hyperpolarization, it was of interest to next determine whether the effect of OSM similarly affected the SM-marked outbound trafficking pathway from SAC to apical membrane, typically reflecting the pathway that promotes BC biogenesis. For this purpose we loaded the SAC with C6-NBD-SM, using a procedure as depicted in Figure 7A. After a preincubation with OSM or dBcAMP at 18°C, transport from the SAC was activated by a subsequent incubation at 37°C in the presence of BSA-back exchange medium to retrieve basolateral arriving NBD-lipid and to prevent lipid re-entry into the cells (step 5, Figure 7A). In control cells, C6-NBD-SM is transported from the SAC out of the bile canalicular pole (BCP), which comprises the pool of lipid present in SAC and/or BC, following a chase of 20 min (Figure 7B and C). This is consistent with its preferential basolateral localization, as described before (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1998). In cells treated with dBcAMP, i.e. under conditions of hyperpolarization, C6-NBD-SM remains at the BCP during the chase time (Figure 7B, closed circle), and is redirected towards the bile canaliculus, as reflected by a strong increase of BC-associated lipid (Figure 7C, dBcAMP). Interestingly, the overall picture obtained for cells treated with OSM appeared very similar as that obtained for dBcAMP-treated cells, implying that the lipid prefers an apical localization (Figure 7B, open circles) and redistributes between SAC and BC (Figure 7C, OSM). Taken together, these data suggest that the SAC-mediated redistribution of SM is a crucial target for the OSM-induced signal transduction pathway, which promotes the biogenesis of the apical PM.

Fig. 7. OSM and dBcAMP redirect SM traffic from SAC towards the BC. (A) The experimental procedure to load C6-NBD-SM into the SAC. At 37°C, cells are labeled and with the fluorescent lipid analog (1), followed by its removal from the basolateral membrane by back-exchange (2). By a subsequent incubation at 18°C, the lipid, present in intracellular transport vesicles and in the bile canalicular membrane, is chased into SAC (3). Residual lipid at the BC is finally ‘depleted’ by quenching with sodium dithionite (4) (see also Materials and methods). (B) After having the lipid accumulated in SAC, control (closed squares) and cells pretreated with with dBcAMP (1 mM; closed circle) or OSM (10 ng/ml; open circle) were then chased for 20 min at 37°C. Cells had been pretreated with the corresponding compound after step 4 (panel A) for 30 min at 4°C. Note that while in control cells, C6-NBD-SM disappears from the BCP area (panel A, 4), the lipid remains in this region following treatment with either dBcAMP or OSM. In (C) the fractional distribution of C6-NBD-SM, located in the BCP region as determined in panel B, in CTRL, OSM or dBcAMP-treated cells, after a 20 min chase from the SAC, is indicated. Whereas the lipid redistributes over BC and SAC (compare with 4 in panel A) in the treated cells (dBcAMP; OSM), indicative of lipid trafficking in apical direction, no significant increase in labeled lipid is seen at the BC in control cells (CTRL). The latter is consistent with its departure from the BCP region towards the basolateral membrane.

Discussion

The IL-6 related family of cytokines are candidate regulators of differentiation and development (Bruce et al., 1992; Barasch et al., 1999) and one of its members, OSM, appears to play a prominent role in the development of fetal hepatocytes, as reflected by its ability to induce morphological changes, intercellular E-cadherin and catenin-based adherens junctions, differentiation markers and functional maturation (Kamiya et al., 1999; Matsui et al., 2002). The present work adds an entirely novel functional property to the signal-transducing capacity expressed by at least two of its family members, i.e. OSM and IL-6, but not the non-related IL-1β and IL-4: strong promotion of polarity development in cultures of (adult) human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Specifically, the data reveal for the first time a cytokine-induced transduction pathway, originating at the basolateral membrane, which stimulates the biogenesis of the apical PM, thus providing a clue for a molecular mechanism that couples the biogenesis of a PM domain to the regulation of intracellular membrane transport in response to an extracellular stimulus. OSM propagates this signal via the common gp130 subunit of the interleukin receptor, as reflected by abrogation of the polarity stimulating signal following treatment with a gp130-specific antibody. Interestingly, a prerequisite for gp130-mediated signaling is its recruitment into detergent-insoluble sphingolipid/cholesterol- enriched rafts upon binding of OSM, as hyperpolarization is abolished upon removal of PM cholesterol. A potential target of the likely raft-mediated gp130 signaling is the subapical compartment SAC, instrumental in the biogenesis and maintenance of the bile canalicular membrane (van IJzendoorn et al., 2000; Maier et al., 2002), since a specific apical membrane-directed vesicular transport pathway, departing from SAC, marked by the fluorescent sphingolipid analog C6-NBD-SM, becomes activated. The inhibition of this transport pathway by H89, a specific inhibitor of PKA, previously shown to inhibit dBcAMP-induced hyperpolarization in a similar manner (Zegers and Hoekstra, 1997; van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 2000), strongly implicates PKA as a mediator in the OSM-promoted signal transduction pathway that promotes polarity development in HepG2 cells. Our preliminary observations (Figure 6C) suggest that rather than a stimulation of overall PKA activity, as noted for the effect of dBcAMP on polarity development, specific recruitment of PKA to its target site in the centrosomal region of the cells may be instrumental in the effect, accomplished by OSM. Interestingly, the SAC is localized in this region of the cell (van IJzendoorn et al., 2000). However, at present neither molecular factors nor the mechanism that links OSM activity and PKA activation are known, and await further investigation.

Previous investigations clarified a role for OSM in the differentiation of fetal mice hepatocytes (Kamiya et al., 1999), and their tight interaction via the establishment of E-cadherin-based adherence junctions (Matsui et al., 2002). By contrast, the latter authors excluded involvement of OSM signaling in the formation of tight junctions, which constitute the fence-forming structures between apical (bile canalicular) and basolateral domain. In line with these observations, our data suggest that OSM does not induce polarity development as such. Rather, during early development of polarity, the cells gradually acquire cytokine susceptibility and only after some 36 h (Figure 1), the strong promoting effect of OSM, as reflected by an increase in number and surface area of functional BCs, is apparent. This issue is further emphasized by the notion that the OSM signaling effect becomes readily apparent, when the cells are ‘primed’, as hyperpolarization is seen within 4h when more advanced polarized cells are exposed to the cytokine (Figure 1B). These observations could imply that the expression of the IL-6R is developmentally regulated, which is currently unknown. Taking this one step further, it is then tempting to propose that at physiological conditions an OSM stimulus might accelerate the re-establishment of the polarized phenotype, after polarity has been compromised by toxic or disease-related mechanisms.

An intriguing aspect of the stimulatory consequences of OSM represents the reversal of SM trafficking from the SAC to apical instead of basolateral membrane, as observed under control conditions. Not surprisingly, the effect is very reminiscent of previous observations on a similar consequence in SM trafficking, following PKA activation, a step that also appears to be involved in OSM-mediated (hyper-)polarization. Evidently, this transport pathway relies on vesicular transport, carrying both C6-NBD-SM and the apical protein pIgR to the apical membrane (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1999). How ever, the question arises, whether apart from marking a vesicular membrane transport pathway, transport of SM along this pathway might also serve a functional purpose, taking into account its prominent role in the assembly (with cholesterol) of rafts (Simons and Ikonen, 1997; Hoekstra and van IJzendoorn, 2000). In this context, it has been reported that during early development of neurons, the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked protein Thy-1 is randomly transported to dendrite and axonal membranes. When development progresses and concomitantly the biogenesis of rafts is seen to occur, the protein becomes exclusively targeted to the axonal membrane domain (Ledesma et al., 1999). Interestingly, by increasing intracellular levels of SM, following loading of the cells with e.g. C6-NBD-SM, raft formation and sorting were also induced in early developing neurons, causing Thy-1 to be transported to the axonal (or apical) membrane domain. It is possible therefore that the OSM signal-induced reprogramming in the direction of SM transport may serve a very similar purpose. Essentially, these data also re-emphasize the sorting capacity of the SAC in polarity development. We previously showed that galactosylceramide is sorted from SAC in a basolateral-directed pathway, whereas its C2-epimer glucosylceramide enters an apical recycling pathway (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1998).

It is finally of relevance to consider as to whether OSM signaling exclusively affects polarity development in adult HepG2 cells by a gp130-mediated downstream recruitment of PKA activity, which leads to a defined redistribution of SAC-derived membrane transport. E-cadherin is known to directly affect the epithelial cell phenotype by organizing cells in a structural and functional polarized cell (Nathke et al., 1993). Also LIF, another IL-6-type cytokine, is known to induce expression of E-cadherin mRNA in rat metanephric mesenchyme, which is a characteristic for the conversion of mesenchyme to epithelium (Barasch et al., 1999). In HepG2 cells, the increased expression of E-cadherin mRNA was not observed when stimulated by OSM (results not shown), which implies that the increased polarity after OSM stimulation is not mediated by an increment of E-cadherin mRNA levels, thereby causing an enhanced cell–cell contact. However, it cannot be excluded that E-cadherin can form more pronounced interactions with the membrane cytoskeleton, providing a spatial cue to organize PM polarity. Moreover, very recently it was reported (Matsui et al., 2002) that OSM may induce adherence junctions between fetal hepatocytes by altering the subcellular localization of junction-forming components like E-cadherin and catenins. It is therefore possible that through such enhanced cell–cell contacts, signal pathways are activated or promoted which, for example, trigger an enhanced rate of apical exocytosis (Vega-Salas et al., 1988), in which cAMP may be involved as second messenger. In this context it is interesting to note that Brignoni et al. (1995) have shown that cAMP serves as a second messenger in the constitutive pathway between TGN and apical membrane, whereas basolateral transport remains unaffected in such conditions. Evidently, it is very likely that polarity development is regulated by a set of mechanisms, probably dictated by conditional demands. Apparently, cell–cell contact, signaling via cAMP, and intrinsic responses of intracellular transport are closely connected to such developments. A novel mechanism has been described in this work, relying on the activation of gp130 via OSM or IL-6, which induces an increased apical membrane flow, as reflected by SM transport, leading to an increased BC/cell ratio together with an enlargement of the bile canalicular surface area. The fact that a signal, triggered at the basolateral membrane, culminates in such an evident and sensitive apical response, now paves the way to defining at the molecular level the intracellular mechanism that communicates this transcellular effect.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HepG2 cells were grown in DMEM with 4500 mg of glucose per liter, containing 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. Media were changed every other day. Cells were trypsinized after reaching confluency. For experiments, cells were plated at low density onto ethanol-sterilized coverslips and analyzed 3 days after plating.

Determination of HepG2 cell polarity

Accurate estimation of the degree of HepG2 polarity was performed as described elsewhere (Zegers and Hoekstra, 1997; van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 2000). Briefly, the cells were fixed with –20°C ethanol for 10 s, rehydrated in HBSS, and subsequently incubated with a mixture of TRITC-labeled phalloidin (100 ng/ml) and the nuclear stain Hoechst 33528 (5 ng/ml) at room temperature for 30 min. The cells were then washed and the number of bile canaliculi (BC; identified by the presence of dense F-actin staining around the BC) per 100 cells (identified by fluorescently labeled nuclei) was determined and expressed as the ratio [BC/100 cells]. Ten fields (each containing >50 cells) per coverslip (at least two coverslips per condition were studied) were analyzed. Cells were examined using an epifluorescence microscope (Provis AX70, Olympus corp., New Hyde Park, NY).

Cytokine treatment and inhibition of gp130 by a monoclonal antibody

HepG2 cells, plated on glass coverslips, were treated with cytokines for 4 or 72 h, as indicated. IL-6 (kindly provided by Dr Lutz Graeve, Stuttgart, Germany) was used at a concentration of 100 U/ml and recombinant human oncostatin M (rhOSM) (Cell Concepts GmbH, Umkirch, Germany) at a concentration of 10 ng/ml.

To inhibit gp130 signal transduction, HepG2 cells were plated onto glass coverslips and incubated with 1 µg/ml of the gp130 antagonizing antibody AN-H1 (kindly provided by Dr Hugues Gascan, Angers, France) in cell culture medium. As non-gp130 related antibody we used 1 µg/ml CE9 (kindly provided by Dr Ann Hubbard, Baltimore, USA). After 72 h the ratio of BC per number of cells was determined.

Immunostaining of HepG2 cells

HepG2 cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, washed and permeabilized for 10 min with methanol at –20°C. After blocking with 1% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline the cells were incubated with primary antibody for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Next, the cells were washed and incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes) for 45 min at room temperature. The coverslips were mounted and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP2; Germany).

Preparation of detergent insoluble fractions

HepG2 cells, cultured for 72 h, were treated with β-methyl-cyclodextrin (10 mM) and lovastatin (1 µg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C to remove cholesterol. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with OSM or buffer for 30 min, cooled and subjected to a Triton X-100 extraction at 4°C, as described by Aït Slimane et al. (2003). Briefly, cells were scraped in 0.5 ml TNE (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and a mixture of protease inhibitors), containing 1% (final concentration) Triton X-100, and incubated for 30 min on ice. Insoluble components were spun down and the supernatants (containing Triton X-100 soluble proteins) were collected in a new tube. The pellets were suspended in solubilization buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.8, 5 mM EDTA and 1% SDS) and homogenized. After TCA precipitation, soluble and insoluble fractions were processed for SDS–PAGE, western blotting, applying an enhanced chemi-illuminescence western blotting kit (ECL, Amersham). To analyze detergent insoluble proteins by floatation in a sucrose gradient, a Triton X-100 extraction was performed as described above. Thereafter the extract was brought to 40% sucrose in a final volume of 4 ml and placed at the bottom of a 5–35% sucrose gradient as described by Aït Slimane et al. (2003). Gradients were centrifuged for 20 h at 38 000 r.p.m. at 4°C in a Beckman SW41 rotor. After centrifugation, 1 ml fractions were collected from the top to the bottom. Detergent insoluble fractions were found at the boundary between 5 and 35% sucrose, corresponding to fractions 4 and 5 of the gradient, as revealed by Caveolin-1, which was used as a specific marker for the raft fractions. Actin was used as a marker for the soluble fractions (8–12). After trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation, SDS–PAGE and western blotting, proteins were visualized by ECL (Amersham).

Determination of PKA activity

HepG2 cells, cultured for 72 h, were stimulated for 30 min with OSM (10 ng/ml) or dBcAMP (1 mM). Subsequently, the cells were washed in ice-cold HBSS and kept on ice. Thereafter, the cells were harvested by scraping with a rubber policeman in extraction buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA and a cocktail of protease inhibitors) and homogenized by sonication for 30 s. From this cell extract the protein content was determined, and 10 µg of protein was used in the PepTag Assay for non-radioactive determination of PKA activity (Promega Corporation, USA). The assay was carried out according the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, the assay is based on the use of a fluorescent peptide substrate, specific for PKA. Phosphorylation by PKA of the PepTag peptide alters the net charge from +1 to –1. This change in charge of the substrate allows the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of the substrate to be separated on an agarose gel (0.8% agarose in Tris–HCl pH 8,0). The phosphorylated product migrates towards the negative electrode (cathode), while the non-phosphorylated product migrates towards the positive electrode (anode). The negative control lacks PKA enzyme and contains only buffer, while the positive control contains the PKA supplied with the kit.

Synthesis of C6-NBD-sphingomyelin

C6-NBD-SM was synthesized from C6- nitro-benzoxa-diazole (C6-NBD) and sphingosylphosphorylcholine as described elsewhere (Kishimoto, 1975; Babia et al., 1994). The C6-NBD-SM was stored at –20°C and routinely checked for purity.

Transcytosis of sphingolipids

HepG2 cells were washed three times in HBSS and preincubated for 30 min at 37°C with/without rhOSM (10 ng/ml). After the preincubation, the cells were cooled to 4°C by washing with ice-cold HBSS. Subsequently, the basolateral PM was labeled with 4 µM C6-NBD-SM for 30 min at 4°C with or without rhOSM. In all further incubations rhOSM was included. The cells were then washed and transcytosis was allowed to occur at 37°C for different time periods. To terminate transport, the cells were cooled by washing three times with ice-cold HBSS, and lipid remaining in the outer leaflet of the basolateral membrane was removed by a back-exchange procedure. To this end the cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with 5% BSA in HBSS, followed by washing with ice-cold HBSS. This procedure was repeated once.

Analysis of transport of C6-NBD-sphingolipids from the SAC

In order to study the trafficking of the fluorescent SM analog from the SAC, SAC were preloaded with the lipid as described elsewhere (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1998, 1999). In short, cells were labeled with 4 µM C6-NBD-SM at 37°C to allow internalization from the basolateral surface and subsequent transcytosis to the apical, bile canalicular PM domain (BC). After 30 min of incubation, lipid analog still residing at the basolateral domain was depleted by a back exchange procedure at 4°C (2 × 30 min incubation in HBSS + 5% w/v BSA; compare with van IJzendoorn et al., 1997), and BC-associated lipid analog was chased into the SAC at 18°C for 1 h in back exchange medium. Then, the NBD-fluorescence at the exoplasmic BC leaflet was abolished using sodium dithionite at 4°C, leaving the vast majority of the intracellular SM analog in the SAC (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1998, 2000). After removal of dithionite by washing, transport from the SAC was examined by incubating in back exchange medium at 37°C.

In order to quantitate transport of the lipid analog to and from the BC, the percentage of NBD-positive BC was determined as described elsewhere (van IJzendoorn et al., 1997; van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1998). Briefly, BC were first identified by phase contrast illumination, and then categorized as NBD-positive or NBD-negative under epifluorescence illumination. Note that a BC is categorized as fluorescently labeled, i.e. NBD-positive, when microvilli-like structures, characteristic of the BC, can be detected that are seemingly fluorescent in the wake of the fluorescence derived from the lipid analog, present in the apical membrane (van IJzendoorn et al., 1997). Such microvilli-like structures are typically and readily observed upon gradual photobleaching of the BC-associated NBD fluorescence.

Distinct pools of fluorescence are thus discerned at the apical pole of the cells, present in vesicular structures adjacent to BC, which are defined as subapical compartments (SAC, compare with van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1998). Together, BC and SAC constitute the BCP in HepG2 cells (see Figure 7). Therefore, within the BCP region the localization of the fluorescent lipid analog will be defined as being derived from the BC, the SAC or both. This also provides a means to describe the movement of the lipid within or out of this region in the cell (van IJzendoorn and Hoekstra, 1999). Thus, after loading the SAC with lipid analog and allowing its transport to take place as described above, the direction of movement of the lipid from or within the BCP region is determined after a given time, by establishing the distribution of the NBD-labeled lipid over the various compartments (BC, SAC or both) that constitute the BCP, relative to the labeling (i.e. primarily SAC), prior to starting the chase (t = 0). For this kind of analysis, at least 50 BCP per coverslip were analyzed. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of at least four independent experiments, carried out in duplicate and Student’s t-tests were carried out to determine the statistical significance of the data. A summary of the procedure is illustrated in Figure 7A.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We kindly thank Professor Dr Lutz Graeve (Universität Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany) for helpful discussions and providing us with IL-6. Furthermore, we thank Dr Hugues Gascan (CHRU Angers, Angers, France) for kindly providing us with AN-H1 and Dr Ann Hubbard (Baltimore, USA) for the kind gift of the CE-9 antibody.

References

- Aït Slimane T., Trugnan,G., van IJzendorn,S.C.D. and Hoekstra,D. (2003) Raft-mediated trafficking of apical resident proteins occurs in both direct and transcytotic pathways in polarized hepatic cells: role of distinct lipid microdomains. Mol. Biol. Cell,in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babia T., Kok,J.W. and Hoekstra,D. (1994) The use of fluorescent lipid analogues to study endocytosis of glycosphingolipids. In Greenstein,B. (ed.), Receptor Research Methods. Harward Academic Publishers, London, UK, pp. 155–174.

- Barasch J. et al. (1999) Mesenchymal to epithelial conversion in rat metanephros is induced by LIF. Cell, 99, 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignoni M., Pignataro,O.P., Rodriguez,M.L., Alvarez,A., Vega-Salas,D.E., Rodriguez-Boulan,E. and Salas,P.J. (1995) Cyclic AMP modulates the rate of ‘constitutive’ exocytosis of apical membrane proteins in Madin–Darby canine kidney cells. J. Cell Sci., 108, 1931–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce A.G., Hoggatt,I.H. and Rose,T.M. (1992) Oncostatin M is a differentiation factor for myeloid leukemia cells. J. Immunol., 149, 1271–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier S., Fourcin,M., Robledo,O., Wijdenes,J., Pouplard-Barthelaix,A. and Gascan,H. (1996) Interleukin-6 family of cytokines induced activation of different functional sites expressed by gp130 transducing protein. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 14764–14772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H., Tuma,P.L., Finnegan,C.M., Locco,L. and Hubbard,A.L. (1998) Endogenous syntaxins 2, 3 and 4 exhibit distinct but overlapping patterns of expression at the hepatocyte plasma membrane. Biochem. J., 329, 527–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay C., Porter,B., Guenette,D., Billir,B. and Arend,W.P. (1999) Interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 enhance the effect of IL-1beta on production of IL-1 receptor antagonist by human primary hepatocytes and hepatoma HepG2 cells: differential effect on C-reactive protein production. Blood, 93, 1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich P.C., Behrmann,I., Muller-Newen,G., Schaper,F. and Graeve,L. (1998) Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem. J., 334, 297–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra D. and van IJzendoorn,S.C.D. (2000) Lipid trafficking and sorting: how cholesterol is filling gaps. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A. et al. (1999) Fetal liver development requires a paracrine action of oncostatin M through the gp130 signal transducer. EMBO J., 18, 2127–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipp H. and Arias,I.M. (2000) Newly synthesized canalicular ABC transporters are directly targeted from the Golgi to the hepatocyte apical domain in rat liver. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 15917–15925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto Y. (1975) A facile synthesis of ceramides. Chem. Phys. Lipids, 15, 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma M.D., Brugger,B., Bunning,C., Wieland,F.T. and Dotti,C.G. (1999) Maturation of the axonal plasma membrane requires upregulation of sphingomyelin synthesis and formation of protein–lipid complexes. EMBO J., 18, 1761–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier O., Aït Slimane,T. and Hoekstra,D. (2001) Membrane domains and polarized trafficking of sphingolipids. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol., 12, 149–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Kinoshita,T., Morikamwa,Y., Tohya,K., Katsuki,M., Ito,Y., Kamiya,A. and Miyajima,A. (2002) K-Ras mediates cytokine-induced formation of E-cadherin-based adherens junctions during liver development. EMBO J., 21, 1021–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathke I.S., Hinck,L.E. and Nelson,W.J. (1993) Epithelial cell adhesion and development of cell surface polarity: possible mechanisms for modulation of cadherin function, organization and distribution. J. Cell Sci. Suppl., 17, 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K. and Ikonen,E. (1997) Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature, 387, 569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K. and Toomre,D. (2000) Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 1, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taga T. and Kishimoto,T. (1997) Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 15, 797–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanIJzendoorn S.C.D. and Hoekstra,D. (1998) (Glyco)sphingolipids are sorted in sub-apical compartments in HepG2 cells: a role for non-Golgi-related intracellular sites in the polarized distribution of (glyco)sphingolipids. J. Cell Biol., 142, 683–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanIJzendoorn S.C.D. and Hoekstra,D. (1999) Polarized sphingolipid transport from the subapical compartment: evidence for distinct sphingolipid domains. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 3449–3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanIJzendoorn S.C.D. and Hoekstra,D. (2000) Polarized sphingolipid transport from the subapical compartment changes during cell polarity development. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanIJzendoorn S.C.D., Zegers,M.M.P., Kok,J.W. and Hoekstra,D. (1997) Segregation of glucosylceramide and sphingomyelin occurs in the apical to basolateral transcytotic route in HepG2 cells. J. Cell Biol., 137, 347–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanIJzendoorn S.C.D., Maier,O., van der Wouden,J.M. and Hoekstra,D. (2000) The subapical compartment and its role in intracellular trafficking and cell polarity. J. Cell Physiol., 184, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Salas D.E., Salas,P.J. and Rodriguez-Boulan,E. (1988) Exocytosis of vacuolar apical compartment (VAC): a cell–cell contact controlled mechanism for the establishment of the apical plasma membrane domain in epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol., 107, 1717–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura A., Ichihara,M., Kinjyo,I., Moriyama,M., Copeland,N.G., Gilbert,D.J., Jenkins,N.A., Hara,T. and Miyajima,A. (1996) Mouse oncostatin M: an immediate early gene induced by multiple cytokines through the JAK–STAT5 pathway. EMBO J., 15, 1055–1063. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegers M.M.P. and Hoekstra,D. (1997) Sphingolipid transport to the apical plasma membrane domain in human hepatoma cells is controlled by PKC and PKA activity: a correlation with cell polarity in HepG2 cells. J. Cell Biol., 138, 307–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]