Abstract

Hantaan virus, the etiological agent of Korean hemorrhagic fever, is transmitted to humans from persistently infected mice (Apodemus agrarius), which serve as the primary reservoir. Here we demonstrate that several strains of adult Mus musculus domesticus (C57BL/6, BALB/c, AKR/J, and SJL/J) were susceptible to Hantaan virus infection when infected intraperitoneally. First clinical signs were loss of weight, ruffled fur, and reduced activity, which were followed by neurological symptoms, such as paralyses and convulsions. Within 2 days of disease onset, the animals died of acute encephalitis. PCR analysis indicated a systemic infection with viral RNA present in all major organs. Immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization analyses of postmortem material detected viral antigen and RNA in the central nervous system (predominantly brain), liver, and spleen. In the central nervous system, viral antigen and RNA colocalized with perivascular infiltrations, the predominant pathological finding. To investigate the involvement of the interferon system in Hantaan virus pathogenesis, we infected alpha/beta interferon receptor knockout mice. These animals were more susceptible to Hantaan virus infection, indicating an important role of interferon-induced antiviral defense mechanisms in Hantaan virus pathogenesis. The present model may help to overcome shortcomings in the development of therapeutic and prophylactic measurements against hantavirus infections.

The genus Hantavirus is one of five genera in the family Bunyaviridae. Hantaviruses possess a tripartite, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome with segments designated large (L), medium (M), and small (S) (2, 15, 31). In contrast to other bunyaviruses, hantaviruses are rodent-borne human pathogens that persistently infect their rodent reservoirs without causing obvious clinical signs of illness. Infected rodents shed the virus in urine, saliva, and feces, and transmission to humans normally occurs through the aerosol route when small-particle aerosols of contaminated excreta are inhaled. Therefore, the worldwide appearance of human hantavirus disease is primarily determined by the geographic distribution of the rodent reservoirs of the different hantaviruses (5, 30, 32).

Two clinical syndromes are currently known to be associated with hantavirus infections in humans: hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS). These can be further distinguished by clinical symptoms into severe, moderate, and mild HFRS, classical HPS, and a renal variant of HPS (5, 27, 30). HFRS especially continues to cause significant numbers of human illnesses in Asia and Europe, with approximately 100,000 cases per year (16, 22). HFRS lethality ranges from <1% for Puumala virus (PUUV) infections to approximately 5 to 15% for Hantaan virus (HTNV) infections. The cardinal manifestations of HFRS are fever, hemorrhages, and renal impairment. Severe HFRS, caused by HTNV, Dobrava virus, and sometimes Seoul virus, shows several phases (febrile, hypotensive, oliguric, polyuric, and convalescent) with variable lengths and transitions which are not always present in moderate or mild cases. Important laboratory findings are a rise in serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, thrombocytopenia, proteinuria, and changes in serum electrolytes (5, 27).

Hantaviruses primarily affect blood vessels and lead to variable degrees of generalized capillary dilatation and edema. Viral antigens are found within capillary endothelium of various tissues. Despite the extensive accumulation of viral antigens, there is little ultrastructural evidence of a cytopathic effect in endothelial cells. A hallmark of pathogenesis is increased vascular permeability that seems to be due to endothelial cell dysfunction. By activating complement and by triggering mediator release from platelets and immune effector cells, immune complexes may be involved in vascular injury. Thus, many data are consistent with the hypothesis that hantavirus-induced diseases are due to immunologically mediated capillary leakage in target organs, which differ for HFRS and HPS. The systemic manifestation of capillary dysfunction leads to hypotension and shock, which may be influenced by additional factors, such as virus distribution and virus-induced release of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators. The onset of disease coincides with the appearance of a specific immune response, and immune complexes can be detected in HFRS patients (5, 17, 22, 28, 41).

Hantavirus research has long been hampered by the lack of suitable animal models. However, cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) have been successfully used to mimic nephropathia epidemica, a mild form of HFRS caused by PUUV (8, 19). Laboratory mice (Mus musculus) and rats (Rattus norvegicus) have been used to study hantavirus pathogenicity, but lethal disease could be induced only in newborn or immunodeficient animals (13, 18, 21, 24, 39, 40). Most recently, an HPS disease model with Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) was reported for Andes virus (ANDV), one of the South American hantaviruses (12). This exciting model, which so far works only for ANDV, will be of great use for the development of vaccine candidates and antiviral substances. However, it is less suitable for the characterization of host genetic factors involved in the pathogenesis of hantavirus infections due to the lack of proper genetic and immunological tools for studies with hamsters.

Here we report that HTNV infection is lethal for several inbred strains of M. musculus domesticus. Knockout mice lacking a functional receptor for alpha/beta interferon (IFN-α/β) (25) are even more susceptible to the infection than wild-type mice, indicating an important role of IFN-induced antiviral defense mechanisms in HTNV pathogenesis. Although clinical symptoms in HTNV-infected mice differ from those of HFRS in humans, the mouse model will be helpful for studying hantavirus pathogenesis and genetics. Furthermore, it will be useful for developing vaccines against HFRS.

(Dominic Wichmann performed this work in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. degree from Philipps-Universität, Marburg, Germany.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL/6, BALB/C, AKR/J, and SJL/J mice were purchased from Charles River, Sülzfeld, Germany. Knockout mice lacking a functional receptor for IFN-α/β (IFNAR-1−/− mice) (25) were bred locally. All experiments with live animals were performed under the guidelines of local laws.

Viruses and cells.

Strain 76-118 of HTNV was used for all infections. Virus stocks were grown in Vero E6 cells (ATCC 1887) (two passages) and determined to yield titers of 2 × 106 PFU. Two recombinant vaccinia viruses were used for the protection experiments: a virus expressing the HTNV glycoprotein precursor (VVHTNV/GPC) (23) and a virus expressing the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase (designated here VVT7) (kindly provided by B. Moss, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.). To exclude virus stock contamination, blood samples (200 μl) from three VVHTNV/GPC-vaccinated and HTNV-challenged C57BL/6 mice were taken 21 days postchallenge. The samples tested positive for hantaviruses (HTNV) but negative for other common mouse pathogens in routine serological assays performed by Harlan Winkelmann (Borchen, Germany).

Animal infection and preparation of samples.

Animals either were transferred to HEPA filter isolator units (E. E. Roberts Isolators, Wistanswick, United Kingdom) located in a biosafety level 2 (BSL2) animal facility (Institute of Virology, Marburg, Germany) or were housed in a BSL4 laboratory (Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada). Adult female mice were infected intraperitoneally with HTNV and examined for clinical symptoms twice daily. Moribund animals were euthanized, and parts of the major organs (liver, kidneys, spleen, lungs, and brain) were sampled for further analyses. For histological, immunohistochemical, and in situ hybridization analyses, organs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 days. For reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, organ material was immediately placed into guanidinium isothyocyanate buffer. After proper inactivation, samples were removed from either the isolator units or the BSL4 laboratory by using standard operating protocols.

Histological analysis.

Organ samples were embedded in blocks of paraffin and cut with a microtome into 5-μm sections. The sections were subsequently mounted onto glass slides and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE), periodic acid-Schiff, and Trichrome stains.

Immunohistochemical analysis.

Paraffin-embedded sections (see above) were incubated with xylol to remove the paraffin, rehydrated by using decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100, 95, 80, and 70% for 5 min each), and incubated for 30 min with rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Dako, Hamburg, Germany) to block endogenous mouse IgG. After extensive phosphate-buffered saline washes, antigen detection was performed by using anti-HTNV polyclonal mouse IgG followed by rabbit anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Dako); subsequent staining was done with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Dako). Anti-HTNV polyclonal mouse IgG was obtained from HTNV-infected C57BL/6 mice.

In situ hybridization.

A fragment of 350 nucleotides from the S segment (positions 37 to 1345) of strain 76-118 of HTNV was amplified and cloned into plasmid pCI (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). 32P-labeled in vitro runoff transcripts were produced by using an SP6/T7 transcription kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and purified by using Nuc Trap probe purification columns (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). Hybridization was performed as described previously (3). Briefly, the sections were deparaffinized with xylol, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, and treated with 10% hydrochloric acid and 10 μg of proteinase K/ml (37°C for 20 min). Subsequently, the sections were hybridized with the radiolabeled probe, washed, and dehydrated by using increasing ethanol concentrations (50, 70, 80, 90, and 100% for 5 min each). The tissue sections were dipped in NTB2 photoemulsion (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) and stored in the dark. After 7 days, the photoemulsion was developed, and the sections were counterstained with HE and examined by bright- and dark-field microscopy with an Axiolab microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany).

RT-PCR.

RNA was extracted by using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and RT-PCR was performed by using a Titan one-tube RT-PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim) and a Perkin-Elmer model 2400 thermocycler. The RT reaction was performed at 50°C for 30 s and was followed by 40 amplification cycles (94°C for 30 s and 68°C for 90 s). The following L segment-specific oligonucleotides were used: LH3forward (5′-ATG AAA CTC TGT GCC ATC TTT GAC-3′; positions 1886 to 1910) and LH4reverse (5′-CCA CTT TGT AGC ATC TGC ACT AAC-3; positions 2966 to 2941). All products were subsequently gel purified and sequenced for confirmation.

Animal protection experiments.

C57BL/6 mice were immunized by three consecutive intraperitoneal and subcutaneous injections of either VVHTNV/GPC (105 PFU) or VVT7 (105 PFU) (controls) administered 2 weeks apart. HTNV-specific antibody titers were determined by using a previously published enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) before infection with 100 50% lethal doses (LD50) of strain 76-118 of HTNV (4, 20). Animals were monitored for clinical symptoms twice daily, and survivors were kept for 1 month after the last of the control animals had died.

RESULTS

HTNV causes a lethal infection in adult laboratory mice.

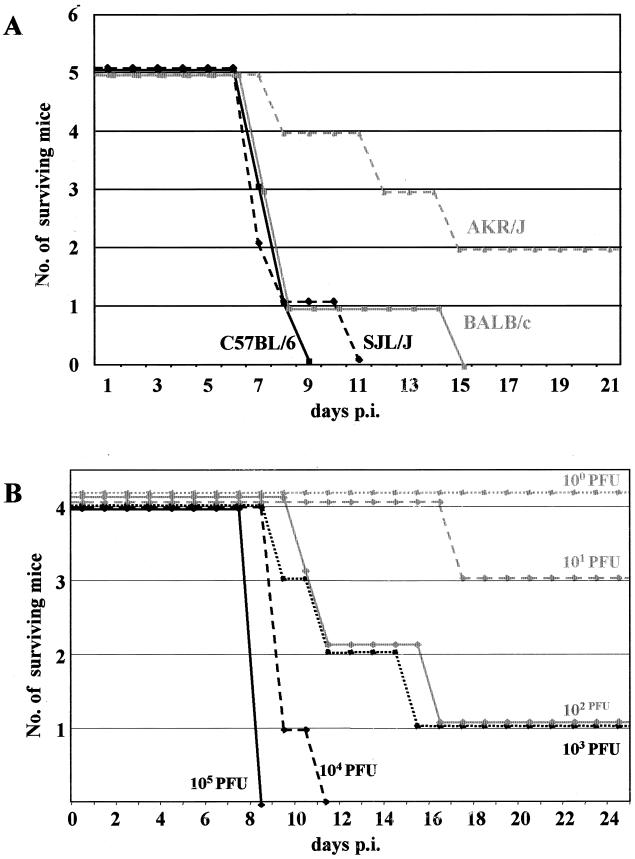

In an attempt to develop a small-animal model for hantaviruses, we tested the susceptibilities of different laboratory mouse strains. Adult C57BL/6, SJL/J, BALB/c, and AKR/J mice (8 weeks old) were intraperitoneally infected with 105 PFU of HTNV strain 76-118. At day 5 or 6 postinfection, weight loss was registered in some animals and was quickly followed by reduced activity and ruffled fur. In the late stage of the disease, the animals developed neurological symptoms, such as paralysis and tonic-clonic convulsions, which could be provoked by tactile and acoustic stimuli. The quickly progressing disease led to death in most animals within approximately 24 to 36 h after the onset of the first neurological signs (Fig. 1A). Except for AKR/J mice (two of five survived; both animals seroconverted), all other animals were susceptible to infection and showed similar but sometimes delayed disease courses. C57BL/6 seemed to be the most susceptible mouse strain; therefore, that strain was used to determine the LD50 of infection. Tenfold dilutions were prepared from the HTNV stock, and four 8-week-old mice were intraperitoneally infected with each of the dilutions (Fig. 1B). The LD50, calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (29), was approximately 60 PFU. In all further experiments, animals were challenged with an LD50 of 100.

FIG. 1.

Laboratory mice are susceptible to HTNV infection. (A) Different strains of laboratory mice were intraperitoneally infected with 105 PFU of HTNV strain 76-118. Except for AKR/J mice, all other animals were susceptible to infection and showed similar but sometimes delayed disease courses. (B) C57BL/6 mice were used to determine the LD50 by intraperitoneal infection with 10-fold dilutions of the virus stock. The LD50 was calculated to be approximately 60 PFU. (C) Knockout mice lacking a functional receptor for IFN-α/β (IFNAR-1−/− mice) were infected intraperitoneally with 100 LD50 of HTNV. Weight loss was registered earlier for IFNAR-1−/− mice than for C57BL/6 mice. The greater susceptibility to infection may indicate a role of IFN-α/β in antiviral defense. p.i., postinfection.

HTNV-infected mice benefit from the antiviral activity of IFN-α/β.

Knockout mice lacking a functional receptor for IFN-α/β (IFNAR-1−/− mice) were tested next for their susceptibility to HTNV. These animals lack the β subunit of the IFN-α/β receptor and thus are more sensitive to various virus infections (6, 10, 25). C57BL/6 control and IFNAR-1−/− mice were infected intraperitoneally with 100 LD50 of HTNV. With IFNAR-1−/− mice, weight loss was registered much earlier (4 days postinfection). Once the animals became symptomatic, there was no difference in the disease courses between the two study groups (Fig. 1C). This finding indicates an important role of IFN-α/β in the defense against HTNV.

HTNV appears to cause a systemic infection, with the central nervous system being the primary target.

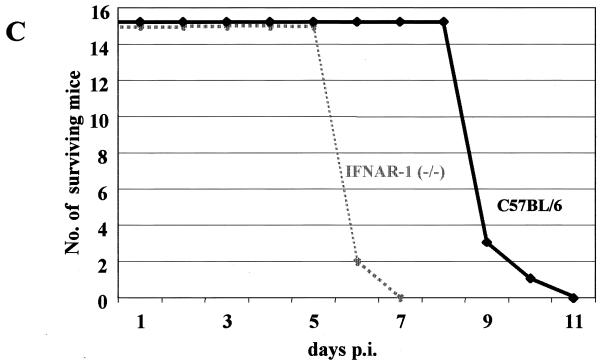

In order to better describe and understand the lethal neurological disease in laboratory mice, we performed RT-PCR, histological, immunohistochemical, and in situ hybridization analyses on material of several organs taken from infected and uninfected C57BL/6 mice. In the first step, RT-PCR performed with L segment-specific oligonucleotides generated a 1,080-bp specific amplicon (Fig. 2). HTNV RNA was detected in the brain, lungs, liver, kidneys, and spleen, indicating a systemic infection. Since sporadically nonspecific amplicons of minor sizes were detected, all amplicons of the expected size were sequenced. The sequences were identical to those of the virus stock that we used for intraperitoneal infection (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

HTNV causes a systemic infection in laboratory mice. RNA was isolated from different organs, and RT-PCR was performed with L segment-specific oligonucleotides (see Material and Methods). The amplicons were analyzed on 1% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide. HTNV-specific amplions (1,080 bp) were detected in all organs tested. Lanes 1 and 10, DNA standards; lanes 2 and 9, negative PCR control (H2O, no template); lane 3, negative control for RNA isolation (no template); lanes 4 to 8, samples from the liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, and brain, respectively.

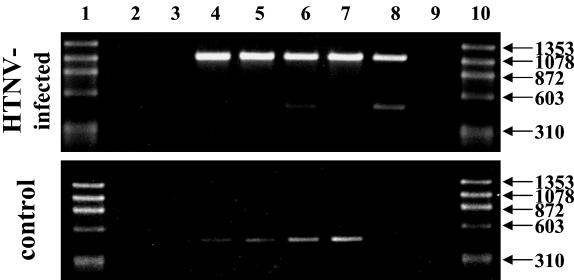

Histological examination of organ samples provided further evidence of a systemic infection of the animals, with the most prominent lesions located in the central nervous system, particularly the brain. Throughout the brain, distinct signs of vasculitis with perivascular edema and infiltration of mononuclear cells were found (Fig. 3). Focally, neurons displayed eosinophilic cytoplasm and basophilic, often fragmented, nuclei a sign of neuronal apoptosis. Based on the histological findings, which correlated well with the clinical symptoms, we concluded that the animals died of acute encephalitis. The liver showed focal centrilobular necrosis with infiltration of mononuclear cells and large macrophage-like cells with phagocytic activity (Fig. 3). The histological findings in the spleen resembled those of a viral infection, with hyperplastic germ centers and giant cell formation (data not shown). No significant alterations were found in the kidneys and lungs.

FIG. 3.

HTNV infection causes encephalitis in laboratory mice. Sections of different organs were HE stained. The brain sections show perivascular edema (arrow in upper panel) with massive mononuclear cell infiltration in and around vessel walls and leukocytes which adhere to endothelial cells. Strongly basophilic nuclear fragments indicate apoptosis (arrows in lower panel). The liver sections show focal large necrotic areas (arrows in upper panel). A higher magnification of the sections shows giant cells with prominent nucleoli (arrow in lower panel) and a mononuclear cell infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and monocytes.

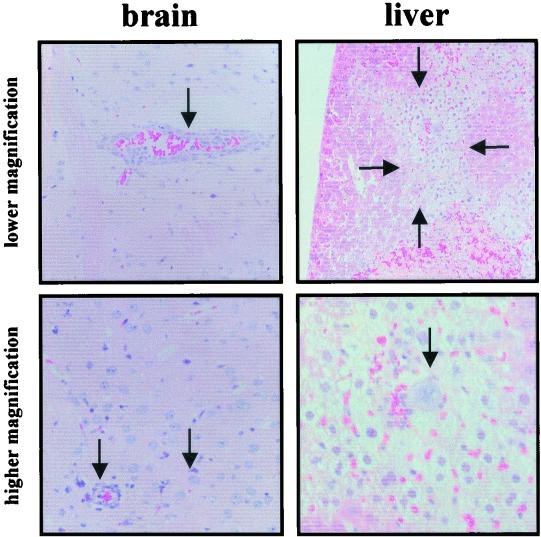

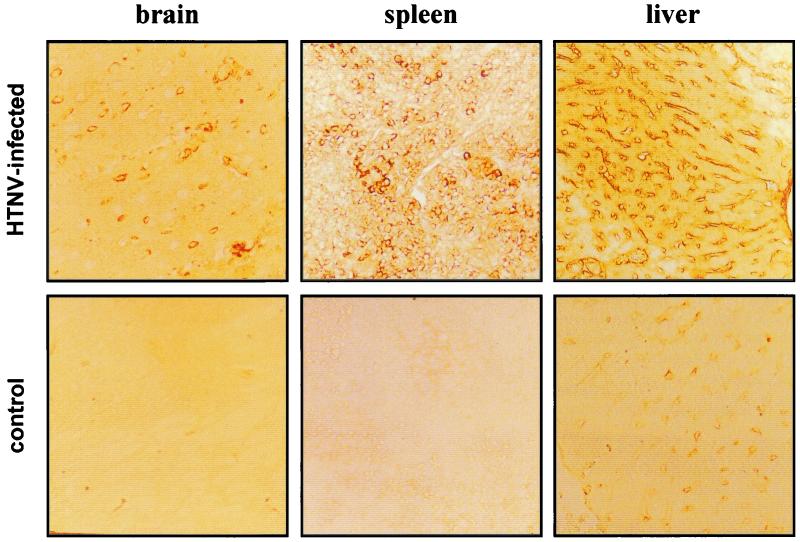

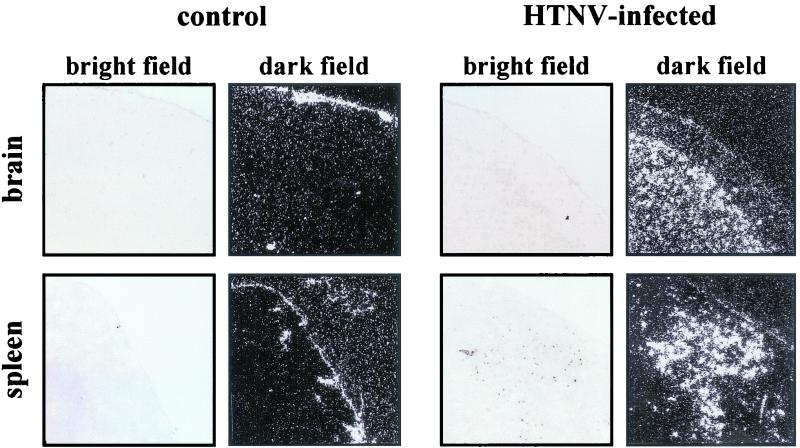

In order to associate the histological lesions with hantavirus replication, we performed immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization analyses. As expected, we detected viral proteins in neurons near areas of necrosis in the brain (Fig. 4). In the spleen, positive signals were observed in lymphocytes; in the liver, viral antigen was found in perisinusoidal cells, such as Kupffer cells, and central vein endothelial cells. Corresponding organ sections of noninfected animals remained negative (Fig. 4, bottom panel). In situ hybridization was performed with an S segment-specific, 32P-labeled RNA probe. Signs of viral replication were detected, particularly in neurons (Fig. 5). Viral RNA distribution in the spleen sections correlated with that of viral antigen detected by immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 4 and 5). Although the results of histological and immunohistochemical analyses revealed strong evidence for virus infection of the liver, we failed to detect a positive signal for viral RNA in sections of this organ.

FIG. 4.

HTNV antigen can be detected in the brain, spleen, and liver. Sections from the brain, spleen, and liver were prepared for immunohistochemical analysis (see Material and Methods). To detect viral antigen, the sections were incubated with a mouse polyclonal antiserum against HTNV (1:100 dilution) followed by rabbit anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:6,000). Viral antigen was detected in neurons (brain), endothelial cells (brain and liver), and lymphoid cells (spleen).

FIG. 5.

HTNV nucleic acid can be detected in the brain and spleen. Sections from the brain and spleen were prepared for in situ hybridization with an S segment-specific, 32P-labeled RNA probe that was 350 nucleotides long (see Material and Methods). Sections were analyzed by bright- and dark-field microscopy. Viral nucleic acid was detected in neuronal cell layers of the brain and hyperplastic germ centers of the white pulp of the spleen.

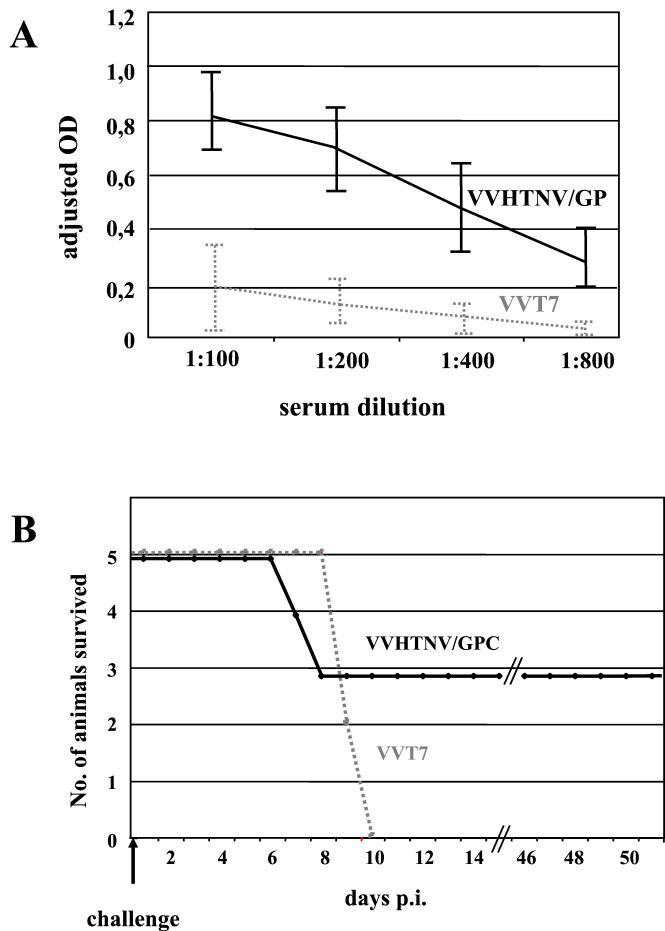

Immunized mice are partially protected against a lethal HTNV challenge.

The clinical course, distribution of viral antigen and RNA, and pathologic findings basically matched and indicated that HTNV caused a systemic lethal infection in adult immunocompetent mice. In order to provide further proof that HTNV was the causative agent of the encephalitis in the animals, we performed protection experiments. Adult C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the glycoprotein precursor of strain 76-118 of HTNV (23). The virus was administered by three consecutive intraperitoneal and subcutaneous injections of 105 PFU at intervals of 2 weeks. Following the final immunization, antibody titers against HTNV were determined by using a previously described ELISA (4, 20). All immunized animals developed an antibody response (titers, 1:400 to 1:800), indicating successful immunization. Control mice, which were immunized with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase under the same scheme, did not react positively in the ELISA (Fig. 6A). Subsequently, both groups of animals were challenged intraperitoneally with 100 LD50 of HTNV. While all control animals died, 60% of the immunized animals (three of five) were protected against the lethal challenge (Fig. 6B). This result indicates that protective immunity can be achieved and supports the notion that HTNV was the causative agent of the lethal encephalitis in the animals.

FIG. 6.

Immunized mice are partially protected against lethal HTNV challenge. Adult C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally and subcutaneously immunized three times with 105 PFU of recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing either the glycoprotein precursor of HTNV (VVHTNV/GPC) or the T7 RNA polymerase (VVT7). Prior to challenge with HTNV (100 LD50), antibody titers were determined by using an HTNV-specific ELISA. In contrast to the control animals (VVT7), all immunized animals (VVHTNV/GPC) developed an antibody response, indicating successful immunization (A). While all control animals died, protective immunity was achieved in 60% of the immunized animals (three of five) (B). OD, optical density; p.i., postinfection.

DISCUSSION

One of the priorities in hantavirus research is the development of small-animal models. A disease model was recently established for HPS by infection of Syrian hamsters with ANDV, one of the South American New World hantaviruses (12). Although several species of rodents, rabbits, and nonhuman primates have been infected with Old World hantaviruses, only humans and eventually macaques (8, 19) have been shown to present symptoms similar to those of HFRS. In the past, symptomatic or lethal disease courses were reported only following infection of newborn or immunodeficient laboratory mice or rats (13, 18, 21, 24, 39, 40). Hamsters and bank voles have been used for challenge studies with HTNV (11) and PUUV (36). Again, however, all challenges resulted in persistent infections with few or no clinical symptoms. Here we have shown that HTNV, the prototype of Old World hantaviruses, causes lethal encephalitis in adult immunocompetent laboratory mice.

The neurological disease associated with the HTNV infection of adult laboratory mice in this study is in contrast to HFRS and HPS in humans. Interestingly, previous studies of hantavirus infections in newborn and immunodeficient rodents also described neurological symptoms, including cachexia and pareses (13, 18, 21, 24, 39, 40). In contrast to what was seen with the model described here, the outcome and severity of the disease in partially immunocompetent animals differed from survival to delayed death for up to 30 or more days postchallenge. A change in clinical symptoms as a consequence of a different virus target organ is not a novel observation with hantaviruses. This finding was also noted with the discovery of HPS in 1993 and actually delayed the laboratory diagnosis of this emerging disease (1, 20, 26). However, all symptomatic and more severe infections with hantaviruses in any host seem to be systemic infections (for this model, see Fig. 2). A common hallmark for all of these hantavirus infections seems to be the disturbance of endothelial cell function (27, 41). A similar observation was made with this model when histological findings showed cerebral vasculitis (Fig. 3 and 4). A disturbance in oxygen supply could therefore be a reason for neuronal apoptosis, which was observed in many parts of the brain (Fig. 3 and 4). These findings implicate endothelial cells as a general target for hantaviruses independent of the host species.

A distinct, unexpected clinical manifestation may imply the possibility of a different disease-causing agent or substance. Our investigations demonstrated a good correlation among the clinical symptoms, the cause of death, and the histological findings. At locations with histological alterations, hantavirus antigen and RNA were detected, indicating that the changes were caused by hantavirus replication (Fig. 3 to 5). Furthermore, the protection of animals following vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the HTNV glycoprotein precursor strongly supported the involvement of HTNV in the pathological process (Fig. 6). Finally, the negative microbiological test results excluded infections with other mouse pathogens which could have been directly or indirectly responsible for the lethal disease.

HTNV is sensitive to the antiviral action of human IFN-α (35), which is mediated by effector proteins, such as the MxA protein (9). It was previously demonstrated that MxA inhibits HTNV replication by interacting with an early step of virus replication (7). The mouse genome also encodes Mx proteins (Mx1 and Mx2) which possess antiviral activity (9). It is unlikely that the nuclear Mx1 protein interferes with the replication of HTNV, since hantaviruses are not known to have a nuclear phase in their replication cycle. However, the cytoplasmic Mx2 protein seems to inhibit hantavirus replication, as was recently shown for HTNV and Seoul virus (14). Thus, it was tempting to speculate that the IFN-induced expression of Mx2 contributes to the prolonged incubation time observed in HTNV-infected C57BL/6 control mice compared to knockout mice lacking a functional IFN-α/β receptor (Fig. 1C). However, this was not the case, because C57BL/6 mice, like most other inbred mice, have only nonfunctional Mx genes (33, 34). Therefore, mice must possess additional IFN-induced defense mechanisms which interfere with the replication of HTNV.

Future experiments should examine whether the model will work for other, particularly Old World, hantaviruses. Preliminary attempts to infect C57BL/6 mice with PUUV failed to induce a symptomatic infection (H. Feldmann et al., unpublished data). This result may be explained by the reservoir host for PUUV, which is Clethrionomys glareolus, belonging to the subfamily Microtinae of the family Muridae (37, 38). C57BL/6 mice, however, belong to the subfamily Murinae, as does Apodemus agrarius, the primary reservoir host for HTNV. Interestingly, in contrast to ANDV, the closely related Sin Nombre virus does not cause any disease in Syrian hamsters (12); the reason is unknown. Therefore, the genetic background of the host species may determine the susceptibility to hantaviruses. At this point, we cannot exclude the possibility that the susceptibility of laboratory mice to HTNV is due to mutations. Although this possibility seems unlikely, sequence determination for this particular HTNV has indeed resulted in a few S (two nucleotide and two amino acid changes) and M (seven nucleotide and four amino acid changes) segment mutations compared to the published sequence for strain 76-118 of HTNV (B. Anheier and H. Finkemeier, unpublished data).

In conclusion, we have shown that strain 76-118 of HTNV can cause lethal systemic infections in several inbred strains of adult immunocompetent laboratory mice. The major target organ is the central nervous system, and the cause of death is acute encephalitis. Even though this is not a disease model for HFRS, it has the added advantage of incorporating the genetic tools available for mice. This mouse model, as well as the Syrian hamster model for HPS, will be helpful in the development of therapeutic and prophylactic measurements against hantavirus infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steffi Lindow and Daryl Dick for technical assistance and Sandra Berthel, Guido Schemken, Nicole Beausoleil, and John Copps for assistance in animal care and manipulations. In addition, we thank Anke Feldmann for advice on in situ hybridization and Daryl Dick for editorial comments.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Fe 286/5-1, SFB 286-A7, and SFB 405-B10) and the Volkswagen-Stiftung (Az: I/72087).

REFERENCES

- 1.Duchin, J. S., F. T. Koster, C. J. Peters, G. L. Simpson, B. Tempest, S. R. Zaki, T. G. Ksiazek, P. E. Rollin, S. T. Nichol, E. T. Umland, R. L. Moolenaar, S. E. Reef, K. B. Nolte, M. M. Gallaher, J. C. Butler, R. F. Breiman, and The Hantavirus Study Group. 1994. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: a clinical description of 17 patients with a newly recognized disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 330:949-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott, R. M. 1990. Molecular biology of Bunyaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 71:501-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldmann, A., M. K. Schaefer, W. Garten, and H. D. Klenk. 2000. Targeted infection of endothelial cells by avian influenza virus A/FPV/Rostock/34(H7N1) in chicken embryos. J. Virol. 74:8018-8027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldmann, H., A. Sanchez, S. Morzunov, C. F. Spiropoulou, P. E. Rollin, T. G. Ksiazek, C. J. Peters, and S. T. Nichol. 1993. Utilization of autopsy RNA for the synthesis of the nucleoprotein antigen of a newly recognized virus associated with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Virus Res. 30:351-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldmann, H. March 2000, posting date. Hantaviruses, p. 1-8. In R. M. Atlas, M. M. Cox, S. F. Gilbert, J. W. Roberts, and B. A. Wood (ed.), Encyclopedia of life sciences. [Online.] Nature Publishing Group, London, England. http://www.els.net.

- 6.Fiette, L., C. Aubert, U. Mueller, S. Huang, M. Aguet, M. Brahic, and J. F. Bureau. 1995. Theiller's virus infection in 129Sv mice that lack the interferon alpha/beta or interferon gamma receptor. J. Exp. Med. 181:2069-2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frese, M., G. Kochs, H. Feldmann, C. Hertkorn, and O. Haller. 1996. Inhibition of bunyaviruses, phleboviruses, and hantaviruses by human MxA protein. J. Virol. 70:915-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groen, J., M. Gerding, J. Koeman, P. Roholl, G. van Amerogen, H. Jordans, H. Niesters, and A. Osterhaus. 1995. A macaque model for hantavirus. J. Infect. Dis. 172:38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haller, O., M. Frese, and G. Kochs. 1998. Mx proteins: mediators of innate rsistance to RNA viruses. Rev. Sci. Tech. 17:220-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hefti, H. P., M. Frese, H. Landis, C. Di Paolo, A. Aguzzi, O. Haller, and J. Pavlovic. 1999. Human MxA protein protects mice lacking a functional alpha/beta interferon system against La Crosse virus and other lethal viral infections. J. Virol. 73:6984-6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooper, J. W., K. I. Kamrud, F. Elgh, D. M. Custer, and C. S. Schmaljohn. 1999. DNA vaccination with hantavirus M segment elicits neutralizing antibodies and protects against Seoul virus infection. Virology 255:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooper, J. W., T. Larsen, D. M. Custer, and C. S. Schmaljohn, C. S. 2001. A lethal disease model for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Virology 289:6-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huggins, J. W., G. R. Kim, O. M. Brand, and K. T McKee Jr. 1986. Ribavirin therapy for Hantaan virus infection in suckling mice. J. Infect. Dis. 153:489-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin, H. K., K. Yoshimatsu, A. Takada, M. Ogino, A. Asano, J. Arikawa, and T. Watanabe. 2001. Mouse Mx2 protein inhibits hantavirus but not influenza virus replication. Arch. Virol. 146:41-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, C. B., and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2001. Replication of hantaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 256:15-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, K. M. 1999. Introduction, p. 1-6. In H. W. Lee, C. Calisher, and C. S. Schmaljohn (ed.), Manual of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. W. H. O. Collaborating Center for Virus Reference and Research (Hantaviruses), Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Seoul, Korea.

- 17.Kanerva, M., J. Mustonen, and A. Vaheri. 1998. Pathogenesis of Puumala and other hantavirus infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 8:67-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, G., and J. McKee. 1985. Pathogenesis of Hantaan virus infection in suckling mice: clinical virologic, and serologic observations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 34:388-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klingstrom, J., A. Plyusnin, A. Vaheri, and A. Lundkvist. 2002. Wild-type Puumala hantavirus infection induces cytokines, C-reactive protein, creatine, and nitric oxide in cynomolgus macaques. J. Virol. 76:444-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ksiazek, T. G., C. J. Peters, P. E. Rollin, S. Zaki, S. T. Nichol, C. F. Spiropoulou, S. Morzunov, A. Sanchez, H. Feldmann, A. S. Khan, K. Wachsmuth, and J. C. Butler. 1995. Identification of a new north American hantavirus that causes acute pulmonary insufficiency. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 52:117-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurata, T., T. Tsai, S. Bauer, and J. B. McCormick. 1983. Immunofluorescence studies of disseminated Hantaan virus infection of suckling mice. Infect. Immun. 41:391-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, J. S., J. Lähdevirta, F. Koster, and H. Levey. 1999. Clinical manifestations and treatment of HFRS and HPS, p. 17-38. In H. W. Lee, C. Calisher, and C. S. Schmaljohn (ed.), Manual of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. W. H. O. Collaborating Center for Virus Reference and Research (Hantaviruses), Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Seoul, Korea.

- 23.Loeber, C., B. Anheier, S. Lindow, and H. Feldmann. 2001. The hantavirus glycoprotein precursor is cleaved at the conserved pentapeptide ‘WAASA.’ Virology 289:224-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKee, K., Jr., G. Kim, D. Greem, and C. J. Peters. 1985. Hantaan virus infection in suckling mice: virologic, and pathologic correlates. J. Med. Virol. 17:107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller, U., U. Steinhoff, L. F. L. Reis, S. Hemmi, J. Pavlovic, R. M. Zinkernagel, and M. Aguet. 1994. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science 264:1918-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichol, S. T., C. F. Spiropoulou, S. Morzunov, P. E. Rollin, T. G. Ksiazek, H. Feldmann, A. Sanchez, J. Childs, S. Zaki, S., and C. J. Peters. 1993. Genetic identification of hantavirus associated with an outbreak of acute respiratory illness. Science 62:914-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papadimitriou, M. 1995. Hantavirus nephropathy. Kidney Int. 48:887-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters, C. J., G. L. Simpson, and H. Levy. 1999. Spectrum of hantavirus infection: hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Annu. Rev. Med. 50:531-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmaljohn, C. S., and B. Hjelle. 1997. Hantaviruses: a global disease problem. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:95-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmaljohn, C. S., and J. W. Le Duc. 1998. Bunyaviridae, p. 601-628. In L. H. Collier, A. Balows, and M. Sussman (ed.), Topley and Wilson's microbiology and microbial infections, 9th ed. Arnold, London, England.

- 32.Schmaljohn, C. S., and S. T. Nichol. 2001. Hantaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 256:1-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staeheli, P., R. Grob, E. Meier, J. G. Sutcliffe, and O. Haller. 1988. Influenza virus-susceptible mice carry Mx genes with a large deletion or a nonsense mutation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:4518-4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staeheli, P., and J. G. Sutcliffe. 1988. Identification of a second interferon-regulated murine Mx gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:4524-4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura, M., H. Asada, K. Kondo, M. Takahashi, and K. Yamanishi. 1987. Effects of human and murine interferons against hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) virus (Hantaan virus). Antiviral Res. 8:171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ulrich, R, A. Lundkvist, H. Meisel, D. Koletzki, K. B. Sjölander, H. R. Gelderblom, G. Borisova, P. Schnitzler, G. Darai, and D. H. Krüger. 1998. Chimaeric HBV core particles carrying a defined segment of Puumala hantavirus nucleocapsid protein evoke protective immunity in an animal model. Vaccine 16:272-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viro, P., and J. Niethammer. 1982. Clethrionomys glareolus (Schreber, 1780)—Rötelmaus, p. 108-146. In J. Niethammer and F. Krapps (ed.), Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas, Band 2/I. Nagetiere II. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden, Germany.

- 38.Wilson, D. E., and D. A. M. Reeder. 1993. Mammal species of the world, 2nd ed. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- 39.Yamanouchi, T., K. Domae, O. Tanishita, Y. Takahashi, K. Yamanishi, M. Takahashi, and T. Kurata. 1984. Experimental infection in newborn mice and rats by hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) virus. Microbiol. Immunol. 28:1345-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshimatsu, K., J. Arikawa, S. Ohbora, and C. Itakura. 1997. Hantavirus infection in SCID mice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 59:863-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zaki, S. R., P. W. Greer, L. M. Coffield, C. S. Goldsmith, K. B. Nolte, K. Foucar, R. M. Feddersen, R. E. Zumwalt, G. L. Miller, A. S. Khan, P. E. Rollin, T. G. Ksiazek, S. T. Nichol, B. W. J. Mahy, and C. J. Peters. 1995. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome—pathogenesis of an emerging infectious disease. Am. J. Pathol. 146:552-579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]