Abstract

The Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) lef-6 gene was previously shown to be necessary for optimal transcription from an AcMNPV late promoter in transient late expression assays. In the present study, we examined the expression and cellular localization of lef-6 during the AcMNPV infection cycle and generated a lef-6-null virus for studies of the role of lef-6 in the infection cycle. Transcription of lef-6 was detected from 4 to 48 h postinfection, and the LEF-6 protein was identified in dense regions of infected cell nuclei, a finding consistent with its potential role as a late transcription factor. To examine lef-6 in the context of the AcMNPV infection cycle, we deleted the lef-6 gene from an AcMNPV genome propagated as an infectious BACmid in Escherichia coli. Unexpectedly, the resulting AcMNPV lef-6-null BACmid (vAclef6KO) was able to propagate in cell culture, although virus yields were substantially reduced. Thus, the lef-6 gene is not essential for viral replication in Sf9 cells. Two “repair” AcMNPV BACmids (vAclef6KO-REP-P and vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P) were generated by transposition of the lef-6 gene into the polyhedrin locus of the vAclef6KO BACmid. Virus yields from the two repair viruses were similar to those from wild-type AcMNPV or a control (BACmid-derived) virus. The lef-6-null BACmid (vAclef6KO) was further examined to determine whether the deletion of lef-6 affected DNA replication or late gene transcription in the context of an infection. The lef-6 deletion did not appear to affect viral DNA replication. Using Northern blot analysis, we found that although early transcription was apparently unaffected, both late and very late transcription were delayed in cells infected with the lef-6-null BACmid. This phenotype was rescued in viruses containing the lef-6 gene reinserted into the polyhedrin locus. Thus, the lef-6 gene was not essential for either viral DNA replication or late gene transcription, but the absence of lef-6 resulted in a substantial delay in the onset of late transcription. Therefore, lef-6 appears to accelerate the infection cycle of AcMNPV.

The infection cycle of the Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) can be subdivided into three major phases of viral transcription: early, late, and very late (7, 23). Early gene expression occurs after uncoating of the viral genome in the host cell nucleus and is mediated by host RNA polymerase II. Studies with inhibitors of DNA replication suggest that the transition between early and late gene transcription requires prior viral DNA replication (38). Late transcription is mediated by an α-amanitin-resistant, virus-induced RNA polymerase activity that is detected after DNA replication begins (11, 15). To begin to examine the nature of the late RNA polymerase activity, Passarelli and Miller (33) developed a transient late expression assay system that was subsequently used to identify a number of viral late expression factor (lef ) genes (18, 24, 37, 39). In this assay, transfection and transient expression of 19 to 20 lef genes are necessary to support optimal levels of transient expression from a reporter gene under the control of an AcMNPV late promoter. Using a transient origin-dependent DNA replication assay to identify genes associated with viral DNA replication, ca. 10 (lef-1, lef-2, lef-3, p143, p35, ie-1, ie-2, lef-7, DNApol, and pe-38) of the original 19 lef genes were identified as “replication”-related genes (1, 17, 21, 24, 39). Recently, by using an infectious BACmid containing a knockout in the lef-11 gene, we identified lef-11 as an additional gene required for viral DNA replication (20a). The remaining eight lef genes (lef-4, lef-8, lef-9, p47, lef-5, lef-6, lef-10, and lef-12) are believed to be involved more directly in late transcription. More recently, a late RNA polymerase complex was purified from insect cells infected with AcMNPV, and this complex (consisting of proteins LEF-4, LEF-8, LEF-9, and P47) was shown to initiate transcription from a late promoter (13). Thus, these four LEF proteins appear to comprise major components of the late RNA polymerase. Additional studies have shown that the product of lef-4 is probably involved in RNA capping, since the LEF-4 protein has both RNA 5′-triphosphatase and guanylyltransferase activities (10, 12, 16, 28) in vitro. lef-8 and lef-9 each have predicted amino acid sequence motifs that are similar to motifs found in RNA polymerases (22, 35), but no functional data are available for LEF-8, LEF-9, or P47 proteins.

The predicted LEF-6 protein was also reported to contain some very limited sequence similarity to a subunit of the vaccinia virus RNA polymerase (34). In transient late expression assays, omission of lef-6 resulted in a reported 100-fold reduction of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity from a vp39 late promoter-CAT construct (24). However, some transcriptional activity remained (24, 34), suggesting the possibility that LEF-6 may represent an accessory factor important for regulation but not for basal levels of transcription from the late RNA polymerase. Because of the indirect nature of transient late expression assays, it is not clear whether LEF-6 plays such a role in the context of a viral infection. Studies of the expression of LEF proteins in the context of the infection cycle have been limited. Expression of lef-6 mRNA was initially examined, and transcription was mapped (34), although the LEF-6 protein has not been previously examined. In a previous study of lef genes of Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus (BmNPV), the authors were unable to generate a lef-6 knockout virus by using conventional homologous recombination in insect cells, and they concluded that lef-6 and certain other lef genes were likely to be essential for viral replication in cell culture (9). From such studies, it is unclear whether lef-6 is essential or whether lef-6 might serve an important but nonessential role.

In the current study, we examined lef-6 transcription and protein localization in infected Sf9 cells. We also generated a lef-6-null BACmid by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Using lef-6-null BACmid DNA for transfection of Sf9 cells, we were able to generate an infectious virus, although virus yields were substantially reduced in comparison with wild-type AcMNPV. The observed defect was rescued by reinsertion of the wild-type lef-6 gene into the polyhedrin locus of the same virus to generate a repair virus. We used lef-6-null and repair viruses to examine the detailed effects of the lef-6 knockout on viral replication; viral DNA replication; and early, late, and very late transcription. The results of these studies indicate that lef-6 is not essential for viral replication but that the infection cycle is substantially delayed in the absence of lef-6.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transcript analysis.

To identify transcription start sites, total RNA extracted from AcMNPV infected Sf9 cells at 12 h postinfection (p.i.) was used as a template for 5′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) analysis by using a 5′ RACE system (version 2.0; Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For 5′ RACE analysis of the lef-6 gene, the following gene-specific primers were used: lef6-GSP1 (5′-GTTTTTCTAATACATTCAAGTCGTCTAGATG-3′) and lef6-GSP2 (5′-CCGGATCCAAGAGTCACGTTCGTCGATTTCG-3′). PCR products were cloned into the SalI/XbaI site of pBluescript and sequenced to identify the transcription start site. To identify the 3′ ends of lef-6 mRNAs, total RNA extracted from 12 h p.i. AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells was used as a template for 3′ RACE analysis by using a 3′ RACE system (Life Technologies). The primer lef6-3′RACE (5′-CCGGATCCCGCCCAGAGCCACGGCTAC-3′) was used for 3′ RACE analysis. PCR products from the 3′ RACE analysis were cloned into the BamHI/SalI sites of pBluescript and sequenced to identify the cleavage and poly(A) addition site. For each analysis, three to four cloned RACE products were sequenced.

For Northern blot analysis, 5 μg of total RNA from each time point was electrophoresed on a formaldehyde-1.2% agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized to a cRNA riboprobe as described previously (20). A 33P-labeled single-stranded cRNA riboprobe was generated from a PCR product. A 343-nucleotide (nt) region of the lef-6 gene was PCR amplified from within the lef-6 open reading frame (ORF) of the AcMNPV genome. The antisense PCR primer included a terminal T7 promoter sequence (3) that was later used to generate the negative-sense lef-6 cRNA riboprobe. The PCR primers used to generate the lef-6 probe were 5′lef6-IVT (5′-CAGCGTCGACTGAACGGCAGCACGCGC-3′) and 3′lef6-IVT (5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGTCGTCGTAGTCGTCGTAGCCG-3′). The underlined sequences represent the optimal T7 promoter sequence. The PCR product was used to generate a labeled cRNA probe by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase with [α-33P]ATP (ca. 3,000 Ci/mmol; NEN, Inc.) (MAXIscript; Ambion, Inc.). The labeled cRNA probe was purified on a G-50 Spin Column (5Prime3Prime, Inc.) and hybridized to Northern blots. Membranes were imaged on a Storm PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.).

LEF-6 expression and antiserum production.

To generate an anti-LEF-6 antiserum, the lef-6 ORF was cloned into a pET expression plasmid, and protein was expressed and purified from E. coli. The lef-6 ORF was amplified from AcMNPV DNA by using Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) and two oligonucleotide primers containing flanking BamHI sites: 5′lef6pPet (5′-CGGGATCCAATGGTGTTCAACGTGTACTACAAC-3′) and 3′lef6pPet (5′-CGGGATCCGCTTGTTTTTCTAATACATTCAAGTC-3′). The resulting PCR product was digested with BamHI and cloned in frame, into the BamHI site of protein expression vector pET-14b (Novagen, Inc.). The resulting plasmid (pETlef6) expresses a product with an N-terminal six-histidine tag, followed by a thrombin cleavage site and the lef-6 ORF. The LEF-6 protein expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) was purified on HisBind Quick 900 Cartridges (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions for insoluble proteins and then concentrated by using polyethylene glycol. Purified LEF-6 protein was used to generate a polyclonal antiserum in rabbits. Anti-LEF-6 antibodies were purified as described earlier (20).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

For analysis of protein localization by immunofluorescence microscopy, Sf9 cells (2 × 106 cells/well in six-well plates containing coverslips) were infected with AcMNPV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. At 18 h p.i., infected cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in methanol at −20° for 10 min, and then air dried for 10 to 15 min. Fixed cells were incubated for 45 min in blocking buffer, incubated with the primary antibody (affinity-purified anti-LEF-6 antibodies; diluted 1:200 in PBS [pH 7.8]) for 1 h at room temperature, and then washed three times with PBS. Cells were next incubated with a secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G [Molecular Probes] diluted 1:500 in PBS [pH 7.8]) for 1 h at room temperature and then washed three times in 1× PBS. Cells were examined on an Olympus IX70 epifluorescence microscope with a Texas Red filter set.

Generation of lef-6 knockout virus.

To delete the lef-6 gene of AcMNPV, we first generated a transfer vector containing the lef-6 locus region, in which the lef-6 ORF was replaced with a CAT gene for antibiotic selection in E. coli, and a β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene. The CAT+GUS cassette was cloned between sequences that flank the lef-6 ORF (iap and orf29 flanking regions). An ∼1-kbp flanking region was PCR amplified from the AcMNPV iap gene, and the PCR product was digested with BamHI and XbaI and ligated with plasmid pBluescript (which had been previously digested with BamHI and XbaI) to generate the recombinant plasmid pBluIAP. The primers for amplification of the iap flanking region were 5′ IAP 1flank (5′-GCTCTAGACGAGTACGAGTTTGTAGTTTTAG-3′) and 3′ IAP 1flank (5′-TACACGTTGGCGGATCCTTTATTACACCAC-3′); the XhoI and BamHI sites, respectively, are underlined.

A p6.9 promoter-GUS cassette was excised from plasmid pAcGP64/GUSpolyA (see pΔSmaΔ-GUS [31]) by digesting this plasmid with BglII/HindIII. The 2.42-kbp GUS cassette was purified and ligated with plasmid pBluIAP, which was previously digested with BamHI/HindIII, to generate recombinant plasmid pBluIAPGUS. An ∼1-kb orf29 flanking region was PCR amplified from AcMNPV DNA with the primers 3′ORF29flank (5′-ACGGGCTCGAGGGTTTGGTGAACACGTTAC-3′) and 5′ORF29flank (5′-GAAAGGCTCGAGAACATGTATTAAAAATAATAATAATAAAAC-3′); the XhoI sites are underlined. The PCR product was digested with XhoI and cloned into with the XhoI site of plasmid pBluIAPGUS to generate the recombinant plasmid pBluIAPGUSorf29. Orientation was determined by using a PstI/KpnI digest. A 935-bp CAT gene cassette was PCR amplified from plasmid pRE112 (6), and the PCR product was digested with ClaI and cloned into the ClaI site of plasmid pBluIAPGUSorf29 to generate plasmid pBluIAPGUSorf29CAT. The primers used for amplification of the CAT cassette were 5′ClaICm (5′-GCATCGATTAAATACCTGTGACGGAAGAT-3′) and 3′ClaICm (5′-GCATCGATTATCACTTATTCAGGCGTAGC-3′).

To generate an AcMNPV lef-6 knockout BACmid by recombination in E. coli, we used a modification of a method described by Bideshi and Federici (4). The AcMNPV BACmid genome used in these studies was originally described as bMON14272 by Luckow et al. (25) and is commercially available (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Transfer vector pBluIAPGUSorf29CAT was digested with EagI and ApaI. The resulting linear 5.41-kbp fragment containing the GUS-CAT cassette plus the lef-6 flanking regions was isolated and cotransformed with the bMON14272 BACmid DNA into E. coli BJ5183. After overnight incubation in SOC (27), cells were plated onto Luria-Bertani agar containing 50 μg of kanamycin and 30 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. Plates were incubated at 37°C for a minimum of 24 h. Colonies resistant to kanamycin and chloramphenicol were selected, and the presence of the GUS-CAT promoter cassette and the absence of the lef-6 ORF were confirmed by Southern blot analysis and PCR analysis. The lef-6-null BACmid was named vAclef6KO.

Southern blot analysis.

To confirm deletion of the lef-6 gene from the AcMNPV genome, Southern blot hybridization analysis was used. A 522-bp DNA fragment containing the AcMNPV lef-6 gene was PCR amplified with primers 3′lef6BRNX (5′-GGAATTCCCTTTCTCAACTACGGAATAGAC-3′) and 5′lef6BRNX (5′-CGGGATCCAATGGTGTTCAACGTGTACTACAAC-3′). The PCR product was labeled with digoxigenin dUTP (DIG High Prime Labeling and Detection Starter Kit I; Roche Biochemicals) and used as a probe for Southern blot hybridization as described previously (19, 27). For Southern blots, 10 μg of DNA from each BACmid (vAclef6KO, vAc64−/+GUS, and wild-type AcMNPV) was digested with XhoI and then electrophoresed and blotted onto positively charged nylon membrane (Micron Separations, Inc.) as described previously (34). Membranes were prehybridized in 10 ml of hybridization buffer (5× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA; pH 7.7], 1× Denhardt solution, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50% formamide, 100 μg of denatured salmon sperm DNA/ml) at 42°C for ≥6 h and then hybridized in the same buffer containing the labeled probe at 42°C for ca. 15 h. The membrane was washed twice with 2× wash buffer (2× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% SDS) at room temperature for 15 min per wash and then washed twice with 0.1× wash buffer (0.1 × SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 65°C for 15 min per wash. Hybridizing DNAs were detected by color detection with nitroblue tetrazolium-BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate).

lef-6 repair and control viruses.

To generate lef-6 repair transfer vectors, we modified plasmid pFastBac1. The polyhedrin promoter from pFastBac1 was removed and replaced by a fragment containing the lef-6 ORF under the control of either the lef-6 promoter or the AcMNPV ie-1 promoter. First, a 609-bp AcMNPV ie-1 promoter or an 875-bp lef-6 promoter was PCR amplified from the AcMNPV genome with the primer pair 5′IEIpromoterSnaBI (5′-GTACGTAATCGATGTCTTTGTGATGCGCGCGACATTTTTG-3′) and 3′IEIpromoterBamHI (5′-GGGATCCCACTTGGTTGTTCACGATCTTGTC-3′) or the primer pair 5′lef-6promoterSnaBI (5′-GTACGTAAACGAGGACACGCCCCCGTTTTATTTTATC-3′) and 3′lef6promoterBamHI (5′-GGGATCCTTTATTACACCACAAATATTTTTATAAAATC-3). The PCR products were digested with SnaBI and BamHI and then ligated with pFastBac1 plasmid, which was digested with SnaBI and BamHI to remove the polyhedrin promoter. The resulting recombinant plasmids were named pFastBacie1P and pFastBaclef6P, respectively. The lef-6 ORF was PCR amplified from the AcMNPV genome with the primers 5′lef6BamHI (CGGGATCCAATGGTGTTCAACGTGTACTACAAC-3′) and 3′lef6EcoRI (5′-GGAATTCCCTTTCTCAACTACGGAATAGAC-3′). The PCR product was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and then cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI site of either pFastBaclef6P or pFastBacie1P to generate plasmid pFastBaclef6-P or plasmid pFastBaclef6-ie1P, respectively. Plasmid pFastBaclef6-P contains the lef-6 ORF under the control of its own promoter, and plasmid pFastBaclef6-i.e.1-P contains the lef-6 ORF under the control of an AcMNPV ie-1 promoter. lef-6 repair BACmids were generated by moving the lef-6 gene from pFastBaclef6-ie1-P or pFastBaclef6-P into the lef-6-null BACmid by transposition according to the method of Luckow et al. (25). DH10B cells were transformed with helper plasmid pMON7124 (a plasmid containing Tn7 transposition functions). Competent DH10B cells containing the pMON7124 helper plasmid were cotransformed with (i) either pFastBaclef6-P or pFastBaclef6ie1-P DNA and (ii) vAclef6KO DNA. After 6 h of incubation at 37°C in SOC, cells were selected on media containing kanamycin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and tetracycline and restreaked onto fresh plates to verify the phenotype, which was confirmed by PCR (20a). The repair virus containing the lef-6 gene and its own promoter was named vAclef6KO-REP-P, and the repair virus containing the lef-6 gene under the ie-1 promoter was named vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P. As an additional control in some experiments, we also included a BACmid-derived control virus that carries a GUS reporter gene under the control of the p6.9 late promoter. This control virus, named vAcgp64−/Acgp64+gus, is referred to as vAc64−/+GUS in the present study. vAc64−/+GUS was generated from a gp64-null AcMNPV BACmid in which both the wild-type AcMNPV gp64 gene and a p6.9-GUS reporter gene were reinserted into the polyhedrin locus by transposition as described above. The construction and characterization of this virus is described elsewhere (25a).

PCR confirmation of recombinant BACmids.

To confirm the lef-6 knockout BACmid by PCR analysis, two pairs of specific PCR primers were used to confirm the insertion of the GUS-CAT cassette into the lef-6 locus of bMON14272. For each primer pair, one primer corresponded to sequences within the inserted sequence (the GUS or CAT ORF), and the second primer was from the baculovirus genome, just outside of the sequence used for recombination. The first primer pair consisted of GUSprimer (5′-CGC GCT TTC CCA CCA ACG CTG ATC AAT TCC-3′) and lef-6virus3′detect (5′-CACAGCATACCGTGGTCGGATCAC-3′). The second primer pair consisted of 3036primer (5′-CAAGGCGACAAGGTGCTGATGC-3′) and lef6-5′detect (5′-CAAGTATGTGGACGTGTGCTCTATCAGC-3′). To confirm the absence of lef-6 in the lef-6-null BACmid, the following primer sequences (from within the lef-6 ORF) were used for PCR analysis: 3′lef6BRNX (5′-GGAATTCCCTTTCTCAACTACGGAATAGAC-3′) and 5′lef6BRNX (5′-CGGGATCCAATGGTGTTCAACGTGTACTACAAC-3′). A similar strategy was used to confirm the reinsertion of the lef-6 gene into the polyhedrin locus of the lef-6-null BACmid: a primer pair consisting of one primer from the within the inserted sequence (between the two Tn7 attachment sites) and another primer from sequence within the BACmid (outside the two Tn7 attachment sites). The primers consisted of M13reverse (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′) and 5′FastBac (5′-GGACTCTAGCTATAGTTCTAGTGG-3′).

lef-6 virus growth curve.

For virus growth curves, Sf9 cells (3 × 105) were infected in triplicate with each virus (AcMNPV, vAclef6KO, vAclef6KO-REP-P, vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P, and vAc64−/+Gus) at an MOI of 5. This represents infection at five infectious units (IU) per cell, where one IU = 50% tissue culture infective dose(s) (TCID50) × 0.69 (32). After a 1-h infection period, cells were washed three times with TNMFH medium, and supernatants were collected at the indicated times p.i. The titers of all supernatants were determined by TCID50 on Sf9 cells (32). The data from each time point represent the accumulated infectivity from infection through the indicated time.

Dot blot analysis of viral DNA replication.

To quantify viral DNA replication in infected cells, Sf9 cells were infected as described above and viral DNAs were detected and quantified at various times p.i. by using Southern dot blot hybridization assays (9, 36). Cell monolayers (2 × 106 cells) in each well of a six-well plate were infected with each virus (AcMNPV, vAclef6KO, vAclef6KO-REP-P, vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P, and vAc64−/+Gus) at an MOI of 10. At 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h p.i., cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The cell pellet was washed twice with PBS and then diluted in PBS, and 104 cells were used for each dot blot. A cell pellet of 104 cells was resuspended in 500 μl of 0.4 M NaOH-10 mM EDTA solution, incubated at 100°C for 10 min, and blotted onto Magnacharge nylon transfer membrane (MSI Micron Separation, Inc.) by using a dot blot apparatus (Bio-Dot SF; Bio-Rad, Inc.). Samples were hybridized with a 32P-labeled AcMNPV DNA probe (3.5 × 108 cpm/μg) labeled by random priming by using a DECAprimeII Random Priming DNA Labeling Kit (Ambion). The blot was visualized by autoradiography, and the bound probe was quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis.

For RNA isolation for Northern blotting and transcript mapping studies, Sf9 cells were plated in six-well plates (2 × 106 cells/well), and each well of cells was infected at an MOI of 5. Total RNAs from infected cells were isolated at various times p.i. by using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. After precipitation in ethanol, RNA pellets were washed with 1 ml of 70% ethanol and then dried and resuspended in 50 μl of water. For Northern blot analyses, 5 μg of total RNA isolated from infected cells at each selected time point was electrophoresed on a formaldehyde-1.2% agarose gel essentially as described previously (5). rRNAs from each sample were used as a loading control for Northern blots. RNA was blotted onto Magnacharge nylon transfer membrane. cRNA riboprobes for hybridization were generated by first PCR amplifying selected regions from the genes p6.9 (190 bp), p10 (303 bp), vp39 (1.035 kbp), and ie-1 (1.35 kbp). A single fragment of 1,614 bp was amplified from the p24 to alk-exo region containing p24 capsid, gp16, pp34-pep, 132-ORF, and alk-exo genes. In each primer pair used for PCR, the downstream PCR primer included a terminal T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence that was later used to generate a negative-sense cRNA riboprobe. The PCR primers used to generate the different probes were ie-1 (5′ IE1 [5′-CCAACCATCGGCAACTGGAACTAAACGGAAGC-3′] and 3′ IE1 [5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCGCAAACGTTATAGCG-3′]), vp39 (5′VP39 [5′-CAATATGGCGCTAGTGCCCGTGGGTATGGC-3′] and 3′VP39 [5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCCTCCACCTGCTTCGCCTGC-3′]), p6.9 (5′p6.9 [5′-CATGGTTTATCGTCGCCGTCGCCGTTCTTC-3′] and 3′p6.9 [5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTAATAGTAGCGTGTTCTG-3′]), p10 (5′p10 [5′-TCAAAGCCTAACGTTTTGACGCAAATTTTAGAC-3′] and 3′p10 [5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTACTTGGAACTGCGTTTAC-3′]), and p24 to alk-exo (orf133) (5′orf133 [5′-GACGTATCCCATGGCCTATTTTGTCAATACCG-3′] and 3′orf133 [5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGTTTAAATGATCGTGTTTGG-3′]).

The underlined sequences represent the optimal T7 promoter sequence (3). PCR products from the above genes were used to generate labeled cRNA probes by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (MAXIscript; Ambion) and [α-32P]UTP (ca. 3,000 Ci/mmol; NEN Life Science Products, Inc.) according to the manufacturers' protocols. Labeled riboprobes were purified on G-50 Spin Columns (Princeton Separations, Inc.) and used for Northern blot hybridizations. For Northern blotting, membranes were prepared and hybridized as described elsewhere (Lin and Blissard, unpublished) and then imaged with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

GUS activity assay.

To examine the activity from the p6.9-GUS reporter gene in recombinant viruses, GUS activity was determined by using a GUS detection kit according to the instructions from the manufacturer (Sigma, Inc.). For each assay, cell monolayers (3 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates) were infected with vAclef6KO, vAclef6KO-REP-P, or vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P, and cells were collected at various times p.i. and then lysed in 200 μl of 1× extraction buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol; pH 7.0). For each assay reaction, 10 μl of 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronide (4-MUG) substrate was mixed with 5 μl of 1× extraction buffer, preincubated for 1 to 2 min at 37°C, and then added to 5 μl of cell extract and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 10 μl of stop solution (1 M sodium carbonate). To generate a standard curve, 4-methylumbelliferone was used, and each GUS assay result was within the linear range of results from the standard curve.

RESULTS

lef-6 transcriptional analysis.

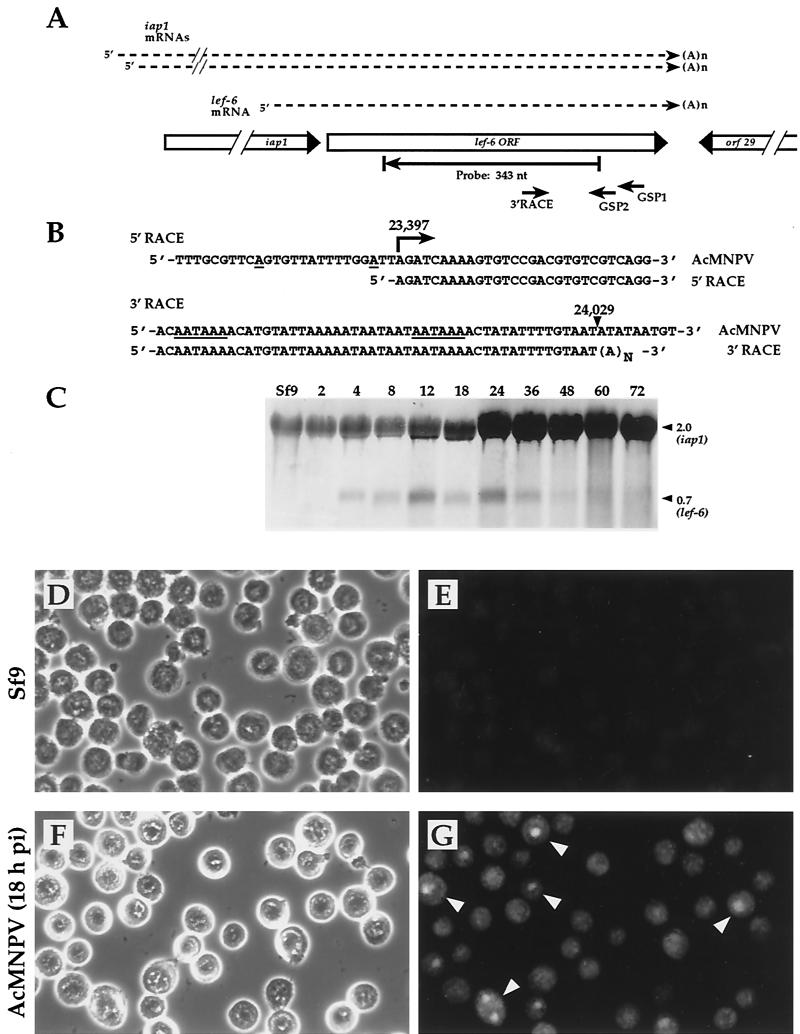

lef-6 transcription was previously studied, and transcription start sites were mapped at two positions upstream of the lef-6 ORF (positions 23381 and 23394 on the AcMNPV genome [2, 34]). Using 5′ RACE analysis, we confirmed initiation of transcription within this region, although 5′ RACE analysis identified a single transcription start site at position 23397, a position 16 and 3 nt downstream of the previously identified start sites (Fig. 1B). We also examined the 3′ end of the lef-6 transcripts by 3′ RACE analysis. The 3′ ends of the lef-6 transcripts were previously mapped to approximate positions 23995 and 24011 by S1 nuclease analysis (34). Using 3′ RACE, we mapped a single 3′ end at nt 24029, 20 nt downstream of a consensus polyadenylation signal (Fig. 1B). Northern blot analysis with a probe from within the lef-6 ORF showed that a lef-6 mRNA of ca. 0.7 kb was present from 4 to 48 h p.i., and trace amounts of this transcript may be present at later times (Fig. 1C). lef-6 transcripts were detected most abundantly at 12 and 24 h p.i. By using the antisense lef-6 probe, an overlapping transcript of ca. 2.0 kb was also observed throughout the infection cycle and in mock-infected cells. The large band hybridizing in mock-infected cells appears to result from cross-hybridization of the probe with rRNA, and the increase in the signal later in infection likely represents the appearance of the iap1 transcript, which was previously shown to migrate at that size and to overlap with the lef-6 transcript (34).

FIG.1.

Transcription and localization of lef-6 in AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells. (A) A schematic representation of the AcMNPV lef-6 locus shows the relative positions and orientations of the iap1, lef-6, and orf29 ORFs. Primers used for mapping the lef-6 transcripts by 5′ and 3′ RACE analyses are shown as short arrows below the lef-6 ORF (GSP1, GSP2, and 3′ RACE), and the position of the cRNA probe used for Northern blot analysis is shown as a long arrow (Probe: 343 nt). Relative positions of lef-6 and iap1 RNAs are indicated as dashed lines above the ORFs. (B) Sequences derived from 5′ and 3′ RACE analyses are shown below AcMNPV genomic sequences (AcMNPV). A large arrow (labeled 23,397) indicates the position of the 5′ end mapped by 5′ RACE, and single underlined nucleotides represent 5′ ends mapped in a previous study (34). (C) Northern blot analysis of lef-6 transcription in AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells. Numbers above each lane indicate the time (hours) p.i. when RNAs were isolated (Sf9, mock-infected Sf9 cells). The sizes (kb) of le-6 and iap1 RNAs are indicated on the right. (D to G) Localization of LEF-6 in AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells. LEF-6 was localized by immunofluorescent staining of AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells by using an anti-LEF-6 antiserum as described in Materials and Methods. Left panels show phase-contrast images of uninfected Sf9 cells (D) or AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells (F) at 18 h p.i. Panels on the right show epifluorescence micrographs of uninfected (E) or AcMNPV-infected (G) Sf9 cells, and arrowheads indicate dense areas of infected cell nuclei with intense staining (in panel G).

Immunolocalization of LEF-6 in infected cells.

The lef-6 ORF encodes a predicted protein of 173 amino acids, with a predicted molecular mass of ca. 20.4 kDa. For the current study, we generated an anti-LEF-6 antiserum and then affinity-purified anti-LEF-6 antibodies. By using purified anti-LEF-6 antibodies, we examined the cellular localization of the LEF-6 protein by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1D to G). Although uninfected Sf9 cells showed some nonspecific general background staining, the most intense fluorescence from anti-LEF-6 antibodies was detected within dense areas of the nucleus in AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells (Fig. 1G). Less-intense fluorescence also appeared to be located throughout the nucleus and within the cytoplasm of the infected cells.

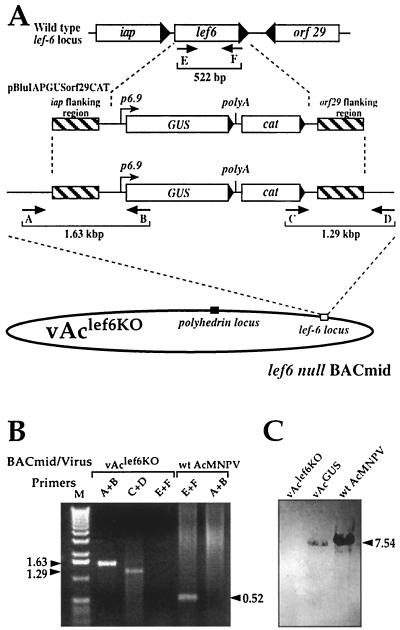

Generation of a lef-6-null BACmid.

To examine the role of lef-6 in the context of the AcMNPV genome and over the course of the viral infection cycle, we generated an infectious BACmid containing a knockout in the lef-6 gene. To accomplish this, we constructed a transfer vector (pBluIAPGUSorf29CAT) containing the lef-6 locus but with the lef-6 ORF removed and replaced by a p6.9-GUS reporter cassette, and a chloramphenicol resistance gene (cat) cassette for selection of recombinants in E. coli (Fig. 2). We used a previously described method (20a) to generate a lef-6 null BACmid (vAclef6KO) by homologous recombination in E. coli. For this procedure, the linear DNA insert from the above transfer vector plasmid was cotransformed in combination with the commercially available AcMNPV BACmid genome (bMON14272) into E. coli BJ5183 cells. BACmids resulting from recombination and deletion of the lef-6 ORF were selected by growth on medium containing kanamycin and chloramphenicol. After a preliminary screening by PCR, a single cloned BACmid with the lef-6 deletion and with insertion of p6.9-GUS and CAT at the lef-6 locus was selected and named vAclef6KO. Insertion of the p6.9-GUS and CAT cassette and knockout of lef-6 were confirmed by a combination of PCR analysis (Fig. 2B) and Southern blot analysis (Fig. 2C). Primer pairs flanking the junctions of the inserted GUS-CAT cassette at the modified lef-6 locus were used to confirm the predicted insertion of the reporter cassette (Fig. 2B, primers A and B and primers C and D). In addition, the deletion of the lef-6 ORF from vAclef6KO was confirmed by PCR analysis (Fig. 2B, primers E and F) and by Southern blot analysis with a labeled probe from within the lef-6 ORF (Fig. 2C). Although the lef-6 ORF was detected on Southern blots of wt AcMNPV and a control BACmid (vAc64−/+GUS), the lef-6 ORF was not detected from vAclef6KO BACmid DNA.

FIG. 2.

Construction of a lef-6-null virus. (A) The strategy for construction of a lef-6-null BACmid containing a deletion of the AcMNPV lef-6 gene is shown in the diagram. The structure of the lef-6 locus is shown above that of the linear DNA fragment excised from transfer vector (pBluIAPGUSorf29CAT) and used for recombination in E. coli. In pBluIAPGUSorf29CAT, the lef-6 ORF was excised and replaced with a p6.9 promoter-driven GUS gene plus a chloramphenicol resistance gene cassette (cat). The structure of the resulting lef-6 locus in BACmid vAclef6KO is shown in the lower portion of the diagram. The positions of primers used for PCR analysis of the resulting AcMNPV BACmid (vAclef6KO) are indicated by small arrows, and the locations and sizes of predicted PCR products are indicated by brackets below the diagrams. (B) The results of PCR analysis of the lef-6 locus of the lef-6-null BACmid (vAclef6KO) are shown on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. Templates (vAclef6KO and wild-type AcMNPV) and primer pairs (A+B, C+D, and E+F) are shown above the lanes, and the sizes of PCR amplification products (in kilobase pairs) are indicated on the right and left. M, marker DNAs. Primer pairs (A+B, C+D, and E+F) correspond to those shown in panel A. (C) Southern blot analysis was used to confirm the absence of lef-6 in the lef-6-null BACmid (vAclef6KO). For hybridization analysis, a lef-6-specific DNA probe was hybridized to XhoI-digested virus or the BACmid DNAs indicated above each lane.

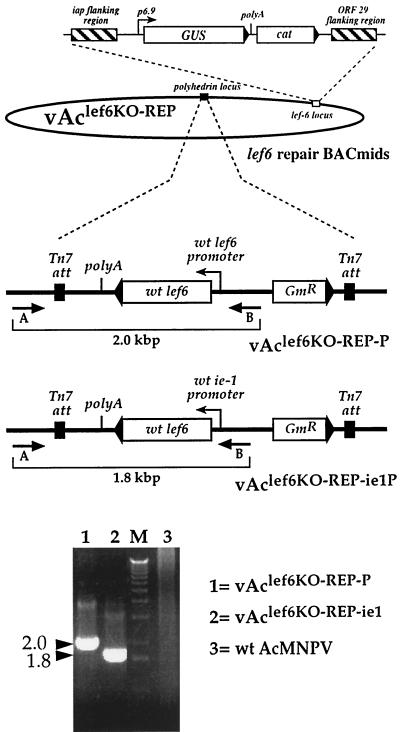

For confirmation of the phenotype resulting from the lef-6 knockout, two “repair” BACmids were constructed from vAclef6KO by reinserting the lef-6 gene under the control of either the wild-type lef-6 promoter or the AcMNPV ie-1 promoter. Each lef-6 construct was inserted into the polyhedrin locus of vAclef6KO by transposition by using the BAC-to-BAC system (Fig. 3). Reinsertion of each lef-6 cassette was confirmed by PCR analysis with a primer pair that confirmed the transposition event (Fig. 3, primers A and B). The repair BACmids were named vAclef6KO-REP-P or vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P.

FIG. 3.

Construction and analysis of lef6 repair viruses. Two lef-6 gene constructs were inserted into the polyhedrin locus of the lef-6-null BACmid (vAclef6KO) to generate repair BACmids vAclef6KO-REP-P and vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P. The structures of the inserted lef-6 constructs are shown, and the promoter (wild-type lef-6 or wild-type ie-1) used to drive lef-6 expression is indicated along with the gentamicin resistance gene (Gmr), and transposon Tn7 attachment sites (Tn7 att). The relative locations of PCR primers used for analysis of the polyhedrin locus are indicated below each construct (indicated by A and B), and the relative sizes of the predicted PCR amplification products are indicated below with brackets. The results of PCR analysis are shown on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel below. Template DNAs are indicated on the right of the gel, and the sizes of the PCR products (in kilobase pairs) are indicated on the left.

Viral replication in Sf9 cells.

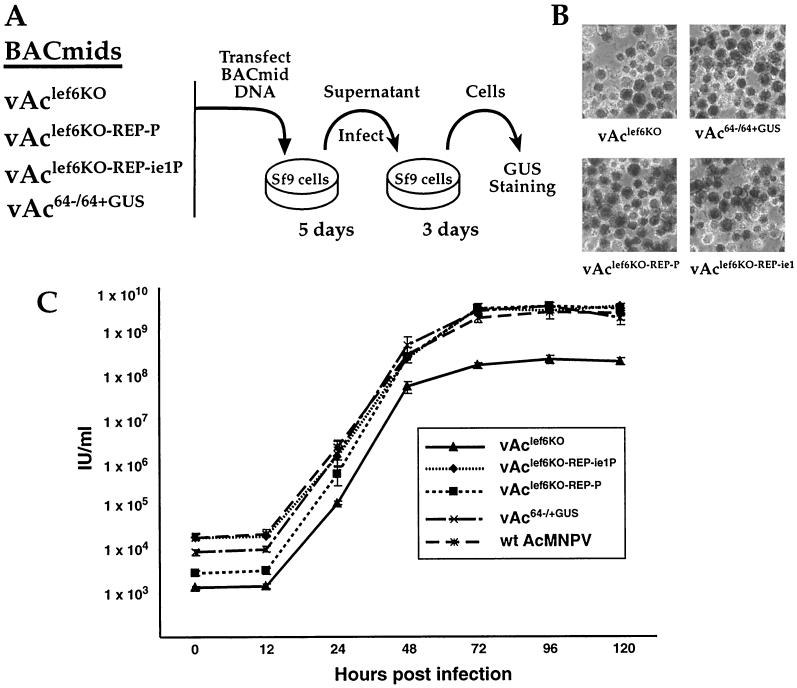

To determine whether the lef-6 gene was essential for viral replication, Sf9 cells were transfected with either vAclef6KO, vAclef6KO-REP-P, vAcBAClef6-REP-ie1P, or vAc64−/+GUS BACmid, and then a transfection-infection assay was performed as indicated in Fig. 4A. BACmid vAc64−/+GUS, which was used as a control BACmid, is derived from BACmid bMON14272 but contains a wild-type lef-6 locus and a p6.9 promoter GUS cassette in the polyhedrin locus. After transfection, Sf9 cells were examined for evidence of virus infection and propagation (Fig. 4A). At 5 days posttransfection, supernatants were removed from transfected cells and added to a second group of freshly plated Sf9 cells; those cells were then incubated for 3 days to detect infectious virus generated from cells transfected with each BACmid. At each step, cells were examined for visible signs of cytopathic effects and stained with X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronic acid) to detect expression of GUS from the late gene reporter construct (p6.9-GUS). Positive GUS staining and cytopathic effects were observed from Sf9 cells transfected with the lef-6 knockout BACmid, vAclef6KO, and also from cells incubated with the supernatant from that transfection (Fig. 4B). A similar result was observed for Sf9 cells transfected with the vAclef6KO-REP-P, vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P, and vAc64−/+GUS BACmids (Fig. 4B). Thus, initial transfection-infection experiments indicated that the lef-6 gene was not essential for viral replication in Sf9 cells.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of viral replication by a lef-6-null virus. (A) A transfection-infection assay was used to examine lef-6-null BACmids for viral replication in Sf9 cells. BACmid DNAs from the indicated constructs were used to transfect Sf9 cells, and cells were incubated for 5 days. Supernatants from transfected cells were transferred to a second group of Sf9 cells, which were subsequently incubated for 3 days and then stained for GUS expression from the p6.9 late promoter-GUS reporter. (B) The results of GUS staining of infected cells are shown in the panels on the right. (C) Virus growth curves were generated to measure virus production from Sf9 cells infected with viruses derived from each of the BACmid constructs or wild-type AcMNPV. Infectious budded virions were prepared from the BACmids vAclef6KO, vAclef6KO-REP-P, vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P, or vAc64−/+GUS or from wild-type AcMNPV. Infections were performed in triplicate at an MOI of 5, and supernatants were collected and assayed for production of infectious virus by TCID50.

To measure the effect of the lef-6 knockout on viral replication in Sf9 cells, a one-step growth curve experiment was performed (Fig. 4C). For growth curve experiments, lef-6 knockout (vAclef6KO), repair (vAclef6KO-REP-P and vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P), and control (wild-type AcMNPV and vAc64−/+GUS) viruses were amplified, and the titers of budded virus preparations were determined in Sf9 cells. These virus preparations were used to infect Sf9 cells at an MOI of 5, and infectious virus production was measured at various times p.i. Virus production from the lef-6-null virus (vAclef6KO) was reduced compared to that from either the lef-6 repair viruses (vAclef6KO-REP-P and vAclef6KO-REP-i.e.1P) or from other control viruses (vAc64−/+GUS and wild-type AcMNPV). Production of infectious virus from the lef-6-null virus appeared to lag behind that of control viruses, and the total virus yield was approximately 1 log lower than that from control and repair viruses. Thus, while lef-6 was not required for virus replication, both the timing of virus production and the yield of infectious virus were affected by the lef-6 knockout. These effects were rescued by reinsertion of the lef-6 gene into the polyhedrin locus of the lef-6-null virus, indicating that these effects were not due to secondary mutations or from local cis-acting elements.

Analysis of DNA replication.

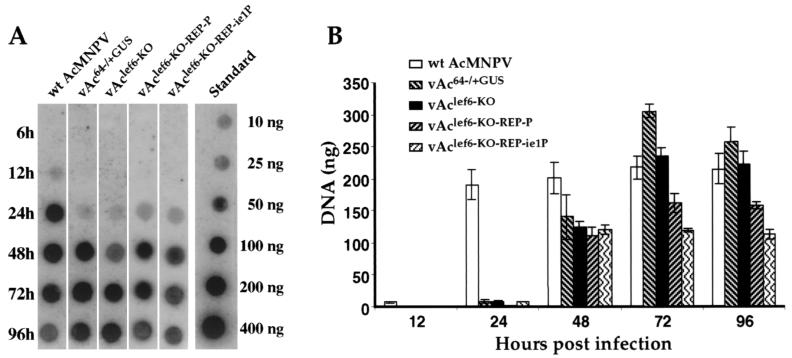

To determine whether viral DNA replication in AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells was affected by the lef-6 knockout, we examined DNA replication in cells infected with the lef-6-null virus (Fig. 5). Cells were infected with either the lef-6-null virus (vAclef6KO), wild-type AcMNPV, or control viruses (vAc64−/+GUS, vAclef6KO-REP-P, and vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P), and DNA was isolated from infected cells at various times p.i. To detect replication of the viral genome, the wild-type AcMNPV genome was labeled and used as a hybridization probe for Southern dot blot analysis. DNA replication was observed from the lef-6-null virus (vAclef6KO), as well as from all control and wild-type viruses (Fig. 5). DNA replication was first detected from wild-type AcMNPV as a lower level signal at 12 h p.i. For control and repair viruses, DNA replication was first detected at 24 h p.i but was abundant by 48 h p.i. Comparisons of wild-type AcMNPV to BACmid-derived viruses suggest that DNA replication is delayed in the BACmid-derived viruses. Although the cause of this result is unclear, the effect was consistent. Similar to the other BACmid-derived viruses, DNA replication from the lef6-null virus was first detected at 24 h p.i. but was abundant by 48 h p.i. Figure 5B shows a quantitative analysis of DNA replication that incorporates the results of replicate infections and DNA dot blots. The same trends are observed in these analyses. Most importantly, DNA replication was observed in viruses with a deletion of the lef-6 gene, and the timing and magnitude of DNA replication did not appear to differ substantially from control and repair viruses derived from BACmids. Thus, lef-6 does not appear to affect viral DNA replication, and this finding is consistent with prior results from transient DNA replication assays (17, 24).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of viral DNA replication in Sf9 cells infected with lef-6-null and control viruses. (A) Sf9 cells were infected with viruses derived from either wild-type AcMNPV, control BACmid (vAc64−/+GUS), lef-6-null BACmid (vAclef6KO), or lef-6 repair BACmids (vAclef6KO-REP-P or vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P), and total cellular DNAs were isolated at various times posttransfection (6 to 96 h) and examined by Southern dot blot hybridization. Total AcMNPV DNA was labeled with [32P]dATP as a hybridization probe. A standard curve of AcMNPV DNA is shown on the right (10 to 400 ng of AcMNPV DNA). (B) Quantitative analysis of viral DNA replication by Southern dot blot analysis. Three replicates of each virus infection and time point were examined as in panel A, and DNA was quantified by phosphorimager analysis. Bars represent the average of three dot blot samples, and error bars represent the standard deviation.

Analysis of AcMNPV transcription.

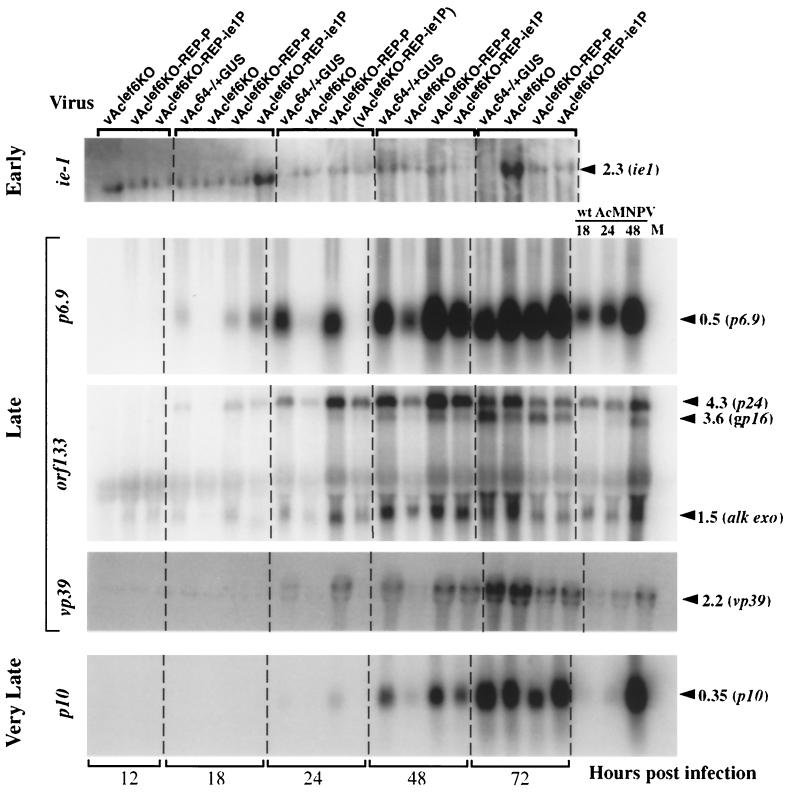

To examine the effect of the lef-6 knockout on AcMNPV transcription in the context of an AcMNPV infection, gene-specific cRNA probes representing early, late, and very late genes were used for Northern blot analysis of transcripts at various times p.i. An ie-1 probe was used as a control to detect and monitor early transcription, whereas p6.9, vp39, and orf133 gene-specific probes were used to examine late transcription. Since orf133 is the 3′ terminal ORF in a region containing five ORFs that are transcribed from separate late promoters but are 3′ coterminal (30), the orf133 probe hybridizes to late transcripts from p24 capsid, gp16, pp34-pep, orf132, and alk-exo. A p10 gene-specific probe was used to examine very late transcription. Sf9 cells were infected with the lef-6-null or control viruses, and RNAs were isolated at various times p.i. and used for Northern blot analysis with the indicated early, late, or very late gene-specific probes (Fig. 6). The lef-6-null virus was compared directly with the two BACmid-derived repair viruses (vAclef6KO-REP-P and vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P) and with the BACmid-derived control virus (vAc64−/+GUS). Transcription of the early genes did not appear to be affected by the lef-6 knockout, since the ie-1 transcript was detected at 12 h p.i. and was present at levels similar to that detected with the two repair viruses expressing the lef-6 gene. Late and very late transcription were both delayed in cells infected with the lef-6-null virus. This is apparent from comparisons of results from late and very late gene-specific probes at 18, 24, and 48 h p.i. At these times, transcripts from these late and very late genes by the lef-6-null virus (vAclef6KO) were significantly reduced (or absent) compared to the control viruses (vAc64−/+GUS, vAclef6KO-REP-P, and vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P) (Fig. 6). Late and very late transcription appeared to be normal in the lef-6 repair viruses (vAclef6KO-REP-P and vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P). While late transcription from the lef-6-null virus was substantially reduced during the period from 18 to 48 h p.i., substantial levels of late and very late transcripts were observed from the lef-6-null virus at 72 h p.i., indicating that late transcription is delayed but not eliminated by the absence of lef-6. This is consistent with our observation that the lef-6 knockout is not a lethal mutation and that substantial amounts of progeny virus were produced from the lef-6-null virus.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of viral early, late, and very late transcripts in lef-6-null and control virus-infected Sf9 cells. Each panel represents Northern blot analysis of early, late, or very late RNAs from cells infected with lef-6-null (vAclef6KO) or control (vAclef6KO-REP-P, vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P, or vAc64−/+GUS) viruses. Sf9 cells were infected at an MOI of 5. At various times p.i. (12, 18, 24, 48, or 72 h), total RNAs were isolated and used for Northern blot analysis with early (ie-1), late (p6.9, orf133, and vp39), or very late (p10) gene-specific probes. Viruses used for infections are indicated at the top of the lanes, and gene-specific probes are indicated on the left. The sizes of expected RNAs from each gene-specific probe are indicated in kilobases on the right. For comparison, RNAs isolated from wild-type AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells at 18, 24, and 48 h p.i. are shown on the right. M, mock-infected cells. (Note that the 24-h-p.i. time point for vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P is missing RNA samples on blots for p6.9, vp39, and p10. The sample name is therefore indicated in parentheses above.)

Analysis of a late promoter-reporter.

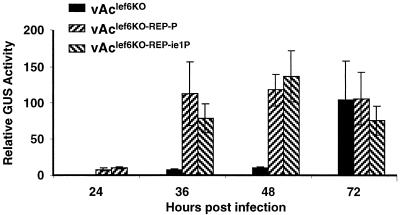

We also examined the effect of the lef-6 knockout on the expression of a p6.9 promoter-driven GUS reporter gene included in the knockout and repair constructs. For these experiments, Sf9 cells were infected with either the lef-6-null virus (vAclef6KO) or one of the repair viruses (vAclef6KO-REP-P or vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P). Figure 7 shows that by 36 to 48 h p.i. GUS reporter expression from the p6.9 promoter is substantial in cells infected with the repair viruses but was detected only at low levels in cells infected with the lef-6-null virus. By 72 h p.i., GUS expression from cells infected with the lef-6-null virus had increased substantially and total GUS reporter levels were not significantly different from cells infected with the repair viruses. These results from the p6.9-GUS reporter (Fig. 7) are consistent with those from Northern blot analyses of transcripts from several late genes (Fig. 6) and further support the conclusion that late transcription is delayed in the lef-6-null virus.

FIG. 7.

Late p6.9 promoter-reporter analysis in lef-6-null and control virus-infected cells. Temporal expression of a GUS reporter gene under the control of a p6.9 late promoter was measured from extracts of Sf9 cells infected with either the lef-6-null (vAclef6KO) or repair (vAclef6KO-REP-P and vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P) viruses. GUS activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Times p.i. are indicated below the x axis. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three independent infections.

DISCUSSION

The lef-6 gene was originally identified in transient-expression assays as necessary for optimal transcription from an AcMNPV late promoter. In the present study, we examined the expression of lef-6 and its cellular localization during the AcMNPV infection cycle. We also generated and used a lef-6 knockout virus to study the role of LEF-6 in viral late gene transcription. The transcription of the lef-6 gene was previously examined (34), and we confirmed here the general results presented in that earlier study. Minor differences in the mapped 5′ and 3′ ends were observed. Such differences could result from artifacts inherent in the techniques utilized or, alternatively, may represent heterogeneity in mRNA ends. lef-6 mRNAs were detected from 4 to 48 h p.i. and were most abundant at 12 and 24 h p.i. A previous study showed that lef-6 was transcribed in the presence of either the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide or the DNA replication inhibitor aphidicolin (34). We found, by immunofluorescent microscopy, that LEF-6 was localized to the nuclei of infected cells. Thus, the timing and circumstances of lef-6 expression, and its cellular localization, are consistent with its classification as an early gene and its potential role in modulating or regulating late transcription.

To examine the role of lef-6 during the infection cycle of AcMNPV in Sf9 cells, we initially attempted to generate a lef-6 knockout virus by the traditional method of recombination in infected Sf9 cells. We were unable to isolate a knockout by that method, and our result was similar to that reported by Gomi et al. (9), who were also unable to isolate a virus containing a knockout in the BmNPV lef-6 gene by that method. To generate a lef-6 knockout for the current study, we used homologous recombination with an infectious AcMNPV BACmid propagated in E. coli, as described elsewhere (4, 20a). Since the AcMNPV genome is propagated and modified in an E. coli host, in the absence of normal selection pressures there exists the possibility that second site mutations may arise and that these mutations may confuse the interpretation of the phenotype of the resulting knockout virus. To confirm that the observed phenotype resulted from the deletion of the lef-6 gene, we used the lef-6 knockout BACmid (vAclef6KO) to generate two repair viruses (vAclef6KO-REP-P or vAclef6KO-REP-ie1P). In the repair viruses, lef-6 expression was restored by inserting the lef-6 gene into the polyhedrin locus. In both cases, the observed mutant phenotype from the lef-6 knockout was rescued by reinserting the lef-6 gene, thus confirming that the observed phenotype resulted from the lef-6 knockout and not from a second site mutation or from local cis-acting effects.

After transfection of the lef-6-null BACmid into Sf9 cells, we were able to generate a lef-6-null virus that propagated in cell culture, thus indicating that the lef-6 gene was not essential for virus replication in Sf9 cells. Further analysis showed that lef-6 was not required for either viral DNA replication or late transcription. However, late transcription was substantially delayed in Sf9 cells infected with the lef-6-null virus; the production of infectious virus was also delayed, and the total viral yield was reduced substantially. Thus, lef-6 does not appear to play an essential role in AcMNPV infection in Sf9 cells, but its presence accelerated the infection cycle and increased virus yields.

No significant sequence similarities have been reported between LEF-6 and nonbaculovirus proteins with known functions. Although it was originally reported that LEF-6 had some very limited sequence similarity to the 19-kDa subunit of an RNA polymerase from vaccinia virus (34), it is unclear whether the very low degree of similarity is significant. Within the family Baculoviridae, the LEF-6 protein is moderately conserved among a number of nucleopolyhedroviruses (AcMNPV, BmNPV, Epiphyas postvittana NPV, Orgyia pseudotsugata MNPV, Spodoptera exigua MNPV, Spodoptera litura NPV, Helicoverpa armigera NPV, Lymantria dispar MNPV, and Trichoplusia ni SNPV). The highest level of conservation appears to be in the N-terminal 68 to 70 amino acids, and an acidic C-terminal domain also appears to be conserved. Except for the BmNPV and AcMNPV genes (which have only a few minor differences), conservation of LEF-6 proteins within the above NPVs is moderate, with ca. 17 to 56% overall identity. Conservation of LEF-6 proteins is very low between NPVs and granuloviruses (GVs), as previously reported (14, 26). However, the putative LEF-6 homologs (Px60 from the Plutella xylostella GV, Xc88 from Xestia c-nigrum GV, and Cp80 from Cydia pomonella GV) from several GVs that have been sequenced are moderately conserved among the GVs, with amino acid sequence identities of ca. 33 to 42%.

Our studies revealed no significant effect of lef-6 on viral DNA replication but a substantial effect on the timing of late gene transcription and virion yield. These results are consistent with the results of prior transient late expression and DNA replication assays, in which lef-6 did not affect transient origin-dependent DNA replication (17, 24). The observed delay in late transcription, however, was not detected by transient assay.

While all late genes appear to share certain general features of late gene regulation, all late genes do not seem to be regulated identically. For example, it seems clear that some late genes, such as p6.9, are transcribed at higher levels than other late genes. Prior studies have shown that the recognition of late promoters, and the regulation of late promoter strength are modulated by sequences flanking the conserved TAAG sequence at the transcription start site (8, 29). These studies show that the TAAG sequence alone is not sufficient for late promoter recognition and that mutations in flanking regions can result in a graded effect on transcription. It is also possible that these flanking sequences could also affect the temporal appearance of late transcripts. Thus, differences in late promoter recognition, temporal modulation of late promoter activation, and late promoter strength may be modulated by sequences flanking the TAAG motifs and the proteins from the assembled late polymerase complex with which they probably interact. In the present study of a lef-6-null virus, we observed one potentially important differential effect of lef-6 on late gene regulation. This effect was observed by comparing the levels of p6.9 and p24 (4.3-kb) transcripts at 24 h p.i. (Fig. 6). In cells infected with the lef-6-null virus (vAclef6KO), the p6.9 transcript appears to be almost completely absent at 24 h p.i., whereas the p24 transcript can be readily detected at that time. While both p6.9 and p24 transcription appeared to be significantly affected by the lef-6 knockout, the effect on these two promoters also appears to differ. A more detailed analysis of these promoters and the effects of lef-6 on them will be necessary to determine whether lef-6 has differential effects on different late promoters. Because these initial studies have examined the steady-state levels of late transcripts, we also cannot rule out the possibility that LEF-6 might play a role in differential stabilization of specific late transcripts. The generation of knockouts in this and other lef genes, combined with more quantitative and more comprehensive examinations of late promoter activities, should permit the identification of specific regulatory proteins that modulate differential expression of late genes and perhaps progression into the very late phase of transcription.

Acknowledgments

We thank Oliver Lung for providing BACmid control vAc64−/+GUS and for advice during the course of these studies. We also thank Brian Federici and Dennis Bideshi for providing E. coli BJ5183 and Gretchen Hoffmann for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (99-35302-7952) and the National Institutes of Health (AI33657).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahrens, C. H., D. J. Leisy, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1996. Baculovirus DNA replication, p. 855-872. In M. L. DePamphilis (ed.), DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 2.Ayres, M. D., S. C. Howard, J. Kuzio, M. Lopez-Ferber, and R. D. Possee. 1994. The complete DNA sequence of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 202:586-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baklanov, M. M., L. N. Golikova, and E. G. Malygin. 1996. Effect on DNA transcription of nucleotide sequences upstream to T7 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:3659-3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bideshi, D. K., and B. A. Federici. 2000. The Trichoplusia ni granulovirus helicase is unable to support replication of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus in cells and larvae of T. ni. J. Gen. Virol. 81: 1593-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blissard, G. W., R. L. Quant-Russell, G. F. Rohrmann, and G. S. Beaudreau. 1989. Nucleotide sequence, transcriptional mapping, and temporal expression of the gene encoding P39, a major structural protein of the multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Orgyia pseudotsugata. Virology 168:354-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards, R. A., L. H. Keller, and D. M. Schifferli. 1998. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friesen, P. D. 1997. Regulation of baculovirus early gene expression, p. 141-166. In L. K. Miller (ed.), The baculoviruses. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 8.Garrity, D. B., M.-J. Chang, and G. W. Blissard. 1997. Late promoter selection in the baculovirus gp64 envelope fusion protein gene. Virology 231:167-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomi, S., C. E. Zhou, W. Yih, K. Majima, and S. Maeda. 1997. Deletion analysis of four of eighteen late gene expression factor gene homologues of the baculovirus, BmNPV. Virology 230:35-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross, C. H., and S. Shuman. 1998. RNA 5′-triphosphatase, nucleoside triphosphatase, and guanylyltransferase activities of baculovirus LEF-4 protein. J. Virol. 72:10020-10028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grula, M. A., P. L. Buller, and R. F. Weaver. 1981. Alpha-amanitin-resistant viral RNA synthesis in nuclei isolated from nuclear polyhedrosis virus-infected Heliothis zea larvae and Spodoptera frugiperda cells. J. Virol. 38:916-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarino, L. A., J. Jin, and W. Dong. 1998. Guanylyltransferase activity of the LEF-4 subunit of baculovirus RNA polymerase. J. Virol. 72:10003-10010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarino, L. A., B. Xu, J. Jin, and W. Dong. 1998. A virus-encoded RNA polymerase purified from baculovirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 72:7985-7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashimoto, Y., T. Hayakawa, Y. Ueno, T. Fujita, Y. Sano, and T. Matsumoto. 2000. Sequence analysis of the Plutella xylostella granulovirus genome. Virology 275:358-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huh, N. E., and R. F. Weaver. 1990. Categorizing some early and late transcripts directed by the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 71:2195-2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin, J., W. Dong, and L. A. Guarino. 1998. The LEF-4 subunit of baculovirus RNA polymerase has RNA 5′-triphosphatase and ATPase activities. J. Virol. 72:10011-10019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kool, M., C. H. Ahrens, R. W. Goldbach, G. F. Rohrmann, and J. M. Vlak. 1994. Identification of genes involved in DNA replication of the Autographa californica baculovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11212-11216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, L., S. H. Harwood, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1999. Identification of additional genes that influence baculovirus late gene expression. Virology 255:9-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin, G., G. Li, R. R. Granados, and G. W. Blissard. 2001. Stable cell lines expressing baculovirus P35: resistance to apoptosis and nutrient stress, and increased glycoprotein secretion. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 37:293-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin, G., J. M. Slack, and G. W. Blissard. 2001. Expression and localization of LEF-11 in Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus infected Sf9 cells. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2289-2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Lin, G., and G. W. Blissard. 2002. Analysis of an Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus lef-11 knockout virus: LEF-11 is essential for viral DNA replication. J. Virol. 76:2770-2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu, A., P. J. Krell, J. M. Vlak, and G. R. Rohrmann. 1997. Baculovirus DNA replication, p. 171-192. In L. K. Miller (ed.), The baculoviruses. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 22.Lu, A., and L. K. Miller. 1994. Identification of three late expression factor genes within the 33.8- to 43.4-map-unit region of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 68:6710-6718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu, A., and L. K. Miller. 1997. Regulation of baculovirus late and very late gene expression, p. 193-216. In L. K. Miller (ed.), The baculoviruses. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 24.Lu, A., and L. K. Miller. 1995. The roles of eighteen baculovirus late expression factor genes in transcription and DNA replication. J. Virol. 69:975-982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luckow, V. A., S. C. Lee, G. F. Barry, and P. O. Olins. 1993. Efficient generation of infectious recombinant baculoviruses by site-specific transposon-mediated insertion of foreign genes into a baculovirus genome propagated in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 67:4566-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Lung, O., M. Westenberg, J. M. Vlak, D. Zuidema, and G. W. Blissard. 2002. Pseudotyping Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus: (AcMNPV): F proteins from group II NPVs are functionally analogous to AcMNPV GP64. J. Virol. 76:5729-5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luque, T., R. Finch, N. Crook, D. R. O'Reilly, and D. Winstanley. 2001. The complete sequence of the Cydia pomonella granulovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2531-2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Martins, A., and S. Shuman. 2001. Mutational analysis of baculovirus capping enzyme Lef4 delineates an autonomous triphosphatase domain and structural determinants of divalent cation specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45522-45529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris, T. D., and L. K. Miller. 1994. Mutational analysis of a baculovirus major late promoter. Gene 140:147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oellig, C., B. Happ, T. Mueller, and W. Doerfler. 1987. Overlapping sets of viral RNA species reflect the array of polypeptides in the EcoRI J. and N fragments, map positions 81.2 to 85.0 of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus genome. J. Virol. 61:3048-3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oomens, A. G. P., and G. W. Blissard. 1999. Requirement for GP64 to drive efficient budding of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 254:297-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Reilly, D. R., L. K. Miller, and V. A. Luckow. 1992. Baculovirus expression vectors: a laboratory manual. W. H. Freeman and Co., New York, N.Y.

- 33.Passarelli, A. L., and L. K. Miller. 1993. Identification and characterization of lef-1, a baculovirus gene involved in late and very late gene expression. J. Virol. 67:3481-3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Passarelli, A. L., and L. K. Miller. 1994. Identification and transcriptional regulation of the baculovirus lef-6 gene. J. Virol. 68:4458-4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Passarelli, A. L., J. W. Todd, and L. K. Miller. 1994. A baculovirus gene involved in late gene expression predicts a large polypeptide with a conserved motif of RNA polymerases. J. Virol. 68:4673-4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prikhod'ko, E. A., A. Lu, J. A. Wilson, and L. K. Miller. 1999. In vivo and in vitro analysis of baculovirus ie-2 mutants. J. Virol. 73:2460-2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rapp, J. C., J. A. Wilson, and L. K. Miller. 1998. Nineteen baculovirus open reading frames, including LEF-12, support late gene expression. J. Virol. 72:10197-10206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rice, W. C., and L. K. Miller. 1986. Baculovirus transcription in the presence of inhibitors and in nonpermissive Drosophila cells. Virus Res. 6:155-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todd, J. W., A. L. Passarelli, and L. K. Miller. 1995. Eighteen baculovirus genes, including lef-11, p35, 39K, and p47, support late gene expression. J. Virol. 69:968-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]