Abstract

Elements of local tertiary structure in RNA molecules are important in understanding structure–function relationships. The loop E motif, first identified in several eukaryotic RNAs at functional sites which share an exceptional propensity for UV crosslinking between specific bases, was subsequently shown to have a characteristic tertiary structure. Common sequences and secondary structures have allowed other examples of the E-loop motif to be recognized in a number of RNAs at sites of protein binding or other biological function. We would like to know if more elements of local tertiary structure, in addition to the E-loop, can be identified by such common features. The highly structured circular RNA genome of the hepatitis D virus (HDV) provides an ideal test molecule because it has extensive internal structure, a UV-crosslinkable tertiary element, and specific sites for functional interactions with proteins including host PKR. We have now found a UV-crosslinkable element of local tertiary structure in antigenomic HDV RNA which, although differing from the E-loop, has a very similar pattern of sequence and secondary structure to the UV-crosslinkable element found in the genomic strand. Despite the fact that the two structures map close to one another, the sequences comprising them are not the templates for each other. Instead, the template regions for each element are additional sites for potential higher order structure on their respective complementary strands. This wealth of recurring sequences interspersed with base-paired stems provides a context to examine other RNA species for such features and their correlations with biological function.

Keywords: HDV RNA, higher order RNA folding, mapping RNA tertiary elements, RNA:protein binding, RNA structure

INTRODUCTION

Preexisting elements of local tertiary structure have been identified by UV crosslinking in a wide variety of RNAs including tRNA (Ninio et al. 1969; Yaniv et al. 1969), Escherichia coli 16S rRNA (Zwieb et al. 1978; Atmajda et al. 1985), eukaryotic 5S rRNA and plant viroid RNA (Branch et al. 1985a), SRP RNA (Zwieb and Schuler 1989), the self-splicing group I intron from Tetrahymena (Downs and Cech 1990, 1996) and the hairpin ribozyme (Butcher and Burke 1994; Hampel and Burke 2001). In addition, the ability of UV exposure to introduce covalent RNA–RNA bonds at specific RNA sites has located specific interactions between tRNA and 16S rRNA (Prince et al. 1982), and between the Ml RNA subunit of E. coli RNase P and its substrate (Guerrier-Takada et al. 1989).

The success of the UV crosslinking technique in locating preexisting RNA structural elements was confirmed by studies on the internal loop (loop E) of eukaryotic 5S rRNA. This element was discovered (Branch et al. 1985a) as an entity that undergoes UV crosslinking at a site later shown by NMR spectroscopy to exhibit several non-Watson–Crick interactions (Wimberly et al. 1993). This NMR analysis set a pattern for such studies by providing the first concrete physical evidence for a specific preexisting higher order structure in a UV-sensitive RNA element in a molecule other than tRNA, and suggested a role for it in the binding of transcription factor TFIIIA to 5S rRNA during end-product inhibition of transcription (Romaniuk et al. 1987; Allison et al. 1991). Further, the E-loop structural motif and related elements have subsequently been found in protein-binding domains of other RNAs, including the sarcin/ricin loop of ribosomal RNA (Correll et al. 1998; Leontis and Westhof 1998) and the internal ribosome entry site domain of hepatitis C virus (Klinck et al. 2000; Lukavsky et al. 2000; Lyons et al. 2001). Results from several sources suggest that the search for potential sites containing E-loop structural motifs can be assisted by seeking certain sequence and base-pairing combinations (e.g., Klinck et al. 2000).

Although the validity of UV crosslinking to screen RNA molecules for tertiary elements with potential biological significance is now unquestioned, we would like to know if a general process for identifying specific sequences and secondary structures within such elements can strengthen this approach. If specific seqences and/or base-paired elements are found in the vicinity of tertiary structure sites, they would enhance our ability to identify additional structural domains, whether or not they are capable of undergoing UV crosslinking. The highly structured RNA genome of the hepatitis D virus (HDV, or the delta agent) is an ideal test molecule for studying this idea. We already know that the genomic strand of HDV contains a tertiary structural element that undergoes UV-crosslinking between two bases at a specific site (Branch et al. 1989a, 1990a, 1990b).

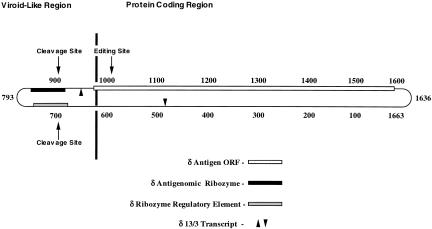

Figure 1 ▶ is a schematic diagram of the HDV RNA genome. Both strands utilize the same map and numbering system: For genomic RNA, the 5′-to-3′ direction is clockwise, whereas for antigenomic RNA, the 5′-to-3′ direction is counterclockwise. As pointed out earlier (Branch et al. 1989a, Robertson 1992), the HDV RNA genome is divided into a highly conserved, noncoding “viroidlike” region, where replication functions are grouped, and a less conserved “protein coding region” that specifies the HDV antigen, a viral structural protein. The mRNA for the HDV antigen is part of the antigenomic strand, covering the region approximately between bases 1600 (amino terminus) and 1000 (carboxy terminus). The mRNA for HDV antigen undergoes RNA editing in vivo and in vitro, at a site shown in Figure 1 ▶. In the viroidlike region of the HDV antigenomic strand, the indicated domain surrounding residue 900 comprises the ribozyme element that produces mRNA and cleaves multimeric replication intermediates to unit-length strands during HDV replication. A domain surrounding residue 700 is involved in regulating the action of the HDV antigenomic ribozyme (Sharmeen et al. 1988).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of the HDV genome. The collapsed rod structure with the numbering system proposed by Wang et al. (1986) is depicted. For genomic RNA, the 5′ direction is clockwise; whereas for antigenomic RNA, the 5′-to-3′ direction is counterclockwise. The highly conserved “Viroid-Like Region” and the less well-conserved “Protein Coding Region,” first proposed by Branch et al. (1989a), are shown separated by a heavy vertical line. Also shown are the open reading frame for the HDV antigen, a structural protein encoded by the antigenomic strand (“δ Antigen ORF”—unshaded box); the sequence comprising the antigenomic ribozyme (“δ antigenomic ribozyme”—filled box) and its cut site between residues 900 and 901 (“Cleavage Site” with downward pointing arrow); the region shown by Sharmeen et al. (1988) to influence the HDV antigenomic ribozyme activity (“δ Ribozyme Regulatory Element”—gray box); the cut site for the genomic ribozyme between residues 685 and 686 (“Cleavage Site”with upward pointing arrow); the boundaries of the 13/3 RNA transcript covering residues 482–963 (“δ 13/3 Transcript”—arrowheads); and the position at antigenomic residue A1012 that undergoes RNA editing (“Editing Site” with downward pointing arrow).

We know that the UV-crosslinkable element of local tertiary structure in the HDV genomic strand maps just to the left (Fig. 1 ▶) of the ribozyme cleavage site at base 685 in the collapsed rod structure (Branch et al. 1990a), and that it helps to form the binding site for PKR (Circle et al. 1997), a cellular protein kinase that contains two copies of the double-stranded RNA-binding motif (dsRBM; Green and Mathews 1992). The HDV antigen protein is phosphorylated in vivo during viral infection, and recent studies indicate a role for PKR in this process (Yeh et al. 1996; Bichko et al. 1997; Chen et al. 2002). The HDV antigenomic strand has a ribozyme element located across from the genomic ribozyme (Fig. 1 ▶), is known to bind PKR (Robertson et al. 1996), and is also known to be edited (Polson et al. 1996; Sato et al. 2001) by an adenosine deaminase activated by RNA (ADAR), another dsRBM-containing cellular protein (Melcher et al. 1996).

We confirm here that these biological functions of the HDV antigenomic strand are likely to involve local tertiary structure. In particular, we report the presence of a UV-crosslinkable tertiary structural element in the antigenomic strand of HDV with a very similar pattern of sequence and secondary structure to the one on the genomic strand. Surprisingly, despite the fact that the two elements occur very close to one another on the HDV map, the genomic sequences comprising the UV-crosslinkable element are not the templates for the antigenomic element. In fact, the template RNA regions for each element are additional sites for potential higher order structure on their respective complementary strands. The wealth of recurring sequences interspersed with base-paired stems in these structures provides an ideal context in which to seek such elements in other RNAs, and to correlate them with biological function.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Summary of experimental results

Antigenomic HDV has a tertiary structural element in the conserved domain

Our laboratory has worked out techniques for producing specific UV crosslinks in RNA molecules at sites of preexisting local tertiary structure (Branch et al. 1985a, 1989c), isolating the RNAs containing them by altered behavior on polyacrylamide gels, and their specific regions by partial RNase T1 digestion (Branch et al. 1985b, 1989c), and mapping their exact positions in the RNA sequence (Branch et al. 1989a, 1989b, 1989c, 1990a; Lyons et al. 2001). For antigenomic HDV, a transcript containing the conserved domain, spanning residues 482–963 (shown in Fig. 1 ▶) was used to seek a UV-crosslinkable element of local tertiary structure in the HDV antigenomic strand. After UV treatment as before (Branch et al. 1989a, 1989c), two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel analysis revealed a UV-dependent species that ran with a distinctively lower mobility in the second-dimension denaturing gel. Partial RNase T1 digestion and fingerprinting (Branch et al. 1989b, 1989c) showed a single, new oligonucleotide among the specific antigenomic HDV sequences that had undergone UV crosslinking. Sequences were determined by direct means (Barrell 1971; Branch et al. 1989b), with the exact location of the crosslink (linking U701-U889) confirmed by primer extension analysis as before (Lyons et al. 2001). These data are not shown here for the sake of brevity, but are freely available on request.

Recurring features in HDV structural elements

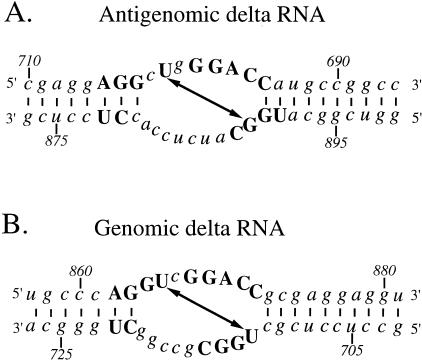

Comparison of UV-sensitive structural elements in HDV

Portions of the antigenomic RNA containing the crosslinked site and flanking sequences, along with the UV-crosslinkable site in the HDV genomic RNA (Branch et al. 1990a), are shown in Figure 2 ▶. After adjusting their orientations to facilitate comparison, they reveal a number of interesting similarities. First, both sites can be drawn as internal loops of between seven and nine unpaired bases on either strand that are flanked by runs of stable Watson–Crick base pairs. The crosslink in both cases occurs at a diagonal across the loop, offset by 6 or 7 nt from the collapsed rod orientation of Wang et al. (1986). Another striking similarity is in the sequence context of the two regions. The bases indicated by upper case letters are found in both sites, with the bases in lower case differing between the two. The upper strands in the immediate vicinity of the crosslinkable U-residue are nearly 90% identical, with the lower strands differing somewhat but still showing homology around the crosslinked base. Given that the antigenomic HDV element of preexisting tertiary structure is so similar to that in the genomic strand—and that the two elements occur so near to one another in the conserved domain of the HDV collapsed rod map—we will first explore how these two elements and the sequences encoding them are positioned and how they might have arisen. We will then comment on their potential roles in ribozyme regulation and host protein binding.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of the antigenomic (A) and genomic (B) HDV UV-sensitive structures. Note that the antigenomic sequence has been inverted with respect to the map in Figure 1 ▶ to facilitate comparison with its genomic counterpart. Both can be drawn as internal loops (which reflect the still unknown higher order folding that must be present, pending X-ray or NMR analysis), flanked by runs of Watson–Crick base pairs. Conserved nucleotides are indicated by upper case letters, whereas nonconserved bases are shown in lower case. The diagonal arrows indicate the bases that undergo UV-crosslinking.

The HDV collapsed rod map shows that each strand has two adjacent domains with potential for forming local tertiary structure

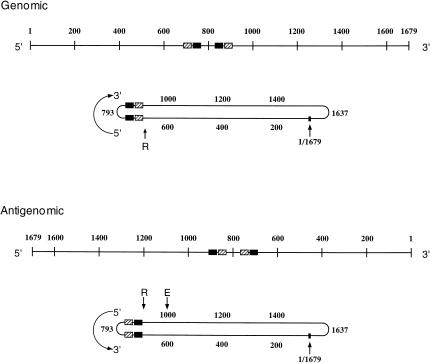

As shown in Figure 3 ▶, the two sequences that comprise the genomic UV-crosslinkable element do not serve as templates for the antigenomic sequences whose UV crosslinking we reported here. We might not have expected this result because, when an RNA molecule (like HDV) has a high degree of internal base pairing, it is possible for two regions directly opposite one another in the base-paired structure of one strand to encode an identical structured element in the complementary RNA strand (e.g., compare the sequences in Fig. 2A ▶, bases 710–703, with Fig. 2B ▶, bases 873–880, and Fig. 2A ▶, 873–880, with Fig. 2B ▶, 710–703). However, the tertiary elements in HDV have little potential base pairing (see Fig. 4 ▶) and do not encode each other.

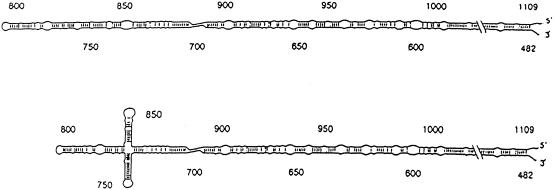

FIGURE 3.

Positions of HDV RNA blocs comprising tertiary structural elements and their templates depicted in both linear and collapsed rod maps. The numbering system of Wang et al. (1986) is employed, and the positions of the first (base 1) and last (base 1679) bases are indicated. The 5′-to-3′ directions are shown in each case. In all maps, the RNA blocs that undergo UV crosslinking in the strand depicted are shown as filled rectangles, whereas templates for such elements in the opposite strand are shown in rectangles hatched with diagonal lines. The “endpoint” bases of the collapsed rod, 793 and 1637, are indicated. The genomic ribozyme cleavage site is depicted by an “R” with an upward-pointing arrow. The antigenomic ribozyme cut site is indicated by an “R” with a downward-pointing arrow; the editing site, by an “E” with a downward-pointing arrow. Upper drawings: The genomic UV-crosslinkable element blocs (filled rectangles) comprise bases 710–735 and 857–875, and the template blocs for the antigenomic UV-crosslinkable element (hatched rectangles) include bases 686–705 and 878–899. Lower drawings: The antigenomic UV-crosslinkable element blocs (filled) are bases 686–705 and 878–899; the templates for the genomic element (hatched) include bases 710–735 and 857–875.

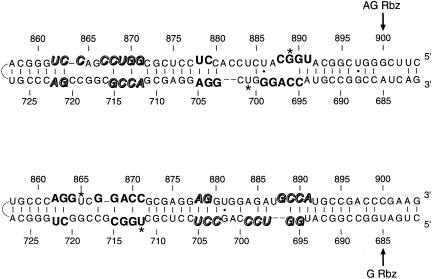

FIGURE 4.

Recurring elements in HDV regions with potential tertiary structure. These drawings each represent a close-up of the critical parts of the collapsed rod maps shown in Figure 3 ▶. The antigenomic region is shown above; the genomic, below. Cleavage points for the antigenomic (“AG Rbz”) and genomic (“G Rbz”) ribozyme activities are indicated, as are 5′ and 3′ termini. The loops shown at the left-hand end of each structure symbolize the nearby “closed end” of the collapsed rod centered at base 793. The bases that undergo UV crosslinking (U701, G889—antigenomic strand; U712, U865—genomic strand) are starred. Potential base pairs (except those involving starred bases) are drawn according to Wang et al. (1986), although their existence as such within the regions of bold or highlighted type is unlikely. Upper drawing: The UV-crosslinkable element reported here is indicated, in the right half of the drawing, by the bold, raised (or lowered) type that highlights its recurring sequences. These blocs correspond to the filled rectangles in the HDV antigenomic map depicted in Figure 3 ▶. In like manner, the template sequences for the genomic UV-sensitive element are depicted, in the left half of the drawing, by italicized, highlighted open type (raised or lowered), which depicts the recurring sequences. These blocs correspond to the hatched rectangles in the Figure 3 ▶ genomic HDV map. Lower drawing: The previously mapped HDV genomic UV-crosslinkable element is indicated on the left via its recurring sequences (bold type, raised or lowered); the template for the antigenomic UV-crosslinkable element is similarly depicted on the right (italicized, highlighted open type, raised or lowered).

Instead, as shown in Figures 3 and 4 ▶ ▶, the two sequences that form each of these two local tertiary structural elements map at different but adjacent sites in the viroidlike domain of HDV. In particular, as shown by the linear maps of each strand (Fig. 3 ▶), the two runs of sequence that comprise the UV-crosslinkable element are flanked by (in the genomic strand) or flank (in the antigenomic strand) the two sequences that encode the UV-crosslinkable element in the complementary strand. When the linear maps are shown folded back into the collapsed rod structure (Fig. 3 ▶), the two UV-crosslinkable blocs (filled rectangles) map directly across from one another (as in Fig. 2 ▶). In the genomic strand, the two sequence blocs that encode the antigenomic UV-crosslinkable element (hatched rectangles) also map across from one another, and just to the right of the UV-sensitive genomic element. The same is true in the antigenomic collapsed rod structure, except that the template sequences (hatched) map just to the left of the UV-crosslinkable element (filled). Thus we have two classes of elements in each HDV strand: one that crosslinks under UV, and one that is the template for the opposite strand‘s UV-crosslinkable element.

Figure 4 ▶ shows the sequence context for the elements studied here in each HDV strand of the collapsed rod circular structure. In both maps, the UV-crosslinkable elements‘ recurring sequences are shown in bold type; and the templates‘ common sequences are highlighted in open, italic type. In addition to the sequence repeats, the regions depicted in each of the two maps in Figure 4 ▶ have further similarities: First, the UV-crosslinkable tertiary structural elements exhibit few potential base pairs, enhancing their potential to engage in higher order folding; second, the template elements similarly lack potential secondary structure and thus also exhibit enhanced tertiary structural potential (despite our inability to detect them, at least in HDV, by seeking efficient UV crosslinking); and third, the two potential tertiary elements in each strand (Fig. 4 ▶) are embedded among stable base-paired stems on either side of their locale (7–8 bp), as well as between them (6 bp).

Although it is possible that these two classes of elements could have arisen by some kind of partial RNA gene duplication, their sequences‘ interspersion in the linear maps (Fig. 3 ▶) would require a very complex multistep copy-choice process to bring this about. It seems more likely that they arose independently from adjacent sequences in this part of the collapsed rod, which is already known to encode multiple functions on both strands. Perhaps such elements are sometimes recognized in tandem. In any event, it seems strange that either of the two classes of HDV tertiary elements could have survived by accident. It is more likely that, once in place, they have been conserved for protein recognition or some other advantageous purpose.

Correlations with biological function

Control of ribozome action

Figure 5 ▶ shows two alternate structures for the left-hand end of antigenomic HDV RNA. The UV-crosslinkable element is represented by a “pinched” domain in the vicinity of residue 700 (lower strand). The alternate folding of bases between 700–750 and 800–850, forming a cruciform (lower drawing), takes place in HDV RNA as the first step in ribozyme formation (Branch and Robertson 1991). In the genomic HDV strand, the exceptional stability of the UV-crosslinkable domain prevents the remaining steps of ribozyme formation and the self-cleavage of completed RNA strands that would otherwise result. As first shown by Sharmeen et al. (1988), HDV antigenomic RNAs containing only the upper portions of the strands shown in Figure 5 ▶ undergo efficient self-cleavage; but as soon as the bases from 650 to 790 are in place, cleavage is completely blocked. The UV-crosslinkable element mapped here provides a stable block to ribozyme formation and explains this survival of intact antigenomic strands, both in vitro and in vivo, and in both the collapsed rod and cruciform structures. The relationship (if any) between the tertiary structural elements discussed here, and the alternative ones that form when some of the same sequences in the ribozyme-containing strands of HDV fold up into their enzymatically active structures (as detected by X-ray crystallography; Ferre-D‘‘Amare et al. 1998) is an interesting topic that is beyond the scope of this communication.

FIGURE 5.

Alternate secondary structures for the HDV antigenomic strand. The UV-crosslinkable element of local tertiary structure is a common feature of both structures shown, represented by a “pinched” domain in the vicinity of residue 700 (lower strand). The alternate folding of bases between 700–750 and 800–850 is shown, forming a cruciform in the lower drawing. HDV genomic and antigenomic RNAs can both fold into two alternate configurations like the ones shown here, as first described by Branch and Robertson (1991). As proposed by Robertson et al. (1996), the two structures depicted here are likely to differ in their ability to bind host proteins such as PKR. In the antigenomic strand, the two alternate structures could regulate the relative affinities of PKR and the ADAR RNA editing enzyme.

Host protein binding

Consistent with the idea that local tertiary structures like those identified here can be protein recognition signals, loop E of eukaryotic 5S rRNA is part of the binding site for transcription factor TFIIIA (Romaniuk et al. 1987) and ribosomal protein L5 (Allison et al. 1991). The two sets of structural elements discussed here (the “HDV elements”) are novel in that they do not contain sequences in common with the E-loop motif, but both classes of potential tertiary structure in HDV (the UV-crosslinkable and the template regions) has sequence identities that may also help to predict their recurrence in other RNAs. In this way—as has been the case with the E-loop motif—other RNAs can be screened for HDV elements. Progress in this direction would advance if we could also discern the biological roles for these regions in HDV RNA.

Activation of host PKR. HDV antigen is phosphorylated in vivo during viral infection, and several studies now indicate a role for the host protein kinase PKR in this process (Yeh et al. 1996; Bichko et al. 1997; Chen et al. 2002). The PKR kinase is known be activated by the antigenomic strand of HDV RNA, including the delta 13/3 subdomain with the tertiary structural element(s) reported here (Robertson et al. 1996). Additional studies will be needed to assess the roles of genomic versus antigenomic structures in PKR‘s action in vivo.

RNA editing signals. As mentioned above, one feature that PKR and mammalian RNA editing activities (ADARs) have in common is RNA-binding sites called dsRBMs. In fact, PKR has two copies of this motif, that can interact with about 70 bp of highly structured RNA (Green and Mathews 1992; Circle et al. 1997), whereas the RNA editing activities have 2–3 dsRBM sites (Melcher et al. 1996). The HDV antigenomic RNA strand—in its role as mRNA for HDV antigen—undergoes RNA editing in vivo during HDV‘s life cycle so that it encodes shorter and longer versions of the antigen that share a common amino terminus. Recent studies have shown that in all likelihood, a host ADAR enzyme catalyzes this step (Polson et al. 1996; Sato et al. 2001). Because, like PKR, the ADAR enzymes utilize the dsRBM motif in RNA recognition, it is possible that recognition of the HDV mRNA editing site at residue 1012 could involve the antigenomic domain of local tertiary structure (see Figs.1, 3 ▶ ▶). Recent studies on RNA editing of HDV and related mRNAs in vitro support this hypothesis (O.D. Neel, M. Sheth, J. Yang, and H.D. Robertson, in prep.).

Finding out if antigenomic tertiary structure in HDV RNA helps to specify its editing will require further studies of its context and that of other RNA editing signals recognized by ADAR enzymes. In this regard, O.D. Neel, M. Sheth, J. Yang, and H.D. Robertson (in prep.) have recently found an efficiently crosslinkable UV-sensitive element of local tertiary structure, with extensive homology to that in HDV antigenomic RNA, near the editing site of a host mRNA well known to undergo RNA editing with high efficiency in vivo. Furthermore, they have detected nearby a second, less efficiently crosslinkable UV-sensitive element with sequence homology to the second or “template” HDV elements postulated here (Figs. 3, 4 ▶ ▶). Experiments like those defining the E-loop and the HDV PKR site(s) will be needed to explain fully the involvement of such structural elements in the RNA editing process.

We conclude that there are sufficient numbers of recurring features in local RNA tertiary elements—and enough significant potential correlations with biological function—to justify extensive additional investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sylvia Genus for outstanding technical assistance. We thank Dr. Timothy W. Nilsen for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grants AI-31067 and DK-56424 to HDR.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2173903.

REFERENCES

- Allison, L.A., Romaniuk, P.J., and Bakken, A.H. 1991. RNA–protein interactions of stored 5S RNA with TFIIIA and ribosomal protein L5 during Xenopus oogenesis. Dev. Biol. 144: 129–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atmadja, J., Brimacombe, R., Blocker, H., and Frank, R. 1985. Investigation of the tertiary folding of Escherichia coli 16S RNA by in situ intra-RNA cross-linking within 30S ribosomal subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 13: 6919–6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrell, B.J. 1971. Fractionation and sequence analysis of radioactive nucleotides. In Procedures in nucleic acids research (eds. G.L. Cantoni and D.R. Davies), Vol. 2, pp. 751–779. Harper & Row, New York.

- Bichko, V., Bank, S., and Taylor, J. 1997. Phosphorylation of the hepatitis delta virus antigens. J. Virol. 71: 512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch, A.D. and Robertson, H.D. 1991. Efficient trans cleavage and a common structural motif for the ribozymes of the human HDV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88: 10163–10167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch, A.D., Benenfeld, B.J., and Robertson, H.D. 1985a. Ultraviolet light-induced crosslinking reveals a unique region of local tertiary structure in potato spindle tuber viroid and HeLa 5S RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 82: 6590–6594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1985b. Unusual properties of two branched RNA‘s with circular and linear components. Nucleic Acids Res. 13: 4889–4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch, A.D., Benenfeld, B.J., Baroudy, B.M., Wells, F.V., Gerin, J.L., and Robertson, H.D. 1989a. An ultraviolet-sensitive RNA structural element in a viroid-like domain of the hepatitis delta virus. Science 243: 649–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch, A.D., Benenfeld, B.J., and Robertson, H.D. 1989b. RNA fingerprinting. Methods Enzymol. 180: 130–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch, A.D., Benenfeld, B.J., Paul, C.P., and Robertson, H.D. 1989c. Analysis of ultraviolet-induced RNA–RNA crosslinks: A means for probing RNA structure–function relationships. Methods Enzymol. 180: 418–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch, A.D., Benenfeld, B.J., Baroudy, B.M., Buckler-White, A., Gerin, J.L., and Robertson, H.D. 1990a. The novel tertiary structure in delta RNA may function as a ribozyme control element. In The hepatitis delta virus (eds. J.L. Gerin and F. Rizzetto), pp. 257–264. Alan R. Liss, New York. [PubMed]

- Branch, A.D., Levine, B.J., and Robertson, H.D. 1990b. The brotherhood of circular RNA pathogens: Viroids, circular RNA satellites and the HDV. Semin. Virol. 1: 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, S.E. and Burke, J.M. 1994. A photo-cross-linkable tertiary structure motif found in functionally distinct RNA molecules is essential for catalytic function of the hairpin ribozyme. Biochemistry 33: 992–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-W., Tsay, Y.-G., Wu, H.-L., Lee, C.-H., Chen, D.-S., and Chen, P.-J. 2002. The double-stranded RNA activated kinase (PKR) can phosphorylate hepatitis D virus small delta antigen at functional serine and threonine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 33058–33067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circle, D.A., Neel, O.D., Robertson, H.D., Clarke, P.A., and Mathews, M.B. 1997. Surprising specificity of PKR binding to HDV genomic RNA. RNA 3: 438–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll, C.C., Munishkin, A., Yuen-ling, C., Ren, Z., Wool, I.G., and Steitz, T.A. 1998. Crystal structure of the ribosomal RNA domain essential for binding elongation factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 13436–13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs, W.D. and Cech, T.R. 1990. An ultraviolet-inducible adenosine–adenosine cross-link reflects the catalytic structure of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Biochemistry 29: 5605–5613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1996. Kinetic pathway for folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme revealed by three UV-inducible crosslinks. RNA 2: 718–732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre-D‘Amare, A.R., Zhou, K., and Doudna, J.A. 1998. Crystal structure of a hepatitis delta ribozyme. Nature 395: 567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.R. and Mathews, M.B. 1992. Two RNA-binding motifs in the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase, DAI. Genes & Dev. 6: 2478–2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier-Takada, C., Lumelsky, N., and Altman, S. 1989. Specific interactions in RNA enzyme–substrate complexes. Science 246: 1578–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel, K.J. and Burke, J.M. 2001. A conformational change in the “loop E-like” motif of the hairpin ribozyme is coincidental with domain docking and is essential for catalysis. Biochemistry 40: 3723–3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinck, R., Westhof, E., Walker, S., Afshar, M., Collier, A., and Aboul-Ela, F. 2000. A potential RNA drug target in the hepatitis C virus internal ribosomal entry site. RNA 6: 1423–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leontis, N.B. and Westhof, E. 1998. A common motif organizes the structure of multi-helix loops in 16S and 23S ribosomal RNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 283: 571–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukavsky, P.J., Otto, G.A., Lancaster, A.M., Sarnow, P., and Puglisi, J.D. 2000. Structures of two RNA domains essential for hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site function. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 1105–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, A.J., Lytle, J.R., Gomez, J., and Robertson, H.D. 2001. Hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site RNA contains a tertiary structural element in a functional domain of stem-loop II. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 2535–2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher, T., Maas, S., Herb, A., Sprengel, R., Seeburg, P.H., and Higuchi, M. 1996. A mammalian RNA editing enzyme. Nature 379: 460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niniol, J., Favre, A., and Yaniv, M. 1969. Molecular model for transfer RNA. Nature 223: 1333–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson, A.G., Bass, B.L., and Casey, J.L. 1996. RNA editing of hepatitis delta virus antigenome by dsRNA adenosine deaminase. Nature 380: 454–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince, J.B., Taylor, B.H., Thurlow, D.L., Ofengand, J., and Zimmermann, R.A. 1982. Covalent crosslinking of tRNA1Val to 16S RNA at the ribosomal P site: Identification of crosslinked residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79: 5450–5454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, H.D. 1992. Replication and evolution of viroid-like pathogens. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 176: 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, H.D., Manche, L., and Mathews, M.B. 1996. Paradoxical interactions between human delta hepatitis agent RNA and the cellular protein kinase PKR. J. Virol. 70: 5611–5617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romaniuk, P.J., de Stevenson, I.L., and Wong, H.H. 1987. Defining the binding site of Xenopus transcription factor IIIA on 5S RNA using truncated and chimeric 5S RNA molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 15: 2737–2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S., Wong, S.K., and Lazinski, D.W. 2001. Hepatitis delta virus minimal substrates competent for editing by ADAR1 and ADAR2. J. Virol. 75: 8547–8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.S., Choo, Q.L., Weiner, A.J., Ou, J.H., Najarian, R.C., Thayer, R.M., Mullenbach, G.T., Denniston, K.J., Gerin, J.L., and Houghton, M. 1986. Structure, sequence and expression of the hepatitis delta viral genome [published erratum in Nature, 1987, 328: 456]. Nature 323: 508–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberly, B., Varani, G., and Tinoco, I.J. 1993. The conformation of loop E of eukaryotic 5S ribosomal RNA. Biochemistry 32: 1078–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv, M., Favre, A., and Barrell, B.G. 1969. Structure of transfer RNA. Evidence for interaction between two non-adjacent nucleotide residues in tRNA from Escherichia coli. Nature 223: 1331–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, T.-S., Lo, S.J., Chen, P.-J., and Lee, Y.-H.W. 1996. Casein kinase II and protein kinase C modulate hepatitis delta virus RNA replication but not empty viral particle assembly. J. Virol. 70: 6190–6198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwieb, C. and Schuler, D. 1989. Low resolution three-dimensional models of the 7SL RNA of the signal recognition particle, based on an intramolecular cross-link introduced by mild irradiation with ultraviolet light. Biochem. Cell Biol. 67: 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwieb, C., Ross, A., Rinke, J., Meinke, M., and Brimacombe, R. 1978. Evidence for RNA–RNA cross-link formation in Escherichia coli ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 5: 2705–2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]