Abstract

Phosphorothioate-substitution experiments are often used to elucidate functionally important metal ion-binding sites on RNA. All previous experiments with SP-phosphorothioate-substituted RNAs have been done in the absence of structural information for this particular diastereomer. Yeast U6 RNA contains a metal ion-binding site that is essential for spliceosome function and includes the pro-SP oxygen 5′ of U80. SP-phosphorothioate substitution at this location creates spliceosomes dependent on thiophilic ions for the first step of splicing. We have determined the solution structure of the U80 SP-phosphorothioate-substituted U6 intramolecular stem–loop (ISL), and also report the refined NMR structure of the unmodified U6 ISL. Both structures were determined with inclusion of 1H–13C residual dipolar couplings. The precision of the structures with and without phosphorothioate (RMSD = 1.05 and 0.79 Å, respectively) allows comparison of the local and long-range structural effect of the modification. We find that the U6-ISL structure is unperturbed by the phosphorothioate. Additionally, the thermodynamic stability of the U6 ISL is dependent on the protonation state of the A79–C67 wobble pair and is not affected by the adjacent phosphorothioate. These results indicate that a single SP-phosphorothioate substitution can be structurally benign, and further validate the metal ion rescue experiments used to identify the essential metal-binding site(s) in the spliceosome.

Keywords: U6 snRNA, phosphorothioate, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), metal ion, residual dipolar coupling (RDC)

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic genes contain introns that must be accurately spliced out of pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA). This splicing reaction is catalyzed by the spliceosome, a dynamic molecular assembly that requires five snRNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) and >70 proteins to perform two successive phosphotransesterification reactions (Nilsen 1998; Burge et al. 1999; Brow 2002). U6 and U2 snRNAs are required in both steps of the reaction, directly assisting in the concerted excision of the lariat intron and the ligation of the flanking exons through a 5′–3′ phosphodiester linkage (Collins and Guthrie 2000). Recently, a U2/U6 complex was shown to catalyze a reaction similar to the first step of splicing in the absence of protein, supporting the hypothesis of an RNA active site in the spliceosome (Valadkhan and Manley 2001). In addition, inner-sphere coordination of each leaving group by a catalytic divalent metal ion is an important feature of the two chemical steps of pre-mRNA splicing (Sontheimer et al. 1997; Gordon et al. 2000).

Central to our understanding of the spliceosome is the identification of metal-binding sites and functionally important phosphate oxygens within snRNAs. Single-atom substitution studies of U6 snRNA have revealed several phosphate oxygens that are essential to splicing, revealing potential magnesium-binding sites within the spliceosome (Fabrizio and Abelson 1992; Yu et al. 1995; Yean et al. 2000). If there is a catalytically essential contact between a metal ion and a nonbridging oxygen atom, replacement of the oxygen with a sulfur atom can introduce a functional defect and loss of activity. Such a phosphorothioate substitution substantially changes the charge distribution, polarizability, bond length, and van der Waals radius of a phosphate group (Eckstein 1979; Saenger 1984). Because Mg2+ is a hard metal that prefers an interaction with a hard ligand (e.g., oxygen), a sulfur substitution at a critical Mg2+–RNA contact may significantly contribute to loss of activity. Conversely, more thiophilic metal ions, such as Cd2+ and Mn2+, can restore the metal contact to a sulfur-substituted RNA, because of their strong preference or tolerance for sulfur as a ligand (Pecoraro et al. 1984).

Lin and colleagues have identified an essential and stereospecific metal ion coordination site 5′ to nucleotide U80 in yeast U6 snRNA (Yean et al. 2000). SP-phosphorothioate modification of nucleotide U80 (U6/SP-U80) in U6 abolishes the splicing reaction but does not interfere with spliceosome assembly. Cd2+ and Mn2+ stereospecifically rescue the U6/SP-U80 spliceosome, but not the corresponding RP-phosphorothioate modification (U6/RP-U80) spliceosome. Furthermore, increasing concentrations of Mg2+ effectively compete to inhibit the Mn2+ reaction, halting the activity of the U6/SP-U80 spliceosome. These results demonstrate that the conformation of the SP-phosphorothioate-modified spliceosome is not grossly altered and offer strong evidence for an essential RNA–metal interaction, further strengthening the hypothesis that the spliceosome may be a ribozyme.

However, interpretation of most chemical modification-interference experiments relies on the assumption that the modification does not structurally perturb functionally important regions of the molecule. In the catalytically active spliceosome, nucleotide U80 is located at the internal loop of the highly conserved intramolecular stem loop (ISL) of U6 RNA (Fig. 1 ▶). Recent structural studies indicate that the isolated U6-ISL RNA binds metal ions at the U80 SP position in a stereospecific manner similar to the intact spliceosome (Huppler et al. 2002). However, it could be argued that a sulfur substitution in the internal loop region of the U6 ISL might alter the RNA structure and/or perturb its thermodynamic stability, in which case metal binding to the phosphorothioate may not report an essential metal ion interaction within the native spliceosome.

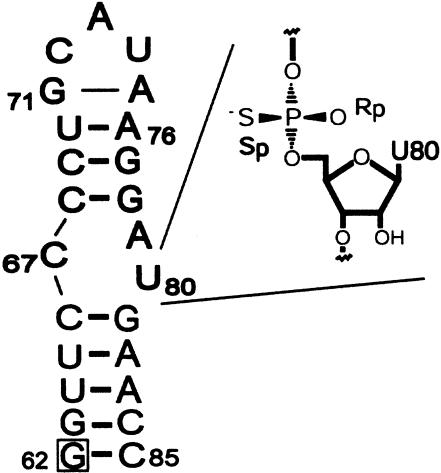

FIGURE 1.

Secondary structure of the U6 ISL RNA representing nucleotides 62–85 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The position of the phosphorothioate modification for the SP-ISL construct is expanded, and the A62G substitution is boxed.

Previously it was demonstrated that multiple RP-phosphorothioate modifications substantially altered the conformation of an RNA hairpin containing the binding site for phage MS2 capsid protein (Smith and Nikonowicz 2000). Other crystallography and NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) studies involving DNA and DNA:RNA hybrid duplexes have shown that RP-phosphorothioate modifications have relatively little effect on structure, except to increase the population of a C3′-endo conformation in adjacent deoxyribose sugars (Cruse et al. 1986; Gonzalez et al. 1994; Bachelin et al. 1998). On the other hand, structural studies of SP phosphorothioates have been hampered by the fact that they cannot be transcriptionally incorporated, as with the RP modification. Hence SP-phosphorothioate-substituted RNA must be synthesized chemically as a mixture of diastereomers and purified, making preparative-scale 13C, 15N labeling for NMR either problematic or cost prohibitive. Because of the above reasons, no complete structural data exist for SP-phosphorothioate-containing RNAs.

To address whether the SP-phosphorothioate substitution at U80 alters the conformation of the U6-ISL RNA, we have used UV and NMR spectroscopy to determine the thermodynamic properties and solution structure of the U80 SP-phosphorothioate-substituted U6 ISL (hereafter referred to as SP-ISL; Fig. 1 ▶), aided by the measurement of 1H–13C residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) at natural 13C abundance. To sufficiently determine the impact of the SP-phosphorothioate substitution on both the local and long-range structure of the U6 ISL, we have also refined the unmodified U6-ISL structure (hereafter referred to as the WT-ISL; Huppler et al. 2002) using residual dipolar couplings. The thermodynamic stabilities of the unmodified and SP-phosphorothioate-substituted U6-ISL RNAs were determined using temperature-controlled UV spectroscopy. These results indicate that the SP phosphorothioate is structurally and thermodynamically benign, and further validate the use of phosphorothioate experiments to study essential metal ion interactions within the U6-ISL RNA and, potentially, other systems.

RESULTS

Thermodynamic comparison of SP-ISL and WT-ISL RNA

The secondary structure of the U6 ISL, representing nucleotides 62–85 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae U6 RNA, is shown in Figure 1 ▶. Both wild-type (WT) and SP-ISL RNAs incorporate an A62G substitution, which has no effect on the growth rate of yeast at 30°C (Fortner et al. 1994) and no effect on the overall structure of the ISL (Huppler et al. 2002) but allows for optimal in vitro transcription conditions using T7 RNA polymerase.

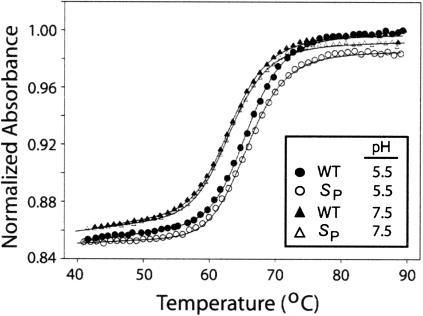

The thermodynamic stabilities of the WT- and SP-ISL RNAs were analyzed at pH 5.5 and pH 7.5 by temperature-dependent UV spectroscopy (Fig. 2 ▶). The Tm values of 65.8°C and 65.9°C at pH 5.5, and 63.3°C and 63.4°C at pH 7.5 were determined for the WT and SP-ISL RNAs, respectively (Table 1 ▶). The 2.5°C higher Tm values at pH 5.5 can be assigned to protonation of the N1 atom of A79 to form the C67–A79 wobble pair, which has an apparent pKa of 6.5 and contributes one hydrogen bond to the internal loop structure when protonated (Huppler et al. 2002). By fitting the UV melting data, the free energy gained by protonation (ΔΔG) is estimated to be −0.7 ± 0.3 kcal/mole (Table 1 ▶). The UV-melting curves indicate that thermodynamic stability and adenine protonation remain unchanged for the WT- and SP-ISL RNAs, and that the SP-ISL is thermodynamically indistinguishable from wild type.

FIGURE 2.

Thermal stability data for the SP- and WT-ISLs. Open circles and triangles represent SP RNA, and closed circles and triangles represent WT RNA at pH 5.5 and pH 7.5, respectively. Data were collected in duplicate at a wavelength of 260 nm. Both pH 5.5 and pH 7.5 samples contain 1 μM RNA, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, and 200 mM KCl. The curve fits to the data are indicated by solid lines. The thermodynamic parameters and melting temperature (Tm) obtained from the curve fitting from each experiment are summarized in Table 1 ▶.

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters of wild-type (WT) and Sp-ISL RNAs derived from temperature-dependent UV spectroscopy

| RNA | pH = 5.5 Tm (°C) (± 0.05) |

pH = 7.5 Tm (°C) (± 0.05) |

ΔΔ GpH 5.5–7.5 (± 0.30 kcal/mole) |

| WT | 65.9 | 63.3 | −0.7 |

| Sp | 65.8 | 63.4 | −0.7 |

NMR analysis of WT- and SP-ISL RNAs

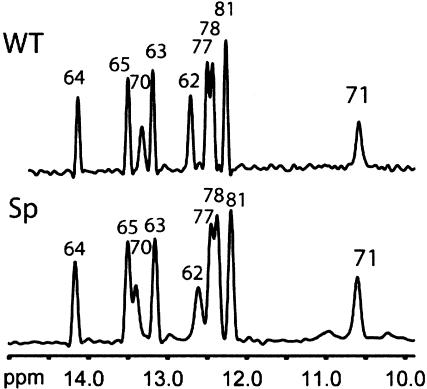

A comparison of the WT- and SP-ISL 1D 1H NMR imino spectra show no apparent alteration for the exchangeable protons (Fig. 3 ▶). The high degree of similarity in these spectra indicates that both stem–loop structures contain identical base pairings, with two helices separated by an internal loop and a pentaloop G71–A75 base pair, as previously observed (Huppler et al. 2002). This implies that the overall fold is similar for both RNAs.

FIGURE 3.

The 600-MHz 1D 1H NMR spectra of the imino region. Peak assignments are indicated. The WT-ISL spectrum was acquired at pH 7.0, 10°C, 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM RNA. The SP-ISL spectrum was acquired at pH 6.8, 10°C, 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM RNA.

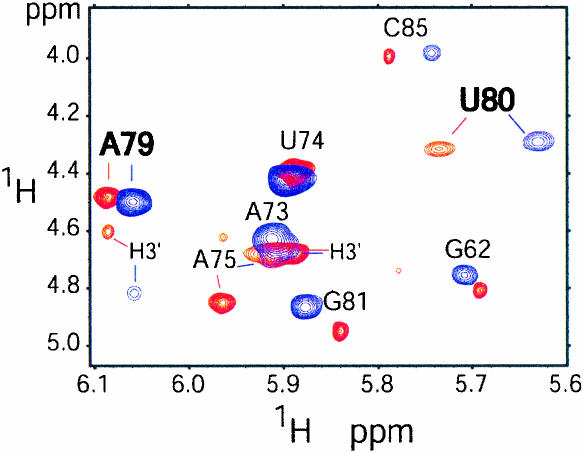

Interproton distance and dihedral angle information for nonexchangeable resonances was obtained with 2D 1H–1H NOESY (nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy) and 2D 1H–1H TOCSY (total correlation spectroscopy) NMR experiments. The chemical shifts of proton and carbon resonances differ only slightly between both RNA molecules and primarily occur in the internal loop region (nucleotides 68, 69, 79–81; Figs. 4, 5 ▶ ▶). Small changes in proton chemical shifts for the phosphorothioate-adjacent nucleotides A79 and U80 are observed, which may reflect the different chemical and electrostatic properties introduced by the sulfur atom and possibly conformational differences. To address whether the phosphorothioate modification affects the local conformation of the backbone, the ribose sugar puckers were analyzed with a 2D 1H–1H TOCSY experiment (Fig. 4 ▶). Sugar puckers that are in the S-type range (including C2′-endo) or undergo conformational averaging give rise to intraribose H1′–H2′ correlations in TOCSY spectra, whereas C3′-endo sugar pucker conformations do not. The same set of ribose correlations is observed for the WT- and SP-ISL RNAs in the TOCSY experiment (Fig. 4 ▶). These include the terminal nucleotides G62 and C85, A79–G81, and the pentaloop nucleotides 73–75. Furthermore, the peak volumes for the correlations of the WT- and SP-ISL RNAs are nearly identical in this experiment, indicating that the SP phosphorothioate does not alter the sugar puckers of the adjacent ribose groups. The ribose sugar of A79 is closest to the phosphorothioate modification, and the A79 H3′ proton displays the largest change in proton chemical shift as a result of the phosphorothioate modification (Fig. 4 ▶). In both SP- and WT-ISL RNAs, the presence of a strong H1′–H2′ and weak H1′–H3′ coupling for the A79 ribose indicates a sugar pucker in the S-type range (Fig. 4 ▶), which was restrained to 145° ± 30° in the structure calculations. On the other hand, U80 displays intermediate H1′–H2′ couplings, indicating that the U80 sugar puckers undergo conformational averaging in both molecules (Fig. 4 ▶). Therefore, the U80 sugar puckers were unrestrained for all structure calculations.

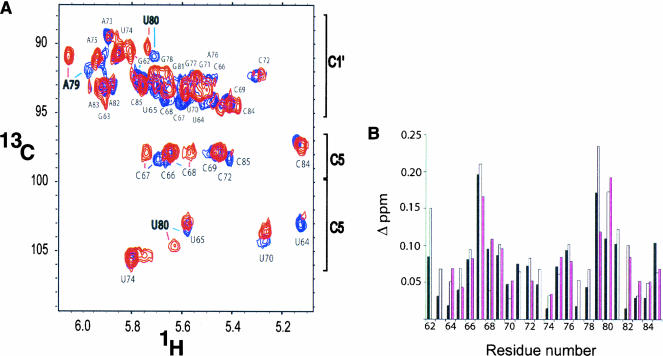

FIGURE 4.

The 750-MHz 2D 1H–1H TOCSY spectra (40 msec mixing time) comparing H1′–H2′ and H1′– H3′ ribose proton correlations between the WT-ISL (red; 1.5 mM RNA at pH 6.2, 50 mM NaCl) and the SP-ISL (blue; 1 mM RNA at pH 6.2, 50 mM NaCl) at 30°C. Unless otherwise noted, all resonances indicate an H1′–H2′ correlation.

FIGURE 5.

(A) Representative HSQC spectrum and chemical shift comparison between the WT-ISL and the SP-ISL. Natural abundance 1H–13C HSQC experiment of the C1′ (89–94 ppm), cytosine C5 (96–98 ppm), and uridine C5 (103–106 ppm) regions. The WT-ISL correlations are red, and the SP -ISL correlations are blue. The pH is 6.2 ± 0.1 for both RNA samples. (B) Observed changes in chemical shift (Δ ppm) upon SP-phosphorothioate substitution 5′ to nucleotide U80. Changes are plotted by residue number and include: C1′ and H1′ (black), C6/8 and H6/8 (white), and C5/2 and H5/2 (pink) resonances. Changes in chemical shift were calculated from the equation Δ ppm = [(Δ 1H ppm)2 + (Δ 13C ppm − αC)2]0.5, where Δ ppm is the difference in parts per million between the chemical shifts of the WT-ISL and the SP-ISL, and αC is the scaling factor to normalize the magnitude of the carbon chemical shift changes relative to the proton scale (Butcher et al. 2000). The αC correction factors were 0.14, 0.16, and 0.32 for C1′, C6/8, and C5/2, respectively.

The 2D 1H–13C HSQC (heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy) spectra of both RNAs at natural 13C abundance indicate that, despite small changes in the A79 and U80 chemical shifts, the overall chemical shift differences between the SP- (blue) and the WT-ISL (red) are very minor (Fig. 5A ▶). The small change in chemical shift for the terminal G62 and C85 resonances is likely to be caused by the lack of a phosphate at the 5′ end of the SP-ISL, which is present on the transcriptionally produced WT-ISL (Fig. 5B ▶). The 2D 1H–1H NOESY data at different mixing times (75, 150, 250, and 300 msec) reveal no detectable differences in NOE (nuclear Overhauser effect) patterns for the two molecules (data not shown). The 2D 1H–31P HETCOR (heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy) and 1D 31P NMR experiments also reveal no detectable difference in 31P chemical shifts, aside from the ∼60-ppm change in chemical shift for the U80 phosphorothioate (data not shown).

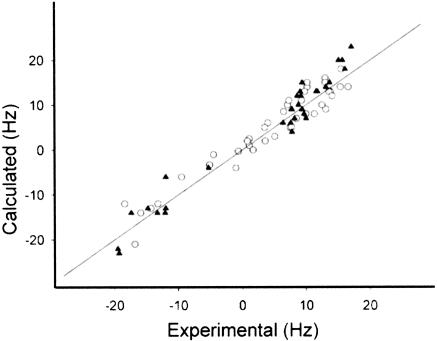

For the WT- and SP-ISL RNAs, 31 and 40 1H–13C residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) were measured, respectively (Table 2 ▶), and incorporated into the structure calculations. Residual dipolar couplings were measured at 13C natural abundance for the SP-ISL RNA, and these were critical for the structure determination, because only a limited NOE data set could be collected without an isotopically enriched sample (Table 2 ▶). Inclusion of the natural abundance RDC data increased the precision of the SP-ISL structure from an RMSD (over all heavy atoms) of 2.14 ± 0.8 Å to 1.05 ± 0.3 Å (Table 2 ▶). Figure 6 ▶ demonstrates the excellent agreement between the experimentally derived and back-calculated RDCs for the two sets of structure calculations. Significantly more NOEs were assigned for the WT- than the SP-ISL (506 vs. 322), which is reflected in the slightly lower RMSD of 0.79 ± 0.3 Å obtained for the WT-ISL (Table 2 ▶).

TABLE 2.

Structural statistics for the U6 ISL and SP-ISL

| U6 ISL | SP-ISL | |||

| With dipolar coupling data | Without dipolar coupling dataa | With dipolar coupling data | Without dipolar coupling dataa | |

| Structures | ||||

| Accepted | 20 | 40 | 17 | 17 |

| Calculated | 100 | 200 | 100 | 100 |

| NOE-derived distance restraints (per nucleotide) | 506 (21.1) | 521 (21.7) | 322 (13.4) | 322 (13.4) |

| Dihedral restraints | 145 | 145 | 144 | 144 |

| Hydrogen-bond restraints | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Dipolar coupling restraints | 31 | — | 40 | — |

| RMSD, all heavy atoms to the mean structure (Å) | ||||

| Overall (62–71, 73, 75–85) | 0.79 ± 0.30b | 1.46 ± 0.4 | 1.05 ± 0.3b | 2.14 ± 0.8 |

| Internal loop (66–68, 78–81) | 0.46 ± 0.2c | 0.44 ± 0.3 | 0.49 ± 0.2c | 0.58 ± 0.4 |

| NOE violations (>0.5 Å) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ave. dihedral violations (>5.0°) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ave. NOE RMSD (Å) | 0.027 | 0.018 | 0.029 | 0.041 |

| Ave. dihedral RMSD (°) | 0.640 | 1.270 | 0.710 | 0.761 |

| Ave. RDC RMSD (Hz) | 2.38 ± 0.11 | — | 2.35 ± 0.16 | — |

aPreviously determined (Huppler et al. 2002).

bThe RMSD for all heavy atoms excluding bulged nucleotides (62–71, 73, 75–85) is 1.16 ± 0.4 Å between U6 ISL and SP-ISL RNAs.

cThe internal loop (66–68, 78–81) RMSD for all heavy atoms is 0.55 ± 0.3 Å between U6 ISL and SP-ISL RNAs.

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of all back-calculated (vertical) and experimental (horizontal) RDC values for the SP-ISL (circles) and U6 ISL (triangles) for the lowest energy structures. The straight line indicates experimental = calculated. Correlation coefficients (R2) of 0.96 and 0.93 were obtained for the SP-ISL and WT-ISL, respectively.

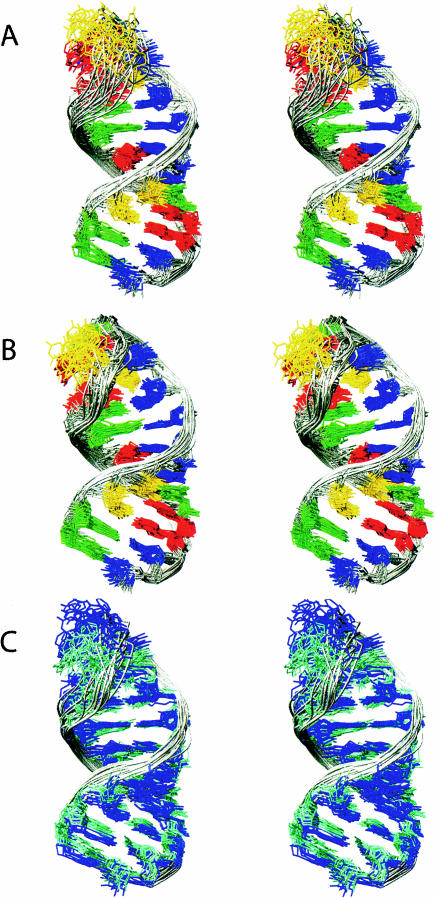

Superimposition of the SP and WT-ISL structures reflects similarities in the NMR spectra (Figs. 4, 5 ▶ ▶) and reveals that the difference between the structure ensembles is close to the RMSD values for the separate ensembles. The 10 lowest energy structures from both the SP and WT ensembles have a pairwise RMSD value to each other of 1.16 ± 0.4 Å (Table 2 ▶; Fig. 7 ▶). Both NMR ensembles adopt a near-A-helical form and consist of two helices, separated by an internal loop composed of one unpaired residue (U80), capped by a GNRA-tetraloop-like conformation (Jucker et al. 1996). The SP-ISL retains the previously observed GNR(N)A pentaloop conformation, with the U74 residue bulged out of the loop (Huppler et al. 2002). Additionally, both structures contain a readily protonated C67–+A79 wobble pair adjacent to an unpaired but stacked U80 nucleotide, also as previously observed (Huppler et al. 2002).

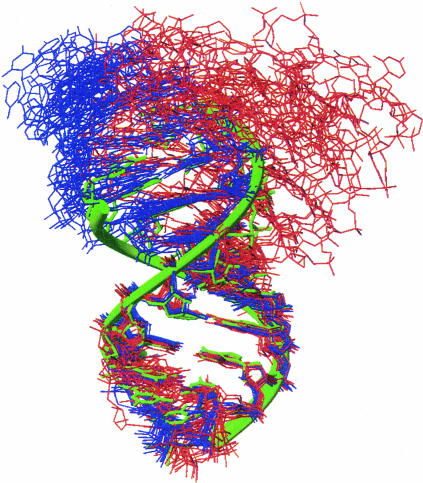

FIGURE 7.

Stereo view of the NMR solution structure ensemble for the SP-ISL (A) and the WT-ISL (B). The 17 SP-ISL and 20 U6 ISL structures represent the lowest energy structures from the structure calculations that incorporated residual dipolar couplings. The phosphate backbone is designated by the gray ribbon, guanosines are green, uridines are yellow, cytidines are blue, and adenosines are red. The RMSD over all heavy atoms is 1.05 ± 0.3 Å for the SP -ISL (A) and 0.79 ± 0.3 Å for the WT-ISL (B). Superimposition of the 10 lowest energy structures from each ensemble (C), with SP-ISL in blue and the U6 ISL in aquamarine, gives a direct comparison across both structures. The RMSD over all heavy atoms for these 20 structures is 1.16 ± 0.4 Å.

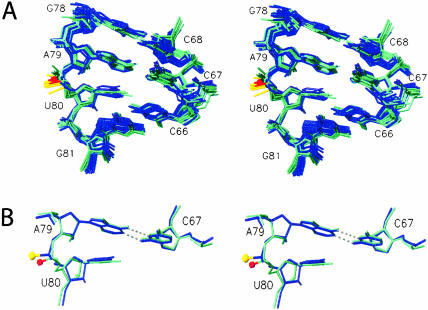

In the internal loop region, previous studies determined that stereoselective metal ion binding is modulated by the protonation state of the N1 adenine in the C–A wobble pair adjacent to nucleotide U80 (Huppler et al. 2002). The SP-ISL RNA displays pH-dependent proton chemical shift changes within the internal loop that are similar to the WT-ISL at pH 6.2 and pH 7.5 (data not shown). The primary chemical shift differences caused by the phosphorothioate substitution in the HSQC and NOE data occur at pH 7.0 and reside around nucleotides U80, A79, and C67 (Fig. 5B ▶). An average chemical shift change of roughly 0.20 ppm for resonances of these nucleotides indicates that a sulfur substitution does affect the chemical environment of the internal loop. However, similarities observed in backbone and ribose chemical shift and coupling information obtained from 2D 1H–1H TOCSY, 1H–13C HSQC, and 1H–31P HETCOR NMR experiments (Figs. 4, 5 ▶ ▶; data not shown) indicate that the ISL RNA is able to accommodate an SP-phosphorothioate substitution with no substantial change in conformation. Figure 8 ▶ reveals this through the superposition of the internal loop region (66–68, 78–81) for the SP- and WT-ISL structures, with a local RMSD of 0.55 ± 0.3 Å. The pro-SP oxygen atom (red) and SP sulfur atom (gold) of U80 for both ensembles is directed outward toward the minor groove.

FIGURE 8.

Stereo superimposition of the internal loop region of the SP-ISL structures (blue) and 10 WT-ISL structures (aquamarine). The S1P and O1P atoms 5′ to nucleotide U80 are gold and red, respectively. (A) Stereo superimposition of the internal loop region of the 10 lowest energy SP-ISL and WT-ISL structures. The RMSD for all heavy atoms is 0.55 ± 0.3 Å between the internal loop (66–68, 78–81) of the U6 ISL and the SP-ISL. (B) Stereo superimposition of the internal loop region from the single lowest energy SP-ISL and WT-ISL structures.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that the WT- and SP-ISL structures are substantially improved by the inclusion of the RDC data, as evident by the significantly lower RMSD values (Table 2 ▶). Large long-range structural differences are observed between the previous U6 ISL structures determined without RDC data (Huppler et al. 2002) and the structures reported here (Table 2 ▶). The long-range structural differences are particularly evident when the structures are superimposed over only the first five base pairs (Fig. 9 ▶). Whereas both structures contain the same base pairs and hydrogen bonds, the earlier structures lack the long-range order of the structures calculated with RDCs, similar to what has been observed for other RNAs (Sibille et al. 2001). Additionally, we notice that the entire ensemble of structures calculated with RDCs is much more A-form over the entire helix length, whereas the earlier ensemble does not occupy the same conformational space (Fig. 9 ▶). This result indicates that the ensemble of RNA structures calculated without RDC data is trapped in local conformational energy minima during the restrained molecular dynamic simulations, leading to significant deviations away from A-form geometry. Therefore, RDC restraints are likely to be critical for determining accurate nucleic acid solution structures.

FIGURE 9.

Superimposition of an ideal A-form helix (green) with the 10 lowest-energy +RDCs (blue) and −RDCs (red) SP-thiosubstituted ISL RNA structures fit over the lower helix. The A-form RNA model duplex has the sequence r(GGUUCAACCU/AGGUUGAACC), which is identical in its first five base pairs to the U6 ISL sequence.

Although fundamental chemical differences between phosphates and phosphorothioates can potentially lead to significant structural and electrostatic differences, careful interpretation of phosphorothioate-modification interference experiments has been instrumental in dissecting mechanism at the molecular level. We have demonstrated that, in certain structural contexts, a phosphorothioate substitution does not alter the overall conformation of the RNA (Figs. 7, 8 ▶ ▶). In addition to cross-validating the mainly NOE-based structure, residual dipolar couplings provide local and long-range order for the SP- and WT-ISL solution structures, enabling a direct comparison to be made at the internal loop region and across the overall molecule. The substitution of a pro-SP phosphoryl oxygen to a sulfur atom 5′ to nucleotide U80 does not significantly alter the thermodynamic stability of the RNA.

The previous structure determination of the U6 ISL in the absence of RDC data (Huppler et al. 2002) accurately defined base-pair geometries but could not precisely define the position of the U80 pro-SP oxygen. The precision of the WT- and SP-ISL structures reported here enable us to infer how the ISL might participate in a tertiary interaction. We observe that the pro-SP nonbridging phosphate oxygen is freely accessible in solution and angled toward the minor groove, whereas the pro-RP position is located within the major groove, which is less accessible. Thus, it is possible that docking of the U6 ISL through its minor groove would readily position the U80 pro-SP phosphate oxygen for a tertiary interaction that is modulated or stabilized by the essential divalent metal ion (Yean et al. 2000).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA synthesis and purification

The U6 ISL with the A62G substitution was transcribed in vitro using purified His6-tagged T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA technologies, Inc.) as previously described (Milligan and Uhlenbeck 1989; Huppler et al. 2002). All chemical reagents and unlabeled nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) except the His6-tagged T7 RNA polymerase were purchased from Sigma Chemical. Phosphorothioate-containing RNAs (Dharmacon, Inc.) were deprotected according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The U6 ISL phosphorothioate diastereomers were separated by HPLC purification using a 4.6 × 250-mm C18 reverse phase Adsorbosphere HS packed column (Alltech, Inc.). The column was equilibrated with 0.1 M ammonium acetate (pH 6.8); 0.3 μmole was the maximum amount of RNA that could be injected onto the column at one time, and a shallow 0%–10% acetonitrile elution gradient allowed for baseline separation between the diastereomers. The corresponding fractions were pooled, ethanol-precipitated, and desalted on a 15-mL G-25 gel filtration column. The purity of the isolated diastereomers was assessed by HPLC and 31P NMR spectroscopy to be ≥95% in all cases. Diastereomer assignments were made by analysis with snake venom phosphodiesterase (Slim and Gait 1991).

UV spectroscopy

Thermal stability studies were conducted on purified U6 ISL and SP-ISL RNAs using a Cary Model 1 Bio UV-visible spectrophotometer equipped with a Peltier heating accessory and temperature probe. All samples at pH 5.5 and pH 7.5 contained 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 200 mM KCl, and ∼1 μM RNA. Samples were heated to 90°C and cooled to 20°C at a rate of 2°C/min while absorbance data were collected at 260 nm in 1°C increments. Two scans were taken for each RNA. Thermodynamic values and transition temperatures (Tm) were calculated from normalized data using SigmaPlot v8.0 (SPSS Science). For the process of unfolding a stem–loop composed of a single RNA molecule (F → U), where ΔCp = 0:

|

and

|

where θ is the fraction of RNA in the unfolded state, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in kelvin. To fit a curve to the absorbance data for the U6 ISL and SP-ISL RNAs, the pretransitional and posttransitional baselines of each thermal stability curve were first determined by a linear curve fit. These baselines were used to find the fraction of unfolded RNA as a function of temperature and subsequently the values of ΔH, ΔS, and Tm. The free energy difference (ΔΔG) of each RNA at both pH values was calculated from their ΔH and ΔS values (Table 1 ▶).

NMR spectroscopy

All spectra were acquired at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison (NMRFAM) on Bruker DMX 400, 500, 600, and 750 MHz spectrometers. Natural abundance data collection was performed using a cold (cryoprobe, Bruker) single Z-axis gradient HCN probe and a Bruker QNP (quadrupole nucleus probe) tuned to phosphorous with a Z-axis gradient. All NMR data were processed with XWINNMR (Bruker) and analyzed with Felix-98 (MSI) and the NMR assignment program Sparky (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky/).

Imino proton resonances were assigned by reference to a 2D NOESY (150 msec mixing time) in 90% H2O/10% D2O at 283 K. A 1–1 spin-echo pulse sequence water suppression scheme was performed for all samples in 90% H2O/10% D2O. Nonexchangeable resonances were assigned by reference to 2D 1H–1H NOESY spectra (75, 150, 250, and 300 msec mixing times), and 2D 1H–1H TOCSY, 1H–13C HSQC, and 1H–31P HETCOR spectra were collected in 99.99% D2O at 303 K. The 1D 31P spectra were acquired at 202 MHz (500 MHz 1H) with a 5-mm quadrupole nucleus probe (QNP, Bruker). For all experiments in 99.99% D2O, the HDO resonance was suppressed using a low-power presaturation pulse. All NMR experiments for the U6 ISL and the SP-ISL RNA contained 0.8–1.5 mM RNA and 50 mM NaCl at pH 6.2, pH 7.0, or pH 7.5. All 1H, 13C heteronuclear spectra for the SP-ISL were taken at natural abundance, and the U6 ISL was assigned using standard homo- and heteronuclear methods (Dieckmann and Feigon 1997).

Partially aligned samples contained 17 mg/mL Pf1 filamentous bacteriophage (ASLA Ltd.) and allowed for measurable internuclear residual dipolar couplings for 1H–13C aromatic and sugar resonances (Hansen et al. 2000). Natural abundance 1H–13C HSQC spectra enabled the measurement (±2.0 Hz) of RDCs in the proton (F2) and carbon (F1) dimensions for the U6 ISL and SP-ISL samples. Final sample conditions before and after the addition of the phage were 0.8–1.0 mM RNA in 300 μL (pH 7.4), using a thin-wall Shigemi microcell (Shigemi Inc.).

Distance, torsion angle, and RDC constraints

Assigned NOE peak volumes were fit and integrated using the Gaussian peak-fitting function in Sparky. To assess the relative intensity of the NOE, distances were calibrated by setting the average integrated volume of the pyrimidine H5–H6 NOEs to 2.4 Å, using the r−6 distance relationship and the CALIBA macro in DYANA (Guntert et al. 1997). This calibration was then used to group NOEs into three classes: strong (1.8–3.0 Å), medium (1.8–4.5 Å), and weak (3.0–6.0 Å). NOE distances for exchangeable protons were qualitatively assigned to one of these three classes.

1H–31P HETCOR and 1D 31P reveal that all 31P chemical shifts reside between −3 and −5 ppm, except for the SP and RP diastereomers (59.5 and 57.5 ppm, respectively). Therefore, α and ζ torsion angles were set to exclude the trans range (0° ± 120°; Allain and Varani 1995). Except for the SP diastereomer, it was observed that no phosphate resonances differ by more than 0.2 ppm between the U6 ISL and the SP sulfur-substituted RNA. Nucleotides with strong H1′–H2′ couplings (C72, U74, A79), as observed in a 40-msec mixing time 2D 1H–1H TOCSY (Fig. 4 ▶), were constrained as C2′-endo (S-type; 145° ± 30°), whereas all other nucleotides were either constrained as C3′-endo or unrestrained. Intranucleotide H1′ to aromatic NOEs from a 75-msec 2D NOESY indicated that all nucleotides fell into the anti range, and were thus constrained with a χ value of −160° ± 20°. χ values of nucleotides A79 and U80 were left unrestrained. Other backbone torsion angles (β, γ, ɛ) were set to standard A-form values (±40°) only in the helical regions of the structure known to be A-form Watson-Crick helices from NOE and dihedral information.

Analysis of residual dipolar couplings was performed using XWINNMR (Bruker) software by measuring the difference between the 1H and 13C coupling for isotropic and partially aligned samples. The values of the axial (Da) and rhombic (R) components of the alignment tensor were determined by analyzing the powder pattern distribution for each experimental RDC data set and further refined by following a grid search procedure that calculates a series of structures with different rhombicities (Clore et al. 1998a,b). In addition, prediction of the alignment tensor from the converged, lowest energy structures in the presence and absence of RDCs was estimated by PALES (Zweckstetter and Bax 2000; http://spin.niddk.nih.gov/bax/software/PALES). An axial component (Da) of −14.0 Hz and a rhombic component of 0.22 were found to be the experimentally determined values for the SP-ISL structures in the CNS structure calculations. Similarly, a Da value of −14.0 Hz and an R value of 0.21 were determined for the refined U6 ISL RDC structure. These final values reflect the best agreement between the structure and the RDCs data set, as observed through the low-energy, no violation, and overall convergence rate of the structure calculation. The experimental RDCs from the final converged structures were plotted against the back-calculated predicted RDC values from CNS and were found to be in good agreement (Fig. 6 ▶).

Structure calculation and refinement

For the sulfur-substituted U80 nucleotide, a separate residue (SSU) was created in the topology files and was identical to the uridine (URI) residue with the exception of the pro-SP atom at the O1P phosphoryl oxygen position, which was named S1P to represent the SP sulfur substitution. The U80 S1P atom was created to be structurally distinct from that of the RP phosphoryl oxygen atom (O2P), in the following manner: the P–S bond was set to 1.80 Å, and the van der Waals radius of the sulfur atom to 1.90 Å. This allows the sulfur to project outward almost 0.8 Å more than the oxygen (Saenger 1984). The charge distribution parameters for the O2P atom (−0.865 esu) and the S1P atom (−0.772 esu) for SSU were set to previously determined potentials (Jaroszewski et al. 1992). This enabled the incorporation of a sulfur atom into the topology and parameter files and generated a distinct structure file for the SP-ISL RNA.

CNS 1.1 (Brunger et al. 1998; http://cns.csb.yale.edu/v1.1) was used to calculate structures using NOE distances, dihedral restraints, and residual dipolar couplings. An improved version of CNS was implemented that includes an improved harmonic potential that corrects the susceptibility anisotropy (RDC) protocol (Warren and Moore 2001). For the CNS structure calculations, an extended, unfolded structure was initially generated, from which 100 starting structures were calculated from random initial velocities. An initial 60 psec of restrained molecular dynamics (MD) in torsion angle space, with 15-fsec time steps, was followed by a 90-psec slow-cooling process for initial structures. At the final stage of the calculation, 30 psec (with 5-fsec time steps) of restrained molecular dynamics was performed in Cartesian coordinate space. After this initial calculation, structures were evaluated for convergence and accepted on the basis of their overall energy potentials and the number of NOE (>0.5 Å) and dihedral (>5.0°) violations. To observe the effect of RDCs, the SP structure calculations were also performed in the absence of RDCs.

The lowest-energy structures were selected and subjected to a gentle refinement (1 psec of restrained molecular dynamics at 300 K) in XPLOR v. 3.843 (Brunger 1992). The purpose of this refinement was to maintain the proper chirality of phosphate oxygens and amino protons, which can be reversed in Cartesian space refinement protocols (Schultze and Feigon 1997). This refinement also assisted in the planarity of amino functional groups. The final ensemble was comprised of 17 structures for the SP-ISL structures both in the presence and absence of RDCs. The 20 WT-ISL RDC structures were also determined using this calculation protocol. The software program Insight II (Biosym) was used to generate the idealized A-form helix with the sequence r(GGUUCAACCU-AG GUUGAACC), which is identical in its first five base pairs to the WT-ISL sequence. All structures were viewed and analyzed using MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996).

[Note: Chemical shift data for the SP-ISL RNA have been deposited in BioMagResBank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu), entry code 5703. Coordinates for the WT-ISL and SP-ISL structures calculated with RDCs have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org), WT accession code 1NYZ SP accession code 1NZ1.]

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge D. Brow for helpful discussions; V. DeRose and L. Hunsicker for diastereomer purification protocols; T. Record, J. Cannon, and D. Felitsky for spectrophotometer measurement time and technical assistance; and NMRFAM staff for technical support. NMR studies were carried out at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison with support from the NIH Biomedical Technology Program and additional equipment funding from the University of Wisconsin, NSF Academic Infrastructure Program, NIH Shared Instrumentation Program, NSF Biological Instrumentation Program, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This work was supported by an NIH grant (GM65166) to S.E.B., a Molecular Biophysics Training Grant to N.J.R, a Biotechnology Training grant to R.J.J., and a University of Wisconsin Hilldale Fellowship to L.J.N. and S.E.B.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

CT, constant time

HETCOR, heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy

HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy

NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance

NOESY, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect

ppm, parts per million

RDC, residual dipolar coupling

TOCSY, total correlation spectroscopy

RMSD, root mean square deviation

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2199103.

REFERENCES

- Allain, F.H. and Varani, G. 1995. Divalent metal ion binding to a conserved wobble pair defining the upstream site of cleavage of group I self-splicing introns. Nucleic Acids Res. 23: 341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelin, M., Hessler, G., Kurz, G., Hacia, J.G., Dervan, P.B., and Kessler, H. 1998. Structure of a stereoregular phosphorothioate DNA/RNA duplex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5: 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brow, D.A. 2002. Allosteric cascade of spliceosome activation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36: 333–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A.T. 1992. X-PLOR (version 3.1) manual. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

- Brunger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., Delano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.-S., Kuszewki, J., Nilges, N., Pannu, N.S., et al. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system (CNS): A new software system for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Cryst. D 54: 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge, C.B., Tuschl, T.A., and Sharp, P.A. 1999. Splicing of precursors to mRNAs by the spliceosomes. In RNA world (eds. R.F. Gesteland et al.), Vol. II, pp. 525–560. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Butcher, S.E., Allain, F.H.T., and Feigon, J. 2000. Determination of metal ion binding sites within the hairpin ribozyme domains by NMR. Biochemistry 39: 2174–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore, G.M., Gronenborn, A.M., and Bax, A. 1998a. A robust method for determining the magnitude of the fully asymmetric alignment tensor of oriented macromolecules in the absence of structural information. J. Magn. Reson. 133: 216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore, G.M., Gronenborn, A.M., and Tjandra, N. 1998b. Direct structure refinement against residual dipolar couplings in the presence of rhombicity of unknown magnitude. J. Magn. Reson. 131: 159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C.A. and Guthrie, C. 2000. The question remains: Is the spliceosome a ribozyme? Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 850–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruse, W., Salisbury, S., Brown, T., Cosstick, R., Eckstein, F., and Kennard, O. 1986. Chiral phosphorothioate analogues of B-DNA. The crystal structure of Rp-d[Gp(s)CpGp(s)CpGp(s)C]. J. Mol. Biol. 192: 891–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann, T. and Feigon, J. 1997. Assignment methodology for larger RNA oligonucleotides: Application to an ATP-binding RNA aptamer. J. Biomol. NMR 9: 259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein, F. 1979. Phosphorothioate analogues of nucleotides. Acc. Chem. Res. 12: 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio, P. and Abelson, J. 1992. Thiophosphates in yeast U6 snRNA specifically affect pre-mRNA splicing in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 20: 3659–3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortner, D.M., Troy, R.G., and Brow, D.A. 1994. A stem/loop in U6 RNA defines a conformational switch required for pre-mRNA splicing. Genes & Dev. 8: 221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, C., Stec, W., Kobylanska, A., Hogrefe, R.I., Reynolds, M., and James, T.L. 1994. Structural study of a DNA • RNA hybrid duplex with a chiral phosphorothioate moiety by NMR: Extraction of distance and torsion angle constraints and imino proton exchange rates. Biochemistry 33: 11062–11072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, P.M., Sontheimer, E.J., and Piccirilli, J.A. 2000. Metal ion catalysis during exon-ligation step of nuclear pre-mRNA splicing: Extending the parallels between the spliceosome and group II introns. RNA 6: 199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntert, P., Mumenthaler, C., and Wuthrich, K. 1997. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 273: 283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.R., Hanson, P., and Pardi, A. 2000. Filamentous bacteriophage for aligning RNA, DNA, and proteins for measurement of nuclear magnetic resonance dipolar coupling interactions. Methods Enzymol. 317: 220–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppler, A., Nikstad, L.J., Allmann, A.M., Brow, D.A., and Butcher, S.E. 2002. Metal binding and base ionization in the U6 RNA intramolecular stem–loop structure. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9: 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaroszewski, J.W., Syi, J.-L., Maizel, J., and Cohen, J.S. 1992. Towards rational design of antisense DNA: Molecular modelling of phosphorothioate DNA analogues. Anti-Cancer Drug Design 7: 253–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker, F.M., Heus, H.A., Yip, P.F., Moors, E.H.M., and Pardi, A. 1996. A network of heterogeneous hydrogen bonds in GNRA tetraloops. J. Mol. Biol. 264: 968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wuthrich, K. 1996. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14:51–55, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, J.F. and Uhlenbeck, O.C. 1989. Synthesis of small RNAs using T7 RNA polymerase. Methods Enzymol. 180: 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, T.W. 1998. RNA–RNA interactions in nuclear pre-mRNA splicing. In RNA structure and function (eds. R. Simons and M. Grunberg-Manago), pp. 279–307. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Pecoraro, V.L., Hermes, J.D., and Cleland, W.W. 1984. Stability constants of Mg2+ and Cd2+ complexes of adenine nucleotides and thionucleotides and rate constants for formation and dissociation of MgATP and MgADP. Biochemistry 23: 5262–5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenger, W. 1984. Principles of nucleic acid structure. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Schultze, P. and Feigon, J. 1997. Chirality errors in nucleic structures. Nature 387: 668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibille, N., Pardi, A., Simorre, J.P., and Blackledge, M. 2001. Refinement of local and long-range structural order in theophylline-binding RNA using 13C–1H residual dipolar couplings and restrained molecular dynamics. JACS 123: 12135–12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slim, G. and Gait, M.J. 1991. Configurationally defined phosphorothioate-containing oligoribonucleotides in the study of the mechanism of cleavage of hammerhead ribozymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 19: 1183–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.S. and Nikonowicz, E.P. 2000. Phosphorothioate substitution can substantially alter RNA conformation. Biochemistry 39: 5642–5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer, E.J., Sun, S.G., and Piccirilli, J.A. 1997. Metal ion catalysis during splicing of pre-messenger RNA. Nature 388: 801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadkhan, S. and Manley, J.L. 2001. Splicing-related catalysis by protein-free snRNAs. Nature 413: 701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J.J. and Moore, P.B. 2001. A maximum likelihood method for determining DaPQ and R for sets of dipolar coupling data. J. Magn. Reson. 149: 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yean, S.L., Wuenschell, G., Termini, J., and Lin, R.J. 2000. Metal-ion coordination by U6 small nuclear RNA contributes to catalysis in the spliceosome. Nature 408: 881–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.T., Maroney, P.A., Darzynkiewicz, E., and Nilsen, T.W. 1995. U6 snRNA function in nuclear pre-mRNA splicing—A phosphorothioate interference analysis of the U6 phosphate backbone. RNA 1: 46–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweckstetter, M. and Bax, A. 2000. Prediction of sterically induced alignment in a dilute liquid crystalline phase: Aid to protein structure determination by NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122: 3791–3792. [Google Scholar]