Recent research suggests that members of the Baculoviridae family can be divided into two groups on the basis of their envelope fusion proteins (31). One group utilizes proteins related to GP64. Homologs of GP64 are also used by the thogotoviruses (27), a genus of the Orthomyxoviridae family. Members of the other group of baculoviruses utilize envelope fusion proteins related to a protein called LD130. LD130 has been shown to be related to the envelope protein of insect retroviruses in the genus Errantivirus (family Metaviridae) (24, 36). In this review, the evidence for these data is outlined and possible pathways of transfer, incorporation, and substitution are discussed.

The Baculoviridae is a large and diverse family of occluded viruses, with double-stranded DNA genomes, that are pathogenic for insects. They have been divided into two genera on the basis of their occlusion body morphology: the nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs) (34), which have large occlusion bodies containing numerous virions, and the granuloviruses (GVs) (48), which normally have single virions occluded within small granular occlusion bodies. In addition, baculoviruses are characterized by the development of two types of virions during their replication cycle, differing in the origin and composition of their envelopes (44). The budded virus (BV) type is enveloped with a modified host cell membrane as it exits from the infected cell. In contrast, the occluded virion (OV) type is enveloped in a membrane that is assembled in the nucleus prior to being surrounded by a proteinaceous occlusion body. The occluded form of the virus is highly stable and can persist for years outside the host insect. It is normally transmitted between insects via contamination of their diet. The BV type enters cells by an endocytic mechanism facilitated by the presence in its envelope of a virus-encoded, low-pH-activated envelope fusion protein. In contrast, the OV type lacks the envelope fusion protein of the BV type, and the mechanism by which it infects insect midgut cells is not well characterized but may be independent of low pH. Furthermore, studies on the BV type of Autographa californica multinucleocapsid NPV (AcMNPV) have shown that it is over 1,000-fold more infectious for cultured insect cells than the OV type of this virus (44) but is over 1,000-fold less infectious than the OV type when fed to insects (43). Therefore, the two types of baculovirus virions have envelopes derived from different sources and have different infectivity patterns, and they may enter cells by different mechanisms.

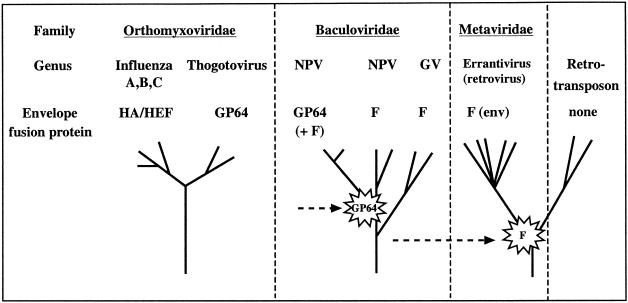

In earlier investigations of baculovirus biology, a protein called GP64 was identified as the envelope fusion protein of AcMNPV and its close relatives (2, 3, 42, 47). Subsequently, it was discovered that GP64 is closely related (∼30% identity at the amino acid level) to the envelope fusion protein encoded by members of the genus Thogotovirus (family Orthomyxoviridae), which are pathogenic for ticks and can also infect vertebrates (22, 27, 29, 33). This indicated that an envelope fusion protein either had been transferred between a minus-sense RNA virus and a double-stranded DNA virus or was acquired independently by each of these viruses from another source, such as a conserved host gene (29) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Distribution of envelope fusion protein homologs. Three virus families and a retrotransposon are indicated. Below each viral family are listed the genera in the family, and below that is shown the category of the envelope fusion protein. The category encompassing baculovirus LD130, SE8, OP21, AC23, etc., is called the F protein group in accordance with the convention of Westenberg et al. (46). A schematic representation of the phylogenetic relationships (not to scale) of the genera is shown at the bottom of the figure. The horizontal dashed arrows show possible pathways of envelope fusion protein exchange. The GP64 arrow is not connected, reflecting the possibility that gp64 entered a baculovirus lineage during a coinfection with a baculovirus and a thogotovirus or that it entered both lineages independently via recombination with a host-encoded gp64 homolog. Abbreviations: HA, hemagglutinin protein; HEF, hemagglutinin-esterase-fusion protein.

MANY BACULOVIRUSES LACK GP64 AND LIKELY USE LD130 HOMOLOGS AS THEIR ENVELOPE FUSION PROTEIN

The first three baculovirus genomes that were sequenced were all found to contain a gene encoding GP64 (reviewed in references 14 and 15). However, the subsequently obtained complete genome sequences of both NPVs and GVs were all found to lack genes encoding GP64 homologs (1, 5, 12, 13, 17, 21). Analysis of the Lymantria dispar (gypsy moth) multicapsid NPV (LdMNPV) genome, which does not encode a gp64 homolog, led to the identification of a single open reading frame (ORF), called ld130, encoding a protein with the predicted properties of a membrane protein, including signal and transmembrane domains and N-linked glycosylation sites (21). Subsequent analyses demonstrated that LD130 behaves as an envelope fusion protein in that it localized to the membranes of cells infected with Lymantria dispar multinucleocapsid NPV or transfected with ld130, and in the latter instance, a reduction in pH resulted in membrane fusion (31). Similar data were obtained for a homolog of ld130, se8, from a multinucleocapsid NPV of Spodoptera exigua (18). Members of this group of envelope fusion proteins have many of the properties of fusion proteins of a number of viruses that infect vertebrates. They appear to be cleaved by a cellular enzyme at a furin-like cleavage site (18, 46), and they are predicted to contain a coiled-coil region (36), suggesting that they may form structures of higher order similar to those found in many other viral fusion proteins (see, e.g., references 7 and 37). They have been called the baculovirus F (fusion) proteins (46).

GP64-CONTAINING BACULOVIRUSES ALSO ENCODE HOMOLOGS OF LD130 (BACULOVIRUS F PROTEIN)

Surprisingly, analysis of the completed baculovirus genome sequences has revealed that they all encode homologs of the baculovirus F protein, including those that appear to utilize GP64 as their envelope fusion protein. In addition, the baculovirus GP64 homologs are all closely related (>74% amino acid sequence identity), whereas the baculovirus F protein family is very diverse (20 to 40% sequence identity) and is found in both NPVs and GVs (Fig. 1). Therefore, it has been suggested that gp64 was incorporated relatively recently into the genome of a baculovirus, where it displaced the envelope fusion function of the baculovirus F homolog (31) (Fig. 1). This likely contributed to the evolution of viruses such as AcMNPV and its close relatives, which depend on GP64 as their envelope fusion protein. However, the fact that baculovirus F protein homologs are retained by gp64-containing viruses, but appear to be unable to act as fusion proteins, suggests that they perform other essential functions (32). In addition, attempts to delete the entire coding region of one such gene were unsuccessful (G. F. Rohrmann, unpublished data). We have distinguished these protein types as baculovirus Fa proteins (fusion competent) and Fb proteins (not fusion competent).

Further evidence for the adaptability of baculoviruses was provided by a recent report showing that a baculovirus lacking gp64 could utilize the envelope fusion protein of vesicular stomatitis virus as its fusion protein. Therefore, the ability of baculoviruses to enter cells appears to be accommodated by a variety of different envelope proteins (25).

BACULOVIRUS F PROTEIN HOMOLOGS ARE THE ENVELOPE PROTEINS OF INSECT RETROVIRUSES

The similarity between long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons and retroviruses has long been noted (6, 39, 49). A major difference between these retroelements is that the former do not encode an envelope protein. Consequently, although retrotransposons can move and amplify within organisms, their ability to be transmitted to other organisms is limited, and they are not infectious. Recently, two reports have provided evidence that a baculovirus F progenitor was the source of the envelope protein gene that resulted in the conversion of a gypsy-like noninfectious retrotransposon of insects into a retrovirus (24, 36). These insect retroviruses have been named the errantiviruses (4), and 13 species have been identified (40). One of these viruses has been shown to be infectious (20, 38), and when the gene encoding its predicted envelope protein was incorporated into the Moloney murine leukemia virus genome, that virus was able to infect Drosophila cells (41). The relatedness of the insect retrovirus env gene and the baculovirus F homologs likely reflects more than a fortuitous relationship between these two viruses. This is indicated in a study showing that an insect retrovirus called TED integrates into a baculovirus genome (8, 26). TED is present as a midrepetitive element (about 50 copies/genome) in an AcMNPV host, Trichoplusia ni (9). It is capable of transposition from the insect into the baculovirus genome; it encodes a full complement of retrovirus ORFs, including an env gene (30) that is related to the baculovirus F gene; and it is able to produce virus-like particles (23). A key feature of this relationship likely evolved because of the remarkable ability of baculoviruses to express genes at very high levels. This feature of their life cycle forms the basis of their widespread utility as expression vectors and appears to be due to the fact that they encode an RNA polymerase (11). This polymerase recognizes a novel promoter sequence (DTAAG) (35) that is found in the TED LTR as a palindrome. Late in the baculovirus infection cycle, mRNA is expressed from these LTRs at high levels (9). Therefore, integration into a baculovirus genome may reflect a strategy to exploit baculovirus late-gene expression to hyperexpress the integrated retrovirus genome. This could result in the production of a mixture of retrovirus particles and occluded baculoviruses containing integrated retroviruses. It has been suggested that in insects with fatal baculovirus infections, this may provide retroviruses such as TED with a two-pronged method of escape: they could survive by integrating into baculovirus genomes or as infectious virus particles, similar to those observed for other gypsy-like elements (36). The evolution of this relationship between a baculovirus and a primordial LTR-type retrotransposon provides a clear pathway, via DNA recombination, for the transposable element to incorporate the baculovirus F homolog into its genome, thereby converting it into an infectious retrovirus. Indeed, the evolutionary analyses of the envelope proteins of the errantiviruses suggest that the incorporation of the envelope protein gene into a transposable element was a monophyletic event (24). Furthermore, such an interaction may not be confined to the Baculoviridae, as it has been suggested that it may have occurred between transposable elements and other enveloped viruses on several occasions (7a, 24).

It may be significant that evidence for transfer and incorporation of the homologs of gp64 and baculovirus F genes is found among viruses pathogenic for invertebrates (ticks and insects). It is likely that invertebrate organisms, their viruses, and transposable elements proliferated and developed ancient relationships that predate the evolution of most vertebrate lineages. As vertebrates evolved, they would have provided new hosts for existing invertebrate viruses. However, whereas related patterns of structure and function have been suggested for viral envelope fusion proteins from different vertebrate viruses (7, 10, 16, 19, 28, 37, 45), clear evidence of such relatedness from primary sequence data appears to be confined to viruses that are pathogenic for arthropods. The preservation of primary sequence similarity may result from the absence of an adaptive immune response in the invertebrate hosts. In vertebrate viruses, the exposed position of envelope fusion proteins on the virion surface and the critical role they often play in virion attachment and cell entry make them prime targets for the adaptive immune response. This has resulted in a continuous and intense selective pressure on the proteins to retain their critical function yet evade the host immune response. This can be accomplished by changes in the primary sequence that preserve function but alter antigenicity. In contrast, arthropods lack adaptive immunity, and many insect hosts are short lived, resulting in an absence of this type of selective pressure. This may have led to the preservation of the primary sequence similarity, which allows determination of the relatedness of these proteins among different viruses of invertebrates.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the NSF (9982536) and by contributions from Lawrence and Margaret Noall. This review was written in part with support from a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science travel grant.

The gracious hosting of G.F.R. by Y. Matsuura, T. Miyazawa, and their colleagues during this travel grant is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

This is technical report no. 11876 from the Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afonso, C. L., E. R. Tulman, Z. Lu, C. A. Balinsky, B. A. Moser, J. J. Becnel, D. L. Rock, and G. F. Kutish. 2001. Genome sequence of a baculovirus pathogenic for Culex nigripalpus. J. Virol. 75:11157-11165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blissard, G. W., and G. F. Rohrmann. 1989. Location, sequence, transcriptional mapping, and temporal expression of the gp64 envelope glycoprotein gene of the Orgyia pseudotsugata multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 170:537-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blissard, G. W., and J. R. Wenz. 1992. Baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to mediate pH-dependent membrane fusion. J. Virol. 66:6829-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeke, J. D., T. Eickbush, S. B. Sandmeyer, and D. F. Voytas. 2000. Family Metaviridae, p. 359-367. In M. H. V. van Regenmortel, C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wickner (ed.), Virus taxonomy: 7th report of the International Congress on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 5.Chen, X., W. IJkel, R. Tarchini, X. Sun, H. Sandbrink, H. Wang, S. Peters, D. Zuidema, R. Lankhorst, J. Vlak, and Z. Hu. 2001. The sequence of the Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 82:241-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doolittle, R. F., and D. F. Feng. 1992. Tracing the origin of retroviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 176:195-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckert, D. M., and P. S. Kim. 2001. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:777-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Eickbush, T. H., and H. S. Malik. 2002. Origins and evolution of retrotransposons, p. 1111-1144. In N. L. Craig, R. Craigie, M. Gellert, and A. M. Lambowitz (ed.), Mobile DNA II. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Friesen, P. D., and M. S. Nissen. 1990. Gene organization and transcription of TED, a lepidopteran retrotransposon integrated within the baculovirus genome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:3067-3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friesen, P. D., W. C. Rice, D. W. Miller, and L. K. Miller. 1986. Bidirectional transcription from a solo long terminal repeat of the retrotransposon TED: symmetrical RNA start sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:1599-1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallaher, W. R. 1996. Similar structural models of the transmembrane proteins of Ebola and avian sarcoma viruses. Cell 85:477-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarino, L. A., B. Xu, J. Jin, and W. Dong. 1998. A virus-encoded RNA polymerase purified from baculovirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 72:7985-7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto, Y., T. Hayakawa, Y. Ueno, T. Fugita, Y. Sano, and T. Matsumoto. 2000. Sequence analysis of the Plutella xylostella granulovirus genome. Virology 275:358-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayakawa, T., R. Ko, K. Okano, S. Seong, C. Goto, and S. Maeda. 1999. Sequence analysis of the Xestia c-nigrum granulovirus genome. Virology 262:277-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayakawa, T., G. F. Rohrmann, and Y. Hashimoto. 2000. Patterns of genome organization and content in lepidopteran baculoviruses. Virology 278:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herniou, E. A., T. Luque, X. Chen, J. M. Vlak, D. Winstanley, J. S. Cory, and D. R. O'Reilly. 2001. Use of whole genome sequence data to infer baculovirus phylogeny. J. Virol. 75:8117-8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughson, F. M. 1997. Enveloped viruses: a common mode of membrane fusion? Curr. Biol. 7:565-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IJkel, W. F. J., E. A. van Strien, J. G. M. Jeldens, R. Broer, D. Zuidema, R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1999. Sequence and organization of the Spodoptera exigua multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 80:3289-3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IJkel, W. F. J., M. Westernberg, R. W. Goldbach, G. W. Blissard, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2000. A novel baclovirus envelope fusion protein with a proprotein convertase cleavage site. Virology 274:30-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi, S. B., R. E. Dutch, and R. A. Lamb. 1998. A core trimer of the paramyxovirus fusion protein: parallels to influenza virus hemagglutinin and HIV-1 gp41. Virology 248:20-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, A., C. Terzian, P. Santamaria, A. Pelisson, N. Purd'homme, and A. Bucheton. 1994. Retroviruses in invertebrates: the gypsy retrotransposon is apparently an infectious retrovirus of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1285-1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuzio, J., M. N. Pearson, S. H. Harwood, C. J. Funk, J. T. Evans, J. Slavicek, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1999. Sequence and analysis of the genome of a baculovirus pathogenic for Lymantria dispar. Virology 253:17-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leahy, M., J. Dessens, F. Weber, G. Kochs, and P. Nuttall. 1997. The fourth genus in the Orthomyxoviridae: sequence analyses of two Thogoto virus polymerase proteins and comparison with influenza viruses. Virus Res. 50:215-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerch, R. A., and P. D. Friesen. 1992. The baculovirus-integrated retrotransposon TED encodes gag and pol proteins that assemble into viruslike particles with reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 66:1590-1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malik, H. S., S. Henikoff, and T. H. Eickbush. 2000. Poised for contagion: evolutionary origins of the infectious abilities of invertebrate retroviruses. Genome Res. 10:1307-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangor, J. S., S. A. Monsma, M. C. Johnson, and G. W. Blissard. 2001. A GP64-null baculovirus pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G protein. J. Virol. 75:2544-2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, D. W., and L. K. Miller. 1982. A virus mutant with an insertion of a copia-like transposable element. Nature (London) 299:562-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morse, M. A., A. C. Marriott, and P. A. Nuttall. 1992. The glycoprotein of Thogoto virus (a tick-borne orthomyxo-like virus) is related to the baculovirus glycoprotein gp64. Virology 186:640-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mothes, W., A. L. Boerger, S. Narayan, J. M. Cunningham, and J. A. Young. 2000. Retroviral entry mediated by receptor priming and low pH triggering of an envelope glycoprotein. Cell 103:679-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nuttall, P. A., M. A. Morse, L. D. Jones, and A. Portela. 1995. Adaptation of members of the Orthomyxoviridae family to transmission by ticks, p. 416-425. In A. J. Gibbs, C. H. Calisher, and F. García-Arenal (ed.), Molecular basis of virus evolution. Cambridge University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 30.Ozers, M. S., and P. Friesen. 1996. The Env-like open reading frame of the baculovirus-integrated retrotransposon TED encodes a retrovirus-like envelope protein. Virology 226:252-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson, M. N., C. Groten, and G. F. Rohrmann. 2000. Identification of the Lymantria dispar nucleopolyhedrovirus envelope fusion protein provides evidence for a phylogenetic division of the Baculoviridae. J. Virol. 74:6126-6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson, M. N., R. Russell, and G. F. Rohrmann. 2001. Characterization of a baculovirus encoded protein that is associated with infected-cell membranes and budded virions. Virology 291:22-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Portela, A., L. D. Jones, and P. Nuttall. 1992. Identification of viral structural polypeptides of Thogoto virus (a tick-borne orthomyxo-like virus) and functions associated with the glycoprotein. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2823-2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rohrmann, G. F. 1999. Nuclear polyhedrosis viruses, p. 146-152. In R. G. Webster and A. Granoff (ed.), Encyclopedia of virology, 2nd ed. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 35.Rohrmann, G. F. 1986. Polyhedrin structure. J. Gen. Virol. 67:1499-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohrmann, G. F., and P. A. Karplus. 19 February 2001, posting date. Relatedness of baculovirus and gypsy retrotransposon envelope proteins. BMC Evol. Biol. 1:1. [Online.] http://www.biomedcentral.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skehel, J., and D. Wiley. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:531-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song, S. U., M. Kurkulos, J. D. Boeke, and V. G. Corces. 1997. Infection of the germ line by retroviral particles produced in the follicle cells: a possible mechanism for the mobilization of the gypsy retroelement of Drosophila. Development 124:2789-2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Temin, H. M. 1980. Origin of retroviruses from cellular moveable genetic elements. Cell 21:599-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terzian, C., A. Pélisson, and A. Bucheton. 10 August 2001, posting date. Evolution and phylogeny of insect endogenous retroviruses. BMC Evol. Biol. 1:3. [Online.] http://www.biomedcentral.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teysset, L., J. C. Burns, H. Shike, B. L. Sullivan, A. Bucheton, and C. Terzian. 1998. A Moloney murine leukemia virus-based retroviral vector pseudotyped by the insect retroviral gypsy envelope can infect Drosophila cells. J. Virol. 72:853-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volkman, L. E., P. A. Goldsmith, R. T. Hess, and P. Faulkner. 1984. Neutralization of budded Autographa californica NPV by a monoclonal antibody: identification of the target antigen. Virology 133:354-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volkman, L. E., and M. D. Summers. 1977. Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: comparitive infectivity of the occluded, alkali-liberated, and nonoccluded forms. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 30:102-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Volkman, L. E., M. D. Summers, and C.-H. Hsieh. 1976. Occluded and nonoccluded nuclear polyhedrosis virus grown in Trichoplusia ni: comparative neutralization, comparative infectivity, and in vitro growth studies. J. Virol. 19:820-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weissenhorn, W., A. Dessen, L. J. Calder, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1999. Structural basis for membrane fusion by enveloped viruses. Mol. Membr. Biol. 16:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westenberg, M., H. Wang, W. F. J. IJkel, R. W. Goldbach, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2002. Furin is involved in baculovirus envelope fusion protein activation. J. Virol. 76:178-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitford, M., S. Stewart, J. Kuzio, and P. Faulkner. 1989. Identification and sequence analysis of a gene encoding gp67, an abundant envelope glycoprotein of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 63:1393-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winstanley, D., and D. O'Reilly. 1999. Granuloviruses, 2nd ed. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 49.Xiong, Y., and T. H. Eickbush. 1990. Origin and evolution of retroelements based upon their reverse transcriptase sequences. EMBO J. 9:3353-3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]