Abstract

Translation is initiated within the RNA of the hepatitis C virus at the internal ribosome entry site (IRES). The IRES is a 341-nucleotide element that contains a four-way helical junction (IIIabc) as a functionally important element of the secondary structure. The junction has three additional, nonpaired nucleotides at the point of strand exchange on one diagonal. We have studied the global conformation and folding of this junction in solution, using comparative gel electrophoresis and steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer. In the absence of divalent metal ions, the junction adopts an extended-square structure, in contrast to perfect four-way RNA junctions, which retain coaxial helical stacking under all conditions. The IIIabc junction is induced to fold on addition of Mg2+, by pairwise coaxial stacking of arms, into the conformer in which the unpaired bases are located on the exchanging strands. Fluorescence lifetime measurements indicate that in the presence of Mg2+ ions, the IIIabc junction exists in a dynamic equilibrium comprising approximately equal populations of antiparallel and parallel species. These dynamic properties may be important in mediating interactions between the IRES and the ribosome and initiation factors.

Keywords: RNA structure, translation, RNA folding, fluorescence, FRET

INTRODUCTION

Translation in eukaryotes is normally initiated by the association of proteins with the capped 5′ terminus of mRNA, thereby recruiting the small ribosomal subunit. However, in some cases, translation can be initiated internally, when there is a specialized RNA structure called an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). These elements have been found in an increasing number of viral RNAs and a few eukaryotic mRNAs, and provide a mechanism that is independent of a capped 5′ terminus. One of the best-studied examples is found in the hepatitis C virus (HCV), a human pathogen transmitted by direct contact with blood. HCV is a single-stranded (+)-strand RNA (9500 nucleotides) virus of the flaviviridae family that is a cause of non-A, non-B hepatitis (Alter et al. 1989; Choo et al. 1989) and is associated with liver cancer in a proportion of patients with chronic infection (Simonetti et al. 1992; Liang et al. 1993; De Mitri et al 1995).

The HCV IRES is contained within the 5′-untranslated region upstream of a gene encoding a large polyprotein. Translation is initiated by the binding of eIF3 and the small ribosomal subunit directly to the IRES, which is located 5′ to the initiator codon. The 341-nucleotide IRES is highly conserved and has a complex secondary structure (Brown et al. 1992; Honda et al. 1996), shown schematically in Figure 1A. It contains the four-way 2HS22HS1 (Lilley et al. 1995) junction IIIabc (Fig. 1B). Such junctions have a major role in the organization of tertiary structure in autonomously folding RNA molecules, such as the nucleolytic ribozymes. The position of junction IIIabc suggests that it is likely to exert an important influence on the global structure of the IRES, and it has been shown to be closely involved in binding eIF3 (Sizova et al. 1998) and the 40S ribosomal subunit (Kolupaeva et al. 2000).

FIGURE 1.

Junction IIIabc of the HCV IRES, and its global conformation. (A) Schematic of the secondary structure of the IRES, with junction IIIabc circled. (B) The local sequence of the junction IIIabc. For the conformational analysis, we have extended the arms, and also created a perfect 4H junction by removal of the unpaired nucleotides. (C) The sequence of the junction used in FRET experiments. All four arms comprise 12 bp with no imperfections, with the natural sequence preserved to the maximum distance in each case – the same central sequences were used in the electrophoresis experiments. We denote the helical arms in both junctions as A, B, C, and S, corresponding to the helices of stem loops III a–c, and the main domain III helix [here called S (= starred) to be consistent with the use of helix III* in Keift et al. (2002)] in the IRES RNA. FRET vectors are named according to the helical arms carrying the fluorescein and Cy3 fluorophores, in that order; the example shown is the BC vector.

The folding characteristics of perfectly base-paired (4H) four-way RNA junctions are well established (Duckett et al. 1995; Walter et al. 1998a), but the IRES junction contains three formally unpaired nucleotides at the point of strand exchange. The effect of unpaired bases has not been studied previously, but is expected to exert a significant influence on the global conformation. A crystal structure of an RNA related to the IIIabc junction has been solved recently (Kieft et al. 2002). In the present study, we have examined the conformation of the junction in solution with a parallel analysis of the 4H junction derived by removal of the unpaired nucleotides. In particular, we have used fluorescence methods that reveal an important dynamic character of the IRES IIIabc junction.

RESULTS

Global structure of the IRES junction analyzed by electrophoresis

We have analyzed the global structure of the IIIabc junction using comparative gel electrophoresis (Gough and Lilley 1985; Cooper and Hagerman 1987; Duckett et al. 1988 Duckett et al. 1995). In this approach, we compare the electrophoretic mobility of the six possible species generated from a given four-way junction (loaded in a standard order), having two long (40 bp) and two short (10 bp) helical arms (for review, see Lilley 2000). These have been produced by chemical synthesis and comprise ribonucleotides over the junction-proximal 8 bp of each helical arm, and the remainder is made of deoxyribonucleotides. They are named according to the long arms; thus, the species AC has long A and C arms, and short B and S arms, for example. The results are analyzed on the well-established assumption that the mobility is proportional to the angle subtended between the long arms. Throughout the study, we have compared the natural sequence of the IIIabc junction with its formally unpaired bases on two exchanging strands (i.e., a 2HS22HS1 junction), with the perfect 4H junction derived by removal of these additional nucleotides.

The global conformation in the absence of added metal ions

We initially examined the conformation of the two junctions in the absence of added metal ions. We compared the electrophoretic mobility of the six long-short species for both junctions in a 10% polyacrylamide gel at room temperature (Fig. 2A). The two junctions give very different patterns of mobilities, showing the influence of the additional unpaired bases on the global structure. The 4H junction gives a fast-slow-slow-slow-slow-fast pattern that is typical of perfect RNA four-way junctions in the absence of added metal ions (Duckett et al. 1995; Walter et al. 1998b), and can be interpreted in terms of a structure in which the arms are coaxially stacked in pairs (A on B and C on S), where the two axes are approximately perpendicular. In contrast, the natural junction gives a slow-fast-slow-slow-fast-slow pattern. This is exactly the pattern that is given by 4H DNA junctions in the absence of added metal ions (Duckett et al. 1988, 1990), and is explained in terms of a junction in which there is no helical stacking, and the arms point toward the corners of a square. The slower mobilities of the quasi-linear species AC and BS in the IRES junction compared with the AB and CS species of the 4H junction are indicative of considerable conformational averaging in the flexible, open IRES junction.

FIGURE 2.

The global conformation of junction IIIabc analyzed by comparative gel electrophoresis. We compare the electrophoretic mobility of the six species having two long arms (giving their names to the species) and two short arms, and analyze the data with the expectation that the mobility will depend on the angle subtended between the long arms (Duckett et al. 1988; Lilley 2000). In each case, we compare the mobilities of the six long-short species for the natural IRES junction (tracks 1–6) and its 4H derivative (tracks 7–12). The data have been interpreted in terms of the models indicated adjacent to the gels (left, IRES junction; right 4H junction). The analysis has been performed in the absence of added divalent ions (A) and in 1 mM Mg2+ (B).

We have never observed the slow-fast-slow-slow-fast-slow pattern with perfect 4H RNA junctions, which retain coaxial pairwise helical stacking even in the absence of added metal ions (Duckett et al. 1995; Walter et al. 1998a,b). By comparison, all DNA 4H junctions adopt the open structure at low-salt concentrations (Duckett et al. 1988; Clegg et al. 1994). The equilibrium between stacked and unstacked forms of the junction will reflect the free energy balance of base stacking versus electrostatic repulsion, with the former becoming dominant as counterion screening reduces the latter. The additional bases of the IRES junction could affect the position of equilibrium either by destabilizing the stacked conformation, or perhaps by stabilizing the unstacked structure at low salt concentrations due to increased conformational flexibility.

Folding of the junctions on addition of Mg2+ ions

The comparative gel electrophoresis experiments were repeated in buffer containing 1 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 2B). Under these conditions, the pattern of migration shown by the 4H junction was found to change into a fast-intermediate-slow-slow-intermediate-fast pattern, indicating some rotation into an antiparallel structure (while retaining the same A on B and C on S stacking partners). This is typical for perfect 4H RNA junctions in general (Duckett et al. 1995; Walter et al. 1998b). Trace bands for the AC and BS species at the slow position may indicate some 90° species in slow exchange.

The natural IRES junction exhibits a marked change in global structure as a result of the addition of Mg2+. The pattern can be described as a slightly distorted fastslow-slow-slow-slow-fast pattern, for which the simplest interpretation is a coaxially stacked structure with a 90° angle between the axes (however, see discussion below). The stacking conformer (A on B and C on S) is the same as that formed by the perfect 4H junction under all conditions. The equivalence of the four slow species is slightly broken by the faster mobility of the BS species, suggesting that the additional unpaired bases may distort the symmetry of the structure to some extent. We have found that this distortion is accentuated when the junction is folded in the presence of hexammine cobalt (III) ions (data not shown).

The global structure analyzed by FRET

FRET provides an alternative solution approach that requires no assumptions about electrophoretic mobilities. We measure the efficiency of energy transfer between donor (fluorescein) and acceptor (Cy3) fluorophores attached to helical ends of the IRES IIIabc or derived 4H junctions having four arms each of 12 bp (Fig. 1C). Efficiency is inversely related to the sixth power of the distance between the fluorophores (Förster 1948).

The values of FRET efficiency for six end-to-end vectors for the natural IRES junction are presented graphically in Figure 3; the results are in good agreement with the gel electrophoresis. The relative values of EFRET in the absence of added metal ions (Fig. 3A) are fully consistent with an open square, in which the longest distances (i.e., lowest EFRET) should be the diagonal species CA and BS. Addition of Mg2+ alters the pattern of efficiencies (Fig. 3B), such that the lowest values of EFRET are now found for the vectors BA and CS, which are the end-to-end vectors for the stacked pairs of helices. Hence, this confirms the stable stacking conformer for this junction. The slightly lower EFRET for the CA and BS vectors could indicate a slightly antiparallel rotation. We have also measured the FRET efficiencies for the perfect 4H junction in the presence of Mg2+ (Fig. 3C). The results suggest a pronounced antiparallel structure, such that there is little distinction between the longer distances, with the short vectors (AS and BC) approaching FRET efficiencies of 0.5.

FIGURE 3.

Steady-state FRET analysis of the conformation and folding of the IRES junction. For these experiments, we use junctions with arms of 12 bp in length (see example in Fig. 1C), in which two arms are terminally 5′-labeled with fluorescein (donor) and Cy3 (acceptor), and measure the energy transfer between them. We have measured FRET efficiency (EFRET) for six vectors, corresponding to different end-to-end distances. The patterns of efficiencies correspond well to the global structures deduced from gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2). (A,B) Histograms of the FRET efficiencies for the six vectors for the IRES junction in 0 mM (A) and 10 mM (B) Mg2+. (C) FRET efficiencies for the 4H junction in 10 mM Mg2+.

Analysis of ion-induced folding

The course of the ion-induced folding of the RNA junctions can be followed by the change in FRET efficiency as a function of Mg2+ concentration. These data can be fitted to a two-state model of folding, from which the half-Mg2+ concentration ([Mg2+]½) and cooperativity of ion binding (Hill coefficient, n) can be calculated (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Two-state model fits of FRET efficiency data for ion-induced folding of IRES and 4H junctions as a function of Mg2+ concentration

| Vector | [Mg]1/2/μM | Error | n | Error |

| 4H junction | ||||

| BC | 132 | 61 | 0.8 | 0.07 |

| SB | 176 | 114 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| IRES junction | ||||

| CS | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| BA | 3 | 2 | 0.56 | 0.07 |

| AC | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.83 | 0.04 |

| BS | 6 | 3 | 2.9 | 0.7 |

| AS | 4 | 2 | 0.68 | 0.06 |

| BC | 3 | 1 | 0.60 | 0.04 |

Values of [Mg]1/2 and Hill coefficients (n) for individual end-to-end vectors calculated from the fits shown in Figure 4, with standard errors.

Like all perfect 4H RNA junctions studied, that derived from the HCV IRES by removal of the unpaired bases retains pairwise coaxial helical stacking even in the absence of added salts, but undergoes a rotation into an antiparallel conformation induced by the binding of divalent metal ions. Folding is quite symmetrical, as the curves of increase and decrease in FRET efficiency for the BC and SB vectors, respectively, are nearly mirror images (Fig. 4A). The data are well fitted to the two-state model with a [Mg2+]1/2 = 150 μM and n = 0.9. These values are very similar to those for other 4H junctions studied (Walter et al. 1998a), such as that derived from the hairpin ribozyme (Walter et al. 1998b).

FIGURE 4.

Ion-induced folding of the junctions studied by the change in FRET efficiency as a function of Mg2+ concentration for particular vectors. (A) 4H junction: BC (open circle); SB (closed circle). (B) IRES junction: BA (closed circle); CS (open circle); BS (closed triangle); AC (open triangle); AS (closed square); BC (open square). The data have been fitted to two-state models (lines), from which [Mg]1/2 and Hill coefficients (n) have been calculated and given in Table 1.

In view of the lower symmetry of the 2HS22HS1 junction of the natural HCV IRES sequence, we have studied the FRET efficiency of six end-to-end vectors (representing the six different end-to-end distances) as a function of Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 4B). We expected that the folding properties would be quite different from the 4H junction derived from it, as the natural junction adopts an open structure at low ionic concentration. Ion-induced folding therefore involves the formation of stacked helical arms in pairs and possibly rotation, rather than just a rotation of already-stacked arms. Two differences in the folding pattern are evident when compared with the 4H junction. First, folding of the natural junction is brought about by a significantly lower Mg2+ concentration, in the 1−6 μM range. This is closely similar to the folding of four-way DNA junctions (Fogg et al. 2001), which also undergo helical stacking as an integral part of the folding process. Second, the folding characteristics are different for the various end-to-end vectors. The approximately symmetrical structure of the fully folded junction separates the vectors into three pairs, which undergo nearly identical distance changes. However, although the initial and final efficiencies are similar within the pairs for any given titration, the shapes of the curves are not all identical, showing a reduced symmetry in the folding process. The BS vector stands out as markedly cooperative (n>2), although its complex folding is not well fitted by the two-state model (showing systematic deviations in residuals; data not shown), whereas the folding reported by most of the vectors corresponds to either noncooperative or even anticooperative two-state ion binding. These differences show that, in contrast to the simple two-state folding of a 4H RNA junction, that of the IRES junction is relatively complex with different parts of the junction undergoing subtly different structural transitions.

Multiple folded species contribute to FRET

The unusual folding properties of the natural IRES junction prompted us to consider to what extent the observed folded structure is dynamic, and whether or not the structure obtained by steady-state measurements might represent an average of two or more structures in dynamic exchange. Distances obtained from steady-state FRET measurements provide no information on contributing distributions of donor-acceptor distances. However, in reality, the observed distance may actually be a distribution with significant width, or there may be more than one conformation populated at equilibrium. We therefore turned to time-resolved measurements of energy transfer, to see whether multiple distance distributions might contribute the observed average FRET. There was a second reason for carrying out these measurements. Our electrophoretic and steady-state FRET measurements were interpreted most simply in terms of a nearly 90° stacked cross-conformation, with a small bias toward antiparallel rotation. However, a recent crystal structure of an equivalent junction was found to be in a strongly parallel conformation (Kieft et al. 2002). Therefore, we wondered whether antiparallel and parallel forms of the junction might coexist in free solution with properties that average to those of a 90° stacked form.

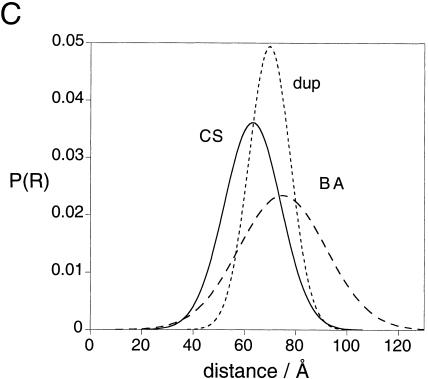

To answer these questions, we have used time-resolved fluorescence measurements, on the basis of the shortening of the excited state lifetime of the donor arising from energy transfer to the acceptor. Such measurements have provided valuable information of populations of species with different donor-acceptor lengths in solution, and have been used previously in other branched nucleic acids (Eis and Millar 1993; Yang and Millar 1996; Miick et al. 1997). We have made frequency-domain fluorescence lifetime measurements for the six end-to-end vectors of the folded natural IRES junction in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 5). The donor + acceptor-labeled samples have been compared with a single donor-labeled (A arm) junction, as all four ends share the same terminal 5′ CpC sequence, and comparison of two such donor controls revealed no distinguishable difference in fluorescence lifetime. We have measured the phase shift and demodulation of fluorescence emission as a function of the frequency of modulation of the excitation intensity (Fig. 5A). These data have been fitted to a variety of models that allow for energy transfer between donor and acceptor separated by various distances. The simplest model for donor-acceptor (D-A) energy transfer that we examined used a single Gaussian distribution of interfluorophore distances. Table 2A reports the best fit values of distance and half-width (full width at half maximum), and the corresponding range of values from a Bootstrap error analysis for each vector.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of D-A distance distributions by time-resolved fluorescence measurements. (A) Plots of phase shift and demodulation of the fluorescence emission of the CS (open circles) and SA (closed circles) vectors in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+ as a function of the frequency of intensity modulation of the excitation. The best fits of CS to a single distribution of D-A lengths and SA to two distributions are shown as solid lines. The single distribution fit of SA is also shown as a broken line. (B) The resulting residuals for the phase and modulation of the fits in part A are shown. A single Gaussian fit for CS is compared with the single- (SA-1G) and two- (SA-2G) Gaussian distribution fits to SA. (C) Single-Gaussian D-A distance distribution retrieved from the fit (Table 2A) for the duplex control (dotted line) and the stacked vectors, BA (dashed line), and CS (solid line). Areas are unity, lowering the heights of the wider distributions. (D) Two-Gaussian (2G) distance distributions for the BS vector (solid) as compared with a single-Gaussian (1G, dotted). Fit values are listed in Table 2, A and B. Areas for the two Gaussian distributions sum to unity; each distribution has an area of 0.5, corresponding to a 1:1 ratio of parallel (P) and antiparallel (AP) species. The area for the single-distance fit is unity. (E–H) Scatter diagrams showing the distribution of acceptable fits from Bootstrap error analysis. The scatter diagrams present the population of acceptable distances and half-widths. Nine hundred Bootstrap cycles are represented in each case. (E) Analysis for the single Gaussian fit for the CS vector. (F) Analysis for the single Gaussian fit for the SA vector. (G) Analysis for the two-Gaussian distance distribution (shorter distance, corresponding to the antiparallel conformer) for the SA vector. (H) Two-Gaussian distribution (longer distance, parallel conformer) for the SA vector.

TABLE 2.

Summary of fits to time-resolved fluorescence data for the IRES junction measured in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+

| A. Fits for individual vectors, using single distance distributions | |||

| Vector | Distance (range) | Half-width (range) | χ2 |

| Duplex | 69.8 (69.5–69.9) | 19.0 (16.3–20.1) | 7.5 |

| CS | 63.2 (63.0–63.3) | 26.0 (24.8–26.3) | 6.2 |

| BA | 74.9 (74.6–75.0) | 40.2 (37.1–40.6) | 7.7 |

| AC | 52.0 (51.9–52.6) | 38.4 (36.9–38.5) | 8.6 |

| BS | 51.4 (50.2–52.5) | 54.9 (52.8–57.1) | 12.9 |

| SA | 53.5 (53.4–54.7) | 47.5 (45.0–47.7) | 9.2 |

| BC | 46.1 (45.4–46.7) | 39.0 (38.0–40.0) | 11.7 |

| B. Fits using two distance distributions for nonstacked vectors (each fitted individually) | |||||

| Distance (range) | Half-width (range) | Distance (range) | Half-width (range) | ||

| Vector | Antiparallel | Parallel | χ2 | ||

| Distances are given in Å and distribution widths are reported as full width at half maximum. The range indicates the mean distance ± 1 standard deviation evaluated by Bootstrap analysis. | |||||

| (A) Phase and modulation data for the six vectors were fitted individually to a model based on a single Gaussian distribution of D-A distances in each case. The duplex was a 24-bp RNA corresponding to coaxially stacked A and B helices. | |||||

| (B) The data for the four nonstacked vectors were fitted to a model corresponding to a scissor-like rotation of the helical axes to give populations of parallel and antiparallel species. For each vector, two Gaussian distributions of D-A distances were used. For the fits shown a ratio of 1:1 was used. | |||||

| AC | 65.7 (65.0–66.8) | 28.6 (18.5–32.0) | 46.6 (46.0–47.3) | 14.5 (9.0–16.0) | 6.1 |

| BS | 76.5 (75.1–76.8) | 40.7 (20.6–45.6) | 48.4 (47.6–48.9) | 12.2 (6.8–12.7) | 6.2 |

| SA | 51.0 (50.3–51.5) | 15.0 (12.5–15.80) | 71.7 (70.7–73.7) | 68.4 (55.4–75.6) | 4.6 |

| BC | 46.2 (44.5–47.1) | 15.8 (9.1–16.1) | 57.2 (55.7–61.6) | 41.5 (25.7–45.6) | 8.3 |

The longest resulting distances are for the CS and BA vectors; these are the two vectors corresponding to the stacked helical pairs in the model derived from the electrophoretic and steady-state FRET data. These data are each well fitted by a single Gaussian distribution of D-A distances (Fig. 5A,B). These vectors are compared with a 24-bp RNA duplex, which acts as a model of a stacked pair of helical A and B arms, and the distributions are plotted in Figure 5C. Inclusion of a second distance distribution failed to improve the quality of the fit, and we conclude that CS and BA are stacked with no discernable contribution of additional stacking conformers or unstacked species. However, these D-A distances are slightly different from that for the control duplex, and the half-widths larger, suggesting that the coaxial stacking is not perfect, leading to greater flexibility. The possibility that these stacked vectors might better describe a skewed Gaussian was not borne out by fitting, which showed negligible improvement when asymmetry terms were included. The half-width is greater for the BA than the CS vector, indicating a greater mobility for the former, due to flexibility at the center or a population of the unstacked form. This is consistent with the greater cooperativity of ion-induced folding for the CS vector, suggesting a more stable coaxial stacking in 1 mM Mg2+, and is also consistent with a CS half-width similar to the duplex. Examination of the structure of the junction in the crystal shows that helices B and A are less well stacked, due to intercalation of the unpaired bases into the helix–helix interface, consistent with a BA vector that is longer and considerably more flexible than the duplex.

Whereas the BA and CS vectors define the stacked helices of the junction, the remaining four vectors characterize the angles between the axes of these helices; the junction can, in principle, undergo scissor-like rotations between parallel and antiparallel structures. Examination of the single-Gaussian distribution fits for these four vectors (Table 2A) show that their character is different from the two stacked vectors. The distances are shorter and the half-widths are all relatively wide (as compared with the duplex). The single-Gaussian fits to these data show higher values of χ2 and more systematic distribution of residuals (Fig. 5B), indicating generally poorer fits. There is also an increased correlation in parameters for these vectors, as shown in the Bootstrap analysis of the single-Gaussian fits of the CS and SA species (Fig. 5E,F). The distribution breadths, poorer fit quality, and strong parameter correlation led us to consider two distributions for the four nonstacked species.

We individually refitted the data for the AC, BS, SA, and BC vectors using two distance distributions. These four vectors fall into two oppositely correlated pairs of distances, one in which the shorter distances correspond to an antiparallel orientation (AS and BC), and the other in which they are associated with a parallel rotation (AC and BS). Given the established coaxial stacking of A on B and C on S arms, we took the ratio between parallel and antiparallel rotations to be constant. Fits were performed using various ratios of parallel:antiparallel, and the best fits were obtained when the ratio was 1:1 (Fig. 5A,B). This is shown in Table 2B with the Bootstrap-determined error ranges, and the distributions for the BS vector plotted in Figure 5D. In contrast to the single D-A distribution fits, the dual D-A distribution fits for these vectors significantly reduce the χ2 and improve the distribution of residuals (Fig. 5B) in a runs test. The parameter values are better determined and are less correlated (Fig. 5G,H). The two-Gaussian D-A distance fit for the SA vector, and a comparison of the residuals for the two models are shown in Figure 5, A and B. A global fit of all four vectors with linked ratio of parallel:antiparallel species gave similar results. We conclude that two distance distributions, corresponding to parallel and antiparallel conformations, better describe our data than a single broad distribution. We have simulated the data with varying proportions of the two conformations, and there was little difference in the quality of the fits over the proportion of antiparallel from 0.4 to 0.6.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that the additional, formally unpaired nucleotides found in the IIIabc junction of the HCV IRES confer a number of special folding properties on this four-way junction.

First, the junction adopts an open structure lacking pairwise coaxial stacking of arms at low-salt concentrations, in contrast to all perfect 4H RNA junctions studied, including that derived from the IRES junction. Second, the manner of ion-induced folding is significantly altered by the unpaired nucleotides of the IRES junction. The Mg2+ concentration required to fold the natural junction is two orders of magnitude lower than for the derivative 4H junction, and is close to that required to fold a DNA 4H junction. Clearly, the folding transition is quite different for the two RNA junctions, as one (natural IRES junction) involves the formation of the interhelical stacking interactions, whereas the other (4H) requires the rotation of pre-stacked helical pairs. Unsurprisingly, the folding process is rather more complex for the natural junction. Whereas the 4H junction folds as a very simple two-state process, comparison of the folding behavior for the six different end-to-end vectors of the natural junction shows variation in the ionic concentrations required to achieve folding, and in the observed cooperativity (apparent Mg2+ binding varies from anticooperative to highly cooperative for different vectors). The difference in behavior of the various end-to-end vectors must reflect the relative energetics of helix stacking and the interactions of the unpaired bases.

Perhaps most importantly, fluorescence lifetime studies show that the conformation of the natural IRES junction folded in the presence of Mg2+ is not a single state, but is better represented as a mixture of two conformations. These studies indicate that there is only a single predominant stacking conformer present, but the data are consistent with the presence of antiparallel and parallel forms of the junction, with an ~1:1 ratio (Fig. 6A). If these two species were in rapid equilibrium, such as to average measured properties, this would readily explain the electrophoretic pattern that appears to indicate a 90° crossed structure (Fig. 6B), and the slightly antiparallel stacked form deduced by steady-state FRET measurements.

FIGURE 6.

A dynamic structure for the HCV IRES IIIabc junction in solution. (A) The natural IRES junction adopts an unstacked, extended structure in the absence of divalent metal ions, in contrast to the 4H junction. On addition of magnesium ions, the structure is best described by an equilibrium mixture of antiparallel and parallel stacked forms of the junction. (B) A rapid exchange between the antiparallel and parallel forms explains the electrophoretic pattern observed in the presence of magnesium ions. The antiparallel structure gives the set of shaded species (as found in the folded 4H junction), whereas the parallel structure is predicted to give the fast-slow-intermediate-intermediate-slow-fast pattern. Rapid exchange would lead to the average pattern illustrated, which is closely similar to that predicted for a static stacked 90° form, and to that observed experimentally for the IRES junction (Fig. 2B left,). Right- and left-handed forms of each conformation are possible, and only the simplest transition is illustrated.

The structure of a double-junction form of the IRES IIIabc junction that has been solved recently by X-ray crystallography (Kieft et al. 2002) exhibits the same A on B and C on S stacking that we observe in solution, but the structure is almost perfectly parallel in the crystal. Our results indicate a parallel-antiparallel equilibrium in solution, but as both forms cannot be incorporated into a lattice, the equilibrium must be pulled one way or the other during the crystallization process. Clearly, the form obtained by Kieft et al. (2002) has been drawn into the parallel form, and may have been distorted even further in this direction than we observe in solution, as our time-resolved FRET measurements are not consistent with a side-by-side parallel conformation, in which the short donor-acceptor distances would result in efficiencies of energy transfer much higher than those calculated. It will be very interesting to learn to what extent the interactions of the unpaired bases observed in the crystal are preserved as the axes rotate relative to one another in solution. The results show that the dynamic solution data provide an important additional perspective on the structural data from the crystal, particularly in the case of a relatively malleable structure such as a helical junction. A precedent for this is set by a fourway RNA/DNA junction studied by Joyce and co-workers, who have crystallized both left- and right-handed forms (Nowakowski et al. 1999, 2000); this shows that another form of rotational variation is possible in helical junctions.

The structural flexibility of the IRES RNA may be important in the functional interaction with the ribosome. A cryo-electron microscopy reconstruction of this structure has been presented by Frank and co-workers (Spahn et al. 2001), and the helices assigned using a deleted version of the RNA. This suggests that the bound form of the RNA would be close to a 90° cross, with a small bias in the parallel direction. The unpaired central bases are probably important in allowing the RNA to adopt this conformation, consistent with mutational effects at these positions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Junction preparation

Ribo-oligonucleotides were synthesized using phosphoramidite chemistry (Beaucage and Caruthers 1981), as described in Wilson et al. (2001). Fluorescein and Cy3 fluorophores were attached at 5′ termini, as appropriate, during synthesis. The sequences of the four RNA strands for creating the FRET junction (and the core of the junctions used for comparative gel electrophoresis) were (a) CCCGCACACCGGAAUCGCCAGGGG, (b) CCCCUGGCGAUUU GGGCGGUCCGGG, (c) CCCGGACCGCCCCCGCAGACCAGG, and (s) CCUGGUCUGCGGAACCGGUGUGCGGG (Fig. 1C). For the 4H junction, the central U was omitted from the b strand and the central AA was omitted from the s strand. Junctions for comparative gel electrophoresis were constructed as described by Duckett et al (1995). They were formed by hybridizing four strands, one of which was radioactively [5′-32P]-labeled, to create two short arms and two long arms. The RNA core was extended by an additional 2 or 32 bases of DNA during the synthesis, creating 10-bp short arms and 40-bp long arms. Junctions were purified by electrophoresis in 8% polyacrylamide gels, and recovered from gel slices by electroelution, followed by precipitation with ethanol. RNA was resuspended in 90 mM Tris-borate (pH 8.3) buffer. For FRET experiments, junctions were resuspended in buffer treated with Chelex100 resin (Bio-Rad).

Comparative gel electrophoresis

Purified RNA–DNA junctions were loaded onto 10% polyacrylamide gels (19:1::acrylamide:bis) and electrophoresed in 90 mM Tris-borate (pH 8.3), 2 mM EDTA, or 1 mM Mg2+ (recirculated at >1 L/hr) at room temperature for 24 h at 130 V. Gels were dried onto Whatman 3MM paper and subjected to autoradiography at −70°C.

Steady-state fluorescence measurements

Fluorescence spectra were recorded at 4°C using an SLM-Aminco 8100 fluorimeter. Spectra were corrected for lamp fluctuations and instrumental variations, and polarization artifacts were avoided by setting excitation and emission polarizers crossed at 54.7°. Values of EFRET were measured using the acceptor normalization method (Clegg 1992). Data from magnesium ion titrations were analyzed on the assumption of a simple two-state model for ion-induced folding, in which the fraction of molecules in the folded state (α), is given by:

|

(1) |

where KA is the apparent association constant for magnesium ions and n is a Hill coefficient. Data were fitted to this equation by nonlinear regression. The magnesium ion concentration at which the transition is half complete ([Mg2+]1/2) is given by (1/KA)1/n.

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements

Time-resolved fluorescence lifetime measurements were performed using a K2-Digital Phase Fluorimeter (ISS, Inc.). Excitation at 488 nm was provided by a vertically polarized, argon ion laser (200 mW, Melles-Griot), intensity modulated at 25–38 frequencies between 4 and 300 MHz. The cross-correlation frequency was 400 Hz. Donor emission was measured using a 10-nm bandpass filter centered at 520 nm (520DF10, Omega Optical) to exclude scattered incident light and acceptor fluorescence, and a polarizer set at 54.7° to remove instrumental artifacts. Measurements were referenced to fluorescein in 10 mM NaOH, with a lifetime of 4.05 nsec. A minimum of 6 and a maximum of 12 measurements were performed at each frequency, with data collection terminating if the phase error was below 0.1 degree and the modulation error was below 0.002.

The decay of the fluorescence intensity (IDA) of a donor in the presence of an acceptor at distance r with time is given by (Lakowicz 1999):

|

(2) |

where τDi is the ith fluorescent lifetime (fraction αDi and R0 is the Förster length for the donor-acceptor fluorophore pair. For a distribution of donor-acceptor lengths [P(R)], the decay of intensity with time is given by:

|

(3) |

If there are n distributions, an additional summation is required:

|

(4) |

in which fn is the fraction of the nth distribution. In the frequency domain, sine (Nω) and cosine (Dω) transforms are taken:

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

in which ω is the modulation frequency (rad s−1). These are related to the phase shift [φ(ω)] and modulation [m(ω)] by:

|

(7) |

and

|

(8) |

Phase shift and modulation data were analyzed with the parameter estimation program CFS_LS (Johnson and Faunt 1992). The data were weighted using the standard error of each datum. Donor decay lifetimes were determined for fluorescein attached to both the A arm of the IRES junction and the A arm equivalent of the 24-bp duplex control. Both were fitted best by two lifetimes (τDi and αDi in equation 2), which were then fixed when fitting time-resolved data for the donor-acceptor labeled molecules. The effects of energy transfer on the donor lifetime were fitted by models in which the donor-acceptor distances were described by either a single Gaussian or two Gaussian distributions (equation 9), assuming an R0 of 56 Å (Norman et al. 2000).

|

(9) |

When fitting two Gaussian distributions, it was necessary to fix the relative amplitudes of each distribution (fn in equation 4) to obtain estimates for the centers (c) and half-widths (h). Best fits were obtained for a range of assumed relative amplitudes, and that with the lowest χ2 accepted. Goodness of fit was evaluated by χ2, the distribution of residuals, and by a runs test. Confidence intervals (single-standard deviation) were determined by the Bootstrap method (Efron and Tibshirani 1993).

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Doudna for discussion, and the Cancer Research-UK for financial support.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5130703.

REFERENCES

- Alter, H.J., Purcell, R.H., Shih, J.W., Melpolder, J.C., Houghton, M., Choo, Q.L., and Kuo, G. 1989. Detection of antibody to hepatitis C virus in prospectively followed transfusion recipients with acute and chronic non-A, non-B hepatitis. New Engl. J. Med. 321: 1494–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaucage, S.L. and Caruthers, M.H. 1981. Deoxynucleoside phosphoramidites—a new class of key intermediates for deoxypolynucleotide synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 22: 1859–1862. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.A., Zhang, H., Ping, L.H., and Lemon, S.M. 1992. Secondary structure of the 5′ nontranslated regions of hepatitis C virus and pestivirus genomic RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 20: 5041– 5045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo, Q.L., Kuo, G., Weiner, A.J., Overby, L.R., Bradley, D.W., and Houghton, M. 1989. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 244: 359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, R.M. 1992. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer and nucleic acids. Meth. Enzymol. 211: 353–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, R.M., Murchie, A.I.H., Zechel, A., and Lilley, D.M.J. 1994. The solution structure of the four-way DNA junction at low salt concentration; a fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis. Biophys. J. 66: 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J.P. and Hagerman, P.J. 1987. Gel electrophoretic analysis of the geometry of a DNA four-way junction. J. Mol. Biol. 198: 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mitri, M.S., Poussin, K., Baccarini, P., Pontisso, P., D’Errico, A., Simon, N., Grigioni, W., Alberti, A., Beaugrand, M., Pisi, E., et al. 1995. HCV-associated liver cancer without cirrhosis. Lancet 345: 413–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckett, D.R., Murchie, A.I.H., Diekmann, S., von Kitzing, E., Kemper, B., and Lilley, D.M.J. 1988. The structure of the Holliday junction and its resolution. Cell 55: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckett, D.R., Murchie, A.I.H., and Lilley, D.M.J. 1990. The role of metal ions in the conformation of the four-way junction. EMBO J. 9: 583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. (1995). The global folding of four-way helical junctions in RNA, including that in U1 snRNA. Cell 83: 1027–1036. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Efron, B. and Tibshirani, R.J. 1993. An introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman Hall, New York.

- Eis, P.S. and Millar, D.P. 1993. Conformational distributions of a 4-way DNA junction revealed by time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Biochemistry 32: 13852–13860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg, J.M., Kvaratskhelia, M., White, M.F., and Lilley, D.M.J. 2001. Distortion of DNA junctions imposed by the binding of resolving enzymes: A fluorescence study. J. Mol. Biol. 313: 751–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster, T. 1948. Zwischenmolekulare Energiewanderung und Fluoreszenz. Ann. Phys. 2: 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, G.W. and Lilley, D.M.J. 1985. DNA bending induced by cruciform formation. Nature 313: 154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda, M., Ping, L.H., Rijnbrand, R.C., Amphlett, E., Clarke, B., Rowlands, D.J., and Lemon, S.M. 1996. Structural require−ments for initiation of translation by internal ribosome entry within genome-length hepatitis C virus RNA. Virology 222: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.L. and Faunt, L.M. 1992. Parameter estimation by least-squares methods. Meth. Enzymol. 210: 1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft, J.S., Zhou, K., Grech, A., Jubin, R., and Doudna, J.A. 2002. Crystal structure of an RNA tertiary domain essential to HCV IRES- mediated translation initiation. Nat. Struc. Biol. 9: 370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolupaeva, V.G., Pestova, T.V., and Hellen, C.U. 2000. An enzymatic footprinting analysis of the interaction of 40S ribosomal subunits with the internal ribosomal entry site of hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 74: 6242–6250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz, J.R. 1999. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy, 2nd ed. Plenum Press, New York.

- Liang, T.J., Jeffers, L.J., Reddy, K.R., De Medina, M., Parker, I.T., Cheinquer, H., Idrovo, V., Rabassa, A., and Schiff, E.R. 1993. Viral pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology 18: 1326–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley, D.M.J. 2000. Analysis of the global conformation of branched RNA species by a combined electrophoresis and fluorescence approach. Meth. Enzymol. 317: 368–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley, D.M.J., Clegg, R.M., Diekmann, S., Seeman, N.C., von Kitzing, E., and Hagerman, P. 1995. Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry: A nomenclature of junctions and branchpoints in nucleic acids. Recommendations 1994. Eur. J. Biochem. 230: 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miick, S.M., Fee, R.S., Millar, D.P., and Chazin, W.J. 1997. Crossover isomer bias is the primary sequence-dependent property of immobilized Holliday junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 9080– 9084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.G., Grainger, R.J., Uhrin, D., and Lilley, D.M.J. 2000. The location of Cyanine-3 on double-stranded DNA; importance for fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies. Biochemistry 39: 6317–6324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, J., Shim, P.J., Prasad, G.S., Stout, C.D., and Joyce, G.F. 1999. Crystal structure of an 82 nucleotide RNA-DNA com−plex formed by the 10–23 DNA enzyme, Nat. Struc. Biol. 6: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, J., Shim, P.J., Stout, C.D., and Joyce, G.F. 2000. Alternative conformations of a nucleic acid four-way junction, J. Mol. Biol. 300: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti, R.G., Camma, C., Fiorello, F., Cottone, M., Rapicetta, M., Marino, L., Fiorentino, G., Craxi, A., Ciccaglione, A., Giuseppetti, R., et al. 1992. Hepatitis C virus infection as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. A case-control study. Ann. Intern. Med. 116: 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sizova, D.V., Kolupaeva, V.G., Pestova, T.V., Shatsky, I.N., and Hellen, C.U. 1998. Specific interaction of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 with the 5′ nontranslated regions of hepatitis C virus and classical swine fever virus RNAs. J. Virol. 72: 4775– 4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahn, C.M., Kieft, J.S., Grassucci, R.A., Penczek, P.A., Zhou, K., Doudna, J.A., and Frank, J. 2001. Hepatitis C virus IRES RNA-induced changes in the conformation of the 40s ribosomal subunit. Science 291: 1959–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter, F., Murchie, A.I.H., Duckett, D.R., and Lilley, D.M.J. 1998a. Global structure of four-way RNA junctions studied using fluorescence resonance energy transfer. RNA 4: 719–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter, F., Murchie, A.I.H., and Lilley, D.M.J. 1998b. The folding of the four-way RNA junction of the hairpin ribozyme. Biochemistry 37: 17629–17636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.J., Zhao, Z.-Y., Maxwell, K., Kontogiannis, L., and Lilley, D.M.J. 2001. Importance of specific nucleotides in the folding of the natural form of the hairpin ribozyme. Biochemistry 40: 2291–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.S. and Millar, D.P. 1996. Conformational flexibility of three-way DNA junctions containing unpaired nucleotides. Biochemistry 35: 7959–7967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]