Abstract

Translation of the hepatitis C genome is mediated by internal ribosome entry on the structurally complex 5′ untranslated region of the large viral RNA. Initiation of protein synthesis by this mechanism is independent of the cap-binding factor eIF4E, but activity of the initiator Met-tRNAf-binding factor eIF2 is still required. HCV protein synthesis is thus potentially sensitive to the inhibition of eIF2 activity that can result from the phosphorylation of the latter by the interferon-inducible, double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase PKR. Two virally encoded proteins, NS5A and E2, have been shown to reduce this inhibitory effect of PKR by impairing the activation of the kinase. Here we present evidence for a third viral strategy for PKR inhibition. A region of the viral RNA comprising part of the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) is able to bind to PKR in competition with double-stranded RNA and can prevent autophosphorylation and activation of the kinase in vitro. The HCV IRES itself has no PKR-activating ability. Consistent with these findings, cotransfection experiments employing a bicistronic reporter construct and wild-type PKR indicate that expression of the protein kinase is less inhibitory towards HCV IRES-driven protein synthesis than towards cap-dependent protein synthesis. These data suggest a dual function for the viral IRES, with both a structural role in promoting initiation complex formation and a regulatory role in preventing inhibition of initiation by PKR.

Keywords: Double-stranded RNA, HCV, interferon, IRES function, translational control

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a member of the Flaviviridae family which infects hepatocytes (De Francesco 1999). The virus constitutes a major worldwide public health problem because infection not only causes acute disease but, in the longer term, may also result in conditions such as cirrhosis of the liver and hepatocellular carcinoma (Jenny-Avital 1998; Kiyosawa et al. 1998). The most commonly recommended therapy for HCV infection is interferon (IFN) treatment (usually in combination with ribavirin; Neumann et al. 1998; Shiffman 1999) but the success rate is low (Pawlotsky 2000). This is partially due to the high rate of mutation of the virus, which leads to the generation of a variable mixture of closely related genomes, known as quasispecies, that persist and continuously evolve in infected individuals (Pawlotsky et al. 1998). These mutations can give rise to IFN-resistant phenotypes.

HCV has a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome of ~9450 nt with a single large open reading frame (ORF). The RNA is translated to give a polyprotein of ~3010 amino acids, which is then cleaved by virus-encoded and cellular proteases to yield the viral structural and nonstructural proteins (De Francesco 1999; Rosenberg 2001). An internal ribosome entry site (IRES) has been identified at the 5′ end of the RNA molecule. The HCV IRES (nt 40–372) consists of the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) plus a short length of the HCV coding sequence and is highly conserved between isolates (Soler et al. 2002). In particular, any nucleotide variations found have little effect on the extensive secondary structure of the IRES (Reynolds et al. 1995; Sáiz et al. 1999). The highly structured HCV IRES has several well-defined domains that have been shown to form binding sites for a number of cellular factors, including the La antigen and polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB), as well as polypeptide chain initiation factor eIF3 and 40S ribosomal subunits (Pestova et al. 1998; Sizova et al. 1998; Fukushi et al. 1999, 2001; Ali et al. 2000; Anwar et al. 2000; Spahn et al. 2001; Lytle et al. 2002).

Correct RNA–protein interactions involving the HCV IRES require the conservation of two features: (1) nucleotide sequence and (2) RNA secondary structure. For example, the apical stem-loop region IIIb (Fig. 1) has been shown to bind subunits of protein synthesis initiation factor eIF3, and disruption of the secondary structure of this region results in the loss of both eIF3 binding and IRES activity (Buratti et al. 1998; Odreman-Macchioli et al. 2000). Hairpin IIId has been shown to bind the S9 ribosomal protein, and this binding is also affected by hairpins II and IIIc, suggesting that the RNA has a folded tertiary structure (Kieft et al. 2002). The structure of hairpin IIId is critical for IRES folding (Jubin et al. 2000) and loss of S9 binding leads to undetectable levels of IRES activity (Odreman-Macchioli et al. 2000). These observations suggest that certain conserved stem-loop structures are absolutely required for IRES activity. In contrast, domain I, at the 5′ end, does not play a direct role in the formation of the IRES, but may function to inhibit IRES activity. It is possible that the HCV core protein binds to the IRES and suppresses translation in a dose-dependent manner (Shimoike et al. 1999), although this has been disputed (Wang et al. 2000).

FIGURE 1.

The hepatitis C virus genome and structure of the IRES element. A schematic representation of the organization of the HCV genome is shown at the top with the positions of the IRES and coding regions for the structural proteins (core, E1, and E2) and nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4, NS5A, and NS5B) indicated. The IRES structure is shown below. The regions of secondary structure, the numbering of domains II–IV, and the positions of the pseudoknot and initiation codon are as described in Wang et al. (2000), from which this diagram has been modified. The elements of extensively base-paired and/or tertiary structure may provide a basis for recognition by eIF3, 40S ribosomal subunits, and a variety of cellular proteins, including PKR, as described in the text.

We have been investigating the hypothesis that the extensive secondary structure of the HCV IRES also allows this RNA to be a potential regulator of the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR. The latter is a primary mediator of IFN-induced antiviral and apoptotic responses. Active PKR phosphorylates the α subunit of polypeptide chain initiation factor eIF2 on Ser51, causing inhibition of the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of initiation factor eIF2B and a global shutdown of translation (Clemens 2001a). Because the IFN-induced antiviral response is a cell’s first line of self-defence, for infection to progress, such defence must be overcome by the virus. Many viruses possess strategies for the down-regulation of IFN responses and of PKR activity in particular (Gale and Katze 1998; Korth and Katze 2000), and, in the case of HCV, the viral proteins NS5A and E2 have been shown to function as inhibitors of the protein kinase (Gale et al. 1998; Pawlotsky and Germanidis 1999; Taylor et al. 1999, 2001; Cochrane et al. 2000; Gerotto et al. 2000; Pflugheber et al. 2002).

In the presence of low concentrations of dsRNA, PKR undergoes dimerization and autophosphorylation, which renders it active. However, in the presence of excess dsRNA and certain other structured RNAs, PKR activation is inhibited, probably because of diminished dimerization. Previous studies have established that some viruses (e.g., adenovirus and Epstein-Barr virus) synthesize transcripts possessing extensive secondary structure that are able to interact with PKR in competition with dsRNA activators (Sharp et al. 1993a; Clarke and Mathews 1995; McCormack and Samuel 1995). These viral RNAs prevent the activation of PKR, without themselves having any ability to stimulate PKR function, and thus provide a mechanism by which the kinase is blocked in infected cells. Recent reports have defined the nature of the secondary structure(s) required for interaction with the dsRNA-binding motifs of PKR (Bevilacqua et al. 1998; Spanggord and Beal 2001). The HCV IRES contains several stem-loop elements that are similar to these structures (Fig. 1).

The HCV IRES is unusual in having minimal requirements for the canonical polypeptide chain initiation factors. In particular, assembly of the ribosomal initiation complex on the IRES is independent of any of the eIF4 factors (Kolupaeva et al. 2000; Kieft et al. 2001). These properties would be expected to render HCV translation relatively resistant to cellular stresses or apoptosis-inducing conditions that compromise the availability or integrity of eIF4E, eIF4B, and eIF4G (Bushell et al. 2000, 2001; Clemens et al. 2000). However HCV IRES-driven protein synthesis may potentially still be sensitive to regulation of eIF2 and/or eIF2B activity (Kruger et al. 2000). Previous reports have suggested that the function of several cellular IRESes is resistant to inhibition in stressed or apoptotic cells (Coldwell et al. 2000; Holcik et al. 2000a; Stoneley et al. 2000). In a further aspect of this project, we have therefore investigated whether the early down-regulation of translational activity associated with the induction of apoptosis (Clemens et al. 2000) has a less marked effect on HCV IRES-driven protein synthesis than on cap-dependent translation.

RESULTS

To determine whether the extensive secondary structure of the HCV IRES enables this RNA to bind to PKR a 32P-labeled form of the RNA was transcribed in vitro and incubated with increasing amounts of purified recombinant PKR. Two methods were used to assess the extent of RNA binding to PKR. A filter-binding assay demonstrated that purified PKR was able to cause retention of the labeled RNA on cellulose nitrate filters. Analysis of the binding by phosphorimaging showed that RNA binding was dependent on the amount of PKR present (Fig. 2A). A UV light-induced cross-linking assay, combined with gel analysis of the complexes formed, demonstrated that the RNA binding was specific for PKR and again was concentration dependent (Fig. 2C). The binding was saturable because in either assay association of the 32P-labeled RNA with PKR could be competed out by excess unlabeled HCV IRES (Fig. 2D; data not shown for the filter-binding assay).

FIGURE 2.

Interaction of the HCV IRES with PKR. The HCV IRES sequence was labeled in vitro by transcription in the presence of [α32P]UTP as described in Materials and Methods. (A) The radioactive transcript (105 cpm) was incubated for 15 min at 30°C with the indicated amounts of purified PKR K296R and the extent of complex formation was analysed by filter binding and phosphorimaging as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Incubations were carried out as in Panel A, except that the indicated amounts of unlabeled poly(I).poly(C) were included as competitor for the labeled IRES. (C) Incubations were carried out as in Panel A and the RNA–protein complexes were then subjected to UV cross-linking followed by digestion with RNases A and T1. The labeled protein–RNA complexes were then analyzed by SDS gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging. Molecular mass markers and the position of migration of PKR are indicated. (D) A similar experiment to that described in C was performed except that increasing amounts of unlabeled HCV IRES transcript were included in the incubations, as shown. (E) The radiolabeled HCV IRES was incubated with PKR in the presence of the indicated amounts of unlabeled poly(I).poly(C), followed by UV cross-linking and gel analysis as in C and D. The molar excess levels of poly(I).poly(C) over the HCV IRES were calculated on the basis of an average Mr of 2 × 105 for the double-stranded polymer.

To establish whether the IRES was interacting with the double-stranded RNA-binding domain (dsRBD) of PKR competition experiments with unlabeled poly(I).poly(C) were performed. The synthetic dsRNA was able to compete with the labeled HCV IRES for PKR binding, as assessed by both filter binding (Fig. 2B) and UV cross-linking (Fig. 2E). These results suggest that the HCV IRES binds to the dsRBD of PKR in competition with authentic dsRNA.

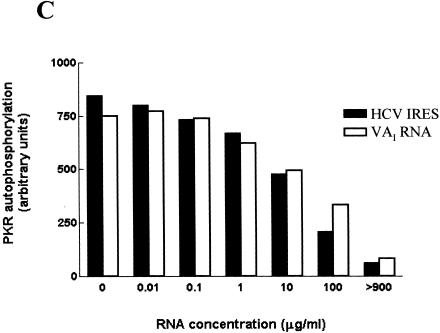

RNA molecules that bind to the dsRNA-binding motifs (dsRBMs) that constitute the dsRBD of PKR can either function as activators or inhibitors of the protein kinase, depending on the RNA concentration and whether they interact with one or both motifs (Spanggord et al. 2002). We therefore investigated whether the HCV IRES possesses either of these activities. Purified wild-type PKR was incubated with a range of concentrations of either poly(I).poly(C) (as a positive control) or the in vitro-transcribed HCV IRES, in the presence of [γ32P]ATP, and the extent of autophosphorylation of the kinase was determined as a measure of the activation of PKR. Figure 3A shows that, as expected, poly(I).poly(C) activated PKR over a concentration range of 0.1 to 10 μg/mL. Higher concentrations of the dsRNA were inhibitory, as previously reported (Clemens et al. 1975; Levin et al. 1980). In contrast, the HCV IRES was unable to activate the kinase when tested at concentrations of up to 10 μg/mL (Fig. 3A). Because the IRES RNA binds to PKR in competition with poly(I).poly(C) (Fig. 2E) but does not itself activate the enzyme, we predicted that the IRES should be able to inhibit the ability of poly(I).poly(C) to activate PKR. Autophosphorylation assays showed that the HCV RNA was indeed able to interfere with the dsRNA-mediated activation of PKR in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). Comparison of the effect of the IRES with that of a well-established RNA inhibitor of the enzyme, adenovirus VAI RNA (Clarke and Mathews 1995), indicated that the two RNAs had almost identical abilities to prevent the activation of PKR by dsRNA (Fig. 3B,C). However the HCV IRES is approximately 2.5 times larger than VAI; thus, on a molar basis, the former is somewhat more potent. These data show that, although PKR is not activated by the secondary structure within the HCV IRES, the viral RNA, like VAI RNA, is able to interact with PKR at high concentrations in a manner that blocks the activation of the kinase by dsRNA. In contrast, another viral IRES, that of encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), activated rather than inhibited PKR in vitro (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of the HCV IRES on the protein kinase activity of PKR. (A) Purified wild-type PKR was incubated with the indicated amounts of poly(I).poly(C) (upper panel) or the HCV IRES transcript (lower panel) in the presence of [γ32P]ATP, as described in Materials and Methods. The extent of activation of the protein kinase, as reflected in the level of autophosphorylation, was determined by SDS gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging. The positions of molecular mass markers and PKR are indicated. (B) PKR was incubated with poly(I).poly(C) (0.1 μg/mL) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the HCV IRES transcript (upper panel) or adenovirus VAI RNA (lower panel) and the extent of autophosphorylation of the protein kinase was determined as in A. (C) The dose-responses for the inhibitory effects of the HCV IRES and VAI RNA on PKR autophosphorylation, as determined by phosphorimaging analysis of the data in B, are depicted graphically.

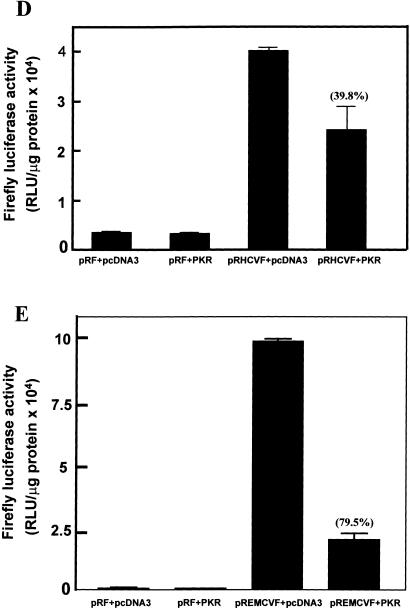

The potential ability of the HCV IRES to inhibit the activation of PKR could be of importance for the maintenance of HCV protein synthesis in infected cells. To test whether the presence of the HCV IRES has a protective effect against PKR-mediated inhibition of protein synthesis in intact cells, we performed a series of cotransfection experiments in which a bicistronic luciferase expression construct, with or without the IRES between the two luciferase cistrons (Fig. 4A; Collier et al. 1998), was introduced into cells in the presence or absence of an expression vector for wild-type PKR (Bommer et al. 2002). In this assay, the expression of Renilla luciferase provides a measure of cap-dependent protein synthesis and the expression of firefly luciferase reflects the extent of IRES-driven translation. To eliminate possible activation of endogenous PKR by the transfection procedure these experiments were performed using murine embryonic fibroblasts from PKR−/− animals (Yang et al. 1995). To control for the possibility that translation from viral IRESes may be generally more resistant than cap-dependent translation to PKR-mediated phosphorylation of eIF2α, we also performed similar experiments using the EMCV IRES in place of the HCV sequence. Figure 4 shows that HCV IRES-driven firefly luciferase activity is indeed much less sensitive than cap-dependent Renilla luciferase activity to inhibition by cotransfected PKR. Whereas expression of the Renilla enzyme is inhibited by PKR by almost 80% in the presence or absence of either viral IRES (Fig. 4B,C), firefly luciferase expression driven by the HCV IRES is inhibited by only about 40% (Fig. 4D). In contrast, EMCV IRES-driven firefly luciferase expression is also inhibited by 80% by cotransfection of PKR (Fig. 4E) and is thus no less sensitive than cap-dependent luciferase activity. [Note that in the absence of either viral IRES almost no firefly enzyme is synthesized (Fig. 4D,E), indicating that internal initiation is entirely dependent on the presence of an IRES sequence.] Thus, in the presence of PKR, the ratio of HCV IRES-dependent to cap-dependent reporter gene expression is more than doubled, whereas PKR has no effect on this ratio in the case of the EMCV IRES (Fig. 4F).

FIGURE 4.

Translation from the HCV IRES is selectively resistant to inhibition by PKR in vivo. Embryonic fibroblasts from PKR−/− mice were transfected with bicistronic constructs containing an upstream Renilla luciferase gene (expressed in a 5′ cap-dependent manner) and a downstream firefly luciferase gene under the control of the HCV IRES (pRHCVF), the EMCV IRES (pREMCVF), or no IRES (pRF). The cells were cotransfected either with an expression vector for wild-type human PKR or with pcDNA3 as a control plasmid. At 21–24 h after transfection, cell extracts were prepared and luciferase activities were determined as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Diagrammatic representation of the bicistronic vectors used. (B, C) Cap-dependent Renilla luciferase activity. (D, E) IRES-dependent firefly luciferase activity. The percent inhibitions by PKR are indicated in parentheses over the appropriate bars. (F) Ratios of IRES-dependent to cap-dependent activity.

These results are consistent with our in vitro evidence that the HCV IRES impairs the activation of PKR. However the presence of the HCV IRES does not relieve inhibition of expression of the upstream Renilla luciferase cistron mediated either by cotransfection of PKR (Fig. 4B) or by activation of the endogenous kinase in PKR+/+ cells (data not shown). The data therefore suggest that the effect of the IRES on the ability of PKR to regulate translation in vivo is exerted in a highly localized manner and that the IRES does not inhibit the activity of PKR in trans.

We also attempted a direct in vivo assay of the effect of the HCV IRES on PKR activation by dsRNA. To do this we tested whether Renilla and/or firefly luciferase activities are less sensitive to poly(I).poly(C)-mediated inhibition when the HCV IRES is also present in the bicistronic luciferase vector (in this case the poly(I).poly(C) was added to cells containing endogenous PKR). However, we observed that poly(I).poly(C) inhibits expression of the enzymes not only in PKR+/+ cells but also in PKR−/− cells (data not shown), indicating that the dsRNA must act by additional PKR-independent mechanism(s) (e.g., activation of 2′ 5′ oligoadenylate synthetases; Justesen et al. 2000). Clearly this makes the data from these experiments impossible to interpret in relation to the specific regulation of PKR by the HCV IRES.

Previous reports have suggested that IRES-driven protein synthesis is more resistant than cap-dependent translation to conditions of cellular stress, at least in the case of several cellular mRNAs. In particular, IRES activity can be maintained during the early stages of apoptosis, when overall protein synthesis is strongly inhibited (Clemens et al. 2000; Holcik et al. 2000a, 2000b). Because HCV infection can induce apoptosis in hepatocytes (Nasir et al. 2000; Kalkeri et al. 2001), it could be of advantage to the virus to prolong the synthesis of its own proteins under these conditions. Moreover, PKR has a marked pro-apoptotic effect (Gil and Esteban 2000; Barber 2001), and it was therefore of interest to determine whether the properties of the HCV IRES might play a role in protecting IRES-driven protein synthesis from inhibition in apoptotic cells. To test this, we used an Huh-7 hepatoma cell line stably transfected with a bicistronic plasmid from which Renilla and firefly luciferases are again translated by cap-dependent and HCV IRES-driven mechanisms, respectively (Honda et al. 2000a; Shimazaki et al. 2002). To induce apoptosis, the Huh-7 cells were treated with TNFα-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL; Srivastava 2001) for 6 h or 22 h. Cell extracts were then prepared and luciferase activities determined. Figure 5 shows that, rather than being protected against TRAIL-induced inhibition, HCV IRES-driven firefly luciferase activity is, in fact, much more strongly inhibited than cap-dependent Renilla luciferase activity under these conditions. These results suggest that, contrary to the apparent selective resistance of cellular IRES activity to inhibition during apoptosis (Holcik et al. 2000a), the HCV IRES may be more sensitive to such inhibition. Similar findings have been reported for the relative responses of HCV IRES-dependent and cap-dependent luciferase activities to the inhibitory effects of increasing cell density, serum starvation, or treatment with interferon in such cell lines (Honda et al. 2000a; Shimazaki et al. 2002), although conflicting data have also been presented (Koev et al. 2002). Thus, although the HCV IRES has PKR-inhibitory properties, these are apparently not sufficient to protect IRES-driven reporter gene expression from inhibition during apoptosis as well as under a variety of other conditions of cell stress.

FIGURE 5.

Reporter gene expression driven by the HCV IRES is sensitive to inhibition during apoptosis. Huh-7 hepatoma cells stably expressing a Renilla luciferase-HCV IRES-firefly luciferase bicistronic construct were incubated with or without TRAIL (0.5 μg/mL) for 6 h or 22 h to induce apoptosis. Cell extracts were prepared and the luciferase activities were determined as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Cap-dependent Renilla luciferase and IRES-dependent firefly luciferase activities. The percent inhibitions resulting from the TRAIL treatment are indicated in parentheses. (B) Ratios of IRES-dependent to cap-dependent activity.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we have presented evidence that the structure at the 5′ end of the HCV genomic RNA that functions as an internal ribosome entry site has an additional role in acting as an inhibitor of the interferon-induced, dsRNA-activated protein kinase PKR. Although interferon has been reported to inhibit HCV replication in hepatocytes in vitro (Castet et al. 2002), it is clear that the virus possesses a number of strategies for evading or limiting the interferon-induced antiviral response (Gale et al. 1999; Taylor et al. 2000; Han and Barton 2002; He and Katze 2002). In particular, PKR is targeted by the virus for inhibition, although other PKR-independent strategies may also be used (Francois et al. 2000; Taylor 2001). The viral proteins NS5A and E2 have been shown to act as inhibitors of PKR function (Gerotto et al. 2000; Taylor et al. 2000; Pflugheber et al. 2002), the former by binding to the kinase and preventing its dimerization (Gale et al. 1998) and the latter by acting as a potential pseudo-substrate for the kinase (Taylor et al. 1999, 2001; Cochrane et al. 2000). However, the roles of these proteins in determining the sensitivity of HCV to IFN treatment are controversial (Duverlie et al. 1998; Odeberg et al. 1998; Noguchi et al. 2001; Sarrazin et al. 2001; Tan and Katze 2001; Schiappa et al. 2002). Here we have identified a third possible mechanism for regulation of PKR by HCV, namely, inhibition of the activation of the enzyme by the highly structured viral IRES.

The HCV IRES has complex and strongly conserved elements of secondary and tertiary structure (Fig. 1; Kieft et al. 1999) that are critical for its function in internal initiation (Odreman-Macchioli et al. 2000, 2001; Collier et al. 2002). Certain aspects of this structure are also likely to be important for the ability of the RNA to interact with the dsRNA-binding domain of PKR. We have not directly measured the affinity of the IRES for PKR but it is likely to be of a similar order of magnitude to that deduced for adenovirus VAI RNA (Sharp et al. 1993a; McCormack and Samuel 1995), as both RNA species show similar concentration dependencies for the inhibition of PKR activation (Fig. 3C). As is the case for VAI (Clarke and Mathews 1995), there is no evidence that the HCV IRES can activate the protein kinase (Fig. 3A). In this respect, HCV can be added to a list of viruses including adenovirus and Epstein-Barr virus (Sharp et al. 1993a; Nanbo et al. 2002) that produce transcripts capable of acting only as inhibitors of PKR. In contrast we have observed that the EMCV IRES is capable of activating PKR in vitro (data not shown). The difference in properties between the two IRESes may explain why HCV-driven but not EMCV-driven luciferase expression is resistant to inhibition by PKR in transiently transfected cells (Fig. 4).

A dual role for a viral IRES in acting as an essential element in the translation of a viral RNA and as an inhibitor of a cellular translational regulatory mechanism is unprecedented. However such a double function is consistent with the high degree of conservation of the secondary structure of the IRES that is observed between HCV isolates. Because both IRES activity in the initiation of translation and the ability to inhibit PKR are features that should favor viral infectivity and resistance to interferon-mediated host defence mechanisms, it is likely that there is strong selection pressure against any mutations that alter the structure of the HCV IRES (Soler et al. 2002). Thus, in contrast to the situation for the viral protein NS5A (and perhaps E2; Taylor et al. 1999; Chayama et al. 2000; Cochrane et al. 2000; Mihm et al. 2000; Sarrazin et al. 2000; Taylor et al. 2000; Lo and Lin 2001; Podevin et al. 2001; Sarrazin et al. 2001; Castelain et al. 2002), differences in the HCV IRES that alter its ability to regulate PKR may not be observed between viral strains because they may also impair the translational activity of the IRES (Laporte et al. 2000). Conservation of secondary structure is likely to be important not only for the binding of PKR but also for recognition of the IRES by cellular protein factors required for the initiation of viral protein synthesis [e.g., polypeptide chain initiation factor eIF3 (Odreman-Macchioli et al. 2000; Collier et al. 2002), the 40S ribosomal subunit (Fukushi et al. 1999, 2001; Kolupaeva et al. 2000; Kieft et al. 2001; Spahn et al. 2001; Lytle et al. 2002), and the La antigen (Ali and Siddiqui 1997)]. Indeed, it is possible that one or more of these ligands competes with PKR for binding to the RNA, but we have not yet tested this. Interestingly, the HCV core protein, which has been reported to have pro-apoptotic activity (Honda et al. 2000b), also binds to the IRES (Tanaka et al. 2000) and may activate PKR (Delhem et al. 2001).

The HCV IRES contains several discrete domains with stem-loop structures that could potentially contribute to the ability of the RNA to interact with PKR and block the activation of the latter by dsRNA (Fig. 1). We have not yet identified the precise binding site for PKR on the HCV IRES, but deletion analyses involving transcription of a series of 3′ truncated forms of the RNA in vitro indicated that forms of the IRES from which domains IIId, IIIe, IV, and the core coding sequence had been deleted were still able to inhibit PKR activation almost as well as the full-length RNA (data not shown). These results suggest that the inhibition of PKR activation does not require sequences or structures on the 3′ side of domain IIId (including the pseudoknot between domains IIIf and IV and the sequence encoding the N-terminal part of the core protein). In contrast these structures are necessary for 40S subunit binding and full HCV IRES function in translation respectively (Hwang et al. 1998; Lytle et al. 2002). Possible candidates for the structures that inhibit PKR are domains II, IIIa, IIIb, and/or IIIc. These regions, especially domain IIIb, contain stem-loops that show several similarities to the minimal structures necessary for PKR binding (Bevilacqua et al. 1998; Spanggord and Beal 2001; Kalliampakou et al. 2002) and it is possible that there is some redundancy of function between them as far as PKR regulation is concerned. It is notable that, although a pseudoknot within the 5′ untranslated region of the mRNA for IFNγ has recently been shown to be necessary for the regulation of PKR by that RNA (Ben-Asouli et al. 2002), the pseudoknot near the 3′ end of the HCV IRES is not required for the inhibition of the kinase. However domain II of the HCV IRES may also contain a tertiary structural element (Lyons et al. 2001). More detailed studies using other deletion and point mutants of the IRES will be required to establish the features necessary for binding to and inhibition of PKR.

We have used cells that have been both transiently and stably transfected with a bicistronic vector containing the HCV IRES to examine the effect of the latter on the response of internally initiated versus cap-dependent protein synthesis to PKR or conditions that regulate the kinase. Our data clearly show that HCV IRES-driven luciferase expression (but not EMCV IRES-driven luciferase expression) is more resistant than cap-dependent expression to inhibition by PKR. While this work was in progress, similar results were reported by Shimazaki et al. (2002) and Rivas-Estilla et al. (2002). In the latter case, PKR was actually able to enhance relative HCV IRES activity by three- to fourfold. These findings are compatible with our observation that PKR activation is blocked by the HCV IRES.

It is, of course, possible that other mechanisms could also explain the resistance of reporter gene expression driven by the IRES to inhibition by PKR in vivo. One possibility, arising from the recent report of a transcriptional promoter within DNA encoding the HCV IRES (Dumas et al. 2003), is that PKR selectively stimulates the activity of this promoter relative to that of the SV40 promoter in the bicistronic vector. Such an effect might negate the consequences of inhibition of firefly luciferase translation by the kinase. Analysis of the sizes and relative levels of the mRNA sequences encoding the Renilla and firefly enzymes will be required to investigate this. It has also been reported that IRES-driven protein synthesis can be maintained under circumstances where eIF2α is phosphorylated (by PKR or other kinases) and indeed that the phosphorylation of eIF2α may be required for this selective IRES activity (Fernandez et al. 2002). In at least one well-documented system, the latter phenomenon also requires the presence of a translatable upstream open reading frame (uORF) within the IRES sequence (Fernandez et al. 2002). However, in the case of the HCV IRES, although three potential uORFs are present upstream of the authentic AUG initiation codon, initiating ribosomes do not appear to scan through them, and the uORFs are not functional (Reynolds et al. 1996; Rijnbrand et al. 1996; Pestova et al. 1998).

Comparison of the effect of PKR on cap-dependent Renilla luciferase expression versus IRES-driven firefly luciferase expression suggests that the effect of the IRES is restricted to localized inhibition of PKR, without any trans-acting effect on the translation of the other cistron. Although at first sight this seems surprising, there are several precedents from other studies for the localized regulation of PKR by RNA ligands in vivo (Akusjarvi et al. 1987; Kaufman and Murtha 1987; Laing et al. 2002), a phenomenon that may be related to the ability of PKR to bind tightly to the ribosome (Raine et al. 1998). Such an effect in the case of HCV would confer an advantage to the virus by ensuring that when PKR is activated as a result of viral RNA replication (Pflugheber et al. 2002), host protein synthesis remains down-regulated but viral protein synthesis escapes this control.

In this study, we have also addressed the issue of whether regulation of PKR by the HCV IRES is an important mechanism in determining the sensitivity of viral protein synthesis to cellular stress and apoptotic conditions. Because PKR is a protein that can both induce apoptosis in its own right and be activated by other conditions that induce cell death (Gil and Esteban 2000; Barber 2001), we considered it possible that the HCV IRES could interfere with the effects of the protein kinase in these circumstances. If that were so it might be expected that protein synthesis initiated from the HCV IRES would be relatively resistant to inhibition during apoptosis. Moreover, because the IRES has reduced requirements for some of the canonical initiation factors such as eIF4G, eIF4B, and eIF4E (Kolupaeva et al. 2000; Kieft et al. 2001) that are either targeted for degradation or functionally inhibited under apoptotic conditions (Clemens et al. 2000; Bushell et al. 2001), IRES activity might be less sensitive to the loss of these factors. In view of these considerations, it is perhaps surprising that HCV IRES function, rather than being selectively resistant to inhibition during apoptosis or other conditions of cell stress, is, in fact, highly sensitive to down-regulation in these circumstances (Fig. 5; Honda et al. 2000a; Shimazaki et al. 2002). However, it is clear that protein synthesis can be inhibited by several mechanisms besides the activation of PKR in cells treated with inducers of apoptosis or exposed to other stress conditions (Clemens et al. 2000; Clemens 2001a, 2001b). Indeed, in the case of interferon treatment, one recent report specifically demonstrates that translation from the HCV IRES is inhibited by a PKR-independent mechanism (Kato et al. 2002). Other noncanonical factors associated with HCV IRES activity, such as the La antigen or PTB (Ali et al. 2000; Anwar et al. 2000), could be targets for regulation by inducers of cell stress and apoptosis (Rutjes et al. 1999; Back et al. 2002). The sensitivity of HCV versus host protein synthesis to inhibition by interferon treatment may vary between cell types (Koev et al. 2002) and further work is clearly required to determine the mechanisms by which HCV IRES-driven protein synthesis is down-regulated in cells subjected to physiological stresses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Radiochemicals were purchased from New England Nuclear or ICN. SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases were from Cambio, and RNAguard was from Amersham Biosciences. FuGENE 6 for transfection was obtained from Roche and the Dual-luciferase assay kit was from Promega.

Plasmids

Plasmids for the in vitro transcription of the HCV IRES (pGHC6) or adenovirus VAI RNA (pVAI) were gifts from Drs. A. Kaminski (Cambridge University, UK) and K. Mellits (University of Nottingham, UK), respectively. The pGHC6 was modified to remove 62 nt from a polylinker region between the transcription start site and the beginning of the HCV sequence, generating plasmid ΔpGHC6 2.2. Plasmids pRF and pREMCVF, containing the SV40 promoter and coding regions for Renilla and firefly luciferases, without or with the IRES sequence of EMCV between the cistrons, respectively, were gifts from Dr. A. Willis (University of Leicester, UK). Plasmid pRHCVF was generated by replacing the EMCV IRES in pREMCVF with the IRES sequence of HCV (nt 40–408). These plasmids were used for transient transfections and subsequent analysis of luciferase expression (Coldwell et al. 2000). Plasmid pCMV-PKR, for in vivo expression of wild-type PKR under the control of the CMV promoter, was a gift from Dr. S. Goodbourn (St. George’s Hospital Medical School, London, UK). Plasmid pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) was used as a control plasmid in experiments involving the transient transfection of these constructs.

In vitro transcription

In vitro transcription reactions were carried out in volumes of 100 μL containing 50 μL 2× transcription buffer (80 mM HEPES-KOH at pH 7.6, 5 mM DTT, 12–16 mM MgCl2, 3 mM of each NTP, 2 mM spermidine), 1 μL RNAguard, 2–5 μg linearized DNA template, and 1 μL SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase (200 units). Transcription was carried out at 37°C for 3 h. The DNA template was removed by adding DNase I and incubating for a further 15 min at 37°C. The transcripts were purified by phenol/chloroform and chloroform extraction and were ethanol precipitated. Radiolabeled transcripts were made using a similar protocol except that the concentration of UTP was reduced to 0.1 mM and 400 μCi/mL [α-32P]UTP (3000 Ci/mmol) was added. The extent of incorporation of 32P into the transcripts was determined by trichloroacetic acid precipitation of the RNA on GF/C filters, followed by liquid scintillation counting.

Purification of PKR

Catalytically active PKR was purified from the ribosomal salt wash of interferon-treated HeLa cells by chromatography on DEAE-cellulose and a mono-S FPLC column as described previously (Sharp et al. 1993a). The appropriate fractions from the mono-S column were analyzed by immunoblotting to locate the PKR and were subsequently characterized for their response to dsRNA activation using an autophosphorylation assay.

The inactive K296R mutant form of PKR (Barber et al. 1992) was purified from baculovirus-infected Sf9 insect cells using DEAE-cellulose and phosphocellulose chromatography as described previously (Sharp et al. 1993b).

RNA–protein-binding assays

Binding of the in vitro-transcribed HCV IRES to PKR was assessed by a modification of the filter-binding assay previously described (Sharp et al. 1993a). This assay is based on the ability of PKR to retain radioactive RNA ligands on cellulose nitrate filters. Briefly, 32P-labeled transcripts were incubated with purified PKR K296R in 25-μL reaction volumes in the presence of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 100 mM KCl, and 0.8 mM Mg acetate for 15 min at 30°C. The complexes were rapidly filtered through cellulose nitrate filters on a microtitre plate and thoroughly washed with the above buffer. The extent of complex formation was quantified by direct phosphorimaging of the relevant wells on the plate. For competition assays, nonradioactive poly(I).poly(C) was included in the incubations at increasing molar excess over the labeled RNA.

UV-induced cross-linking of RNA–protein complexes was also carried out as described previously (Clarke et al. 1991). After incubation as indicated above, bound RNA was cross-linked to protein by irradiation at 254 nm for 5 min at 4°C. The samples were then made 0.5% (w/v) in N-lauroylsarcosine, treated with 20 U RNase T1 and 20 μg RNase A for 1 h at 37°C and analyzed by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging.

Assays of PKR protein kinase activity

PKR autophosphorylation assays were carried out in 10-μL incubations containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MnCl2, 2 μM ATP, 0.1 mM EDTA, 30% (v/v) glycerol, purified wild-type PKR, and 250–500 μCi/mL [γ-32P]ATP. The reactions were incubated for 20 min at 30°C and terminated by the addition of 10 μL of 2× SDS gel loading buffer. The samples were heated for 5 minutes at 95°C, clarified, and subjected to 15% polyacrylamide SDS gel electrophoresis followed by phosphorimaging.

Cell culture

Murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from PKR knockout mice (Yang et al. 1995) were a kind gift from Dr. C. Weissmann (London University, UK). Huh-7 cells stably transfected to express Renilla and firefly luciferases from a bicistronic vector containing the HCV IRES (Honda et al. 2000a) were generously provided by Dr. M. Honda (Kanazawa University, Japan). The cells were grown as monolayers in 78-cm2 flasks at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Life Technologies) and (in the case of the MEFs) 100 μM β-mercaptoethanol. The Huh-7 cells were cultured in the presence of 400 μg/mL G418 (Life Technologies) to maintain selection for the bicistronic vector. Cells were counted using a haemocytometer and subdivided to 1 × 104 cells/cm2 every 2 days.

Transient transfection

Cells were seeded in 10 cm2 wells at 1 × 104 cells/cm2/2 mL of DMEM 1 day before transient transfection of plasmid DNA. The cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of reporter plasmid DNA (pRF, pRHCVF, or pREMCVF), together with 0.5 μg of pcDNA3 or the wild-type PKR-expressing plasmid pCMV-PKR, using FuGENE 6 reagent. The cells were harvested 21–24 h after transfection.

Reporter gene assays

Transfected cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline and harvested into 200 μL of 1× Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega Dual-luciferase assay kit) using a cell scraper. The lysates were immediately frozen at −80°C. Prior to assaying the cell extracts for luciferase activity, the samples were thawed, vortexed, and clarified by centrifugation in a bench-top centrifuge for 2 min. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Bradford 1976).

The activities of Renilla and firefly luciferases were measured by adding 5 μL of cell extract to 25 μL of assay reagent. Luminescence due to the activity of the firefly luciferase was measured over 10 s using a Sirius luminometer. Twenty-five microliters of Stop-and-Glo buffer (Promega) were then added and the activity of the Renilla luciferase was determined in the same manner. All measurements were performed in triplicate and were within the linear ranges of the assays. The data are normalized to the protein concentrations of the cell extracts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Mark Coldwell, Masao Honda, Ann Kaminski, Athanasios Tzortzopoulos, Charles Weissmann, and Anne Willis for cell lines, reagents, and advice and Dr. Simon Morley for assistance in the FPLC purification of PKR. This research was supported by a Ph.D. studentship awarded to J.V. by the Medical Research Council and Roche Discovery, and by grants from the Leukaemia Research Fund and the Wellcome Trust.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5330503.

REFERENCES

- Akusjarvi, G., Svensson, C., and Nygard, O. 1987. A mechanism by which adenovirus virus-associated RNA 1 controls translation in a transient expression assay. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7: 549–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N. and Siddiqui, A. 1997. The La antigen binds 5′ noncoding region of the hepatitis C virus RNA in the context of the initiator AUG codon and stimulates internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 2249–2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N., Pruijn, G.J.M., Kenan, D.J., Keene, J.D., and Siddiqui, A. 2000. Human La antigen is required for the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 27531–27540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, A., Ali, N., Tanveer, R., and Siddiqui, A. 2000. Demonstration of functional requirement of polypyrimidine tract- binding protein by SELEX RNA during hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 34231– 34235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back, S.H., Shin, S.J., and Jang, S.K. 2002. Polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins are cleaved by caspase-3 during apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 27200–27209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber, G.N. 2001. Host defense, viruses and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 8: 113–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber, G.N., Tomita, J., Garfinkel, M.S., Meurs, E., Hovanessian, A., and Katze, M.G. 1992. Detection of protein kinase homologues and viral RNA-binding domains utilizing polyclonal antiserum prepared against a baculovirus-expressed ds RNA-activated 68,000-Da protein kinase. Virology 191: 670–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Asouli, Y., Banai, Y., Pel-Or, Y., Shir, A., and Kaempfer, R. 2002. Human interferon-γ mRNA autoregulates its translation through a pseudoknot that activates the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR. Cell 108: 221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, P.C., George, C.X., Samuel, C.E., and Cech, T.R. 1998. Binding of the protein kinase PKR to RNAs with secondary structure defects: Role of the tandem A-G mismatch and noncontiguous helixes. Biochemistry 37: 6303–6316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommer, U.A., Borovjagin, A.V., Greagg, M.A., Jeffrey, I.W., Russell, P., Laing, K.G., Lee, M., and Clemens, M.J. 2002. The mRNA of the translationally controlled tumor protein P23/TCTP is a highly structured RNA, which activates the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. RNA 8: 478–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analyt. Biochem. 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratti, E., Tisminetzky, S., Zotti, M., and Baralle, F.E. 1998. Functional analysis of the interaction between HCV 5′UTR and putative subunits of eukaryotic translation initiation factor elF3. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 3179–3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushell, M., Wood, W., Clemens, M.J., and Morley, S.J. 2000. Changes in integrity and association of eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factors during apoptosis. Eur. J. Biochem. 267: 1083–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushell, M., Wood, W., Carpenter, G., Pain, V.M., Morley, S.J., and Clemens, M.J. 2001. Disruption of the interaction of mammalian protein synthesis eukaryotic initiation factor 4B with the poly(A)-binding protein by caspase- and viral protease-mediated cleavages. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 23922–23928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelain, S., Khorsi, H., Roussel, J., Francois, C., Jaillon, O., Capron, D., Penin, F., Wychowski, C., Meurs, E., and Duverlie, G. 2002. Variability of the nonstructural 5A protein of hepatitis C virus type 3a isolates and relation to interferon sensitivity. J. Infect. Diseases 185: 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castet, V., Fournier, C., Soulier, A., Brillet, R., Coste, J., Larrey, D., Dhumeaux, D., Maurel, P., and Pawlotsky, J.M. 2002. α interferon inhibits hepatitis C virus replication in primary human hepatocytes infected in vitro. J. Virol. 76: 8189–8199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chayama, K., Suzuki, F., Tsubota, A., Kobayashi, M., Arase, Y., Saitoh, S., Suzuki, Y., Murashima, N., Ikeda, K., Takahashi, N., et al. 2000. Association of amino acid sequence in the PKR-eIF2 phosphorylation homology domain and response to interferon therapy. Hepatology 32: 1138–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, P.A. and Mathews, M.B. 1995. Interaction between the double-stranded RNA binding motif and RNA: Definition of the binding site for the interferon-induced protein kinase DAI (PKR) on adenovirus VA RNA. RNA 1: 7–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, P.A., Schwemmle, M., Schickinger, J., Hilse, K., and Clemens, M.J. 1991. Binding of Epstein-Barr virus small RNA EBER-1 to the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase DAI. Nucleic Acids Res. 19: 243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens, M.J. 2001a. Initiation factor eIF2 α phosphorylation in stress responses and apoptosis. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 27: 57–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2001b. Translational regulation in cell stress and apoptosis. Roles of the eIF4E binding proteins. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 5: 221–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens, M.J., Safer, B., Merrick, W.C., Anderson, W.F., and London, I.M. 1975. Inhibition of protein synthesis in rabbit reticulocyte lysates by double-stranded RNA and oxidized glutathione: Indirect mode of action on polypeptide chain initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 72: 1286–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens, M.J., Bushell, M., Jeffrey, I.W., Pain, V.M., and Morley, S.J. 2000. Translation initiation factor modifications and the regulation of protein synthesis in apoptotic cells. Cell Death Differ. 7: 603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, A., Orr, A., Shaw, M.L., Mills, P.R., and McCruden, E.A.B. 2000. The amino acid sequence of the PKR-eIF2α phosphorylation homology domain of hepatitis C virus envelope 2 protein and response to interferon-α. J. Infect. Diseases 182: 1515–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell, M.J., Mitchell, S.A., Stoneley, M., MacFarlane, M., and Willis, A.E. 2000. Initiation of Apaf-1 translation by internal ribosome entry. Oncogene 19: 899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier, A.J., Tang, S.X., and Elliott, R.M. 1998. Translation efficiencies of the 5′ untranslated region from representatives of the six major genotypes of hepatitis C virus using a novel bicistronic reporter assay system. J. Gen. Virol. 79: 2359–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier, A.J., Gallego, J., Klinck, R., Cole, P.T., Harris, S.J., Harrison, G.P., Aboul-Ela, F., Varani, G., and Walker, S. 2002. A conserved RNA structure within the HCV IRES eIF3-binding site. Nature Struct. Biol. 9: 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco, R. 1999. Molecular virology of the hepatitis C virus. J. Hepatol. 31, Suppl. 1: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhem, N., Sabile, A., Gajardo, R., Podevin, P., Abadie, A., Blaton, M.A., Kremsdorf, D., Beretta, L., and Brechot, C. 2001. Activation of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR by Hepatocellular carcinoma derived-Hepatitis C virus core protein. Oncogene 20: 5836–5845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, E., Staedel, C., Colombat, M., Reigadas, S., Chabas, S., Astier-Gin, T., Cahour, A., Litvak, S. and Ventura, M. 2003. A promoter activity is present in the DNA sequence corresponding to the hepatitis C virus 5′ UTR. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 1275–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duverlie, G., Khorsi, H., Castelain, S., Jaillon, O., Izopet, J., Lunel, F., Eb, F., Penin, F., and Wychowski, C. 1998. Sequence analysis of the NS5A protein of European hepatitis C virus 1b isolates and relation to interferon sensitivity. J. Gen. Virol. 79: 1373–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, J., Yaman, I., Merrick, W.C., Koromilas, A., Wek, R.C., Sood, R., Hensold, J., and Hatzoglou, M. 2002. Regulation of internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation by eukaryotic initiation factor-2alpha phosphorylation and translation of a small upstream open reading frame. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 2050–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois, C., Duverlie, G., Rebouillat, D., Khorsi, H., Castelain, S., Blum, H.E., Gatignol, A., Wychowksi, C., Moradpour, D., and Meurs, E.F. 2000. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins interferes with the antiviral action of interferon independently of PKR-mediated control of protein synthesis. J. Virol. 74: 5587–5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushi, S., Okada, M., Kageyama, T., Hoshino, F.B., and Katayama, K. 1999. Specific interaction of a 25-kilodalton cellular protein, a 40S ribosomal subunit protein, with the internal ribosome entry site of hepatitis C virus genome. Virus Genes 19: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushi, S., Okada, M., Stahl, J., Kageyama, T., Hoshino, F.B., and Katayama, K. 2001. Ribosomal protein S5 interacts with the internal ribosomal entry site of hepatitis C virus. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 20824–20826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale Jr., M., and Katze, M.G. 1998. Molecular mechanisms of interferon resistance mediated by viral-directed inhibition of PKR, the interferon-induced protein kinase. Pharmacol. Ther. 78: 29–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale Jr., M., Blakely, C.M., Kwieciszewski, B., Tan, S.L., Dossett, M., Tang, N.M., Korth, M.J., Polyak, S.J., Gretch, D.R., and Katze, M.G. 1998. Control of PKR protein kinase by hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein: Molecular mechanisms of kinase regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 5208–5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale Jr., M., Kwieciszewski, B., Dossett, M., Nakao, H., and Katze, M.G. 1999. Antiapoptotic and oncogenic potentials of hepatitis C virus are linked to interferon resistance by viral repression of the PKR protein kinase. J. Virol. 73: 6506–6516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerotto, M., Dal Pero, F., Pontisso, P., Noventa, F., Gatta, A., and Alberti, A. 2000. Two PKR inhibitor HCV proteins correlate with early but not sustained response to interferon. Gastroenterology 119: 1649–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil, J. and Esteban, M. 2000. Induction of apoptosis by the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR): Mechanism of action. Apoptosis 5: 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.Q. and Barton, D.J. 2002. Activation and evasion of the antiviral 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase/ribonuclease L pathway by hepatitis C virus mRNA. RNA 8: 512–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. and Katze, M.G. 2002. To interfere and to anti-interfere: The interplay between hepatitis C virus and interferon. Viral Immunol. 15: 95–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik, M., Sonenberg, N., and Korneluk, R.G. 2000a. Internal ribosome initiation of translation and the control of cell death. Trends Genet. 16: 469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik, M., Yeh, C., Korneluk, R.G., and Chow, T. 2000b. Translational upregulation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) increases resistance to radiation induced cell death. Oncogene 19: 4174–4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda, M., Kaneko, S., Matsushita, E., Kobayashi, K., Abell, G.A., and Lemon, S.M. 2000a. Cell cycle regulation of hepatitis C virus internal ribosomal entry site-directed translation. Gastroenterology 118: 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda, M., Kaneko, S., Shimazaki, T., Matsushita, E., Kobayashi, K., Ping, L.H., Zhang, H.C., and Lemon, S.M. 2000b. Hepatitis C virus core protein induces apoptosis and impairs cell-cycle regulation in stably transformed Chinese hamster ovary cells. Hepatology 31: 1351–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, L.H., Hsieh, C.L., Yen, A., Chung, Y.L., and Chen, D.S. 1998. Involvement of the 5′ proximal coding sequences of hepatitis C virus with internal initiation of viral translation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 252: 455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny-Avital, E.R. 1998. Hepatitis C. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 11: 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubin, R., Vantuno, N.E., Kieft, J.S., Murray, M.G., Doudna, J.A., Lau, J.Y.N., and Baroudy, B.M. 2000. Hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site (IRES) stem loop IIId contains a phylogenetically conserved GGG triplet essential for translation and IRES folding. J. Virol. 74: 10430–10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justesen, J., Hartmann, R., and Kjeldgaard, N.O. 2000. Gene structure and function of the 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase family. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57: 1593–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkeri, G., Khalap, N., Akhter, S., Garry, R.F., Fermin, C.D., and Dash, S. 2001. Hepatitis C viral proteins affect cell viability and membrane permeability. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 71: 194–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalliampakou, K.I., Psaridi-Linardaki, L., and Mavromara, P. 2002. Mutational analysis of the apical region of domain II of the HCV IRES. FEBS Lett. 511: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato, J., Kato, N., Moriyama, M., Goto, T., Taniguchi, H., Shiratori, Y., and Omata, M. 2002. Interferons specifically suppress the translation from the internal ribosome entry site of hepatitis C virus through a double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-independent pathway. J. Infect. Diseases 186: 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, R.J. and Murtha, P. 1987. Translational control mediated by eukaryotic initiation factor-2 is restricted to specific mRNAs in transfected cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7: 1568–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft, J.S., Zhou, K.H., Jubin, R., Murray, M.G., Lau, J.Y.N., and Doudna, J.A. 1999. The hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site adopts an ion-dependent tertiary fold. J. Mol. Biol. 292: 513–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft, J.S., Zhou, K.H., Jubin, R., and Doudna, J.A. 2001. Mechanism of ribosome recruitment by hepatitis C IRES RNA. RNA 7: 194–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft, J.S., Zhou, K.H., Grech, A., Jubin, R., and Doudna, J.A. 2002. Crystal structure of an RNA tertiary domain essential to HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation. Nature Struct. Biol. 9: 370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyosawa, K., Tanaka, E., and Sodeyama, T. 1998. Hepatitis C virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr. Stud. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 62: 161–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koev, G., Duncan, R.F., and Lai, M.M.C. 2002. Hepatitis C virus IRES-dependent translation is insensitive to an eIF2α-independent mechanism of inhibition by interferon in hepatocyte cell lines. Virology 297: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolupaeva, V.G., Pestova, T.V., and Hellen, C.U.T. 2000. An enzymatic footprinting analysis of the interaction of 40S ribosomal subunits with the internal ribosomal entry site of hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 74: 6242–6250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth, M.J. and Katze, M.G. 2000. Evading the interferon response: Hepatitis C virus and the interferon-induced protein kinase, PKR. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 242: 197–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, M., Beger, C., Li, Q.X., Welch, P.J., Tritz, R., Leavitt, M., Barber, J.R., and Wong-Staal, F. 2000. Identification of eIF2Bγ and eIF2γ as cofactors of hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation using a functional genomics approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 8566–8571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing, K.G., Elia, A., Jeffrey, I., Matys, V., Tilleray, V.J., Souberbielle, B., and Clemens, M.J. 2002. In vivo effects of the Epstein-Barr virus small RNA EBER-1 on protein synthesis and cell growth regulation. Virology 297: 253–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, J., Malet, I., Andrieu, T., Thibault, V., Toulme, J.J., Wychowski, C., Pawlotsky, J.M., Huraux, J.M., Agut, H., and Cahour, A. 2000. Comparative analysis of translation efficiencies of hepatitis C virus 5′ untranslated regions among intraindividual quasispecies present in chronic infection: Opposite behaviors depending on cell type. J. Virol. 74: 10827–10833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, D.H., Petryshyn, R., and London, I.M. 1980. Characterization of a double-stranded RNA-activated kinase that phosphorylates α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF-2α) in reticulocyte lysates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 77: 832–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo, S.Y. and Lin, H.H. 2001. Variations within hepatitis C virus E2 protein and response to interferon treatment. Virus Res. 75: 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, A.J., Lytle, J.R., Gomez, J., and Robertson, H.D. 2001. Hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site RNA contains a tertiary structural element in a functional domain of stem-loop II. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 2535–2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, J.R., Wu, L., and Robertson, H.D. 2002. Domains on the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site for 40s subunit binding. RNA 8: 1045–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, S.J. and Samuel, C.E. 1995. Mechanism of interferon action: RNA-binding activity of full-length and R-domain forms of the RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR—Determination of KD values for VAl and TAR RNAs. Virology 206: 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihm, S., Monazahian, M., Grethe, S., Meier, V., Thomssen, R., and Ramadori, G. 2000. Lack of clinical evidence for involvement of hepatitis C virus interferon-α sensitivity-determining region variability in RNA-dependent protein kinase-mediated cellular antiviral responses. J. Med. Virol. 61: 29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanbo, A., Inoue, K., Adachi-Takasawa, K., and Takada, K. 2002. Epstein-Barr virus RNA confers resistance to interferon- α-induced apoptosis in Burkitt’s lymphoma. EMBO J. 21: 954–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, A., Arora, H.S., and Kaiser, H.E. 2000. Apoptosis and pathogenesis of viral hepatitis C—An update. In vivo 14: 297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, A.U., Lam, N.P., Dahari, H., Gretch, D.R., Wiley, T.E., Layden, T.J., and Perelson, A.S. 1998. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-α therapy. Science 282: 103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, T., Satoh, S., Noshi, T., Hatada, E., Fukuda, R., Kawai, A., Ikeda, S., Hijikata, M., and Shimotohno, K. 2001. Effects of mutation in hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A on interferon resistance mediated by inhibition of PKR kinase activity in mammalian cells. Microbiol. Immunol. 45: 829–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odeberg, J., Yun, Z.B., Sönnerborg, A., Weiland, O., and Lundeberg, J. 1998. Variation in the hepatitis C virus NS5a region in relation to hypervariable region 1 heterogeneity during interferon treatment. J. Med. Virol. 56: 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odreman-Macchioli, F.E., Tisminetzky, S.G., Zotti, M., Baralle, F.E., and Buratti, E. 2000. Influence of correct secondary and tertiary RNA folding on the binding of cellular factors to the HCV IRES. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 875–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odreman-Macchioli, F., Baralle, F.E., and Buratti, E. 2001. Mutational analysis of the different bulge regions of hepatitis C virus domain II and their influence on internal ribosome entry site translational ability. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 41648–41655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlotsky, J.M. 2000. Hepatitis C virus resistance to antiviral therapy. Hepatology 32: 889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlotsky, J.M. and Germanidis, G. 1999. The non-structural 5A protein of hepatitis C virus. J. Viral Hepat. 6: 343–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlotsky, J.M., Pellerin, M., Bouvier, M., Roudot-Thoraval, F., Germanidis, G., Bastie, A., Darthuy, F., Rémiré, J., Soussy, C.J., and Dhumeaux, D. 1998. Genetic complexity of the hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) of hepatitis C virus (HCV): Influence on the characteristics of the infection and responses to interferon alfa therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Med. Virol. 54: 256–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova, T.V., Shatsky, I.N., Fletcher, S.P., Jackson, R.T., and Hellen, C.U.T. 1998. A prokaryotic-like mode of cytoplasmic eukaryotic ribosome binding to the initiation codon during internal translation initiation of hepatitis C and classical swine fever virus RNAs. Genes & Dev. 12: 67–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugheber, J., Fredericksen, B., Sumpter, R., Wang, C., Ware, F., Sodora, D.L., and Gale, M. 2002. Regulation of PKR and IRF-1 during hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 4650–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podevin, P., Sabile, A., Gajardo, R., Delhem, N., Abadie, A., Lozach, P.Y., Beretta, L., and Brechot, C. 2001. Expression of hepatitis C virus NS5A natural mutants in a hepatocytic cell line inhibits the antiviral effect of interferon in a PKR-independent manner. Hepatology 33: 1503–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine, D.A., Jeffrey, I.W., and Clemens, M.J. 1998. Inhibition of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR by mammalian ribosomes. FEBS Lett. 436: 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J.E., Kaminski, A., Kettinen, H.J., Grace, K., Clarke, B.E., Carroll, A.R., Rowlands, D.J., and Jackson, R.J. 1995. Unique features of internal initiation of hepatitis C virus RNA translation. EMBO J. 14: 6010–6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J.E., Kaminski, A., Carroll, A.R., Clarke, B.E., Rowlands, D.J., and Jackson, R.J. 1996. Internal initiation of translation of hepatitis C virus RNA: The ribosome entry site is at the authentic initiation codon. RNA 2: 867–878. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijnbrand, R.C., Abbink, T.E., Haasnoot, P.C., Spaan, W.J., and Bredenbeek, P.J. 1996. The influence of AUG codons in the hepatitis C virus 5′ nontranslated region on translation and mapping of the translation initiation window. Virology 226: 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Estilla, A.M., Svitkin, Y., Lastra, M.L., Hatzoglou, M., Sherker, A., and Koromilas, A.E. 2002. PKR-dependent mechanisms of gene expression from a subgenomic hepatitis C virus clone. J. Virol. 76: 10637–10653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, S. 2001. Recent advances in the molecular biology of Hepatitis C virus. J. Mol. Biol. 313: 451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutjes, S.A., Utz, P.J., van der Heijden, A., Broekhuis, C., van Venrooij, W.J., and Pruijn, G.J.M. 1999. The La (SS-B) autoantigen, a key protein in RNA biogenesis, is dephosphorylated and cleaved early during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 6: 976–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin, C., Berg, T., Lee, J.H., Ruster, B., Kronenberger, B., Roth, W.K., and Zeuzem, S. 2000. Mutations in the protein kinase-binding domain of the NS5A protein in patients infected with hepatitis C virus type 1a are associated with treatment response. J. Infect. Diseases 181: 432–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin, C., Bruckner, M., Herrmann, E., Rüster, B., Bruch, K., Roth, W.K., and Zeuzem, S. 2001. Quasispecies heterogeneity of the carboxy-terminal part of the E2 gene including the PePHD and sensitivity of hepatitis C virus 1b isolates to antiviral therapy. Virology 289: 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáiz, J.C., De Quinto, S.L., Ibarrola, N., López-Labrador, F.X., Sánchez-Tapias, J.M., Rodés, J., and Martínez-Salas, E. 1999. Internal initiation of translation efficiency in different hepatitis C genotypes isolated from interferon treated patients. Arch. Virol. 144: 215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiappa, D.A., Mittal, C., Brown, J.A., and Mika, B.P. 2002. Relationship of hepatitis C genotype 1 NS5A sequence mutations to early phase viral kinetics and interferon effectiveness. J. Infect. Diseases 185: 868–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman, M.L. 1999. Use of high-dose interferon in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Semin. Liver Dis. 19, Suppl. 1: 25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki, T., Honda, M., Kaneko, S., and Kobayashi, K. 2002. Inhibition of internal ribosomal entry site-directed translation of HCV by recombinant IFN-α correlates with a reduced La protein. Hepatology 35: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoike, T., Mimori, S., Tani, H., Matsuura, Y., and Miyamura, T. 1999. Interaction of hepatitis C virus core protein with viral sense RNA and suppression of its translation. J. Virol. 73: 9718–9725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sizova, D.V., Kolupaeva, V.G., Pestova, T.V., Shatsky, I.N., and Hellen, C.U.T. 1998. Specific interaction of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 with the 5′ nontranslated regions of hepatitis C virus and classical swine fever virus RNAs. J. Virol. 72: 4775–4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler, M., Pellerin, M., Malnou, C.E., Dhumeaux, D., Kean, K.M., and Pawlotsky, J.M. 2002. Quasispecies heterogeneity and constraints on the evolution of the 5′ noncoding region of hepatitis C virus (HCV): Relationship with HCV resistance to interferon-α therapy. Virology 298: 160–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahn, C.M.T., Kieft, J.S., Grassucci, R.A., Penczek, P.A., Zhou, K.H., Doudna, J.A., and Frank, J. 2001. Hepatitis C virus IRES RNA-induced changes in the conformation of the 40S ribosomal subunit. Science 291: 1959–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanggord, R.J. and Beal, P.A. 2001. Selective binding by the RNA binding domain of PKR revealed by affinity cleavage. Biochemistry 40: 4272–4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanggord, R.J., Vuyisich, M., and Beal, P.A. 2002. Identification of binding sites for both dsRBMs of PKR on kinase-activating and kinase-inhibiting RNA ligands. Biochemistry 41: 4511–4520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, R.K. 2001. TRAIL/Apo-2L: Mechanisms and clinical applications in cancer. Neoplasia 3: 535–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneley, M., Chappell, S.A., Jopling, C.L., Dickens, M., MacFarlane, M., and Willis, A.E. 2000. c-Myc protein synthesis is initiated from the internal ribosome entry segment during apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 1162–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.L. and Katze, M.G. 2001. How hepatitis C virus counteracts the interferon response: The jury is still out on NS5A. Virology 284: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y., Shimoike, T., Ishii, K., Suzuki, R., Suzuki, T., Ushijima, H., Matsuura, Y., and Miyamura, T. 2000. Selective binding of hepatitis C virus core protein to synthetic oligonucleotides corresponding to the 5′ untranslated region of the viral genome. Virology 270: 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R. 2001. Hepatitis C virus and interferon resistance: it’s more than just PKR. Hepatology 33: 1547–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R., Shi, S.T., Romano, P.R., Barber, G.N., and Lai, M.M.C. 1999. Inhibition of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR by HCV E2 protein. Science 285: 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R., Shi, S.T., and Lai, M.M.C. 2000. Hepatitis C virus and interferon resistance. Microbe. Infect. 2: 1743–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R., Tian, B., Romano, P.R., Hinnebusch, A.G., Lai, M.M.C., and Mathews, M.B. 2001. Hepatitis C virus envelope protein E2 does not inhibit PKR by simple competition with autophosphorylation sites in the RNA-binding domain. J. Virol. 75: 1265–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.H., Rijnbrand, R.C.A., and Lemon, S.M. 2000. Core protein-coding sequence, but not core protein, modulates the efficiency of cap-independent translation directed by the internal ribosome entry site of hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 74: 11347–11358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.-L., Reis, L.F.L., Pavlovic, J., Aguzzi, A., Schafer, R., Kumar, A., Williams, B.R.G., Aguet, M., and Weissmann, C. 1995. Deficient signalling in mice devoid of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR. EMBO J. 14: 6095–6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]