Abstract

A better understanding of aptamer function in bacteria would help to establish simple model systems for screening RNA–protein interactions within an intracellular context. Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I mutants (Pol Its) fail to grow at 37°C unless an exogenous DNA polymerase such as HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) is expressed within the cell. Here, we show that four RNA aptamers that inhibit HIV-1 RT in vitro block complementation by HIV-1 RT when expressed in vivo. No other essential functions are impaired by aptamer expression at either temperature. Intracellular aptamer RNA concentrations from induced cultures were measured to range from 76 to 180 nM, which is comparable with exogenously expressed HIV-1 RT levels in these cells. RT polymerase activity was reduced to background levels in cell-free extracts prepared from cultures expressing both HIV-1 RT and the 70.28 aptamer, compared with extracts from cultures expressing HIV-1 RT alone. Intracellularly expressed RNA aptamers can thus be used to generate conditional null mutants in bacteria by titrating an essential protein.

Keywords: SELEX, aptamer, RNA–protein interactions, bioassay, HIV-1 reverse transcriptase

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of infection by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) generally includes small molecule inhibitors of the viral reverse transcriptase (RT). However, drug-resistant forms of RT are selected by prolonged treatment, prompting widespread efforts to generate new anti-RT drugs. Both RNA and ssDNA aptamers that bind HIV-1 RT with high affinity have been identified through the SELEX protocol (Tuerk et al. 1992; Schneider et al. 1995; Burke et al. 1996; Andreola et al. 2001). When any of several different RNA aptamers was expressed in human T293 cells, the susceptibility of these cells to HIV infection was reduced, and the infectivity of viruses produced by infected T293 cells is reduced 90%–99% compared with cells not expressing aptamers (Joshi and Prasad 2002). Human T-lymphoid cell lines expressing the 33-nt TPK1.1 aptamer also demonstrated intracellular inhibition of RT and protection against HIV-1 infection (Chaloin et al. 2002).

The aptamer-RT interaction represents one of more than a dozen examples wherein an aptamer retains its target-binding function when expressed in eukaryotic cells and exerts observable influence on the biology of those cells (Burke and Nickens 2002). Less is known about aptamer function in bacterial cells. Whereas translational regulation by small molecules has been observed both in engineered (Werstuck and Green 1998) and natural systems (Nahvi et al. 2002; Winkler et al. 2002a,b), enzyme antagonism by aptamers within bacteria has not been reported. Bacteria offer several advantages for studying RNA–protein interactions, including ease of genetic manipulation and lower cost of maintaining cell lines. At the same time, a number of characteristics of the bacterial microenvironment could affect aptamer function, including the short average lifetime of bacterial mRNA transcripts, counterion concentrations, and macromolecular constituents. A better understanding of aptamer function in bacteria would help to establish the extent to which such model systems can be used in rapid screens of intracellular aptamer–protein interactions.

This study utilizes Escherichia coli strain BK148, which carries a temperature-sensitive DNA polymerase I (polA12) that allows normal growth at 30°C but restricts the formation of isolated colonies at 37°C (Witkin and Roegner-Maniscalco 1992). Expression of an exogenous DNA polymerase such as HIV-1 RT (Kim and Loeb 1995; Kim et al. 1996) or rat DNA polymerase β (Sweasy and Loeb 1992) restores replication and normal growth at 37°C. Small molecule nucleoside prodrug inhibitors of HIV-1 RT re-established temperature sensitivity of the Pol Its/HIV-1 RT strain at 37°C (Kim and Loeb 1995; Kim et al. 1996), demonstrating that the DNA polymerase activity of the RT is responsible for growth at the restrictive temperature. We demonstrate here that RT complementation of the Pol I defect is blocked by inhibitory RNA aptamers, creating a conditional null phenotype suitable for evaluating libraries of HIV-1 RT mutants for aptamer-resistant variants.

RESULTS

Complementation of Pol Its by HIV-1 RT

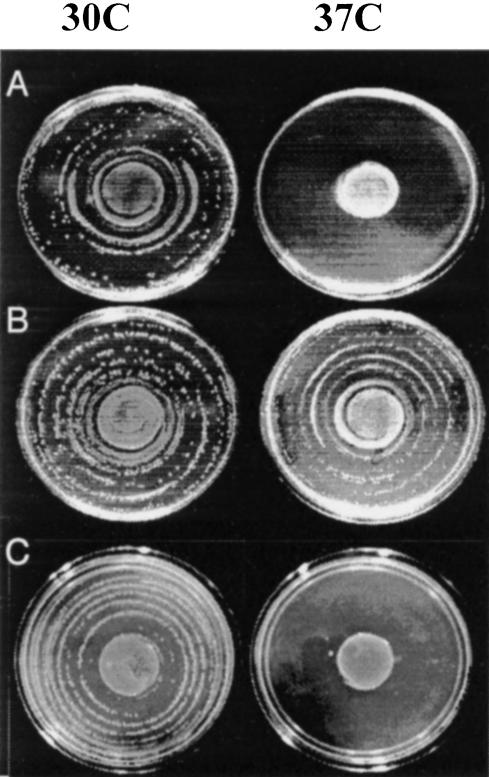

Plasmid pRT5 was constructed to direct low-level expression of HIV-1 RT (Fig. 1A ▶). When duplicate concentric spiral streak plates of E. coli strain BK148 (Pol Its) were incubated at 30°C and 37°C, cells expressing HIV-1 RT from plasmid pRT5 formed isolated colonies out to the edge of the spiral at both temperatures, whereas cells from control cultures with plasmid pHSG576 formed isolated colonies only at the permissive temperature (Fig. 2A,B ▶). Growth at the center of spiral streak plates is observed irrespective of temperature or plasmid. These results are consistent with previously observed density-dependent growth (Kim and Loeb 1995; Kim et al. 1996; Kim 1997). End-point serial dilutions of freshly saturated cultures resulted in resaturation at all dilutions assayed when HIV-1 RT was expressed in the strain. In contrast, at least three to four orders of magnitude higher initial density of BK148 was required for growth in culture when the strain did not express HIV-1 RT (Table 1 ▶).

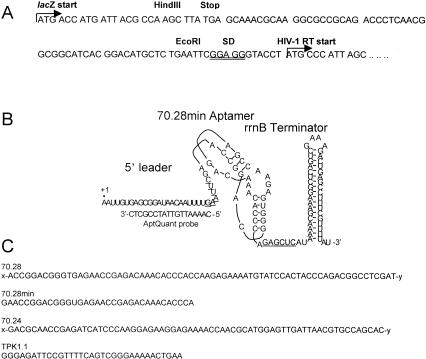

FIGURE 1.

(A) Sequences in plasmid pRT5 controlling translation of HIV-1 RT expression. Restriction sites used in cloning are indicated. Translational start sites are indicated with arrows; Shine-Dalgarno sequence for translation of HIV-1 RT is double-underlined. (B) Aptamer RNA expressed from construct p70.28min. Nucleotides corresponding to EcoRI and SacI sites used in cloning this and other aptamers are underlined. AptQuant oligonucleotide used as a probe for aptamer detection is shown adjacent to its hybridization target, which is present in all aptamer expression constructs. (C) Sequences of aptamer inserts used in this study. For aptamers 70.28 and 70.24, the notations x and y represent the following sequences: (x) 5′-gggaaaagcgaaucauacacaaga-3′, (y) 5′-gggcauaagguauuuaauuccaua-3′.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of aptamer expression on complementation of the Pol Its mutation in HIV-1 RT. Photographs show concentric dilution plates of strain BK148 with the following plasmids: (A) pHSG576, (B) pRT5, (C) pRT5 and p70.28.

TABLE 1.

Effects of aptamer expression on growth on HIV-1 RT complemented pol Its mutants in liquid culture end-point dilution assays

| Plasmids | RT gene/aptamer | Dilution from initial culturesa | ||||||

| 10−1 | 10−3 | 10−4 | 10−5 | 10−6 | 10−7 | 10−8 | ||

| pHSG576 | None/none | + | + | + | ± | − | − | − |

| pRT5 | Yes/none | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| pRT5 and pERLAC | Yes/vector | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| pRT5 and PERTPK1.1 | Yes/TPK1.1 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| pRT5 and p70.24 | Yes/70.24 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| pRT5 and p70.28 | Yes/70.28 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| pRT5 and p70.28min | Yes/28min | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

aGrowth at 37°C for 48 hr following dilution from initial cultures at densities of 8 × 108 cfu/mL.

Temperature sensitivity restored by RNA aptamers

Four aptamers were cloned individually into the expression vector pERLAC (Fig. 1 ▶). Aptamers 70.28 and 70.24 are 118-nt isolates selected to bind HIV-1 RT, whereas 70.28min is the 34-nt pseudoknot core of isolate 70.28 (Burke et al. 1996). Aptamer TPK1.1 is a related 33-nt pseudoknot aptamer (Tuerk et al. 1992), which has been reported to bind HIV-1 RT in solution with enhanced affinity (Kd ≈ 25 pM; Kensch et al. 2000). Plasmid-derived transcripts all contain a 28-nt 5′ leader and a 50-nt 3′ tail, 40 nt of which form the stable rrnB transcriptional terminator (Fig. 1 ▶). This design was intended to minimize nucleolytic degradation and to maximize the probability that nascent transcripts would present the aptamers to the intracellular environment in their native conformations. Nitrocellulose filter-binding assays of transcripts synthesized in vitro with these flanking sequences gave Kd values (KdTPK1.1 = 1.1 nM; Kd70.28 = 5.3 nM; Kd70.28min = 25 nM; Kd70.24 = 43 nM) that are similar to those originally reported for the core aptamers (Tuerk et al. 1992; Burke et al. 1996).

Aptamer expression plasmids were introduced into BK148 harboring plasmid pRT5. RT-expressing strains carrying the empty aptamer cassette (pERLAC) grew to the edges of spiral streak plates at both 30°C and 37°C, indicating that HIV-1 RT remains active in the presence of transcripts from pERLAC. Cells expressing aptamer 70.28min (Fig. 2C ▶) or any of the other aptamers (data not shown) grew normally at 30°C, but were restricted to the high-density centers of the spiral streak at 37°C. Similarly, end-point dilution assays demonstrated that these strains required at least three to four orders of magnitude higher initial cell density for growth in culture than did cells expressing HIV-1 RT alone (Table 1 ▶), suggesting little or no HIV-1 RT activity in cells expressing inhibitory RNA ap-tamers. HIV-1 RT complementation in BK148 at 37°C is thus blocked by individual expression of aptamer 70.24, 70.28, 70.28 min, or TPK1.1.

Quantification of intracellular aptamer concentrations

Quantitative measurements of intracellular aptamer RNA levels can help delineate the parameters that govern in vivo inhibition. To this end, total cellular RNA (RNAT) was isolated from each strain, applied to a membrane, and probed with radiolabeled oligonucleotides. Aptamer RNA was consistently detected using a probe complementary to the 5′ leader of the aptamer expression cassette common to all constructs (Fig. 1B ▶). Comparison with purified RNA standards revealed intracellular concentrations ranging from 76 ± 10 nM to 180 ± 47 nM (70–160 copies per cell) for all four aptamers (Table 2 ▶). These values are similar to RT concentrations measured previously (100 copies/cell; Kim and Loeb 1995). Control RNA expressed from the aptamer-free vector (pERLAC) was measured to be at a concentration of 179 ± 11 nM; thus, the growth of cells expressing this plasmid at 37°C cannot be attributed to failure to accumulate RNA, but rather to the absence of aptamer in the expressed RNA. As these RNA concentrations are well in excess of the measured Kd values for the aptamer-RT interactions, inhibitory RNA concentrations are therefore high enough to sequester most or all of the HIV-1 RT produced in the cell. Consistent with this interpretation, RT activity in cell-free extracts was reduced to the HIV RT− background level in cultures expressing both RT and aptamers (Table 3 ▶).

TABLE 2.

Steady-state concentration (nM) of aptamer RNAa

| Plasmids present in BK148 | Normalized to cell number | Normalized to rrnB signal |

| pERLAC + pRT5 | 174 ± 14 | 179 ± 11 |

| pERTPK1.1 + pRT5 | 108 ± 22 | 112 ± 17 |

| p70.24 + pRT5 | 200 ± 52 | 180 ± 47 |

| p70.28 + pRT5 | 75 ± 10 | 76 ± 10 |

| p28min + pRT5 | 91 ± 6 | 105 ± 7 |

aAll concentrations assume a cell volume of 1.5 μm3.

TABLE 3.

RT activity in cell-free extracts

| Cell-free extracts | Total RT activitya | Relative activity |

| BK148 alone (no plasmids) | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 1.0 |

| BK148 (pRT5) | 12.1 ± 2.9 | 6.4 |

| BK148 (pRT5, p70.28) | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.0 |

| BL21DE3 (pRT(p)) | 253.0 ± 46 | 133.0 |

aUnit activity defined as fmole of dTTP incorporated into TCA precipitable material • min−1 • μg protein−1.

Values are reported as the mean ± standard deviation reported based on at least three assays.

DISCUSSION

HIV-1 RT can be inhibited by RNA aptamers inside bacterial cells, as reported by loss of growth in a DNA polymerase I complementation assay. By extension, it should be possible to monitor aptamer–protein interactions for other essential proteins by assessing the growth of conditional null phenotypes. The four RNA aptamers in this study are expressed as components of small transcripts (94–208 nt). They all inhibit HIV-1 RT polymerase activity in vitro, and they all prevent HIV-1 RT complementation of BK148 at nonpermissive temperatures both on plates and in serial dilution assays (Fig. 2 ▶; Table 1 ▶). Aptamer-expressing BK148 cultures always grew at 30°C, as did an isogenic Pol+ strain (JS295) carrying any of the aptamer expression constructs at 30°C or 37°C. Thus, no other essential cellular function is significantly inhibited by these aptamers at either temperature.

The binding affinity and the relative expression levels of an aptamer and its target protein can profoundly influence the biological effects of aptamer expression (Burke and Nickens 2002). For high-affinity interactions, aptamer RNA concentration is more important than the precise value of Kd in determining the fraction of RT bound by aptamer. Western blot analysis of BK148 cells carrying plasmid pHIVRT (essentially identical to pRT5) gave estimates of ~100 copies of HIV-1 RT per induced cell (Kim and Loeb 1995; Kim 1997). Assuming a mean cell volume of 1.5 μm3/cell (Kubitschek and Friske 1986), this corresponds to a concentration of 110 nM for the RT. Intracellular concentrations of aptamer and control RNA were determined here to range between 76 and 180 nM (Table 2 ▶). Given the Kd values reported here for these aptamers in the context of their 5′ and 3′ flanking sequences (1–40 nM), approximately 50%–98% of the expressed HIV-1 RT is expected to be sequestered by aptamers. It is not known how much DNA polymerase activity the HIV-1 RT needs to provide for complementation of the Pol Its phenotype, or inversely, what fraction of the RT needs to be blocked to inhibit growth. However, the lack of RT activity in cell-free extracts from cells expressing both HIV-1 RT and aptamer relative to cells expressing HIV-1 RT only (Table 3 ▶), suggests that most of the RT is bound by aptamer.

Bioassays for screening new drugs have a long history, and their use for testing aptamer efficacy is a logical development. Whereas aptamers against HIV-1 RT have been available for 10 yr, their bioactivity has only recently been reported. As noted above, RNA aptamers show potent anti-viral activity in human cell culture. We have speculated that HIV-1 RT may not be able to mutate to aptamer resistant forms without adversely affecting viral replication activity (Burke et al. 1996). This hypothesis appears to have been born out in at least one instance (Fisher et al. 2002). The system described here offers for the first time a methodology to test this hypothesis by screening libraries of RT mutants for resistance to aptamer inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and medium

Genetic complementation experiments used the Pol Its E. coli B/r strain BK148 (recA718 polA12 fad751::Tn10 trpE65 uvrA155 mal− lon− sulA11; Witkin and Roegner-Maniscalco 1992). E. coli strain NM522 (Stratagene) was used for cloning and for plasmid construction. Luria broth and Difco nutrient broth were supplemented with chloramphenicol (30 μg/mL), carbenicillin (200 μg/mL), tetracycline (10 μg/mL), or IPTG (0.1 mM) as appropriate.

Plasmid construction

All plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Vector pERLAC is a derivative of pUHE-21.2 (Lanzer and Bujard 1988), a transcription-translation vector that is itself a derivative of the ColE1 replicon pBR322. Chloramphenicol resistance was removed by divergent PCR using oligonucleotides pUHE-PCR1 (5′-GGGGTACCCGGGATCTAAGTATCATTGTT-3′) and pUHE-PCR-2 (5′-GGGGTACCTGCAGAGCTCATAAAACGAAAGGCT CAGTC-3′). Digestion with KpnI (underlined) and ligation yielded a 2502-bp plasmid designated pER1 that retains a β-lactamase gene for selection. The lacO1 operator was restored using synthetic oligonucleotides to create plasmid pERLAC. Transcription of aptamers cloned into pERLAC is driven by a heterologous phage T7 promoter A1 (which utilizes E. coli RNA polymerase), combined with two lac operators (PA1-04/03) to generate transcripts of the form shown in Figure 1B ▶.

The gene for HIV-1 RT was amplified by PCR from plasmid p83-2 (AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program), which carries the pol gene from HIV-1 clinical isolate NY5 (Adachi et al. 1986; Gibbs et al. 1994). This fragment was cloned along with appropriate oligonucleotides into HindIII–BamHI-digested pHSG576, a low-copy number plasmid that utilizes a Pol I independent pSC101 origin of replication (Takeshita et al. 1987), to create the HIV-1 RT expression plasmid pRT5 (Fig. 1A ▶). This construct is nearly identical to another low-level RT expression vector, pHIVRT (Kim and Loeb 1995). Transcription of the HIV-1 RT gene is under the control of the lacP/O from the pHSG576 vector. Plasmid copy number for pRT5 was steady under the conditions used here, whereas copy number of the aptamer-encoding vectors diminished by 80% in BK148 compared with aptamer plasmid levels in the cloning strain NM522.

RNA detection and quantification

Total RNA (RNAT) was prepared from overnight cultures using a MasterPure RNA purification kit (Epicentre), then resuspended in ddH2O with RNasin (Promega) at 1 U/μL and stored at −80°C. RNA standards were transcribed in vitro from PCR-amplified templates derived from plasmids pERLAC (for RNA T7-Lac) or pERTPK1.1 (for RNA T7-TPK1.1). Slot blots were prepared using a Bio-Dot SF microfiltration apparatus with Zeta-Probe blotting membranes using a slight modification of the Epicentre protocol. RNAT, or standard RNA was mixed with yeast tRNA, so that each slot on the grid received 6 μg of RNA. Cell number per microgram of RNAT was determined from optical density of culture assuming 5 × 108 cells•mL−1 when A600nm = 1.0. Blotted membranes were probed with radiolabeled AptQuant oligonucleotide (Fig. 1A ▶). After washing off nonspecifically bound probe, the blot was dried and analyzed using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software. Calibration curves for converting PhosphorImager pixels to picomoles of target RNA were plotted using the signal from the standard RNA. A faint signal in RNAT prepared from BK148 carrying only plasmid pRT5 defined the nonspecific background associated with the AptQuant probe, and was subtracted from each sample before calculating aptamer concentrations for each strain.

After calculating the picomoles of aptamer RNA present in each applied sample, blots were stripped and reprobed with the rrnB1 probe specific for ribosomal RNA, allowing the rRNA to serve as an internal loading standard. Molar concentrations of aptamers inside cells were calculated from (1) the number of cells that contributed RNAT to a given blot, (2) the calculated moles of aptamer RNA detected, and (3) an assumed average cell volume of 1.5 μm3 for exponentially growing cultures in nutrient broth (Kubitschek and Friske 1986). Excluded volume due to intracellular molecular crowding was omitted from the calculation.

Reverse transcriptase assays and Kd determination

Duplicate reverse transcriptase assays were performed using cell-free extracts prepared from duplicate cultures as described previously (Hizi et al. 1988) using 20 μg of total protein per assay. Cells carrying plasmid pRT(p), an RT-overexpressing plasmid (gift of S. Hughes, National Cancer Institute), served as positive control for RT activity. Dissociation constants (Kd) were determined from nitrocellulose filter-binding assays as described (Burke et al. 1996) using gel-purified, radiolabeled aptamer RNA and purified HIV-1 RT carrying a His6 tag on its carboxyl terminus.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Hoffman for constructing plasmids pRT5 and pERLAC; Larry Loeb, Baek Kim, Joanne Sweasy, and John E. Hearst for plasmids and strains, and Daniel Held and Vanvimon Saksmerprome for critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a Beckman Young Investigator award and by grant AI45344 from the National Institutes of Health. The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- Adachi, A., Gendelman, H.E., Koenig, S., Folks, T., Willey, R., Rabson, A., and Martin, M.A. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59: 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreola, M.L., Pileur, F., Calmels, C., Ventura, M., Tarrago-Litvak, L., Toulmé, J.J., and Litvak, S. 2001. DNA aptamers selected against the HIV-1 RNase H display in vitro antiviral activity. Biochemistry 40: 10087–10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, D.H. and Nickens, D.G. 2002. Expressing RNA aptamers inside cells to reveal proteome and ribonome function. Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics 1: 169–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, D.H., Scates, L., Andrews, K., and Gold, L. 1996. Bent pseudoknots and novel RNA inhibitors of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase. J. Mol. Biol. 264: 650–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloin, L., Lehmann, M.J., Sczakiel, G., and Restle, T. 2002. Endogenous expression of a high-affinity pseudoknot RNA aptamer supresses replication of HIV-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 4001–4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, T.S., Joshi, P., and Prasad, V.R. 2002. Mutations that confer resistance to template-analog inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 reverse transcriptase lead to severe defects in HIV replication. J. Virol. 76: 4068–4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, J.S., Regier, D.A., and Desrosiers, R.C. 1994. Construction and in vitro properties of HIV-1 mutants with deletions in “nonessential genes.” AIDS Res. Human Retroviruses 10: 343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hizi, A., McGill, C., and Hughes, S.H. 1988. Expression of soluble, enzymatically active, human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase in Escherichia coli and analysis of mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85: 1218–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, P. and Prasad, V.R. 2002. Potent inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by template analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors derived by SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment). J. Virol 76: 6545–6557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensch, O., Connolly, B.A., Steinhoff, H., McGregor, A., Goody, R.S., and Restle, T. 2000. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase-pseudoknot RNA aptamer interaction has a binding affinity in the low picomolar range coupled with high specificity. J. Biol Chem. 275: 18271–18278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. 1997. Genetic selection in Escherichia coli for active human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase mutants. Methods Comp. Methods Enzymol. 12: 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. and Loeb, L.A. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase substitutes for DNA polymerase I in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92: 684–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B., Hathaway, T.R., and Loeb, L.A. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase: Functional mutants obtained by random mutagenesis coupled with genetic selection in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 4872–4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubitschek, H.E. and Friske, J.A. 1986. Determination of bacterial cell volume with a coulter counter. J. Bacteriol. 168: 1466–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzer, M. and Bujard, H. 1988. Promoters largely determine the efficiency of repressor action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85: 8973–8977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahvi, A., Sudarsan, N., Ebert, M.S., Zou, X., Brown, K.L., and Breaker, R.R. 2002. Genetic control by a metabolite binding mRNA. Chem. Biol. 9: 1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, D.J., Feigon, J., Hostomsky, Z., and Gold, L. 1995. High-affinity ssDNA inhibitors of the reverse transcriptase of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus. Biochemistry 34: 9599–9610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweasy, J. and Loeb, L. 1992. Mammalian DNA polymerase b can substitute for DNA polymerase I during DNA replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 1407–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita, S., Sato, M., Toba, M., Masahashi, W., and Hashimoto-Gotoh, T. 1987. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZa-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene 61: 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk, C., MacDougal, S., and Gold, L. 1992. RNA pseudoknots that inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89: 6988–6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werstuck, G. and Green, M.R. 1998. Controlling gene expression in living cells through small molecule-RNA interactions. Science 282: 296–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, W., Nahvi, A., and Breaker, R.R. 2002a. Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature 419: 952–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, W.C., Cohen-Chalamish, S., and Breaker, R.R. 2002b. An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding FMN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 15908–15913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin, E.M.V. and Roegner-Maniscalco, V. 1992. Overproduction of DnaE protein (a subunit of DNA polymerase III) restores viability in a conditionally inviable Escherichia coli strain deficient in DNA polymerase I. J. Bacteriol. 174: 4166–4168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]