Abstract

The generation of deletion mutants, including defective interfering viruses, upon serial passage of Spodoptera exigua multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (SeMNPV) in insect cell culture has been studied. Sequences containing the non-homologous region origin of DNA replication (non-hr ori) became hypermolar in intracellular viral DNA within 10 passages in Se301 insect cells, concurrent with a dramatic drop in budded virus and polyhedron production. These predominant non-hr ori-containing sequences accumulated in larger concatenated forms and were generated de novo as demonstrated by their appearance and accumulation upon infection with a genetically homogenous bacterial clone of SeMNPV (bacmid). Sequences were identified at the junctions of the non-hr ori units within the concatemers, which may be potentially involved in recombination events. Deletion of the SeMNPV non-hr ori using RecE/RecT-mediated homologous ET recombination in Escherichia coli resulted in a recombinant bacmid with strongly enhanced stability of virus and polyhedron production upon serial passage in insect cells. This suggests that the accumulation of non-hr oris upon passage is due to the replication advantage of these sequences. The non-hr ori deletion mutant SeMNPV bacmid can be exploited as a stable eukaryotic heterologous protein expression vector in insect cells.

Baculoviruses are large enveloped, circular double-stranded DNA insect viruses which are widely used as bioinsecticides in agriculture and forestry and can be genetically engineered to improve their effectiveness (2, 18). More recently, baculoviruses were shown to have potential as gene delivery vectors for gene therapy (12, 32, 45) or as vectors for surface display of complex eukaryotic proteins (6). Yet, their major application to date is as a viral vector for the expression of heterologous proteins in insect cells (19, 36). The prototypic and most intensively studied baculovirus, Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV), has been primarily used as an expression vector, while other baculoviruses may become exploited as well, especially when appropriate cell lines are available.

A major drawback in the large-scale production of baculoviruses as bioinsecticides or for heterologous protein production is the so-called passage effect. This effect is notable as a significant drop in production after prolonged virus passaging in insect cell culture (reviewed by Krell [25]) and is a result of the accumulation of defective interfering particles (DIs) (20). These DIs are rapidly generated in cell culture (39) and become predominant after prolonged passaging, meanwhile interfering with the replication of intact helper virus. However, the mechanism of the generation of DIs is still enigmatic, and the sequences involved are unknown.

DIs have retained cis-acting elements essential for baculovirus DNA synthesis, such as origins of replication (ori) (25). Transient virus-mediated plasmid replication assays demonstrated that baculovirus homologous regions (hrs) (21, 22, 28, 37), as well as baculovirus early promoter regions not containing hr sequences (49), have a putative ori function. In addition, these assays showed that other non-hrs, with structural similarities to eukaryotic oris, may have an ori function (11, 14, 23, 38). Their ori activity in vivo was recently demonstrated but was unfortunately not compared to the ori activity of hrs (7). Strikingly, AcMNPV DIs were enriched in such a non-hr ori (26, 27). This suggests a prominent role of baculovirus non-hr oris in the generation of DIs.

For large-scale or continuous production of heterologous eukaryotic proteins by use of the baculovirus expression system in insect cell bioreactors, the passage effect is a major obstacle. For prevention of the negative consequences of the passage effect, a genetically stable viral genotype is highly demanded. This may be achieved by selection for viruses with enhanced stability or higher polyhedron (or recombinant protein) production (42) or, alternatively, by site-directed mutagenesis of viral sequences putatively involved in the generation and/or maintenance of DIs. Therefore, we chose the non-hr ori sequence as a target for mutagenesis studies.

Compared to AcMNPV infections in widely used cell lines such as Sf21 and Sf9, the generation and predominance of Spodoptera exigua MNPV (SeMNPV) deletion mutants (including DIs) in various S. exigua cell lines occurs significantly faster (3, 11). This virus-cell system thus provides a better model system than AcMNPV to study the passage effect, the mechanism of DI generation, and the pivotal role of non-hr ori sequences therein.

In this paper we have studied the rapid passage effect during serial passaging of wild-type SeMNPV in the established S. exigua cell line Se301 (9). To monitor the generation of DI genomes over passage and to study the role of the non-hr ori sequences in this process, a full-length infectious clone of SeMNPV propagated in Escherichia coli (bacmid) was constructed and used in serial passage experiments. This revealed the pivotal role of the non-hr ori in the genesis of DIs and led to the generation of a recombinant SeMNPV bacmid with enhanced stability in cultured insect cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, insects, and virus.

The S. exigua cell line Se301 (8, 9) was donated by T. Kawarabata (Institute of Biological Control, Kyushu University, Kyushu, Japan) and was propagated at 27°C in Grace's supplemented medium (Gibco BRL) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL). Fourth-instar S. exigua larvae were infected by contamination of artificial diet with 4 × 105 SeMNPV-US1 (5) polyhedra per larva (43). Hemolymph was collected as previously described (17) and was defined as the passage zero (P0) budded-virus (BV) inoculum to initiate serial passage in cultured Se301 cells. Serial undiluted passaging was carried out as previously described (39). Infectious BV titers were determined using the endpoint dilution assay (47).

DNA isolation, Southern hybridization, colony lift, molecular cloning, and sequencing.

Intracellular viral (ICV) DNA and BV DNA were isolated as previously described (44). Digested viral DNA was run overnight in ethidium bromide-stained 0.6% agarose gels, and Southern blotting was performed by standard capillary upward blotting (40) using Hybond-N (Amersham Pharmacia) filters. As a DNA size marker, λ-DNA digested with EcoRI/HindIII/BamHI was used. Randomly primed DNA probes for Southern hybridization were made using a digoxigenin nonradioactive nucleic acid labeling and detection system (Roche). PCR products (927 bp) of the SeMNPV non-hr ori were made with reverse primer DZ127, 5′-CATCGATGCGTACGTGACTTTC-3′ (nucleotides [nt] 84027 to 84048 [16]), and forward primer DZ128, 5′-CCTTGCGTTCCTTTGGTG-3′ (nt 83122 to 83139); purified using a High Pure PCR purification kit (Roche); and digoxigenin labeled overnight. Hybridization and colorimetric detection with nitroblue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Gibco BRL) were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Hypermolar viral XbaI bands were cut from the gel, purified with Glassmax (Gibco BRL), and cloned into pUC19 by electrotransformation of E. coli DH5α using standard methods (40). A colony lift assay (40) was used to isolate the cloned submolar 5.3-kb fragment using the same probe as described above. Automatic sequencing was performed using an ABI prism 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer) at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Wageningen University. Sequence analyses were performed using BLAST (1) from the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group computer programs (release 10.0).

Construction of bacmid cloning vector.

The bacmid vector for direct cloning of SeMNPV was constructed by PCR using the Expand long-template PCR system (Roche). Custom made primers (Gibco BRL) were designed using DNAstar Primerselect and were based on the sequence of AcMNPV transfer plasmid pVL1393 (29), which was the backbone of the transfer vector pMON14272 used to construct the AcMNPV bacmid bMON14272 (30). Primers DZ113 (5′-CCTT CCTGAGGTACCTTCTAGAATTCCGGAG-3′) and DZ114 (5′-CCTTCCTCAGGCCGGGTCCCAGGAAAGGATC-3′) were oppositely directed to sequences flanking the BglII cloning site of pVL1393 and contained additional Bsu36I restriction sites (italics) at their 5′ ends for circularization. DZ114 also contained an internal SanDI restriction site (underlined) for direct cloning into SanDI-linearized SeMNPV-US1 DNA. The template for PCR was purified AcMNPV bacmid bMON14272 (30) DNA from the Bac-to-Bac Kit (Gibco BRL). The resulting 8.5-kb PCR product was cloned into the 3.5-kb pCR-XL-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), digested with Bsu36I, self-ligated, and cloned into electrocompetent DH10β E. coli cells. The bacmid cloning vector obtained was designated BAC-Bsu36I, and its identity was verified by restriction analysis.

Direct cloning of SeMNPV-US1 as bacmid.

SeMNPV-US1 DNA for direct cloning was purified using alkaline treatment of polyhedra and by previously described methods (36). Two micrograms of viral SeMNPV-US1 DNA was linearized at the polyhedrin locus by digestion with 10 U of SanDI (Stratagene) for 16 h at 37°C. The restriction enzyme was heat inactivated for 15 min at 65°C. One microgram of bacmid cloning vector BAC-Bsu36I was digested with 10 U of SanDI in a total volume of 35 μl for 3 h at 37°C. The 8.5-kb vector was dephosphorylated using 1 U of HK Thermolabile Phosphatase (Epicentre). The enzymes were heat inactivated for 15 min at 65°C prior to gel purification of the linearized cloning vector DNA with Glassmax (Gibco BRL). Ligation was performed for 16 h at 15°C with approximately 500 ng of linearized SeMNPV DNA and 25 ng of linearized vector DNA in a total volume of 20 μl using 6 U of T4 DNA ligase (Promega). Electrocompetent E. coli DH10β cells (Gibco BRL) were transformed with 2 μl of ligation mix at 1.8 kV using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser. The transformed cells were recovered in SOC medium (40) for 45 min at 37°C and spread on agar plates containing kanamycin. An SeMNPV bacmid with the correct restriction profile was selected from 111 putative SeMNPV bacmid clones and was designated SeBAC10.

Deletion of SeMNPV non-hr ori by ET recombination in E. coli.

For deletion mutagenesis of the active essential domain of the non-hr ori of SeMNPV-US1 bacmid SeBAC10, 68- to 70-bp primers were designed with 50-bp 5′ ends flanking the deletion target region on the SeMNPV genome. Forward primer DZ153 was 5′-CATTTACTCGAAAACACTGTACACTTCGTCAAAATAAATGACGCAATATTTTTAAGGGCACCAATAACTG-3′, with a viral flanking sequence from nt 83237 to 83286 according to the SeMNPV complete genome sequence (16). Reverse primer DZ154 was 5′-ATTTCAAAAATTAGAATCAAAACCCAATTTGCCGGCAACGTTTTAATATTTTCCTGTGCGACGGTTAC-3′, with a viral flanking sequence from nt 83981 to 83932. The locus to be deleted, which is the essential domain of the SeMNPV non-hr ori, is defined by two SspI sites (11). These SspI restriction sites are included in the primers (underlined). The 3′ ends of the primers anneal to the chloramphenicol gene of pBeloBAC11 (41, 48) from nt 735 to 1671. PCR on pBeloBAC11 was performed using the Expand long-template PCR system (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol, giving a product of 1,036 bp. The PCR product was purified using the High pure PCR purification kit (Roche), cut with DpnI to eliminate residual pBeloBAC11 template, phenol-chloroform extracted, and ethanol precipitated. Approximately 0.5 μg of PCR product was used for transformation of electrocompetent E. coli DH10β containing both SeBAC10 and homologous recombination helper plasmid pBAD-αβγ.

DH10β cells containing SeBAC10 were heat shock transformed with pBAD-αβγ (34) and subsequently made electrocompetent according to the method of Muyrers et al. (34). Briefly, 70 ml of Luria-Bertani medium was inoculated with 0.7 ml of an overnight culture. At an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1 to 0.15, ET protein expression from pBAD-αβγ was induced by the addition of 0.7 ml of 10% l-arabinose. The cells were harvested at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3 to 0.4 and made electrocompetent by three subsequent washes with ice-cold 10% glycerol. The cells were transformed with the purified PCR product in 2-mm-diameter electroporation cuvettes (Eurogentec) using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (2.3 kV, 25 μF, 200 Ω). The cells were resuspended in 1 ml of Luria-Bertani medium and incubated for 1 h at 37°C and subsequently spread on agar plates containing kanamycin and chloramphenicol. The altered genotype of the recombinant bacmid, designated SeBAC10Δnonhr, was confirmed by PstI digestion and PCR. The genomic PstI-I fragment of SeBAC10 (7,017 bp) was anticipated to be 286 bp bigger in SeBAC10Δnonhr, giving a fragment of 7,303 bp (Fig. 4). PCR was performed with forward primer DZ127 and reverse primer DZ128 as previously described. The PCR product of 1,213 bp was cloned into pGEM-Teasy (Promega) and completely sequenced, revealing that recombination had occurred precisely at the anticipated locus via the 50 flanking nucleotides.

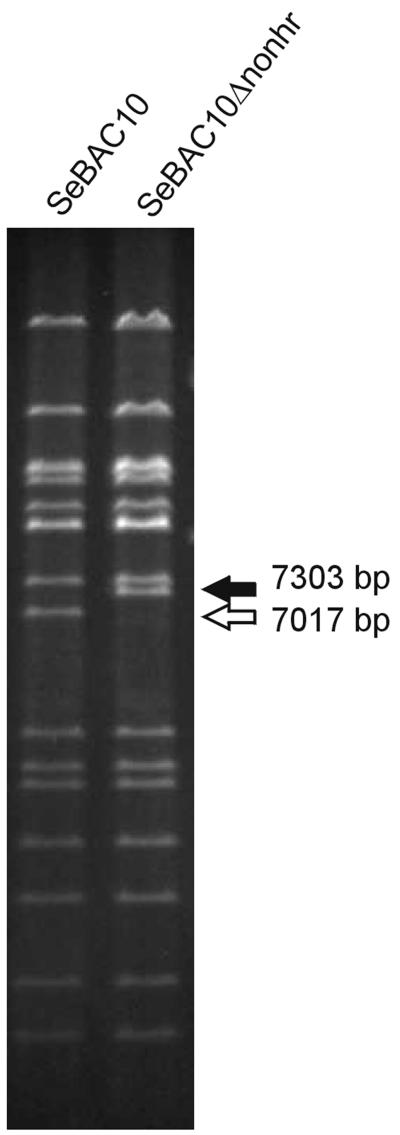

FIG. 4.

Restriction profile (PstI) of parental SeMNPV bacmid SeBAC10 and the non-hr ori deletion mutant SeBAC10Δnonhr. The genomic PstI-I fragment containing the non-hr ori (7,017 bp) and the PstI fragment with the Cmr gene insertion (7,303 bp) are indicated.

Reconstitution of the SeMNPV polyhedrin gene by pFastBAC1 donor plasmid.

To reconstitute the polyhedrin gene in SeMNPV bacmids SeBAC10 and SeBAC10Δnonhr, donor plasmid pFB1Sepol was constructed. The pFastBac1 vector (Gibco BRL) was digested with SnaBI and HindIII to delete the AcMNPV polyhedrin promoter and the multiple cloning site. The SeMNPV polyhedrin gene with its own promoter and the first putative transcription termination signal (46) was amplified by the Expand long-template PCR system (Roche) using forward primer DZ138, 5′-CCCCCGGGTATATACTAGACGCGATTAC-3′ (nt 135475 to 135494), and reverse primer DZ139, 5′-CCAAGCTTTGTAATACTTACCTTTTGTG-3′ (nt 757 to 776), containing SmaI and HindIII restriction sites (italics), respectively. The resulting 930-bp fragment was cloned into a pGEM-Teasy vector (Promega), sequenced, and subsequently cloned as a SmaI/HindIII fragment into the pFastBac1 vector to generate pFB1Sepol. The protocol from the Bac-to-Bac manual (Gibco BRL) was followed to transpose the SeMNPV polyhedrin gene from pFB1Sepol into the attTn7 transposon integration site of SeMNPV bacmids SeBAC10 and SeBAC10Δnonhr to generate SeBAC10ph and SeBAC10phΔnonhr, respectively.

Transfection of SeMNPV bacmids.

Se301 cells were seeded in a six-well tissue culture plate (Nunc) at a confluency of 25% (5 × 105 cells). Transfection was performed with approximately 1 μg of SeBAC10ph or SeBAC10phΔnonhr DNA using 10 μl of Cellfectin (Gibco BRL). As a positive control, 1 μg of SeMNPV-US1 DNA was transfected as well. After 5 and 7 days, polyhedra were formed by the cells transfected with SeMNPV-US1 and the bacmids, respectively. BV-containing supernatant (defined as P1) and infected cells were harvested 14 days posttransfection (90% polyhedron-containing cells).

RESULTS

Serial passage of SeMNPV in Se301 insect cells.

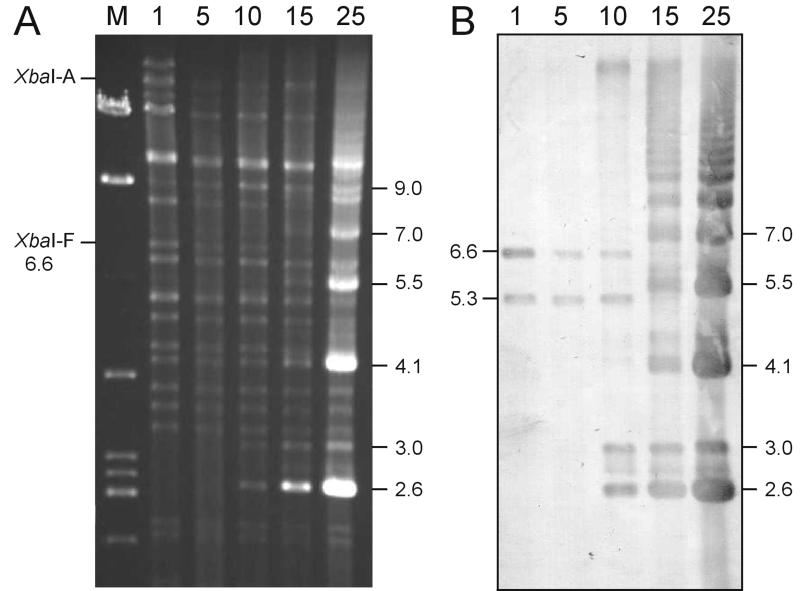

SeMNPV-US1 was serially passaged 25 times in the S. exigua cell line Se301 with BV from infectious hemolymph, defined as P0 inoculum. A decrease of polyhedron production was observed after fewer than five passages, indicating a dramatic passage effect. ICV DNA was purified and subjected to XbaI (Fig. 1A) digestion. A rapid reduction of the major genomic XbaI-A fragment was observed (Fig. 1A). At the same time, a novel XbaI fragment of about 9 kb became more abundant and was cloned and sequenced. This fragment was already present in the P1 DNA and appeared to consist of the remnants of the XbaI-A fragment as a result of a 26.5-kb deletion (from nt 15301 to 41759), according to the complete genome sequence of SeMNPV (16). The occurrence of mutants with deletions in this particular genomic region is a common phenomenon of SeMNPV infection in cell culture, but these deletions do not compromise BV or protein production (3, 10). In vivo, such deletion mutants also exist and can act as parasitic genotypes (33).

FIG. 1.

Restriction profile of intracellular DNA of wild-type SeMNPV-US1 upon passaging (P1 to 25) in Se301 insect cells. (A) DNA digested with XbaI and run in a 0.6% agarose gel. Passage numbers are indicated above the lanes, and the viral genomic XbaI-A and -F fragments are indicated on the left. Lane M contains a λ/EcoRI/BamHI/HindIII DNA size marker. Sizes (in kilobases) of the hypermolar novel bands (2.6 to 7.0) and the novel 9-kb fragment are indicated on the right. (B) Southern blot using the SeMNPV non-hr ori (nt 83122 to 84048) as a probe. The viral genomic 6.6-kb XbaI-F (containing the non-hr ori) and an additional hybridizing 5.3-kb band are indicated on the left.

Analysis of hypermolar bands.

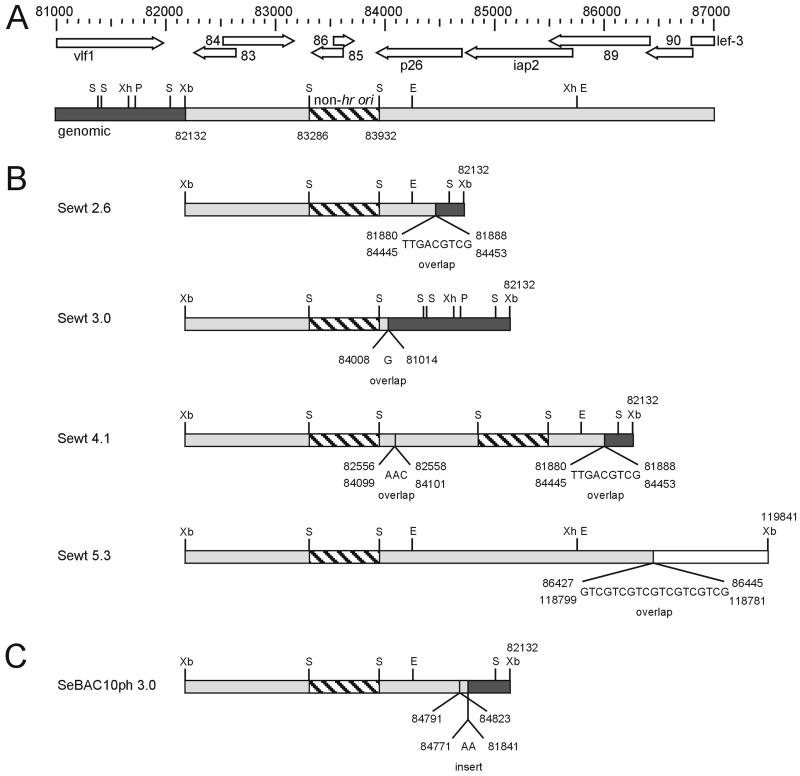

Hypermolar fragments accumulated in Se301 cells from P10 onwards, and they were visualized as XbaI restriction fragments of 2.6 and 3.0 kb in agarose gels (Fig. 1A). From P15 onwards also, bands of 4.1, 5.5, and 7.0 kb and more became hypermolar. The abundant 2.6-, 3.0-, and 4.1-kb XbaI bands were cloned and sequenced, and it was found that the XbaI sites on either side of the cloned inserts corresponded to the SeMNPV XbaI restriction site at position 82132, according to the complete sequence of SeMNPV (16). Most interestingly, both the 2.6- and 3.0-kb fragments contained the entire SeMNPV non-hr origin of DNA replication (nt 83286 to 83932 [11]) and a junction of sequences flanking this non-hr ori (Fig. 2). The borders and the junction of the 4.1-kb fragment appeared to be identical to those of the 2.6-kb fragment (Fig. 2B). The difference in size is a consequence of a duplicated non-hr ori present in this 4.1-kb fragment. Noteworthy is the presence of an overlapping stretch of 9 bp at the junction site in the 2.6- and 4.1-kb fragment (Fig. 2B), which in the complete SeMNPV genome is present on either side of the non-hr ori, leaving 2.6 kb in between. Because of the presence of a junction site and the same XbaI (position 82132) on either side of the fragments, it was concluded that the hypermolar fragments must exist in the ICV DNA preparation either as DNA minicircles or as tandem repeats in a larger concatenated form.

FIG. 2.

Schematic overview of the genetic organization of hypermolar and other non-hr ori hybridizing bands compared to the complete SeMNPV genome. (A) Genetic organization of the genomic DNA with nucleotide positions according to the complete SeMNPV genome (16). Arrows represent the respective ORFs. Solid and light-grey boxes refer to sequences on either side of XbaI (Xb) 83132, containing SspI (S), PstI (P), EcoRI (E), and XhoI (Xh) sites. The non-hr ori is presented as a hatched box between the two SspI sites (11). (B) Genetic arrangement of hypermolar 2.6-, 3.0-, and 4.1-kb fragments of SeMNPV-US1 (Sewt) and a nonhypermolar cohybridizing 5.3-kb fragment (genomic fragment of a SeMNPV deletion mutant) in the Southern blots. Nucleotide positions and sequence overlaps and insertions are indicated at the junction sites. (C) Genetic arrangement of the hypermolar 3.0-kb fragment of SeBAC10ph, containing two junctions.

To investigate whether the other hypermolar bands of 5.5 kb, 7.0 kb, and more also contained the non-hr ori, a Southern blot was made with a non-hr ori probe. The result (Fig. 1B) showed that these fragments hybridized strongly to the probe, and therefore it was concluded that a range of molecules of different sizes containing the SeMNPV non-hr ori predominated upon serial passage.

In addition to the non-hr ori containing the genomic XbaI-F fragment of 6.6 kb, an unexpected additional band of 5.3 kb hybridizing to the non-hr ori probe (Fig. 1B [see also Fig. 3]) became submolar from P15 onwards. Sequencing revealed that the 5.3-kb fragment consisted of two joined, but distantly located, sequences from the SeMNPV genome (Fig. 2B). The ends of the fragment corresponded to XbaI sites at positions 82132 and 119846, respectively. The junction between the two fragments was formed by an overlapping sequence stretch of 19 bp, containing multiple GTC repeats, located at positions 86426 to 86446 and 118807 to 118780. The presence of this 5.3-kb band in the wild-type SeMNPV DNA was confirmed by Southern hybridization.

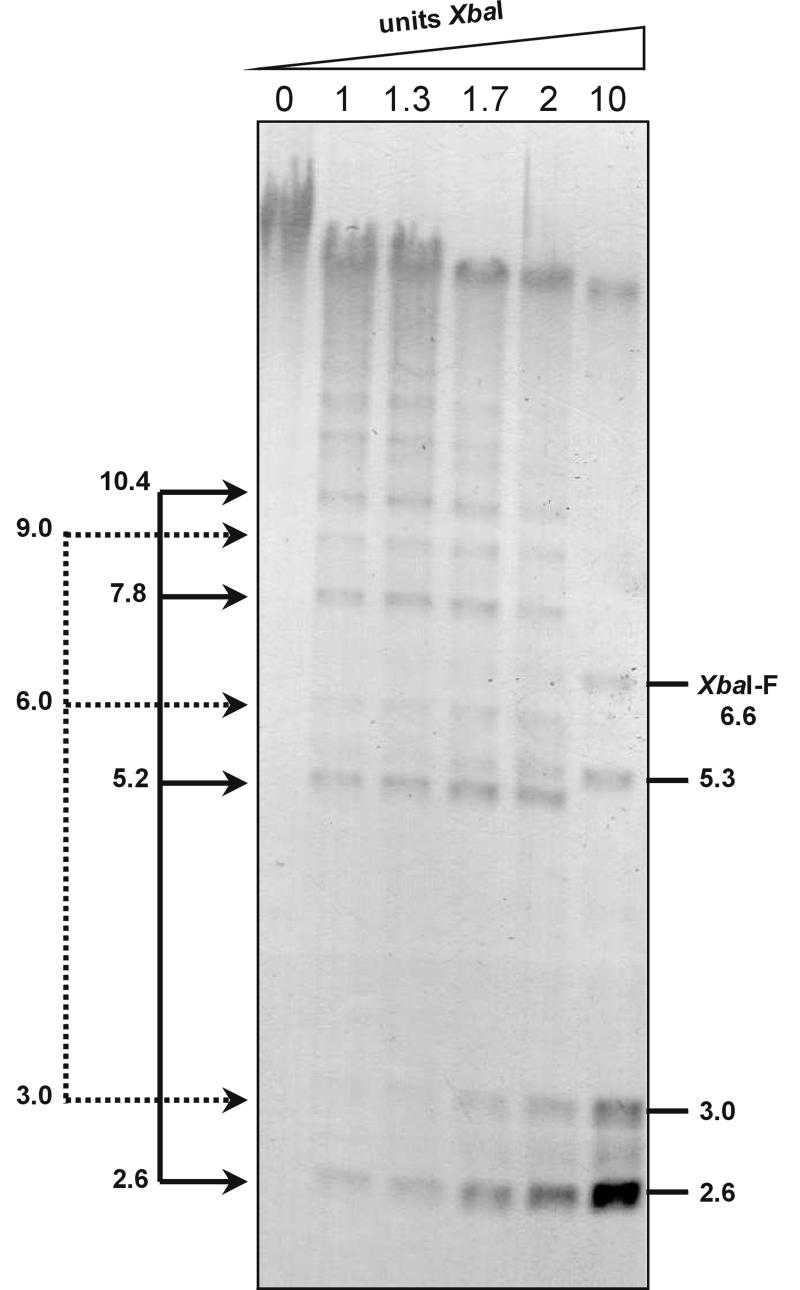

FIG. 3.

Replicative form of the hypermolar 2.6- and 3.0-kb XbaI fragments by partial digestion of ICV SeMNPV-US1 DNA of P10, using increasing amounts of XbaI. On the right the genomic 6.6-kb XbaI-F and the additional 5.3-kb band as well as the hypermolar XbaI bands of 2.6 and 3.0 kb are indicated. On the left the multimers of the 2.6- and 3.0-kb XbaI fragments are indicated by arrows.

Replicative-form hypermolar 2.6- and 3.0-kb XbaI fragments.

To investigate whether the abundant XbaI fragments of 2.6 and 3.0 kb exist as minicircles or as tandem repeats in a larger concatenated form, ICV DNA of P10 (at a stage when only the 2.6- and 3.0-kb bands were abundant) was subjected to partial digestion with XbaI, using increasing amounts of restriction endonuclease during digestion for 20 min. Hybridization was performed with the same non-hr ori probe as described above (Fig. 3). The partial XbaI digests of P10 viral DNA showed a stepladder of multimers of the 2.6- and 3.0-kb bands. This suggests that the accumulation of the SeMNPV non-hr ori occurs via high-molecular-weight concatemers of tandem repeats of different sizes. This is likely to be the case not only for the 2.6- and 3.0-kb fragments but also for the 4.1-, 5.5-, 7.0-kb, and larger fragments from P15 onwards.

Serial passage of SeMNPV bacmids in Se301 insect cells.

A genetically homogeneous SeMNPV bacmid (SeBAC10) and a derived non-hr ori deletion mutant (SeBAC10Δnonhr) were constructed (Fig. 4) to determine whether non-hr ori concatemers are generated de novo in cell culture or preexist and become selectively amplified and whether virus stability might be enhanced by deletion of this non-hr ori.

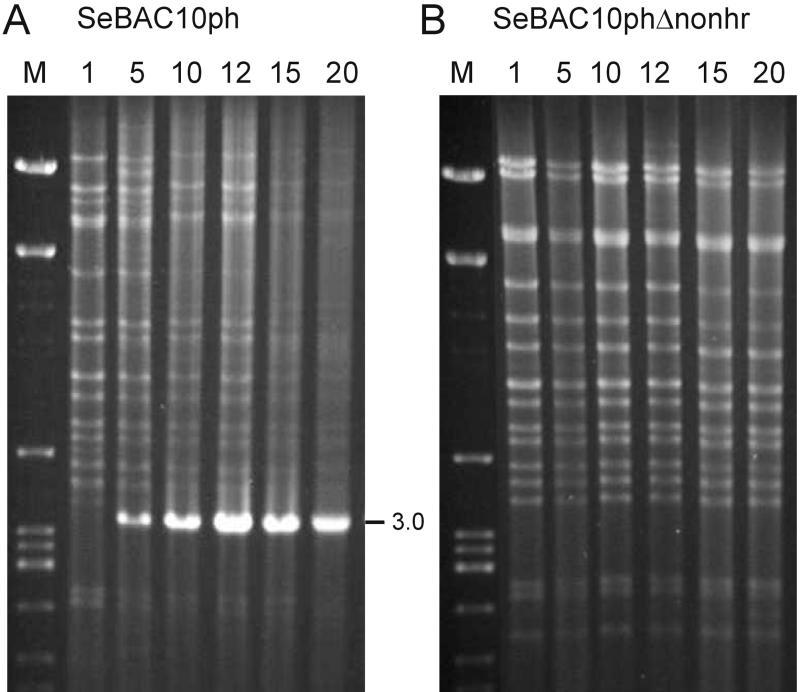

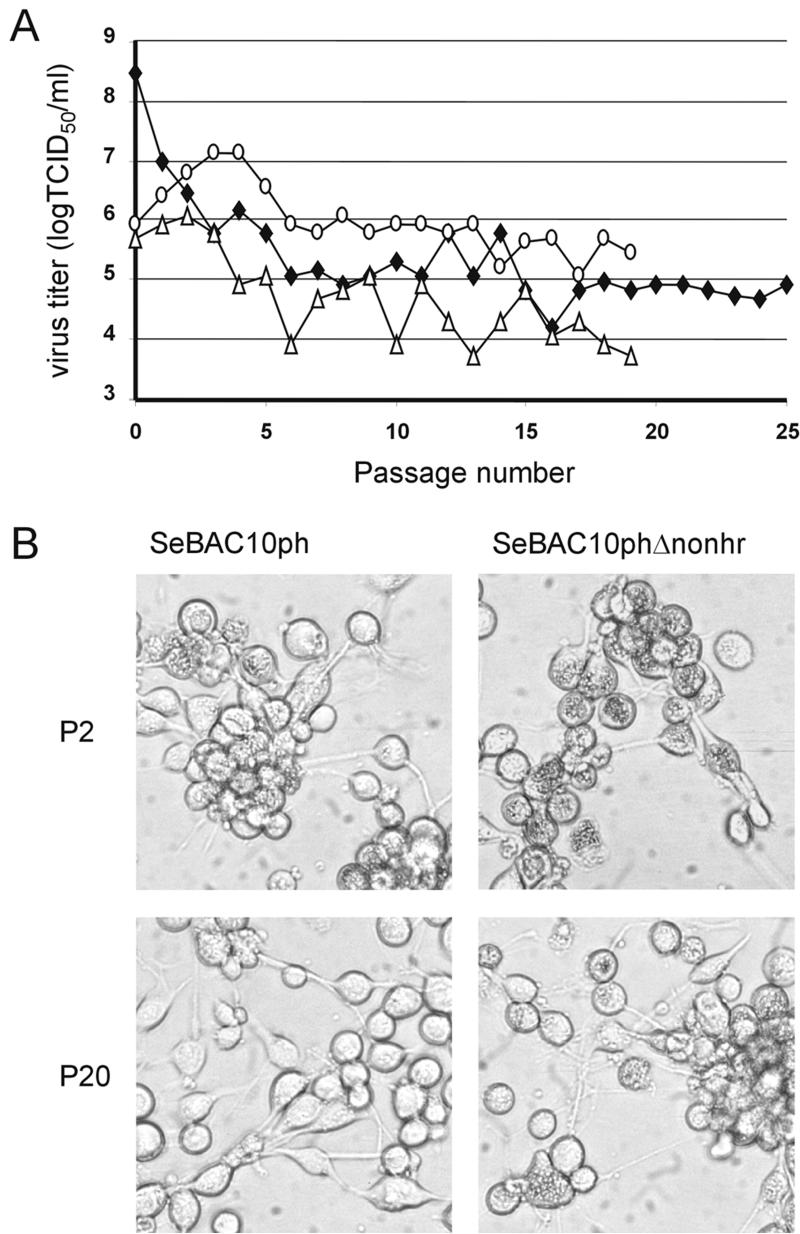

Prior to serially passaging the bacmid-derived BVs in cell culture, the polyhedrin gene was reintroduced. After transfection of Se301 cells, the BV-containing supernatant was defined as the P1 virus stock and was used to initiate serial undiluted passage. ICV DNA was purified and digested with XbaI. Similar to SeMNPV-US1 (this study and references 3 and 10), deletions in XbaI-A occurred for both bacmids SeBAC10ph and SeBAC10phΔnonhr (Fig 5). The deletion in SeBAC10phΔnonhr was mapped as a junction overlap of 3 nt (AAC) from 20162, 20163, or 20164 to 36396, 36397, or 36398, spanning open reading frames (ORFs) 17 to 35. From P6 onward, a small hypermolar XbaI fragment of 3.0 kb was visible in DNA preparations of SeBAC10ph (Fig. 5A). This fragment was cloned and sequenced and appeared to contain the non-hr origin of DNA replication and a junction sequence (Fig. 2c) also observed with the SeMNPV-US1 wild type (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the analysis of ICV DNA from SeBAC10phΔnonhr-infected cells did not reveal any accumulation of hypermolar fragments (Fig. 5B). SeBAC10phΔnonhr BV titers remained at higher levels throughout the entire period of serial passaging than those of SeBAC10ph and SeMNPV-US1 wild type (Fig. 6A). Polyhedron production of SeBAC10phΔnonhr remained constant for at least 20 passages, in contrast to SeBAC10ph (Fig. 6B). These results demonstrated that absence of the non-hr ori strongly increased the stability of the SeMNPV genome in Se301 insect cells.

FIG. 5.

Restriction profile (XbaI) of ICV DNA of serially passaged SeMNPV bacmids SeBAC10ph (A) and SeBAC10phΔnonhr (B) in Se301 insect cells. Passage numbers (top) and the hypermolar band of 3.0 kb (SeBAC10ph) are indicated.

FIG. 6.

(A) Titers of serially passaged BV of SeMNPV-US1 (⧫), SeBAC10ph (▵), and SeBAC10phΔnonhr (○). TCID50, 50% tissue culture infective dose. (B) Pictures of infected Se301 insect cells with SeBAC10ph and SeBAC10phΔnonhr at P2 and P20, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The rapid accumulation of DI particles with DNA containing hypermolar non-hr oris appears to be an artifact of serial passage of SeMNPV in Se301 cells and the major cause of the decrease of virus and polyhedron production. Ultimately, these hypermolar molecules form the majority of the viral DNA. By partial digestion, we showed that these molecules exist as high-molecular-mass concatemers, in agreement with a supposed rolling-circle mechanism for baculovirus DNA replication (24, 28, 35, 50). Their rapid multiplication, together with previous data from in vitro replication assays (11), provides support for the view that the SeMNPV non-hr ori might be a genuine origin of DNA replication.

In order to elucidate whether these non-hr ori concatemers were newly formed in Se301 insect cells or, alternatively, only accumulated from a genetically heterogeneous wild-type isolate, a full-length infectious clone (bacmid) of SeMNPV was constructed. Such a bacmid could be stably maintained as a single-copy bacterial artificial chromosome in E. coli DH10β and used as a starting material in passage experiments in insect cells (30, 39). Transfection of Se301 insect cells with SeBAC10ph (with a reintroduced intact polyhedron gene) showed normal polyhedron production, but serial passage again resulted in a decrease of viral titers and polyhedron production and the rapid accumulation of non-hr ori containing molecules.

Since the non-hr ori could be removed from the viral DNA without affecting virus replication, we must conclude that this non-hr ori is not essential. The two minor ORFs 85 and 86 within the non-hr are also nonessential. These ORFs do not have known baculovirus or other homologues, and it is unknown whether they are transcriptionally active. Furthermore, deletion of this non-hr ori strongly enhanced the genomic stability in cell culture. Transfection of Se301 cells with the non-hr ori deletion mutant bacmid SeBAC10phΔnonhr gave normal polyhedron production and high viral titers (Fig. 6), which were maintained for up to at least 20 passages. Together with an unchanged restriction profile from P1 to P20, these results indicate that this recombinant has an enhanced stability in cell culture compared to both wild-type SeMNPV and the parental bacmid SeBAC10ph. The increased overall stability is probably not due to an increase in intrinsic stability of the SeMNPV genome by itself, but rather a consequence of the lack of a cis-acting element (non-hr ori) that has a strong replicative advantage during baculovirus DNA replication.

Our findings with SeMNPV are in line with the results from Lee and Krell (26, 27), who demonstrated that AcMNPV DIs at P81 largely consisted of reiterations of about 2.8 kb of the standard genome, which was later shown to contain an active non-hr origin of DNA replication (7, 23). In addition, previous work on AcMNPV showed that DIs could also be enriched in hrs (21). These observations suggest that reiteration and predominance of baculovirus hrs but particularly non-hr oris, which are complex structures comprising multiple direct and inverted repeats, are more common phenomena upon multiple passage and may contribute to a rapid passage effect. Single copies of non-hr oris, which resemble eukaryotic oris based on structural similarities (4), have been identified in many other baculovirus genomes by transient-replication assays (Orgyia pseudotsugataNPV [38] and Spodoptera littoralis MNPV [14, 15]) or based on sequence and structural similarity only (Bombyx moriNPV [24], Busura suppressaria NPV [13], and Cydia pomonella granulovirus [31]). The conservation of non-hr oris in baculovirus genomes implies an important (biological) role in virus replication and may be related to viral latency and persistence in insect populations. The resemblance to eukaryotic oris suggests that baculoviruses may have obtained these sequences from the host genomes to be able to replicate in the insect without the requirement for virus-encoded replication factors.

At the junctions of non-hr ori concatenated molecules and junctions of major genomic deletions, sequence overlaps of 1 up to 19 bp were found, potentially involved in the causative recombination mechanism. The sequence of the additional 5.3-kb fragment in the Southern blots showed a 19-bp overlap at the deletion junction, consisting of multiple GTC repeats (Fig. 2B). These GTC repeats of up to 27 bp were found scattered throughout the SeMNPV genome on both strands and were more frequent than expected on a random basis. For the 2.6-kb XbaI fragment concatemers, a 9-bp TTGACGTCG overlap from flanking sequences was found at the junction site (Fig. 2B). Also, this repeat was found more frequently (12 times) in the genome than expected on a random basis (<1). The 9-bp overlap implies that the concatemers of the 2.6-kb fragment were generated during serial passage by looping and subsequent excision (homologous recombination) of non-hr ori containing genomic DNA, followed by continued replication and consequent concatenation of this intervening region. The same 9-bp overlap was found at the junction of the 4.1-kb fragment, which contains a duplicated non-hr ori (Fig. 2). This suggests that the 4.1-kb fragment was generated from the 2.6-kb molecule by another recombination event and rapidly became hypermolar because of the presence of two copies of the non-hr ori. This hypothesis is consolidated by the appearance of the 4.1-kb fragment in passages later than the 2.6-kb fragment (Fig. 1A). For the other junctions, smaller overlaps (1 or 3 bp) or even insertions were found, which was also demonstrated for AcMNPV DIs in an earlier study (39), suggesting that the same recombination mechanisms are involved.

The strategy of deletion of sequences that have a replicative advantage, accumulate upon serial passage, and interfere with virus and protein production (e.g., non-hr oris) may now be applied for other baculoviruses as well and will contribute to the solution of problems associated with large-scale applications using baculovirus expression vectors for protein production in insect cells. In further studies we plan to map the sequences in the SeMNPV non-hr ori involved in the generation of DIs in more detail by reintroducing mutant SeMNPV non-hr oris in SeMNPV bacmids. In addition, we want to investigate whether the deletion of the non-hr ori affects baculovirus persistence in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank U. H. Koszinowski and M. Wagner for their generous donation of pBAD-αβγ.

This research was supported by the Technology Foundation STW (grant no. 790-44-730), the applied science division of NWO, and the technology program of the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, B. C., L. A. Brennan, P. M. Dierks, and I. E. Gard. 1997. Commercialization of baculoviral insecticides, p. 341-387. In L. K. Miller (ed.), The baculoviruses. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Dai, X. J., J. P. Hajos, N. N. Joosten, M. M. van Oers, W. F. IJkel, D. Zuidema, Y. Pang, and J. M. Vlak. 2000. Isolation of a Spodoptera exigua baculovirus recombinant with a 10.6 kbp genome deletion that retains biological activity. J. Gen. Virol. 10:2545-2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DePamphilis, M. L. 1993. Eukaryotic DNA replication: anatomy of an origin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62:29-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelernter, W. D., and B. A. Federici. 1986. Isolation, identification, and determination of virulence of a nuclear polyhedrosis virus from the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Environ. Entomol. 15:240-245. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grabherr, R., W. Ernst, C. Oker Blom, and I. Jones. 2001. Developments in the use of baculoviruses for the surface display of complex eukaryotic proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 19:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habib, S., and S. E. Hasnain. 2000. Differential activity of two non-hr origins during replication of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus genome. J. Virol. 74:5182-5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hara, K., M. Funakoshi, K. Tsuda, and T. Kawarabata. 1993. New Spodoptera exigua cell lines susceptible to Spodoptera exigua nuclear polyhedrosis virus. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 29:904-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara, K., M. Funakoshi, and T. Kawarabata. 1995. A cloned cell line of Spodoptera exigua has a highly increased susceptibility to the Spodoptera exigua nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:1111-1116. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heldens, J. G., E. A. van Strien, A. M. Feldmann, P. Kulcsar, D. Muñoz, D. J. Leisy, D. Zuidema, R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1996. Spodoptera exigua multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus deletion mutants generated in cell culture lack virulence in vivo. J. Gen. Virol. 77:3127-3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heldens, J. G., R. Broer, D. Zuidema, R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1997. Identification and functional analysis of a non-hr origin of DNA replication in the genome of Spodoptera exigua multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1497-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann, C., V. Sandig, G. Jennings, M. Rudolph, P. Schlag, and M. Strauss. 1995. Efficient gene transfer into human hepatocytes by baculovirus vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:10099-10103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu, Z. H., B. M. Arif, J. S. Sun, X. W. Chen, D. Zuidema, R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1998. Genetic organization of the HindIII-I region of the single-nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus of Buzura suppressaria. Virus Res. 55:71-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, J., and D. B. Levin. 1999. Identification and functional analysis of a putative non-hr origin of DNA replication from the Spodoptera littoralis type B multinucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2263-2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, J., and D. B. Levin. 2001. Expression, purification and characterization of the Spodoptera littoralis nucleopolyhedrovirus (SpliNPV) DNA polymerase and interaction with the SpliNPV non-hr origin of DNA replication. J. Gen. Virol. 82:1767-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IJkel, W. F., E. A. van Strien, J. G. Heldens, R. Broer, D. Zuidema, R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1999. Sequence and organization of the Spodoptera exigua multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 80:3289-3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IJkel, W. F., M. Westenberg, R. W. Goldbach, G. W. Blissard, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2000. A novel baculovirus envelope fusion protein with a proprotein convertase cleavage site. Virology 275:30-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inceoglu, A. B., S. G. Kamita, A. C. Hinton, Q. H. Huang, T. F. Severson, K. D. Kang, and B. D. Hammock. 2001. Recombinant baculoviruses for insect control. Pest Manag. Sci. 57:981-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King, L. A., and R. D. Possee. 1992. The baculovirus expression system. Chapman and Hall, London, United Kingdom.

- 20.Kool, M., J. W. Voncken, F. L. van Lier, J. Tramper, and J. M. Vlak. 1991. Detection and analysis of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus mutants with defective interfering properties. Virology 183:739-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kool, M., P. M. van den Berg, J. Tramper, R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1993. Location of two putative origins of DNA replication of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 192:94-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kool, M., J. T. Voeten, R. W. Goldbach, J. Tramper, and J. M. Vlak. 1993. Identification of seven putative origins of Autographa californica multiple nucleocapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus DNA replication. J. Gen. Virol. 74:2661-2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kool, M., R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1994. A putative non-hr origin of DNA replication in the HindIII-K fragment of Autographa californica multiple nucleocapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 75:3345-3352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kool, M., C. H. Ahrens, J. M. Vlak, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1995. Replication of baculovirus DNA. J. Gen. Virol. 76:2103-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krell, P. J. 1996. Passage effect of virus infection in insect cells. Cytotechnology 20:125-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, H. Y., and P. J. Krell. 1992. Generation and analysis of defective genomes of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 66:4339-4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, H., and P. J. Krell. 1994. Reiterated DNA fragments in defective genomes of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus are competent for AcMNPV-dependent DNA replication. Virology 202:418-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leisy, D. J., and G. F. Rohrmann. 1993. Characterization of the replication of plasmids containing hr sequences in baculovirus-infected Spodoptera frugiperda cells. Virology 196:722-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luckow, V. A., and M. D. Summers. 1988. Trends in the development of baculovirus expression vectors. Biotechnology 6:47-55. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luckow, V. A., S. C. Lee, G. F. Barry, and P. O. Olins. 1993. Efficient generation of infectious recombinant baculoviruses by site-specific transposon-mediated insertion of foreign genes into a baculovirus genome propagated in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 67:4566-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luque, T., R. Finch, N. Crook, D. R. O'Reilly, and D. Winstanley. 2001. The complete sequence of the Cydia pomonella granulovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 10:2531-2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merrihew, R. V., W. C. Clay, J. P. Condreay, S. M. Witherspoon, W. S. Dallas, and T. A. Kost. 2001. Chromosomal integration of transduced recombinant baculovirus DNA in mammalian cells. J. Virol. 75:903-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muñoz, D., J. I. Castillejo, and P. Caballero. 1998. Naturally occurring deletion mutants are parasitic genotypes in a wild-type nucleopolyhedrovirus population of Spodoptera exigua. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4372-4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muyrers, J. P., Y. Zhang, G. Testa, and A. F. Stewart. 1999. Rapid modification of bacterial artificial chromosomes by ET-recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:1555-1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oppenheimer, D. I., and L. E. Volkman. 1997. Evidence for rolling circle replication of Autographa californica M nucleopolyhedrovirus genomic DNA. Arch. Virol. 142:2107-2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Reilly, D. R., L. K. Miller, and V. A. Luckow. 1992. Baculovirus expression vectors: a laboratory manual. W. H. Freeman, New York, N.Y.

- 37.Pearson, M., R. Bjornson, G. Pearson, and G. Rohrmann. 1992. The Autographa californica baculovirus genome: evidence for multiple replication origins. Science 57:1382-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearson, M. N., R. M. Bjornson, C. Ahrens, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1993. Identification and characterization of a putative origin of DNA replication in the genome of a baculovirus pathogenic for Orgyia pseudotsugata. Virology 197:715-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pijlman, G. P., E. van den Born, D. E. Martens, and J. M. Vlak. 2001. Autographa californica baculoviruses with large genomic deletions are rapidly generated in infected insect cells. Virology 283:132-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Shizuya, H., B. Birren, U. J. Kim, V. Mancino, T. Slepak, Y. Tachiiri, and M. Simon. 1992. Cloning and stable maintenance of 300-kilobase-pair fragments of human DNA in Escherichia coli using an F-factor-based vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8794-8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slavicek, J. M., M. J. Mercer, M. E. Kelly, and N. Hayes Plazolles. 1996. Isolation of a baculovirus variant that exhibits enhanced polyhedra production stability during serial passage in cell culture. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 67:153-160. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smits, P. H., and J. M. Vlak. 1988. Biological activity of Spodoptera exigua nuclear polyhedrosis virus against S. exigua larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 51:107-114. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Summers, M. D., and G. E. Smith. 1987. A manual of methods for baculovirus vectors and insect cell culture procedures. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station bulletin no. 1555. Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, College Station.

- 45.van Loo, N. D., E. Fortunati, E. Ehlert, M. Rabelink, F. Grosveld, and B. J. Scholte. 2001. Baculovirus infection of nondividing mammalian cells: mechanisms of entry and nuclear transport of capsids. J. Virol. 75:961-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Strien, E. A., D. Zuidema, R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 1992. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the polyhedrin gene of Spodoptera exigua nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2813-2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vlak, J. M. 1979. The proteins of nonoccluded Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus produced in an established cell line of Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 34:110-118. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, K., C. Boysen, H. Shizuya, M. I. Simon, and L. Hood. 1997. Complete nucleotide sequence of two generations of a bacterial artificial chromosome cloning vector. BioTechniques 23:992-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, Y., and E. B. Carstens. 1996. Initiation of baculovirus DNA replication: early promoter regions can function as infection-dependent replicating sequences in a plasmid-based replication assay. J. Virol. 70:6967-6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, Y., G. Liu, and E. B. Carstens. 1999. Replication, integration, and packaging of plasmid DNA following cotransfection with baculovirus viral DNA. J. Virol. 73:5473-5480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]