Abstract

Biologically important joining of RNA pieces in cells, as exemplified by splicing and some classes of RNA editing, is posttranscriptional, whereas in RNA viruses it is generally believed to occur during viral RNA polymerase-dependent RNA synthesis. Here, we demonstrate the assembly of precise genome of an RNA virus (poliovirus) from its cotransfected fragments, which does not require specific RNA sequences, takes place before generation of the viral RNA polymerase, and occurs in different ways: Apparently unrestricted ligation of the terminal nucleotides, joining of any one of the two entire fragments with the relevant internal nucleotide of its partner, or internal crossovers within the overlapping sequence. Incorporation of the entire 5′ or 3′ partners into the recombinant RNA is activated by the presence of terminal 3′-phosphate and 5′-OH, respectively. Such postreplicative reactions, fundamentally differing from the known site-specific and structurally demanding cellular RNA rearrangements, might contribute to the origin and evolution of RNA viruses and could generate new RNA species during all stages of biological evolution.

Keywords: Evolution, poliovirus, RNA ligation, RNA recombination

INTRODUCTION

A variety of important biological processes involve covalent rearrangements of RNA molecules, such as joining of noncontiguous segments of the same RNA molecule or of segments of different RNA species. Two fundamentally distinct mechanisms, nonreplicative (posttranscriptional) and replicative/transcriptional, are used to accomplish this goal. The former operates with cellular RNAs and is exemplified by various types of splicing (Gonzalez et al. 1999; Reed 2000; Doudna and Cech 2002; Singh 2002) and insertion/deletion RNA editing (Simpson et al. 2003). Common features of these processes are their site specificity and strict structural requirements, regardless of whether they are accomplished by enzymatic or ribozyme mechanisms.

Assembly of RNA molecules from noncontiguous or completely separated parts is a fundamental property of many, if not all, RNA viruses as well. It underlies such diverse processes as recombination (Lai 1992; Nagy and Simon 1997; Worobey and Holmes 1999), discontinuous transcription in nidoviruses, for example, coronaviruses (Lai and Holmes 2001), and acquisition of capped 5′-segments of host mRNA by transcripts of several families of viruses with negative-strand RNA genomes, for example, influenza virus (Lamb and Krug 2001). All of these processes, distinctive from the rearrangements of cellular RNAs, are believed to occur during the viral RNA polymerase-dependent RNA synthesis. Another distinction of viral RNA rearrangements, at least as far as RNA recombination in many viruses is concerned, is much more relaxed structural requirements.

Recently, it has been shown that biologically active molecules can also be produced by relatively site-unspecific nonhomologous nonreplicative RNA recombination. In one study (Chetverin et al. 1997), overlapping 5′- and 3′-fragments were prepared from the small RNA species that, when intact, were replicable by the Qβ phage replicase. In a cell-free system containing Qβ replicase and rNTPs, these fragments were converted into species replicable by the phage enzyme as a result of nonhomologous recombination, which was dependent on the presence of the 3′-OH group on the 5′-fragment. Those authors suggested that the recombination was accomplished by a splicing-like reaction guided by a secondary structure. Nonhomologous nonreplicative RNA recombination was also reported to occur in poliovirus (Gmyl et al. 1999). Again, overlapping pairs of fragments of viral RNA were used, one of which represented a nearly full-length 5′-untranslated region (5UTR) of the viral genome with all its replicative and translational cis-acting elements intact but lacking the polyprotein-coding frame and 3UTR. The missing RNA parts were present in the other fragment, which however carried 5UTR mutations and deletions inactivating its replicative and/or translational template activities. Upon cotransfection, these fragments generated infectious progeny containing nonhomologous recombinant genomes with the 5UTR markedly modified with respect to both the length and sequence. In a subset of these recombinants, the entire 5′-fragment was incorporated into the genome, provided this fragment had the 3′-teminal phosphate group.

The above findings raised the possibility that RNA molecules are intrinsically able to covalently interact with each other in a much less restricted manner than is currently accepted. Obviously, if this notion is correct, it would have profound biological implications. However, one could argue that more rigorous evidence is needed to accept this unorthodox view. Indeed, the splicing-like nonhomologous recombination described by Chetverin et al. (1997) appeared to require the presence of Qβ replicase, although the enzyme-independent but much less efficient recombination could also be observed (Chetverina et al. 1999). In the case of poliovirus recombination studied by Gmyl et al. (1999), there was a possibility, though seemingly unlikely, that a very low level of translation of apparently untranslatable 3′-fragments of the viral RNA could have occurred and that the trace amounts of the viral RNA polymerase thus formed could have generated the recombinants by the canonical replicative template switch mode.

The goal of the present study was to unequivocally ascertain whether joining of fragments of poliovirus RNA could indeed occur without participation of the viral RNA polymerase and, if so, to define relevant requirements. To this end, we prepared new pairs of fragments of the viral genome, this time with interruptions within the sequence encoding protein 3Dpol, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Therefore, joining of the fragments was an absolute prerequisite for the appearance of this enzyme. The validity of such an experimental design fully depended on the feasibility of previously unreported precise (homologous) nonreplicative crossovers at arbitrarily selected sites. Clearly, the precision was needed to preserve the polymerase reading frame. The experiments reported here proved that precise nonreplicative recombination does occur. Moreover, the results suggest that, unexpectedly, RNA molecules are able to covalently join each other in several apparently promiscuous ways.

RESULTS

Ligation reaction and its requirements

Mechanistically, nonreplicative RNA recombination may be regarded as ligation of RNA species generated prior to or in concert with the ligation step. Therefore the possibility of ligation of the viral RNA genome with a single nick within the sequence encoding the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase was studied first. Three pairs of recombination partners differing in the position of the missing phosphodiester bond and the potential to generate heteroduplexes were designed (Fig. 1 ▶). The introduced interruptions separated some 200–250 (depending on the construct) N-terminal amino acid residues of the 3Dpol RNA polymerase from the remaining part of the enzyme containing the putative RNA binding domain and the catalytic center (Hansen et al. 1997; Cameron et al. 2002). The shorter N-terminal portion of the RNA polymerase could be expressed from the IRES-harboring 5′-terminal RNA partner, whereas the bulk of the enzyme-coding sequence resided within the 3′-terminal partner, which could not be translated because of the lack of appropriate cis-signals.

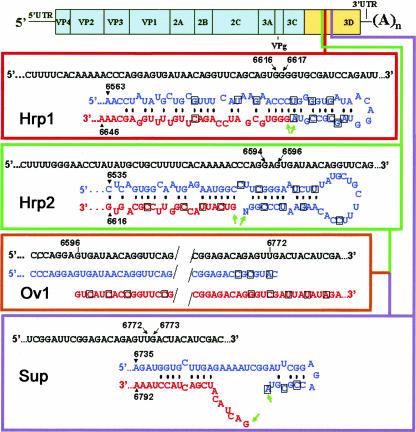

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the recombination partners. The viral RNA is composed of the 5UTR, polyprotein reading frame, 3UTR, and poly(A). The sequence encoding viral RNA polymerase (3D) is in yellow. The wild-type nucleotide sequences corresponding to the junction between the terminal sequences of the recombination partners are shown as upper lines in each rectangle, with the coordinates of the partners’ termini indicated. Terminal sequences of the 5′- and 3′-segments are in blue and red, respectively, with engineered silent mutations boxed. The 3′-terminal N of Hrp2 corresponds to the nucleotide, A or C, ligated to the original transcript. The 5′- and 3′-Ov1 partners correspond to the 5′ Sup and 3′ Hrp2 partners (with additional silent mutations), respectively. The green arrows mark the to-be-ligated nucleotides. Possible heteroduplex structures between the partners in Hrp1 and Hrp2 pairs are shown. There are no stable heteroduplexes in the case of Sup or Ov1 pairs (although some potential pairing is shown for the former case).

Previous results with imprecise RNA recombination (Gmyl et al. 1999) suggested that ligation of the 5′- and 3′- partners might depend on the structure of their terminal nucleotides. Therefore, most of the partners were prepared in either of the two forms, the 5′- partner containing a phosphorylated (P) or nonphosphorylated (NP) 3′-nucleotide and the 3′-partner harboring a 5′-OH (O) or 5′-triphosphate (3P) group.

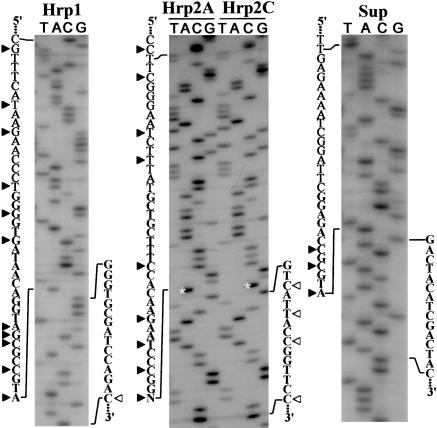

The Hrp1 pair (Fig. 1 ▶) was engineered to mimic hypothetical hairpin-like intermediates postulated to be involved in the imprecise recombination within the poliovirus 5UTR (Gmyl et al. 1999). The Hrp1 fragments had the potential to form a heteroduplex, in which the to-be-joined nucleotides would lie in close proximity to one another within a helical element. This was achieved by introducing, into both partners, silent mutations, serving also as genetic markers. In the context of the whole genome, these mutations did not impair the virus viability (data not shown). The Hrp1 pair of 5′-partner and O 3′-partner generated, upon cotransfection, viable progeny in the range of 100–200 plaque-forming units (p.f.u.) per sample containing 1 μg of each partner (Table 1 ▶). The rescued genomes were represented by precise recombinants having no mutations in the crossover region but retaining all of the genetic markers of each fragment (Fig. 2 ▶). This was true of the RNA prepared from plaques or isolated from purified virus after two passages on RD cells (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Efficiency of generation of viable viral clones depending on forms of terminal nucleotides in ligated fragments

| Forms of 3′-partner | |||

| Exp. no. | Forms of 5′-partner | 3Pa | Oa |

| 1 | Hrp1, Pb | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 156 ± 27 |

| Sup, Pb | 0 | 114 ± 30 | |

| 2 | Sup, Pb | nd | 177 ± 33 |

| Sup, NPc | nd | 8.3 ± 3.6 | |

| 3 | Hrp2A Pd | 0 | 66 ± 14 |

| Hrp2A cPe | 0 | 83 ± 14 | |

| 4 | Hrp2C Pd | nd | 110 ± 45 |

| Hrp2C cPe | nd | 85 ± 32 | |

aThe average numbers of plaques per flask ± standard deviations on day 3 after transfection are given. nd, not done.

bThe P forms were prepared by oxidation/β-elimination.

cThe NP form of Sup was prepared by phosphatase treatment of the P form.

dThe P forms were prepared by ligation with pAp (Hrp2A) or pCp (Hrp2C), respectively.

eThe cyclic 2′,3′-phosphate (cP) forms of the Hrp2 5′-partner were prepared by the RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase treatment of respective P forms.

FIGURE 2.

Ligation of fragments of the viral RNA. Examples of sequences at the crossover sites of the ligation products of different pairs of RNA fragments. For the Hrp2 pair, the results with the variants 3′-terminated with A (Hrp2A) and C (Hrp2C) are shown. The 5′- and 3′-terminal sequences of the respective ligation partners are given at the left and right sides of each sequencing gel, respectively. The silent mutations serving as genetic markers of the 5′- and 3′-partners are shown as solid and empty arrowheads, respectively. The bands corresponding to different 3′-terminal nucleotides of the Hrp2A and Hrp2C 5′-fragments are marked with asterisks.

The Hrp2 pair of RNAs (Fig. 1 ▶) had the interruption within the 3Dpol sequence ~20 nt upstream of that in Hrp1. They retained the potential to form a heteroduplex, but the helical element thus formed should have a flexible hinge, and therefore the to-be-joined nucleotides were not forced to lie as closely as was the case with Hrp1. In addition, the original Hrp2 5′-fragment lacked the 3′-terminal nucleotide, which was added by T4 RNA ligase before the transfection (see Materials and Methods). This was done to ascertain whether the efficiency of ligation depended on the specificity of the interacting nucleotides and on the importance of base-pairing of the 3′-terminal nucleotide (which was realized in the case of added A-residue but not C-residue; see Fig. 1 ▶). As shown in Table 1 ▶, ligation of P and O forms of the Hrp2 fragments occurred with efficiency comparable to that of Hrp1 despite the lack of the enforced neighborhood of the to-be-ligated nucleotides and regardless of whether the 3′-terminal nucleotide of the 5′-fragment was represented by A or C residues. The products of ligation were represented by precise recombinants (Fig. 2 ▶).

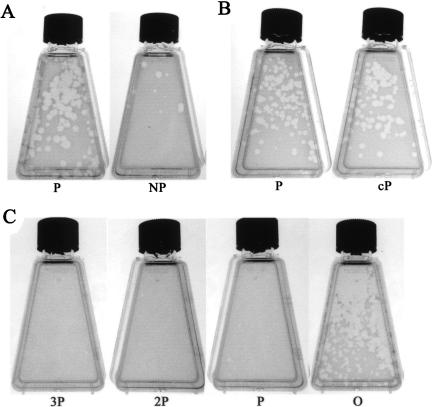

The Sup pair (Fig. 1 ▶) lacked a phosphodiester bond some 150 nt downstream of the nick in Hrp1 and had even less stringent (compared to Hrp2) constraints with regards to the mutual orientation of the terminal nucleotides. The fragments had no potential to form stable heteroduplexes in the vicinity of the ligation sites. Despite this, efficient ligation did occur (Table 1 ▶). Again, the expected markers were in place in the sequenced recombinants (Fig. 2 ▶). The use of NP 5′-partner or 3′-partner resulted in a dramatically lower, if any, yield of viable recombinants (Fig. 3A ▶; Table 1 ▶). Combinations other than P and O failed to be efficiently ligated in the case of the Hrp1 or Hrp2 pair of partners as well (data not shown). Not only triphosphorylated (3P) but also diphosphorylated (2P) and monophosphorylated (P) forms of the 5′-terminal nucleotide of the 3′-partner also failed to efficiently generate recombinants upon cotransfection with the P form of the 5′-partners (Fig. 3C ▶).

FIGURE 3.

Plaque formation by the ligation products of the genomic segments with different terminal structures. (A) Ligation of the P and NP forms of the Sup 5′-partner with the O form of its counterpart. (B) Ligation of the P and cP forms of the Hrp2C 5′-partner with the O form of its counterpart. (C) Ligation of the P form of the Sup 5′-partner with the O, P, 2P, and 3P forms of its counterpart. The plaques were photographed on the third day after transfection.

The above results demonstrated that two RNA molecules could be efficiently ligated in the transfected cell, provided the 5′- and 3′-partners were in 3′-phosphate and 5′-OH forms, respectively. Such a combination could hardly be considered a good substrate for a ligase, and activation of one or the other partners seemed quite likely. In light of the finding that, in RNA ligation reactions, an acceptable partner of the 5′-OH group could be a 3′-terminal cyclic 2′,3′-phosphate (Abelson et al. 1998; Reid and Lazinski 2000; Salgia et al. 2003), we tested the effect of cyclization of the 3′-terminal nucleotide of the Hrp2 5′-partner on the efficiency of its ligation with the 3′-partner. The cyclization was achieved by the treatment with the RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase (Filipowicz et al. 1983; Genschik et al. 1997). The ability of the enzyme to efficiently convert the terminal 3′-phosphate of a large molecule of the Hrp2 5′-fragment was checked and confirmed (data not shown). This conversion, however, did not result in any detectable activation of the ligation reaction (Fig. 3B ▶; Table 1 ▶).

Recombination between overlapping fragments

In the above cases, the end-to-end ligation of RNA fragments was studied. The existence of pieces of a viral genome precisely supplementing each other under natural conditions, though possible, seems relatively unlikely. To better approach natural conditions and in fact to study true recombination rather than ligation, we investigated a fourth pair of partners, Ov1, composed of the Sup 5′-partner and the Hrp2 3′-partner with six additional silent mutations (Fig. 1 ▶). The 3′- and 5′-terminal sequences of the two partners overlapped each other by 177–178 nt in the case of P and NP 5′-partners, respectively (because the P partner was one nucleotide shorter due to β-elimination of the 3′-terminal nucleotide of the NP partner). Because in designing these partners no special attempt was made to facilitate heteroduplex formation or introduce other structural constraints, the partners could be regarded as a randomly cleaved viral genome. Nevertheless, the Ov1 partners reproducibly generated viable progeny (Table 2 ▶).

TABLE 2.

Dependence of crossover location on the forms of Ov1 terminal nucleotides

| Number of sequenced recombinants | ||||||

| Forms of | ||||||

| 5′-partner | 3′-partner | Number of p.f.u. | Total | With entire 5′-partner | With entire 3′-partner | With internal crossovers |

| NP | 3P | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| NP | O | 8.8 ± 2.7 | 10 | 0 | 8 | 2 |

| P | 3P | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 3 |

| P | O | 9.0 ± 2.0 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

The NP form corresponded to the original transcript. P form was prepared by the oxidation/β-elimination of the NP, and O form was prepared by phosphatase treatment. The average numbers of plaques per flask on day 3 posttransfection are given ± standard deviations.

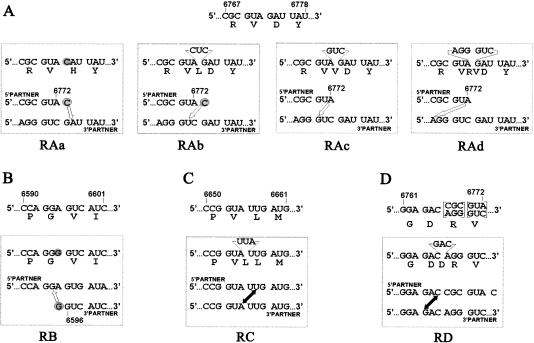

Importantly, the position of the crossovers depended on the form in which the partners were used (Fig. 4 ▶; Table 2 ▶). With the NP 5′-partner and 3′-partner, all of the sequenced crossover sites were within the overlapping part of the RNA fragments; that is, they were internal. Their exact positions remained unknown because of the lack of appropriate internal markers (see below for exceptions). The majority of recombinants between the 5′-partner and 3′-partner acquired the whole 5′-partner, a phenomenon previously described for nonhomologous RNA recombination (Gmyl et al. 1999). In contrast, in the recombinants generated when the respective termini of both partners lacked free phosphate groups, incorporation of the entire 3′-partner was most often found (the intervention of the whole 3′-partner into an internal position of the viral RNA has not been previously documented). Thus, the terminal nucleotides of the 5′-partner or O 3′-partner demonstrated the capacity to interact with the proper internal nucleotides of their counterparts. With a combination of the 5′-partner and O 3′-partner, the majority of recombinants acquired either the whole 5′-partner or the whole 3′-partner, but some had internal crossovers.

FIGURE 4.

Three types of genomes generated by recombination between Ov1 partners. Terminal sequences of the partners are shown on the left side of the panel. The 3′-terminal C-residue of the 5′-partner, which was removed during preparation of its P form, is shown in parentheses. The genetic markers of the 5′- and 3′-partners are shown as solid and empty arrowheads, respectively. Portions of the sequencing gels corresponding to the termini of the partners are shown. Arrows indicate the direction of electrophoresis. Examples of recombinants obtained upon crossing NP and 3P (internal crossover), NP and O (entire 3′-partner), and P and 3P (entire 5′-partner) forms are given.

The overwhelming majority of progeny generated by the Ov1 partners were represented by precise (homologous) recombinants (Fig. 4 ▶). However, there were several interesting exceptions. The acquisition of the entire 5′-partner in the Ov1 recombination was sometimes accompanied by alterations in the crossover site consisting of a point mutation or insertion of one or two codons (Fig. 5A ▶). These alterations could be readily explained as follows. The 5′-partner might acquire, during the run-off transcription by T7 RNA polymerase, a 3′-terminal nontemplated nucleotide (Milligan et al. 1987; Gmyl et al. 1999). In this case, C6773 (normally removed by the oxidation/β-elimination reaction; see Materials and Methods) would be converted (by the same reaction) into a P-form terminal nucleotide (encircled in Fig. 5A ▶), and a quasi-precise recombination would involve C6773 and A6774 rather than A6772 and G6773 as in the “correct”, precise instance. As a result, a GAU (Asp) codon in recombinant RAa was replaced by a CAU (His) codon. In addition, either the correct A6772 or nonremoved C6773 terminal nucleotides of the 5′-partner could react with a nucleotide located three (recombinants RAb and RAc) or six positions (RAd) upstream of the “correct” one, resulting in insertion of one or two additional codons (Fig. 5A ▶). One altered crossover site was also encountered in the case of incorporation of the entire Ov1 3′-partner (Fig. 5B ▶). It could likely be explained by acquisition of an additional G residue at the 5′-terminus of the 3′-partner during T7 RNA polymerase transcription (Pleiss et al. 1998). In this case, the quasi-precise recombination would mean interaction between the additional 5′-terminal G of the 3′-partner (circled in Fig. 5B ▶) and G6594 of the 5′-partner, resulting in the replacement of a GGA (Gly) codon by its synonym GGG. Aberrant crossovers, inserting an additional codon, were also observed upon internal recombination between Ov1 partners (Fig. 5C,D ▶). These coding changes were not detrimental to the virus viability in view of a relative variability of this part of the picornavirus 3Dpol protein. These examples showed that the location of crossovers could be shifted, at least to some extent.

FIGURE 5.

Aberrant recombination between Ov1 partners involving incorporation of the entire 5′-partner (A), or 3′-partner (B), or internal crossovers (C,D). The expected (and actually most often found) nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the crossover regions of the relevant precise recombinants are shown above the rectangles. Amino acids are given in the single-letter code. Because the parts of the overlapping regions in the 5′- and 3′-partners shown in panel D are different due to the presence of silent marker mutations, the bracketed codons in the precise recombinant might be represented by two synonymous versions. The determined aberrant sequences are given in the upper parts of the rectangles. Nucleotides corresponding to the point mutations in recombinants RAa and RB are shadowed; insertions of three or six nucleotides in all other recombinants are indicated. Proposed mechanisms underlying generation of the aberrant recombinants are given in the lower parts of the rectangles. The additional terminal nucleotides presumably added by T7 polymerase to the 5′-partner (RAa and RAb) and 3′-partner (RB) are encircled. Open arrows connect a terminal nucleotide of the 5′-partner or 3′-partner with an internal nucleotide of their counterparts; double-headed solid arrows connect the ligated nucleotides in internal crossovers.

“Monstrous” recombinants

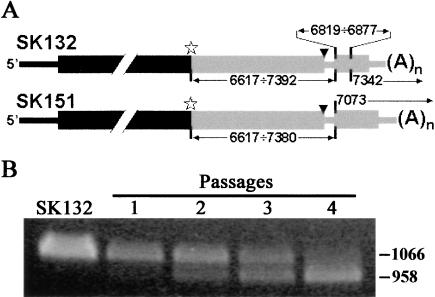

Most likely, the precision (or quasi-precision) of the recombinant genomes was due to the selection for virus viability. However, imprecise (nonhomologous) recombinants could also be observed when their altered genome structure was compatible with viability (Gmyl et al. 1999). In this study, in addition to aberrant recombinants RAb, RAc, RAd, RC, and RD (Fig 5 ▶), two imprecise “monstrous” viable recombinants were detected in separate experiments involving a partially degraded preparation of the Hrp1 3′-partner and an intact Hrp1 5′-partner (Fig. 6A ▶). The recombinants had a correct ligation site between nt 6616 and 6617 and the intact polyprotein reading frame but harbored additional “appendages” fused to distinct nucleotides within the 3UTR. These appendages corresponded to contiguous (SK151) or noncontiguous (SK132) portions of a 3′-terminal 3Dpol-coding sequence, 3UTR and a poly(A) tail. These “monsters” appeared to be generated by multiple recombination events, consistent with the existence of multiple sites for nonreplicative RNA recombination.

FIGURE 6.

“Monstrous” recombinant genomes. (A) Schematic structures of the recombinant RNAs obtained in separate experiments involving the Hrp1 pair, in which a partially degraded 3′-partner was used. Portions originating from the 5′- and 3′-partners are shown in black and gray, respectively, with coordinates of the segments derived from the 3′-partner indicated. The stars mark the correct fusion between positions 6616 and 6617. The arrowheads denote the terminal codon of the polyprotein frame. Segments corresponding to the untranslated regions are shown thinner than the coding regions. (B) Instability of the SK132 genome. The PCR products obtained by using primers corresponding to positions 6496–6515 (sense) and 5′ (T)15CTCC 3′ (antisense) of the Hrp1 RNA from the newly generated SK132 genome and from the viral RNA harvested from its four consecutive passages in Vero cells. Sequencing of the 958-nt-long and 1066-nt-long products revealed the structures corresponding to the original Hrp1 and the monster shown in panel A, respectively.

The monsters appeared to be genetically unstable, and their RNAs were converted into the canonical form (they lost the erroneously acquired parts) upon a few virus passages (Fig. 6B ▶).

DISCUSSION

The results reported here definitely demonstrate the ability of fragments of viral RNA to recombine in a nonreplicative mode, that is, without participation of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. The possibility that the recombinants were generated by DNA- rather than RNA-recombination can be ruled out, for the following reasons. (1) The transcripts were purified by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. (2) The procedures used for modifications of the terminal nucleotides and shown to significantly change the yield and structure of recombinants were not expected to affect the putative recombinogenic properties of DNA. (3) Even when used in concentrations exceeding possible DNA admixture to the transcript preparations, circular or linearized DNA templates did not produce viral progeny in transfected cells (data not shown). (4) Treatment of the transcripts with an RNase-free DNase did not influence the yield of recombinants, whereas the treatment with a DNase-free RNase prevented the generation of viable recombinants (data not shown).

It is known that some host DNA-dependent RNA polymerases are capable of template switching (Nudler et al. 1996; Izban et al. 1998; Kandel and Nudler 2002) and of copying certain RNA molecules possessing recognizable promoter-like elements, for example viroids (Diener 2001) or hepatitis delta virus (Modahl et al. 2000). Also, cellular RNA-dependent RNA polymerases implicated in gene silencing (Nishikura 2001) appear to be present in different organisms, and the tomato enzyme was characterized in some detail (Schiebel et al. 1993, 1998). The plant RNA-dependent RNA polymerases were shown to be able to copy single-stranded RNA templates but generated heterogeneous and relatively short products (Ikegami and Fraenkel-Conrat 1979; Schiebel et al. 1993). Even more importantly, no homologs of these enzymes have been found in mammalian cells. In sum, none of the cellular RNA polymerases, either DNA- or RNA-dependent, have ever been demonstrated to replicate long linear viral RNA species, such as the poliovirus genome. Again, the observed impact of terminal structure modification on the incorporation of RNA fragments into a recombinant molecule is hardly compatible with the involvement of an RNA polymerase in this process. All these considerations leave a nonreplicative mechanism as the only feasible explanation for the phenomena described here.

Replicative and nonreplicative recombination in RNA viruses

RNA recombination, first discovered in poliovirus (Ledinko 1963; reviewed in Agol 1997), is now described in many virus groups (Lai 1992; Nagy and Simon 1997; Worobey and Holmes 1999). Recombination is generally believed to occur by a replicative template switch (copy-choice) mode, whereby an RNA molecule initiated by the viral RNA polymerase on one viral RNA template is finished by copying another viral RNA template (Cooper 1977; Kirkegaard and Baltimore 1986; Romanova et al. 1986; Arnold and Cameron 1999; Nagy et al. 1999; Dzianott et al. 2001; Kim and Kao 2001). Similar mechanisms are thought to underlie other covalent viral RNA rearrangements, such as deletions and insertions (duplications). Various models for these replicative recombination/rearrangements have been proposed (Kuge et al. 1986; Romanova et al. 1986; Jarvis and Kirkegaard 1991; Pilipenko et al. 1995; Nagy and Simon 1997), but the exact mechanisms are yet to be elucidated.

The present and previous (Gmyl et al. 1999) studies unambiguously demonstrate the existence of an additional, nonreplicative mechanism(s) able to generate both imprecise and precise viable recombinants of an RNA virus. One may argue that the observed recombination takes place in the cells that receive a very large number of viral RNA fragments. This number however appears to be comparable to that synthesized during poliovirus infection, that is, on the order of 105 viral genomes per cell. Our results raise questions about the nature of the mechanisms, replicative or nonreplicative, responsible for various known recombination events. It was argued that homologous RNA recombination should perhaps more likely be accomplished by the template switch mode, because it was not easy to envision a nonreplicative mechanism ensuring precision of the crossovers (Chetverin 1999). Although the putative mechanism remains elusive indeed (see below), the results presented here demonstrate that precise (homologous) nonreplicative recombination can occur and, at least under certain conditions, can occur quite efficiently. It should be admitted however that the quantitative contribution of the nonreplicative rearrangements to the natural and laboratory evolution of viral RNAs is yet to be established.

Does precision reflect promiscuity?

Efficient end-to-end ligation of complementing fragments of the viral genome suggests that terminal nucleotides of the fragments may encounter each other with a relatively high probability, at least under the conditions when a large RNA pool is transfected into a cell. The potential to form a heteroduplex in which the to-be-ligated nucleotides would lie in close proximity seems not essential. It could be imagined that termini of some molecules are hidden inside complex secondary or tertiary structures but the transfected molecules are perhaps moving one relative to another so efficiently that, as a rule, contacts between arbitrarily chosen nucleotides in separate molecules become feasible during relatively short periods of time, for example, hours. The ligation products are precise recombinants simply because the fragments are designed to achieve such a goal.

Generation of precise recombinants by overlapping fragments of viral RNA is much more surprising. It is shown here that the precise nonreplicative crossovers can occur at different locations and might involve different nucleotides. In principle, the precision may result from three fundamentally different, but not necessarily mutually exclusive, mechanisms.

It may be speculated that the overlapping parts are somehow aligned, severely restricting thereby the repertoire of nucleotides able to interact with each other. There is no evidence that such alignment may actually occur, although a somewhat similar idea—for example, formation of heteroduplexes involving short inverted repeats present in any RNA molecule—has been considered as a factor contributing to the choice of crossover sites during replicative recombination (Romanova et al. 1986; Tolskaya et al. 1987; Nagy and Bujarski 1993; Figlerowicz 2000).

Another way to obtain precise recombinants is to allow (nearly) promiscuous covalent interactions between any nucleotides, internal or terminal, in the pool of viral fragments, followed by selection of viable, that is precise or nearly so, genomes. Such mechanisms are expected to generate recombinants with enormous numbers of different crossover sites, especially if intramolecular reactions are also taken into account. The promiscuity is consistent with the fact that nonreplicative recombination may be only nearly precise or completely imprecise (nonhomologous; see also Gmyl et al. 1999).

Precise internal recombination may result from a limited number of “hot” cleavable sites generating readily ligatable termini (see below). In this case, the selection for viability would involve a much more limited number of potentially possible recombinants.

Unfortunately, a direct RT-PCR assay for recombinant molecules could hardly permit reliable identification of primary recombinants, due to the well known template-switching ability of reverse transcriptases. Thus, the existing data do not permit choosing among the above possibilities. However, any of these possibilities would involve some unknown, or at least underappreciated, properties of RNA molecules.

Unsolved mechanism(s) of nonreplicative RNA recombination

Terminal 3′-phosphate and 5′-OH groups, without activation, cannot serve as an appropriate substrate for known RNA ligases, regardless of their enzymatic or ribozyme nature.

Acceptable combinations are represented by 3′-terminal cyclic 2′,3′-phosphate and 5′-terminal phosphate or OH groups (Abelson et al. 1998; Reid and Lazinski 2000; Ho and Shuman 2002; Salgia et al. 2003), or by 3′-OH and 5′-phosphate groups (Cruz-Reyes et al. 2002; Simpson et al. 2003). The conversion of the 3′-terminal nucleotide of the Hrp2 5′-partner into a cyclic 2′,3′-phosphate form did not enhance the recombinogenic potential of this RNA fragment. Thus cyclization of the 3′-terminus is not either essential or limiting for the ligation reaction. It is reasonable to suggest that the ligation of fragments of the viral RNA with “unconventional” ends described here takes place intracellularly and involves some enzymes or “factors”. Their identification may be facilitated by using cell-free systems for poliovirus recombination (Duggal et al. 1997; Tang et al. 1997). Alternatively, though not very likely, the approach used here, due to its ability to detect negligible amounts of the product, may reveal some hidden intrinsic properties of RNA molecules.

Particularly puzzling are recombination events involving overlapping RNA fragments. In fact, three types of covalent joining of RNA pieces were observed in this case: intervention of either the 3′-terminal nucleotide of the 5′-fragment or the 5′-terminal nucleotide of the 3′-fragment into an internal position of their respective counterparts, as well as crossovers between internal positions of overlapping sequences. It is unknown whether each of these reactions is accomplished by a distinct mechanism or whether they exploit some common mechanism(s).

A set of hypothetical mechanisms may require prior cleavage of appropriate phosphodiester bond(s) and generation of a ligatable terminus (or termini). Such cleavages may be introduced by an endonuclease or may result from cryptic ribozyme-like activity (Gmyl et al. 1999). In both cases, these cleavages are not expected to be completely random but rather may be clustered at some hot spots (Gmyl et al. 1999). On the other hand, one may envision another set of mechanisms when breakage of a phosphodiester bond is directly coupled to the generation of another such bond (transesterification).

Because all of the 5′-partners used here contained intact 5UTR, some synthesis of viral proteins other than 3Dpol might occur in the transfected cells prior to recombination. However, none of such proteins are known to exhibit RNA-cleaving or RNA-ligating activities. Therefore, their contribution, if any, to nonreplicative RNA recombination can hardly be essential. Moreover, nonreplicative RNA recombination may occur with a comparable efficiency when genomic fragments with negligible, if any, translational template activities have been used (Gmyl et al. 1999).

Biological relevance of nonreplicative RNA recombination

The potential to shuffle domains of viral RNAs and to assemble viral genomes from RNA segments originating from different sources, including unrelated viruses or host genes, should play a pivotal role in evolution of RNA viruses (Gorbalenya 1992; Koonin and Dolja 1993). On the other hand, recombination serves the opposite, genome-stabilizing function by allowing viruses to get rid of adverse mutation inevitably generated at a high rate by the error-prone viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (Agol 2002). Both of these functions can be accomplished by either replicative or nonreplicative RNA recombination and, as mentioned above, the contribution of each is currently impossible to evaluate. Nevertheless, even if natural nonreplicative RNA recombination is a very rare event, its potential to promote horizontal transfer of genetic material between unrelated or poorly related RNA viruses as well as between host and viral RNA genomes (Monroe and Schlesinger 1983; Munishkin et al. 1988; Khatchikian et al. 1989; Charini et al. 1994; Avota et al. 1998; Baroth et al. 2000; Becher et al. 2001, 2002; Nagai et al. 2003; A.P. Gmyl, unpubl.) should not be overlooked.

It is tempting to suggest that the mechanism(s) responsible for the nonreplicative recombination between viral RNA genomes may well operate with cellular RNA species as well. In this regard, it is appropriate to note that a significant proportion of “chimeric” cellular transcripts representing noncontiguous genetic loci could be detected in the cDNA databases, and some of them could not be readily explained by canonical trans-splicing or chromosomal translocations (Romani et al. 2003). Although artifacts of different types could be responsible for the occurrence of many such chimeras (Romani et al. 2003), postreplicative joining of mRNAs or their fragments by mechanisms related to those responsible for the phenomena described here could also be a contributing factor.

Nonreplicative RNA recombination could operate during the RNA world era as well as at all subsequent stages of biological evolution. Moreover, the inherent ability of RNA molecules to recombine may also contribute, in cooperation with reverse transcription, to the evolution of cellular DNA genomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of plasmids

The Hrp1, Hrp2, and Sup 3′-partners were amplified by PCR from pT7PV1 (Pilipenko et al. 1992) carrying the full-length poliovirus genome by using one of the sense primers, 5′-ctggatcctaatacgact cactataGGGTGCGATCCAGACTTG6634-3′ (3Hrp1), 5′-ctggatccta atacgactcactataGTCATTACCGGTTCCGCAGTGGGGTGCG6623-3′ (3Hrp2), 5′-ctggatcctaatacgactcactataGACTACATCGAC6784-3′ (3Sup), and the antisense primer ER1 5′-CCTTTCGTCTTCAAGA ATTC-3′ (complementary to position 4346–4362 of pBR322). This introduced silent mutations in (underlined letters), and fused T7 promoter together with a BamHI site (lowercase letters), to the viral genome at the positions indicated. The PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI, purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, and cloned into pBR322 using BamHI and EcoRI sites. Two overlapping parts of the Ov1 3′-partner were PCR-amplified from the plasmid encoding the Hrp2 3′-partner using combinations of primers 3Hrp2 (sense)/ H1 (5′-TCTATATAATCGACCCTGTCTCCGAATCCG6754-3′; antisense) and H2 (5′-GGTCGATTATATAGACTACCTAAACCAC6796-3′; sense)/ER1. A mixture of the gel-purified products was subjected to fusion-PCR using 3Hrp2 (sense)/ER1 (antisense) primers. The resulting product was gel-purified and cloned into pBR322, as described.

To generate the 5′-partners, appropriate fragments of pT7PV1 were amplified using the sense primer B5594 (positions 5586–5606 of the poliovirus RNA) and one of the antisense primers, 5′-gaccgTACGGCGCTACCTGTTATCACCCCAGGGTTCTTATGAAACGCAGCATATAG6566-3′ (5Hrp1), 5′-catcCCGGGATTCTTGTGGAAAGCAGCATAAAGATTCCCGAAGGCCATTCTCATTGC6542-3′ (5Hrp2), 5′-gaccgTACGCGGTCTCCG6760-3′ (5Sup). The PCR products were digested with BglII, gel-purified, and introduced into the full-length viral genomes using the existing BglII site at position 5602 and an artificial SmaI site created at position 6592 by mutagenic PCR. Additionally, a genome segment between positions 7055 and 7334 was deleted from all of the 5′-partner encoding plasmids using PvuII and ScaI sites.

The primary structures of the entire 3′-partners and of the modified portions of the 5′-partners were checked by sequencing.

Preparation of transcripts and modification of terminal nucleotides

The plasmids linearized with EcoRI (all 3′-partners), SplI (Hrp1 and Sup 5′-partners), or XmaI (Hrp2 5′-partner) were transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase, purified and, when appropriate, subjected to terminal modifications: oxidation/β-elimination or pNp ligation for the preparation of 5′-partners (note that these forms were therefore one nucleotide shorter or one nucleotide longer than the original transcripts, respectively) and phosphatase treatment for the preparation of NP 5′-partners and O 3′-partners, as described (Gmyl et al. 1999). To convert the 3′-phosphate of Hrp2 5′-partners to the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate (cP) form, 5 μg of RNA was incubated in a 40-μL mixture containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ATP, 60 U of RNasin (Promega), and 1 μg of the recombinant E. coli RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase for 15 min at 25°C. The cyclase was overexpressed as His-tagged protein and purified as described (Genschik et al. 1998). To check the efficiency of cyclization, the Hrp2 5′-partners with labeled 3′-phosphate were prepared. To this end, 1 nM of the [32P]C3′p or [32P]A3′p was added to the ligation mixture during the preparation of the Hrp2 5′-partner from the original transcript. The labeled RNA, 0.5 μg, was digested with nuclease P1, and the digestion products were subjected to thin layer chromatography on PEI cellulose plate in saturated (NH4)2SO4/3M Na acetate/isopropanol (80:6:2) or 1 N acetic acid/3 M LiCl (9:1) for the cytidylic and adenylic nucleotides, respectively. Appropriate spots were cut from the plate, and their radioactivity was counted. The conversion of 3′-phosphate into cyclic form was found to be >90%. To prepare a set of Sup1 3′-partners with 5′-OH (O form), 5′-monophosphate (P), and 5′-diphosphate (2P) groups, the T7 RNA polymerase transcription was carried out in mixtures containing 2 mM each of ATP, CTP, UTP, and 0.5 mM GTP, and 5 mM of guanosine, GMP, and GDP, respectively.

Transfection

The DEAE-dextran mediated transfection of Vero cells was carried out as described (Gmyl et al. 1999) using a mixture of the 5′- and 3′-fragments (1 μg of each). Prior to transfection, the fragments were mixed in 20 μL of 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.8 and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. When indicated, 1 μL of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (1 unit, Promega) or 1 μL RNase A (20 mg/mL, Sigma) was added to the mixture.

Sequencing

The material from a plaque was suspended in 1 mL of Earle’s saline and subjected to RT-PCR using primers 5′-(T)15CTCC-3′ (antisense) and one corresponding to positions 5586–5606 (sense). The gel-purified DNA product was sequenced with a Promega fmol Sequencing Kit. Direct sequencing of RNA isolated from the purified virus was done as described (Gmyl et al. 1999).

Acknowledgments

We thank Witold Filipowicz for the plasmid encoding the bacterial RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase, and Alex Chetverin for critical reading of the first draft of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from INTAS, the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, and the Ministry of Industry, Science and Technology of the Russian Federation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5111803.

REFERENCES

- Abelson, J., Trotta, C.R., and Li, H. 1998. tRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 12685–12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agol, V.I. 1997. Recombination and other genomic rearrangements in picornaviruses. Semin. Virol. 8: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Agol, V.I. 2002. Picornavirus genetics: An overview. In The molecular biology of picornaviruses (eds. B.L. Semler and E. Wimmer), pp. 269–284. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Arnold, J.J. and Cameron, C.E. 1999. Poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3Dpol) is sufficient for template switching in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 2706–2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avota, E., Berzins, V., Grens, E., Vishnevsky, Y., Luce, R., and Biebricher, C. 1998. The natural 6 S RNA found in Qβ-infected cells is derived from host and phage RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 276: 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroth, M., Orlich, M., Thiel, H.J., and Becher, P. 2000. Insertion of cellular NEDD8 coding sequences in a pestivirus. Virology 278: 456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher, P., Orlich, M., and Thiel, H.J. 2001. RNA recombination between persisting pestivirus and a vaccine strain: Generation of cytopathogenic virus and induction of lethal disease. J. Virol. 75: 6256–6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher, P., Thiel, H.J., Collins, M., Brownlie, J., and Orlich, M. 2002. Cellular sequences in pestivirus genomes encoding γ-aminobutyric acid (A) receptor-associated protein and Golgi-associated ATPase enhancer of 16 kD. J. Virol. 76: 13069–13076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, C.E., Gohara, D.W., and Arnold, J.J. 2002. Poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3Dpol): Structure, function, and mechanism. In The molecular biology of picornaviruses (eds. B.L. Semler and E. Wimmer), pp. 255–267. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Charini, W.A., Todd, S., Gutman, G.A., and Semler, B.L. 1994. Transduction of a human RNA sequence by poliovirus. J. Virol. 68: 6547–6552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetverin, A.B. 1999. The puzzle of RNA recombination. FEBS Lett. 460: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetverin, A.B., Chetverina, H.V., Demidenko, A.A., and Ugarov, V.I. 1997. Nonhomologous RNA recombination in a cell-free system: Evidence for a transesterification mechanism guided by secondary structure. Cell 88: 503–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetverina, H.V., Demidenko, A.A., Ugarov, V.I., and Chetverin, A.B. 1999. Spontaneous rearrangements in RNA sequences. FEBS Lett. 450: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, P.D. 1977. Genetics of picornaviruses. Comp. Virol. 9: 133–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Reyes, J., Zhelonkina, A.G., Huang, C.E., and Sollner-Webb, B. 2002. Distinct functions of two RNA ligases in active Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complexes. Mol. Cell Biol. 22: 4652–4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, T.O. 2001. The viroid: Biological oddity or evolutionary fossil? Adv. Virus Res. 57: 137–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna, J.A. and Cech, T.R. 2002. The chemical repertoire of natural ribozymes. Nature 418: 222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggal, R., Cuconati, A., Gromeier, M., and Wimmer, E. 1997. Genetic recombination of poliovirus in a cell-free system. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 94: 13786–13791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzianott, A., Rauffer-Bruyere, N., and Bujarski, J.J. 2001. Studies on functional interaction between brome mosaic virus replicase proteins during RNA recombination, using combined mutants in vivo and in vitro. Virology 289: 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlerowicz, M. 2000. Role of RNA structure in nonhomologous recombination between genomic molecules of brome mosaic virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 1714–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz, W., Konarska, M., Gross, H.J., and Shatkin, A.J. 1983. RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase activity and RNA ligation in HeLa cell extract. Nucleic Acids Res. 11: 1405–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genschik, P., Billy, E., Swianiewicz, M., and Filipowicz, W. 1997. The human RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase is a member of a new family of proteins conserved in Eucarya, Bacteria and Archaea. EMBO J. 16: 2955–2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genschik, P., Drabikowski, K., and Filipowicz, W. 1998. Characterization of the Escherichia coli RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase and its σ54-regulated operon, J. Biol. Chem. 273: 25516–25526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmyl, A.P., Belousov, E.V., Maslova, S.V., Khitrina, E.V., and Agol, V.I. 1999. Nonreplicative RNA recombination in poliovirus. J. Virol. 73: 8958–8965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, T.N., Sidrauski, C., Dorfler, S., and Walter, P. 1999. Mechanism of nonspliceosomal mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response pathway. EMBO J. 18: 3119–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbalenya, A.E. 1992. Host-related sequences in RNA viral genomes. Semin. Virol. 3: 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.L., Long, A.M., and Schultz, S.C. 1997. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of poliovirus. Structure 5: 1109–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.K. and Shuman, S. 2002. Bacteriophage T4 RNA ligase 2 (gp24.1) exemplifies a family of RNA ligases found in all phylogenetic domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 12709–12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami, M. and Fraenkel-Conrat, H. 1979. Characterization of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of tobacco leaves. J. Biol. Chem. 254: 149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izban, M.G., Parsons, M.A., and Sinden, R.R. 1998. Template end-to-end transposition by RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 27009–27016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, T.C. and Kirkegaard, K. 1991. The polymerase in its labyrinth: Mechanisms and implications of RNA recombination. Trends Genet. 7: 186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel, E.S. and Nudler, E. 2002. Template switching by RNA polymerase II in vivo. Evidence and implications from a retroviral system. Mol. Cell 10: 1495–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatchikian, D., Orlich, M., and Rott, R. 1989. Increased viral pathogenicity after insertion of a 28S ribosomal RNA sequence into the haemagglutinin gene of an influenza virus. Nature 340: 156–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-J. and Kao, C. 2001. Factors regulating template switch in vitro by viral RNA-dependent RNA poloymerases: Implications for RNA–RNA recombination. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 98: 4972–4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkegaard, K. and Baltimore, D. 1986. The mechanism of RNA recombination in poliovirus. Cell 47: 433–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin, E.V. and Dolja, V.V. 1993. Evolution and taxonomy of positive-strand RNA viruses: Implications of comparative analysis of amino acid sequences. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 28: 375–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuge, S., Saito, I., and Nomoto, A. 1986. Primary structure of poliovirus defective-interfering particle genomes and possible generation mechanisms of the particles. J. Mol. Biol. 192: 473–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M.M.C. 1992. RNA recombination in animal and plant viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 56: 61–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M.M.C and Holmes, K.V. 2001. Coronaviridae: The viruses and their replication. In Fields virology, 4th ed. (eds. D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley), pp. 1163–1185. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- Lamb, R.A. and Krug, R.M. 2001. Orthomyxoviridae: The viruses and their replication. In Fields virology, 4th ed. (eds. D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley), pp. 1487–1531. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- Ledinko, N. 1963. Genetic recombination with poliovirus type 1. Studies of crosses between a normal horse serum-resistant mutant and several guanidine-resistant mutants of the same strain. Virology 20: 107–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, J.F., Groebe, D.R., Witherell, G.W., and Uhlenbeck, O.C. 1987. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res. 15: 8783–8798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modahl, L.E., Macnaughton, T.B., Zhu, N., Johnson, D.L., and Lai, M.M.C. 2000. RNA-dependent replication and transcription of hepatitis δ virus RNA involve distinct cellular RNA polymerases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 6030–6039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, S.S. and Schlesinger, S. 1983. RNAs from two independently isolated defective interfering particles of Sindbis virus contain a cellular tRNA sequence at their 5′ ends. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 80: 3279–3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munishkin, A.V., Voronin, L.A., and Chetverin, A.B. 1988. An in vivo recombinant RNA capable of autocatalytic synthesis by Q βreplicase. Nature 333: 473–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, M., Sakoda, Y., Mori, M., Hayashi, M., Kida, H., and Akashi, H. 2003. Insertion of cellular sequence and RNA recombination in the structural protein coding region of cytopathogenic bovine viral diarrhoea virus. J. Gen. Virol. 84: 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, P.D. and Bujarski, J.J. 1993. Targeting the site of RNA–RNA recombination in brome mosaic virus with antisense sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90: 6390–6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, P.D. and Simon, A.E. 1997. New insights into the mechanisms of RNA recombination. Virology 235: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, P.D., Pogany, J., and Simon, A.E. 1999. RNA elements required for RNA recombination function as replication enhancers in vitro and in vivo in a plus-strand RNA virus. EMBO J. 18: 5653–5665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikura, K. 2001. A short primer on RNAi: RNA-directed RNA polymerase acts as a key catalyst. Cell 107: 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudler, E., Avetissova, E., Markovtsov, V., and Goldfarb, A. 1996. Transcription processivity: Protein-DNA interactions holding together the elongation complex. Science 273: 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilipenko, E.V., Gmyl, A.P., Maslova, S.V., Svitkin, Y.V., Sinyakov, A.N., and Agol, V.I. 1992. A prokaryotic-like cis-element in the cap-independent internal initiation of translation on picornavirus RNA. Cell 68: 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilipenko, E.V., Gmyl, A.P., and Agol, V.I. 1995. A model for rearrangements in RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 23: 1870–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleiss, J.A., Derrick, M.L., and Uhlenbeck, O.C. 1998. T7 RNA polymerase produces 5′ end heterogeneity during in vitro transcription from certain templates. RNA 4: 1313–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, R. 2000. Mechanisms of fidelity in pre-mRNA splicing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12: 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid, C.E. and Lazinski, D.W. 2000. A host-specific function is required for ligation of a wide variety of ribozyme-processed RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 424–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani, A., Guerra, E., Trerotola, M., and Alberti, S. 2003. Detection and analysis of spliced chimeric mRNAs in sequence databanks. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanova, L.I., Blinov, V.M., Tolskaya, E.A., Viktorova, E.G., Kolesnikova, M.S., Guseva, E.A., and Agol, V.I. 1986. The primary structure of crossover regions of intertypic poliovirus recombinants: A model of recombination between RNA genomes. Virology 155: 202–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgia, S.R., Singh, S.K., Gurha, P., and Gupta, R. 2003. Two reactions of Haloferax volcanii RNA splicing enzymes: Joining of exons and circularization of introns. RNA 9: 319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiebel, W., Haas, B., Marinkovic, S., Klanner, A., and Sänger, H.L. 1993. RNA-directed RNA polymerase from tomato leaves. II. Catalytic in vitro properties. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 11858–11867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiebel, W., Pélissier, T., Riedel, L., Thalmeir, S., Schiebel, R., Kempe, D., Lottspeich, F., Sänger, H.L., and Wassenegger, M. 1998. Isolation of an RNA-directed RNA polymerase-specific cDNA clone from tomato. Plant Cell 10: 2087–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, L., Sbicego, S., and Aphasizhev, R. 2003. Uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria: A complex business. RNA 9: 265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R. 2002. RNA-protein interactions that regulate pre-mRNA splicing. Gene Expr. 10: 79–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, R.S., Barton, D.J., Flanegan, J.B., and Kirkegaard, K. 1997. Poliovirus RNA recombination in cell-free extracts. RNA 3: 624–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolskaya, E.A., Romanova, L.I., Blinov, V.M., Viktorova, E.G., Sinyakov, A.N., Kolesnikova, M.S., and Agol, V.I. 1987. Studies on the recombination between RNA genomes of poliovirus: The primary structure and nonrandom distribution of crossover regions in the genomes of intertypic poliovirus recombinants. Virology 161: 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey, M. and Holmes, E.C. 1999. Evolutionary aspects of recombination in RNA viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 80: 2535–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]