Abstract

In addition to splicing, group I intron RNA is capable of an alternative two-step processing pathway that results in the formation of full-length intron circular RNA. The circularization pathway is initiated by hydrolytic cleavage at the 3′ splice site and followed by a transesterification reaction in which the intron terminal guanosine attacks the 5′ splice site presented in a structure analogous to that of the first step of splicing. The products of the reactions are full-length circular intron and unligated exons. For this reason, the circularization reaction is to the benefit of the intron at the expense of the host. The circularization pathway has distinct structural requirements that differ from those of splicing and appears to be specifically suppressed in vivo. The ability to form full-length circles is found in all types of nuclear group I introns, including those from the Tetrahymena ribosomal DNA. The biological function of the full-length circles is not known, but the fact that the circles contain the entire genetic information of the intron suggests a role in intron mobility.

Keywords: Didymium, group I intron, ribozyme hydrolysis, RNA circles, Tetrahymena

INTRODUCTION

Group I introns are widespread in nature, but with a notable sporadic occurrence. Whereas organellar group I introns have been identified in rRNA, mRNA, and tRNA transcription units, the nuclear group I introns are confined to the rRNA transcription units (Johansen et al. 1996). The group I introns are subdivided into five main groups (A–E) and about 10 subgroups based on differences in primary sequence and secondary structure features (Michel and Westhof 1990). All of the approximately 1000 known nuclear group I introns appear to belong to the IC1, IE, or IB subclass, with the IC1 being the most common class (Cannone et al. 2002; Jackson et al. 2002). Group I introns have been studied from two different perspectives: (1) as a selfish genetic element, and (2) as a ribozyme responsible for its own splicing reaction. Several observations support the notion of group I introns as selfish genetic elements. First, group I introns catalyze their own excision, although secondarily recruited host factors are implicated in many instances (Lambowitz et al. 1999). Second, the presence of a group I intron appears to have little effect on the host (see Nielsen and Engberg 1985 for an analysis of the Tetrahymena intron). Third, the mobility of group I introns within species is well documented and occurs by allelic homing, initiated by cleavage of the intron-lacking allele by an intron homing endonuclease (Lambowitz and Belfort 1993). Recently, a group I intron residing in a mitochondrial rRNA gene of yeast has been shown to undergo cyclical rounds of invasion, degradation, and loss of a functional homing endonuclease (Goddard and Burt 1999). These events are apparently independent of the host genome. The evidence for intron mobility between species is based on sequence comparison and appears solid (Bhattacharya 1998). The mechanism could be homing at the RNA level followed by reverse transcription and DNA recombination, but this has hitherto escaped experimental proof.

The studies of group I intron ribozyme features have been dominated by the Tetrahymena thermophila rDNA intron (Tth.L1925). The initial demonstration of the intron as a ribozyme by Cech and coworkers (Kruger et al. 1982) triggered a series of studies of the structural basis for the activity, culminating in crystal and solution structures of major parts of the RNA molecule (Golden et al. 1998; Kitamura et al. 2002). Although the splicing process has been in focus, other reactions of the intron have also been studied. In particular it was noted that the excised intron was capable of undergoing circularization reactions leading to variants of truncated circles (Zaug et al. 1983). These circles were shown to be very short-lived in vivo, as for the case of the linear intron (Brehm and Cech 1983). Furthermore, it was noted that the formation of full-length circles in vitro occurs as a result of hydrolysis at the 3′ splice site (SS) and subsequent transesterification at the 5′ SS (Been and Cech 1986; Inoue et al. 1986). These reactions were reported to be minor, and the full-length circular RNA was barely detected after incubation of pre-rRNA at splicing conditions. Finally, reversal of the splicing process was noted in the early studies and led to the hypothesis that intron mobility can occur by reverse splicing (Woodson and Cech 1989). From the Tetrahymena studies, it is noteworthy that all intron products are short-lived in vivo and that no alternative pathways that benefit the intron have been demonstrated. Thus, it appears that the Tetrahymena intron has become adapted to its host and shows very little evidence of an existence outside its exon context.

A contrasting view on intron biology is provided by the most complex group I introns, the twin-ribozyme introns found in SSU rDNA of the myxomycete Didymium and the amoebaeflagellate Naegleria. These introns contain a canonical group I splicing ribozyme (GIR2) harboring a self-cleaving group I-like ribozyme (GIR1) and a homing endonuclease gene (HEG) inserted into a peripheral loop (for review, see Einvik et al. 1998a; Johansen et al. 2002). Our studies of the intron in Didymium iridis (Dir.S956-1) have revealed that the structural complexity is paralleled by a complex biology. The mobility of Dir.S956-1 between strains has been experimentally verified to occur by homing (Johansen et al. 1997). The homing endonuclease (I-DirI) is expressed from the excised intron by a combination of intron-specific mechanisms and adaptation to the RNA polymerase II expression pathway of the host (Vader et al. 1999). Here, the 5′ end of the I-DirI mRNA is generated by the cleavages catalyzed by DiGIR1 and appears to lack a 5′ cap nucleotide. The open reading frame (ORF) is interrupted by a short spliceosomal intron and maturation of the mRNA involves splicing of this ORF intron by host factors as well as polyadenylation. During starvation-induced encystment of the Didymium cells, an alternative processing of pre-rRNA leads to the formation of an RNA species that is cleaved by DiGIR1 at the 5′ end, but retains the spliceosomal intron and the internal transcribed spacers (Vader et al. 2002). This RNA is hypothesized to act as a precursor for I-DirI mRNA upon encystment. Finally, full-length intron circles are formed as a major product during RNA processing at splicing conditions in vitro (Johansen and Vogt 1994; Decatur et al. 1995) and are also easily detectable in vivo (Vader et al. 1999, 2002). Truncated intron circles similar to those of the Tetrahymena intron have not been observed for Dir.S956-1.

In this report, we explore the formation of full-length circular intron RNA from the D. iridis rDNA group I intron Dir.S956-1. We demonstrate that full-length circles are formed by an intron RNA-processing pathway that is distinct from intron splicing and incompatible with the formation of functional rRNAs from the same transcripts. Then we examine the intron RNA processing of representatives of nuclear group I introns, including those from several Tetrahymena species. We conclude that the formation of full-length intron circles following 3′ SS hydrolysis is a general feature of nuclear group I introns.

RESULTS

The 5′-exon-intron RNA is the precursor in the formation of full-length DiGIR2 circles

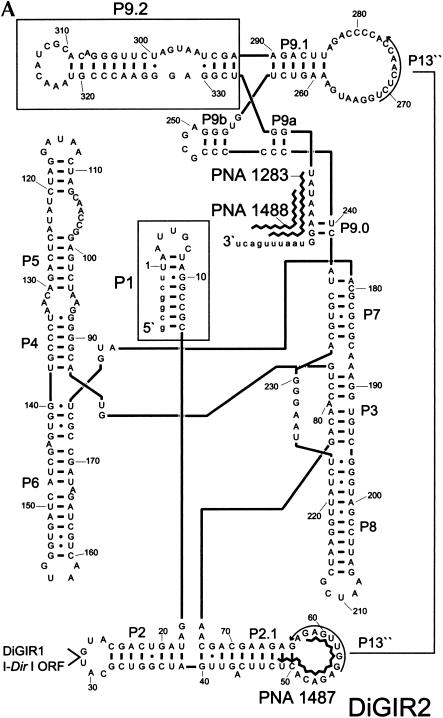

When the Dir.S956-1 intron from D. iridis rDNA is transcribed in vitro and analyzed after incubation at the splicing condition, a complex pattern of at least 11 different RNA species appears. These RNAs have previously been characterized by a variety of methods including G-labeling, primer extension, RT-PCR, and analysis of mutants (Johansen and Vogt 1994; Decatur et al. 1995; Einvik et al. 1998a,b), and found to include ligated exons, excised introns, full-length intron circles, and RNA species generated by hydrolysis at the 3′ SS or internal processing sites. DiGIR2 is a deletion construct of Dir.S956-1 that contains only the splicing ribozyme (Decatur et al. 1995). In vitro splicing of DiGIR2 generated the same RNAs as those found for Dir.S956-1, except those resulted from DiGIR1 cleavage, and corresponding RNA products were formed in comparable ratios in DiGIR2 and Dir.S956-1 (Decatur et al. 1995). The DiGIR2 intron, which is schematically presented in Figure 1A ▶, was therefore chosen for further studies of the circularization reaction.

FIGURE 1.

Structural and hydrolytic features of DiGIR2. (A) Secondary structure model of DiGIR2. Structural segments important in this study (P1 and P9.2) are boxed, and specificities of the peptide nucleic acids PNA1283, PNA1487, and PNA1488 are indicated. (B) Incubation of 3′ SS hydrolyzed precursor RNA generates the full-length circular intron RNA. Individual RNA species were purified from gels and incubated under splicing conditions without GTP for various times (0, 30, and 60 min, indicated by triangles above lanes). RNAs were subsequently separated on an 8 M urea/4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.4× TBE buffer. The RNAs are the 5′-exon-intron RNA (5′E-Int), the intron RNA (Int), and the full-length circular intron RNA (FLC). The circularization junction in FLC was amplified by RT-PCR, sequenced, and verified to correspond to full-length intron circularization (data not shown).

Two different reaction mechanisms can be envisaged to explain the formation of full-length circular introns. In the first, full-length circular introns are generated by a guanosine (G) exchange reaction. Here, the 3′-terminal G (ωG) of the excised intron makes a nucleophilic attack on the phosphodiester bond at the 5′ terminus of the intron, resulting in a full-length intron circle and release of the noncoded G cofactor (Thompson and Herrin 1991). The second mechanism involves 3′ SS hydrolysis of the transcribed precursor RNA, followed by a nucleophilic attack of ωG at the 5′ SS. This reaction results in the release of the 5′ exon and formation of a full-length intron circle (Been and Cech 1986; Inoue et al. 1986).

Figure 1B ▶ presents an experiment that was designed to distinguish between the two proposed scenarios in processing of the DiGIR2 intron. The first lane shows the complex processing pattern resulting from incubation of gel-purified precursor RNA made by in vitro transcription at splicing conditions. RNAs representing the 5′-exon-intron RNA (5′E-Int) generated by 3′ SS hydrolysis of precursor, the excised intron (Intron), and the full-length circular RNA (FLC) were eluted from polyacrylamide gels and reincubated at splicing conditions without GTP. The 5′-exon-intron RNA give rise to circular intron and 5′-exon RNA, but the excised intron does not react further upon incubation. The circular DiGIR2 RNA is prone to reopening at the circularization site similar to the Dir.S956-1 full-length circle (Johansen and Vogt 1994). This was demonstrated by primer extension analysis of the linear intron, confirming that the 5′ end corresponds to the 5′ nucleotide of the intron (without the noncoded G; data not shown). The G-exchange mechanism was ruled out by an experiment in which the intron was 5′-end labeled by incubation with [α-32P]GTP. No G release could be observed by TLC analysis upon reincubation of the isolated G-labeled intron (data not shown). From these experiments we conclude that full-length circularization of intron RNA occurs by 3′ SS hydrolysis of the transcribed precursor, followed by circularization of the 5′-exon-intron RNA at the 5′ SS by transesterification.

Splicing and circularization of DiGIR2 follows independent reaction pathways

The above experiments show that the splicing and circularization pathways coexist and are approximately equally active in converting precursor RNA into products. In different experimental approaches based on site-directed mutagenesis, PNA inhibition, and GTP competition, we were able to shift the balance between the two pathways. The first approach involves selective repression of 3′ SS hydrolysis by site-directed mutagenesis. We observed that two paired segments in the P9 subdomain (P9b and P9.2) are important structures in 3′ SS hydrolysis of DiGIR2 (P. Haugen, M. Andreassen, Å.B. Birgisdottir, and S. Johansen, unpubl.). Here, a time course splicing analysis of the P9 mutant DiGIR2-ΔP9.2 shows that the splicing reaction is not affected compared to wild-type DiGIR2, but hydrolysis-dependent products such as 3′-exon and full-length intron circle are significantly reduced. Thus, incubation of the DiGIR2-ΔP9.2 transcript resulted in an almost complete shift towards the splicing pathway supporting independent reaction pathways of splicing and 3′ SS hydrolysis, and that each pathway has a fundamental difference in RNA structural requirements (P. Haugen, M. Andreassen, Å.B. Birgisdottir, and S. Johansen, unpubl.).

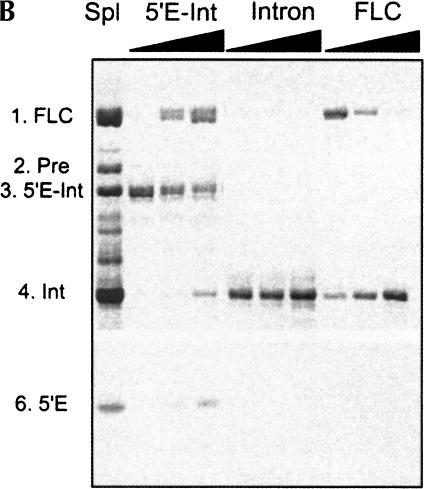

The second approach involves interference of wild-type DiGIR2 processing with antisense PNAs. In these experiments, a modified transcription reaction was used to allow binding of the PNA to its target (see Materials and Methods). Figure 2 ▶ (left panel) shows that reactions at the 3′ SS (second step of splicing and 3′ SS hydrolysis) are completely shut down when processing takes place in the presence of a 14-mer PNA complementary to the 3′ SS region (PNA1488; see Fig. 1A ▶). However, the first step of splicing appears stimulated several-fold in a PNA concentration-dependent manner (accumulation of the 5′-exon and intron-3′-exon RNAs). The effect of the PNA is sequence-specific because a mutated RNA with an altered target sequence was refractory to inhibition with PNA1488, and the inhibition could be restored by using a PNA complementary to the mutated target (data not shown). PNA1283 (Fig. 2 ▶, central panel) is also complementary to the 3′ SS region but has a shorter stretch (13 positions) of complementarity than PNA1488 involving only five positions of the 3′-exon. At low to intermediate concentrations of this PNA, 3′ SS hydrolysis is inhibited whereas splicing is stimulated up to 10-fold compared to incubation without PNA. The experiments with PNA1488 and PNA1283 show that the circularization pathway can be completely inhibited and the splicing pathway stimulated in the same experiment. PNA1487 was designed to achieve the opposite effect. This PNA is complementary to L2.1 in DiGIR1 (see Fig. 1A ▶), a structure known to be involved in a tertiary reaction (P13) with sequences in L9.1 (M. Andreassen and S. Johansen, unpubl.). Figure 2 ▶ (right panel) shows that PNA1487 has an inhibitory effect of both the hydrolysis and splicing pathways, an observation that corroborates our findings from mutational analysis of P13 in DiGIR2 (M. Andreassen and S. Johansen, unpubl.). However, in the PNA1487 experiment, a shift in the ratio between reaction products of the two pathways is observed (e.g., compare ligated exon to 3′-exon) in favor of the hydrolysis pathway at increasing PNA concentrations. The PNA experiments show that the splicing and circularization pathways can be dramatically and differentially affected by interference with the structure of the RNA without changing its sequence.

FIGURE 2.

PNA inhibition experiments. DiGIR2 templates were transcribed in the presence of PNA1488, PNA1283, or PNA1487 complementary to the 3′ SS or to the L2.1 (see Fig. 1A ▶). Different amounts of PNA were included with the transcription reaction (0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 25 pmole/10 μL) and the transcripts analyzed on 8 M urea/5% polyacrylamide gels. The positions in the gels of the relevant RNA species are indicated. Note that the DiGIR2 used in these experiments has a longer 3′ exon compared to that used in other experiments.

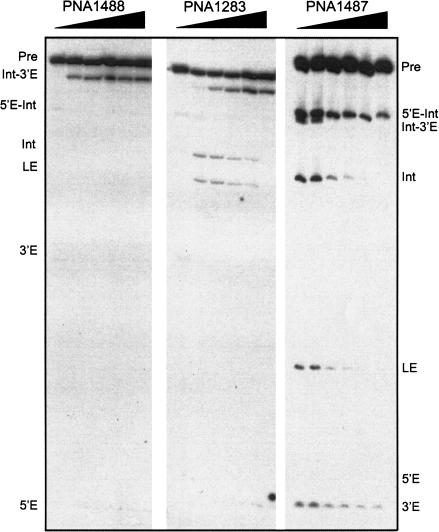

In the third set of experiments, the balance between the splicing and circularization pathways was simply shifted by varying the concentration of the guanosine cofactor (exoG) added to the splicing reaction. The rationale of the experiment is that exoG and the terminal intron guanosine (ωG) compete for the P7 guanosine-binding site of the DiGIR2 intron. Thus, at low GTP concentrations, we expected hydrolysis and circularization to dominate. Figure 3 ▶ presents time course experiments of DiGIR2 RNA at five different concentrations of GTP. As expected, the result shows that no splicing (e.g., formation of ligated exons) takes place in the absence of GTP. The products of 3′ SS hydrolysis (5′-exon-intron and 3′-exon RNAs) are seen to accumulate (RNAs 3 and 7). Similar observations are made of the circular intron species (RNA1) and free 5′-exon (RNA6), both generated by further processing of the 5′-exon-intron (RNA3). The presence of linear intron (RNA4) is due to reopening of RNA1. In the presence of GTP, the two reaction pathways coexist over a wide range of concentrations (2–2000 μM GTP). However, at 2000 μM GTP, the hydrolysis pathway appears suppressed (compare relative intensities of RNAs 1, 6, and 7 to RNA6 at 20 μM and 2000 μM GTP), consistent with a competitive behavior of the two pathways.

FIGURE 3.

Competition between added exogenous guanosine (GTP) and terminal guanosine (ωG) in DiGIR2 intron splicing and 3′ hydrolysis. The primary transcripts (Pre) were incubated under splicing conditions at varying GTP concentrations (0, 2, 20, 200, and 2000 μM) in time course experiments (0, 2, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min). RNAs were subsequently separated on an 8 M urea/5% polyacrylamide gel. The positions in the gels of the relevant RNA species are indicated. Note that the RNA species slightly smaller than RNA 3 present at early time points and high GTP concentrations corresponds to an Intron-3′-exon (Int-3′E) RNA. The circular species (RNA1) was eluted from the gels and purified. The circularization junction was amplified by RT-PCR and sequenced and found to correspond to a full-length intron circle (data not shown).

Taken together, the experimental approaches based on mutagenesis, PNA inhibition, and GTP competition confirm the existence of two independent reaction pathways of DiGIR2 processing, that is, the circularization pathway and the splicing pathway. Furthermore, the data support that the two pathways are competing in processing of the precursor RNA transcript. Whereas the circularization pathway is initiated by 3′ SS hydrolysis, the splicing pathway is initiated by transesterification at the 5′ SS.

Structural requirements in full-length circularization of DiGIR2 intron RNA

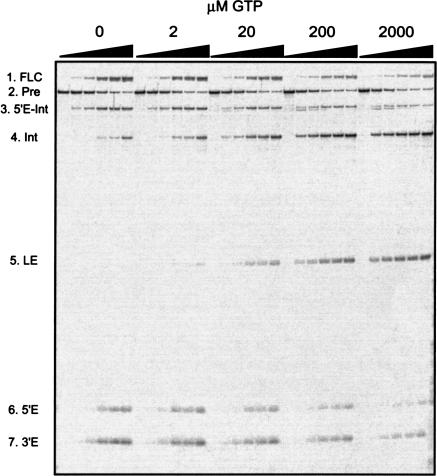

We observed recently that DiGIR2 mutants with a significant reduction in full-length circle formation (e.g., ΔP9.2 and L9bUUCG) were also impaired in 3′ SS hydrolysis (P. Haugen, M. Andreassen, Å.B. Birgisdottir, and S. Johansen, unpubl.). To investigate if these mutations directly affected full-length intron circularization, 3′ SS hydrolysis, or both reactions, mutant and wild-type DiGIR2 transcripts terminated exactly at ωG were produced and tested at standard conditions in a time course cleavage analysis (Fig. 4A ▶). Processing of the two transcripts was observed to occur in parallel, both resulting in accumulation of full-length circles as evidenced by RT-PCR and sequencing of the circularization junction. This observation differs significantly from results using similar transcripts including the 3′ exon. Whereas circle formation was unaffected by the P9.2 deletion in the above experiment (Fig. 4A ▶), hydrolytic 3′ SS cleavage in this mutant was not observed after 24 h of incubation (P. Haugen, M. Andreassen, Å.B. Birgisdottir, and S. Johansen, unpubl.) of transcripts including the 3′ exon. These experiments show that full-length intron circularization of DiGIR2 is independent on the structures in P9 known to be essential for 3′ SS hydrolysis, but rather depend on the free ωG 3′ terminus generated by hydrolytic cleavage.

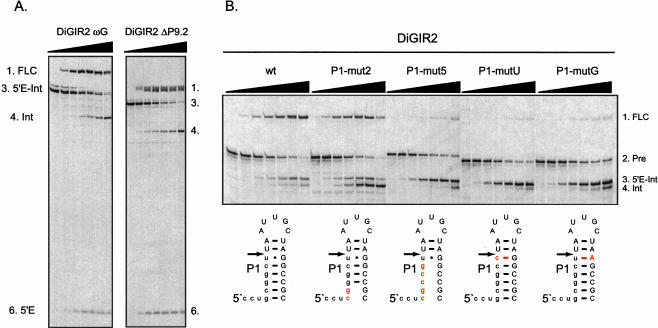

FIGURE 4.

Structural requirements in full-length intron circularization. (A) Analysis of circularization of intron transcripts ending exactly in ωG. RNA transcripts corresponding to 5′-exon-intron (5′E-Int) of DiGIR2 and DiGIR2-ΔP9.2 were incubated under splicing conditions in time course experiments (0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min), and subsequently separated on an 8 M urea/5% polyacrylamide gel. (B) The importance of the P1 segment in full-length circularization of DiGIR2. RNA transcripts corresponding to different P1 mutants were incubated under splicing conditions in time course experiments (0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min), separated on an 8 M urea/5% polyacrylamide gel, and analyzed for full-length circle formation.

In full-length circle formation, the 3′ hydroxyl group of ωG is proposed to attack the 5′ SS of the 5′ exon-intron RNA, suggesting an important role of the P1 segment. P1 contains base pairs between the 5′ exon and the internal guide sequence (IGS) within the intron. To test for a functional role of the P1 in circle formation, four different transcripts mutated in P1 were generated in a wild-type DiGIR2 intron background (Fig. 4B ▶). Two mutations affected 2 and 5 bp (P1-mut2 and P1-mut5), respectively, at the basis of the P1 stem, and two mutations affected the conserved GU wobble base pair (P1-mutU and P1-mutG) at the 5′ SS. Whereas all transcripts possess an approximately equal hydrolytic activity at the 3′ SS, significant differences in the amounts of circle formation were observed. Only P1-mut2 generates wild-type amounts of circles, whereas all other mutants (P1-mut5, P1-mutU, and P1-mutG) show a significant decrease in circle formation. The sequences of the circularization junctions were confirmed to correspond to full-length circles in wild-type and P1-mut2, whereas direct sequencing of RNA1 circle junctions from the other mutants revealed circle heterogeneity. By cloning and sequencing of individual RT-PCR products, these were identified to include truncated circles lacking 1, 104, and 111 nt of the intron 5′ end, as well as small amounts of full-length circles. From these experiments, we conclude that full-length circularization depends on a P1 segment containing the GU wobble base pair at the 5′ SS as well as a 3–5 bp basal stem.

Formation of full-length circles from the hydrolysis pathway is a general feature among nuclear group I introns

We recently reported that formation of full-length intron circles is a general feature of complex nuclear group I introns that contain HEGs or HEG-like sequences (Haugen et al. 2002). Furthermore, most of the simple group I introns (introns that encode only canonical group I ribozymes) tested also generate full-length circles as the main circular intron species (E.W. Lundblad and S. Johansen, unpubl.). To evaluate whether the formation of full-length intron circles follows the same 3′ SS hydrolysis pathway as seen in DiGIR2, the 5′-exon-intron RNAs from various nuclear group I introns were eluted from the polyacrylamide gels, purified, and reincubated at standard reaction conditions. The introns selected represent different host organisms, insertion sites, and subclasses, and are listed in Table 1 ▶. In all cases, circular RNA species were formed and analysis of the circle junction sequence based on the RT-PCR sequencing approach confirmed that these correspond to full-length intron circles. Little is known about the amount of circular RNA found in vivo. In the case of Dir.S956-1, full-length circular RNA could be readily detected by Northern blotting of whole-cell RNA fractionated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. The identity of the signal was deduced from comigration with full-length RNA formed in vitro and parallel sequencing of RT-PCR products derived from whole-cell RNA. The amount was estimated to be hundreds of copies per cell and was relatively constant over time in a starvation experiment (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Nuclear group I introns analyzed for circle formations

| Full-length circlese | IGS circlesf | ||||||

| Introna | Speciesb | Subclassc | HEGd | in vitro | in vivo | in vitro | in vivo |

| Cla.L2066 | Comatricha laxa | IE | − | + | n.a. | − | n.a. |

| Dir.S956-1 | Didymium iridis | IE | + (P2) | + | + | − | − |

| Dir.S956-2 | D. iridis | IC1 | + (a-P8) | + | + | − | − |

| Fse.S516 | Fuligo septica | IC1 | − | + | + | − | − |

| Fse.S911 | F. septica | IC1 | − | − | + | + | − |

| Fse.S956 | F. septica | IC1 | − | + | − | − | − |

| Fse.S1065 | F. septica | IC1 | − | + | + | − | − |

| Fse.L569 | F. septica | IC1 | − | − | + | + | − |

| Fse.L1090 | F. septica | IC1 | − | + | + | − | − |

| Fse.L1898 | F. septica | IC1 | − | + | + | + | − |

| Fse.L1911 | F. septica | IC1 | − | + | − | + | + |

| Fse.L2500 | F. septica | IC1 | − | − | + | + | − |

| Fse.L2584 | F. septica | IC1 | − | − | + | + | + |

| Nae.L1926 | Naegleria NG874 | IC1 | + (P1) | + | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Nan.S516 | N. andersoni | IC1 | + (P6) | + | n.a. | − | n.a. |

| Ngr.S516 | N. gruberi | IC1 | + (P6) | n.a. | + | n.a. | − |

| Nja.S516 | N. jamiesoni | IC1 | + (P6) | + | n.a. | − | n.a. |

| Nmo.L2563 | N. morganensis | IC1 | + (P1) | + | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Ppo.L1925 | Physarum polycephalum | IC1 | + (P1) | + | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Psp.S1506 | Porphyra spiralis | IC1 | + (a-P1) | + | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Tel.L1925 | Tetrahymena elliotti | IC1 | − | + | − | + | + |

| Tle.L1925 | T. leukophrys | IC1 | − | + | − | + | + |

| Tma.L1925 | T. malaccensis | IC1 | − | + | − | + | + |

| Tsi.L1925 | T. silvana | IC1 | − | + | n.a. | + | n.a. |

| Tth.L1925 | T. thermophila | IC1 | − | + | − | + | + |

| Ttr.L1925 | T. tropicalis | IC1 | − | + | − | + | + |

aName of intron reflecting the insertion site in the small (S) and large (L) subunit ribosomal RNA genes.

bHost species of introns. All are myxomycete protists except Naegleria (amoeboflaggelate), Porphyra (red algae), and Tetrahymena (ciliate).

cIntron subclass based on structural features.

dPresence or not of a homing endonuclease gene (HEG). Location of HEG within the ribozyne is indicated (Pn), as well as sense or antisense (a) orientation.

eIntron circles by ligation of ωG and the first nucleotide of the intron.

fIntron circles by ligation of ωG and a nucleotide at, or close to, the internal guide sequence (IGS).

(n.a.) not analyzed.

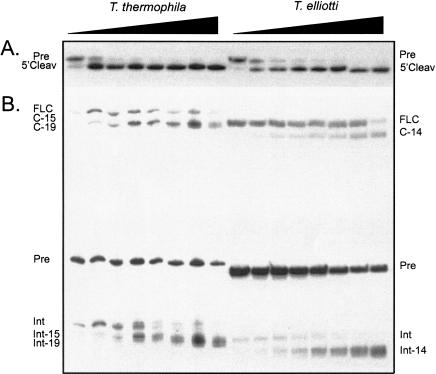

The group I intron from T. thermophila (Tth.L1925) serves as a prototype intron in studying RNA structure and reaction (Cech and Golden 1999). The main circular species formed upon incubation of Tth.L1925 at in vitro splicing conditions are truncated by 15 and 19 nt in their 5′ end, and full-length circles have only been detected as a minor and rare RNA species (Been and Cech 1986; Inoue et al. 1986). Truncated circles are similarly found in other species of Tetrahymena (Engberg et al. 1988) and the circularization sites are in accordance with a model based on base pairing of the 5′ end of the intron at or near the IGS (Been and Cech 1986,Been and Cech 1987). Circularization has frequently been studied by characterization of the release of a 5′ end fragment carrying a 32P label that was added by splicing in the presence of [α-SUP32P]GTP. In this approach, only full-length circles formed by the G-exchange pathway (Thompson and Herrin 1991) would be observed, whereas full-length circles formed from the 5′-exon-intron hydrolysis product would escape detection. To reevaluate the ability of Tetrahymena introns to produce full-length circles, RNA from in vitro splicing reactions or cellular RNA isolated from whole cells or nuclei from six species were analyzed. The analysis was performed by RT-PCR using primers flanking the circularization site followed by isolation and sequencing of the individual PCR products (summary of results is presented in Table 1 ▶). In the in vitro reactions, all species produced a mixture of full-length circles and truncated circles. The proportion of full-length circles varied, with the largest proportion found in Tetrahymena elliotti and the smallest in T. thermophila. The truncated circles were in all cases in agreement with the IGS-model for formation of truncated circles (Been and Cech 1986,Been and Cech 1987). In the experiments with whole-cell or nuclear RNA, only truncated circles were found. In some cases, the sites of truncation differed from those found in vitro (H. Nielsen, unpubl.). T. thermophila and T. elliotti introns were selected for time-course studies of the two steps in the circularization pathway. The hydrolysis step was analyzed using transcripts lacking the 5′ exon and P1 of the intron (Fig. 5A ▶). Both introns exhibited very fast 3′ SS cleavages. The circularization step was analyzed with transcripts including the 5′ exon and the intron terminating in ωG (Fig. 5B ▶). In both cases, a relatively slow formation of full-length circles was observed, followed by circle reopening and recircularization at one (T. elliotti) or two (T. thermophila) internal sites. The experiments were performed with transcripts from PCR products, but similar results were obtained with gel-purified RNAs from splicing reactions, although the kinetics of the reactions differed with these RNAs. We conclude that the Tetrahymena intron is similar to other nuclear group I introns with respect to formation of full-length circles, although the well-studied T. thermophila generally result in a low accumulation of these molecules in splicing experiments.

FIGURE 5.

Hydrolysis at the 3′ SS and circularization of Tetrahymena introns. The two steps of the circularization pathway were analyzed independently in homologous introns from two different Tetrahymena species (T. thermophila and T. elliotti). (A) Intron transcripts lacking P1 (and consequently the 5′ SS) were analyzed for the 3′-SS hydrolysis step of the reaction. (B) Intron transcripts that include the 5′ exon, but terminate exactly at the ωG, were analyzed for the circularization step of the reaction. All the experiments were performed as a time-course experiment (0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120 min) using standard splicing conditions and the RNAs analyzed on either 8 M urea/6% polyacrylamide gels (A) or 8 M urea/4% polyacrylamide gels in 0.4× TBE buffer (B). The positions in the gel of the various RNAs from T. thermophila and T. elliotti are indicated to the left and right, respectively. For example, C-15 and Int-15 refer to circular and linear intron species lacking 15 nt at the 5′ terminal. The identity of the circular species were verified by gel purification, RT-PCR, and sequencing (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

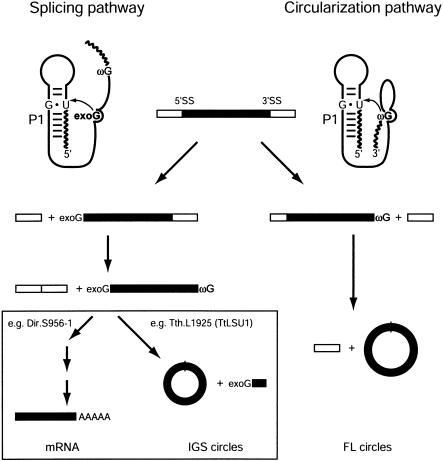

We have examined the formation of full-length intron RNA circles in nuclear group I introns. Full-length intron RNA circularization appears to occur in a two-step reaction consisting of sequential site-specific hydrolysis and transesterification reactions (Fig. 6 ▶). Circularization is initiated by hydrolysis of precursor transcript RNA at the 3′ SS terminal guanosine (ωG), a reaction dependent on defined RNA structural elements within the P9 subdomain not important for intron splicing. In a subsequent reaction, the ωG at the free 3′ end of the intron RNA attacks the 5′ SS, resulting in a ligated full-length intron circle and release of the free 5′-exon RNA. Full-length intron circularization was found to be dependent on a functional P1 segment containing a base-paired IGS as well as the GU wobble base pair at the 5′ SS. Thus, the second step in full-length circularization appears similar to the first step in group I intron splicing, except in that the nucleophilic attack at the 5′ SS is performed by ωG instead of the noncoded exogenous guanosine cofactor. A comparative analysis involving various nuclear group I introns from different subclasses, insertion sites, and hosts, including a collection of Tetrahymena introns, supports that the formation of full-length circles from the 3′ SS hydrolyzed precursor is a general feature among the nuclear group I introns.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic representation of the two processing pathways in nuclear group I introns. The splicing pathway (left) is initiated by binding of exogenous guanosine (exoG) to the intron internal G binding site followed by nucleophilic attack at the 5′ SS presented in the P1 context. Two transesterification reactions referred to as the first and second steps of splicing result in a spliced out intron with the exoG attached at the 5′ end and spliced exons. The spliced out intron can undergo one of two different sets of reactions. In twin-ribozyme introns (e.g., Dir.S956-1), a set of reactions leads to the formation of an mRNA encoding a homing endonuclease. In most nuclear group I introns (e.g., Tth.L1925), the ωG attacks an internal phosphodiester bond close to the 5′ end presented in a way analogous to the P1 presentation of the 5′ SS. As a result, shortened circles are formed (IGS circles). The circularization pathway (right) is initiated by hydrolysis at the 3′ SS followed by nucleophilic attack of ωG at the 5′ SS presented in the P1 context. This pathway involves one site-specific hydrolysis reaction and one transesterification and results in the formation of full-length intron circles, leaving the exons unligated.

Formation of full-length circular RNA in DiGIR2 constitutes a distinct pathway in processing

The conclusions drawn from the DiGIR2 experiments are likely to apply to the full-length Dir.S956-1 intron as well. During in vitro processing of Dir.S956-1, the corresponding intermediates and products accumulate as expected for the circularization pathway (Johansen and Vogt 1994; Decatur et al. 1995; Einvik et al. 1998a). In vivo, the product of the circularization pathway is easily detectable by Northern blotting analysis (Vader et al. 1999, 2002). Thus, we conclude that circularization constitutes a distinct processing pathway for the Dir.S956-1 intron. Formation of full-length intron circles generates discontinuous nonfunctional ribosomal RNAs, indicating that the circularization pathway benefits the intron at the expense of the host genome and supports the notion of group I introns as selfish elements. The product of the circularization pathway has been observed in all examples of nuclear group I introns analyzed. In the case of the canonical T. thermophila intron, the pathway appears to be suppressed in vitro and full-length intron circles are not observed in vivo. How this suppression acts is not known, but the hydrolysis step is likely to be involved because the Tetrahymena intron catalyze 3′ SS hydrolysis at a compatible rate compared to that of DiGIR2 (P. Haugen and S. Johansen, unpubl.). In all other Tetrahymena species tested, the suppression of intron circularization in vitro is relieved to a varying degree. Here, the pathway leading to full-length circles is observed to occur in parallel to the splicing pathway and the subsequent formation of truncated circles.

Binding of exoG or ωG to the guanosine-binding site appears to be the committed step in the expression of the two pathways

We have shown that the splicing and circularization pathways occur in parallel during processing of DiGIR2 and that the balance between the two can be experimentally shifted. In vitro, the processing of DiGIR2 at splicing conditions leads to approximately equal accumulation of the products of the two pathways. In vivo, splicing is by far the dominant of the two pathways. This indicates a mechanism that suppresses the circularization pathway in vivo or, alternatively, actively regulates this pathway to ensure efficient synthesis of functional ribosomal RNA. A candidate target for such a mechanism is the decisive event in processing of the DiGIR2 intron, namely, the binding of either the exogenous guanosine cofactor (exoG) or the 3′ intron terminal G (ωG) to the single guanosine-binding site located in P7, and the subsequent activation of the catalytic activity. It is well documented that a single guanosine-binding site exists in the Tetrahymena intron (Michel et al. 1989; Been and Perrotta 1991), although other structural elements may participate in GTP binding, for example P1 (McConnell and Cech 1995; Guo and Cech 2002). The choice between exoG and ωG in this regulation is reminiscent of that between exoG and ωG during splicing itself. Here, exoG binding must be preferred prior to the first step for splicing to occur as an ordered process. In an analysis of a trans-splicing model based on the L-21 ScaI Tetrahymena ribozyme, Zarrinkar and Sullenger (1998) showed that the relative affinities for the two ligands are modulated such that they compete during the first step but that no competition is apparent during the second step when ωG is bound tightly. This modulation was taken as an explanation of the ordered sequence of events during splicing. The underlying mechanism that governs the choice between exoG and ωG in regulating splicing versus circularization in DiGIR2 is not known, but several mechanisms can be envisaged: (1) competition based on different affinities of the two guanosines for the P7 binding site; (2) a folding of the intron that excludes ωG from binding and thus promotes splicing by default; (3) regulation of the catalytic activity, for example by folding of structural elements involved in catalysis or their positioning relative to the substrate. In this view, binding of ωG to the binding site could be unproductive. We show that the rate of precursor removal during DiGIR2 processing is independent of the GTP concentration. The balance is shifted such that splicing is completely suppressed in the absence of GTP but circularization is moderately suppressed at very high GTP concentrations (Fig. 3 ▶), supporting that the two guanosine ligands compete for the same binding site as was shown for the Tetrahymena ribozyme. However, the suppression of hydrolysis at high GTP concentrations was not observed in Tetrahymena (Zarrinkar and Sullenger 1998). These differences may be explained by structural differences in P7 of the two ribozymes or by different binding modes of ωG in the two pathways. Other obvious candidates for a regulatory element in the circularization pathway are the P9.2 and P9b structures shown to be specifically required for 3′-SS hydrolysis (P. Haugen, M. Andreassen, Å.B. Birgisdottir, and S. Johansen, unpubl.), but the involvement of these structures must await their further characterization. The choice between the two guanosine ligands appears to be the committed step in the expression of the two pathways.

Interestingly, binding of ωG during the second step of circularization may be a well-studied event in the Tetrahymena intron. In the paper describing the crystal structure of the Tetrahymena ribozyme, Golden et al. (1998) used a derivative in which a terminal G bound to the guanosine binding site could cleave the P1 duplex at positions consistent with that of full-length intron circularization. This reaction has no parallel in splicing or reverse splicing, but is equivalent to the second step of circularization. In a number of biochemical studies (Russell and Herschlag 1999), the L-21G414 derivative of the Tetrahymena ribozyme is used in a transesterification reaction with an oligonucleotide bound to the ribozyme by base pairing with the IGS. This reaction is described as the reverse of the second step of splicing, but could at least equally be representing the second step of full-length intron circularization.

The biological role of circular RNA species in nuclear group I introns

Two distinct categories of circular species with apparent biological functions are formed in processing reactions of group I intron RNAs: (1) full-length circular introns, and (2) truncated intron circles. According to the recently proposed invasion cycle of group I introns (Goddard and Burt 1999), the genetic element with an impact biological function is the mobile version of a group I intron that encodes an active homing endonuclease. One possible role of full-length circles could be as intermediates in the expression of the homing endonucleases. Comprehensive studies of I-PpoI homing and expression of the nuclease, which occurs from a nonpolyadenylated full-length intron RNA (Lin and Vogt 2000) in yeast, could not exclude that full-length circular introns play a significant role in mRNA stabilization or cytoplasmic translocation prior to translation (Haugen et al. 2002). Alternatively, the full-length intron circles are involved in group I intron mobility at the RNA level. Our recent observation that in vitro reverse splicing of DiGIR2 RNA into its cognate insertion site also occurs from the apparent full-length circular species (Å.B. Birgisdottir and S. Johansen; unpubl.), combined with the fact that the entire genetic information is preserved in full-length intron circles, makes it feasible that full-length intron circles are involved in the first step of retro-homing with the subsequent consequence of lateral intron transfers.

The second category of circular intron RNA species with an apparent biological significance is the truncated circles generated by ligation between ωG and an internal residue at or close to IGS within the 3′ half of the P1 segment. These circular species, which generate from excised intron RNAs through the splicing pathway, are below referred to as IGS circles. In many cases, as for the Tetrahymena introns, full-length circles and IGS circles coexist (see Table 1 ▶). One simple explanation could be that IGS circularization prevents fatal reverse splicing from occurring in cells by deleting short oligonucleotide sequences from the 5′ end of the intron RNA. An alternative view is that IGS circularization is a relic from a stage in the invasion cycle when the intron were mobile genetic elements harboring functional HEGs. Recent analyses of complex nuclear group I introns support a role of IGS processing (including IGS circularization) in regulation of the expression of intron HEGs located within the P1 loop segment 5′ of the IGS. The mobile Physarum intron Ppo.L1925, a close relative to the Tetrahymena introns, performs IGS processing in vivo directly linked to down-regulation of the I-PpoI homing endonuclease expression (Lin and Vogt 2000). Furthermore, in vitro analysis of similarly organized group I introns from Naegleria detected IGS processing and IGS circularization, suggested to play a role in up-regulation of their respective endonucleases (Haugen et al. 2002). Finally, several additional observations consistent with a strong link between IGS processing/circularization and expression regulation of the P1 intron HEGs have been noted. Here, introns with HEGs in P2 or P6 (Johansen and Vogt 1994; Decatur et al. 1995; Einvik et al. 1997), as well as antisense-oriented HEGs in P1 or P8 (Vader 1998; Haugen et al. 1999) do not possess any detectable IGS circularization or processing. Thus, a plausible proposal is that the biological role of both full-length intron circles and IGS intron circles are linked to mobility functions of complex group I introns. Although the full-length circles may play a direct role at the RNA level in lateral transfers through reverse splicing, IGS circles may have a more regulatory role in intron homing at the DNA level through homing endonuclease expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro transcription, purification of transcripts, and isolation of cellular RNAs

Standard in vitro transcription reactions were performed on linearized plasmids containing the appropriate insert or templates made by PCR. PCR products to be used as templates in transcription were made using Pfu DNA polymerase and purified using the GenElute PCR Kit (Sigma). A standard reaction contained 1 μg of plasmid DNA or 200 ng of PCR product in a volume of 25 μL of 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM spermidine, 30 mM DTT, 0.4 mM GTP, CTP, UTP, and ATP, and 10 U T7 RNA polymerase (Stratagene). For uniform labeling, either 0.3 μL of [35S]CTP (1000 Ci/mmole; Amersham Bioscience) or 1 μL of [α-32P]UTP (3000 Ci/mmole, Amersham Bioscience). Transcription of precursor RNA from templates encoding the Tetrahymena ribozyme was performed in 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 12 mM MgCl2, 4 mM spermidine, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM GTP, CTP, UTP, and ATP, and 10 U T7 RNA polymerase (Stratagene) for 1 h at 30°C. Transcripts were purified from polyacrylamide gels by diffusion into elution buffer (0.3 M NaAc, 1 mM EDTA) overnight at 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM GTP for 30 min at 4°C followed by filtration through a 0.45 mm filter (Millex) and precipitation by addition of 2.5 volumes of 96% EtOH. Whole-cell RNA and nuclear RNA from Tetrahymena was isolated according to published procedures (Pedersen et al. 1985).

In vitro mutagenesis, DNA cloning, RT-PCR, and DNA sequencing

The plasmid containing the DiGIR2 ribozyme has previously been described (Decatur et al. 1995). The mutant versions of DiGIR2 used in the analysis of P1 in circularization reactions were made by PCR using OP5 as the 3′ oligo (5′-CATACGTGTATCTGGACC) and one of the following as 5′-oligo: OP543 (5′-AATTAATAC GACTCACTATAGGGAACCTGCGGCTTAAATTGCTAGGCC; wild type), OP542 (5′-AATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAA CCTCGGGCTTAATTGCTAGGCC; P1-mut2), OP544 (5′-AAT TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAACCTCGCCGTTAATTGCTAG GCCGCG; P1-mut5), OP545 (5′-AATTAATACGACTCAC TATAGGGAACCTGCGGCCTAATTGCTAGG CCGCGA; P1-mutU), and OP546 (5′-AATTAATACGACTCACTATAGG GAACCTGCGGCTTAATTGCTAAGCCGCGATAGTCAGCAT; P1mutG). The transcripts terminating in the 3′-terminal nucleotide of the intron (ωG) were made from PCR products that included a StuI restriction site at the end coding for the 3′ end of the RNA. The PCR products were made using OP39 (5′-AATTTAATAC GACTCACTATAGGG) as the upstream primer and OP539 (5′-ACTCAGGCCTTTATACCAGCCTCCC) as the downstream primer with wild-type and P9 plasmid DNA as templates, respectively. Following PCR, the templates were purified and digested with StuI to create the correct terminus of the template. PCR products were cloned into a blunt-end site of the pUC18 vector using the SureClone ligation kit (Amersham Bioscience) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RT-PCR was performed on gel-purified RNA or cellular RNA preparations using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Amersham Bioscience) with a specific primer followed by PCR using the same primer in combination with an additional primer. For analysis of the circularization site in the Didymium intron, OP85 (5′-AAGGTCGAGCTCACCCCA GATTC) and OP295 (5′-TACTTTCAGACACCCCGAAGGGGG GAGTAGCACG) were used. DNA sequencing was performed with the Thermo Sequenase Cycle Sequencing Kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) using either [α-33P]-radiolabeled ddNTPs or a sequencing primer labeled at its 5′ end using [γ-32P]ATP.

RNA processing

In vitro transcribed DiGIR2 RNA was reacted at 50°C for the indicated times in 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 15 mM MgCl2, 0.5 M KCl, 2 mM spermidine, and 5 mM DTT. In splicing reactions, varying concentrations of GTP was included (standard at 2 mM GTP). Transcripts of the Tetrahymena ribozymes were either spliced in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM GTP for 30 min at 30°C or circularized in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 200 mM NaCl, for 30 min at 42°C.

PNA experiments

The PNAs used in the present study were synthesized in a peptide synthesizer using Boc-chemistry according to published procedures (Christensen et al. 1995). A carboxy-terminal lysine residue was included to aid solubility. After purification by high-performance liquid chromatography, the PNAs were characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Three PNAs were used, PNA1283 [(kemptide) AGCAATTACCTTTATA-Lys-NH2], PNA1487 (H-TCTCAACCT CTGTGAG-Lys-NH2), and PNA1488 (H-TCAAATTACCTTTAALys-NH2). Processing experiments of DiGIR2 in the presence of PNA was carried out in the following way. First, the appropriate amount of PNA was pipetted into the tube. Then a transcription mixture was added consisting of 100 ng of template DNA, PNA binding buffer (final concentrations: 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM each of GTP, CTP, UTP and ATP plus a trace amount of [α-32P]UTP, 1 U RNasin (Promega), 5 U of T7 RNA polymerase (Stratagene), and dH2O to make the final volume 10 μL. The reactions were incubated for 30 min at the appropriate temperature, after which they were stopped by the addition of 10 μL of a urea-based gel loading buffer. The sample was then heated to 65°C for 5 min and analyzed on a 4% denaturing (urea) gel in 0.4× TBE buffer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from The Norwegian Research Council (S.J.), The Norwegian Cancer Society (S.J.), The Aakre Foundation for Cancer Research (S.J.), and The Danish Natural Science and Medical Research Councils (H.N.). We appreciate the generous gift of PNAs from Peter E. Nielsen.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ``advertisement'' in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5290903.

REFERENCES

- Been, M.D. and Cech, T.R. 1986. One binding site determines sequence specificity of Tetrahymena pre-rRNA self-splicing, trans-splicing, and RNA enzyme activity. Cell 47: 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1987. Selection of circularization sites in a group I IVS RNA requires multiple alignments of an internal template-like sequence. Cell 50: 951–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Been, M.D. and Perrotta, A.T. 1991. Group I intron self-splicing with adenosine: Evidence for a single nucleoside-binding site. Science 252: 434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, D. 1998. The origin and evolution of protist group I introns. Protist 149: 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm, S.L. and Cech, T.R. 1983. Fate of an intervening sequence ribonucleic acid: Excision and cyclization of the Tetrahymena ribosomal ribonucleic acid intervening sequence in vivo. Biochemistry 22: 2390–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannone, J.J., Subramanian, S., Schnare, M.N., Collett, J.R., D'Souza, L.M., Du, Y., Feng, B., Lin, N., Madabusi, L.V., Muller, K.M., et al. 2002. The Comparative RNA Web (CRW) Site: An online database of comparative sequence and structure information for ribosomal, intron, and other RNAs. BioMed Central Bioinformatics 3: 1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech, T.R. and Golden, B.L. 1999. Building a catalytic active site using only RNA. In The RNA world (eds. R.F. Gesteland et al.), pp. 321–349. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Christensen, L., Fitzpatrick, R., Gildea, B., Petersen, K.H., Hansen, H.F., Koch, T., Egholm, M., Buchardt, O., Nielsen, P.E., Coull, J., et al. 1995. Solid-phase synthesis of peptide nucleic acids. J. Pept. Sci. 1: 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decatur, W.A., Einvik, C., Johansen, S., and Vogt, V.M. 1995. Two group I ribozymes with different functions in a nuclear rDNA intron. EMBO J. 14: 4558–4568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einvik, C., Decatur, W.A., Embley, T.M., Vogt, V.M., and Johansen, S. 1997. Naegleria nucleolar introns contain two group I ribozymes with different functions in RNA splicing and processing. RNA 3: 710–720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einvik, C., Elde, M., and Johansen, S. 1998a. Group I twintrons: Genetic elements in myxomycete and schizopyrenid amoeboflagellate ribosomal DNAs. J. Biotechnol. 17: 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einvik, C., Nielsen, H., Westhof, E., Michel, F., and Johansen, S. 1998b. Group I-like ribozymes with a novel core organization perform obligate sequential hydrolytic cleavages at two processing sites. RNA 4: 530–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberg, J., Zaug, A.J., and Nielsen, H. 1988. Circularization site choice in the self-splicing reaction of the ribosomal RNA intervening sequence of Tetrahymena silvana. Mol. Gen. Life Sci. Adv. 7: 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, M.R. and Burt, A. 1999. Recurrent invasion and extinction of a selfish gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 13880–13885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden, B.L., Gooding, A.R., Podell, E.R., and Cech, T.R. 1998. A preorganized active site in the crystal structure of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Science 282: 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F. and Cech, T.R. 2002. In vivo selection of better self-splicing introns in Escherichia coli: The role of the P1 extension helix of the Tetrahymena intron. RNA 8: 647–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, P., Huss, V.A., Nielsen, H., and Johansen, S. 1999. Complex group-I introns in nuclear SSU rDNA of red and green algae: Evidence of homing-endonuclease pseudogenes in the Bangiophyceae. Curr. Genet. 36: 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, P., De Jonckheere, J.F., and Johansen, S. 2002. Characterization of the self-splicing products of two complex Naegleria LSU rDNA group I introns containing homing endonuclease genes. Eur. J. Biochem. 269: 1641–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, T., Sullivan, F.X., and Cech, T.R. 1986. New reactions of the ribosomal RNA precursor of Tetrahymena and the mechanism of self-splicing. J. Mol. Biol. 189: 143–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.A., Cannone, J.J., Lee, J.C., Gutell, R.R., and Woodson, S.A. 2002. Distribution of rRNA introns in the three-dimensional structure of the ribosome. J. Mol. Biol. 323: 35–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, S. and Vogt, V.M. 1994. An intron in the nuclear ribosomal DNA of Didymium iridis codes for a group I ribozyme and a novel ribozyme that cooperate in self-splicing. Cell 25: 725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, S., Muscarella, D.E., and Vogt, V.M. 1996. Insertion elements in ribosomal DNA. In Ribosomal RNA: Structure, evolution, processing, and function in biosynthesis (eds. R.A. Zimmermann and A.E. Dahlberg), pp. 89–108. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Johansen, S., Elde, M., Vader, A., Haugen, P., Haugli, K., and Haugli, F. 1997. In vivo mobility of a group I twintron in nuclear ribosomal DNA of the myxomycete Didymium iridis. Mol. Microbiol. 24: 737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, S., Einvik, C., and Nielsen, H. 2002. DiGIR1 and NaGIR1: Naturally occurring group I-like ribozymes with unique core organization and evolved biological role. Biochimie 84: 905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, A., Muto, Y., Watanabe, S., Kim, I., Ito, T., Nishiya, Y., Sakamoto, K., Ohtsuki, T., Kawai, G., Watanabe, K., et al. 2002. Solution structure of an RNA fragment with the P7/P9.0 region and the 3′-terminal guanosine of the Tetrahymena group I intron. RNA 8: 440–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, K., Grabowski, P.J., Zaug, A.J., Sands, J., Gottschling, D.E., and Cech, T.R. 1982. Self-splicing RNA: Autoexcision and autocyclization of the ribosomal RNA intervening sequence of Tetrahymena. Cell 31: 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambowitz, A.M. and Belfort, M. 1993. Introns as mobile genetic elements. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62: 587–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambowitz, A.M., Caprara, M.G., Zimmerly, S., and Perlman, P.S. 1999. Group I and group II ribozymes as RNPs: Clues to the past and guides to the future. In The RNA world (eds. R.F. Gesteland et al.), pp. 451–485. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Lin, J., and Vogt, V.M. 2000. Functional alpha-fragment of betagalactosidase can be expressed from the mobile group I intron PpLSU3 embedded in yeast pre-ribosomal RNA derived from the chromosomal rDNA locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 1428–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel, F. and Westhof, E. 1990. Modeling of the three-dimensional architecture of group I catalytic introns based on comparative sequence analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 216: 585–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, T.S. and Cech, T.R. 1995. A positive entropy change for guanosine binding and for the chemical step in the Tetrahymena ribozyme reaction. Biochemistry 34: 4056–4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel, F., Hanna, M., Green, R., Bartel, D.P., and Szostak, J.W. 1989. The guanosine binding site of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Nature 342: 391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, H. and Engberg, J. 1985. Functional intron+ and intron− rDNA in the same macronucleus of the ciliate Tetrahymena pigmentosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 825: 30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, N., Hellung-Larsen, P., and Engberg, J. 1985. Small nuclear RNAs in the ciliate Tetrahymena. Nucleic Acids Res. 13: 4203–4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R. and Herschlag, D. 1999. Specificity from steric restrictions in the guanosine binding pocket of a group I ribozyme. RNA 5: 158–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.J. and Herrin, D.L. 1991. In vitro self-splicing reactions of the chloroplast group I intron Cr.LSU from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and in vivo manipulation via gene-replacement. Nucleic Acids Res. 19: 6611–6618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vader, A. 1998. ``Nuclear group I introns in myxomycetes: Organization, expression and evolution.'' Ph.D. thesis, University of Tromsø, Norway.

- Vader, A., Nielsen, H., and Johansen, S. 1999. In vivo expression of the nucleolar group I intron-encoded I-DirI homing endonuclease involves the removal of a spliceosomal intron. EMBO J. 18: 1003–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vader, A., Johansen, S., and Nielsen, H. 2002. The group I-like ribozyme DiGIR1 mediates alternative processing of pre-rRNA transcripts in Didymium iridis. Eur. J. Biochem. 269: 5804–5812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson, S.A. and Cech, T.R. 1989. Reverse self-splicing of the Tetrahymena group I intron: Implication for the directionality of splicing and for intron transposition. Cell 57: 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrinkar, P.P. and Sullenger, B.A. 1998. Probing the interplay between the two steps of group I intron splicing: Competition of exogenous guanosine with omega G. Biochemistry 37: 18056–18063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaug, A.J., Grabowski, P.J., and Cech, T.R. 1983. Autocatalytic cyclization of an excised intervening sequence RNA is a cleavage-ligation reaction. Nature 301: 578–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]