Abstract

RNA sequences that conform to the consensus sequence of 5′ splice sites but are not used for splicing occur frequently in protein coding genes. Mutational analyses have shown that suppression of splicing at such latent sites may be dictated by the necessity to maintain an open reading frame in the mRNA. Here we show that stop codon frequency in introns having latent 5′ splice sites is significantly greater than that of introns lacking such sites and significantly greater than the expected occurrence by chance alone. Both observations suggest the occurrence of a general mechanism that recognizes the mRNA reading frame in the context of pre-mRNA.

Keywords: latent 5′ splice sites, splice site selection, stop codons, suppression of splicing (SOS), translatability

In a recent paper, Zhang et al. (2003) presented a computational analysis that attempted to challenge the idea that the translatability of an exon can influence its splicing. This idea has been recently supported by a number of studies: Wang et al. (2002) and Mendell et al. (2002) demonstrated the occurrence of nonsense-associated alternative splicing in mutated genes, and a study from our laboratory (Li et al. 2002) demonstrated that splicing at intronic latent 5′ splice sites is suppressed in wild-type genes when in-frame stop codons occur between the latent and the upstream normal (authentic) 5′ splice site.

Latent 5′ splice sites are defined as sequences that conform to the canonical 5′ splice site consensus sequence but, normally, are not used for splicing. Latent sites appear to be highly abundant in the genome, particularly in introns of protein-coding genes (see below). To explain the phenomenon of suppression of splicing (SOS) at latent 5′ splice sites, we proposed that the necessity to maintain the translatability of mRNAs, by avoiding the inclusion of premature termination codons in them, could serve as a criterion that differentiates normal 5′ splice sites from latent ones (Miriami et al. 1994). We substantiated this proposal by showing, in two gene systems, that an intronic latent 5′ splice site can be activated if all upstream stop codons, which are in the reading frame of the upstream exon, are eliminated by point or frame-shift mutations (Li et al. 2002). We also validated, by three criteria, the generality of the translatability hypothesis in a computerized genomic survey of a human database of 2206 introns, 1496 of which contain a total of 10,490 latent 5′ splice sites and 710 of which are devoid of such sites. First, of the 1496 introns with latent 5′ splice sites, 1359 (90.8%) have at least one in-frame stop codon upstream of the most 3′ latent site. Second, in-frame stop codons occur upstream of 10,045 (95.8%) of the 10,490 latent 5′ splice sites. Third, the density of in-frame stop codons in the 1496 introns with latent 5′ splice sites is significantly higher than that in the 710 introns devoid of latent sites (0.0484 versus 0.0338 per effective number of codons; P < 0.001; Miriami et al. 2002).

Zhang et al. (2003) challenged the translatability concept because their genomic analysis of pseudo exons showed that the proportion of such exons that have at least one in-frame stop codon was not significantly different from that occurring merely by chance. Because our analyses dealt with latent 5′ splice sites (Miriami et al. 2002), but not with pseudo exons, this response is confined to the former. Nonetheless, we would like to comment that the number of known cases of pseudo exon inclusion is rather limited, and the requirements for pseudo exon inclusion are more complex than those required for latent splicing. These requirements include the presence of 5′ and 3′ splice sites, a branch site, and also the presence of exonic enhancers and probably the lack of intronic silencers. Furthermore, it is not known what percentage of pseudo exons, not yet included in the human EST database, are potential alternative exons.

Based on their analysis of extended (latent) exons, which result from splicing at intronic latent 5′ splice sites, Zhang et al. (2003) also claim that the occurrence of in-frame stop codons in such latent exons is not different from that occurring by chance. Their analysis, however, is subject to a serious drawback arising from the fact that their database had to be limited to short sequences, because the probability of the occurrence of stop codons by chance in long sequences approaches unity. Thus, limiting the size of extended exons to 100 nt excluded from the analyses many introns like that of the CAD gene, where a latent 5′ splice site is located 125 nt downstream from the authentic exon with four in-frame stop codons between them. Likewise, an intron of the IDUA gene, having a latent 5′ splice site located 235 nt downstream from the authentic one, was also excluded from this kind of analysis. Notably, mutational analyses of transfected minigenes derived from the CAD and IDUA genes showed that latent splicing, resulting in an extended exon, indeed occurred when all in-frame stop codons were removed (Li et al. 2002).

Notwithstanding the above argument, there appears to be a graphing error in Figure 1B ▶ of Zhang et al. (2003), which may have led these authors to a wrong conclusion. Zhang et al. (2003) measured the occurrence of nonsense codons as a function of the distance between an authentic 5′ splice site and a latent 5′ splice site situated ≤100 nt downstream of that site for 1164 intron sequences. Then they showed that these data points fall on or close (below and above) to a curve that represents the results expected by chance. From this observation they concluded that the proportion of intervening sequences having at least one in-frame nonsense codon was not greater than that expected by chance, meaning that translatability does not affect splicing. The problem is that this curve was erroneously drawn too high. Had they drawn it correctly, they would have noticed that all but two of their data points fall well above the curve representing the results expected by chance (for details, see http://www.weizmann.ac.il/~cosper/suppinfo/Miriami.pdf). This realization would have led them to conclude that translatability does affect splicing.

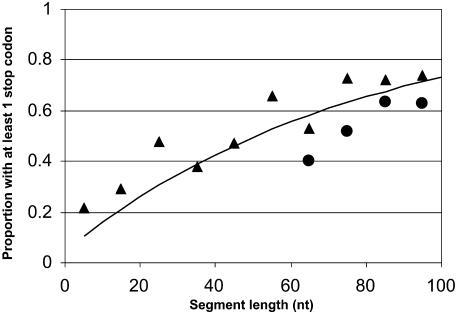

FIGURE 1.

The occurrence of in-frame stop codons in 100-nt downstream flanks of authentic exons. The line represents the expected occurrence of at least one stop codon by chance alone, using a binomial probability distribution. The parameters were derived from the 2311 sequences in our database: 0.1160 as the probability of an in-frame stop codon in the intron region +1 to +6; 0.0375 as the probability of an in-frame stop codon per triplet in the intron region +7 to +100. (Triangles) observed frequency in introns having latent 5′ splice sites; (circles) observed frequency in introns without latent sites. The X-axis represents the length of segments, in nucleotides, starting from the authentic 5′ splice junction.

To strengthen the above critique, we applied the criteria used by Zhang et al. (2003) to our database. First, we calculated the overall frequency of in-frame stop codons in the downstream 100-nt flank of the authentic 5′ splice sites of all 2311 introns in our data set. Like these authors, we considered the intron flank to be made up of two components: (1) the authentic 5′ splice site itself (+1 to +6), which has a high probability of harboring a nonsense codon due to the consensus CAG/GURAGU (“/” denotes the 5′ splice junction, R is A or G), which carries a URA triplet at positions +2 to +4; and (2) the remaining sequence. Among the 2311 5′ splice sites in our database, we found 268 that harbor an in-frame stop codon. Hence, the probability of finding an in-frame stop codon in the first intronic 6 nt is 268/2311 = 0.1160. The probability of finding an in-frame stop codon in the remaining intron region (+7 to +100 nt) was found to be 0.0375 per triplet, which is almost identical to the value reported by Zhang et al. (2003). As pointed out by these authors, this value is smaller than the value expected on a random basis (3/64 = 0.0469), reflecting the nonrandom nature of sequences flanking exons (Nussinov 1989; Engelbrecht et al. 1992). Hence, the probability of a segment of length L nt (L ≤ 100), starting from the authentic 5′ splice junction, to contain at least one stop codon is 1 − [(1 − 0.1160) × (1 − 0.0375)(L−6)/3], and is presented by the solid line in Figure 1 ▶. Next, we portrayed the observed data points of the proportion of introns having at least one in-frame stop codon as a function of intron length downstream of the authentic 5′ splice junction (introns were grouped in windows of 10 nt). For introns having latent 5′ splice sites, we found that this proportion is considerably higher than expected (Fig. 1 ▶, triangles). Importantly, however, for introns without latent 5′ splice sites, the observed proportion of introns having at least one in-frame stop codon was considerably lower than expected (Fig. 1 ▶, circles). The findings presented here, in addition to our previous mutational and computational analyses, reinforce the conclusion that intronic in-frame stop codons act in a general way in suppressing splicing at downstream latent 5′ splice sites, thereby maintaining an open reading frame in mRNAs.

It is therefore not surprising that when Zhang et al. (2003) calculated, for their database, the density of stop codons in introns with and without latent 5′ splice sites, they obtained the same result as we did in Miriami et al. (2002), namely, a significant difference in stop codon density between introns with and without latent 5′ splice sites. However, these authors interpret this result differently on the premise that introns lacking latent splice sites are necessarily short, whereas introns with such sites are much longer. Indeed, the density of stop codons is somewhat smaller in shorter introns (looking at our database, we found a positive correlation of 0.0935 between the length of the intron and the density of stop codons among the 1496 introns that have latent 5′ splice sites). Because the average length of the 710 introns without latent 5′ splice sites is smaller than the average length of the 1496 introns that have such sites (206.6 nt versus 1642.7 nt), one might expect the density of stop codons to be higher in the second group than in the first group. However, if we consider only the shortest introns that have latent 5′ splice sites, so that their average length is similar to that of the introns that do not have latent 5′ splice sites, we still get a highly significant difference. Thus, for introns that are not longer than 350 nt (n = 345), the average length is 204.5 nt and the density of stop codons is 0.04111 ± 0.00154 stop codons per effective number of codons (estimate ± standard error), whereas for introns that do not have latent 5′ splice sites, the estimate of the density is only 0.03382 ± 0.00110. This difference is highly significant (P < 0.001). For introns in which the distance between the authentic 5′ splice site and the 3′ most latent site is not longer than 500 nt (n = 718), the average length is 206.5 nt and the density of stop codons is 0.04156 ± 0.00114 stop codons per effective number of codons. Again, this value is significantly larger than that for introns lacking latent 5′ splice sites (P < 0.001). Finally, we calculated the density of stop codons for the sequence between the authentic 5′ splice site and the nearest latent site in the downstream intron. From the point of view of translatability, this sequence is the shortest relevant sequence for each of the 1496 introns with latent 5′ splice sites (note that there are 10,490 latent sites in these 1496 introns). The average length of the sequences in this group is 206.3 nt. Here again, the density of stop codons per effective number of codons is 0.04221 ± 0.00081, which is significantly larger than the value of 0.03382 ± 0.00110 obtained for introns that do not have a latent site (P < 0.001).

Zhang et al. (2003) argue, however, that in their data set, the lower density of stop codons in introns lacking latent 5′ splice sites can be correlated with the GC richness of these introns (55%) compared to all introns in the data set (49%). They argue that because stop codons are AT-rich, their density would be expected to be lower in GC-rich introns. This argument is not consistent with the results we obtain in our data set. For example, the density of stop codons in the subgroup of introns with latent sites, whose length is ≤350 nt, is 0.04111 stop codons per effective number of codons, whereas that in the introns that do not have latent 5′ splice sites is significantly smaller (0.03382 ± 0.00110). On the other hand, the AT content of these groups of introns is 47.1% and 45.6%, respectively. Furthermore, the density of stop codons in the three subgroups of introns with latent sites described above is rather similar (0.04111, 0.04156, and 0.04221), although their AT content varies considerably (47.1%, 50.9%, and 50.1%, respectively). The possibility that stop-codon density and AT content may not be mutually dependent is more profoundly manifested in the individual introns of the CAD and IDUA genes, for which we have proven the translatability concept by mutational analyses (Li et al. 2002). The CAD intron has four in-frame stop codons in the segment of 125 nt between the authentic and latent 5′ splice sites (stop-codon density 0.096), whose AT content is only 36%. Likewise, the IDUA intron has only one in-frame stop codon in the segment of 235 nt between the authentic and latent 5′ splice sites (stop-codon density 0.0128), whose AT content is 25%. We can therefore conclude that the differences in stop-codon density between introns with and without latent sites cannot be attributed to the differences in their AT content. The density of the out-of-frame stop codons, however, did not differ from that of the in-frame stop codons in either set. This apparent inconsistency may be attributed to the relatively high abundance (36%) of human exons that are translatable in multiple reading frames (Clark & Thanaraj 2002), which necessitates the maintenance of translatability in all frames. An alternative, more speculative, explanation arises from recent experiments done in our laboratory (G. Yahalom, C. Wachtel, J. Sperling, and R. Sperling, unpubl.) showing that start codons and stop codons in more than one frame affect latent splicing. We therefore believe that our analyses support the notion that translatability plays a role in 5′ splice site selection.

How important is translatability? The survey of the database used for our analysis indicated that more than 90% of the 446 genes contain at least one intron with a latent 5′ splice site, and many introns contain multiple latent sites. The high abundance of latent sites in the genome necessitates a general mechanism that can discriminate latent sites from authentic ones. Our survey predicts that translatability can account for SOS in 90.8% (1359 out of 1496) of the introns that have latent 5′ splice sites. Furthermore, the remaining 10% contain introns that could be candidates for alternative splicing, and introns in which latent splicing results in frame shifts that introduce stop codons in downstream exons. Evidently, translatability belongs to a number of general mechanisms that direct 5′ splice site selection. Yet, its relative weight in this process cannot be estimated presently. It is clear, however, that the strength of the translatability concept resides also in its ability to provide a working platform for the design of experiments that uncover mechanisms and components that are involved in the regulation of splicing. The experiments done so far, demonstrating SOS in wild-type genes, reinforce this concept and its general use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation (R.S.) and The Lady Davis Fellowship Fund (E.M.).

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5112704.

REFERENCES

- Clark, F., and Thanaraj, T.A. 2002. Categorization and characterization of transcript-confirmed constitutively and alternatively spliced introns and exons from human. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11: 451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht, J., Knudsen, S., and Brunak, S. 1992. G+C-rich tract in 5′ end of human introns. J. Mol. Biol. 227: 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, B., Wachtel, C., Miriami, E., Yahalom, G., Friedlander, G., Sharon, G., Sperling, R., and Sperling, J. 2002. Stop codons affect 5′ splice site selection by surveillance of splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 5277–5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell, J.T., ap Rhys, C.M.J., and Dietz, H.C. 2002. Separable roles for rent1/hUpf1 in altered splicing and decay of nonsense transcripts. Science 298: 419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miriami, E., Sperling, J., and Sperling, R. 1994. Heat shock affects 5′ splice site selection, cleavage and ligation of CAD pre-mRNA in hamster cells, but not its packaging in lnRNP particles. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 3084–3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miriami, E., Motro, U., Sperling, J., and Sperling, R. 2002. Conservation of an open-reading frame as an element affecting 5′ splice site selection. J. Struct. Biol. 140: 116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussinov, R. 1989. Conserved signals around the 5′ splice sites in eukaryotic nuclear precursor mRNAs: G-runs are frequent in the introns and C in the exons near both 5′ and 3′ splice sites. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 6: 985–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Hamilton, J.I., Carter, M.S., Li, S., and Wilkinson, M.F. 2002. Alternatively spliced TCR mRNA induced by disruption of reading frame. Science 297: 108–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Lee, J., and Chasin, L.A. 2003. The effect of nonsense codons on splicing: A genomic analysis. RNA 9: 637–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]