Abstract

A number of mitochondrial proteins have been identified in Leishmania sp. and Trypanosoma brucei that may be involved in U-insertion/deletion RNA editing. Only a few of these have yet been characterized sufficiently to be able to assign functional names for the proteins in both species, and most have been denoted by a variety of species-specific and laboratory-specific operational names, leading to a terminology confusion both within and outside of this field. In this review, we summarize the present status of our knowledge of the orthologous and unique putative editing proteins in both species and the functional motifs identified by sequence analysis and by experimentation. An online Supplemental sequence database (http://164.67.60.200/proteins/protsmini1.asp) is also provided as a research resource.

Keywords: editing, trypanosomes, RNA, L-complex

INTRODUCTION

The identification of proteins putatively involved in U-insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria has progressed very rapidly recently, owing to the application of mass spectrometry gene identification methods to components of macromolecular editing complexes isolated by a variety of methods, combined with the availability of partial genome databases for both Leishmania major and Trypanosoma brucei (http://www.genedb.org/). Our 2003 review (Simpson et al. 2003) is already considerably out of date.

Putative editing proteins have been identified both by direct biochemical isolations targeted for known enzymatic or RNA binding activities, and by sequencing of protein components of macromolecular complexes active in in vitro editing. Possibly functional motifs have been identified by sequence analysis but only confirmed by analysis of recombinant proteins in a few cases. Evidence for an involvement in editing has been obtained for several of these proteins by down-regulation of expression using conditional gene disruptions and RNA interference, but even this evidence is frequently difficult to interpret.

THE 20S “EDITOSOME”

A full cycle, although fairly inefficient, of gRNA-dependent in vitro editing activity that sedimented at approximately 20S in glycerol gradients was detected in mitochondrial extracts from procyclic T. brucei (Corell et al. 1996; Kable et al. 1996; Seiwert et al. 1996). Enrichment of this editing activity in the Sollner-Webb laboratory using sequential Q Sepharose and DNA cellulose column fractionations of mitochondrial extract led to a complex reported to contain seven major polypeptides; this sedimented at approximately 20S in glycerol gradients and migrated as a single band in a native gel (Rusché et al. 1997). This preparation was capable of both full round U-insertion and U-deletion editing at one or two sites using synthetic pre-edited A6 mRNA and the cognate gRNA, and the efficiency of in vitro editing could be substantially increased by modifications of the mRNA and gRNA sequences (Cruz-Reyes and Sollner-Webb 1996; Cruz-Reyes et al. 1998, 2001, 2002). The polypeptides were operationally labeled Bands I–VII. Bands IV and V proved to be the REL1 and REL2 RNA ligases (Rusché et al. 2001), which had been functionally identified previously as adenylatable proteins (Sabatini and Hajduk 1995; Peris et al. 1997) and Band III, a zinc finger-containing protein (Huang et al. 2002). Down-regulation of Band III by RNAi was lethal and affected in vivo endonucleolytic cleavage and RNA ligation but not addition or removal of uridines. Recognizable nuclease motifs are absent in the Band III protein, indicating these are indirect effects, consistent with the decrease of the sedimentation value of the entire complex (Huang et al. 2002). The notion that these seven proteins represented the complete set of proteins required for editing (Rusché et al. 1997) has evolved into the realization that a variety of additional components, which are most likely present in substoichiometric amounts or interact transiently, are also required (Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Panigrahi et al. 2003a). For example, the RET2 TUTase required for U-insertion editing (see below) is not one of these seven polypeptides (B. Sollner-Webb, pers. comm.).

A similar fractionation procedure of in vitro editing activity in the Stuart laboratory involving sequential SP Sepharose, Q Sepharose, and Superose 6 chromatography of mitochondrial extract led to a product that contained more than 20 major polypeptides (Corell et al. 1996; Panigrahi et al. 2001a,b, 2003b). A product of a similar complexity was isolated by immunoprecipitation of the 20S region from a glycerol gradient of mitochondrial extract using an antibody against TbMP63, one of the protein components of the core complex (Sollner-Webb lab Band III). Several nonmitochondrial and mitochondrial metabolic or structural proteins were, however, also identified by mass spectrometric analysis of tryptic peptides derived from the biochemically purified material and the monoclonal antibody affinity-purified material (Panigrahi et al. 2003a), some of which represented major stained bands in SDS-PAGE, most likely caused by high abundance of these proteins in the mitochondrial cell fractions used as starting material.

Approximately 16 polypeptides with mitochondrial targeting signals were identified that appeared by one or more criteria to represent possible components of the editing machinery (see Table 1 ▶). These proteins have been given the operational designation of TbMPx in the Stuart laboratory, where x represents the calculated molecular weight of the mitochondrial pre-protein. The criteria included either cosedimentation in the 20S region in glycerol gradients, coimmunoprecipitation by antibodies against specific proteins demonstrated to be essential for editing, double affinity purification using TAP-tagged proteins, or demonstration of an inhibition of RNA editing by conditional down-regulation of expression in vivo. The genetic method is the most definitive especially because major nonediting protein contaminants were present in the biochemically purified and in the antibody-purified fractions. TbMP123, MP103, MP100, MP99, MP90, MP67, MP61, and MP24 represent proteins with mitochondrial signal sequences that were identified by mass spectrometry analysis of purified editing complexes but for which no definite evidence for inclusion in the editing complex was reported (Table 1 ▶).

TABLE 1.

Putative editing-related proteins in Leishmania and T. brucei

| Operational names | |||||||||||||

| Leishmania | T. brucei | Possible function | Effect of down-regulation on editing activity | ||||||||||

| Simpson lab | Stuart lab | Sollner-Webb lab | Functional names | Motifs | Putative | Exptl. verified | L-complex | GP-complex | MRP-complex | In vivo | In vitro | % ID of Lm and Tb | Ref |

| LC-1 | MP81 | Band II | ZnF_C2H2 | Structural scaffold | Interacts with RET2 and REL2 | TAP, IP, CC | Lethal, A6, ND7, Cyb | U-insertion | 27 | Panigrahi et al. 2001b; Aphasizhev et al. 2003a | |||

| LC-2 | MP100 | Exo_endo_phos | 3′–5′ exonucl. of mRNA | TAP, IP, CC | 39 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||

| LC-3 | MP99 | Exo_endo_phos | 3′–5′ exonucl. of mRNA | TAP, IP, CC | 25 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||

| LC-4 | MP63 | Band III | ZnF_C2H2 | Structural scaffold | TAP, IP, CC | Lethal | mRNA cleavage and ligation | 36 | Panigrahi et al. 2001b; Aphasizhev et al. 2003a | ||||

| LC-5 | MP46 | ZnF_NFX | RNA binding | TAP, IP, CC | 19 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||

| LC-6a | MP61 | RNase III | Cleavage of mRNA | TAP, IP, CC | 38 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||

| LC-6b | MP57 | RET2 | 3′-TUTase | Addition of Us at editing site | Recomb. protein TUTase activity | TAP, IP, CC | Lethal, ND8, COIII Cyb, COII | U-insertion | 67 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Ernst et al. 2003 | |||

| LC-7a | MP52 | Band IV | REL1 | Ligase | Ligation of mRNA fragments | Recomb. protein ligase activity | TAP, IP, CC | Lethal, A6, ND7, RPS12 | 65 | McManus et al. 2001; Panigrahi et al. 2001a; Rusché et al. 2001; Schnaufer et al. 2001; Aphasizhev et al. 2003a | |||

| LC-7b | MP42 | Band VI | ZnF_C2H2 | Structural scaffold | TAP, IP, CC | 42 | Panigrahi et al. 2001b; Aphasizhev et al. 2003a | ||||||

| LC-7c | — | TAP, CS | 11 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003a | |||||||||

| LC-8 | MP44 | RNase III | Cleavage of mRNA | TAP, IP, CC | Lethal, ND7, A6, ND4, RPS12 | Disrupts L-complex | 41 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||

| LC-9 | MP48 | Band V | REL2 | Ligase | Ligation of mRNA fragments | Recomb. protein ligase activity | TAP, IP, CC | No phenotype | No effect | 64 | McManus et al. 2001; Panigrahi et al. 2001a; Aphasizhev et al. 2003a | ||

| LC-10 | — | TAP | Aphasizhev et al. 2003a | ||||||||||

| LC-11 | MP18 | Band VII | SSB | Binds RNA | TAP, IP, CC | 44 | Panigrahi et al. 2001b; Aphasizhev et al. 2003a | ||||||

| MP121 | IP, CC | Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||||||

| Lm MP90 | MP90 | RNase III | Cleavage of mRNA | IP, CC | 38 | Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||

| MP103 | IP, CC | Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||||||

| Lm MP67 | MP67 | RNase III | Cleavage of mRNA | IP, CC | 24 | Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||

| MP24 | IP, CC | Panigrahi et al. 2003b | |||||||||||

| Lm RGGm | TbRGGm- | RRM | RNA binding | IP | 57 | Vanhamme et al. 1998; Panigrahi et al. 2003a | |||||||

| REAP-1 | mRNA binding | Madison-Antenucci et al. 1998 | |||||||||||

| RBP16 | Cold shock domain | RNA binding | Letha, Cyb, COI, ND4 | 72 | Pelletier and Read 2003 | ||||||||

| Lm mHel61 | mHEl62 | DEAD box | Helicase? | Slow growth, inhibited | No effect | 48 | Missel et al. 1997 | ||||||

| LtTUTase | TbTUTase | RET1 | 3′-TUTase | 3′-U addition to gRNAs | Recomb. protein TUTase activity | CC | IA, TAP | Lethal, ND7, ND8, COIII, Cyb, MURF2 | U-insertion, length of 3′-oligo(U) tail | 38 | Aphasizhev et al. 2002 | ||

| Ltp26 | gBP21 | MRP1 | gRNA-mRNA binding | Recomb. protein RNA annealing | TAP, CC | 45 | Koller et al. 1997; Aphasizhev et al. 2003b | ||||||

| Ltp28 | gBP25 | MRP2 | gRNA-mRNA binding | Recomb. protein RNA annealing | TAP, CC | 43 | Blom et al. 2001; Aphasizhev et al. 2003b | ||||||

| AP1 | MRP-AP1 | TAP | 48 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003b | |||||||||

| AP2 | MRP-AP2 | mre11_DNA_bind | RNA binding | TAP | 59 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003b | |||||||

| AP3 | MRP-AP3 | NUDIX | Hydrolase | TAP | 42 | Aphasizhev et al. 2003b | |||||||

Abbreviations: IP, protein detected in immunoaffinity-purified material; TAP, protein detected in material isolated by tandem affinity purification; CC, protein detected in material purified by column chromatography and/or sedimentation; ID, identical amino acids.

The TbMP52 and TbMP48 proteins (the Sollner-Webb laboratory Bands IV and V) were identified as the two mitochondrial RNA ligases (Sabatini and Hajduk 1995; McManus et al. 2001) and were designated REL1 (RNA Editing Ligase 1) and REL2 (McManus et al. 2001; Panigrahi et al. 2001a; Rusché et al. 2001; Schnaufer et al. 2001). Down-regulation of REL1 was lethal and inhibited editing, but down-regulation of REL2 (Drozdz et al. 2002; Stuart et al. 2002; Gao and Simpson 2003) had no effect on cell growth. Down-regulation of TbMP81 and Band III (= TbMP63) expression by conditional RNAi inhibited in vivo editing but not transcription or mRNA stability.

The TbMP57 protein showed a nucleotidyltransferase motif and poly(A) polymerase-associated motifs, and recombinant protein immunoprecipitated from a reticulocyte transcription–translation system (Ernst et al. 2003) or expressed in Leishmania tarentolae as a TAP-tagged cytosolic protein by removal of the mitochondrial signal peptide (Aphasizhev et al. 2003c) both exhibited a 3′-TUTase activity that added mainly a single U residue to the 3′-OH of a single-stranded RNA substrate. This protein has been designated RET2 (RNA Editing TUTase 2; Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Ernst et al. 2003), as suggested by K. Stuart (pers. comm.). Down-regulation of RET2 in procyclic T. brucei was lethal and led to a complete inhibition of U-insertion precleaved in vitro editing and no effect on U-deletion editing or on the length of the 3′-oligo[U] tails of the gRNAs, whereas down-regulation of RET1 expression produced a small effect on in vitro U-insertion editing and a large effect on the length distribution of the 3′-oligo[U] tails of gRNAs (Aphasizhev et al. 2003c). It was concluded that RET2 is an integral part of a core editing complex and is responsible for the addition of Us to the editing site and RET1 is responsible for the 3′ addition of Us to the gRNAs (Aphasizhev et al. 2003c).

One protein was identified that was homologous to the mitochondrial RNA-binding protein, TcRGGm, and was therefore designated TbRGG1, but there is no evidence that this is a component of an isolated editing complex (Vanhamme et al. 1998; Panigrahi et al. 2003a).

The difference in the number of polypeptides obtained in these two laboratories is most likely due to technical differences in isolation and detection methodologies and to differential stability of the complex components. In both cases, the final preparations showed both U-insertion and U-deletion in vitro editing activity. There is clearly a fairly stable macromolecular complex composed of ~16 proteins sedimenting at approximately 20S in glycerol gradients, but it may be premature to designate this as the “editosome” (Panigrahi et al. 2003a) because work in the L. tarentolae system discussed below has indicated a higher complexity of interacting components of the editing machinery required for functional editing (Aphasizhev et al. 2003a,b).

THE L-COMPLEX

The ligase-containing complex (L-complex) was first identified as a high-molecular-weight band in native gels of L. tarentolae and T. brucei mitochondrial extracts that could be labeled with [α-32P]ATP (Sabatini and Hajduk 1995; Peris et al. 1997; Rusché et al. 1997) because of the presence of the two adenylatable RNA ligases, REL1 and REL2 (Sabatini and Hajduk 1995). This complex sedimented in glycerol gradients in a broad region from 20S to 25S but as a single band in a native gel and is almost certainly identical to the “editosome” complexes isolated from T. brucei discussed above. The L-complex was isolated from L. tarentolae by the TAP procedure using a REL1 fusion protein (Aphasizhev et al. 2003a). The purified L-complex sedimented as a single homogeneous adenylatable 20S particle both in gradients and in native gels. The isolated material showed precleaved U-insertion and U-deletion editing activity. Substoichiometric amounts of RET1 and MRP1 and MRP2 were also present in the final preparation, indicating a low-affinity interaction of the L-complex with the MRP-complex, the GP-complex, and gRNA (see below).

The gradient-isolated TAP-tagged 20S L-complex was composed of 13–16 bands in an SDS gel in approximate stoichiometric amounts (Aphasizhev et al. 2003a). The absence of contamination with abundant mitochondrial metabolic enzymes was shown by probing with antiserum for glutamate dehydrogenase. Substoichiometric amounts of RET1 and the MRP1,2 proteins could be identified by Western analysis. So far, 15 polypeptides have been identified by MS/MS analysis of tryptic peptides from gel-isolated stained bands. All except LC-10 have orthologs in the T. brucei database, and orthologs to MP90 and MP67 were identified in the L. major database. LC-6b (MP57) was shown to be a 3′-TUTase and was labeled RET2, as mentioned above.

Functional motifs in the L-complex proteins

All identified Leishmania editing proteins and the orthologs in T. brucei are shown in Table 1 ▶, together with the operational designations and the functional gene names if assigned. The apparent absences of LC-10 in T. brucei and MP90, MP103, and MP121 in Leishmania are probably due to database gaps rather than species-specific differences. All sequences in FastA format can be obtained from the online spreadsheet at http://164.67.60.200/proteins/protsmini1. asp. Alignments of orthologs from Leishmania and Trypanosoma with identified motifs indicated are also presented in the online spreadsheet as pdf files.

The presence of the Leishmania LC-proteins in the TAP-affinity isolated complex in approximately stoichiometric yields (Aphasizhev et al. 2003a) indicates that these are, indeed, integral components of the L-complex, and that the orthologs in T. brucei are also L-complex components in that species.

RNA and/or protein-binding motifs

LC-1 (MP81), LC-4 (MP63), LC-7b (MP42), and LC-5 (MP46) have zinc finger motifs, which could be nucleic acid or protein-binding. LC-11 (MP18) also has an SSB-like single-strand-binding motif (Fig. 1 ▶). SSB-like motifs can be recognized in LC-7b (MP42) and LC-10 by alignment of the LC-11 (MP18) SSB motif sequence, as indicated in Figure 1 ▶. Only the zinc finger motifs in LC-4 (MP63) have so far been experimentally shown to have a biochemical function in protein–protein interactions (X. Kang and L. Simpson, unpubl.). Possible RNA-binding functions of these motifs remain to be experimentally demonstrated.

FIGURE 1.

L-complex proteins with protein- and nucleic acid-binding motifs. The locations of the tryptic peptide sequences used for the L. major gene identifications are indicated by triangles in this and the following figures. All motif identifications in this and the following figures were performed using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and PFAM (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/index.shtml). The e-values are indicated in parentheses. Mitochondrial target signals were identified by MitoProt (http://www.mips.biochem.mpg.de/cgi-bin/proj/medgen/mitofilter), SMART, or SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). The probabilities from MitoProt are given above the figure. Note that the motifs in LC-10 and LC-7b were identified by similarity with the SSB motif in LC-11. All sequences were obtained from the GeneDB Leishmania major and Trypanosoma brucei databases.

RNase III motifs

Three proteins with RNase III motifs were identified from Leishmania major and T. brucei (Fig. 2 ▶). RNase III enzymes degrade double-stranded RNA and are involved in rRNA processing and degradation of some mRNAs. The presence of an RNase III-like motif in LC-8 (MP44) was only detected by alignment of the LC-6a (MP61) RNase III motif sequence (Fig. 2 ▶). There is as yet no biochemical evidence for enzymatic activity of these proteins. A possible function is the gRNA-mediated cleavage of mRNA at editing sites.

FIGURE 2.

L-complex proteins with RNase III motifs. Note that the motif in LC-8 was identified by similarity with the RNase III motif in LC-6a. The L. major homologs to the T. brucei MP90 and MP67 were identified by database mining.

Exonuclease–endonuclease–phosphatase motifs

There are two L-complex proteins, LC-2 (MP100) and Tb MP99, with exonuclease–endonuclease–phosphatase motifs (Fig. 3 ▶). The L. major LC-3 protein is clearly an ortholog to MP99 but, interestingly, lacks most of the motif sequence.

FIGURE 3.

L-complex proteins with nuclease motifs. The LC-3 protein identified by mass spectrometry lacks most of the Exo_endo_phos motif present in MP99, but otherwise is very similar.

3′-TUTase motif

The L-complex LC-6b (MP57; Aphasizhev et al. 2003a; Ernst et al. 2003) has a nucleotidyltransferase motif separated between the second and third catalytic aspartates by a stretch of amino acids that is not found in other nucleotidyltransferase proteins, as exemplified by the RET1 TUTase (Fig. 4 ▶; Aphasizhev et al. 2002). There are also poly(A) polymerase-associated motifs. This is the ortholog of RET2 in T. brucei, which has been expressed and shown to add mainly a single U residue to the 3′-end of RNA substrates (Aphasizhev et al. 2003c; Ernst et al. 2003).

FIGURE 4.

The L. major L-complex RET2 3′-TUTase. The homolog in T. brucei was identified by database searching (Aphasizhev et al. 2002) and has been characterized experimentally (Ernst et al. 2003).

Ligase motifs

The five motifs in the REL1 and REL2 proteins indicated in Figures 5 ▶ and 6 ▶ are conserved among both DNA and RNA ligases (McManus et al. 2001; Ho and Shuman 2002). The localizations of the lysine residues that covalently bind AMP were also determined experimentally (Huang et al. 2001). Ligase activities of recombinant TbREL1 and REL2 expressed in an Escherichia coli system (McManus et al. 2001; Rusché et al. 2001), TbREL1 and TbREL2 expressed in a reticulocyte cell-free coupled transcription–translation system (Palazzo et al. 2003), and LtREL1 and LtREL2 expressed in the Baculovirus system (G. Gao and L. Simpson, unpubl.) have been demonstrated.

FIGURE 5.

The L-complex REL1 and REL2 RNA ligases. Five conserved ligase motifs (McManus et al. 2001) are indicated as is the location of the lysine residues that covalently bind AMP. These motifs can be recognized by multiple alignments with known ligase enzymes.

FIGURE 6.

Multiple alignments of portions of selected genes to illustrate the five conserved motifs in REL1 and RELL2 characteristic of DNA and RNA ligases (Shuman and Schwer 1995; Odell et al. 2000; McManus et al. 2001). (T3) Bacteriophage T3; (T7) bacteriophage T7; (Vac) Vaccinia virus; (At) Arabidopsis thaliana; (Mj) Methanocaldococcus jannaschii; (Cj) Campylobacter jejuni; (Sc) Saccharomyces cerevisiae; (Hu) human; (Ec) E. coli; (Ae) Aquifex aeolicus; (Mg) Mycoplasma genitalium; (T4) bacteriophage T4; (ChlV) Chlorella virus; (Tb) T. brucei; (Ce) Caenorhabditis elegans; (Lt) L. tarentolae; (Lm) L. major; (*) αPO4-binding residues; ($) metal-binding residues; (@) ribose O-binding residue; (#) residue binding to Arg; (&) adenine-binding residue.

THE MRP-COMPLEX

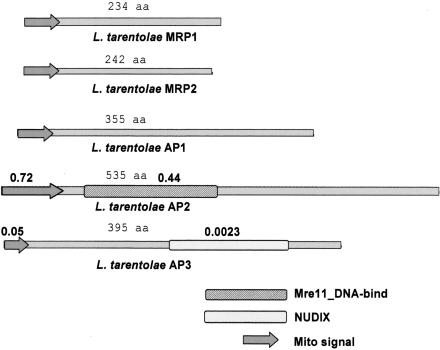

Two mitochondrial RNA-binding proteins (MRPs) from L. tarentolae, MRP-1, were shown to form a stable 100-kD complex (Aphasizhev et al. 2003b). These mitochondrial proteins, which were previously called Ltp26 and Lt28 (Aphasizhev et al. 2003b), are orthologs of TbgBP21 (Koller et al. 1997) and TbgBP25. We suggest the MRP designation instead of the original gBP (guide RNA binding protein) designation (Koller et al. 1997) because it is now known that these proteins bind RNA fairly nonspecifically (Aphasizhev et al. 2003b). TAP-isolation using an MRP-1 fusion protein was used to identify three additional interacting proteins, AP1, AP2, and AP3 (Fig. 7 ▶; Aphasizhev et al. 2003b). The TAP-isolated ~30S complex contained bound gRNA, and the native and recombinant MRP proteins from both species and the reconstituted 100-kD complex exhibited binding to both double- and single-stranded RNA and catalyzed RNA annealing (Muller et al. 2001; Aphasizhev et al. 2003b). We have designated this as the MRP-complex (Aphasizhev et al. 2003c). There is evidence that down-regulation of both MRP1 and MRP2 together affects viability of procyclic T. brucei (A. Simpson, R. Aphasizhev, I. Aphasizheva, and L. Simpson, unpubl.), but it remains to be demonstrated that the complex is involved in vivo with catalyzing the annealing of the gRNA and mRNA.

FIGURE 7.

MRP-complex proteins. The L. major MRP RNA-binding proteins and the three associated proteins (AP1, AP2, AP3) identified by double affinity isolation (Aphasizhev et al. 2003b) are indicated.

THE RET1-COMPLEX

A biochemical isolation of the major processive 3′-TUTase activity from L. tarentolae mitochondria yielded a 121-kD protein belonging to the nucleotidyltransferase superfamily (Fig. 8 ▶; Aphasizhev et al. 2002). The recombinant protein expressed in E. coli exhibited a U-specific 3′ transferase activity that added multiple Us to the 3′-OH of any single-stranded RNA. An involvement with RNA editing was evidenced by the correlation of down-regulation of expression with a decrease in editing in vivo. The homologous protein was identified in T. brucei, and it was shown that down-regulation of expression by RNAi led to a decrease in the average length of the 3′-oligo[U] tail of the gRNAs, indicating that the observed inhibition of editing in vivo was indirect. This protein was designated as RET1 (RNA Editing TUTase 1; Aphasizhev et al. 2003c), as suggested by K. Stuart (pers. comm.).

FIGURE 8.

RET1 proteins. The L. major and T. brucei RET1 TUTases are shown (Aphasizhev et al. 2002).

The majority of the protein was present as an ~500-kD tetramer, but a small portion was in the form of an ~700-kD complex that could be separated by ion exchange chromatography followed by sedimentation in a glycerol gradient or electrophoresis in a native gel. We have designated this as the RET1-complex (Aphasizhev et al. 2003c). It remains to be investigated whether a previously identified U-specific 3′–5′ exonuclease activity (Aphasizhev and Simpson 2001; Igo et al. 2002) is also associated with this complex. It is possible that the 700-kD complex is a breakdown product of a larger complex after ion exchange chromatography, but this must be further examined.

PROTEINS WITH POSSIBLE ROLES IN RNA EDITING

It should be noted that there are several additional mitochondrial RNA-binding proteins that interact with guide RNA and mRNA, such as Tb REAP-1 (Madison-Antenucci et al. 1998; Madison-Antenucci and Hajduk 2001), RPB16 (Hayman and Read 1999; Pelletier et al. 2000; Pelletier and Read 2003) and RGG1 (Fig. 9 ▶; Vanhamme et al. 1998). Down-regulation of Tb RBP16 by conditional RNA interference showed that this protein is required for viability. The effect on maxicircle transcripts was similar to that obtained by down-regulation of both MRP1 and MRP2 (R. Aphasizhev and L. Simpson, unpubl.). There was a 98% decrease in the abundance of edited Cyb transcripts with little effect on other edited RNAs, and a 80% decrease in never edited RNAs, COI and ND4. Immunoprecipitation of RBP16 coprecipitated gRNAs. But no stable interaction of RBP16 with purified editing complexes was observed (Stuart et al. 2002).

FIGURE 9.

Several proteins that may be involved in RNA editing. The L. major orthologs of the RNA-binding proteins, RBP16 and RGGm, and the putative helicase, mHel61, are shown. The T. brucei REAP-1 is shown because there is no ortholog of this protein in the L. major database.

No ortholog for REAP-1 has been found in Leishmania. REAP-1 was identified in a 20S editing complex by Western analysis and was shown to coimmunoprecipitate with anti-REL1 antiserum, indicating an interaction with the L-complex (Madison-Antenucci et al. 1998). It was also shown that REAP-1 interacted with the pre-edited region of mRNA (Madison-Antenucci and Hajduk 2001), indicating a possible role in the interaction of gRNA and mRNA.

TBRGG1 is a mitochondrial oligo[U]-binding protein that cosedimented with in vitro editing activity in glycerol gradients. Peptides from this protein were identified by mass spectrometry analysis of a partially purified editing complex (Panigrahi et al. 2003a).

Hel61 is a putative helicase because of the presence of a DEAD-box motif, but there is no biochemical evidence for this activity (Missel and Goringer 1994; Missel et al. 1995, 1997). A double allele knockout in procyclic trypanosomes led to a reduced growth rate and significantly lower amounts of edited mRNAs, with little effect on never edited RNAs. Re-expression of the gene from an ectopic copy restored the ability to synthesize edited mRNAs. However, no effect was observed on full round in vitro editing by mitochondrial extracts of the mHel61-null cells (Missel et al. 1997).

MODEL FOR HIGH-LEVEL ORGANIZATION OF EDITING COMPLEXES

Evidence that the MRP-complex, the RET1-complex, and the L-complex interact via RNA linkers

Evidence for interactions of the L. tarentolae L-complex with RET1 and MRP1/2 was obtained by showing that the L-complex could be immunodepleted from the 20S region and coimmunoprecipitated by anti-RET1 antibody and also by anti-MRP1/2 antibody (Aphasizhev et al. 2003a,b). RNase digestion of the L. tarentolae mitochondrial extract prior to glycerol gradient sedimentation eliminated the co-IP of the L-complex with anti-RET1 or anti-MRP1/2 antibodies, but had no effect on the S value or polypeptide composition of the L-complex. In addition, the RNase pretreated L-complex eluted from a native gel lacked any detectable in vitro U-insertion editing activity, implying that the presence of the substoichiometric RET1 and MRP1/2 components was essential for editing activity (R. Aphasizhev and L. Simpson, unpubl.). This, however, must be investigated further.

The MRP1/2 homologs in T. brucei, TbgBP21 and gPB25, also showed RNA-binding and RNA-annealing activities, and anti-gPB21 antibodies coimmunoprecipitated in vitro editing activity, ATP-labeled REL1 and REL2, and TUTase activity (Allen et al. 1998). This co-IP was sensitive to micrococcal nuclease digestion, indicating that it is likely that the GMR–RNP complex is also present in T. brucei and that it also interacts with the L-complex via RNA.

We propose that the core editing complex composed of ~16 proteins be designated the L-complex in both species, both for reasons of historical priority (Peris et al. 1997) and descriptiveness. The term “editosome” should be reserved for the complete functional editing supercomplex yet to be completely defined but consisting of at least the L-complex linked by RNA to the RET1-complex and the MRP-complex. A diagrammatic model for the organization of the three complexes is shown in Figure 10 ▶. It is, of course, also possible that there is no static supercomplex but that there is an dynamic functional interaction of multiple components. The analogy with the growing complexity of the spliceosome is striking (Rappsilber et al. 2002).

FIGURE 10.

Diagrammatic model for higher-order organization of editing complexes. The L-complex is shown as a dimer, for which the evidence is suggestive, and the three complexes are shown as interacting via RNA. The gRNA and mRNA indicated are the most likely candidates, but the existence of other RNA species has not been ruled out. The gRNA structure shown is taken from the model of Hermann et al. (1997).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a research grant to L.S. from the National Institutes of Health (AI09102). We thank all members of the Simpson laboratory for advice and discussion. We acknowledge the contribution of the parasite genome database sequencing centers, the Seattle Biomedical Research Institute, the Sanger Institute, and the Institute for Genomic Research for supplying the genomic sequences and for maintaining the relational databases (http://www.genedb.org/) that allowed the identification of most of these proteins.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5170704.

REFERENCES

- Allen, T.E., Heidmann, S., Reed, R., Myler, P.J., Goringer, H.U., and Stuart, K.D. 1998. Association of guide RNA binding protein gBP21 with active RNA editing complexes in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 6014–6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aphasizhev, R. and Simpson, L. 2001. Isolation and characterization of a U-specific 3′–5′ exonuclease from mitochondria of Leishmania tarentolae. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 21280–21284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aphasizhev, R., Sbicego, S., Peris, M., Jang, S.H., Aphasizheva, I., Simpson, A.M., Rivlin, A., and Simpson, L. 2002. Trypanosome mitochondrial 3′ terminal uridylyl transferase (TUTase): The key enzyme in U-insertion/deletion RNA editing. Cell 108: 637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aphasizhev, R., Aphasizheva, I., Nelson, R.E., Gao, G., Simpson, A.M., Kang, X., Falick, A.M., Sbicego, S., and Simpson, L. 2003a. Isolation of a U-insertion/deletion editing complex from Leishmania tarentolae mitochondria. EMBO J. 22: 913–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aphasizhev, R., Aphasizheva, I., Nelson, R.E., and Simpson, L. 2003b. A 100-kD complex of two RNA-binding proteins from mitochondria of Leishmania tarentolae catalyzes RNA annealing and interacts with several RNA editing components. RNA 9: 62–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aphasizhev, R., Aphasizheva, I., and Simpson, L. 2003c. A tale of two TUTases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 10617–10622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom, D., Burg, J., Breek, C.K., Speijer, D., Muijsers, A.O., and Benne, R. 2001. Cloning and characterization of two guide RNA-binding proteins from mitochondria of Crithida fasciculata: gBP27, a novel protein, and gBP29, the orthologue of Trypanosoma brucei gBP21. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 2950–2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corell, R.A., Read, L.K., Riley, G.R., Nellissery, J.K., Allen, T.E., Kable, M.L., Wachal, M.D., Seiwert, S.D., Myler, P.J., and Stuart, K.D. 1996. Complexes from Trypanosoma brucei that exhibit deletion editing and other editing-associated properties. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 1410–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Reyes, J. and Sollner-Webb, B. 1996. Trypanosome U-deletional RNA editing involves guide RNA-directed endonuclease cleavage, terminal U exonuclease, and RNA ligase activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93: 8901–8906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Reyes, J., Rusché, L.N., and Sollner-Webb, B. 1998. Trypanosoma brucei U insertion and U deletion activities co-purify with an enzymatic editing complex but are differentially optimized. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 3634–3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Reyes, J., Zhelonkina, A., Rusche, L., and Sollner-Webb, B. 2001. Trypanosome RNA editing: Simple guide RNA features enhance U deletion 100-fold. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 884–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Reyes, J., Zhelonkina, A.G., Huang, C.E., and Sollner-Webb, B. 2002. Distinct functions of two RNA ligases in active Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 4652–4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drozdz, M., Palazzo, S.S., Salavati, R., O’Rear, J., Clayton, C., and Stuart, K. 2002. TbMP81 is required for RNA editing in Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J. 21: 1791–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, N.L., Panicucci, B., Igo Jr., R.P., Panigrahi, A.K., Salavati, R., and Stuart, K. 2003. TbMP57 is a 3′ terminal uridylyl transferase (TUTase) of the Trypanosoma brucei editosome. Mol. Cell 11: 1525–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G. and Simpson, L. 2003. Is the trypanosoma brucei REL1 RNA ligase specific for U-deletion RNA editing and the REL2 RNA ligase specific for U-insertion editing? J. Biol. Chem. 278: 27570–27574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman, M.L. and Read, L.K. 1999. Trypanosoma brucei RBP16 is a mitochondrial Y-box family protein with guide RNA binding activity. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 12067–12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, T., Schmid, B., Heumann, H., and Goringer, H.U. 1997. A three-dimensional working model for a guide RNA from Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 2311–2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.K. and Shuman, S. 2002. Bacteriophage T4 RNA ligase 2 (gp24.1) exemplifies a family of RNA ligases found in all phylogenetic domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 12709–12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.E., Cruz-Reyes, J., Zhelonkina, A.G., O’Hearn, S., Wirtz, E., and Sollner-Webb, B. 2001. Roles for ligases in the RNA editing complex of Trypanosoma brucei: Band IV is needed for U-deletion and RNA repair. EMBO J. 20: 4694–4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.E., O’Hearn, S.F., and Sollner-Webb, B. 2002. Assembly and function of the RNA editing complex in Trypanosoma brucei requires band III protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 3194–3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igo, Weston, D.S., Ernst, N.L., Panigrahi, A.K., Salavati, R., and Stuart, K. 2002. Role of uridylylate-specific exoribonuclease activity in Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing. Eukar. Cell 1: 112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable, M.L., Seiwert, S.D., Heidmann, S., and Stuart, K. 1996. RNA editing: A mechanism for gRNA-specified uridylate insertion into precursor mRNA. Science 273: 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller, J., Muller, U.F., Schmid, B., Missel, A., Kruft, V., Stuart, K., and Goringer, H.U. 1997. Trypanosoma brucei gBP21. An arginine-rich mitochondrial protein that binds to guide RNA with high affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 3749–3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison-Antenucci, S. and Hajduk, S.L. 2001. RNA editing-associated protein 1 is an RNA binding protein with specificity for preedited mRNA. Mol. Cell 7: 879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison-Antenucci, S., Sabatini, R.S., Pollard, V.W., and Hajduk, S.L. 1998. Kinetoplastid RNA-editing-associated protein 1 (REAP-1): A novel editing complex protein with repetitive domains. EMBO J. 17: 6368–6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, M.T., Shimamura, M., Grams, J., and Hajduk, S.L. 2001. Identification of candidate mitochondrial RNA editing ligases from Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 7: 167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missel, A. and Goringer, H.U. 1994. Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria contain RNA helicase activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4050–4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missel, A., Nörskau, G., Shu, H.H., and Göringer, H.U. 1995. A putative RNA helicase of the DEAD box family from Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 75: 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missel, A., Souza, A.E., Nörskau, G., and Göringer, H.U. 1997. Disruption of a gene encoding a novel mitochondrial DEAD-box protein in Trypanosoma brucei affects edited mRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 4895–4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, U.F., Lambert, L., and Goringer, H.U. 2001. Annealing of RNA editing substrates facilitated by guide RNA-binding protein gBP21. EMBO J. 20: 1394–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odell, M., Sriskanda, V., Shuman, S., and Nikolov, D.B. 2000. Crystal structure of eukaryotic DNA ligase-adenylate illuminates the mechanism of nick sensing and strand joining. Mol. Cell 6: 1183–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, S.S., Panigrahi, A.K., Igo, R.P., Salavati, R., and Stuart, K. 2003. Kinetoplastid RNA editing ligases: Complex association, characterization, and substrate requirements. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 127: 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, A.K., Gygi, S.P., Ernst, N.L., Igo, R.P., Palazzo, S.S., Schnaufer, A., Weston, D.S., Carmean, N., Salavati, R., Aebersold, R., et al. 2001a. Association of two novel proteins, TbMP52 and TbMP48, with the Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 380–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, A.K., Schnaufer, A., Carmean, N., Igo Jr., R.P., Gygi, S.P., Ernst, N.L., Palazzo, S.S., Weston, D.S., Aebersold, R., Salavati, R., et al. 2001b. Four related proteins of the Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 6833–6840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, A.K., Allen, T.E., Stuart, K., Haynes, P.A., and Gygi, S.P. 2003a. Mass spectrometric analysis of the editosome and other multiprotein complexes in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 14: 728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, A.K., Schnaufer, A., Ernst, N.L., Wang, B., Carmean, N., Salavati, R., and Stuart, K. 2003b. Identification of novel components of Trypanosoma brucei editosomes. RNA 9: 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, M. and Read, L.K. 2003. RBP16 is a multifunctional gene regulatory protein involved in editing and stabilization of specific mitochondrial mRNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 9: 457–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, M., Miller, M.M., and Read, L.K. 2000. RNA-binding properties of the mitochondrial Y-box protein RBP16. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 1266–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris, M., Simpson, A.M., Grunstein, J., Liliental, J.E., Frech, G.C., and Simpson, L. 1997. Native gel analysis of ribonucleoprotein complexes from a Leishmania tarentolae mitochondrial extract. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 85: 9–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber, J., Ryder, U., Lamond, A.I., and Mann, M. 2002. Large-scale proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome. Genome Res. 12: 1231–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusché, L.N., Cruz-Reyes, J., Piller, K.J., and Sollner-Webb, B. 1997. Purification of a functional enzymatic editing complex from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J. 16: 4069–4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusché, L.N., Huang, C.E., Piller, K.J., Hemann, M., Wirtz, E., and Sollner-Webb, B. 2001. The two RNA ligases of the Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complex: Cloning the essential band IV gene and identifying the band V gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 979–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, R. and Hajduk, S.L. 1995. RNA ligase and its involvement in guide RNA/mRNA chimera formation. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 7233–7240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnaufer, A., Panigrahi, A.K., Panicucci, B., Igo, R.P., Salavati, R., and Stuart, K. 2001. An RNA ligase essential for RNA editing and survival of the bloodstream form of Trypanosoma brucei. Science 291: 2159–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert, S.D., Heidmann, S., and Stuart, K. 1996. Direct visualization of uridylate deletion in vitro suggests a mechanism for kinetoplastid RNA editing. Cell 84: 831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman, S. and Schwer, B. 1995. RNA capping enzyme and DNA ligase: A superfamily of covalent nucleotidyl transferases. Mol. Microbiol. 17: 405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, L., Sbicego, S., and Aphasizhev, R. 2003. Uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria: A complex business. RNA 9: 265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, K., Panigrahi, A.K., Schnaufer, A., Drozdz, M., Clayton, C., and Salavati, R. 2002. Composition of the editing complex of Trypanosoma brucei. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 357: 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhamme, L., Perez-Morga, D., Marchal, C., Speijer, D., Lambert, L., Geuskens, M., Alexandre, S., Ismaïli, N., Göringer, U., Benne, R., et al. 1998. Trypanosoma brucei TBRGG1, a mitochondrial oligo(U)-binding protein that co-localizes with an in vitro RNA editing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 21825–21833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]