Abstract

An internal ribosome entry segment (IRES) has been identified in the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) of two members of the myc family of proto-oncogenes, c-myc and N-myc. Hence, the synthesis of c-Myc and N-Myc polypeptides can involve the alternative mechanism of internal initiation. Here, we show that the 5′ UTR of L-myc, another myc family member, also contains an IRES. Previous studies have shown that the translation of mRNAs containing the c-myc and N-myc IRESs can involve both cap-dependent initiation and internal initiation. In contrast, the data presented here suggest that internal initiation can account for all of the translation initiation that occurs on an mRNA with the L-myc IRES in its 5′ UTR. Like many other cellular IRESs, the L-myc IRES appears to be modular in nature and the entire 5′ UTR is required for maximum IRES efficiency. The ribosome entry window within the L-myc IRES is located some distance upstream of the initiation codon, and thus, this IRES uses a “land and scan” mechanism to initiate translation. Finally, we have derived a secondary structural model for the IRES. The model confirms that the L-myc IRES is highly structured and predicts that a pseudoknot may form near the 5′ end of the mRNA.

Keywords: internal ribosome entry, IRES, pseudoknot, L-myc

INTRODUCTION

The L-myc gene belongs to the myc family of proto-oncogenes and shares extensive sequence and functional homology with two other members of this intensely studied group, c-myc and N-myc (Nau et al. 1985; Legouy et al. 1987). Overexpression of all three genes has been associated with neoplasia and causes cell transformation (Boxer and Dang 2001; Lutz et al. 2002; Pelengaris et al. 2002; Strieder and Lutz 2002). Each gene encodes a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper (bHLHzip) protein that interacts with another bHLHzip protein known as Max (Blackwood et al. 1992). Myc-Max heterodimers bind to DNA sequences called E-boxes (CANNTG) and thereby facilitate activation of gene expression (Blackwood et al. 1992). Of the three genes, L-myc is the least efficient at promoting cellular transformation and transcription (Birrer et al. 1988a,b). Furthermore, the c-myc and N-myc genes were shown to be essential for embryonic viability, but in sharp contrast, L-myc homozygous knockout mice are viable, show no obvious developmental defects, and exhibit normal physiology (Hatton et al. 1996). All three genes display distinct expression patterns throughout development and in the adult organism. L-Myc expression is highly restricted with respect to both tissue and developmental stage. During embryogenesis, L-myc is expressed in the nervous system, kidney, and lung, whereas in the adult, expression is maintained in the lung, but in no other tissue (Zimmerman et al. 1986).

Like the c-myc and N-myc genes, the L-myc gene is organized into three exons and two introns. In all three genes, the main initiation codon is located toward the 5′ end of exon 2, and therefore, exon 1 forms the majority of the 5′ UTR. However, in the case of L-myc, the retention of intron A in a proportion of mature transcripts generates an alternative and longer 5′ UTR (Kaye et al. 1988). Both L-myc 5′ UTRs are long and GC-rich, and consequently, would be expected to adopt a complex secondary structure (Kaye et al. 1988). The presence of extensive RNA structure can represent a significant barrier to the scanning ribosome and suggests that the 5′ UTR may be involved in regulating L-myc polypeptide synthesis.

Given that the L-myc gene is homologous to the N-myc and c-myc genes with respect to both gene function and organization, it is feasible that the synthesis of these three polypeptides could be regulated using similar mechanisms. In our laboratory, evidence was obtained demonstrating that c-myc and N-myc protein synthesis can proceed by the mechanism of internal translation initiation (Stoneley et al. 1998; Jopling and Willis 2001). In this process, the ribosome is recruited to an internal site on the mRNA that is often some considerable distance from the cap structure. A complex RNA structural element present in the 5′ UTR, which is known as an internal ribosome entry segment (IRES), mediates internal initiation (Hellen and Sarnow 2001). Neither version of the L-myc 5′ UTR shows significant sequence similarity to those of c-myc or N-myc. Nevertheless, both L-myc 5′ UTRs have features in common with these IRESs, in that they are long and are predicted to attain a high degree of secondary structure. These observations suggested that one or both L-myc 5′ UTRs may contain an internal ribosome entry segment, and we have tested that hypothesis herein.

We show that the shorter version of the L-myc 5′ UTR contains an IRES. Moreover, our data indicates that internal initiation could potentially account for all of the translation initiation that occurs on a monocistronic mRNA with this element in its 5′ UTR. Using deletion and mutational analysis, we show that the entire 5′ UTR of L-myc is required for IRES function, and that the ribosome enters at a site some distance upstream of the initiation codon. In addition, we propose a secondary structural model for the L-myc IRES. Our model confirms that the IRES is highly structured and contains a potential pseudoknot, a feature common to other cellular and viral IRESs (Wang et al. 1995; Rijnbrand et al. 1997; Le Quesne et al. 2001).

RESULTS

The L-myc 5′ UTR regulates the expression of a reporter gene

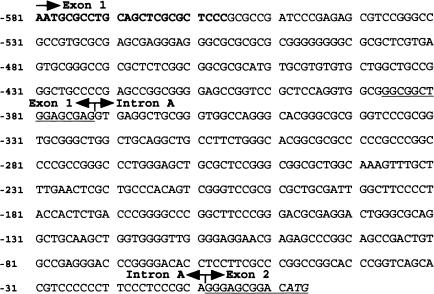

Alternative splicing gives rise to two different isoforms of the L-myc 5′ UTR (Kaye et al. 1988). The most commonly found leader sequence is 217 nucleotides long, but the retention of intron A in a proportion of mRNAs also yields a version that is 581 nt long. Both sequences are highly GC-rich with the shorter and longer isoforms containing 80% and 77.5% G+C, respectively (Fig. 1 ▶). To analyze the function of the short L-myc 5′ UTR, we first amplified the DNA sequence from HL60 cDNA (Fig. 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1.

Sequence of the L-myc 5′ UTR. The sequence of the 5′ region of the L-myc gene from the transcription initiation site to the first initiation codon. Exon 1, intron A, and exon 2 are indicated with arrows, and the start codon is italicized. The short isoform of the L-myc 5′ UTR is composed of exon 1 and 10 nucleotides of exon 2, whereas the long isoform also retains intron A. A DNA fragment encoding the short isoform was amplified from HL60 cDNA using the primers LF2 and LR2 (see Materials and Methods). Shown in bold is the sequence used to design the primer LF2 (5′-AATGCGCCTG CAGCTCGCGCTCCC-3′). To ensure that only the short 5′ UTR was amplified, the oligonucleotide LR2 was designed to complement the sequence from the 3′ end of exon 1 and the 5′ end of exon 2 (5′-GGCGGCTGGAGCGAGGGGAGCCGACATG-3′). This sequence is underlined.

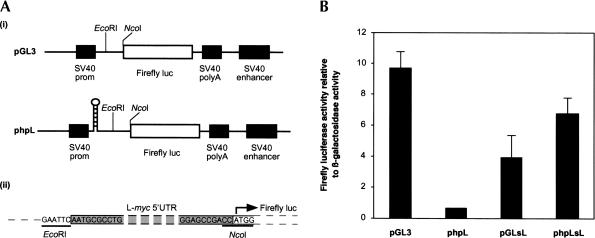

Structure-prediction algorithms imply that the short L-myc 5′ UTR contains extensive RNA secondary structure, and could therefore potentially regulate gene expression. To examine the effect of the L-myc 5′ UTR on downstream gene expression, we introduced this sequence into the reporter construct pGL3 immediately upstream of the luciferase-coding region (Fig. 2A ▶ [i]). The resulting construct (pGLsL) produces mRNAs with the L-myc 5′ UTR fused directly to the luciferase-coding region (Fig. 2A ▶ [ii]). In addition, we wanted to determine whether translation initiation on an mRNA with the L-myc 5′ UTR in its 5′ leader sequence occurs by the classic cap-dependent mechanism. To achieve this, we inserted the L-myc 5′ UTR sequence into phpL between the inverted repeat sequence and firefly luciferase (Fig. 2A ▶). The inverted repeat sequence forms a very stable RNA hairpin structure (−87 Kcal/mole) at the 5′ end of the mRNAs produced by this construct (phpLsL). In prior studies, we have shown that this RNA structure severely inhibits cap-dependent translation initiation (Coldwell et al. 2001). Thus, by comparing the expression of firefly luciferase from pGLsL and phpLsL, we can assess the contribution of cap-dependent initiation to the translation of an mRNA containing the L-myc 5′ UTR.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of the L-myc 5′ UTR on reporter gene expression. (A) (i) Schematic representation of the firefly luciferase expression cassette of pGL3 and phpL. As detailed in Stoneley et al. (2000), phpL was created from pGL3 by introducing an inverted repeat sequence into the SpeI site. (ii) Inserting the L-myc 5′ UTR sequence between the EcoRI and NcoI sites of pGL3 and phpL created the constructs pGLsL and phpLsL, respectively. In these constructs, the 3′ end of the 5′ UTR sequence is followed immediately by the firefly luciferase initiation codon. Hence, the relative positions of the initiation codon and the 5′ UTR are the same in these constructs as in the L-myc mRNA. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with the constructs pGL3, phpL, pGLsL, and phpLsL in conjunction with the plasmid pcDNA3.1/HisB/lacZ. Lysates were prepared from the cells 48 h post-transfection, and the activity of firefly luciferase was determined as described in Materials and Methods. To account for variations in transfection efficiency firefly luciferase activity was normalized to that of β-galactosidase.

HeLa cells were transfected with pGL3, pGLsL, phpL, and phpLsL, and the luciferase activity from each construct was determined (Fig. 2B ▶). The presence of the L-myc 5′ UTR directly upstream of the luciferase-coding region reduced the amount of reporter enzyme produced by ~66%, and therefore indicates that this sequence can modulate gene expression (Fig. 2B ▶). As expected, the RNA hairpin sequence in the construct phpL reduced luciferase expression by 95% when compared with the control construct pGL3 (Fig. 2B ▶). However, when the L-myc 5′ UTR was introduced between the hairpin and the reporter gene, luciferase expression was stimulated ~10-fold to a level above that observed with pGLsL (Fig. 2B ▶). Because we know that the hairpin structure efficiently inhibits cap-dependent translation initiation, an alternative mechanism must be responsible for the increased synthesis of luciferase (Fig. 2B ▶). Taken together, these data indicate that the L-myc 5′ UTR regulates polypeptide synthesis from a downstream gene, but not via the classic cap-dependent mechanism. It is noticeable that there is a small, but reproducible increase in luciferase expression when the RNA hairpin is positioned upstream of the L-myc 5′ UTR. A similar effect was observed in a previous study when a hairpin structure was located upstream of the poliovirus IRES (Hambidge and Sarnow 1991). It was suggested that scanning ribosomes interfered with the action of the poliovirus IRES. Thus, by comparison, translation mediated by the L-myc 5′ UTR may also be affected by the scanning process to some degree (Fig. 2B ▶; cf. pGLsL with phpLsL).

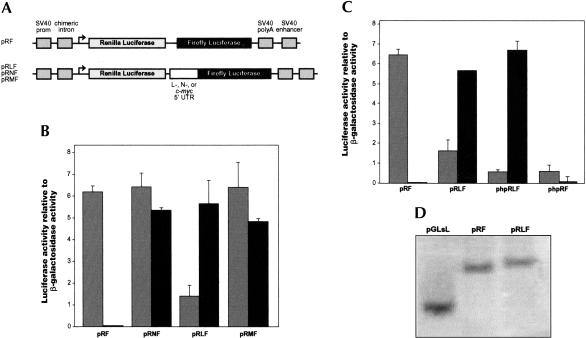

The 5′ UTR of L-myc contains an internal ribosome entry segment

One potential explanation for the foregoing data would be the existence of an IRES in the L-myc 5′ UTR. We and others have shown that translation initiation on the c-myc and N-myc mRNAs can occur by the mechanism of internal ribosome entry (Nanbru et al. 1997; Stoneley et al. 1998; Jopling and Willis 2001). Accordingly, constructs were generated to determine whether the L-myc 5′ UTR also contains an IRES. The L-myc 5′ UTR fragment was inserted into the intercistronic region of the control dicistronic reporter vector pRF, thereby creating pRLF (Fig. 3A ▶). HeLa cells were transfected with pRF, pRLF, and dicistronic constructs containing the c-myc and N-myc IRESs, pRMF and pRNF, respectively (Fig. 3A ▶). Comparison of the normalized firefly luciferase activities from pRF and pRLF indicates that when introduced into a dicistronic mRNA, the L-myc 5′ UTR stimulated expression from the downstream cistron by 78-fold (Fig. 3B ▶). Moreover, the effect of the L-myc 5′ UTR on the downstream cistron is comparable with that of the cellular IRESs, c-myc and N-myc (Fig. 3B ▶).

FIGURE 3.

The L-myc 5′ UTR contains an IRES. (A) Schematic representation of the expression cassette of the dual-luciferase dicistronic constructs pRF, pRMF, pRNF, and pRLF. The construct pRLF was generated inserting the L-myc 5′ UTR sequence into pRF between the EcoRI and NcoI sites. The remaining constructs have been described elsewhere (Stoneley et al. 1998; Jopling and Willis 2001). As described in Figure 2A ▶ (ii), the 5′ UTR sequence is inserted into these constructs such that the relative positions of the initiation codon and the 5′ UTR are the same as in the L-myc mRNA. The sequence of the junction between the L-myc 5′ UTR and the firefly luciferase-coding region is identical to that shown in Figure 2A ▶ (ii). (B) The constructs detailed above were transfected into HeLa cells in combination with pcDNA3.1/HisB/lacZ. Renilla luciferase, firefly luciferase, and β-galactosidase activities were determined 48 h post-transfection. Renilla luciferase (gray) and firefly luciferase (black) activities were normalized to β-galactosidase activity. (C) The L-myc 5′ UTR sequence was inserted into the construct phpRF between the EcoRI and NcoI sites. HeLa cells were transfected with pRF, phpRF, pRLF, and phpRLF in conjunction with pcDN3.1/HisB/lacZ. Normalized Renilla luciferase (gray) and firefly luciferase (black) activities were then determined as described previously. (D) Total RNA was isolated from HeLa cells that had been transfected with pGLsL, pRF, and pRLF. Poly(A)+ RNA was purified from these RNA samples, and Northern analysis was performed essentially as described in West et al. (1995). Transcripts containing firefly luciferase-coding sequence were detected using a radiolabeled probe (Coldwell et al. 2000).

Clearly, the observation that the L-myc 5′ UTR can substantially increase reporter gene expression from the downstream cistron of a dicistronic mRNA is consistent with the presence of an IRES in this sequence. Nevertheless, two alternative mechanisms could produce a similar result, namely, enhanced ribosomal reinitiation at the firefly luciferase initiation codon and the production of functional firefly luciferase mRNAs due to splicing, RNA cleavage, or a cryptic promoter.

It is possible to distinguish between ribosomal reinitiation and internal initiation, as the former is a cap-dependent mechanism, whereas in the latter process, ribosomes are recruited to the IRES independent of the cap structure. Genuine internal initiation at the downstream cistron of a dicistronic mRNA is not affected by a reduction in cap-dependent translation initiation at the upstream cistron. In contrast, a decrease in translation initiation at the upstream cistron would produce a concomitant reduction in the rate of ribosomal reinitiation at the downstream cistron. Therefore, we inserted the 5′ UTR sequence into phpRF to determine whether translation initiation driven by the L-myc 5′ UTR is sensitive to reduced translation initiation at the 5′ end of a dicistronic mRNA. This construct contains an inverted repeat sequence upstream of the Renilla luciferase-coding region, which produces a stable RNA hairpin structure in the mRNA (−55 Kcal/mole). In prior studies, we have shown that this RNA structure inhibits the cap-dependent synthesis of Renilla luciferase, but it does not affect internal initiation (Stoneley et al. 1998). As expected, the RNA hairpin structure reduced Renilla luciferase expression from the control dicistronic mRNA by 80% (Fig. 3C ▶; pRF and phpRF). In addition, the RNA hairpin decreased cap-dependent translation initiation at the Renilla luciferase start codon when the dicistronic mRNA also contained the L-myc 5′ UTR (Fig. 3C ▶). However, under these circumstances, the apparent effect of the RNA hairpin on Renilla luciferase expression was somewhat reduced (Fig. 3C ▶; pRLF and phpRLF). It should be noted that the L-myc 5′ UTR alone substantially reduces Renilla luciferase expresson, and any further inhibition of cap-dependent translation must occur against this background. In contrast, the expression of firefly luciferase promoted by the L-myc 5′ UTR was unaffected by the RNA hairpin structure (Fig. 3C ▶). Evidently, translation initiation driven by the L-myc 5′ UTR is not dependent on ribosomes scanning from the 5′ end of the dicistronic mRNA and therefore, cannot be due to enhanced ribosomal reinitiation. Moreover, these data are consistent with the presence of an IRES in the L-myc 5′ UTR.

Finally, to address the possible production of functional monocistronic firefly luciferase mRNAs through the mechanisms mentioned previously, we determined the sizes of the mRNAs expressed from pGLsL, pRF, and pRLF. Northern analysis was performed and mRNAs containing firefly luciferase-coding sequence were detected using a radiolabeled probe (Fig. 3D ▶). All three constructs expressed mRNAs of the expected size, and in particular, there was no evidence of monocistronic firefly luciferase mRNAs produced from the dicistronic construct pRLF (Fig. 3D ▶).

Collectively, the above data strongly suggest that there is an IRES within the short 5′ UTR of the L-myc mRNA. Therefore, L-myc mRNAs bearing this sequence can be translated by internal initiation. Unfortunately, in a similar study of the longer L-myc 5′ UTR, we were unable to provide conclusive evidence for the presence of an IRES. Northern analysis clearly showed that a dicistronic construct containing the long L-myc 5′ UTR sequence produced fragmented mRNAs, probably as a result of splicing events (data not shown).

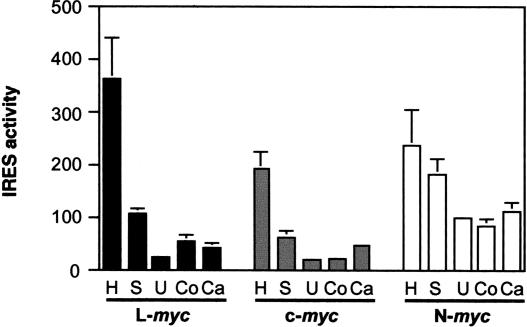

Comparison of L-myc IRES-mediated internal initiation in a range of cell types

To investigate how widely the L-myc IRES is utilized, and to compare the activity of this IRES with those found in N- and c-myc, a range of cell types was transfected with pRF, pRMF, pRNF, or pRLF (Fig. 4 ▶). The IRES efficiency in a particular cell line was calculated by comparing the firefly luciferase activity promoted by the IRES with that observed in the absence of the IRES. Clearly, in each cell line, the efficiency of the three myc IRESs differs to some extent. What is more, the activity of each IRES varies somewhat between the cell lines. However, it is noticeable that there is considerably less variation in N-myc IRES activity in these cell lines (Fig. 4 ▶). In these cell lines, the efficiencies of the c- and L-myc IRESs vary by 10- and 15-fold, respectively, whereas the activity of the N-myc IRES varies by only 2.8-fold. We can see this difference most clearly in the U2OS cell line, in which the c-myc and L-myc IRESs stimulate luciferase synthesis by ~20-fold compared with nearly 100-fold for the N-myc IRES. Overall, these data indicate that, like the c-myc and N-myc IRESs, the L-myc IRES can promote translation initiation in cell lines derived from different tissues, and the activity of the IRES varies in a cell-type-specific manner (Stoneley et al. 2000; Jopling and Willis 2001).

FIGURE 4.

A comparison of the c-, N-, and L-myc IRES efficiency in a range of cell lines. The constructs pRF, pRLF, pRMF, and pRNF were transfected into HeLa (H; cervical carcinoma), SaOS2 (S; osteosarcoma), U2OS (U; osteosarcoma), Cos-1 (Co; SV40-transformed epithelial cells), and Cal51 (Ca; breast carcinoma) cells in conjunction with pcDNA3.1/HisB/lacZ. Cell lysates were prepared 48 h after transfection, and the activities of firefly luciferase, Renilla luciferase (data not shown), and β-galactosidase were determined. After normalizing firefly luciferase activity to that of β-galactosidase, the IRES activity was calculated using the ratio (firefly luciferase activity from pRLF, pRMF, or pRNF)/(firefly luciferase activity from pRF).

Mapping the L-myc IRES

To define the boundaries of the L-myc IRES, a series of dicistronic constructs was generated containing sections of the sequence coding for the 5′ UTR (Fig. 5A ▶). We then determined how effective these truncated sequences are at promoting internal initiation compared with the full-length 5′ UTR. The fragments ABC and BCD retained ~50% and 58% of the activity of the full-length 5′ UTR, respectively (Fig. 5B ▶). Therefore, it is clear that the boundaries of the IRES are located within the A and D fragments, and that removal of even small segments from either end of the L-myc 5′ UTR can substantially reduce the efficacy of the IRES. In this regard, it is similar to the N-myc IRES (Jopling and Willis 2001). The deletion of larger sections of 5′ UTR sequence resulted in a corresponding decrease in IRES activity (Fig. 5B ▶). Thus, sequences throughout the 5′ UTR are involved in internal initiation.

FIGURE 5.

Deletion analysis of the L-myc IRES. (A) Diagrammatic representation of the truncated versions of the L-myc 5′ UTR used in the deletion analysis. DNA fragments were amplified using PCR (using oligonucleotides as described in Materials and Methods) and inserted into the dicistronic construct pRF at the EcoRI and NcoI sites. (B) The constructs pRF, pRLF, and the dicistronic constructs containing the truncated 5′ UTR sequences, as described above, were transfected into HeLa cells, and lysates were prepared 48 h post-transfection. All constructs were cotransfected with pcDNA3.1/HisB/lacZ. Renilla luciferase (gray) and firefly luciferase (black) activities were determined and normalized to β-galactosidase activities.

Experiments were then performed to locate the point of ribosome entry within the L-myc IRES. For the two cellular IRESs analyzed thus far, the data suggests that the 40S subunit is recruited to the IRES some distance upstream of the initiation codon, after which it migrates in a 5′–3′ direction until start-codon recognition occurs (Le Quesne et al. 2001; Mitchell et al. 2003). This “land and scan” mechanism is also found in the IRESs of the entero- and rhinoviruses (Belsham and Jackson 2000).

To locate the ribosome entry window within the L-myc IRES, we introduced AUG initiation codons at various positions throughout the sequence using site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 6A ▶). In addition, where necessary, we improved the surrounding sequence context to ensure that these initiation codons were recognized efficiently by the ribosome. We positioned the AUG codons such that when the mutant IRES was inserted into the dicistronic construct pRF, an upstream open reading frame (uORF) was created in the IRES. This uORF is not only out of frame with the firefly luciferase-coding region, but also overlaps with this sequence. Hence, if the ribosome entry window lies upstream of the inserted AUG, polypeptide synthesis will initiate at the uORF, resulting in a concomitant decrease in firefly luciferase expression. However, if the point of ribosome entry lies between the upstream AUG and the reporter gene initiation codon, there will be no change in firefly luciferase synthesis.

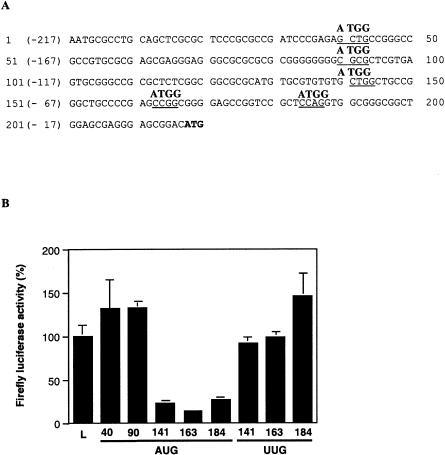

FIGURE 6.

Locating the ribosome entry window in the L-myc IRES. (A) The sequence of the short L-myc 5′ UTR indicating the positions at which initiation codons were introduced. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to alter the underlined sequence to ATGG using oligonucleotides (see Materials and Methods). In addition, the sequences at 141 to 144, 163 to 166, and 184 to 187 were also altered to UUGG. Mutated L-myc 5′ UTR PCR fragments were then inserted into the dicistronic construct pRF. The position of each mutated sequence is numbered from the A of the ATGG or U of UUGG. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with pRLF (L) and the dicistronic constructs containing the mutated L-myc sequences (AUG 40, AUG 90, AUG 141, AUG 163, AUG 184, UUG 141, UUG 163, and UUG 184) in conjunction with pcDNA3.1/HisB/lacZ. Lysates were prepared 48 h post-transfection. The data are represented as the percentage firefly luciferase activity compared with the activity from pRLF.

The dicistronic mRNAs containing the mutant IRESs and the control mRNA containing the unaltered IRES were expressed in HeLa cells (Fig. 6B ▶). Of the five AUG codons we introduced into the 5′ UTR, only the two AUGs located at positions 40 and 90 had no effect on firefly luciferase expression (Fig. 6A,B ▶). The other three AUG mutations reduced the synthesis of firefly luciferase to some degree. We also altered the sequence at the 141, 163, and 184 positions to UUGG to ensure that mutations at these positions do not effect luciferase expression simply by perturbing the RNA structure. As none of the UUGG mutations reduced the synthesis of firefly luciferase, we can conclude that the inhibition observed with the AUG mutations is the result of the presence of upstream initiation codons in the IRES and not a change in RNA structure (Fig. 6B ▶). Overall, the data suggests that the ribosome is capable of being recruited to the IRES at a point between positions 90 and 141. Moreover, it implies that the L-myc IRES employs a “land and scan”-type mechanism

Derivation of a secondary structural model for the L-myc IRES

To begin dissecting the mechanism of action of the L-myc IRES, it is first necessary to derive a secondary structure model for the IRES. In our laboratory, we have produced models for the c-myc and apaf-1 IRESs, and in the case of the apaf-1 IRES, the model has gone some way toward advancing our understanding of the mechanisms involved (Le Quesne et al. 2001; Mitchell et al. 2003).

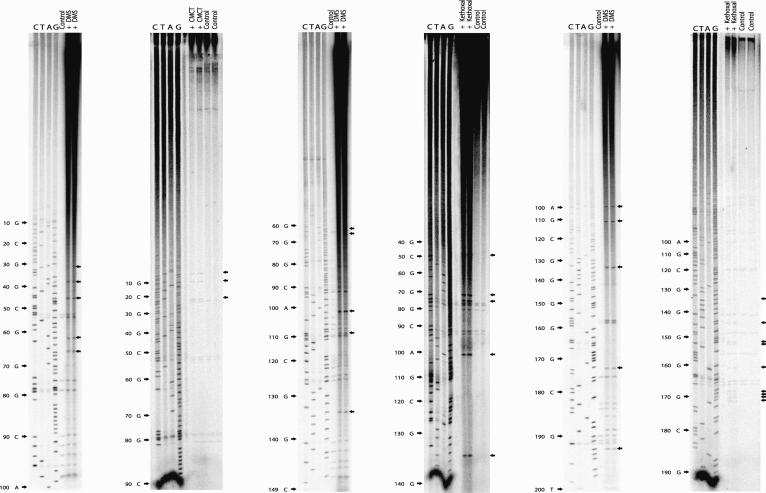

L-myc IRES RNA was generated using in vitro transcription reactions, resuspended in probing buffer, and then heated rapidly and cooled gradually to refold the molecule into its native conformation (Le Quesne et al. 2001). The RNA was then incubated with one of three agents to distinguish unpaired and Watson-Crick-paired bases. DMS, kethoxal, and CMCT (Fig. 7 ▶) were used to ascertain unpaired bases, and paired bases were identified using Ribonuclease V1 (data not shown). Primer extension was then performed on the modified RNA and on mock-treated RNA using oligonucleotides in the presence of radioactively labeled dCTP. The products of these primer extension reactions were then subjected to PAGE in conjunction with the corresponding DNA-sequencing ladder to allow identification of modified residues (Fig. 7 ▶).

FIGURE 7.

Chemical and enzymatic probing of the L-myc IRES. Renatured in vitro-transcribed L-myc IRES RNA was treated with DMS, kethoxal, CMCT, or RNase V1 (data not shown) as described in Materials and Methods. Primer extension was then performed with these samples and a mock-treated L-myc IRES RNA sample (control) using [α-32P]dCTP and an oligonucleotide (see Materials and Methods). The products of these reactions, together with the corresponding DNA-sequencing reaction were subjected to electrophoresis on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide/urea gel. The black arrows indicate sites of chemical modification.

It can be seen that there are very few residues that were susceptible to DMS or other chemical modification, suggesting that the L-myc IRES RNA is highly structured (Fig. 7 ▶). These sites are scattered throughout the IRES, and are therefore likely to correspond to the end of loops, implying that they are the product of unpaired residues (Fig. 7 ▶). These data suggest that the L-myc IRES contains extensive regions of RNA helix and relatively little single-stranded RNA; this was further confirmed using RNAse VI (data not shown).

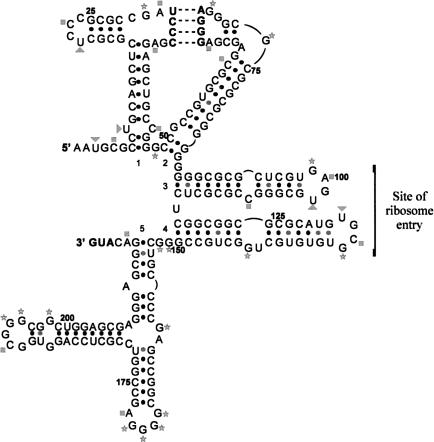

Secondary structure model for the L-myc IRES

Having obtained a set of data recording the accessibility of bases in the L-myc IRES to modifying chemicals and RNAse VI, we were then able to use this to apply constraints to the structure-prediction algorithm Mfold (Zuker et al. 1999) incorporating version 3.0 of the Turner rules (Mathews et al. 1999). Using this approach, we generated a secondary structural model for the L-myc IRES (Fig. 8 ▶). Our model suggests that the IRES is highly structured and consists of five motifs. Overall, the model for the L-myc IRES bears little similarity to the structures of either the c-myc or apaf-1 IRES (Le Quesne et al. 2001; Mitchell et al. 2003). However, motif 5 contains a G(n)NRA pentaloop, a common structural element often involved in RNA–RNA interactions, which is also found in the c-myc IRES (Le Quesne et al. 2001). It is noticeable that the apical loop and the stem bulge of motif 1 both contain the sequence UCCC. These sequences have the potential to base pair with the GGGA sequences in the apical loop of motif 2 and the G(n)NRA pentaloop of motif 5, thereby forming two pseudoknot structures. Our data indicate that all loops, with the exception of the GGGA sequence of the apical loop of motif 2 and UCCC sequence (shown in bold) in loop 1, are available for chemical modification. Thus, it seems possible that only a pseudoknot involving motifs 1 and 2 is capable of forming (Fig. 8 ▶). These structural elements are of considerable interest, as they have been shown to either inhibit or stimulate the activity of other IRESs, including that of c-myc (Wang et al. 1995; Rijnbrand et al. 1997; Le Quesne et al. 2001; Yaman et al. 2003).

FIGURE 8.

Secondary structural model of the L-myc IRES. The secondary structural model of the L-myc IRES was derived using the chemical and enzymatic accessibility data to constrain the Mfold algorithm. Five regions of helical structure are indicated (1–5). Nucleotides involved in pairing interactions are indicated by a black dot. The sequences involved in forming the potential pseudoknot are indicated in bold, and the region of ribosome entry is also indicated. The position of modifications are indicated as follow; (squares) sites of DMS modification (A,C); (triangles) sites of CMCT modification (U); (stars) sites of kethoxal modification (G). Numbering is from 5′ to 3′.

The model also allows us to locate the position of ribosome entry within the IRES. It lies approximately within motifs 3 and 4, in a region containing few unpaired bases. Therefore, it seems likely that a structural change, resulting in a more open conformation, would be necessary for ribosome binding to occur in this region. Such a mechanism operates in the apaf-1 IRES and is dependent on the RNA-binding proteins unr and PTB (Mitchell et al. 2003).

DISCUSSION

Extensive study of the picornaviral IRESs has allowed their subdivision into different categories on the basis of structural and functional similarities (Belsham and Jackson 2000). In contrast, although IRESs have been identified in many cellular genes, as yet, no unifying characteristics have emerged (Hellen and Sarnow 2001; Bonnal et al. 2003). Here, we have demonstrated that the 5′ UTR of the proto-oncogene L-myc contains an IRES (Fig. 3 ▶). The activity of the L-myc IRES compares favorably with that of the c-myc and N-myc IRESs in a dicistronic assay (Fig. 3B ▶). Identification of IRESs in three members of the myc gene family will enable us to compare the features of internal ribosome entry in these closely related genes (Stoneley et al. 1998; Jopling and Willis 2001).

It is noticeable that the L-myc IRES substantially reduces the expression from the upstream cistron of the dicistronic mRNA (Fig. 3B ▶). A similar phenomenon has been observed with some picornaviral IRESs and the Apaf-1 IRES (Borman and Jackson 1992; Coldwell et al. 2000). It has been suggested that this could reflect a competition between cap-dependent and IRES-dependent translation on the same dicistronic mRNA. However, in this instance, there may be an alternative explanation. We have observed an increase in PKR activity when exogenous mRNAs containing the L-myc 5′ UTR are transiently expressed in cells (data not shown). Clearly, an increase in the concentration of active PKR could effect this reduction in cap-dependent translation through phosphorylation of eIF2α. Further studies are underway to assess whether PKR is implicated in the expression of endogenous L-myc protein.

One intriguing difference between the L-myc IRES and IRESs of the c-myc and N-myc genes has already emerged from this study. The translational efficiency of a monocistronic mRNA with either the c-myc or the N-myc IRES in its 5′ UTR is substantially reduced when cap-dependent initiation is blocked with a very stable RNA hairpin structure (Stoneley et al. 2000; Jopling and Willis 2001). These observations indicate that mRNAs containing either of these IRESs can be translated via a cap-dependent mechanism in addition to internal initiation. In contrast, when the same conditions are applied to an mRNA with the L-myc IRES in its 5′ UTR, the translational efficiency of the mRNA is marginally increased. Hence, translation initiation on this mRNA does not appear to involve a cap-dependent component, and internal initiation promoted by the L-myc IRES could therefore account for all of the translation initiation that occurs on such an mRNA. Consequently, unlike the c-myc and N-myc 5′ UTRs, it is possible that translation initiation driven by the short L-myc 5′ UTR only involves internal initiation.

As with many other cellular IRESs, including the c-myc and N-myc IRESs, the activity of the L-myc IRES varies considerably in cell lines of different origin (Fig. 4 ▶; Coldwell et al. 2000; Creancier et al. 2000; Stoneley et al. 2000; Jopling and Willis 2001; Pickering et al. 2003). Although the precise explanation for this phenomenon has yet to be determined, there is evidence that in some instances it may be due, in part, to IRES trans-acting factors (ITAFs; Evans et al. 2003; Mitchell et al. 2003; Pickering et al. 2003). Recently, it has been shown that members of the hnRNPK family interact with and stimulate the c-myc IRES in vitro and in vivo (Evans et al. 2003), therefore, it would be of considerable interest to determine the effects of these proteins on L-myc IRES function.

Deletion analysis of the L-myc IRES demonstrates that removing sequences at the 5′ or 3′ end substantially reduces internal initiation (Fig. 5 ▶). In this respect, the L-myc IRES behaves in a similar manner to the N-myc IRES. By comparison, the removal of sequences from either end of the c-myc IRES results in a more gradual decrease in IRES activity (Stoneley et al. 1998; Jopling and Willis 2001). However, it is clear from the deletion analysis that sequences throughout the L-myc IRES are involved in internal initiation (Fig. 5 ▶). Thus, it would appear that like the c-myc and N-myc IRESs, the L-myc IRES is modular in nature, and that these modules cooperate to direct efficient internal initiation. A number of other cellular IRESs have also been shown to be modular. For example, the Bip and PDGF IRESs can be divided into nonoverlapping fragments that demonstrate partial IRES activity (Yang and Sarnow 1997; Sella et al. 1999). The theory that cellular IRESs can be modular is supported by the observation that a short segment of the Gtx IRES shows enhanced activity when present in multiple copies (Chappell et al. 2000). The complementarity to rRNA observed in the Gtx IRES module appears to be a specialized mechanism that is not used by the myc genes, and it is likely that the modular nature of myc IRESs is determined by the cooperation of structural domains.

We have also mapped the region of the L-myc IRES to which the ribosome is recruited by introducing out-of-frame AUG codons throughout the IRES (Fig. 6 ▶). This analysis has revealed further similarities between the c-myc and L-myc IRESs. In both cases, the ribosome is recruited to a site some distance upstream of the initiation codon and then traverses the remainder of the IRES by a scanning mechanism (Le Quesne et al. 2001; Fig. 6 ▶). Thus, both IRESs use a “land and scan” mechanism characteristic of the type I picornaviral IRESs (Belsham and Jackson 2000). However, the ribosome entry windows of c- and L-myc do not contain a polypyrimidine tract, which is a feature of the ribosome-landing site of the picornaviral IRESs. The recruitment of ribosomes to cellular IRESs appears to occur by a somewhat different mechanism to that used by the type I picornaviral IRESs, despite the similarities in function shown by ribosome binding and scanning (Le Quesne et al. 2001; Pederson et al. 2002; Mitchell et al. 2003; Fig. 6 ▶).

Finally, we have derived a secondary structural model for the L-myc IRES by constraining the Mfold algorithm with data obtained from chemical and enzymatic probing of the IRES (Figs. 7 ▶, 8 ▶). The model is quite distinct from any of the other structures proposed for cellular IRESs (Le Quesne et al. 2001; Pedersen et al. 2002; Mitchell et al. 2003; Yaman et al. 2003). Our model predicts that the L-myc IRES contains a high degree of secondary structure and can be subdivided into five motifs. It is noticeable that the ribosome entry window is located in a region that consists of mostly paired bases (Fig. 8 ▶). Thus, it seems likely that a conformational change must occur in this region before the ribosome can be recruited. A similar structural alteration is required before the ribosome can interact with the apaf-1 IRES (Mitchell et al. 2003). In this case, the interaction of the RNA-binding proteins unr and PTB with the IRES results in a more open conformation in the region encompassing the ribosome entry window. It is thought that ribosome binding to the IRES is facilitated by this change in RNA structure (Mitchell et al. 2003). We predict that a pseudoknot that is formed through the interaction of the apical loop of motif 2 with the stem bulge of motif 1, upstream of the ribosome landing region. Pseudoknots are known to influence the activity of both viral and cellular IRESs. The pseudoknots found in the hepatitis C virus and classical swine fever virus IRESs have been shown to be important for IRES function (Wang et al. 1995; Rijnbrand et al. 1997), whereas those located in the c-myc and Cat-1 IRESs appear to inhibit the activity of these IRESs (Le Quesne et al. 2001; Yaman et al. 2003). We are currently using this structural model to probe the mechanism of L-myc internal initiation, and the significance, if any, of the pseudoknot.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs

The plasmids, pGL3, phpL are described in Stoneley et al. (2000). PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) was used to amplify a DNA fragment encoding the short L-myc 5′ UTR from HL60 cDNA using the oligonucleotides LF2 (5′-TGGAATTCAATGCG GCTGCAGCTGGCGCTCCC-3′) and LR2 (5′-GTGCCATGGCC GCTCCTCGCTCCAGCCGCC-3′). The identity of this fragment was verified by DNA sequencing. The fragment was digested with NcoI and EcoR1 and inserted into pGL3 and phpL between the EcoRI and NcoI sites, thus creating pGLsL and phpLsL, respectively. pRF and pRMF are described in Stoneley et al. (2000), and pRNF is described in Jopling and Willis (2001). To create pRLF, the L-myc 5′ UTR DNA fragment was ligated into pRF between the EcoRI and NcoI sites. Deletion fragments were generated by PCR using the following oligonucleotides: LF2, LR2, LFA (5′-GGCCGAATTCCGCGAGCGAGGGAG-3′), LrA (5′-CTCGCCAT GGCACGGCGGCCCGGA-3′), LFB (5′-CCGCGAATTCGGCG GCGCGCATGT-3′), LRB (5′-GCGCCCATGGGAGAGCGCG GCCCG-3′), LFC (5′-GCGGGAATTCGGTCCGCTCCAGGT-3′), and LRC (5′-GGAGCCATGGGGCTCCCCGCCGGC-3′). DNA fragments ABC, BCD, AB, BC, CD, A, B, C, and D were amplified using the primer sets LF2 and LRC, LFA and LR2, LF2 and LRB, LFA and LRC, LFB and LR2, LF2 and LRA, LRA and LRB, LFB and LRC, and LFC and LR2, respectively. All fragments were first digested with EcoRI and NcoI and then ligated into pRF between the same sites.

PCR mutagenesis

Introduction of each upstream AUG or UUG into the L-myc 5′ UTR sequence was performed using PCR mutagenesis. First, two separate and overlapping fragments of the L-myc 5′ UTR sequence were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs LF2/reverse mutant primer and forward mutant primer/LR2. The products of these reactions were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and then used as a template in a second amplification. In this reaction, the primer set LF2/LR2 is used to amplify the entire 5′ UTR sequence, which now incorporates the mutation. AUG mutations were introduced at nt 40, 90, 141, 163, and 184 using the primer sets laug40F (5′-CGATCCCGAGAATGGCCGGGCCGC-3′) and laug40R (5′-GCGGCCCGGCCATTCTCGGGATC-3′), laug90F (5′-CGGGGGGGGATGGCTCGTGAGTGC-3′) and laug90R (5′-GCACTCACGAGCCATCCCCCCCCG-3′), laug141F (5′-TGCGT GTGTGATGGCTGCCGGGCT-3′) and laug141R (5′-AGCCCGG CAGCCATCACACACGCA-3′), laug163F (5′-GCTGCCCCGAG ATGGCGGGGAGCC-3′) and laug163R (5′-GGCTCCCCGCCA TCTCGGGGCAGC-3′), and laug184F (5′-GCCGGTCCGCTA TGGGTGGCGGGC-3′) and laug184R (5′-GCCCGCCACCCA TAGCGGACCGGC-3′), respectively. UUG mutations were introduced at nt 141, 163, and 184 using the primer pairs luug141F (5′-TGCGTGTGTGTTGGCTGCCGGGCT-3′) and luug141R (5′-AGCCCGGCAGCCAACACACACGCA-3′), luug163F (5′-GCT GCCCCGAGTTGGCGGGGAGCC-3′), and luug163R (5′-GGCTC CCCGCCAACTCGGGGCAGC-3′), and luug184F (5′-GCCGGTC CGCTTTGGGTGGCGGGC-3′) and luug184R (5′-GCCCGCCACC CAAAGCGGACCGGC-3′), respectively. All mutant L-myc 5′ UTR fragments were digested with EcoRI and NcoI and then ligated into pRF between the same sites.

Cell culture and transient transfections

Cells were typically grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal calf serum under humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cell lines CALU1 and CAL51 were a gift kindly provided by Dr. G. Packham (CRUK unit, Southampton, UK). All other lines were purchased originally from ATCC. Cells were transfected using FuGene 6 (Roche) as specified by the manufacturer. Alternatively, calcium phosphate-mediated transfections were performed as described (Jordan et al. 1996) with minor modifications (Stoneley et al. 2000). Lysates were prepared from transfected cells using 1× passive lysis buffer. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the “Stop and glo” dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the exception that only 25 μL of each reagent was used. Light emission was measured over 10 sec using an OPTOCOMP I luminometer. Activity of the β-galactosidase transfection control was measured using a Galactolight Plus assay system (Tropix). All transfections were carried out in triplicate on at least three independent occasions.

Northern blot analysis

Poly(A)+ mRNA was prepared using magnetic oligo [dT] beads (Dynal) and analyzed by Northern blotting exactly as described previously (West et al. 1995). DNA probes used for the detection of firefly luciferase mRNA species were also as described (Coldwell et al. 2000).

Chemical structure probing

L-myc 5′ UTR RNA was synthesized using in vitro transcription. The chemical structure-probing protocol was adapted from Stern et al. (1998) and modified as in Le Quesne et al. (2001). RNA (5 μg) was combined with standard structure-probing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0], 0.1M KCl). The mixture was heated to 80°C for 3 min and cooled to 4°C over 1 h in a PCR machine, and then chilled at 0°C for 10 min to permit structural equilibrium. All chemical treatments were carried out at 0°C for 1 h. Different quantities of the various agents were used, typically 1–10 μL.

For treatment of RNA with RNase V1, the protocol was adapted from that given by the manufacturer (Ambion) for RNA structure analysis. Two micrograms of unlabeled RNA was combined with 1 μL of 10× structure buffer, 1 μL enzyme, 1 μg of tRNA, and water to 10 μL. After 10 min at room temperature, the enzyme was removed by phenol/chloroform extraction, and the cleaved RNA was precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 5 μL of water.

Primer extension

The protocol for primer extension was also adapted from Stern et al. (1998). The oligonucleotides used in this analysis were LSMR0 (5′-CATGTCCGCTCCCTCGC-3′), LSMR1 (5′-CCCGCCGGCT CGGGGCAGCC-3′), LSMR2 (5′-GCCGAGAGCGCGGCCCGC AC-3′), and LSMR3 (5′-CTCCCTCGCTCGCGCACGGC-3′). Primer (final concentration 2 pmole/μL) was combined with 1 μL hybridization buffer (250 mM K-HEPES [pH 7.0], 500 mM KCl) and a molar excess of L-myc 5′ UTR RNA. The mixture was incubated at 85°C for 1 min and allowed to cool at room temperature for 10–15 min. Three microlitres of extension mix was added to the cooled hybrid, consisting of 0.5 μL C. therm (Roche) reverse transcriptase and 1 μL of RT–PCR buffer (Roche), 0.33 μL dNTP stock (110 μM each dGTP, dATP, dTTP, and 6 μM dCTP), 0.66 μL of extension buffer (1.3 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM MgCl2, 100 mM DTT) and 0.5 μL [α-32P]dCTP. The reaction mix was incubated at 67°C for 30 min, at which time 1 μL of chase mix (1 mM each dGTP, dATP, dTTP, dCTP) was added, and incubation continued for a further 15 min. The reaction was stopped by precipitation of the DNA with 3 μL of 3 M NaAc (pH 5.4) and 90 μL of ethanol, resuspended into 10 μL of gel-loading buffer (7 M urea, 0.03% bromophenol blue dye), and the reaction products were separated on a 7 M urea 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel.

Secondary structure prediction

Secondary structure predictions were generated using the web implementation of the Mfold algorithm (Zucker et al. 1999), incorporating version 3.0 of the Turner rules (Mathews et al. 1999).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the BBSRC (K.A.S. and M.S. project grants and fellowship to A.E.W.) and the Wellcome Trust (S.A.M.). Catherine Jopling held a MRC studentship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5138804.

REFERENCES

- Belsham, G.J. and Jackson, R.J. 2000. Translation initiation on Picornavirus RNA. In Translational control of gene expression (eds. N. Sonenberg et al.), pp. 869–900. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Birrer, M.J., Dosaka, H., Segal, S., Nau, M., Degreve, J., Kaye, F., Sausville, E., and Minna, J. 1988a. Multiple L-myc messenger-RNA forms have transforming activity for primary rat embryo fibroblasts and an established rat fibroblast cell-line. Clinical Res. 36: A589–A589. [Google Scholar]

- Birrer, M.J., Segal, S., Degreve, J.S., Kaye, F., Sausville, E.A., and Minna, J.D. 1988b. L-Myc cooperates with Ras to transform primary rat embryo fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8: 2668–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood, E.M., Luscher, B., and Eisenman, R.N. 1992. Myc and Max associate in vivo. Genes & Dev. 6: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnal, S., Boutonnet, C., Prado-Lourenco, L., and Vagner, S. 2003. IRESdb: The internal ribosome entry site database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 427–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borman, A. and Jackson, R.J. 1992. Initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA: Mapping the internal ribosome entry site. Virology 188: 685–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer, L.M. and Dang, C.V. 2001. Translocations involving c-myc and c-Myc function. Oncogene 20: 5595–5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, S.A., Edelman, G.M., and Mauro, V.P. 2000. A 9-nt segment of a cellular mRNA can function as internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and when present in linked multiple copies greatly enhances IRES activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 1536–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell, M.J., Mitchell, S.A., Stoneley, M., MacFarlane, M., and Willis, A.E. 2000. Initiation of Apaf-1 translation by internal ribosome entry. Oncogene 19: 899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell, M.J., deSchoolmeester, M.L., Fraser, C.A., Pickering, B.M., Packham, G., and Willis, A.E. 2001. The p36 isoform of BAG-1 is translated by internal ribosome entry following heat shock. Oncogene 20: 4095–4100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creancier, L., Morello, D., Mercier, P., and Prats, A.C. 2000. Fibroblast growth factor 2 internal ribosome entry site (IRES) activity ex vivo and in transgenic mice reveals a stringent tissue-specific regulation. J. Cell Biol. 150: 275–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.R., Mitchell, S.A., Spriggs, K.A, Ostrowski J., Bomsztyk, K., Ostarek, D., and Willis A.E. 2003. Members of the poly (rC) binding protein family stimulate the activity of the c-myc internal ribosome entry segment in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene 22: 8012–8020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambidge, S.J. and Sarnow, P. 1991. Terminal 7-methyl-guanosine cap structure on the normally uncapped 5′ noncoding region of poliovirus messenger-RNA inhibits its translation in mammalian-cells. J. Virol. 65: 6312–6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton K.S., Mahon, K., Chin, L., Chiu, F.C., Lee, H.W., Peng, D., Morgenbesser, S.D., Horner, J., and DePinho, R.A. 1996. Expression and activity of L-Myc in normal mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 1794–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellen, C.U.T. and Sarnow, P. 2001. Internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNA molecules. Genes & Dev. 15: 1593–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling, C.L. and Willis, A.E. 2001. N-myc translation is initiated via an internal ribosome entry segment that displays enhanced activity in neuronal cells. Oncogene 20: 2664–2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M., Schallhorn, A., and Wurm, F.M. 1996. Transfecting mammalian cells: Optimization of critical parameters affecting calcium-phosphate precipitate formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 596–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, F., Battey, J., Nau, M., Brooks, B., Seifter, E., Degreve, J., Birrer, M., Sausville, E., and Minna, J. 1988. Structure and expression of the human L-myc gene reveal a complex pattern of alternative messenger-RNA processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8: 186–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Quesne, J.P.C., Stoneley, M., Fraser, G.A., and Willis, A.E. 2001. Derivation of a structural model for the c-myc IRES. J. Mol. Biol. 310: 111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legouy, E., DePinho, R., Zimmerman, K., Collum, R., Yancopoulos, G., Mitsock, L., Kriz, R., and Alt, F.W. 1987. Structure and expression of the murine L-myc gene. EMBO J. 6: 3359–3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, W., Leon, J., and Eilers, M. 2002. Contributions of myc to tumorigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1602: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, D.H., Sabina, J., Zuker, M., and Turner, D.H. 1999. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 288: 911–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S.A., Spriggs, K.A., Coldwell, M.J., Jackson, R.J., and Willis, A.E. 2003. The Apaf-1 internal ribosome entry segment attains the correct structural conformation for function via interactions with PTB and unr. Mol. Cell 11: 757–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanbru, C., Lafon, I., Audiger, S., Gensac, G., Vagner S., Huez, G., and Prats, A.-C. 1997. Alternative translation of the proto-oncogene c-myc by an internal ribosome entry site. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 32061–32066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nau, M.M., Brooks, B.J., Battey, J., Sausville, E., Gazdar, A.F., Kirsch, I.R., McBride, O.W., Bertness, V., Hollis, G.F., and Minna, J.D. 1985. L-myc, a new myc-related gene amplified and expressed in human small cell lung cancer. Nature 318: 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, S.K., Christiansen, J., Hansen, T.V., Larsen, M.R., and Nielsen, F.C. 2002. Human insulin-like growth factor II leader 2 mediates internal initiation of translation. Biochem. J. 363: 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelengaris, S., Khan, M., and Evan, G. 2002. c-Myc: More than just a matter of life and death. Nature Rev. Cancer 2: 764–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, B.M., Mitchell, S.A., Evans, J.R., and Willis, A.E. 2003. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein and poly (rC) binding protein interact with the Bag-1 IRES and stimulate its activity in vitro and in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 639–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijnbrand, R., vanderStraaten, T., vanRijin, P., Spaan, W., and Bredenbeek, P. 1997. Internal ribosome entry of ribosomes is directed by the 5′ non-coding region of classical swine fever virus and is dependent on the presence of an RNA pseudoknot upstream of the initiation codon. J. Virol. 71: 451–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sella, O., Gerlitz, G., Le, S., and Orna, E. 1999. Differentiation-induced internal tTranslation of c-sis mRNA: Analysis of the cis elements and their differentiation-linked binding to the hnRNP C protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 5429–5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, S., Moazed, D., and Noller, H.F. 1988. Structural analysis of RNA using chemical and enzymatic probing monitored by primer extension. Methods Enzymol. 164: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneley, M., Paulin, F.E.M., Le Quesne, J.P.C., Chappell, S.A., and Willis, A.E. 1998. C-myc 5′ untranslated region contains an internal ribosome entry segment. Oncogene 16: 423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneley, M., Subkhankulova, T., Le Quesne, J.P.C., Coldwell, M.J., Jopling, C.L., Belsham, G.J., and Willis, A.E. 2000. Analysis of the c-myc IRES: A potential role for cell-type specific trans-acting factors and the nuclear compartment. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 687–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieder, V. and Lutz, W. 2002. Regulation of N-myc expression in development and disease. Cancer Lett. 180: 107–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., Le, S., Ali, N., and Siddqui, A. 1995. An RNA pseudoknot is an essential structural element of the internal ribosome entry site located within the hepatitis C virus 5′ non-coding region. RNA 1: 526–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West, M.J., Sullivan, N.F., and Willis, A.E. 1995. Translational upregulation of the c-myc oncogene in Bloom’s syndrome cell lines. Oncogene 13: 2515–2524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, I., Fernandez, J., Liu, H.Y., Caprara, M., Komar, A.A., Koromilas, A.E., Zhou, L.Y., Snider, M.D., Scheuner, D., Kaufman, R.J., et al. 2003. The zipper model of translational control: A small upstream ORF is the switch that controls structural remodeling of an mRNA leader. Cell 113: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. and Sarnow, P. 1997. Location of the internal ribosome entry site in the 5′ non-coding region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein (BiP) mRNA: Evidence for specific RNA-protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 2800–2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, K.A., Yancopoulos, G.D., Collum, R.G., Smith, R.K., Kohl, N.E., Denis, K.A., Nau, M.M., Witte, O.N., Toran-Allerand, D., Gee, C.E., et al. 1986. Differential expression of myc family genes during murine development. Nature 319: 780–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker, M., Mathews, D.H., and Turner, D.H. 1999. Algorithms and thermodynamics for RNA secondary structure prediction: A practical guide. In RNA biochemistry and biotechnology, (eds. J. Barciszewski and B.F.C. Clark), pp. 11–43. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands.