Abstract

The invariant AGC triad of U6 snRNA plays an essential, unknown role in splicing. The triad has been implicated in base-pairing with residues in U2, U4, and U6. Through a genetic analysis in S. cerevisiae, we found that most AGC mutants are suppressed both by restoring pairing with U2, supporting the significance of U2/U6 helix Ib, and by destabilizing U2 stem I, indicating that this stem regulates helix Ib formation. Intriguingly, one of the helix Ib base pairs is required specifically for exon ligation, raising the possibility that the entirety of helix Ib is required only for exon ligation. We also found that U4 mutations that reduce complementarity in U4 stem I enhance U2-mediated suppression of an AGC mutant, suggesting that U4 stem I competes with the AGC-containing U4/U6 stem I. Implicating an additional, essential function for the triad, three triad mutants are refractory to suppression—even by simultaneous restoration of pairing with U2, U4, and U6. An absolute requirement for a purine at the central position of the triad parallels an equivalent requirement in a catalytically important AGC triad in group II introns, consistent with a role for the AGC triad of U6 in catalysis.

Keywords: U2, U4, U6, snRNA, splicing, spliceosome

INTRODUCTION

Pre-mRNA splicing, in which introns are excised from pre-mRNA to yield mRNA, is essential for the expression of most eukaryotic genes. The spliceosome, a ribonucleo-protein complex composed of five small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs)—U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6—and over 96 proteins (Staley and Guthrie 1998; Jurica and Moore 2003), catalyzes splicing. An intron recruits the spliceosome through conserved sequences at the 5′ and 3′ splice sites and the branch site. The spliceosome excises an intron by catalyzing two transesterification reactions. In the first reaction, the 2′ hydroxyl of an intronic adenosine, which forms the branch site, attacks the 5′ splice site, cleaving the 5′ exon from the intron and generating a branched lariat intermediate. In the second reaction, the 3′ hydroxyl of the freed 5′ exon attacks the 3′ splice site, excising the intron and ligating the exons. As the chemistry of pre-mRNA splicing is indistinguishable from group II intron self-splicing (Moore et al. 1993), the RNAs of the spliceosome may perform a critical function in catalysis (Villa et al. 2002).

Consistent with this hypothesis, in a catalytically active spliceosome U2 snRNA interacts with the branch site sequence, and U6 snRNA interacts with the 5′ splice site sequence (Staley and Guthrie 1998). Furthermore, base-pairing between U2 and U6 could serve to juxtapose the branch site adenosine with the 5′ splice site (Madhani and Guthrie 1992). Significantly, before the spliceosome recognizes an intron, U6 base pairs with U4, rather than U2, in a mutually exclusive manner (Brow and Guthrie 1988). Intron recognition triggers unwinding of U4/U6 and formation of U2/U6, activating the spliceosome for catalysis (Staley and Guthrie 1998).

Of the five snRNAs, U6 is the most attractive candidate for an snRNA that functions in catalyzing splicing. First, U6 has two highly conserved motifs—the ACAGAG box, which binds the 5′ splice site sequence (Kandels-Lewis and Séraphin 1993; Lesser and Guthrie 1993), and the AGC triad. Many mutations in these motifs are lethal, and many are deleterious for splicing in vitro. Phosphorothioate substitutions in the backbone of these motifs can also abolish splicing (Fabrizio and Abelson 1992; Yu et al. 1995). Second, a phosphate in the 3′ stem of U6 binds a key magnesium at a catalytic stage of splicing (Yean et al. 2000). Third, the catalytic domain V of group II introns shares structural similarities with U6 (for review, see Villa et al. 2002), including an AGC triad that is critical for catalysis (Boulanger et al. 1995; Peebles et al. 1995). Finally, base-paired U2/U6, in the absence of protein, promotes a reaction that shares similarities with splicing (Valadkhan and Manley 2001). In contrast to U6, the snRNAs U1 and U4 are not required for the chemistry of splicing (Yean and Lin 1991, 1996), and the region of U5 that interacts with pre-mRNA does not play an essential role in splicing in vitro (O’Keefe et al. 1996; Segault et al. 1999).

The AGC triad of U6 performs an essential function in splicing. Mutations at the first two positions of the AGC triad confer lethality (Madhani and Guthrie 1992; McPheeters 1996), whereas mutations at the final position cause a strong growth defect (McPheeters 1996). Mutations at all three positions are defective for splicing in vitro (Fabrizio and Abelson 1990; Wolff et al. 1994). In mammals, mutations at all three positions result in a defect in 5′ splice site cleavage (Wolff et al. 1994). In budding yeast, whereas substitutions of the G and C similarly result in a defect in 5′ splice site cleavage, base and phosphate substitutions of the A (Fabrizio and Abelson 1990, 1992) result in a defect in exon ligation. Yet, despite its significance, the essential function for the AGC triad of U6 remains to be determined.

The AGC triad may interact with the snRNAs in one or more mutually exclusive structures (Fig. 1 ▶). The AGC triad has been implicated in interactions with U2 to form helix Ib (Fig. 1A ▶; Madhani and Guthrie 1992) and with U6 to extend the 3′ stem (Fig. 1B ▶; Sun and Manley 1995). The AGC triad could also extend the 3′ stem in free U6. In addition, the triad is complementary to U4 in U4/U6 stem I (Fig. 1C ▶; Brow and Guthrie 1988). The AGC triad may also bind an additional component, forming a novel interaction.

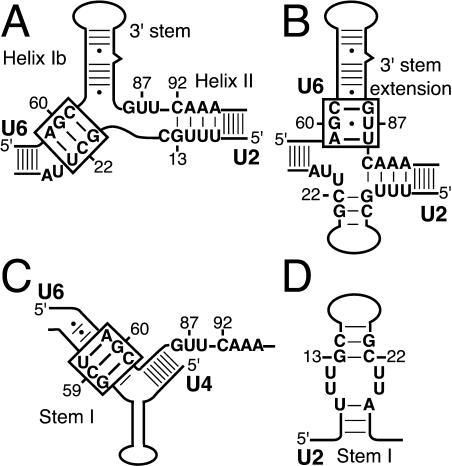

FIGURE 1.

The AGC triad is complementary to sequences within U2, U4, and U6. (A) U2/U6 helix Ib, in which the AGC triad is complementary to U2 (Madhani and Guthrie 1992). Helix Ib is mutually exclusive with U4/U6 stem I and U2 stem I. Helix II is also mutually exclusive with U2 stem I. (B) U6 3′ stem extension, in which the AGC triad is complementary to downstream residues in U6. The extension could form in base-paired U2/U6, as suggested by Sun and Manley (1995), or in free U6. (C) U4/U6 stem I, in which the AGC triad is complementary to U4 (Brow and Guthrie 1988). U4/U6 stem I is mutually exclusive with U4 stem I (Fig. 3C ▶). (D) U2 stem I. Throughout, structures containing the AGC triad are boxed.

To investigate the role of the AGC triad in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we performed a systematic compensatory analysis of the putative AGC-containing structures. We found genetic evidence for the entirety of U2/U6 helix Ib. In contrast, we found no significant evidence for base-pairing between the AGC triad and downstream U6 sequences. U4/U6 stem I is necessary, although not sufficient, for wild-type growth. Unexpectedly, mutations that destabilize U2 stem I (Fig. 1D ▶) suppress AGC triad mutants, suggesting that U2 stem I competes with helix Ib. Similarly, U4 stem I appears to compete with U4/U6 stem I. Significantly, three AGC mutants remain lethal even after simultaneous restoration of all three AGC-containing structures, suggesting that the AGC triad plays a critical, yet undiscovered, role beyond simply Watson–Crick base-pairing. Supporting a role for the AGC triad in catalysis, the central position of the triad must be a purine, paralleling an equivalent requirement in the AGC triad of the catalytic domain of group II introns.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

All but three mutations in the AGC triad of U6 are suppressed by reformation of U2/U6 helix Ib

Madhani and Guthrie (1992) provided genetic evidence for helix Ib by showing that U6 mutants -A59C and -A59G can be suppressed by compensatory mutations at U2-U23. Reciprocal suppression at this base pair and suppression at the other base pairs has not been reported, however, and in mammals the AGC triad has been implicated instead in base-pairing with downstream residues in U6 (Fig. 1B ▶). We now report evidence confirming the significance of all three base pairs in helix Ib.

Providing further evidence for the first base pair of helix Ib, we found that U2-U23 mutants can be suppressed reciprocally by U6-A59 mutations. Although U2-U23 mutants grow like wild-type yeast at or above 25°C (Madhani and Guthrie 1992), we found that these mutants, in a background lacking the large, nonessential, fungal-specific domain of U2 (U2ΔFD; Shuster and Guthrie 1988), grow poorly at 15°C. Furthermore, the growth defects of U2ΔFD-U23C and -U23G are suppressed by U6-A59 mutations that restore helix Ib (Fig. 2B ▶). As the U2-U23 mutants in full-length U2 are not similarly cold-sensitive (data not shown), these data also indicate that the fungal domain deletion enhances helix Ib mutants, suggesting a role for the fungal domain in stabilizing helix Ib. The suppression of U2ΔFD-U23 mutants by U6-A59 mutations is the first evidence that formation of helix Ib is a functionally important role of U2.

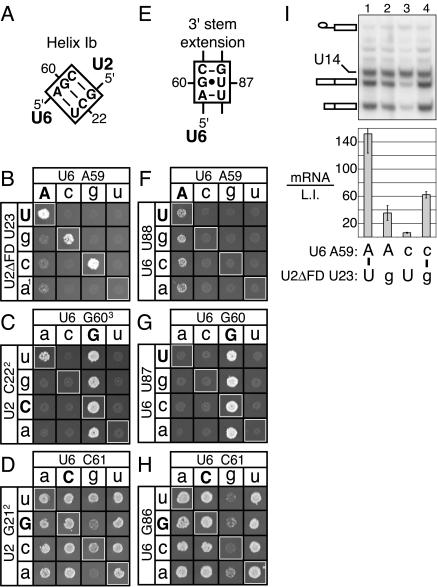

FIGURE 2.

Compensatory mutations in U2 but not in downstream residues of U6 can suppress the growth and splicing defects of AGC mutations. (A) Base-pairing of the AGC triad with U2 to form helix Ib, as proposed by Madhani and Guthrie (1992). (B–D) Compensatory analysis of helix Ib base pairs (B) between U6-A59 and U2-U23, (C) between U6-G60 and U2-C22, and (D) between U6-C61 and U2-G21. (E) Alternative base-pairing of the AGC triad with U6 to form the U6 3′ stem extension, as proposed by Sun and Manley (1995). (F–H) Compensatory analysis of U6 3′ stem extension base pairs (F) between U6-A59 and U6-U88, (G) between U6-G60 and U6-U87, and (H) between U6-C61 and U6-G86 in the presence of wild-type U2ΔFD (F) or wild-type, full-length U2 (G,H). The matrices show the growth phenotypes of single and double base pair mutations at 15°C (B,F) or 25°C (C,D,G,H) in strain yHM118. Wild-type residues are capitalized. White boxes highlight Watson–Crick combinations. The growth defects of U6-A59C and -A59G are suppressed by U2 compensatory mutations at all tested temperatures from 15°C to 37°C (data not shown; Madhani and Guthrie 1992). The growth defects of U6-G60A and -C61G are suppressed by U2 compensatory mutations at all tested temperatures except 34°C and 37°C (data not shown). (I) Compensatory analysis, by primer extension of splicing in vivo at 37°C, of the helix Ib base pair between U6-A59 and U2ΔFD-U23. The identities of the bases are shown below the graph. (Top) The RP51A lariat intermediate; the two RP51A mRNAs, which differ in their transcription start sites; and U14, which serves as an internal control, are highlighted. (Bottom) The mRNA:lariat intermediate ratio (mRNA/L.I.) is shown; the standard deviation is derived from the variance of two samples. 1Compensatory mutation U2-U12A maintains the U2 stem I bulge. 2Compensatory mutations at U2-G13 (C) or U2-C14 (D) preserve Watson–Crick base-pairing in U2 stem I. 3Compensatory mutations at U6-C92 preserve Watson–Crick base-pairing in U2/U6 helix II.

Base-pairing between U6-A59 and U2-U23 is not sufficient, however, as one Watson–Crick combination fails to support growth. Specifically, although Madhani and Guthrie (1994) showed that U6 mutants -A59C and -A59G are suppressed by compensatory mutations at U2-U23, suppression of U6-A59U by U2-U23A was not observed (cf. Fig. 2B ▶). The failure to suppress U6-A59U could result from misfolding or from a failure to satisfy an additional role for U6-A59. We have found no evidence that U6-A59U base pairs aberrantly with the bulge in U2/U6 helix I or that U2-U23A base pairs aberrantly within U2 stem I (data not shown). Although we cannot exclude other aberrant conformations, we favor the hypothesis that U6-A59 plays a role distinct from its function in base-pairing with U2. Notably, A59C, which completely disrupts pairing within helix Ib, is sick but viable, whereas A59G, which retains a wobble pair within helix Ib, is lethal (Madhani and Guthrie 1992). The viability of A59C, which in the syn conformation can mimic adenosine (see below), and the lethality of U6-A59U are consistent with an essential role, distinct from helix Ib formation, for the adenine of the AGC triad.

Providing evidence for the second base pair of helix Ib, we found that a purine substitution at U6-G60, the triad residue least tolerant to mutation (Madhani and Guthrie 1992), is suppressed by reformation of helix Ib. Specifically, U2-C22U suppresses the lethality of U6-G60A (Fig. 2C ▶, upper left). To maintain the integrity of U2 stem I and U2/U6 helix II (Fig. 1D ▶ and Fig. 1A ▶, respectively) in this double mutant, we included mutations U2-G13A and U6-C92U. Suppression of U6-G60A requires the maintenance of helix II (data not shown), indicating that helix Ib is sensitive to the stability of helix II (cf. Field and Friesen 1996). In contrast to U6-G60A, pyrimidine mutations at G60 cannot be suppressed by restoration of U2/U6 helix Ib (Fig. 2C ▶). Although we cannot rule out that these lethal AGC mutants are not suppressible for trivial reasons such as reduced levels of U6, we do find that severe, yet viable, mutations of the AGC triad do not affect U6 snRNA levels (data not shown). Just as the adenine of the AGC triad appears to function beyond helix Ib formation, these allelic constraints suggest that the guanine of the AGC triad serves an additional, purine-dependent role in splicing that is distinct from its role in helix Ib formation.

Providing evidence for the third helix Ib base pair, we found that all three U6-C61 mutations are suppressed by U2-G21 compensatory mutations that restore helix Ib. For instance, when stem I is maintained, U6-C61G is suppressed by the temperature-sensitive mutant U2-G21C, which reforms a Watson–Crick base pair, and by U2-G21U, which forms a wobble in helix Ib (Fig. 2D ▶). In addition, the mild temperature sensitivities of U6-C61A and -C61U are suppressed by compensatory mutations at U2-G21 (data not shown). We conclude that the primary function of the C of the AGC triad is to base pair with U2. Still, given the strict conservation of the C of the AGC triad (Gu et al. 1998), we anticipate that this C, as for the A and the G of the AGC triad, likely plays an additional role beyond helix Ib formation under certain conditions.

The role of the AGC triad in base-pairing with U2 appears to function redundantly with the additional, essential role of the AGC triad. Although some AGC triad mutations are sick or lethal, consistent with the importance of helix Ib, all U2 mutations that disrupt helix Ib are viable (Fig. 2C,D ▶; data not shown; Madhani and Guthrie 1992), indicating that helix Ib is nonessential. Field and Friesen (1996) found that U2 mutations in helix Ib and helix II are synthetically lethal, suggesting that helix Ib merely serves a function redundant to that of helix II. Restoration of helix Ib, however, is sufficient to suppress most AGC mutants, indicating that helix Ib becomes essential when a critical role of the AGC triad is compromised. We conclude that helix Ib reinforces this essential function of the AGC triad (discussed below).

We have begun an investigation to determine which stage in splicing requires helix Ib, and we found that the helix Ib base pair between U6-A59 and U2-U23 is required specifically for exon ligation. The U6-A59C allele (Fig. 2I ▶; cf. Fabrizio and Abelson 1990) and the U2ΔFD-U23C and -U23G alleles (Fig. 2I ▶; Madhani and Guthrie 1992) show reduced mRNA levels and increased lariat intermediate levels, indicating a defect in exon ligation. Importantly, combining U6-A59C and U2-U23G to restore helix Ib results in mutual suppression of their exon ligation defects. We conclude that the adenosine of the AGC triad functions in exon ligation, in part, by base-pairing within U2/U6 helix Ib. Because the first-step defect observed for mutations in the last two positions of the AGC triad (Fabrizio and Abelson 1990) may reflect a defect in formation of the U6 3′ stem or U4/U6 stem I (Fig. 1 ▶), rather than helix Ib, it remains to be determined whether the other base pairs in helix Ib are required for 5′ splice site cleavage or exon ligation. We are currently distinguishing between these possibilities in vitro.

Restoring the 3′ stem of U6 fails to suppress AGC triad mutations

As restoration of U2/U6 helix Ib is not sufficient to suppress three AGC mutants and the phenotypes of helix Ib mutants are asymmetric (Fig. 2B–D ▶), the AGC triad likely plays a critical role beyond helix Ib formation. For example, the AGC triad may also extend the 3′ stem of U6 (Fig. 1B ▶). Indeed, in mammals, where evidence for helix Ib has been lacking, suppression of several mutations in the AGC triad by downstream U6 mutations (Sun and Manley 1995) has suggested a critical function for the AGC triad in extending the 3′ stem of U6. In yeast, however, we do not observe significant suppression by any downstream U6 mutations (Fig. 2F–H ▶). Furthermore, compensatory mutations at U6-G86 enhance, rather than suppress, U6-C61 mutations; for example, at 25°C, where U6-G86C grows well and U6-C61G grows slowly, the double mutant does not grow at all (Fig. 2H ▶). These in vivo results are consistent with in vitro studies that similarly failed to find evidence for the 3′ stem extension (Ryan and Abelson 2002). Finally, U6 compensatory mutations fail to synergize with U2 compensatory mutations in suppressing AGC mutants (data not shown). We conclude that formation of the U6 3′ stem extension is not an important function of the AGC triad in yeast.

Although the AGC triad may function through alternative structures in the yeast and mammalian systems, formation of U2/U6 helix Ib may also be important in the mammalian system. First, the apparent discrepancies between the yeast (this work; Madhani and Guthrie 1992; Ryan and Abelson 2002) and mammalian (Sun and Manley 1995) systems may simply reflect differing rate-limiting steps during splicing. Second, although double mutations in the last two positions of the AGC triad in the mammalian system are not suppressed by compensatory U2 mutations (Sun and Manley 1995), tests for suppression of single mutations in these positions have not yet been reported. Conservation and cross-linking in the U12-dependent spliceosome (Tarn and Steitz 1996; Frilander and Steitz 2001) further support the significance of helix Ib. Significantly, the formation of helix Ib requires unwinding of the upper portion of U2 stem I, whereas formation of the U6 3′ stem extension does not. Thus, helix Ib formation necessitates a significant rearrangement in the activation of the spliceosome, suggesting that U2 stem I is a potential target for one of the spliceosomal DExD/H-box ATPases (for review, see Silverman et al. 2003).

Restoring all AGC-containing structures fails to suppress three lethal AGC mutants

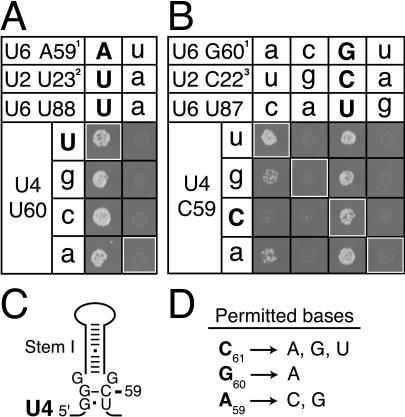

As restoration of both U2/U6 helix Ib and the U6 3′ stem fails to suppress three lethal mutations in the AGC triad (data not shown), the triad likely interacts with another component. U4 is a candidate, as the AGC triad is complementary to U4 within U4/U6 stem I (Fig. 1C ▶; Brow and Guthrie 1988). Reformation of U4/U6 stem I alone via U4 compensatory mutations is not sufficient to suppress any AGC triad mutant (data not shown). Thus, we tested whether restoration of all three AGC-containing structures can augment or confer suppression of triad mutants (Fig. 3A,B ▶). We found that a compensatory mutation in U4 does augment suppression by U2. Specifically, although the combination of U2 and U6 compensatory mutations alone fails to suppress U6-G60A at 37°C, the addition of U4-C59U confers wild-type growth (Fig. 3B ▶). These data support the importance of U4/U6 stem I formation.

FIGURE 3.

Compensatory mutations in U2, U4, and U6 fail to suppress three lethal AGC mutants. (A,B) Compensatory analysis, by growth, of the U4/U6 stem I base pair (A) between U6-A59 and U4-U60 and (B) between U6-G60 and U4-C59. Helix Ib and the U6 3′ stem, including the wobble between U6-G60 and U6-U87, are maintained in each experiment. The matrices are labeled as in Figure 2 ▶ and show growth phenotypes at 37°C in yJPS628. (C) Proposed structure of U4 stem I (Myslinski and Branlant 1991), which is mutually exclusive with the interaction between the AGC triad and U4. (D) Summary of AGC mutations that are viable alone or in the presence of compensatory U2 mutations. 1Compensatory mutations at U6-A93 (A) or at U6-C92 (B) maintain Watson–Crick base pairing in U2/U6 helix II. 2Mutation U2-U12A maintains the U2 stem I bulge. 3Compensatory mutations at U2-G13 maintain Watson–Crick base-pairing in U2 stem I.

The U4/U6 interaction, however, does not account for the lethality of AGC mutants refractory to suppression. Even in the presence of U2, U4, and U6 compensatory mutations, the triad mutants U6-A59U, -G60C, and -G60U are lethal (Fig. 3A,B ▶). Furthermore, the severity of mutations in vivo parallels their splicing defects in vitro (Fabrizio and Abelson 1990). Consistent with the strict conservation of the specific sequence of the AGC triad, these results suggest that U6-A59 and -G60 of the AGC triad perform a function beyond simply base-pairing with these snRNAs. We favor the hypothesis that the AGC triad interacts with yet another component, such as a critical nucleotide or an essential metal ion.

Interestingly, a purine preference at the central position of the AGC triad is also observed in a similar structure in the catalytic domain of group II introns. In the group II intron aI5γ, all mutations of the central G of the AGC triad inhibit splicing, but an A•C wobble can substitute for the wild-type G•U wobble (Boulanger et al. 1995; Peebles et al. 1995). In the mammalian spliceosome, mutation of the central G of the AGC triad to an A has no effect on splicing in vivo, whereas mutation to a C or U completely inhibits splicing (Datta and Weiner 1993), consistent with a purine-dependent role for the guanosine. Curiously, however, in the mammalian spliceosome the C mutation can be suppressed by a downstream mutation in U6 (Sun and Manley 1995), possibly reflecting different rate-limiting steps in yeast and mammalian splicing. Still, a purine-dependent function for the central residue of the AGC triad is implicated for both the yeast spliceosome and group II introns, consistent with a common, RNA-based mechanism for the catalysis of splicing.

The partial redundancy between the essential, unknown function of the AGC triad and U2/U6 helix Ib (Fig. 2B–D ▶; Madhani and Guthrie 1992) suggests that the essential function acts within the context of helix Ib. For example, both the helical configuration of helix Ib and the specific major groove functionalities of the AGC triad could contribute simultaneously and redundantly to the binding of a base or an important metal. Significantly, mutation of the helix that includes the AGC triad in domain V of group II introns exhibits a similar redundancy between the helical context and the identity of the AGC triad (Boulanger et al. 1995; Peebles et al. 1995). As the functional groups on the major groove face of the AGC triad in group II introns perform a catalytic role in splicing (Konforti et al. 1998), this parallel suggests that the major groove face of the U6 AGC triad, within the context of helix Ib, also plays a catalytic role in splicing.

The permitted mutations in the AGC triad (Fig. 3D ▶) are consistent with a role for the major groove face of the AGC triad. The purine requirement at U6-G60 (Fig. 2C ▶) suggests that functional groups common to purines, such as the N7, in the major groove, and/or the N3, in the minor groove, play an important role at the central G. As the major groove face of adenosine can be mimicked by cytosine in the syn conformation, the tolerance of the U6-A59C mutation (Fig. 4A ▶; Madhani and Guthrie 1992) suggests that the N6 and N7 of U6-A59 play an important role in the major groove of helix Ib. Consistent with the importance of N7, guano-sine is tolerated at U6-A59 when base paired to U2 and, consistent with the importance of N6 and/or N7, uracil is never tolerated (Figs. 2B ▶, 3A ▶). Intriguingly, the major groove face of helical, tandem purines has been recognized crystallographically as a metal-binding motif (Wedekind and McKay 2003). Thus, the tandem purines of the AGC triad, within the context of helix Ib, could coordinate one of the catalytically important metals required for leaving-group stabilization during pre-mRNA splicing (Sontheimer et al. 1997; Gordon et al. 2000). We are currently performing in vitro experiments to elucidate the additional, essential role of the AGC triad.

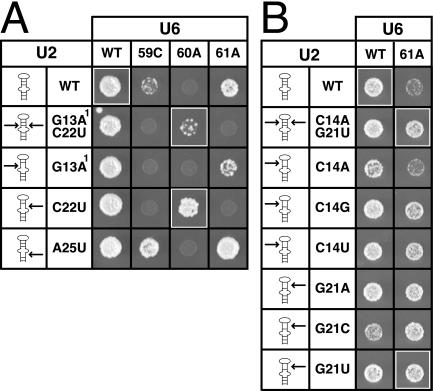

FIGURE 4.

Mutations that destabilize U2 stem I suppress AGC mutants. (A) Suppression of U6-A59C, -G60A, and -C61A by mutations that destabilize U2 stem I. (B) Suppression of U6-C61A by additional mutations that destabilize U2 stem I. The matrices are labeled as in Figure 2 ▶ and show the growth phenotypes at 34°C in yHM118. Arrows mark the position of nucleotide changes in U2 stem I. 1Compensatory mutation U6-C92U maintains U2/U6 helix II in the presence of the U2-G13A mutation.

Noncompensatory, weak suppressors of AGC mutants

We found that mutations that disrupt U4 stem I (Fig. 3C ▶; Myslinski and Branlant 1991) can contribute to suppression of an AGC triad mutant, which disrupts the mutually exclusive U4/U6 stem I. Specifically, any mutation at U4-C59 suppresses U6-G60A at 37°C (Fig. 3B ▶) in the context of the U2 compensatory mutation that alone suppresses U6-G60A at lower temperatures (Fig. 2C ▶). Although only the compensatory U4 allele C59U, which restores U4/U6 stem I, suppresses U6-G60A strongly, U4-C59A and -C59G suppress U6-G60A weakly (Fig. 3B ▶). As wild-type U4-C59 stabilizes U4 stem I, the U4-C59 mutations likely weaken U4 stem I, thereby promoting the interaction of the AGC triad of U6 with U4. These data suggest that U4 stem I antagonizes U4/U6 formation and that the interaction between the AGC triad and U4 helps drive U4/U6 formation.

Mutations that destabilize U2 stem I, which is mutually exclusive with helix Ib, also weakly suppress AGC triad mutants. Surprisingly, we found that U6-G60A is suppressed more robustly by U2-C22U, which restores helix Ib but disrupts U2 stem I, than by U2-C22U/G13A, which restores helix Ib and maintains U2 stem I (Fig. 4A ▶). Suppression of G60A, although enhanced by disruption of U2 stem I, requires maintenance of helix Ib. Other AGC mutants, however, are suppressed by disruption of U2 stem I alone in the absence of helix Ib repair. Specifically, each of the stem I-disrupting mutations U2-C14G, -C14U, -G21A, -G21C, -G21U, and -A25U suppresses the mutant U6-C61A (Fig. 4A,B ▶); some of these U2 alleles, such as U2-G21U and -A25U, also suppress U6-C61G and -C61U growth defects (data not shown). At 15°C, U2-G21U, which maintains helix Ib, suppresses U6-C61A more robustly than G21A or G21C (data not shown), underscoring the importance of helix Ib; additionally, U2 mutations that disrupt a second base pair within helix Ib, such as U2-C22U, are synthetically lethal with C61A (Fig. 4A ▶). The mutation U2-A25U also suppresses the mutant U6-A59C (Fig. 4A ▶). These results indicate that U2 stem I competes specifically with U2/U6 helix Ib (cf. Wu and Manley 1992), suggesting that U2 stem I unwinding may be regulated to control activation of the spliceosome.

In summary, we have shown that the AGC triad, in forming U2/U6 helix Ib, forms an important interaction with U2. We also found that formation of helix Ib is coupled to U2 stem I unwinding, suggesting a mechanism for regulating the function of the AGC triad. Additionally, our data indicate that the sequence tolerance of the AGC triad in U6 and in group II introns is similar. Finally, we found that the AGC triad functions beyond helix Ib formation in an essential role that may be involved in the catalysis of splicing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids

yJPS628 (MATa ade2-101; his3Δ200; leu2Δ1; lys2-801; trp1Δ63; ura3-52; snr6::LEU2; snr14::KanMX4; snr20::LYS2; [pJPS467]) was derived from yHM118 (Madhani and Guthrie 1994). pU2U6U in yHM118 was exchanged for pJPS467, and the chromosomal copy of SNR14 was disrupted with KanMX4 (Wach et al. 1994). To make pJPS467, we amplified wild-type U4 from a pSE362-derived vector (Madhani et al. 1990) by PCR to add flanking XbaI sites (primers 5′-CCCCTCTAGAATCATAAGTGCGTTCGAGGA ATAC-3′ and 5′-CCCCTCTAGAGAATTCGGTGAAAAAGAAAA GAAAAATATGG-3′), and cloned the digested product into the XbaI site of pU2U6U.

pSX6 (Madhani and Guthrie 1992) and a pSE362-based plasmid (pJPS216; Shuster and Guthrie 1988) were modified by QuikChange mutagenesis (Stratagene) to create U6 and full-length U2 mutant alleles, respectively. pES143 (Shuster and Guthrie 1988) was modified by QuikChange to create the wild-type and mutant U2ΔFD alleles by deleting the nonnative residue U2-T6 and introducing the appropriate mutations. To create pJPS464, we amplified wild-type U4 from a pSE362-derived vector (Madhani et al. 1990) by PCR to add flanking SacI and AvaI sites (primers 5′-CCCCAAGAGCTCATCATAAGTGCGTTCGAGGAA TAC-3′ and 5′-CCCCGGCTCGAGGAATTCGGTGAAAAAGAAA AGAAAAATATGG-3′), and cloned the digested product into the same sites in pASZ11 (Stotz and Linder 1990). U4-U60G, generated by QuikChange mutagenesis of pyU4, and the other U4 mutants (Madhani et al. 1990) were subcloned similarly into pASZ11. All PCR products were verified by sequencing.

Growth assays

To combine U2 and U6 alleles, we cotransformed yHM118 with pJPS216 and pSX6 variants. To combine U2, U4, and U6 alleles, we cotransformed yJPS628 with pJPS216, pSX6, and pJPS464 variants. Transformations were plated on media that selected for both the transformed and resident wild-type plasmids. Cells were grown overnight in liquid media selecting for all plasmids. Overnight cultures were diluted in rich media and grown for 3.5 doublings at 30°C. Cultures were diluted to equivalent optical densities and spotted onto media containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA; Sikorski and Boeke 1991). Growth phenotypes were assayed at 15°, 20°, 25°, 30°, 34°, and 37°C for 2–15 d.

Primer extension analysis

Cotransformants were streaked onto 5-FOA media and colony-purified on rich media. Cells were grown in rich media at 30°C and harvested during log phase after a 4-h shift to 37°C. Total RNA was isolated, and specific RNA species were assayed by primer extension (Stevens et al. 2002) using 32P-end-labeled primers complementary to the 3′ exon of RP51A (5′-CTTAGAAGCACGC TTGACGG-3′) and to U14 (5′-ACGATGGGTTCGTAAGCGTAC TCCTACCGTGG-3′). Products were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, developed by PhosphorImager, and quantitated by ImageQuant 1.2 (Molecular Dynamics).

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Piccirilli, Erik Sontheimer, Janice Pellino, and Rabiah Mayas for critical reading of the manuscript; Christine Guthrie and Peter Philippsen for strains and plasmids; Martha Norman, Valerie Shaw, and Channon Jordan for technical assistance; and the members of the Staley lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant GM62264 to J.P.S.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.7310704.

REFERENCES

- Boulanger, S.C., Belcher, S.M., Schmidt, U., Dib-Hajj, S.D., Schmidt, T., and Perlman, P.S. 1995. Studies of point mutants define three essential paired nucleotides in the domain 5 substructure of a group II intron. Mol. Cell Biol. 15: 4479–4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brow, D.A. and Guthrie, C. 1988. Spliceosomal RNA U6 is remarkably conserved from yeast to mammals. Nature 334: 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta, B. and Weiner, A.M. 1993. The phylogenetically invariant ACAGAGA and AGC sequences of U6 small nuclear RNA are more tolerant of mutation in human cells than in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 13: 5377–5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio, P. and Abelson, J. 1990. Two domains of yeast U6 small nuclear RNA required for both steps of nuclear precursor messenger RNA splicing. Science 250: 404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio, P. and Abelson, J. 1992. Thiophosphates in yeast U6 snRNA specifically affect pre-mRNA splicing in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 20: 3659–3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field, D.J. and Friesen, J.D. 1996. Functionally redundant interactions between U2 and U6 spliceosomal snRNAs. Genes & Dev. 10: 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frilander, M.J. and Steitz, J.A. 2001. Dynamic exchanges of RNA interactions leading to catalytic core formation in the U12-dependent spliceosome. Mol. Cell 7: 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, P.M., Sontheimer, E.J., and Piccirilli, J.A. 2000. Metal ion catalysis during the exonligation step of nuclear pre-mRNA splicing: Extending the parallels between the spliceosome and group II introns. RNA 6: 199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J., Chen, Y., and Reddy, R. 1998. Small RNA database. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 160–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurica, M.S. and Moore, M.J. 2003. Pre-mRNA splicing: Awash in a sea of proteins. Mol. Cell 12: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandels-Lewis, S. and Séraphin, B. 1993. Involvement of U6 snRNA in 5′ splice site selection. Science 262: 2035–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konforti, B.B., Abramovitz, D.L., Duarte, C.M., Karpeisky, A., Beigelman, L., and Pyle, A.M. 1998. Ribozyme catalysis from the major groove of group II intron domain 5. Mol. Cell 1: 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser, C.F. and Guthrie, C. 1993. Mutations in U6 snRNA that alter splice site specificity: Implications for the active site. Science 262: 1982–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani, H.D. and Guthrie, C. 1992. A novel base-pairing interaction between U2 and U6 snRNAs suggests a mechanism for the catalytic activation of the spliceosome. Cell 71: 803–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1994. Randomization-selection analysis of snRNAs in vivo: Evidence for a tertiary interaction in the spliceosome. Genes & Dev. 8: 1071–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani, H.D., Bordonne, R., and Guthrie, C. 1990. Multiple roles for U6 snRNA in the splicing pathway. Genes & Dev. 4: 2264–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPheeters, D.S. 1996. Interactions of the yeast U6 RNA with the pre-mRNA branch site. RNA 2: 1110–1123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.J., Query, C.C., and Sharp, P.A. 1993. Splicing of precursors to mRNA by the spliceosome. In The RNA World. (eds. R.F. Gesteland and J.F. Atkins), pp. 279–307. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Myslinski, E. and Branlant, C. 1991. A phylogenetic study of U4 snRNA reveals the existence of an evolutionarily conserved secondary structure corresponding to “free” U4 snRNA. Biochimie 73: 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe, R.T., Norman, C., and Newman, A.J. 1996. The invariant U5 snRNA loop 1 sequence is dispensable for the first catalytic step of pre-mRNA splicing in yeast. Cell 86: 679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peebles, C.L., Zhang, M., Perlman, P.S., and Franzen, J.S. 1995. Catalytically critical nucleotide in domain 5 of a group II intron. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92: 4422–4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, D.E. and Abelson, J. 2002. The conserved central domain of yeast U6 snRNA: Importance of U2-U6 helix Ia in spliceosome assembly. RNA 8: 997–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segault, V., Will, C.L., Polycarpou-Schwarz, M., Mattaj, I.W., Branlant, C., and Lührmann, R. 1999. Conserved loop I of U5 small nuclear RNA is dispensable for both catalytic steps of pre-mRNA splicing in HeLa nuclear extracts. Mol. Cell Biol. 19: 2782–2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster, E.O. and Guthrie, C. 1988. Two conserved domains of yeast U2 snRNA are separated by 945 nonessential nucleotides. Cell 55: 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R.S. and Boeke, J.D. 1991. In vitro mutagenesis and plasmid shuffling: From cloned gene to mutant yeast. In Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology (eds. C. Guthrie and G.R. Fink), pp. 302–318. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Silverman, E., Edwalds-Gilbert, G., and Lin, R.-J. 2003. DExD/H-box proteins and their partners: Helping RNA helicases unwind. Gene 312: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer, E.J., Sun, S., and Piccirilli, J.A. 1997. Metal ion catalysis during splicing of premessenger RNA. Nature 388: 801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley, J.P. and Guthrie, C. 1998. Mechanical devices of the spliceosome: Motors, clocks, springs, and things. Cell 92: 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, S.W., Ryan, D.E., Ge, H.Y., Moore, R.E., Young, M.K., Lee, T.D., and Abelson, J. 2002. Composition and functional characterization of the yeast spliceosomal pentasnRNP. Mol. Cell 9: 31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotz, A. and Linder, P. 1990. The ADE2 gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Sequence and new vectors. Gene 95: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.S. and Manley, J.L. 1995. A novel U2-U6 snRNA structure is necessary for mammalian mRNA splicing. Genes & Dev. 9: 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarn, W.-Y. and Steitz, J.A. 1996. Highly diverged U4 and U6 small nuclear RNAs required for splicing rare AT-AC introns. Science 273: 1824–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadkhan, S. and Manley, J.L. 2001. Splicing-related catalysis by protein-free snRNAs. Nature 413: 701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa, T., Pleiss, J.A., and Guthrie, C. 2002. Spliceosomal snRNAs: Mg2+-dependent chemistry at the catalytic core? Cell 109: 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach, A., Brachat, A., Pohlmann, R., and Philippsen, P. 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10: 1793–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedekind, J.E. and McKay, D.B. 2003. Crystal structure of the leadzyme at 1.8 Å resolution: Metal ion binding and the implications for catalytic mechanism and allo site ion regulation. Biochemistry 42: 9554–9563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, T., Menssen, R., Hammel, J., and Bindereif, A. 1994. Splicing function of mammalian U6 small nuclear RNA: Conserved positions in central domain and helix I are essential during the first and second step of pre-mRNA splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91: 903–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. and Manley, J.L. 1992. Multiple functional domains of human U2 small nuclear RNA: Strengthening conserved stem I can block splicing. Mol. Cell Biol. 12: 5464–5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yean, S.L. and Lin, R.-J. 1991. U4 small nuclear RNA dissociates from a yeast spliceosome and does not participate in the subsequent splicing reaction. Mol. Cell Biol. 11: 5571–5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1996. Analysis of small nuclear RNAs in a precatalytic spliceosome. Gene Expr. 5: 301–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yean, S.L., Wuenschell, G., Termini, J., and Lin, R.-J. 2000. Metalion coordination by U6 small nuclear RNA contributes to catalysis in the spliceosome. Nature 408: 881–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.T., Maroney, P.A., Darzynkiwicz, E., and Nilsen, T.W. 1995. U6 snRNA function in nuclear pre-mRNA splicing: A phosphorothioate interference analysis of the U6 phosphate backbone. RNA 1: 46–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]