Abstract

Small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) constitute newly discovered noncoding small RNAs, most of which function in guiding modifications such as 2′-O-ribose methylation and pseudouridylation on rRNAs and snRNAs. To investigate the genome organization of Trypanosoma brucei snoRNAs and the pattern of rRNA modifications, we used a whole-genome approach to identify the repertoire of these guide RNAs. Twenty-one clusters encoding for 57 C/D snoRNAs and 34 H/ACA-like RNAs, which have the potential to direct 84 methylations and 32 pseudouridines, respectively, were identified. The number of 2′-O-methyls (Nms) identified on rRNA represent 80% of the expected modifications. The modifications guided by these RNAs suggest that trypanosomes contain many modifications and guide RNAs relative to their genome size. Interestingly, ~40% of the Nms are species-specific modifications that do not exist in yeast, humans, or plants, and 40% of the species-specific predicted modifications are located in unique positions outside the highly conserved domains. Although most of the guide RNAs were found in reiterated clusters, a few single-copy genes were identified. The large repertoire of modifications and guide RNAs in trypanosomes suggests that these modifications possibly play a central role in these parasites.

Keywords: snoRNA, trypanosomatids, C/D, H/ACA, pseudouridines, 2′-O-methyls

INTRODUCTION

Most of the stable RNA molecules including rRNAs and snRNAs undergo post-transcriptional modifications. The two major modifications, 2′-O-methylation and pseudouridylation, are very prevalent in rRNAs and small nuclear RNAs (Weinstein and Steitz 1999; Bachellerie et al. 2002; Kiss 2002; Decatur and Fournier 2003). In eukaryotes as well as in Archaea the modifications are guided by two types of small RNAs that dictate the exact sites of modification by the formation of a specific duplex with their target RNAs. In eukaryotes these RNAs are localized mostly in the nucleolus and are termed small nucleolar RNAs. In Archaea these RNAs were termed sRNAs (Omer et al. 2000; Dennis et al. 2001).

The C/D snoRNAs that guide 2′-O-methylation are named after short sequence motifs, the C-box (RUGAUGA; R designates purine) and the D-box (CUGA). These boxes, together with the short sequences near the 5′ end and 3′ end of the RNA, are essential for their accumulation, processing, localization, and function (Cavaille and Bachellerie 1996; Xia et al. 1997; Lange et al. 1998; Watkins et al. 2002). Most of these snoRNAs contain, between the C and D motifs, sequences related to these boxes known as C′ boxes and D′ boxes. Four core proteins bind the C/D snoRNAs: fibrillarin or Nop1p in yeast, Nop56p, Nop58p, and 15.5 K or Snu13p in yeast. It was found that the region of perfect complementarity (10–21 nt) between the target RNA and the snoRNA lies upstream from the D or D′ sequences. The methylated nucleotide is always located 5 nt upstream from the D-box or D′ box within the domain of interaction between the snoRNA and the target. This is known as the +5 rule (Kiss-Laszlo et al. 1996). The C/D snoRNA usually carry domains complementary to two targets present upstream to the D-box and D′ box. Potentially these snoRNAs can guide the modifications on two sites (double guiders). In case only one of the sites is used for guiding modification, the snoRNA is a single guider. However, in several cases there are two sites that are complementary to the target RNA, but as in the case of U14, one of the guide sequences is essential for 18S processing, whereas the second one is essential for methylation (Li et al. 1997; Dunbar and Baserga 1998).

In most eukaryotes studied so far, the snoRNAs that govern pseudouridylation consist of two hairpin domains connected by a single-stranded hinge, the H (AnAnnA) domain, and a tail region, the ACA-box. Four core proteins, namely, Gar1p, Nop10p, Nhp2p, and Cbf5p/dyskerin, were identified in eukaryotic H/ACA snoRNPs. With the exception of Gar1p, all core proteins are essential for snoRNA stability. Two short rRNA recognition motifs of the snoRNA base pair, with rRNA sequences flanking the uridine to be converted to pseudouridine, have been characterized (Ganot et al. 1997; Tollervey and Kiss 1997). The pseudouridine is always located 14–16 nt upstream from the H-box or ACA-box of the snoRNA. In yeast and mammals, the two hairpin domains are essential for rRNA modification, even when the RNA contains a single guide sequence (Bortolin et al. 1999). The two major structural domains of the H/ACA snoRNA, the 5′ hairpin (hp) followed by the H-box and the 3′ hairpin followed by the ACA-box, share striking structural and functional similarities. Pseudouridylation pockets are found equally frequently in the 5′ or 3′ end of the molecule, and in several cases many snoRNAs can direct pseudouridylation of rRNA at two different positions (Ganot et al. 1997).

All snoRNA guiding modifications characterized so far are transcribed by RNA polymerase II, whereas snoRNAs involved in rRNA processing can also be transcribed in plants by RNA polymerase III (Brown et al. 2003a), and in trypanosomes U3 is transcribed by RNA polymerase III using a divergently transcribed tRNA as an extragenic promoter (Nakaar et al. 1994). Vertebrates, plants, and yeast contain independently transcribed snoRNA genes flanked by promoter, enhancer, and termination sequences (Brown et al. 2003a). In vertebrates, the majority of the snoRNAs that guide modifications are located within introns. The intronic snoRNAs are transcribed from the host gene promoters. In vertebrates and yeast having only a single snoRNA in any intron, the processing is largely splicing-dependent (Ooi et al. 1998; Filipowicz and Pogacic 2002).

Trypanosomes are unicellular parasitic protozoa that are the causative agent of several infamous parasitic diseases such as African trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma brucei, Chagas’ disease caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, and Leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania species. Trypanosomatids are well-known for harboring exotic and unique RNA processing events such as nuclear pre-mRNA trans-splicing (Liang et al. 2003a) and mitochondrial RNA editing (Simpson et al. 2003). In addition, the large rRNA subunit undergoes specific cleavages that yield two large rRNA molecules and four small RNAs, ranging in size from 220 to 76 nt (White et al. 1986).

Relatively little is known about snoRNAs in trypanosomatids. Early studies suggest the existence of ~100 2′-O-methylated nucleotides on the rRNA (Gray 1979). The first trypanosome C/D snoRNA (snoRNA-2) was identified in Leptomonas collosoma (Levitan et al. 1998). Later, snoRNAs and reiterated gene clusters encoding for snoRNAs were identified in T. brucei (Dunbar et al. 2000a,b). Whereas the trypanosome C/D snoRNA fit the prototype C/D snoRNA in eukaryotes and Archaea, the trypanosome H/ACA RNAs possess unique features. Most if not all of the these guide RNAs are single-hairpin RNAs and carry an AGA-box instead of an ACA-box (Uliel et al. 2004). After the discovery of the single-hairpin guide RNAs in trypanosomes, such guide RNAs were found in Archaea (Tang et al. 2002; Rozhdestvensky et al. 2003) and more recently in Euglena (Russell et al. 2004). Prior to this study, only ~20 C/D snoRNA and ~10 H/ACA-like RNAs were described in trypanosomatids and are listed in Uliel et al. (2004). The organization of trypanosome snoRNAs mostly resembles plants because the genes are clustered and each cluster carries a mixture of both C/D and H/ACA RNAs (Brown et al. 2003a; Uliel et al. 2004). The trypanosome snoRNAs are processed from long polycistronic transcripts (Xu et al. 2001; Liang et al. 2003b), but the machinery involved in this processing is currently unknown.

In this study, bioinformatics and experimental tools were used to describe on a genomic scale, the snoRNAs that guide methylation and pseudouridylation on rRNA in T. brucei. The data suggest that most but not all the snoRNAs are clustered in reiterated repeats that carry a mixed population of C/D and H/ACA-like RNAs. All the H/ACA-like RNAs that potentially can guide modification are single-hairpin RNAs. Predicting the modifications guided by these RNAs and using partial mapping data, we identified 84 2′-O-methyls (Nms) and 32 Ψs on rRNA, suggesting a high number of Nms on rRNA compared with their genome size. Many of these modifications are species-specific and enlarge a domain already rich with such modifications. However, of the trypanosome-specific modifications, 40% are also predicted to exist in unique positions outside the highly conserved domains. These numerous modifications increase the stability of the ribosomes and are perhaps beneficial in coping with the adverse conditions associated with the cycling of these parasites between the mammalian and insect hosts.

RESULTS

Using the bioinformatics approach to search for snoRNAs in T. brucei

Prior to this study, nine C/D snoRNAs were identified in L. collosoma and 22 C/D snoRNAs in T. brucei, and only nine H/ACA-like RNAs in L. collosoma and three in T. brucei were described (listed in Uliel et al. 2004). To perform a whole-genome search for both C/D and H/ACA-like RNAs in trypanosomes, we took advantage of specific characteristics of trypanosome snoRNAs that we have recently identified (Uliel et al. 2004). The majority of trypanosome snoRNA genes are characterized as follows: (1) the genes are organized in clusters that contain both C/D and H/ACA-like RNAs, (2) the snoRNA genes are repeated in the chromosome several times, and (3) the H/ACA-like RNAs have special trypanosome features. Most of these RNAs can be folded as a single hairpin and all carry an AGA-box at the 3′ end. These special characteristics guided us in searching for these RNAs in the T. brucei genome. To broaden the snoRNA collection, we developed an integrative bioinformatics approach to search the whole genome of T. brucei for snoRNAs. More specifically, we used the algorithm developed by Lowe and Eddy (SnoScan: http://rna.wustl.edu/snoRNAdb/code) to search the entire T. brucei genome for C/D snoRNAs (Lowe and Eddy 1999). In parallel, we searched for homologous noncoding regions of the two related trypanosomatid species T. brucei and T. cruzi. In addition, we scanned the genome for areas of tandem repeats using the Tandem Repeat Finder program (Benson 1999). Each of these methods individually yielded a high percentage of false-positive results. However, the results common to all the searches yielded only true positives (S. Uliel, X.-H. Liang, T. Doniger, S. Michaeli, and R. Unger, in prep.). Once a snoRNA cluster was identified, a manual search was performed to precisely determine the snoRNA content in each cluster. In addition, we searched for homologs to the T. brucei snoRNAs in Leishmania major, since we realized that in this species the content of the clusters is not 100% conserved (Uliel et al. 2004). This enabled us to identify novel snoRNAs that were not yet present in our collection and to find their cognate cluster in the T. brucei genome. This approach led to the finding of the TB10Cs4 cluster. The structure of the 21 clusters is presented in Figure 1 ▶. The clusters were named based on the chromosomal location. In each cluster, we indicate the identity of the C/D RNA with C and H/ACA-like RNA with H. The size of the RNA and the size of the intergenic region as well as the number of repeats within each cluster are indicated.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of snoRNA clusters in T. brucei. (A) The nomenclature of T. brucei snoRNA. (B) snoRNA clusters. The C/D snoRNAs are shown as light-shadowed boxes, whereas the H/ACA-like RNAs are in dark boxes. Thinner lines indicate an intergenic region, and their size is indicated above the line. The lengths of snoRNA genes (±3 bp) are indicated below the box. The number on the right side of each cluster indicates the times the cluster is repeated in the genome. The white boxes indicate the flanking protein. The small numbers below the name of each cluster indicate the position of the cluster in the genome database in the T. brucei GD release 3 (http://www.genedb.org/genedb/tryp/index.jsp).

The structure and gene organization of the snoRNA clusters

Most of the snoRNAs (80%) appear on chromosomes 8, 9, 10, and 11. A few clusters also appear on chromosomes 3, 5, and 6. We noted that snoRNA genes never appear on chromosomes 1, 2, 4, and 7, which carry rRNA repeats. The individual snoRNAs were designated as depicted in Figure 1A ▶ with the designation TB#Cs#C/H#. First, the chromosomal location is indicated (TB), next the number of clusters “walking” from 5′ to 3′ on the chromosome was determined (Cs#), and then the snoRNA was categorized as C or H, depending on whether it is a C/D or an H/ACA-like RNA. Finally, the number indicates the number of the specific RNA (C or H, separately) within the cluster. In these clusters, 57 C/D and 34 H/ACA-like RNAs were identified. The data as well as the previous results (Levitan et al. 1998; Dunbar et al. 2000a; Xu et al. 2001; Liang et al. 2004; Uliel et al. 2004) suggest that most snoRNA genes in trypanosomes are clustered.

The majority of the clusters are repeated in the chromosome, ranging from 1.4 to a maximum of 7.5. The last repeat is almost always not complete, that is, it lacks portions from its 3′ end. However, we also detected complete repeats that are repeated, seven and five times. All the snoRNA clusters identified in this study are flanked by protein-coding genes. We noticed that the 5′ upstream flanking protein is situated ~500 bp upstream from the beginning of the cluster, whereas the location of the 3′ flanking protein varies considerably and can be as short as 10–20 nt downstream from the end of cluster. These data suggest that the region upstream from the cluster may have “promoter-like” activity, as was recently demonstrated (Liang et al. 2004).

A second type of cluster are those clusters where not only the snoRNAs are repeated, but the repeat also includes a protein-coding gene. An example of such a cluster is TB9Cs4, which carries the protein glycerolkinase (GLK1) (Tb09.211.3560). This protein, along with its neighboring snoRNA, are repeated 5.4 times. The TB11Cs1 repeat also carries a protein (GP63). The cluster appears once carrying two copies of GP63 (Tb11.02.5640; Tb11.02.5630) at the 3′ end of the cluster. The second cluster also carries two GP63 proteins: Tb11.02.5620 and a truncated version of the protein (Tb11.02.5610).

Another type of snoRNA organization is the duplication of only a portion of a cluster, which is the case of TB5Cs1. Structurally, the cluster contains two copies of C/D (TB5Cs1C1), and again in the same chromosome, another copy of this C/D snoRNA exists. Moreover, the proteins flanking these snoRNAs are different. Another interesting cluster is TB8Cs3, which carries a full repertoire of snoRNA (three C/Ds and one H/ACA) and is also found consisting of only the two C/D snoRNAs. In each case, the snoRNA clusters are flanked by different sequences.

Expression of snoRNA genes

Primer extension was used to detect the expression of different snoRNA genes (TB9Cs2H1, TB6Cs1H2, TB6Cs1H4, TB10Cs3H1, TB9Cs2C5, and TB5Cs1C1). The results, presented in Figure2A ▶, indicate the expression of clusters 2, 3, 8, and 13. Since snoRNAs are transcribed as polycistronic transcripts, the expression of any snoRNA within a cluster suggests that this cluster is actively transcribed (Roberts et al. 1998; Dunbar et al. 2000a,b; Liang et al. 2001; Xu et al. 2001). Previous studies identified the expression of the following C/D snoRNAs: TB6Cs1C1, TB6Cs1C2, TB6Cs1C3, TB8Cs1C4, TB8Cs3C3, TB9Cs2C1, TB9Cs2C4, TB10Cs2C2, TB10Cs3C1, TB10Cs3C4, TB10Cs3C5, TB11Cs1C2, TB11Cs2C1, TB11Cs2C2, and TB11Cs3C2 (Dunbar et al. 2000a; see Table 1 ▶). Additionally, our previous study confirmed the expression of Leptomonas snoRNAs (Liang et al. 2001, 2004; Xu et al. 2001). The T. brucei homologs to these snoRNAs are TB5Cs1C1, TB9Cs1C1, TB9Cs4C1, TB9Cs4C2, TB11Cs4C2, and TB11Cs4C3 (see Table 1 ▶). Collectively, these data suggest the expression of 13 clusters: clusters 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, and 18. Whereas the study of Dunbar et al. (2000a) indicated the expression of only C/D snoRNAs, the data presented here suggest the expression of H/ACA-like RNAs. For instance, in cluster 4 the expression of two H/CAC-like TB6Cs1H2, Tb6Cs1H4 RNAs was confirmed, suggesting that, indeed, all the RNAs within a polycistronic transcript are most likely expressed. Note that the snoRNA precursors can easily be detected in steady-state RNA by RT-PCR both in L. collosoma and T. brucei (Xu et al. 2001; Liang et al. 2003b, 2004).

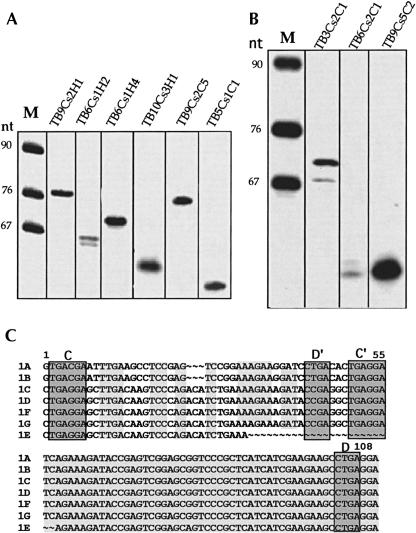

FIGURE 2.

Expression studies on the predicted snoRNAs. (A) Primer extension analysis of snoRNAs present in different clusters. Total RNA was subjected to primer extension with the following primers (50,000 cpm in each reaction): Tbsno-H1, 2-CH-2, 2-HH-3, and TB5H1 specific for the H/ACA-like snoRNAs TB9Cs2H1, TB6Cs1H2, TB6Cs2H4, and TB10Cs3H1, respectively. Primers TbsnoC4 and Tb5C1 were used to detect C/D snoRNAs TB9Cs2C5 and TB5Cs1C1, respectively. The identity of each snoRNA is indicated above the lane. (Lane M) A pBR322 MspI digest was used as a marker. (B) Expression studies on snoRNAs present in clusters with unique properties. Primer extension analyses were performed using primers TBcr03, TB6C2-A, and TB9Cs5-A, specific to TB3Cs2C1, TB6Cs2C1, and TB9Cs5C2, respectively. The extension product was analyzed on 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel. (Lane M) Labeled marker of a pBR322 MspI digest. The sizes are indicated in nucleotides. (C) Sequence alignment of different copies of TB3Cs2C1. The potential C/D and C′/D′ domains are boxed. The conserved sequences are shown in shadow. 1A–1G reflect the different copies of the same snoRNA present in the cluster. The missing nucleotides are shown as “~.” Sequence alignment was performed using the program Pileup from the GCG package.

TABLE 1.

The T. brucei C/D sno RNAs

| Name | Sequence | Homolog | Previous name or trypanosome homolog |

| TB3Cs2C1 | GTGACGAATTTGAAGCCTCCGAGTCCGGAAAGAAGGATCCTGACACTGAGGATCAGAAAGATACCGAGTCGGAGCGGTCCCGCTCATCATCGAAGAAGCCTGAGGA | ||

| TB5Cs1C1 | GTGATGAATTTTAAGCTTAGGACACCTTTGGACGCAGGGACCCTGCGATTGAAAACAGTGAAACTTGATCGATTCGTACACTGATTT | AtsnoR10 | LC-B2 |

| TB6Cs1C1 | AGCATGATGATCATACGTGCAATTCCTGTGGTATCTGAAAAATGCAATGACAGAAGAACTGCGACGATGCCTTCATACAAGGATTTACTGACT | TBR16 | |

| TB6Cs1C2 | CCAATGATGTTGTTATTTAATTATACACCTGATCATGTTGTTGATGAGAGGAAACGCTGAGGTG | TBR10 | |

| TB6Cs1C3 | GATGATGCTAACAATCGAGGCATTTGTATGATTTTCAAATGAATTAGGCATCCGTGCACTAAGCTACCTATCATAAGCACGGGACTGAT | SnR13 | TBR13 |

| TB6Cs2C1 | CGCTGATGAATTAATTTTTCTGAGTGTTTTCTTAGAGTTCCGTAACGGGCATGATAAGCACACAAATTATGAACCCTTTAACTCTGAGAG | SnR47 | |

| TB6Cs2C2 | AATGTTGATGAGAGGAACTTGTAAGTTTGATTCTTTCCTGAGGTAGTGTGTATTACGAAAATTAACTTGTGAGAAAGCATTCAAATGTTGTTTTGAAGG | ||

| TBCs1C1 | GTGTGTGATGTATATACGACTATGAACAACTCGTCAGAGTGCTATCTTTGATGATCACATACATTTTGCTTCCTCACTGACAA | ||

| TB8Cs1C2 | CACGGTGATGTTCAATACAATAACTGATGTAATGAGACCTAGTGGAATACTGCGGACACTTCTTGTTCTGAGCG | SnR51 | |

| TB8Cs1C3 | ACACATGATGAGCAGCAAAGAAAGGGAATCTCTTGTCGAGCTCAGGGAATGAATCCCAGTGGCGGTGACATGACAAACTTTGATATTACTATAATCCATTCTATTCTGTTACTGATGC | ||

| TB8Cs1C4 | TCCCTTGATGATTGTGGCAACTCTCCACGGAACTTATCTGACAAAATTTGCCTACGAACCTATTACCAAGGCTGAGGT | TBR15 | |

| TB8Cs2C0 | GCGCGTGATGAATAAATACAAACGACCAATAATCGGAAGCGTCAGTAACACCTCACGCATGACGCCACTTTGAATGCAATACTAATTATCTGACTC | ||

| TB8Cs2C1 | TACCTCGATGATGTGTATGAGAACAAGCATATGTCCGAGCTGACCACAATTGTGGCACAATGAGAGCATTACTCGAGTCCTTGAAAGCTGAGTG | SnR74 | |

| TB8Cs3C1 | GCCAGTGATTATACGTAATGTCTTTGCTACAGGTGATTGTACGATATGACCATACCGACTAAACCAACCGAGATCAATGAGGC | U24 | |

| TB8Cs3C2 | CGGTGTGATTACAGACAGGATGTAAGTGAGTCAATGTCAATATCTCCGTATTACACCATGAGGACTATTGTCCCCCGTGTCTGACCG | ||

| TB8Cs3C3 | ACACATGATGTCATTTCGTATTCTGCAATACTGACAATAACTTGAGCGAGACAAGACATATTTGACTACTGGCAACTGAAAC | AtsnoR39b | TBR14/Sn oRNA-2 |

| TB9Cs1C1 | CTTCGTGATGATCCCGCGAACTGAGTGTACCTTTTTTCAGCACTTTCGTGCAATGGAATGTAATGGCACGGTGCCCTCTTGTTGGGTGTACTGATA | LC-B5 | |

| TB9Cs2C1 | GCCCATGACGATAAACCACTTACGACGGTCTTATGACACACACCCGAACATGGATTGAGCACGAGTGTTACGATAGTTTCTGGGGCGCCGCACAACATTCCCGAGGC | SnR73 | TBR1 |

| TB9Cs2C2 | GTCAATGATGAGTCTGTCAAATCCGTGTTTCAGCTGAATTTATTTGATGCTGACATCAGTTAATTTTGTCTGTTTGACTTCTGAGTA | Snr68 | |

| TB9Cs2C3 | GTGGCCGATGATGGAAACTAGTTGAGCGTCCAAACATGTTCCGACGTCATATTCATGAGGGATCTATACAACACAAATCACCTTTCGGGTCTGATGG | Snr39b | |

| TB9Cs2C4 | GGGTGACGATGTACAATATGTTCAAATTGCACCGAGAACCTGTGAGGACACCATAACACAGACCTGCACTGAACCT | Snr56 | TBR8 |

| TB9Cs2C5 | GCCACTGATGAAAGAGCTTCCGATACCGCGTAGGCGGAACGGAAACACACTATGTCGATGCAACTGTGAACTCTATCTTTCGCTCCGAGCTGACGT | Snr60 | |

| TB9Cs2C6 | GCGTGTGATGAATACCTAATATAACAAATTAACAGCAACATCTGAACAGAACCCGTGACGCTAATATTGTTTCTGACGC | ||

| TB9Cs2C7 | CTACTTGATGACATCAATGGACTGGAGTCTCTGAGTGTATTTGAATGACAATAACCCATTTAAAGAATATTCTTCTTTCCCCGGCTGATGG | Snr78/190 | |

| TB9Cs3C1 | ATTACTTGATGTATAACACGATATTCAGGTAAAGATTATCAGGAGTAACTGACTGAGATAACATCATGCACCACTCTGACCA | SnR40 | |

| TB9Cs3C2 | CTCCATGATGCCATGACAAGACTATAAGAGCACAGTTTGAACTGACTTCACAAGACGGACGAGAACGTCGCTGCAATATTCTGATGA | LC-B7 | |

| TB9Cs3C3 | CTCTATGATGTTAAAAGAAGTTTTGTAGTAGGGTAAAATCTGACATCCGACCATGAAGGTACGAATTTAATGTGCTTTCATGTGCTTCTGCTATTGTGGTTGCACAGAGGCGCTATGTCTGAGAA | ||

| TB9Cs4C1 | GATCGTGATGATATTAACCCTGCTCCGCTACTGAGTGTTGAAGCATGAAACGATATCCTTCAGGGCTACTGATGC | LC-B3 | |

| TB9Cs4C2 | CCACATGATGATCCATGTATTCACCATATCGACACTGAGTCGGAAACTCCCCGTGACGCACAAGTGATTGTGCATGGAACCGCCCGCACACGCTGTAGGGCACTGACTA | LC-B4 | |

| TB9Cs4C3 | TACTATGATTACATCCATAATGCGTCAGGACACACGAGTGTGTACGTGACTGTTGGATTCTAACGCGACGCCGTAAGCAATATGATCA | ||

| TB9Cs5C1 | GCGAGTGATGAGAACATGGAACTATTGCACGTTTATATGATAAGGCAACTTGATGACTTACACACGCTTCACTAAATATCGTACGAGCGATTACTGATCA | ||

| TB9Cs5C2 | GCATGATGACGAAACAATTTTGCACGTCAGTTTGAATTAGCAAATGTGAAGATGAAATTGACACAGCTATTTTATGGGCTGTCCTGATCT | SnR72 | |

| TB10Cs1C1 | GTGTATGATGAGAAACCTATTTTTATGTAACTCGGGAGAACTGAGCATATTACCTGATGAGTAAACAATCAATCGTTAGATAGTAGCACTGATGT | SnR64 | LC-B6 |

| TB10Cs1C3 | TCACGTGATGAGCATTCAATTCACATCGCGACACACCGATGATTCGAATGAGTGAGCTTCGAATGGGATAAATTTAATCGAGAAAGAACAGCTGAGAT | ||

| TB10Cs1C4 | GAGAATGATGAGATTGCCATCATACTATTGGAAGACGAGTCTGAACCCTGATGCATTTTATCATGCGGCACTGACGA | SNR75 | |

| TB10Cs2C1 | TAACATGACGAGTGAGGAGCGCTATATCTTCTTCACCAAGTGCAGAATTAACCGTCTGAGTACTTTATCACTTTGAAGTGAAGCGCAACCTGATTT | ||

| TB10Cs2C2 | CGCTGATGAAGTTGATATGGTCCGTGTTTCAGATCGCTGAATTGACGCACAATAGCATATCTTCTGAGTT | U18 | TBR9 |

| TB10Cs3C1 | CGCGTGATGAGGTGCAGAAGGCATGTCGCCGCTACGGCGGTGGCTCGCGTAGCCGTCTGGCTGTGCGCGTACTGTGAGCTACTGTACTCCATGGGTGAACAATCTCTGATG | TBR2 | |

| TB10Cs3C2 | GCCTGTGAACACAGCAGGTACACATGATGCACACAATTCAATACTCACTCTGAACATCACTTGTCAGGAGGAATGTGATAACATGCACCACCAGCTGATCA | SnR55 | |

| TB10Cs3C3 | GCGCATGATGTGCTCAACTGGAATTACCATCTGAACGCGGGATACCGCAAGTCGATGAATTAATGCTACGTGCATTACCTCCGCTGTTACTCGTATCACTGACAC | SnR77 | |

| TB10Cs3C4 | CGCGTGATGACATACAAAGTTGTTTGCACATTATCCGACACACCGTGAGCGAGTTACAATATTACAAGAACACCATCTGAAT | AtsnoR41 | TBR6 |

| TB10Cs3C5 | CGGTGATTAGCAGTGCGTCTTCCACCTAACGACCCTTGATGATTATGATACGATGCCTGGTCAACAGAACTATACTACACCAAATTTAGTAAATGAGAC | AtsnoR16 | TBR4 |

| TB10Cs4C1 | GTACTTGAAGATGGGGATGATATGAATATGTTCATACGTAAATGAGCGTTTTCTGCCTGCAATGAAGTAGACTGATGC | ||

| TB10Cs4C2 | CTGCGTGATGTGACTGCAGTTGTAGTGCGCACTGACGACCCATCATGAGCGAGAAACCAACTTTGCGTTTACCAATCTATCTGATTC | ||

| TB10Cs4C3 | TGCGACGATGAGAAACTGTCTAACGACAGGCGGACCGACACATCCAATGAGGACTCTTG AATGTGTACAAATGTTGAGCA | ||

| TB10Cs4C4 | GTGTATGAGGACAGAAGTTGTAGTGCGCGACTGAGTGACAACTTAGTGCTGATTGATACCAACGCTTTCAGCGAGAGTGCTGTACTTGACTGACAC | ||

| TB10Cs4C5 | TGTAGAAGTGAGGCTTATGTTGTGCTTTTTGAAAAATATCACTACACTTACCGGAGTGCACTTGTCAGTATCGTTAAAGCTGAGCC | ||

| TB11Cs1C1 | CCGATTAATAATGTATGTGACGCACGGTGTCTAAAATAGGGGTTACCTGCGTGCTCTGCAGTTGGGTTCCTGAACA | ||

| TB11Cs1C2 | CTTATGATGAGAAGACACGTTTACCTGACACCTCTTCTGATTTAACATTGACGAGTAAAAACTGCTAACAGTTATCCCTGTCTGAC | SnR48 SnR38 |

TBR11 |

| TB11Cs1C3 | GTGCGTGATGTTCAACAACCGCAATCACTCCCATACCTCTGATAGTATTGTTTGATTGACACCATTGCGTACTGATGC | ||

| TB11Cs2C1 | TGAATGATGACTGACAAAACATCACAGACTTTGATGACCCCATGAACAAGAAAAATTGTCGCCCCAGACTGATT | U31 | TBR7 |

| TB11Cs2C2 | GAAGTGATTGACACCTAGGCCGATGTAAAGCCGTCGCAGATGGACGTCGATATCTTGTGAAAACAGTACTATTTTATGCCCTGACTGATC | TBR5 | |

| TB11Cs3C1 | GGACGTGATGAAGAAAAATTATTTACTTCTGTTTGGAGAGGGTTCAGGAACACTCTCCATGACGTTACCATAATTAATCCATTCTCTGATCA | ||

| TB11Cs3C2 | TTTTGATGAAAAACCTTTCATGCTGTGTGACGTACTCCCTTATGAGGGCAGGCACAAGCTGCTTGCGGCCTAGTGTCATGCAATTGATTATAGACGGCATTCTGAA | TBR3 | |

| TB11Cs4C1 | TCTAATGATGACAGTCAATAGTTTCCTGTCAGCCTGACGGCAGTAGAGCCATTTTGAAGACATAATTTTTAACTCAGCTACACTGAATC | SnR71/AtsnoR18 | LC-G2 |

| TB11Cs4C2 | GCCACTGATGCTGTGATGCATAATTGTTGTTCGAGGTCCAAACAGTTTGAGCGATGCATTGATAACGGAACATCAAAAATCACCTTTCGGCTGAGCA | SnR39 | LC-TS1 |

| TB11Cs4C3 | CAGTGTGATGGAAACAACGATTATGTGTACGTGAAGGTCAATATGCCTTACTTTATGAGCGCGCTTATTGAATACTAAATCAAACTCAACAGGTCTGACTG | AtsnoR53 | LC-TS2 |

The sequences of the C/D snoRNAs were obtained from the T. brucei genome database (http://www.genedb.org/genedb/tryp/blast.jsp). Potential C/D- and C′/D′-boxes are shown in bold letters. The coding region is predicted based on the position of the C/D-boxes. In cases where the ends of the molecule were not experimentally determined, we provide 5 nt upstream from the C-box and 3 nt downstream from the D-box. The sequences predicted to interact by base-pairing with their targets are underlined. Homolog names in other organisms and other trypanosomatid species as well as previous names are provided.

Although most snoRNA clusters are repeated in the genome and usually carry both C/D and H/ACA RNAs, several clusters are single-copy genes (clusters 5, 13, and 20). In addition, we identified clusters that carry single C/D RNAs (clusters 1 and 3). To determine whether snoRNAs present in a single-copy gene and snoRNAs within a cluster that carries only a single snoRNA are expressed, we examined the expression of the RNA by primer extension. The results (Fig. 2B ▶) show that the snoRNAs TB3Cs2C1, TB6Cs2C1, and TB9Cs5C2 are, indeed, expressed, suggesting also the expression of a cluster (2, 5, and 13). Of special interest is the expression of TB3Cs2C1 (which is repeated many times in the same cluster). The sequence of these copies differs slightly, and although the 3′ half of the molecule is conserved, the 5′ half differs; a 3-nt deletion exists in copies 1A and 1B (illustrated in Fig. 2A ▶). However, both types of genes are expressed, since two extension products were observed that differ in 3 nt. The level of these transcripts is in accordance with the ratio between the copies containing or lacking the 3-nt deletion (Fig. 2C ▶). Interestingly, we could not detect the expression of cluster 1, suggesting that this cluster is either not expressed or only poorly expressed.

The distance between the different snoRNA genes (intergenic region) ranges from 15 to 450 nt. We have previously demonstrated that although the intergenic region can vary, 10 nt is essential for proper processing of the snoRNA (Xu et al. 2001; Liang et al. 2004). Interestingly, as shown in Figure2A ▶, we detected efficient processing of the snoRNA TB10Cs3H1 (cluster 16) that is spaced by only 15 nt from the upstream RNA.

The repertoire and properties of the T. brucei C/D and H/ACA-like snoRNAs

The repertoire of the 57 C/D snoRNAs identified in these clusters is presented in Table 1 ▶. All the C/D snoRNAs range in size from 67 to 118 nt. Of the 57 C/D snoRNAs, 27 have the potential to guide two modification sites. In 14 out of the 27 snoRNAs, the sites lie adjacent to each other on the target RNA. In the other cases, the two sites are either located on the same RNA or even on two different RNA molecules. We were able to identify the targets guided by 56 out of 57 C/D snoRNAs. In addition, 39 of the T. brucei C/D snoRNAs have homologs in other organisms such as yeast (these snoRNAs are designated as SnX), human (designated as Ux) or Arabidopsis (designated as AtsnoX). The fact that we identified homologs to the T. brucei RNA in other eukaryotes suggests that all these snoRNAs should be expressed in trypanosomes as well. Interestingly, 27 snoRNAs seem to be trypanosome-species specific (cf. the two columns in Table 1 ▶). Out of these, six snoRNAs were shown to be expressed in T. brucei (Dunbar et al. 2000b), and four were shown to be expressed in L. collosoma (Xu et al. 2001; Liang et al. 2004).

The analysis presented here suggests that at least 38 of the C/D snoRNAs are expressed, but since the rest are situated in expressed clusters, it is reasonable to assume that all these snoRNAs are expressed.

The size of the C/D snoRNAs and their 5′ and 3′ ends were deduced based on experimental mapping data of several of these snoRNAs. The mapping data indicate that the 5′ end of the molecule is situated 1–5 nt upstream from the C-box. In those cases where the 5′ end was experimentally mapped, we indicated the exact location. For the remaining molecules, we provided the sequence of the 5 nt upstream from the C-box. Based on experimental data, the 3′ end of the C/D molecule is found 1–3 nt downstream from the D-box. For those RNAs with no available experimental data, we provided the sequence of the 3 nt downstream from the D-box. Interestingly, unlike most of the eukaryotic C/D snoRNAs, as well as those described in L. collosoma (Xu et al. 2001; Liang et al. 2004), the 3′ and 5′ ends of T. brucei snoRNA cannot form a perfect stem. Note that the comparative analysis between T. brucei and T. cruzi cannot be helpful in determining the ends of the molecule, since the sequence of the C/D snoRNA is not conserved outside the domain that is complementary to the target site (see Fig. 4 ▶).

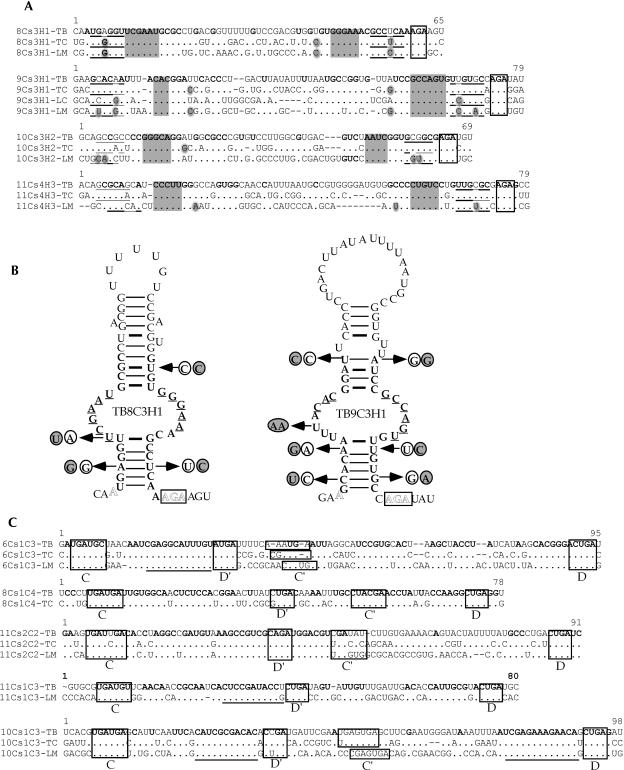

FIGURE 4.

Sequence alignment of snoRNAs from different trypanosomatid species. (A) Examples of H/ACA RNAs. The AGA motif is boxed. The gaps are shown as short lines, whereas conserved residues are given in dots. The nucleotides conserved in all species are in bold. The species designations are (TB) Trypanosoma brucei, (TC) Trypanosoma cruzi, and (LM) Leishmania major. Domains involved in base-pairing with their targets are shadowed. (B) Secondary structure of H/ACA-like RNA, TB8Cs3H1, and TB9Cs3H1. The sequences of the RNA are from T. brucei. Compensatory changes between these sequences among the trypanosomatid species are marked by arrows. The sequences of T. cruzi are circled, and the L. major sequences are circled and shadowed. (C) Examples of C/D snoRNAs. The C/D- and C′/D′ boxes are indicated. The sequences involved in base-pairing with target RNAs are underlined.

All the H/ACA-like RNAs identified in this study (34) are summarized in Table 2 ▶. The H/ACA RNAs are smaller in size than the C/D snoRNA, ranging from 57 to 78 nt. Determination of the H/ACA-like molecular termini was based on experimental data provided for several of these molecules including SLA1 (Roberts et al. 1998), h1 (Liang et al. 2001), and h2 and h3 (Liang et al. 2004). In all H/ACA snoRNAs known so far, the terminal box ACA is located 3 nt upstream from the 3′ end. Interestingly, in all the T. brucei homologs, we only detected AGA-boxes and not ACA or other possibilities, such as AAA, which was previously identified in guide RNAs in other eukaryotes (Ganot et al. 1997; Ni et al. 1997). All the H/ACA-like molecules can form only a single stem–loop structure. Upon inspecting all the mapping data that we have on these RNAs in trypanosomatid species (Liang et al. 2001, 2002, 2004), we have found that the 5′ end of these molecules is usually situated 1–3 nt upstream from the stem structure. The sequences given in Table 2 ▶ include 3 nt upstream from the stem except for cases in which the 5′ end was experimentally determined.

TABLE 2.

The T. brucei H/ACA-like RNAs

| Name | Sequence | Homolog | Previous name or trypanosome homolog |

| TB6Cs1H1 | GGCTAGCGAAAACACAGGCGTTTTGCTTACGTCAATCACTGCGTCTGCACCTGTGCTACC CGAGAGTT | ||

| TB6Cs1H2 | CGAGCCCCGTGGGTGAGGCGGCGGCGGTAACTCTTTGGTGCTGTGACGGCCTCAATCG GACCCGCGAGAGCT | LC-H4 | |

| TB6Cs1H3 | GTACCGCGGGTTGCACCGTTGCGGGACACGCTGATTGTCCATGTGACGGACTTGCCTGT GGAAGAGTG | ACA24 | |

| TB6Cs1H4 | ACACCTCATTATTAAAGGTCCCTTGGCGACTGTACTTATCGATGCCGCTCCACAGGATACC CATTGAGGTTAGATGC | ||

| TB6Cs2H1 | GAAACACAGAAATCGTGATCCCTATTGATACACGTTTTTCAGCTGCGGATTATCAAAACTG TGTGAGATGA | ||

| TB8Cs2H1 | ACACCTCCGCTTCGCTCGTGGCATTCTTCCAGTGAGCGCACTTACGATGGATGGTGGAGG AAGAATA | ||

| TB8Cs3H1 | CAATGAGGTTCGAATGCGCCTGACGGTTTTTGTCCGACGTGGTGTGGGAAACGCCTCAAA GAAGT | LC-H3 | |

| TB9Cs1H1 | ACAGCACAGAAAATGAAGCTAGTTATGGCGTACCGCTGCTGCTCTAGTGCCGACACTGTG CGAGATGC | SnR34 | LC-H1 |

| TB9Cs1H2 | ACACGGGGCAATCCGAGGTCAGTGAGCTTCACTTCGTGCCGCATGATGCCTTCTGGTGG CTCCGGAGAAGC | LC-H9 | |

| TB9Cs1H3 | AGAACGCGCTATTAGCTCCCAACGGGTATGACTGCTTCCACTTGGGTTCCTGAGGCGTGT GAGAGTG | LC-H8 | |

| TB9Cs2H1 | AAGGCCCACATTGGAGTTGTGTCTTGGGCTAACATTTCTGTGTCCTTGTTTGCACACTCAC GTGGTCCGAGAATT | ||

| TB9Cs2H2 | AAAGGGGCTTTAGCCATGGAGCGGCCGTTTTGTGATTGCATGCCGTAGGCCATCTTGGTG CGCTCCGAGAGTT | ACA10 | |

| TB9Cs3H1 | GAAGCACAATTTACACGGATTCACCCTGACTTATATTTTAATGCCGGTGTTATCCGCCAGT GTTGTGCCAGATAT | SnR34 | LC-H5 |

| TB9Cs3H2 | CGAGTGCCCTCAGGTATTGTGGTGTTTGTTGCTTATCGCCATCACAGGTTCAAGAGGCAC AAGAAGT | Atsnor77 | |

| TB9Cs4H1 | TAAGGTTGCCTGTGTACCTCATGCGTCTCTTTGTGGTGTTGTGGGGAATGAAGGCGACCG AGATAC | ||

| TB9Cs4H2 | GTAGGCCCGCCAGCTACCACGTGGAGTGTATACTCTCTATCTCTACGACGGTCGTTCTACC GGGCCAAGAAAC | SnR37 | |

| TB9Cs4H3 | TAAGTTTATTATTATCATTGTTTCAAGAAAGACAAAACTATCCGTAAACGAGAAAA | ||

| TB10Cs1H1 | TCATCCCCTTTAATAGCGAGTGGTCTTTGTGTGCATCTCCGCAAACCACTCGTCTACACCG GGGGAAAGATAA | ||

| TB10Cs1H2 | CGAGCACTCATTTCAAGCTGCGCGAGCATAAGCGTGTTGCTCCGTGGTCGGGTGACGTG CGAGACAC | ||

| TB10Cs1H3 | GCAGGAACGTGGCAGGCTACCGAGGTCACACTCGTGCTTCGCGTGGTTCAACAACATGG TCCCAGATTG | ||

| TB10Cs2H1 | TACGGCGTTGTCGGTTGGGCCAGTGGCAAATTTTATCCCTGCAGCCCTATCTCGCAACTC CTAGAACC | Atsnor93 | |

| TB10Cs2H2 | TCAGGGAGTTCTGTACGCCGCTGAGTGGTATTGCTCGCTTAGTGGAGCGATTTACTCCCC AGATTT | ||

| TB10Cs3H1 | AGCAGTGTCGCTATGCGTTCCCGTCAGTAATACGGGCTAACGGTACGAAGCACGTGCGA GAGGT | ACA10 | |

| TB10Cs3H2 | GCAGCCGCCCCGGGCAGGATGGCGCCCGTGTCCTTGGCGTGACGTCTAATCGGTGCGG CGAGATGT | SnR32 | |

| TB10Cs4H1 | TTATTTCTTTTCATATGTACAAACCTAAGGCAGTACCAAAATACGCTTATCACTCATCACCCA AGAAAAATAGACAG | ||

| TB10Cs4H2 | TTACCGTCTCTGTCTAACGCCTCACATGTGCAGAAATCGTTGTGGGGCGATTCAGGAGGC GGAGATAT | ||

| TB10Cs4H3 | CGACGCCCATACAACCGCCCCACACCGTGCTTTGCATGCATTGTGGGGTGATACATGTGG CGGAGATGT | ||

| TB10Cs4H4 | TGAGGAGGCCCGTAGCCACGGCATGCCTTTTTGGTGGTGCGTTGTGGGTGGTGGCTTTC CAAGAGGC | ||

| TB11Cs2H1 | AAAGCTCTTTTATGTAGTGTGCGTACCACGAAAGTAGCAGGTACTGCACACGAAACTGGA GAGCGAGACTC | SLA1 | |

| TB11Cs3H1 | AAAGCCCTCATGAACAATCCCACCGGTGAGTGTACTCATTTAATCTCGTGCGTGGACCTAG GAGCGCCAAGATTT | ||

| TB11Cs3H2 | TCGTTGTACCGAATGTGGCGTGAGCGTTGTGCATACCGGCGTATTCGCAATGCCGCCCTA AACGTACAAAGATTG | ||

| TB11Cs4H1 | AAATCTTACCCTGTCTAGCTGCCTGTCAGTATACTTTCGGTGACGGTATTGGCTCGAAAGT GTAAGAGAGATCG | ||

| TB11Cs4H2 | AGAGGTATGCATTGAGACCCACTGCCTTCATATGTAGGCGAGTGGGAGCATCAGCATCCC GAGATAA | LC-H7 | |

| TB11Cs4H3 | ACAGCGCAGCATCCCTTGGGCCAGTGGCAACCATTTAATGCCGTGGGGATGTGGCCCCT GTCCTGTTGCGCGAGAGCC | LC-H6 |

The sequences (±3 nt in 5′-end) were obtained from the T. brucei genome database. The coding region is predicted based on the position of the AGA-box and the secondary structure. The AGA-box and the “A” 1 nt upstream from the stem are shown in bold letters. Homolog names in other organisms are given.

Interestingly, we also found that the first nucleotide present upstream from the stem is almost always an A. We are currently investigating the significance of this conserved nucleotide for processing and/or nucleolar localization. Finding the target of H/ACA-like RNA is more difficult than that of the C/D snoRNA. However, we were able to identify the potential targets of all the molecules presented in this study except one. With H/ACA-like RNA, nine out of 34 T. brucei molecules have homologs in other eukaryotes. Nine additional molecules are trypanosome-specific; one RNA is the SLA1 that is a special H/ACA-like RNA (Liang et al. 2002); four were experimentally studied in L. collosoma (Liang et al. 2001, 2004); and the expression of four H/ACA-like RNAs in T. brucei were verified experimentally in this study (see Fig. 2A ▶).

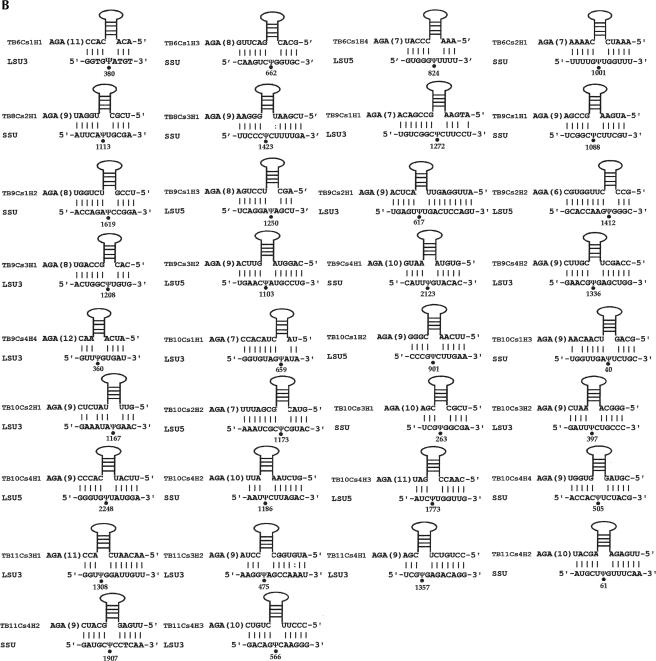

The potential targets for C/D and H/ACA-like RNAs

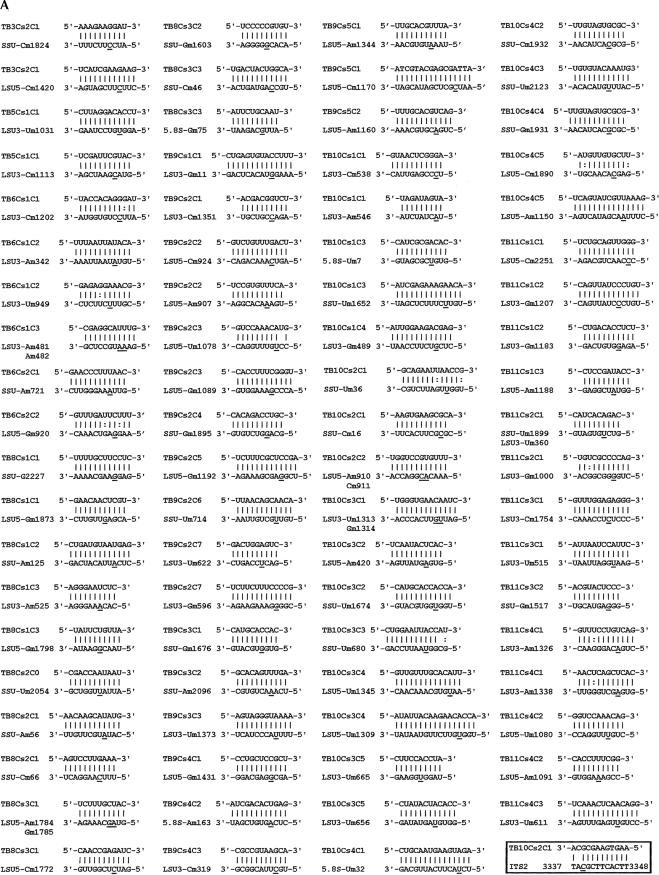

The base-pair interactions between the guide RNAs and their targets are presented in Figure3 ▶ (Fig. 3A ▶ for C/D and Fig. 3B ▶ for H/ACA-like RNAs). The interaction domain between the C/D RNA and its target is relatively easy to find, since there is perfect complementarity of 10–16 nt between the C/D snoRNA and its target site. As suggested previously (Levitan et al. 1998; Dunbar et al. 2000b; Xu et al. 2001), the +5 rule for guiding modifications applies to all C/D RNAs identified in this study. This is in contrast to the guiding rules suggested for the C/D RNAs present in the SLA1 locus (cluster 19) (Roberts et al. 1998). Interestingly, TB10Cs2C1 also has the potential to base-pair (10 bp) with the ITS2 (internal-transcribed spacer) region of the rRNA precursor, as shown in Figure3A ▶ (boxed). SnoRNA interactions with pre-rRNA are relatively rare. However, U8 snoRNA has been shown in vertebrates to be essential in ITS2 processing, and it base-pairs with the precursor serving as a chaperone but has no guide methylation function (Peculis 1997; Michot et al. 1999). It remains to be seen if TB10Cs2C1 guides modification on pre-rRNA. Only for one of the C/Ds (TB11Cs2C2), the target on either rRNA or snRNAs could not be identified. However, this RNA is in the SLA1 locus that encodes for RNAs with special functions. It is therefore possible that this RNA may either function in RNA processing or direct modification on a novel target.

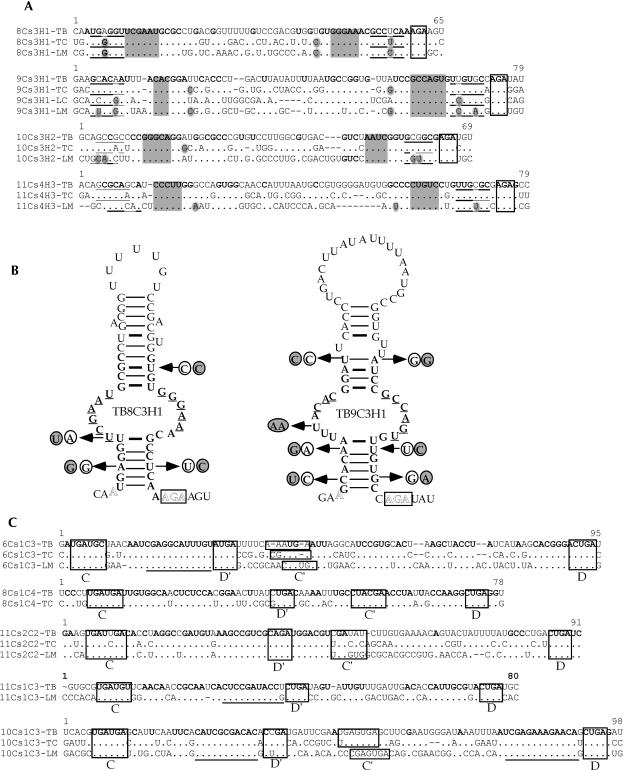

FIGURE 3.

Potential base-pair interaction between the snoRNAs and their targets. (A) C/D snoRNAs and their target sites. The name of the snoRNA, the region of complementarity, and the nucleotide to be modified on rRNAs are given. (SSU) Ribosomal RNA small subunit; (LSU 5′/3′) ribosomal RNA large subunit, 5′ and 3′ half, respectively; (5.8S) 5.8S ribosomal RNA. Nm designates 2′-O-methylation. (B) H/ACA RNAs and their targets. The designation of rRNA is as described in A. The target sites are indicated by dots and the positions are given. The lengths (in nucleotides) between the interaction domain and the AGA-box are indicated in brackets.

As shown in Figure3B ▶, we have identified all the potential H/ACA targets except for one. In all cases, the base-pair interaction in the pseudouridylation pocket consists of 3–8 nt, which are disrupted by the pseudouridine on the target RNA. This relatively short duplex makes it harder to identify the targets guided by these RNAs.

Sequence and structure conservation among T. brucei, T. cruzi, and L. major

To examine whether the conservation of the C/D and H/ACA among the trypanosomatid species can be helpful in identifying features common to the trypanosome snoRNA, which may assist in finding the snoRNAs that we have not yet identified (see Discussion), we examined the conservation of C/D and H/ACA RNAs in three trypanosomatid species: T. brucei, T. cruzi, and L. major. An example of such a comparison is presented in Figure4A ▶, indicating that the H/ACA-like RNAs are slightly more conserved (58%–75% identity) at the primary sequence level compared with C/D RNAs (43%–75% identity). In other examples, we noticed that on the primary sequence level, the C/D snoRNAs are more conserved than the H/ACA-like RNAs because of the conservation in the boxes and in the extensive interaction domains. Note that the percentage of identity among C/D homolog molecules depends on the length of the molecule. In cases in which the molecule is short and the two extensive complementary sequences to the target exist, the overall identity is high, yet the region between the conserved domains can be highly divergent.

The C- and D-boxes are highly conserved, but deviations can be found in the C′ and D′ boxes. In all C/D snoRNAs, the homologous guide RNAs in the three or four trypanosomatid species have the potential to guide the same targets either at adjacent sites or on two different RNA molecules. For example, TB3Cs2C1 has two targets: one on SSU and one on LSU. An inspection of the conservation and compensatory changes in the two H/ACA RNAs (TB8Cs3H1 and TB9Cs3H1) reveals the conservation and several structural features of the trypanosome H/ACA-like RNAs (see Fig. 4B ▶).

The H/ACA-like RNAs show a high degree of conservation at their secondary structure. The conserved domains are as follows: the lower stem consists of at least 6 bp; the pseudouridylation pocket can range from 5 to 10 nt; and the upper stem usually contains four conserved base pairs. These features can be clearly seen in Figure4B ▶. The structure of the stems is essential for the functioning of these molecules, since compensatory changes in these domains exist in T. brucei, T. cruzi, and L. major RNAs. There is a great variation in the length of the upper stem, both in the degree of complementarity (number of bulges) and also in the size of the terminal loop. Mutation analysis in L. collosoma is currently in progress to determine the structural features essential for RNA processing, RNP biogenesis, and nucleoli localization of these RNAs.

The localization of modifications guided by the C/D and H/ACA-like RNAs on the rRNA secondary structure

Next, we were interested in mapping the potential modifications guided by both C/D and H/ACA RNAs, and in comparing the pattern of modifications on the rRNAs of trypanosomes to those described in humans, yeast, and plants. The results are summarized in Table 3 ▶ and specify the homologs to trypanosome C/D snoRNAs from yeast, humans, and plants including their potential target sites on different RNAs (LSU, 5′ half and 3′ half, SSU or 5.8 rRNA). The results indicate that we identified 84 potential 2′-O-methylations on the rRNA in T. brucei. Among those, 44 predicted sites were found to be modified in at least another organism. Of these modifications, 23 are shared between plants, humans, yeast, and trypanosomes and therefore represent the most highly conserved modifications. Six modifications seem to be unique only to plants and trypanosomes: three to trypanosomes, humans, and plants; four to plants, yeast, and trypanosomes; and four common to trypanosomes and yeast. A great overlap exists between plants and trypanosomes. The most striking finding was the number of species-specific modifications identified in trypanosomes.

TABLE 3.

The predicted modifications on T. brucei rRNA compared to plants, humans, and yeast

| T. brucei | Plant | Human | Yeast | ||||||

| Site | SnoRNA | snoRNA | Site | snoRNA | Site | snoRNA | Site | Conservation of sites | |

| SSU | Cm16 | TB10Cs2C1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Um36 | TB10Cs2C1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Cm46 | TB8Cs3C3 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Am56 | TB8Cs2C1 | AtU27 | Am28 | U27 | Am27 | SnR74 | Am28 | PHYT |

| SSU | Cm66 | TB8Cs2C1 | AtsnoR66 | Cm38 | PT | ||||

| SSU | Am125 | TB8Cs1C2 | Am98 | SnR51 | Am100 | YHT | |||

| SSU | Um680 | TB10Cs3C3 | AtsnoR77Y | Um580 | Nd | Um627 | SnR77 | Um578 | PHYT |

| SSU | Um714 | TB9Cs2C6 | AtsnoR13 | Um613 | PT | ||||

| SSU | Am721 | TB6Cs2C1 | AtU36 | Am621 | U36a | Am668 | SnR47 | Am619 | PHYT |

| SSU | Gm1517 | TB11Cs3C2 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Gm1603 | TB8Cs3C2 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Um1652 | TB10Cs1C3 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Um1674 | TB10Cs3C2 | U33 | Um1270 | U33 | Um1326 | SnR55 | Um1267 | PHYT |

| SSU | Gm1676 | TB9Cs3C1 | AtsnoR21 | Gm1272 | U32 | Gm1328 | SnR40 | Gm1269 | PHYT |

| SSU | Cm1824 | TB3Cs2C1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Gm1895 | TB9Cs2C4 | AtsnoR19 | Gm1431 | U25 | Gm1490 | SnR56 | Gm1427 | PHYT |

| SSU | Um1899 | TB11Cs2C1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Gm1931 | TB10Cs4C4 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Cm1932 | TB10Cs4C2 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Um2054 | TB8Cs2C0 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Am2096 | TB9Cs3C2 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Um2123 | TB10Cs4C3 | AtU43 | Cm1641 | U43 | Cm1705 | SnR70 | Cm1638 | PHYT |

| SSU | Gm2227 | TB8Cs1C1 | AtsnoR23 | Am1754 | Nd | Am1850 | Nd | Am1779 | PHYT |

| 5.8s | Um7 | TB10Cs1C3 | T | ||||||

| 5.8s | Um32 | TB10Cs4C1 | T | ||||||

| 5.8s | Gm75 | TB8Cs3C3 | AtsnoR39BY | Gm79 | Nd | Gm75 | PHT | ||

| 5.8s | Am163 | TB9Cs4C2 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Am420 | TB10Cs3C2 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Am907 | TB9Cs2C2 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Am910 | TB10Cs2C2 | AtU18 | Am660 | U18 | Am1313 | U18 | Am647 | PHYT |

| LSU5 | Cm911 | TB10Cs2C2 | U18 | Cm648A | YT | ||||

| LSU5 | Gm920 | TB6Cs2C2 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Cm924 | TB9Cs2C2 | AtsnoR58Y | Cm674 | Nd | Cm1327 | SnR58 | Cm661 | PHYT |

| LSU5 | Um1078 | TB9Cs2C3 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Um1080 | TB11Cs4C2 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Gm1089 | TB9Cs2C3 | AtsnoR39BY | Gm812 | Nd | Gm1509 | SnR39B | Gm803 | PHYT |

| LSU5 | Am1091 | TB11Cs4C2 | AtU51 | Am814 | U51/U32a | Am1511 | SnR39/59 | Am805 | PHYT |

| LSU5 | Am1150 | TB10Cs4C5 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Am1160 | TB9Cs5C2 | AtsnoR72Y | Am883 | SnR72 | Am874 | PYT | ||

| LSU5 | Cm1170 | TB9Cs5C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Am1188 | TB11Cs1C3 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Gm1192 | TB9Cs2C5 | AtU80 | Um915 | U80 | Gm1612 | SnR60 | Gm906 | PHYT |

| LSU5 | Um1309 | TB10Cs3C4 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Am1344 | TB9Cs5C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Um1345 | TB10Cs3C4 | AtsnoR41Y | Um1064 | PT | ||||

| LSU5 | Cm1420 | TB3Cs2C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Gm1431 | TB9Cs4C1 | AtU38 | Am1140 | U38ab | Am1858 | SnR61 | Am1131 | PHYT |

| LSU5 | Cm1772 | TB8Cs3C1 | AtU24 | Cm1439 | U24 | Cm2338 | U24 | Cm1435 | PHYT |

| LSU5 | Am1784 | TB8Cs3C1 | AtU24 | Am1451 | U76 | Am2350 | U24 | Am1447 | PHYT |

| LSU5 | Gm1785 | TB8Cs3C1 | Gm2351 | U24 | Gm1448 | TYH | |||

| LSU5 | Gm1798 | TB8Cs1C3 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | G1873 | TB8Cs1C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Cm1890 | TB10Cs4C5 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Cm2251 | TB11Cs1C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Gm11 | TB9Cs1C1 | AtU34 | Um1882 | U34 | Um2824 | SnR62 | Um1886 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Gm319 | TB9Cs4C3 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Am342 | TB6Cs1C2 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Um360 | TB11Cs2C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Am481 | TB6Cs1C3 | SnR13 | Am2278 | YT | ||||

| LSU3 | Am482 | TB6Cs1C3 | AtU15 | Am2271 | U15 | Am3764 | SnR13 | Am2279 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Gm489 | TB10Cs1C4 | AtU15 | Gm2278 | SnR75 | Gm2286 | PYT | ||

| LSU3 | Um515 | TB11Cs3C1 | Um3787 | HT | |||||

| LSU3 | Am525 | TB8Cs1C3 | AtsnoR44 | Am2316 | U79 | Am3809 | PHT | ||

| LSU3 | Cm538 | TB10Cs1C1 | AtsnoR44 | Cm2327 | U74 | Cm3820 | SnR64 | Cm2235 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Am546 | TB10Cs1C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Gm596 | TB9Cs2C7 | SnR190 | Gm2394 | YT | ||||

| LSU3 | Um611 | TB11Cs4C3 | AtsnoR53 | Um2400 | PT | ||||

| LSU3 | Um622 | TB9Cs2C7 | AtsnoR37 | Um2411 | U52 | Um3904 | SnR78 | Um2414 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Um656 | TB10Cs3C5 | AtsnoR16.1 | Um2445 | PT | ||||

| LSU3 | Um665 | TB10Cs3C5 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Um949 | TB6Cs1C2 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Gm1000 | TB11Cs2C1 | AtU31 | Gm2610 | U31 | Gm4166 | SnR67 | Gm2616 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Um1031 | TB5Cs1C1 | AtsnoR10 | Um2641 | Nd | Um4197 | PHT | ||

| LSU3 | Cm1113 | TB5Cs1C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Gm1183 | TB11Cs1C2 | AtsnoR1 | Gm2781 | SnR48 | Gm2788 | PYT | ||

| LSU3 | Cm1202 | TB6Cs1C1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Gm1207 | TB11Cs1C2 | AtsnoR38Y | Gm2805 | SnR38 | Gm2812 | PYT | ||

| LSU3 | Um1313 | TB10Cs3C1 | snR52 | Um2918 | YT | ||||

| LSU3 | Gm1314 | TB10Cs3C1 | Gm4459 | snR52 | Gm2919 | TYH | |||

| LSU3 | Am1326 | TB11Cs4C1 | AtsnoR18 | Am2924 | PT | ||||

| LSU3 | Am1338 | TB11Cs4C1 | AtU29 | Am2936 | U29 | Am4493 | SnR71 | Am2943 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Cm1351 | TB9Cs2C1 | AtU35 | Cm2949 | U35 | Cm4506 | SnR73 | Cm2956 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Um1373 | TB9Cs3C3 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Cm1754 | TB11Cs3C1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ40 | TB10Cs1H3 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ61 | TB11Cs4H2 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ263 | TB10Cs3H1 | ACA10 | Ψ 214 | HT | ||||

| SSU | Ψ505 | TB10Cs4H4 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ662 | TB6Cs1H3 | ACA24 | Ψ 613 | HT | ||||

| SSU | Ψ1001 | TB6Cs2C1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ1088 | TB9Cs1H1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ1113 | TB8Cs2H1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ1186 | TB10Cs4H2 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ1423 | TB8Cs3H1 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ1619 | TB9Cs1H2 | T | ||||||

| SSU | Ψ2123 | TB9Cs4H1 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Ψ824 | TB6Cs1H4 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Ψ901 | TB10Cs1H2 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Ψ1103 | TB9Cs3H2 | AtsnoR77 | 826 | Nd | 1523 | PHT | ||

| LSU5 | Ψ1250 | TB9Cs1H3 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Ψ1412 | TB9Cs2H2 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Ψ1773 | TB10Cs4H3 | T | ||||||

| LSU5 | Ψ2248 | TB10Cs4H1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Ψ360 | TB9Cs4H4 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Ψ380 | TB6Cs1H1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Ψ397 | TB10Cs3H2 | SnR32 | 2191 | YT | ||||

| LSU3 | Ψ475 | TB11Cs3H2 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Ψ566 | TB11Cs4H3 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Ψ617 | TB9Cs2H1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Ψ659 | TB10Cs1H1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Ψ1167 | TB10Cs2H1 | AtsnoR93 | 2773 | Nd | 4330 | PHT | ||

| LSU3 | Ψ1208 | TB9Cs3H1 | AtU65 | 2816 | U65 | 4373 | SnR34 | 2823 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Ψ1272 | TB9Cs1H1 | AtU65 | 2870 | U65 | 4427 | SnR34 | 2877 | PHYT |

| LSU3 | Ψ1308 | TB11Cs3H1 | T | ||||||

| LSU3 | Ψ1336 | TB9Cs2H2 | ACA10 | Ψ 4492 | SnR37 | 2941 | HTY | ||

| LSU3 | Ψ1357 | TB11Cs4H1 | T |

The predicted modifications in T. brucei (T) are compared with their counterparts in S. cerevisae (Y), plants (Arabidopsis) (P), and humans (H). The target site on the respective rRNA is given. Nm and Ψ designate 2′-O-methylation and pseudouridine, respectively. The modifications shared by other species are indicated. There are collectively 84 Nms; 44 sites are conserved with at least one other organism; 36 are conserved between trypanosomes and plants; 34 between trypanosomes and yeast; and 30 between trypanosomes and humans. Among the 32 predicted pseudouridines, only nine are conserved.

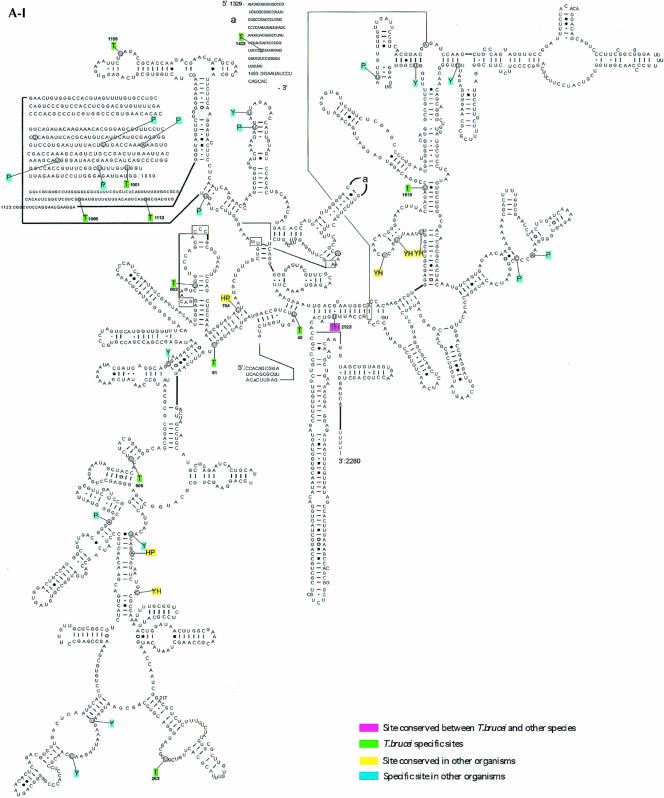

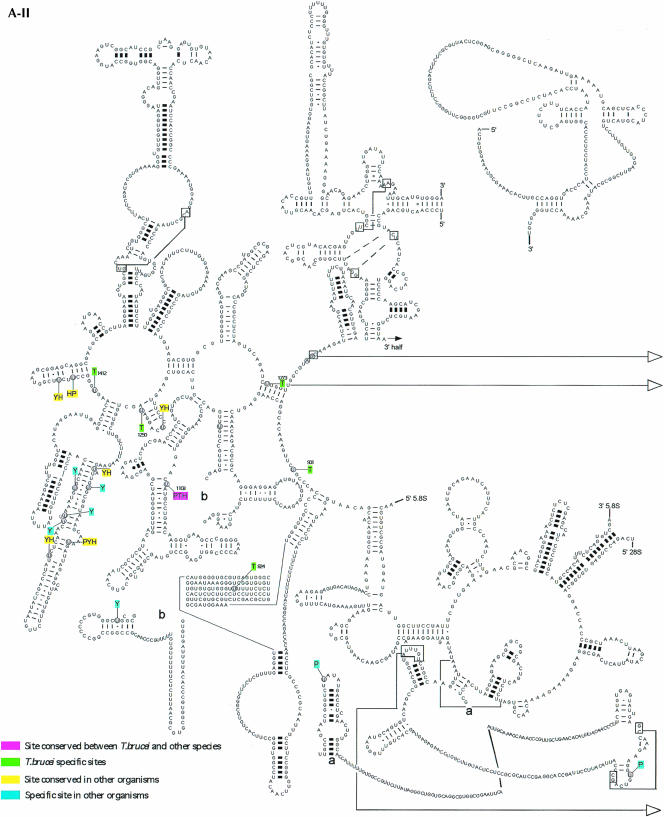

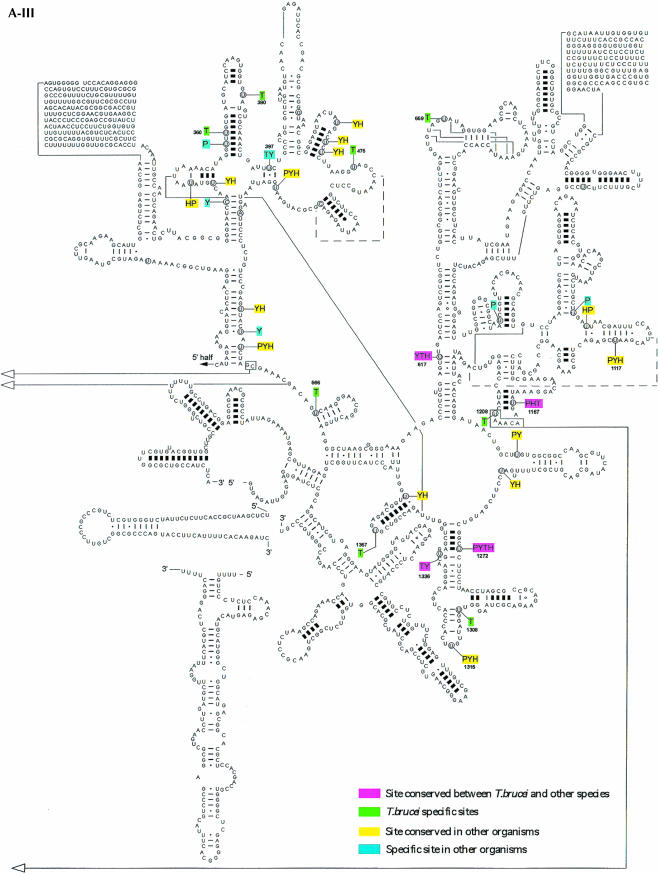

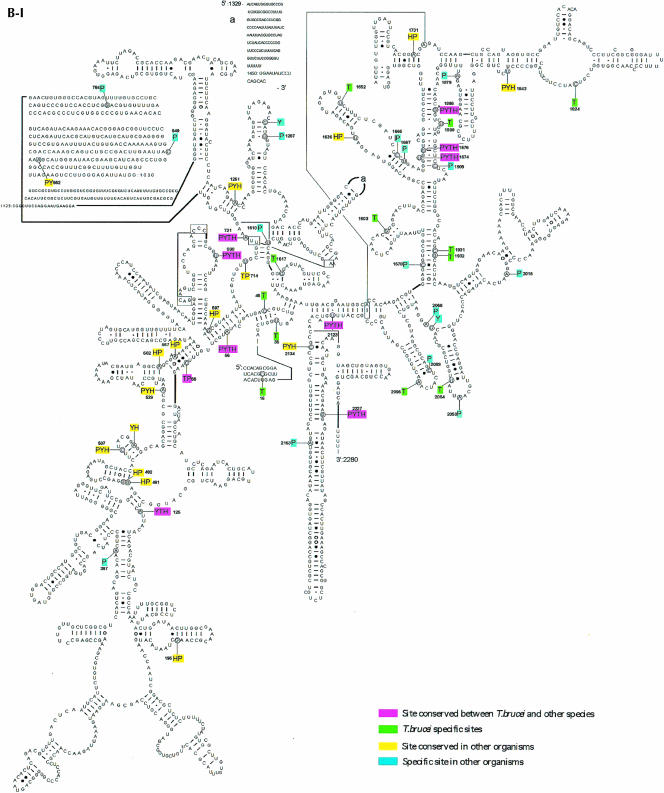

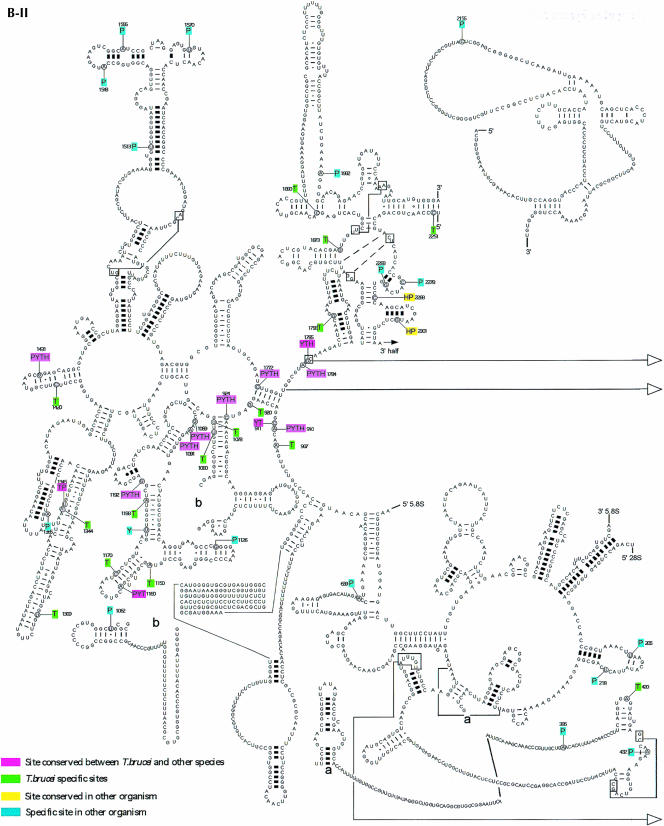

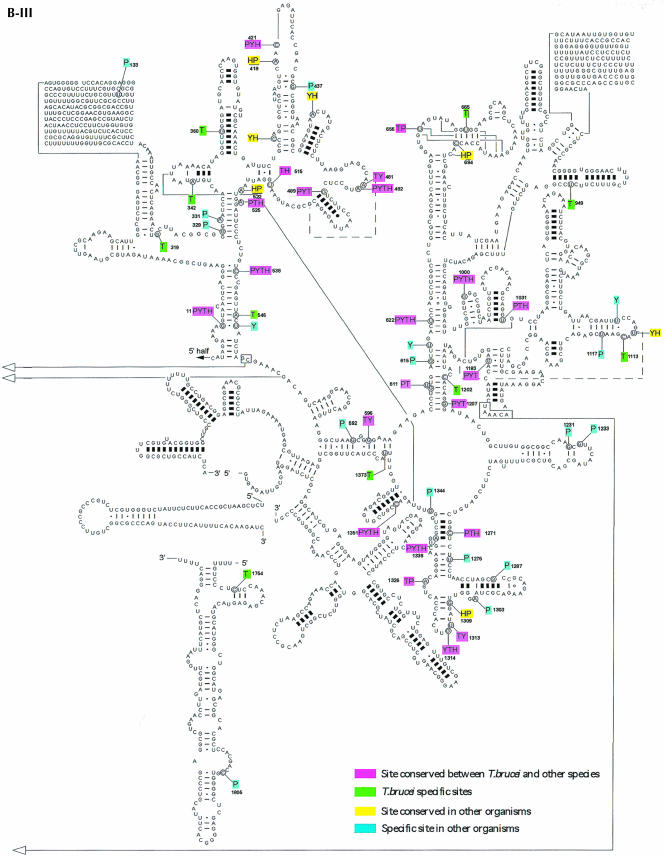

In the case of the H/ACA-like RNAs, 32 pseudouridines were predicted. This analysis may suffer from a lack of knowledge about these RNAs in other organisms. As already mentioned, identification of H/ACA RNA is not trivial. Only recently was a program developed that is able to identify the H/ACA-like RNA on a genome scale (Edvardsson et al. 2003). From the data currently available in the literature, we were able to identify homologs for eight out of the 34 RNAs. Among those, two were found in all the organisms mentioned above and represent modifications on highly conserved positions (Maden et al. 1995; Ofengand and Bakin 1997; Samarsky and Fournier 1999; Brown et al. 2003b). The rest of the molecules seem at this point to guide species-specific modifications. It was of interest to map these predicted modifications on the secondary structure of rRNA and to compare them to modifications that were mapped or predicted in other organisms (yeast, humans, plants). The results are presented in Figure5 ▶. The pseudouridines on the secondary structure of the large rRNA subunits 5′ and 3′ and the small subunits are presented in Figure5A ▶, and the 2′-O-methylations on these RNA molecules are in Figure5B ▶. Trypanosome-species-specific modifications that do not exist in other eukaryotes are in green. Conserved modifications including those found in trypanosomes are in pink, and modifications that exist in more than one organism are given in yellow. Organism-specific modifications (other than trypanosomes) are in light blue. The results indicate that both types of modifications are clustered in functionally important domains. These sites are situated in the A, P, and E sites, the peptidyl transferase active site, the polypeptide exit tunnel, and the intersubunit bridges (Decatur and Fournier 2002). Interestingly, the majority of the trypanosome-species-specific modifications increase the level of modifications in those domains that are already rich in such modifications, but trypanosome-species-specific modifications also lie outside these regions. Many of the trypanosome-species-specific modifications are located close to plant-specific modifications. Surprisingly, the modifications are also rich in the 5′-terminal region of the trypanosome SSU rRNA, whereas in yeast this region lacks modifications.

FIGURE 5.

Localization of modified nucleotides on the secondary structure of rRNA. (A) Pseudouridine on rRNA SSU (A-I), LSU 5′ half (A-II), and 3′ half (A-III). The secondary structure of T. brucei rRNA was predicted based on the structure presented at http://www.icmb.utexas.edu. The modified nucleotides in T. brucei (T), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Y), and plant Arabidopsis (P) are indicated. The sites of humans (H) represent only the most conserved modifications. The designation of colors is indicated in each panel. (B) 2′-O-Methylations on rRNA SSU (B-I), LSU 5′ half (B-II), and 3′ half (B-III). The modified nucleotides in T. brucei (T), S. cerevisiae (Y), and plant Arabidopsis (P) are given. The highly conserved modifications in humans (H) are also shown.

Partial mapping of the 2′-O-methyls and Ψ on rRNA

To verify that the modifications predicted in this study (Fig. 5 ▶; Table 3 ▶) exist on rRNA, we began to map the modifications on the rRNA LSU 5′ and 3′ half (Fig. 6A,B ▶), SSU (Fig. 6C ▶). Mapping was performed by primer extension using different dNTP concentrations. At lower concentrations of dNTPs, the reverse transcriptase pauses 1 nt before the Nm (Kiss-Laszlo et al. 1996). The results indicate that the predicted sites are, indeed, modified. Not only the conserved modifications (marked by solid arrows) but also the trypanosome species-specific modifications (marked by hollow arrows) exist. Interestingly, some modifications with no known guide RNAs (marked by dots) were also detected, suggesting that there are more modifications than we predicted. Indeed, earlier studies showed the existence of ~100 Nms on Crithidia rRNA (Gray 1979).

FIGURE 6.

Mapping of the modified nucleotides in rRNA. (A) Mapping 2′-O-methylations on small subunit rRNA using primer 1923. (B) Mapping 2′-O-methylations on a large subunit rRNA (5′ half) using primer 1425. (C) Mapping 2′-O-methylations on a large subunit rRNA (3′ half) using primer 385. Primer extension was performed using different concentrations of dNTPs (0.05, 0.5, and 5 mM) to detect the methylations. (D) Mapping of pseudouridines on a large subunit rRNA (3′ half) using primer 22269. RNA was treated with CMC (CMC+) or without CMC (CMC−), as described in Materials and Methods, and subjected to primer extension analysis. Extension products were analyzed on 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel next to DNA sequencing performed with the same oligonucleotides used in the primer extension assay. Partial sequences are given, and the modified nucleotides are indicated. The conserved modifications (in bold) are marked by solid arrows, whereas trypanosome-specific modifications are marked by hollow arrows. The dots indicate modifications that an snoRNA to direct these modifications was not identified in this study.

To examine whether the predicted U is actually pseudouridylated, we treated total RNA from T. brucei with CMC and performed primer extension with oligonucleotide complementary to the LSU 3′ half. In this method, the reverse transcriptase stops 1 nt before the modified base (Ofengand and Bakin 1997). Indeed, the predicted nucleotides (marked with arrows) are isomerized, as seen in Figure6D ▶. As in the case of methylations, trypanosome-species-specific as well as conserved modifications exist. The Ψ at positions 581 and 618 in the LSU 3′ half were identified, but the RNAs needed to target these modifications were not identified in this study.

DISCUSSION

In this study, a whole-genome approach was used to identify the repertoire of T. brucei C/D and H/ACA RNAs. The targets of the majority of these RNAs were found, and partial mapping of the modified nucleotides guided by these RNAs on rRNA was performed. The prevalent gene organization consists of gene clusters carrying a mixed population of both C/D and H/ACA-like RNAs repeated several times in the genome. Exceptions to this rule are clusters that are not repeated (but expressed) that carry a single snoRNA. The putative targets of the majority of the snoRNAs present in these clusters were found. They indicate the presence of numerous 2′-O-methyls relative to the trypanosome’s small genome. The amount of Ψs is not equal to the quantity of Nms found in yeast and mammals (Decatur and Fournier 2002). Surprisingly, almost half of the snoRNAs identified seem to guide trypanosome-species-specific modifications that do not exist in humans, yeast, and plants. However, the number of Nms and the genome organization of the snoRNA genes resemble plants more than other organisms. Most interestingly, trypanosome-species-specific Nm modifications that do not exist in yeast, humans, or plants were identified. These modifications were found in modification-rich functionally important domains but also outside them. The large number of Nms might be beneficial to the parasites in coping with the adverse environmental conditions encountered in cycling between the vertebrate and insect hosts. The large quantity of guide RNAs present in this relatively small genome suggests a central role of RNA-mediated regulation in these protozoan parasites.

The repertoire described compared to what we expect

The repertoire described here most probably represents most but not all of the small RNAs that guide modification in T. brucei. Only 84 Nms are predicted to exist on rRNA, based on this study, but early studies suggest the existence of as many as 100 Nms in Crithidia rRNA (Gray 1979). In addition, we have not yet identified any guide RNA that guides modification on trypanosome snRNAs such as scaRNA. scaRNAs are chimeric molecules carrying both C/D and H/ACA functions, which are localized in metazoa in special compartments near the nucleolus, the Cajal bodies (Richard et al. 2003). Modifications were mapped on trypanosome snRNAs (Li et al. 2000). We therefore expect to find snoRNAs that will guide these modifications. At this point, we cannot exclude the possibility that enzymes mediate many of these modifications. Indeed, in yeast, U2, Ψ35, and 44 are generated by enzymes Pus7p and Pus1p, respectively (Massenet et al. 1999; Ma et al. 2003). The recent finding that pseudouridylation of snRNAs can also be guided by conventional H/ACA snoRNAs (Kiss et al. 2004) raises the possibility that such RNAs may also exist in trypanosomes. In addition, trypanosomes may also use enzymatic modifications. Preliminary mapping of the Ψs on U2 snRNA in the pseudouridine synthase (Cbf5p) RNAi-silenced cells indicates that many of the known conserved modifications are not abolished or even changed during the elimination of the H/ACA-like RNA, suggesting that also in trypanosomes some of the modifications may be carried out by enzymes (S. Barth, A. Hury, and S. Michaeli, unpubl.).

Where are the rest of the expected guide RNAs “hiding” in the genome? Since our search was able to identify snoRNAs that are repeated within a chromosome, single-copy snoRNA genes may have escaped our searches. New snoRNAs might be found using experimental approaches. We have recently TAP-tagged RNA-binding proteins of both C/D and H/ACA-like RNA and are in the process of identifying the RNAs that are coimmunoprecipitated with these particle-specific proteins. At this point, we cannot exclude the possibility that, in fact, we have identified almost all of the C/D snoRNAs in this study and that enzymes are responsible for the remaining modifications on rRNA (12 Nms). Indeed, as can be seen in Figure6 ▶, we have identified modifications but we have not yet identified a cognate snoRNA to target these modifications. A recent study in yeast indicates that the Nm modification guided by snR52 is also enzymatically modified by methyltransferase (Spb1p) and that knocking out both these functions causes a growth defect, suggesting redundant mechanisms for modification of this site (Bonnerot et al. 2003). The homolog to snR52 was identified in this study (TB10C3C1). Our recent discovery of snoRNAi in T. brucei (Liang et al. 2003b) may enable us to examine in trypanosomes the existence of a similar redundant mechanism to modify rRNA.

Unique structural features of trypanosome snoRNAs

The only striking property of trypanosome C/D snoRNAs is that many of them are double-guiders and can potentially guide adjacent sites on rRNA. The trypanosome genome is ~30Mb, which is small relative to plants and mammals. The small genome and the large number of modifications may have selected the double-guide organization. The simultaneous formation of two guide duplexes may suggest that these snoRNAs have a chaperone function that is needed to control pre-rRNA folding. The trypanosome H/ACA possesses a unique structure compared to the molecules in most eukaryotes, since instead of being a double-guide molecule, most if not all of them are single-hairpin molecules. When the secondary structural features and compensatory changes in the secondary structure are examined, it will be possible to establish rules to specify these RNA molecules and to write an algorithm that will search for these RNAs in a whole-genome search. Since the discovery of these single Ψ-guide RNAs in trypanosomes, single-guiding RNAs were discovered in Archaea (Tang et al. 2002; Rozhdestvensky et al. 2003) and Euglena (Russell et al. 2004). In Euglena all the guide RNAs that are involved in guiding pseudouridylation also carry the AGA-box (Russell et al. 2004). Indeed, in yeast and humans the AGA sequence never appears naturally at the 3′ end of the molecule. It was recently suggested that the trypanosome and Euglena snoRNA resemble the 5′ end of the eukaryotic H/ACA RNA, since the H-box is, in fact, AGANNN (Russell et al. 2004). Moreover, it was already suggested that since both the trypanosome and Euglena diverged early in the eukaryotic lineage, their single Ψ-guide RNA may represent the primordial guide RNA that gave rise to the double-guiders later in evolution.

In Archaea (Bachellerie et al. 2002) as well as in humans (Kiss et al. 2002), there are molecules that carry several H/ACA-like domains and are most probably the “fusion” products of individual molecules. Such molecules have not yet been found in trypanosomes.

Genome organization compared to other eukaryotes

The genomic organization of snoRNA genes is very diverse in different eukaryotes (recently summarized in Uliel et al. 2004). The organization of trypanosome snoRNAs resembles mostly the organization of plants because the genes are clustered and the clusters carry a mixture of both H/ACA and C/D snoRNAs (Brown et al. 2003a). The similarity between plants and trypanosomes is intriguing; in fact, it was recently found that Trypanosoma and Leishmania contain several “plant-like” genes. These genes most probably originated from endosymbiosis with an archaic organelle that was once common to plants and trypanosomes but was later lost during evolution in trypanosomes (Hannaert et al. 2003). Recently, the genome organization of Euglena snoRNA genes was studied, and it is suggested that as in trypanosomes, these genes are also clustered and the clusters are composed of both C/D and H/ACA-like RNA. These clusters are also repeated (Russell et al. 2004).

Almost all clusters encoding for snoRNAs identified in this study are repeated, suggesting that the level of expression is dependent on the number of the copies of the repeat. Like many protein-coding genes in trypanosomes, the repeat nature of the snoRNA cluster represents a mechanism of coping with the absence of Pol II promoters (Clayton 2002). The high degree of expression of these RNAs is therefore mediated by gene multiplicity. Interestingly, there are also snoRNA clusters that are single-copy genes, yet their RNAs are also properly expressed (Fig. 2 ▶). Several repeats contain an accompanying protein-coding gene. In both cases, the genes (GP63, GLK1) have no direct relationship to snoRNA or RNA metabolism.

Additional snoRNA genes may still be identified in the future, since as previously discussed, the full repertoire of H/ACA and C/D snoRNAs is most probably incomplete. Perhaps one should expect to find repeats that carry only H/ACA RNA; these would not have been identified in our searches because we used the SnoScan program (Lowe and Eddy 1999), which identifies only the C/D snoRNAs. The identification of such H/ACA gene clusters awaits the development of an algorithm that will be able to predict trypanosome H/ACA-like RNAs on a genomic scale. It is also possible that the remaining missing snoRNAs, for instance, the snoRNAs that direct modification on snRNAs, are present as single-copy genes. Indeed, the number of snRNA molecules to be guided is often 100 times less abundant than rRNA, and therefore single-copy genes may suffice in supplying the need for snRNAs modification.

The biological role of modifications and why Nms are so abundant in trypanosomes

In mammals, there are ~93–95 sites of methylation. However, in yeast, there are only 55 such modifications. The estimated number of such modifications in trypanosomatids is ~95–100 (Gray 1979) and resembles the number found in plants and vertebrates (Brown et al. 2003a). Surprisingly, in Euglena, as in trypanosomes, the rRNA is extensively modified, and the estimated number of modifications is 150 Nms and 70 Ψs (Russell et al. 2004). The increased number of methylations on plant rRNA was rationalized by the fact that plants are exposed to large temperature changes during which the ribosomes must be produced and remain active. Also in hyperthermophilic Archaea, there is a correlation between growth at elevated temperatures and the number of Nms in the rRNA (Bachellerie et al. 2002). We initially hypothesized that since trypanosomes undergo temperature changes during their life cycle, from 26°C in the insect host to 37°C in the mammalian host, the hypermodification is related to the need to preserve ribosomal activity under adverse environmental conditions. However, Euglena is not a parasite that cycles between different hosts, but like plants, is exposed to major temperature changes in nature. In addition, like trypanosomes, Euglena diverged very early from the eukaryotic lineage (Sogin et al. 1986), and its large rRNA is fragmented (Schnare and Gray 1990). Each of the unique properties shared by both organisms as well as their early divergence from the eukaryotic lineage may have been selected for the generation and conservation of the large number of Nms on rRNA found in these organisms. It will be very interesting to compare the positions of the trypanosome-species-specific modifications in Euglena and determine whether they are located at similar positions.

Of great interest is the large number of predicted Nms that are species-specific. These modifications are clustered together in the most conserved structural domains. Also of interest is the finding that relatively many adjacent nucleotides are methylated. In several cases such as TB5Cs1C1, TB3Cs2C1, and TB8Cs2C1, the same snoRNA can direct the methylation on two adjacent sites. It is now well-accepted that eliminating a single modification does not have a dramatic effect on ribosome function, which suggests that most individual modifications contribute a small non-essential benefit and only when numerous modification exist is a large benefit provided (Decatur and Fournier 2003). The increasing number of modifications in the conserved functional domains may stabilize the ribosome and help it to function even under adverse conditions. Indeed, the sites of modifications are clustered in domains where specific translation events take place (Decatur and Fournier 2002).

In this study we identified a large number of H/ACA-like RNAs that appear to be species-specific. However, this may change when more of these guide RNAs are identified in other organisms.

Novel trypanosome snoRNAs with non-nucleolar RNA targets

One of the most interesting H/ACA-like molecules discovered in trypanosomatids is SLA1, which directs pseudouridylation on the SL RNA. This RNA was initially discovered because of its efficient cross-linking to SL RNA and at that time was proposed to represent the U5 snRNA (Watkins et al. 1994). Although it is clear that SLA1 is, indeed, an H/ACA-like RNA (Liang et al. 2002), its role in SL RNA biogenesis is still an open question. Also, it is not yet clear if the main function of SLA1 is to direct the modification at position −12 or to serve as a chaperone for the SL RNA during its early steps of biogenesis before assembly with Sm proteins (Mandelboim et al. 2003).

Additional snoRNAs were revealed in the clusters described in this study that deviate from the canonical structures. TB10Cs1C2 and the 270-nt RNA TB11Cs2C3 (in the SLA1 locus) are longer than the canonical guide RNAs. In addition, these RNAs obey neither the structure of C/D nor the H/ACA-like RNA and must therefore have other functions. It will be of interest to find out if these RNAs guide the cleavage of pre-rRNA. Structurally, the 270-nt RNA highly resembles the Euglena RNA Eg-h1 recently described (Russell et al. 2004). In both cases, RNA possesses an ACA-box at the 3′ end and an H-like box located in a single-stranded region. This kind of molecule may represent the primordial H/ACA RNA already present in protists, which may have evolved from a fusion of single stem–loop RNAs.

Also of great interest is the TB11Cs2C2 snoRNA that appears in the SLA1 locus and the snoRNAs that have the potential to guide modifications in the ITS (Tb10Cs2C1). So far, all the modifications were mapped to functional domains within the mature RNA. In fact, although modification takes place on the nascent elongating transcript, no modification was ever found in the transcribed spacer that is removed from the pre-RNA during processing. This novel type of snoRNA may serve as a chaperone during rRNA processing to direct or accelerate proper RNA folding. It remains to be seen if the position on the pre-rRNA is, indeed, modified.

Recently we found that snoRNAs can be silenced by an RNA interference-like mechanism (Liang et al. 2003b). In Leptomonas and Leishmania, the silencing of snoRNA was achieved by overexpressing of antisense RNA, whereas in T. brucei, the silencing was facilitated by in vivo production of double-stranded RNA (Liang et al. 2003b). The mechanism of silencing may differ among different trypanosomatid species. However, this finding opens up the possibility of elucidating the function of individual snoRNAs or specific modifications described in this study.

In summary, in this study we used bioinformatics and experimental tools to investigate the repertoire of snoRNAs that guide modification in T. brucei. The results of the past studies suggest that we are at the tip of a large iceberg, and future studies in elucidating the snoRNomics of trypanosomes and other eukaryotes promise to further remain a fascinating branch of RNomics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides

TBcr03, 5′-CGGTATCTTTCTGATCCTCAG-3′, antisense complementary to snoRNA TB3Cs2C1, from position 51 to 71;

TB5Cs1, 5′-TGTTTTCAATCGCAGGGTCC-3′, antisense, complementary to snoRNA TB5Cs1C1, from position 38 to 57;

TB6Cs2-A, 5′-ATGCCCGTTACGGAACTCT-3′, antisense, complementary to snoRNA TB6Cs2C1, from position 34 to 52;

TB5H1, 5′-CGCACGTGCTTCGTACCG-3′, antisense, complementary to snoRNA TB10Cs3H1, from 41 to 58;

TB9Cs5-A, 5′-TCTTCACATTTGCTAATTCA-3′, antisense, complementary to snoRNA TB9Cs5C2, from position 33 to 52;

TBC-4, 5′-ATAGAGTTCACAGTTGCA-3′, antisense, complementary to snoRNA TB9Cs2C5, from position 59 to 76;

TBsno-H-1, 5′-AATTCTCGGACCACGTGA-3′, antisense, complementary to snoRNA TB9Cs2H1, from position 58 to 75;

2-CH-2, 5′-CGCGGGTCCGATTGAG-3′, antisense, complementary to snoRNA TB6Cs1H2, from position 51 to 66;

2-HH-3, 5′-AACCTCAATGGGTATC-3′, antisense, complementary to snoRNA TB6Cs1H4, from position 54 to 71;

1425, 5′-ATCGCCTGCTCCGCTTAC-3′, antisense, complementary to rRNA large subunit 5′ half, from position 1425 to 1442;

385, 5′-GGCAGAAATCAGTTTGCG-3′, antisense, complementary to rRNA large subunit 3′ half, from position 385 to 402;

1923, 5′-ATTGTAGTGCGCGTGTCG-3′, antisense, complementary to rRNA small subunit, from position 1923 to 1940; and

22269, 5′-ACCTCCAAAGTCGCCGCA-3′, antisense, complementary to rRNA large subunit 3′ half, from position 637 to 654.

Prediction of the targets on rRNA

The potential targets (2′-O-methylation) in rRNA were determined using the computer program BestFit (from the GCG package) searching for complementarity to rRNA that complies with the +5 guiding rule. Additionally, the targets were also predicted based on the data available from the yeast homologs. To predict the pseudouridines guided by H/ACA RNAs, secondary structure of H/ACA RNA was folded using the MFOLD program (http://www.bioinfo.rpi.edu/applications/mfold/old/rna/form1.cgi), and the sequences from the internal loop were used to search for complementarity with rRNA, based on the guiding rule established in yeast mammals and plants (http://www.bio.umass.edu/biochem/rna-sequence/Yeast_snoRNA_Database/snoRNA_DataBase.html; http://bioinf.scri.sari.ac.uk/cgi-bin/plant_snorna/conservation).

Prediction of the secondary structure of rRNA

The secondary structure of T. brucei rRNA was derived from http://www.icmb.utexas.edu. The sequence of the LSU is from EMBL X14553, X05682, X04986. The T. brucei SSU secondary structure was obtained by superimposing the T. brucei sequence (derived from chromosome 1, positions 794117–79636) on the L. major RNA present at the same site previously mentioned.

RNA preparation and primer extension analysis

RNA was prepared from T. brucei cells using TRI-Reagent (Sigma). Primer extension analysis was performed as described (Liang et al. 2001; Xu et al. 2001) using 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotides specific to target RNAs, as indicated in the figure legends. The extension products were analyzed on 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel and visualized by autoradiography.

Mapping of the modified nucleotides

2′-O-Methylations on rRNA were mapped using a primer extension with a different level of dNTPs, as described in Xu et al. (2001). Pseudouridines were examined after n-cyclohexyl-N′-β-(4-methylmorpholinium) ethylcarbodiimeide p-tosylate-(CMC) modification, as described in Liang et al. (2001) using primers specific to the relevant region in rRNA. Primer extension products were analyzed on 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel, next to sequencing reactions performed using the same primer.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation and by an International Research Scholars grant from the Howard Hughes Foundation to S.M. We are grateful to the members of the TriTryp sequencing consortium (Karolinska Institute, Seattle Biomedical Research Institute, The Institute for Genome Research and Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute) for allowing us access to the L. major, T. brucei, and T. cruzi genome sequence data prior to publication. Annotation of the snoRNA genes can be found at http://www.genedb.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.7174805.

REFERENCES

- Bachellerie, J.P., Cavaille, J., and Hüttenhofer, A. 2002. The expanding snoRNA world. Biochimie 84: 775–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson, G. 1999. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnerot, C., Pintard, L., and Lutfalla, G. 2003. Functional redundancy of Spb1p and a sRN52-dependent mechanism of the 2′-O-ribose methylation of a conserved rRNA position in yeast. Mol. Cell 12: 1309–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolin, M.L., Ganot, P., and Kiss, T. 1999. Elements essential for accumulation and function of small nucleolar RNAs directing site-specific pseudouridylation of ribosomal RNAs. EMBO J. 18: 457–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.W., Echeverria, M., and Qu, L.H. 2003a. Plant snoRNAs: Functional evolution and new modes of gene expression. Trends Plant Sci. 8: 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.W., Echeverria, M., Qu, L.H., Lowe, T.M., Bachellerie, J.P., Hüttenhofer, A., Kastenmayer, J.P., Green, P.J., Shaw, P., and Marshall, D.F. 2003b. Plant snoRNA database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 432–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaille, J. and Bachellerie, J.P. 1996. Processing of fibrillarin-associated snoRNAs from pre-mRNA introns: An exonucleolytic process exclusively directed by the common stem-box terminal structure. Biochimie 78: 443–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, C.E. 2002. Life without transcriptional control? From fly to man and back again. EMBO J. 21: 1881–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decatur, W.A. and Fournier, M.J. 2002. rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27: 344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2003. RNA-guided nucleotide modification of ribosomal and other RNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 695–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, P.P., Omer, A., and Lowe, T. 2001. A guided tour: Small RNA function in Archaea. Mol. Microbiol. 40: 509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, D.A. and Baserga, S.J. 1998. The U14 snoRNA is required for the 2′-O-methyaltion of the pre-18S rRNA in Xenopus oocytes. RNA 4: 195–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, D.A., Chen, A.A., Wormsley, S., and Baserga, S.J. 2000a. The genes for small nucleolar RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei are organized in clusters and are transcribed as a polycistronic RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 2855–2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, D.A., Wormsley, S., Lowe, T.M., and Baserga, S.J. 2000b. Fibrillarin-associated box C/D small nucleolar RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. Sequence conservation and implications for 2′-O-ribose methylation of rRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 14767–14776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]