Abstract

The lymphoid enhancer factor-1 LEF1 locus produces multiple mRNAs via alternative promoters. Full-length LEF-1 protein is produced via translation of an mRNA with a 1.2-kb, GC-rich 5′-untranslated region (UTR), whereas a truncated LEF-1 isoform is produced by an mRNA with a short, 60-nucleotide (nt) 5′-UTR. Full-length LEF-1 promotes cell growth via its interaction with the WNT signaling mediator β-catenin. Truncated LEF-1 lacks the β-catenin binding domain and opposes WNT signaling as a competitive inhibitor for WNT response elements. In this study we tested the hypothesis that the long, GC-rich 5′-UTR within the full-length LEF1 mRNA contains an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). Using a dicistronic vector in transient DNA transfections, we show that the LEF1 5′-UTR mediates cap-independent translation. Additional experiments involving a promoter-less dicistronic vector, Northern blot analysis, and transient transfections of dicistronic mRNAs into cultured mammalian cells compromised for cap-dependent translation demonstrate that the 5′-UTR of full-length LEF1 mRNA contains a bona fide IRES. Deletion analysis of the 5′-UTR shows that maximal IRES activity requires the majority of the 5′-UTR, consistent with the notion that cellular IRESs require multiple modules for efficient activity. This study demonstrates that full-length LEF1 mRNA has evolved to utilize a cap-independent mechanism for translation of full-length LEF-1, whereas the truncated isoform is produced via the canonical cap-dependent ribosome scanning mechanism.

Keywords: LEF-1, IRES, WNT signaling, cancer, 5′-UTR, translation

INTRODUCTION

Lymphoid enhancer factor-1 (LEF-1), a LEF/TCF transcription factor, mediates WNT signal control of cell cycling and differentiation by recruiting the transcription activator β-catenin to target genes (Fig. 1A). LEF-1 regulates genes involved in cell growth in undifferentiated, mitotically active cells at numerous sites in the embryo (e.g., tooth buds, mammary buds, trigeminal ganglia) as well as those in post-natal tissues (e.g., hair follicles, T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes). Immature B lymphocytes missing the LEF1 gene do not progress through the cell cycle efficiently and are prone to apoptosis before they can fully mature and exit the bone marrow (Reya et al. 2000). Normally LEF-1 expression and activity are highly regulated. As cells mature and become quiescent, LEF-1 transcription and translation are down-regulated. In addition, LEF-1 protein activity is balanced by the expression of a truncated LEF-1 polypeptide that lacks the β-catenin binding domain and thus competes for binding to WNT target genes. This smaller, inhibitory isoform is produced via a second promoter located in the second intron of the LEF1 locus (Fig. 1A; Hovanes et al. 2001; T.W.H. Li, T.R. Ting, N. Yokoyama, M.v.d. Wetering, and M.L. Waterman, in prep.).

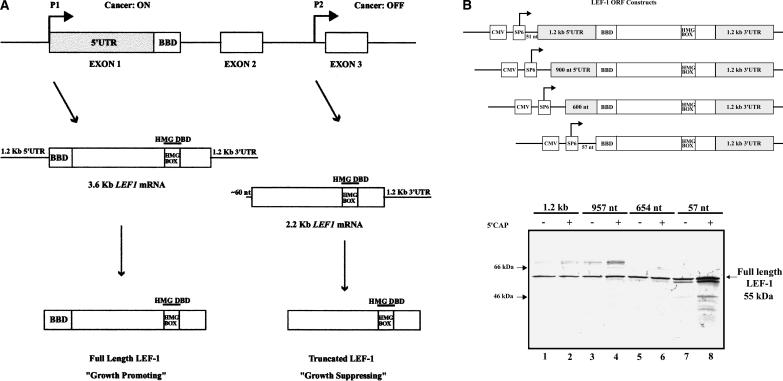

FIGURE 1.

The 5′-UTR of LEF1 mRNA supports translation of full-length LEF-1 protein in vitro. (A) Schematic representation of exons 1–3 of the LEF1 locus. The two promoters that generate the full-length and truncated LEF-1 isoforms are designated as P1 (Promoter 1) and P2 (Promoter 2), respectively. The mRNA produced by P1 is aberrantly activated in colon cancer, whereas P2 is not active. The β-catenin binding domain (BBD) in the full-length isoform is labeled, and “HMG DBD” designates the DNA binding domain present in both isoforms. (B) Schematic representation of the expression plasmids used to express the LEF-1 ORF. The LEF-1 ORF, the entire 1.2 kb as well as successive 5′-deletions of the 5′-UTR and the 1.2-kb 3′ UTR were cloned into pCS2 expression plasmid. The construct containing no LEF1 5′-UTR sequence contains 57 nucleotides of vector sequence upstream of the BBD, whereas the other constructs contain 51 nt of vector sequence in between the SP6 promoter and the BBD. These constructs were transcribed in vitro +/− cap analog and subsequently translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL) as described in the Materials and Methods. (C) Autoradiography of the SDS-PAGE gel used to resolve the in vitro translation reactions performed in RRL. The arrow denotes full-length LEF-1 protein, which migrates at 55 kDa. Rainbow molecular weight protein marker (Amersham) was loaded for size determination. Intensity of the bands was determined using Quantity One software.

WNT signaling has a powerful effect on cell growth, and this is underscored by the fact that numerous types of cancers derive from overactive WNT signaling (Bienz and Clevers 2000; Polakis 2000). The strongest link is colon cancer, where somatic mutation of WNT signaling components causes hyperactive, constitutive signaling and cell transformation. Interestingly, LEF1 is aberrantly expressed in > 80% of these cancers (T.W.H. Li, T.R. Ting, N. Yokoyama, M.v.d. Wetering, and M.L. Waterman, in prep.). However, only the mRNA with the long 5′-UTR is aberrantly transcribed. The promoter that produces the shorter LEF1 mRNA is not expressed. The loss of balanced expression may have important effects on cancer progression. Indeed, normal embryo fibroblasts are transformed when a full-length LEF-1 fusion protein with a constitutively active transcription activation domain is overexpressed (Aoki et al. 1999).

Until now, studies of the regulation of LEF1 activity have focused on transcription of its two alternative promoters and the opposing actions of their respective full-length and truncated protein products. However there are important post-transcriptional events that modify LEF-1 action; for example, post-translational modification of full-length LEF-1 by SUMO modifies both its activity and stability (Sachdev et al. 2001). In addition, LEF-1 may also be post-transcriptionally regulated, because as noted by DasGupta and Fuchs (1999), there is a discordance between LEF1 mRNA, LEF-1 protein, and WNT signaling activity in the differentiating cells at the base of hair follicles. Furthermore, as a result of our own studies to map the transcriptional start sites of both LEF1 promoters, we have noted unusual and contrasting features of the 5′-UTRs. Whereas the intronic promoter produces a truncated LEF1 mRNA with a 60-nt 5′-UTR, the first promoter produces an mRNA with an unusually long 5′-UTR; the UTR is 1.2 kb in length, GC-rich, and surprisingly devoid of AUG codons in any frame except for one. A single upstream AUG occurs halfway through the 5′-UTR and marks the beginning of a conserved upstream open reading frame (uORF). Based on these dramatically different features of the 5′-UTRs, we hypothesize that the opposing forms of LEF-1 are produced via different translation mechanisms.

In eukaryotic cells, translation initiation of most mRNAs is mediated by ribosome scanning whereby the translation initiation complex recognizes and binds to the cap structure at the 5′-end of the mRNA and scans the mRNA in a 5′ → 3′ direction until the first AUG codon within an optimal context is encountered (Hellen and Sarnow 2001; Kozak 2002). On average, eukaryotic mRNAs contain 5′-UTRs that are 50–100 nt long, compatible with ribosome scanning in cap-dependent translation mechanisms (Hellen and Sarnow 2001). The mRNA encoding the truncated LEF-1 isoform with a short 5′-UTR is likely translated by this canonical mechanism. In contrast, the length and GC content of the 5′-UTR of the mRNA for full-length LEF-1 suggest that it is likely to have extensive secondary structure. These features could be inhibitory to efficient ribosomal scanning (Kozak 2002). Therefore, to produce LEF-1 protein, the translation apparatus may use an alternative mechanism of translation initiation such as ribosome shunting or internal ribosome entry.

IRES (internal ribosome entry site) elements were first discovered and characterized in RNA genomes of picornaviruses that contain long 5′-UTRs that naturally lack 5′-terminal cap structures (Jang et al. 1988; Pelletier and Sonenberg 1988; Pelletier et al. 1988). IRES elements have also been identified in a number of eukaryotic cellular mRNAs, some of which encode proto-oncogenes, growth factors, receptors, and transcription factors. Many IRES-containing cellular mRNAs appear to be regulated during the cell cycle and or during various stress situations at the translational level (Willis 1991; Geballe and Morris 1994; Hellen and Sarnow 2001; Sonenberg and Pyronnet 2001; Vagner et al. 2001; Qin and Sarnow 2004). The mechanisms by which these cellular IRESs facilitate the initiation of translation are not well understood, since those discovered thus far differ in their primary sequences from each other and those of viral origin (Hellen and Sarnow 2001; Vagner et al. 2001; Martinez-Salas et al. 2002). However, like the full-length LEF1 mRNA, many eukaryotic mRNAs that contain IRESs possess long, GC-rich 5′-UTRs. Another notable feature is that IRESs are found in 5′-UTRs that contain multiple upstream AUGs (or CUGs) (Hellen and Sarnow 2001). As noted above, the LEF1 1.2-kb 5′-UTR contains only one upstream AUG (although it has nine CUGs). Thus, the LEF1 5′-UTR shares features found in other characterized cellular IRESs, but it is also unique. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that translation of full-length LEF-1 protein is mediated through internal ribosome entry. Using a dicistronic vector in DNA and RNA transient transfections, we identified a highly active IRES element within the LEF1 5′-UTR. Another feature of several cellular IRESs (those contained within the mRNAs for c-MYC, L-MYC, Rbm3, VEGF, Gtx, and a voltage-gated potassium channel, Kv1.4) is the requirement of multiple modules for maximal activity (Huez et al. 1998; Stoneley et al. 1998; Chappell et al. 2000, 2001; Jang et al. 2004; Jopling et al. 2004). It appears that the LEF1 IRES also has multiple, independent elements that together account for cell type differences in translation initiation. Thus, like other important regulators of cell growth, full-length, oncogenic LEF-1 protein is produced by a cap-independent translation mechanism, a mechanism distinct from that utilized to translate the truncated, growth-suppressing-isoform.

RESULTS

The 5′-UTR of LEF1 mRNA supports translation of full-length LEF-1 in vitro

To investigate the role the 5′-UTR may play in the translation of full-length LEF-1, we examined LEF-1 protein expression in the presence and absence of the 1.2-kb 5′-UTR in rabbit reticulocyte lysate. The entire LEF-1 open reading frame, as well as the entire 1.2-kb 5′- and 3′-UTRs, were cloned into a eukaryotic expression vector containing the SP6 promoter. In addition, constructs containing successive 5′-deletions (957 nt, 654 nt, 57 nt) were generated (depicted in Fig. 1B) and used to synthesize capped and uncapped transcripts for translation in the reticulocyte lysate.

Figure 1C shows that the 1.2-kb 5′-UTR permitted translation of full-length LEF-1 protein. Additionally, the presence of a cap structure did not result in more efficient protein synthesis, since quantitation of the bands revealed that both transcripts generated relatively equal levels of protein (Fig. 1C, cf. lanes 1 and 2). Deletion of the 5′-UTR to 654 nt resulted in slightly higher levels of protein (lane 6 contains 2 × the amount of protein as lanes 1 and 2). Further deletion of the 5′-UTR to a length equivalent to that of the shorter LEF1 mRNA resulted in significantly higher production of LEF-1 protein, especially in the presence of a cap structure (lane 8 contains ~7 × the amount of protein as lanes 1 and 2). Therefore, in the rabbit reticulocyte lysate, a long 5′-UTR allows synthesis of LEF-1 protein and is insensitive to the presence of a cap structure. In contrast, a cap allows for more efficient translation of shorter 5′-UTRs, demonstrating that in our in vitro assay, cap-dependent scanning by ribosomes is the dominant mode of translation for short 5′-UTRs.

Higher-molecular-weight polypeptides were also evident among the in vitro translation products of LEF1 mRNAs (Fig. 1C, lanes 1–4). Other than those that are sumo-modified (Sachdev et al. 2001), there is no evidence of higher-molecular-weight LEF-1 isoforms thus far. The LEF1 5′-UTR contains several alternative translation initiation codons (one AUG and nine CUGs) that are in frame with the authentic translation start site. These higher-molecular-weight products may be the result of aberrant start codon recognition. The rabbit reticulocyte lysate lacks several RNA-binding proteins that normally bind the mRNA and block ribosomes from initiating translation upstream of the authentic start codon (Svitkin et al. 1996). Addition of a cap resulted in slightly more translation initiation at these sites. Since this effect is seen when the start codons are within 300–400 nt of the 5′-end, we conclude that this background level of translation is due to cap-dependent ribosomal scanning.

The LEF1 5′-UTR mediates internal ribosome entry in mammalian tissue culture cell lines

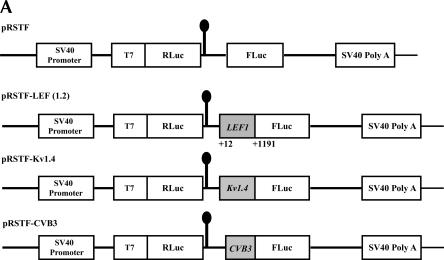

To investigate the possibility that the LEF1 5′-UTR may contain an IRES, we cloned the entire 1.2 kb of the LEF1 5′-UTR into a dicistronic vector, pRSTF, to generate pRSTF-LEF (1.2) (Fig. 2A). This vector contains the coding region for the Renilla Luciferase (RLuc) gene followed by an intercistronic region that contains a multiple cloning site and an additional downstream cistron which encodes Firefly Luciferase (FLuc). A hairpin structure is present in the intercistronic region to inhibit ribosomal read-through, or reinitiation, from the first cistron to the downstream cistron. Translation of the upstream cistron (RLuc) relies on cap-dependent translation, whereas translation of FLuc relies on the presence of an internal ribosome entry site. Plasmid DNAs corresponding to the empty dicistronic vector, as well as pRSTF-LEF (1.2), were transfected into HeLa (cervical carcinoma), SW480 (colon cancer), and COS-1 (monkey kidney) cells (Fig. 2B). For positive controls, we analyzed a viral and a cellular IRES in the dicistronic assay: the pRSTF vector containing either the 5′-UTR from coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) or from Kv1.4 mRNA, a mouse voltage-gated potassium channel (Fig. 2A, pRSTF-CVB3 and pRSTF-Kv1.4) (Jang et al. 2004). The CVB3 5′-UTR is ~740 nt in length; that of Kv1.4 is ~1.2 kb. In all three cell lines, the LEF1 5′-UTR mediated translation of the downstream FLuc cistron. In HeLa(S) and SW480 cells, the LEF1 5′-UTR exhibited ~30-fold IRES activity compared to the empty vector. The highest activity was observed in COS-1 cells, where LEF1 was 60-fold more active than the empty vector. In addition, there was striking variation in the relative activities of the three dicistronic reporters in the three different cell lines. Such variation suggests that cleavage by ubiquitous RNases is unlikely to be the cause of FLuc expression, as was recently suggested (Kozak 2003). This variation, however, could be due to cryptic promoters or cryptic splicing events that vary in activity by cell line. To examine the integrity of the dicistronic transcripts, we performed a Northern blot analysis on RNA isolated from HeLa cells transfected with the dicistronic constructs.

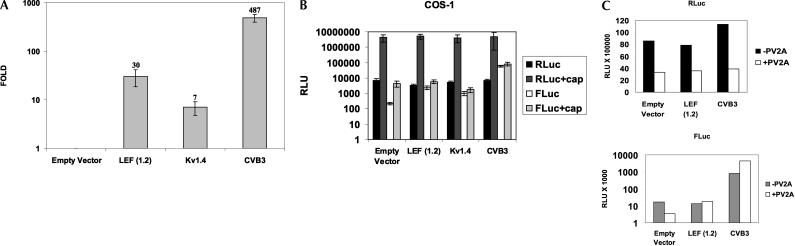

FIGURE 2.

The LEF1 5′-UTR mediates internal ribosome entry in mammalian tissue culture cell lines. (A) Schematic representation of the dicistronic vector pRSTF used to examine IRES activity in transient transfections and reporter gene assays. Approximately 1.2 kb (+12 to +1191 relative to the P1 transcription start site) of the LEF1 5′-UTR was amplified via PCR and subcloned into the intercistronic region of pRSTF in frame with the translation start site of FLuc to generate pRSTF-LEF (1.2). The constructs pRSTF-Kv1.4 and pRSTF-CVB3 containing ~1.2 kb and 740 nucleotides of 5′-UTR sequence from Kv1.4 mRNA and coxsackievirus (CVB3), respectively were used as positive controls (Jang et al. 2004). (B) The dicistronic constructs were transiently transfected into COS-1 (monkey kidney), SW480 (colon cancer), and HeLa (cervical carcinoma) cells. A dual luciferase reporter assay was performed 20–24 h post-transfection to measure Renilla and Firefly Luciferase activities. IRES activity was calculated as the ratio of Renilla (RLuc):Firefly (FLuc), and the y-axis on the graphs represents the fold elevation over empty vector. (C) The dicistronic constructs were transiently transfected into HeLa (S) cells. Total RNA was isolated, selected on oligo(dT) cellulose, and analyzed via Northern blot. Transcripts containing FLuc-coding sequence were detected using a [32P]-radiolabeled probe. The dicistronic transcripts are denoted by an asterisk (*), and their respective sizes are indicated. NT designates mRNA isolated from nontransfected cells.

Figure 2C (lane 2) shows that the dicistronic LEF1 transcript is intact, and there is no evidence of any smaller transcripts that may have been generated by cryptic promoters, splice sites, or RNases. Smaller transcripts are detected in the lanes containing Kv1.4 and CVB3 dicistronic vectors. These smaller mRNAs are thought to be derived from cryptic splicing (Jang et al. 2004), but are not evident on a Northern blot performed on mRNA isolated from COS-1 cells (Fig. 3B). Although the Northern blot analysis is not sensitive enough to detect very low levels of monocistronic transcripts, it does reveal that the primary mRNA is the dicistronic transcript; therefore, we predict that the majority of the FLuc activity observed is generated from this mRNA. Still, if cryptic promoter(s) are weak, a minor population of transcripts not detected by Northern blot analysis could be solely responsible for the expression that we observe. We therefore subcloned the LEF1 5′-UTR into a modified, promoter-less dicistronic vector.

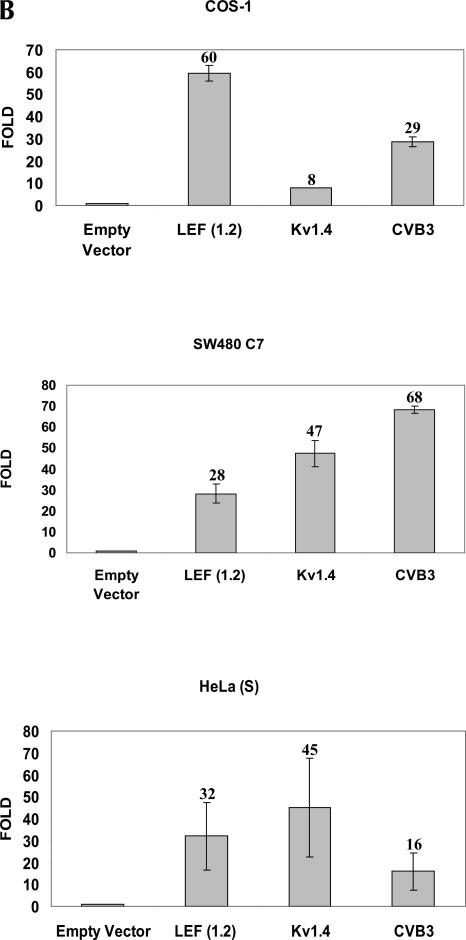

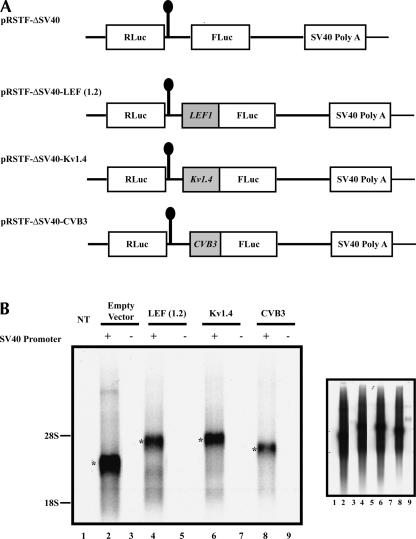

FIGURE 3.

Promoter activity does not significantly contribute to FLuc expression. (A) Schematic representation of the modified, promoter-less dicistronic constructs (Jang et al. 2004). Approximately 1.2 kb of the LEF1 5′-UTR was subcloned into the modified vector to generate pRSTF-ΔSV40-LEF (1.2) as described in the Materials and Methods. The constructs pRSTF-ΔSV40-Kv1.4 and pRSTF-ΔSV40-CVB3 are described by Jang et al. (2004). (B) The promoter-less dicistronic constructs, as well as the intact dicistronic constructs, were transiently transfected into COS-1 cells; total RNA was isolated and oligo(dT) selected and analyzed by Northern blot using a radiolabeled probe to the FLuc coding sequence. NT, lane 1, designates mRNA isolated from nontransfected cells. The asterisks indicate the dicistronic transcripts. The right panel is an overexposure of the same Northern blot. (C) The promoter-less dicistronic and intact dicistronic constructs were cotransfected with a β-galactosidase expression plasmid into COS-1cells. FLuc activity was measured 20–24 h post-transfection, and a β-galactosidase reporter gene assay was used to normalize FLuc activity. The y-axis represents normalized FLuc relative light units (RLUs). The open bars represent the activity of the intact dicistronic constructs; the black bars represent that of the promoter-less dicistronic constructs.

Cryptic promoter activity does not make a significant contribution to FLuc expression

The dicistronic vector, pRSTF, contains the SV40 promoter that is used to drive transcription of the dicistronic mRNA. We deleted the SV40 promoter to generate a promoter-less dicistronic vector, pRSTF-ΔSV40, so that we could compare the activity of this modified vector to that of the intact vector (Jang et al. 2004). If a cryptic promoter generates monocistronic transcripts that are responsible for the FLuc activity observed in the DNA transfections, we expect the ΔSV40 dicistronic vector containing the LEF1 5′-UTR (pRSTF-ΔSV40-LEF [1.2]) to produce significant levels of FLuc activity. Figure 3A shows a schematic of the modified dicistronic constructs. As controls, the 5′-noncoding regions of coxsackievirus (CVB3) and Kv1.4 were examined in this promoter-less vector. The constructs were transiently transfected into COS-1 cells and analyzed by Northern blot. Figure 3B demonstrates that in the absence of the SV40 promoter, dicistronic mRNAs are not expressed. In addition, smaller mRNA species are not evident on this blot (even when overexposed), although the RNA was isolated from a cell line in which the LEF1 5′-UTR demonstrated high FLuc activity. The promoter-less constructs were cotransfected with a β-galactosidase expression plasmid into COS-1 cells to serve as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Figure 3C shows that deletion of the SV40 promoter resulted in no FLuc activity from the empty vector, the 5′-UTR of Kv1.4, or the 5′-UTR of CVB3. This is consistent with the fact that these 5′-UTR sequences do not mediate promoter activity. In contrast, the LEF1 5′-UTR exhibited very low levels of FLuc activity, suggesting that this sequence may contain a weak Pol II promoter. In data not shown, we confirmed that there is an RNA polymerase II promoter between +280 and +640 relative to the main start site of transcription. This fragment contains bona fide, independent promoter activity. In addition, Filali et al. (2002) identified transcription start sites scattered throughout the LEF1 5′-UTR region when the UTR was transiently transfected into cells. Collectively, these dispersed start sites amount to low but detectable levels of 3.0-kb LEF1 transcripts on Northern blots, especially in cancer cell lines where LEF1 expression is aberrantly activated (Hovanes et al. 2001). Thus, the detected promoter activity is authentic. The transcripts generated by this weak promoter are predicted to encode ~800–900 nt of GC-rich 5′-UTR. As we demonstrate below, such transcripts are predicted to also be translated via cap-independent mechanisms.

Although the portion of FLuc activity we now attribute to an internal Pol II promoter varies in the three cell lines tested, its overall contribution to FLuc expression is minor. It represents only 2% of the total activity observed with the intact dicistronic construct in COS-1 cells. Thus, 98% of the luciferase activity exhibited by the intact dicistronic vector containing the LEF1 5′-UTR is due to a putative IRES. A slightly higher, but still minor, contribution to FLuc expression by the LEF1 promoter was observed in SW480 and HeLa(S) cells (data not shown). Overall, results from DNA transient transfections using the wild-type and promoter-less dicistronic constructs show that the LEF1 5′-UTR contains an internal ribosome entry site.

Although DNA transfections of a dicistronic vector are useful in determining whether a sequence contains an IRES, there is criticism that this method is inadequate because cells transfected with a DNA dicistronic vector may give rise to transcripts generated by aberrant splicing or cryptic promoters and could lead to misinterpretation of IRES activity (Van Eden et al. 2004). We have established that promoter activity is not responsible for most of the FLuc expression and argue that specific RNase cleavage is also unlikely. Nevertheless, we used more stringent methods in the form of RNA transfections to address the possibility of cryptic splicing.

The LEF1 5′-UTR exhibits bona fide IRES activity in the cytoplasm

Dicistronic mRNAs were synthesized in vitro and subsequently transfected into COS-1 cells (Fig. 4A), the cell line in which the highest IRES activity had been observed in the corresponding DNA transfections. RNA transfections ensure that only the dicistronic mRNA is introduced into the cytoplasm of the cell (Van Eden et al. 2004); therefore, the possibility of monocistronic transcripts generated by cryptic promoters or aberrant splicing is eliminated.

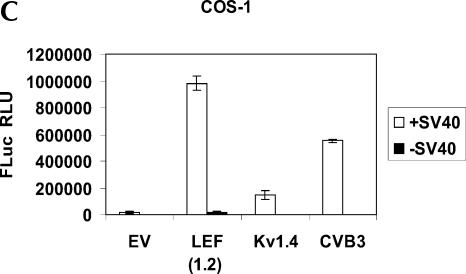

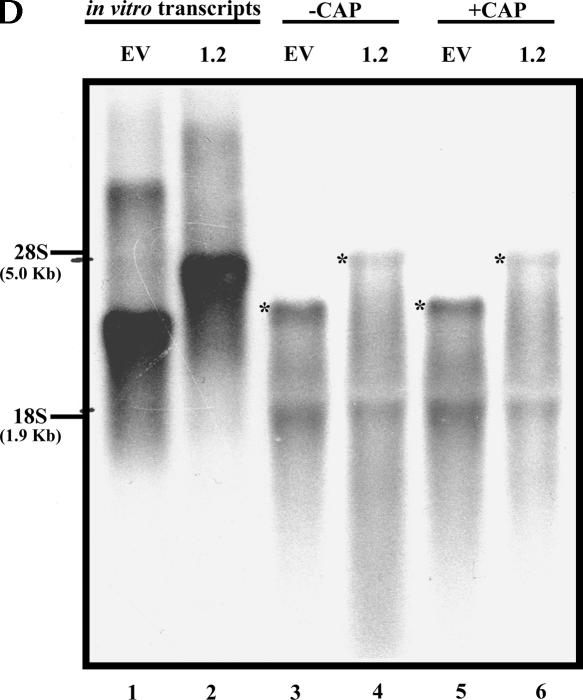

FIGURE 4.

The LEF1 5′-UTR exhibits bona fide IRES activity in the cytoplasm. (A) The dicistronic plasmids were transcribed in vitro, and mRNAs were transiently transfected into COS-1 cells. A dual luciferase reporter assay was performed 20–24 h post-transfection to examine IRES activity. The ratio of FLuc:RLuc was calculated. y-axis (logarithmic scale): The fold elevation over empty vector set equal to 1. (B) Uncapped and capped dicistronic mRNAs transcribed in vitro were transiently transfected into COS-1 cells, and RLuc and FLuc activities were measured as described above. y-axis: Relative light units (RLUs) generated in logarithmic scale. (C) COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with capped dicistronic mRNAs +/− an mRNA synthesized from a plasmid (pT7PV1-ΔNS) containing the entire poliovirus genome (excluding sequences encoding most of the structural proteins) to express PV2A proteinase (Ypma-Wong and Semler 1987). A dual luciferase reporter assay was performed as described above. y-axis: RLUs generated by Renilla (top panel) and Firefly (bottom panel) Luciferase in logarithmic scale. These graphs contain results from one of three representative experiments. (D) 3.0 μg of total RNA from COS-1 cells transiently transfected with (uncapped or capped) dicistronic mRNAs 6-h post-transfection was analyzed by Northern blot. Dicistronic mRNAs were detected using a random prime [32P]-labeled probe against FLuc coding region sequences and are denoted by “*”. “EV”, the empty vector, pRSTF, with no insert; “1.2”, pRSTF with the LEF1 1.2-kb 5′-UTR. The in vitro synthesized (uncapped) dicistronic transcripts were loaded in lanes 1 and 2. Migration of the 28S and 18S ribosomal RNAs is indicated.

When introduced directly into the cytoplasm, the LEF1 5′-UTR mediated significant levels of FLuc expression. As shown in Figure 4A, the FLuc:RLuc ratio was 30-fold greater than that of the empty vector. This result is in very good agreement with the corresponding DNA transfection in which the LEF1 IRES was 60 times more active than the empty vector. The lower activity in the RNA transfections suggests that nuclear factors may be required for maximal IRES activity (Stoneley et al. 2000; Shiroki et al. 2002). The Kv1.4 IRES demonstrated relatively weak activity (sevenfold) equivalent to that observed in DNA transfections (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the IRES of CVB3 was highly active, 487 times more active than the empty vector. In the DNA transfection, the IRES activity of CVB3 was lower than that of LEF1 (29-fold compared to 60-fold). Coxsackievirus is a picornavirus with a purely cytoplasmic replication cycle, and its RNA does not need to cycle through the nucleus for any events such as replication or translation; therefore, the extremely high activity of this viral IRES in the RNA transfections could be due to the lack of a requirement for nuclear factors.

The LEF1 IRES is insensitive to a cap structure

A defining feature of IRES activity is the ability to promote translation in the absence of a 5′-cap structure. Although a cap did not enhance translation of the LEF1 mRNA in vitro (Fig. 1C), we wanted to examine whether the dicistronic LEF1 mRNA is influenced by a cap structure. Thus capped and uncapped dicistronic transcripts were transiently transfected in parallel into COS-1 cells. Figure 4B shows that all uncapped mRNAs generated ~9000 relative light units (RLUs) of RLuc (black bars), the upstream cistron which relies on cap-dependent translation. Capping these transcripts resulted in more efficient cap-dependent translation of RLuc by three orders of magnitude (~9 million RLUs, dark gray bars). Clearly, the presence of a 5′-cap greatly enhanced translation and efficiency of ribosome scanning of the first cistron. In addition, capping the empty vector resulted in a > 20-fold increase in FLuc activity from 300 RLUs with uncapped message to 7000 RLUs with capped message. We interpret this result to mean that even though this vector contains a hairpin structure in the intercistronic region, it does not completely prevent ribosomal read-through or reinitiation in the absence of an insert or in the presence of a very short insert. In contrast, the long 5′-UTR of LEF1 was insensitive to a cap structure, as it demonstrated equal activity in the presence and absence of a cap (~7000 RLUs). As expected, the high level of CVB3 IRES activity was also cap-insensitive. These data are consistent with the apparent cap-independence observed in our in vitro experiments with rabbit reticulocyte lysates. However, because the read-through levels of FLuc with the capped empty vector were similar to the levels of FLuc generated from uncapped LEF1 message, we wanted to further assess cap-dependent translation via the LEF1 5′-UTR. As a test, we sought to down-regulate cap binding activity in cells by expressing the poliovirus proteinase 2A (PV2A).

The LEF1 5′-UTR supports translation of the cap-independent cistron when cap-dependent translation is suppressed

To disrupt the cap binding protein complex, PV2A was co-expressed with the dicistronic transcripts. PV2A is a proteinase that cleaves eIF4G (a subunit of the cap binding complex) and uncouples the cap recognition and helicase functions of the cap binding complex (Kuechler et al. 2002; Zamora et al. 2002). To express PV2A, a plasmid that contains the entire poliovirus genome (excluding the sequences necessary to produce structural proteins) was utilized (Ypma-Wong and Semler 1987). The modified genome was transcribed in vitro, and the RNA was cotransfected with capped dicistronic mRNAs into COS-1 cells. Figure 4C shows that co-expression of PV2A decreased RLuc activity greater than twofold; therefore, cap-dependent translation was compromised in these cells by at least 50%. Importantly, co-expression of PV2A resulted in a significant decrease in the FLuc activity generated by the empty vector. This supports the proposition that FLuc expression from the uncapped empty vector transcript is due to reinitiation and scanning of ribosomes. In contrast, FLuc expression mediated by the LEF1 IRES was insensitive to suppression of cap-dependent translation, as the FLuc signal generated was not significantly different from that detected in the uncompromised cells; this supports our conclusion that there is little or no reinitiation of ribosomes from the upstream, cap-dependent cistron. Thus, even though the FLuc levels generated from capped empty vector message and capped LEF1 UTR message are similar, translation proceeds by two very different mechanisms. As expected, the IRES activity of CVB3 was greatly enhanced upon co-expression of PV2A (Pelletier and Sonenberg 1988). To analyze RNA integrity, the in vitro synthesized (uncapped and capped) dicistronic transcripts, pRSTF and pRSTF-LEF(1.2), were transfected into COS-1 cells and detected 6 h post-transfection by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 4D). Although there is RNA degradation, there is no evidence of cleaved products that may contribute to FLuc expression. A smaller species is present in all of the lanes but appears to be due to background binding of the probe to the 18S rRNA and most likely does not represent a monocistronic transcript. Jang et al. (2004) showed that levels of RNA decrease over time (5 h and 15 h post-transfection); however, addition of a cap structure does not contribute to RNA stability, and IRES activity is no different when assayed 6 and 16 h post-transfection (data not shown). Taken together, the results from the DNA and RNA transfections show that the LEF1 5′-UTR contains an authentic IRES element.

Mapping the LEF1 IRES

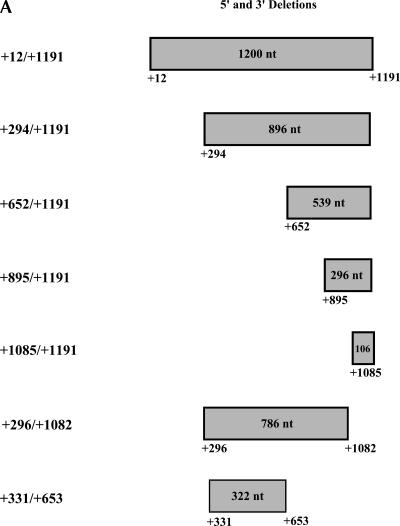

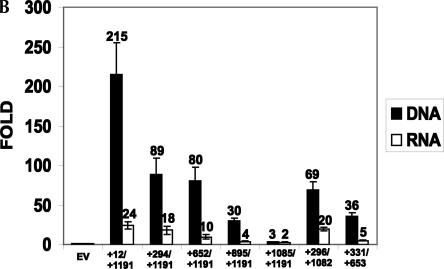

To delimit the minimal sequences necessary for IRES activity, nested deletions from the 5′-end of the UTR to +294 (+294/+1191), +652 (+652/+1191), +895 (+895/+1191), and +1085 (+1085/+1191) were cloned into the dicistronic vector and are depicted in Figure 5A. These 5′-deletion constructs were then transfected as DNA or in vitro synthesized mRNA transcripts into COS-1 cells, and their respective luciferase activities were assayed.

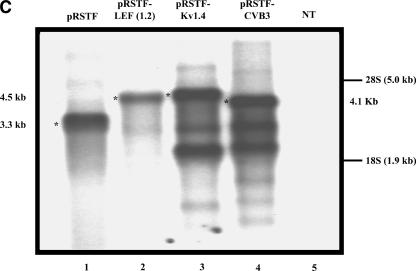

FIGURE 5.

Mapping the LEF1 IRES. (A) Schematic representation of the 5′ and 3′ deleted regions of the LEF1 5′-UTR generated to delimit the IRES. 1.2 kb (+12/+1191), 896 nt (+294 /+1191), 539 nt (+652/+1191), 296 nt (+895/+1191), 106 nt (+1085/+1191), 786 nt (+296/+1082), and 322 nt (+331/+653) of the LEF1 5′-UTR were subcloned into pRSTF as detailed in Materials and Methods. (B) The dicistronic LEF1 5′ and 3′ deletion constructs (open bars) or in vitro synthesized dicistronic mRNAs (black bars) were transiently transfected into COS-1 cells, and a dual luciferase reporter assay was performed to measure RLuc and FLuc activities 6 h post-transfection. IRES activity was calculated as the ratio of FLuc:RLuc. y-axis: The fold elevation over empty vector. RLuc RLUs were relatively equal for all of the deletion constructs as well as the empty vector in both DNA and RNA transient transfections; therefore, the FLuc:RLuc ratios are not artificially elevated.

Overall, concordant patterns of activity were observed for the DNA and RNA transfections (Fig. 5B). IRES activity decreases 2.4-fold/1.3-fold (DNA/RNA) when 294 nt are deleted from the 5′-end of the UTR (+294/+1191). Further deletion to +652 and +895 resulted in an overall drop of 2.7-fold/2.4-fold and 7.2-fold/6.0-fold, respectively compared to the full-length UTR. Nearly all IRES activity was eliminated by deletion to +1085 (threefold/twofold activity relative to the empty vector, 72-fold/12-fold less active than the full-length 1.2-kb 5′-UTR). It is important to note that while FLuc activity decreased with successive 5′-deletions, the RLuc activity remained constant for each construct, arguing against ribosomal reinitiation (data not shown). If FLuc expression was due to read-through from the upstream cistron, we would expect the dicistronic vector containing the shorter regions of the LEF1 5′-UTR to demonstrate a gradual increase in FLuc activity.

To establish a 3′-border, deletions from the 3′-end of the active, central UTR (+294/+1191) were tested in the dicistronic vector: +296/+1082 and +331/+653 (Fig. 5A). As for the 5′-deletions, DNA- and RNA-based transfections yielded similar trends (Fig. 5B). That is, deletion of the 3′ 109 nt resulted in very little change in IRES activity (cf. +294/+1191 and +296/+1082) in either type of transfection, whereas a 2.5-fold/3.6-fold (DNA/RNA) decrease in IRES activity was observed when 538 nt (+331/+653) were removed from the 3′-end of the active central region. Compared to the full-length UTR, this latter fragment is 6.0-fold/4.8-fold (DNA/RNA) less active.

It appears that no single region carries full IRES activity, although the region between +652 and +1085 may be particularly important as its removal causes the largest decrease (cf. +652/+1191 with +895/+1191, and +296/+1082 with +331/+653). Instead, the 5′-UTR can be divided into subfragments that carry significant, independent IRES activity. For example, activity can be detected within the proximal 592 and distal 322 nt, but IRES activity increases in an additive fashion when these regions are present together in a single fragment (+294/+1191). Furthermore, overall activity is maximal when the entire UTR sequence is included. This progressive rather than abrupt loss of activity is consistent with the idea that cellular IRES elements are modular in nature, and that these modules cooperate to direct efficient internal initiation (Jang et al. 2004; Jopling et al. 2004).

DISCUSSION

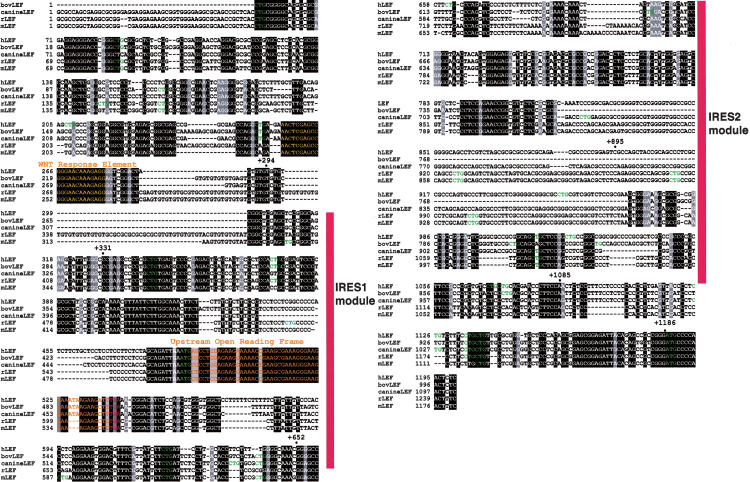

We demonstrate that the 5′-UTR of LEF1 mRNA mediates internal ribosome entry for translation of full-length LEF-1 protein. DNA and RNA transfections of a dicistronic vector containing the 1.2-kb 5′-UTR revealed that LEF1 mRNA exhibits strong IRES activity via the cooperation of at least two independent modules. In the course of our studies, we found that the LEF1 5′-UTR contains a Pol II promoter (Promoter 3) that generates an ~3.0-kb LEF1 message (data not shown). Based on the location of the promoter relative to the IRES modules, the predicted 3.0-kb message should produce protein via IRES(es). Thus, all messages that encode full-length, oncogenic LEF-1 protein are translated by internal ribosome entry. Northern blot analysis as well as transient DNA transfections of a promoter-less dicistronic vector containing the LEF1 5′-UTR demonstrated that Promoter 3 does not significantly contribute to FLuc expression in the reporter assays (Fig. 3). To further address the possible expression of monocistronic FLuc mRNAs, we directly transfected dicistronic mRNAs into COS-1 cells (Fig. 4). These experiments showed that the LEF1 5′-UTR can mediate translation when introduced directly into the cytoplasm, even under conditions where cap-dependent translation is suppressed; however, translation is not as efficient as that detected in the corresponding DNA transfections (cf. COS-1 transfections in Fig. 2B and Fig. 4A; see Fig. 5B). The lower IRES activity of the transfected RNA suggests that some nuclear event and/or factors are required for maximal IRES activity. Similar conclusions have been drawn for c-Myc and Smad 5 IRES-containing mRNAs (Stoneley et al. 2000; Shiroki et al. 2002); however, this may not hold true for all cellular IRES elements since Kv1.4 IRES activity was the same in the DNA and RNA transfections. In contrast, the activity of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) IRES was greatly enhanced when directly introduced into the cytoplasm rather than cycling through the nucleus in the DNA transient transfections. Optimal expression of the viral IRES in the cytoplasm-only experiment is consistent with what is known about picornavirus replication occurring exclusively in this cellular compartment (Fig. 4A; Racaniello 2001). Progressive removal of sequences from the 5′- and 3′-ends of the LEF1 5′-UTR reduces, but does not abrogate, IRES activity (Fig. 5), consistent with the idea that cellular IRES elements require multiple RNA components for efficient activity. Indeed, nucleotide alignment of the human, bovine, canine, mouse, and rat LEF1 genes shows that the 5′-UTR is very well conserved in distinct regions or motifs (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

The LEF1 5′-UTR is evolutionarily conserved. Nucleotide alignment of the 5′-UTRs of the human, bovine, canine, rat, and mouse LEF1 genes. The P1 transcription start site as well as the WNT response element, the upstream open reading frame (uORF), upstream CUGs, and the authentic translation start site are indicated (in green). In addition, positions of the deletion fragments relative to the Promoter 1 transcription start site are indicated. Shaded areas represent conserved regions, and the two IRES modules are highlighted by the red bars.

In Figure 6A, the highly conserved WNT response elements downstream of Promoter 1 are indicated, as are the upstream AUGs and CUGs (Hovanes et al. 2001; Atcha et al. 2003). These WNT response elements activate Promoter 1 transcription as well as transcription of the weaker, internal Promoter 3 (data not shown; Atcha et al. 2003). A variable (UG)n repetitive sequence separates these promoter regulatory elements from the remainder of the 5′-UTR. Interestingly, in transient DNA transfections, removal of the first 294 nt of the 5′-UTR up to this repetitive sequence causes a significant decrease in IRES activity (215-fold down to 89-fold above empty vector); however, this was not recapitulated in the RNA transfections (24-fold vs. 18-fold above empty vector), suggesting that elements contributing to IRES activity are located downstream and that the (UG)n sequence may demarcate a boundary within the UTR. A major difference between the DNA and RNA transfections is that in the DNA transfections, the dicistronic mRNA is authentically generated in the nucleus as opposed to introduction of synthetically generated RNA into the cytoplasm via RNA transfection. It is possible that transcription of the dicistronic mRNA in the nucleus and its proper export to the cytoplasm may enable the loading of additional factors to sequences between +1 and +300 that positively enhance translation by ribosomes. We conclude that the first 294 nt are unlikely to carry an independent IRES module because of its modest contribution in the RNA transfections.

Based on our deletion analysis and the nucleotide alignment, it appears that the LEF1 5′-UTR contains at least two independent IRES modules that are additive at the RNA level. The +296/+1082 fragment is the shortest fragment that carries most of the IRES activity in the RNA transfections (20-fold over empty vector vs. 24-fold for the intact UTR). Data in Figure 5B show that within this fragment, two independent IRES modules can be delimited to +331/+653 and +652/+1085.

The first IRES module (+331/+653) independently demonstrates 36-fold/5-fold (DNA/RNA) activity relative to the empty vector. Removal of these sequences from the full-length UTR results in a 2.7-fold/2.4-fold decrease in IRES activity. The nucleotide alignment also reveals two very well conserved regions within +331/+653. The most remarkable conservation is an absolutely conserved AUG and small uORF. This AUG is the only upstream translation start codon in any frame of any of the orthologous UTRs— suggesting that other AUGs may be deleterious to authentic translation. Small uORFs present in 5′-leaders have been shown to promote as well as inhibit downstream initiation of translation (Geballe and Morris 1994). Yaman et al. (2003) demonstrated that translation of a small uORF in the leader of the cat-1 mRNA results in a conformational change that yields an active IRES—a “zipper” mechanism. Indeed, activity decreases by 2.4-fold (RNA transfection) when the 5′-UTR is truncated to +652/+1191 and does not include this uORF. We tested the possibility that active translation of the uORF affects LEF1 translation by deleting the AUG or altering the frame of the coding sequence. Neither mutation had any effect on IRES activity or translation of LEF-1 in COS-1 cells (data not shown). Structures predicted by mfold show a Y-stem loop built, in part, by the highly conserved uORF (data not shown). This structure is preserved when the entire 1.2-kb sequence as well as a subregion (+294 to +652) of the sequence are submitted to mfold. Indeed, in silico folding of the corresponding mouse and rat sequences also yields a similar Y structure even though the position of uORF relative to the stem is not conserved. Because our experiments do not reveal a need for active translation of the uORF (mutation of the AUG codon has no effect on translation of the downstream ORF) and since folding of analogous mouse and rat LEF1 5′-UTR sequences reveals a conserved Y-structure that is composed of sequences immediately downstream of their respective uORFs, we hypothesize that the putative Y-structure is more important for IRES activity than translation of the uORF. A role for the uORF in regulation of LEF-1 translation may occur under physiological conditions that are not replicated in our experimental systems.

The second module (+652/+1085) appears to carry greater activity than the first IRES module, as its deletion causes the largest drop in IRES activity within various subfragments (cf. +296/+1082 with +331/+653, and +652/+1191 with +1085/+1191). This module contains two separate blocks of sequence homology among the orthologs: the first spanning from ~+658 to +814 and the second starting at ~+969 to +1085. The intervening, less-well-conserved sequence is completely missing in the bovine ortholog and is not well conserved among the rest of the orthologs. Even within this second subregion there is variable spacing between small but highly conserved blocks of nucleotide motifs. Either small sequence motifs contribute to IRES-mediated translation, or secondary and tertiary structures are highly conserved despite major differences in spacing among the small motifs. Other highly conserved sequences occur just upstream of the authentic LEF-1 coding sequence, and although mfold predicted structures reveal a conserved stem loop within the last 100 nt of the UTR (data not shown), these sequences are not likely to be involved in IRES activity since their removal does not have a significant effect (+296/+1082 fragment demonstrated relatively equal activity to that of +294/+1191). Clearly, extensive mutational analysis of these conserved sequence motifs and putative structures will enable better definition of the features that contribute to IRES activity.

The question arises as to why LEF1 mRNA utilizes a noncanonical translation mechanism. The two LEF1 mRNA species that encode full-length activating LEF-1 (3.6 kb and the minor 3.0 kb) are expressed in colon cancer, while the message that encodes the truncated LEF-1 isoform that might function as a tumor suppressor is not expressed. This latter message contains a 60-nt 5′-UTR and likely utilizes the conventional cap-dependent scanning mechanism to initiate protein synthesis. The 1.2-kb 5′-UTR may impose an additional level of regulation on the expression of full-length, growth-promoting LEF-1 protein, leaving the smaller truncated form of LEF-1 to be produced via conventional, efficient translation pathways. Indeed, the full-length LEF-1 open reading frame begins with a suboptimal match (GGGAUGC) to the consensus context of translation start codons, whereas the truncated LEF-1 open reading frame begins with a sequence that is optimal (AUAAUGA) (Kozak 1981). Taken together, these features suggest that full-length LEF1 mRNAs are not translated efficiently and are likely to be subject to more regulation compared to truncated LEF1 mRNAs.

As for in vivo evidence that LEF-1 protein production is regulated, Fuchs and colleagues have noted that the expression of LEF1 mRNA does not fully correlate with LEF-1 protein in hair follicles. The mRNA is highly expressed in the mitotically active matrix cells of the developing hair follicle, but LEF-1 protein expression and WNT signaling activity is only observed in the post-mitotic, differentiating precortex cells (DasGupta and Fuchs 1999). Some cellular IRES-containing mRNAs have been shown to be regulated during the cell cycle or differentiation in ways that differ from the activities of cap-dependent translation (Bernstein et al. 1995; Pyronnet et al. 2000). We note that production of full-length LEF-1 is likely to be insensitive to regulatory changes in cap-dependent translation, unlike its truncated counterpart, since suppression of cap-dependent translation via co-expression of poliovirus 2A proteinase did not affect LEF1 5′UTR-mediated translation (Fig. 4C). This suggests that LEF1 has evolved a mechanism to initiate protein synthesis of its growth-promoting isoform under conditions where cap-dependent translation may be compromised, such as during cell division or stress. LEF-1 is produced in rapidly dividing, undifferentiated cells, and therefore this may be an important aspect to its translation. Furthermore, LEF-1 is also produced in many different types of cancers where cells are rapidly proliferating and may be under genotoxic and or hypoxic stress. Full-length LEF-1 protein production during these various circumstances of cellular stress may remain constant when controlled by IRES elements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid design

LEF-1 ORF constructs

The LEF-1 ORF, including the entire 1.2-kb 5′-UTR as well as 1.2 kb of the 3′-UTR, was subcloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pCS2, which was digested with BamHI and SnaBI in the polylinker region followed by incubation with Klenow to produce blunt ends. N-terminal deletions of the 5′-UTR (−957 and −654) were created by replacing the full-length UTR with partial UTR sequences from isolated human cDNA clones using the BamHI site in the pCS2 vector and the Not I site in the UTR near the authentic AUG codon (K. Hovanes, unpubl.). The expression vector missing all the LEF1 5′-UTR sequences was created by insertion of the following annealed sense/antisense oligonucleotides into BamHI (pCS2) and BspEI (LEF-1 ORF) sites:

sense: 5′-GATCCTACGTAGGGATGCCCCAACTCT-3′, and

antisense: 5′-CCGGAGAGTTGGGGCATCCCTACGTAG-3′.

Dual luciferase dicistronic constructs

Oligonucleotide pairs were designed and used to amplify 1.178 Kb (+12 to +1191 relative to the P1 transcription start site), 896 (+294 to +1191), 539 (+652 to +1191), 296 (+895 to +1191), 106 (+1085 to +1191), and 786 (+296 to +1082) bp of the LEF1 5′-UTR via PCR methods using the genomic 5Ba clone (Hovanes et al. 2000) as the DNA template and the Deep VentR DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs). The PCR products were verified by analysis on agarose gels, gel purified, and subsequently phosphorylated with T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (New England Biolabs). The LEF1 5′-UTR fragments were then ligated into the dicistronic vector, pRSTF (Jang et al. 2004) at an AfeI site in the multiple cloning region. The fragments were ligated into the vector using T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen) and transformed into competent DH5α bacteria. Plasmid constructs were verified by restriction digest and sequence analysis. The following oligonucleotides were utilized to create the respective regions of the LEF1 5′-UTR:

5b 685-sense: 5′-GCGCGGGAGGAGGAGAAGCAGTGG-3′ (1.178 kb);

5b 967-sense: 5′-TGTGTCGGCTCGAGCTCCGGG-3′ (896 bp);

5b1324-sense: 5′-GGGGCCCTTCTGCCCAGATCC-3′ (539 bp);

5b1564-sense: 5′-AGTCGCCAGCTACCGCAGCCC-3′ (296 bp);

5b1756-sense: 5′-TTCCAACTCTCCTTTCCTCCCCCACCC-3′ (106 bp);

5b1863-antisense: 5′-GGGCATCCCGGCGGCTCTGTAATC-3′;

5b 967-sense: 5′-TGTGTCGGCTCGAGCTCCGGG-3′ (786 bp); and

5b1755-antisense: 5′-GGGTTCGTGCAGCAGGACAGCCCCTACGGG-3′.

The genomic 5ba clone (Hovanes et al. 2000) was digested with ApaI, and the resulting 322-bp (+331/+653) fragment was subjected to incubation with Klenow to generate blunt ends and subcloned into the dicistronic vector, pRSTF, as described above.

The dicistronic constructs pRSTF-Kv1.4 and pRSTF-CVB3 are described in (Jang et al. 2004).

Promoter-less dicistronic constructs

The dicistronic vector lacking the SV40 promoter, the chimeric intron, and the T7 promoter as well as the constructs pRSTFΔSV40-Kv1.4 and pRSTFΔSV40-CVB3 are as described by Jang et al. (2004); 1.178 Kb of the LEF1 5′-UTR was PCR-amplified using the primer pair 5b 685-S and 5b1863-AS and ligated into pRSTFΔSV40 as described above for the intact dicistronic constructs.

In vitro transcription

The LEF-1 ORF mRNAs used in the in vitro translation reactions were generated by in vitro transcription of the pCS2 plasmids linearized with XmnI using the SP6-based Megascript in vitro transcription kit (Ambion). The linearized plasmids were subjected to phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. In vitro transcription reactions were performed using 1.0 μg of linearized template and incubated at 37°C for 2–4 h in the presence or absence of cap analog (Ambion). The reactions were subsequently treated with DNase I at 37°C for 15 min, subjected to phenol/chloroform extraction, and followed by chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation. The transcripts were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. The dicistronic constructs and pT7PV1ΔNS were digested with Pme I and Pvu I, respectively, and subjected to phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The linearized plasmids were transcribed in vitro using the T7-based Megascript in vitro transcription kit (Ambion) in the presence or absence of cap analog (Ambion). The reactions were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the integrity of the transcripts was verified as described above.

In vitro translation

Translation experiments in the rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) were carried out using 250 ng of capped or uncapped LEF-1 ORF in vitro transcription products. The reactions (50 μL) contained 50% concentrated rabbit reticulocyte lysate and [35S]-methionine (1175 Ci/mMol). The reactions were incubated at 30°C for 90 min, and the translation products (2 μL or 4%) were resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing SDS. The gel was incubated in Enhance (Fisher Scientific) solution for 30 min, rinsed with ddH2O, dried and exposed to film and phosphorimager screens. Quantity One software was utilized to quantitate bands.

Cell culture

HeLa(S), SW480 C7, and COS-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% 2 mM glutamine. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. All cell culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen.

Transient transfections

Cells were seeded 16–24 h prior to transfection, generating monolayers 50%–80% confluent. Six-well plates and 10-cm dishes were used for luciferase reporter assays and total RNA isolation, respectively.

For total RNA isolation, cells were seeded 24 h before transfection on 10-cm plates, generating monolayers ~80% confluent. For RNA isolation from HeLa cells, 2.0 μg of each dicistronic plasmid was transfected using the Effectene transfection reagent (QIAGEN) at a ratio of 1:10 (1 μg plasmid DNA: 10 μL of Effectene reagent) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The transfections were performed in triplicate and pooled for total RNA isolation 24 h post-transfection. For COS-1 cells, 3.0 μg of each dicistronic plasmid was transfected into each 10-cm dish using the FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at a ratio of 1:3 (1 μg of plasmid DNA: 3 μL of FuGENE reagent). Transfections were performed in duplicate and pooled for total RNA isolation 24 h later.

For DNA transient transfections, 1.0 μg of each dicistronic construct was transfected into cells using the FuGENE transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In transient transfections of the promoter-less dicistronic plasmids, 0.1 μg of a CMV β-Galactosidase reporter plasmid was cotransfected to serve as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Monolayers were incubated with transfection complexes for 20–24 h and subsequently harvested for dual luciferase assays.

For RNA transient transfections, ~2.0 μg of capped or uncapped in vitro transcribed RNA was transfected per well using the Transmessenger transfection kit (QIAGEN). A ratio of 1:6 (1 μg of plasmid DNA: 6 μL of transmessenger reagent) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To express PV2A proteinase, ~1.0 μg of in vitro transcribed pT7PV1ΔNS RNA (Ypma-Wong and Semler 1987) or 1.0 μg of yeast tRNA was cotransfected with 2.0 μg of the dicistronic mRNAs. Monolayers were incubated with transfection complexes for 1–3 h at 37°C, rinsed with 1X PBS-EDTA, and subsequently incubated at 37°C in serum-containing media (DMEM). Cells were harvested and assayed for luciferase activities 6 or 21 h post-transfection. All transfections were performed in duplicate and carried out at least three times in all cell lines.

Dual luciferase and β-galactosidase assays

Monolayers were washed with 1× Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS)-EDTA and lysed with 1× Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) 6–21 h or 24 h post-RNA or DNA transfection, respectively. Cell lysates were subjected to one freeze/thaw cycle in dry ice and 37°C, respectively and assayed for luciferase activities using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Assays were performed using a Monolight 2010 luminometer (Analytical Luminesence Laboratory) or a SIRIUS luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems). FLuc/RLuc ratios were calculated for each sample, and the average value is represented as fold elevation over background, which is expression measured from the vector in the absence of an insert. β—Galactosidase activity was determined using the Galacton-Plus substrate (Applied Biosystems) to normalize luciferase activity for each point.

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis

Cytoplasmic RNA was isolated from cells using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Poly(A) RNAs were then isolated from 250 μg of total RNAs isolated from COS-1 cells using the Oligotex mRNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN). The Poly(A) Pure mRNA Purification Kit was used to isolate mRNA from total RNA (500–1000 μg) isolated from HeLa cells; 4.0 μg of Poly(A) RNA was denatured in RNA sample cocktail (formamide, formaldehyde, and 5X formaldehyde running buffer) at 65°C for 15 min and resolved on a 1.0% formaldehyde (37%) agarose gel with continuous buffer circulation at 5 V/cm (100 V) for 6.5 h. RNA was transferred to a Hybond-N (Amersham) membrane by upward capillary transfer with 10×SSC for 8–10 h. Following transfer, membranes were briefly rinsed with ddH2O, UV-irradiated, and soaked in 5% acetic acid for 10 min, soaked in 0.04% methylene blue dye (in 0.5M NaOAc) for 10 min, and rinsed with ddH2O to visualize the ribosomal 28S and 18S RNAs. Membranes were then prehybridized at 60° in ExpressHyb Hybridization Solution (BD Biosciences) for 3–4 h in a hybridization chamber. The membranes were then hybridized in fresh hybridization solution with random prime [32P]-labeled probes (1 × 106 cpm/mL) against the Firefly Luciferase (FLuc) coding region sequence at 60°C, overnight. Following hybridization, membranes were initially washed twice with 1×SSC/0.1% SDS at room temperature and subsequently washed in 1×SSC/0.1% SDS at 60°C for 15 min and exposed to film and/or phosphorimager screens. The FLuc probe was generated via PCR using oligonucleotides specific to 500 bp of FLuc-specific coding region sequence using the plasmid pRSTF as the DNA template. The 500-bp PCR product was labeled using the MegaPrime DNA Labeling System (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Autoradiography of the membranes was performed overnight at −80°C. A phosphorimager with Quantity One version 4.3.0 (Biorad) was used to visualize the bands.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristin M. Bedard for her experimental advice with in vitro transcription and translation experiments, Sharlene R. Lim for her help using Quantity One software, and Dr. Klemens Hertel for careful reading and critique of the manuscript. We are also grateful to all members of the Waterman, Semler, and Hertel laboratories for their technical advice and useful discussions.

This work was funded by NIH CA83982 and CA096878 to M.L.W. and by NIH AI26765 to B.L.S. J.J. is supported by the MARC (Minority Access to Research Careers) pre-doctoral fellowship (GM067285-02) from the NIH/NIGMS (National Institute of General Medical Sciences), and G.M.J. was a post-doctoral trainee of Public Health Service training grant GM07311.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.7226105.

REFERENCES

- Aoki, M., Hecht, A., Kruse, U., Kemler, R., and Vogt, P.K. 1999. Nuclear endpoint of Wnt signaling: Neoplastic transformation induced by transactivating lymphoid-enhancing factor 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 139–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atcha, F.A., Munguia, J.E., Hovanes, K., Li, T.W.H., and Waterman, M.L. 2003. A new β-catenin dependent activation domain in T cell factor. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 16169–16175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J., Shefler, I., and Elroy-Stein, O. 1995. The translational repression mediated by the platelet-derived growth factor 2/c-sis mRNA leader is relieved during megakaryocytic differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 10559–10565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz, M. and Clevers, H. 2000. Linking colorectal cancer to Wnt signaling. Cell 103: 311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, S.A., Edelman, G.M., and Mauro, V.P. 2000. A9-nt segment of a cellular mRNA can function as an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and when present in linked multiple copies greatly enhances IRES activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 1536–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, S.A., Owens, G.C., and Mauro, V.P. 2001. A 5′ leader of Rbm3, a cold stress-induced mRNA, mediates internal initiation of translation with increased efficiency under conditions of mild hypothermia. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 36917–36922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta, R. and Fuchs, E. 1999. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development 126: 4557–4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filali, M., Cheng, N., Abbot, D., Leontiev, V., and Engelhardt, J.F. 2002. Wnt-3A/β-catenin signaling induces transcription from the LEF1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 33398–33410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geballe, A. and Morris, D. 1994. Initiation codons within 5′ leaders of mRNAs as regulators of translation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19: 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellen, C. and Sarnow, P. 2001. Internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNA molecules. Genes & Dev. 15: 1593–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovanes, K., Li, T.W.H., and Waterman, M.L. 2000. The human LEF-1 gene contains a promoter preferentially active in lymphocytes and encodes multiple isoforms derived from alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 1994–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovanes, K., Li, T.W.H., Munguia, J.E., Troung, T., Milovanovic, T., Marsh, J.L., Holcombe, R.F., and Waterman, M.L. 2001. β catenin sensitive isoforms of Lymphoid Enhancer Factor-1 are selectively expressed in colon cancer. Nat. Genet. 28: 53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huez, I., Creancier, L., Audigier, S., Gensac, M.C., Prats, A.C., and Prats, H. 1998. Two independent internal ribosome entry sites are involved in translation initiation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 6178–6190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.K., Krausslich, H.G., Nicklin, M.J., Duke, G.M., Palmenberg, A.C., and Wimmer, E. 1988. A segment of the 5′ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J. Virol. 62: 2636–2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang, G.M., Leong, L.E.-C., Hoang, L.T., Wang, P.H., Gutman, G.A., and Semler, B.L. 2004. Structurally distinct elements mediate internal ribosome entry within the 5′ noncoding region of a voltage-gated potassium channel mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 47419–47430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling, C.L., Spriggs, K.A., Mitchell, S.A., Stoneley, M., and Willis, A.E. 2004. L-Myc protein synthesis is initiated by internal ribosome entry. RNA 10: 287–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. 1981. Possible role of flanking nucleotides in recognition of the AUG initiator codon by eukaryotic ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 9: 5233–5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002. Pushing the limits of the scanning mechanism for initiation of translation. Gene 299: 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2003. Alternative ways to think about mRNA sequences and proteins that appear to promote internal initiation of translation. Gene 318: 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuechler, E., Seipelt, J., Liebig, H.D., and Sommergruber, W. 2002. Picornavirus proteinase-mediated shutoff of host cell translation: Direct cleavage of a cellular initiation factor. In Molecular biology of picornaviruses (eds. B.L. Semler and E. Wimmer), pp. 301–311. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Martinez-Salas, E., Lopez de Quinto, S., Ramos, R., and Fernandez-Miragall, O. 2002. IRES elements: Features of the RNA structure contributing to their activity. Biochimie 84: 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, J. and Sonenberg, N. 1988. Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature 334: 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, J., Kaplan, G., Racaniello, V.R., and Sonenberg, N. 1988. Cap-independent translation of poliovirus mRNA is conferred by sequence elements within the 5′ noncoding region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8: 1103–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polakis, P. 2000. Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes & Dev. 14: 1837–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyronnet, S., Pradayrol, L., and Sonenberg, N. 2000. A cell cycle-dependent internal ribosome entry site. Mol. Cell 5: 607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X. and Sarnow, P. 2004. Preferential translation of internal ribosome entry site-containing mRNAs during the mitotic cycle in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 13721–13728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racaniello, V.R. 2001. Picornaviridae: The viruses and their replication. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- Reya, T., O’Riordan, M., Okamura, R., Devaney, E., Willert, K., Nusse, R., and Grosschedl, R. 2000. Wnt signaling regulates B lymphocyte proliferation through a LEF-1 dependent mechanism. Immunity 13: 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev, S., Bruhn, L., Sieber, H., Pichler, A., Melchior, F., and Grosschedl, R. 2001. PIASy, a nuclear matrix-associated SUMO E3 ligase, represses LEF1 activity by sequestration into nuclear bodies. Genes & Dev. 15: 3088–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroki, K., Ohsawa, C., Sugi, N., Wakiyama, M., Miura, K., Watanabe, M., Suzuki, Y., and Sugano, S. 2002. Internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation of Smad5 in vivo: Requirement for a nuclear event. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 2851–2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg, N. and Pyronnet, S. 2001. Cell-cycle-dependent translational control. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11: 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneley, M., Paulin, F.E.M., Le Quesne, J.P.C., Chappell, S.A., and Willis, A.E. 1998. C-myc 5′ untranslated region contains an internal ribosome entry segment. Oncogene 16: 423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneley, M., Subkhankulova, T., Le Quesne, J.P.C., Coldwell, M.J., Jopling, C.L., Belsham, G.J., and Willis, A.E. 2000. Analysis of the c-myc IRES; a potential role for cell-type specific trans-acting factors and the nuclear compartment. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 687–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkin, Y.V., Ovchinnikov, L.P., Dreyfuss, G., and Sonenberg, N. 1996. General RNA binding proteins render translation cap dependent. EMBO J. 15: 7147–7155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagner, S., Galy, B., and Pyronnet, S. 2001. Irresistible IRES. Attracting the translation machinery to internal ribosome entry sites. EMBO Rep. 2: 893–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eden, M.E., Byrd, M.P., Sherrill, K.W., and Lloyd, R.E. 2004. Demonstrating internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNAs using stringent RNA test procedures. RNA 10: 720–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis, A. 1991. Translational control of growth factor and proto-oncogene expression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31: 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, I., Fernandez, J., Liu, H., Caprara, M., Komar, A.A., Koromilas, A.E., Zhou, L., Snider, M.D., Scheuner, D., Kaufman, R.J., et al. 2003. The zipper model of translational control. A small upstream ORF is the switch that controls structural remodeling of an mRNA leader. Cell 113: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ypma-Wong, M.F. and Semler, B.L. 1987. Processing determinants required for in vitro cleavage of the poliovirus P1 precursor to capsid proteins. J. Virol. 61: 3181–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora, M., Marissen, W.E., and Lloyd, R.E. 2002. Poliovirus-mediated shutoff of host translation: An indirect effect. In Molecular biology of picornaviruses (ed. B.L. Semler and E. Wimmer), pp. 313–320. ASM Press, Washington, DC.