Abstract

Molecular engineering has led to the development of a novel target-dependent riboswitch that increases δribozyme fidelity. This δ ribozyme possesses a specific on/off adapter (SOFA) that switches the cleavage activity from off (a “safety lock”) to on solely in the presence of the desired RNA substrate. In this report, we investigate the influence of both the structure and the sequence of each domain of the SOFA module. Analysis of the cleavage activity, using a large collection of substrates and SOFA-ribozyme mutants, together with RNase H probing provided several insights into the nature of the sequence and the optimal design of each domain of the SOFA module. For example, we determined that (1) the optimal size of the blocker sequence, which keeps the ribozyme off in the absence of the substrate, is 4 nucleotides (nt); (2) a single nucleotide difference between the substrate and the biosensor domain, which is responsible for the initial binding of the substrate that subsequently switches the SOFA-ribozyme on, is sufficient to cause nonrecognition of the appropriate substrate; (3) the stabilizer, which joins the 5′ and 3′ ends of the SOFA-ribozyme, plays only a structural role; and (4) the optimal spacer sequence, which serves to separate the binding regions of the biosensor and catalytic domain of the ribozyme on the substrate, is from 1 to 5 nt long. Together, these data should facilitate the design of more efficient SOFA-ribozymes with significant potential for many applications in gene-inactivation systems.

Keywords: ribozyme, riboswitch, substrate specificity, rational design, hepatitis B and C viruses

INTRODUCTION

The development of gene-inactivation systems is an active and important field for both functional genomics and gene therapy. In this context, ribozymes (i.e., RNA enzymes or Rz) that specifically recognize and then catalyze the cleavage of RNA molecules are attractive molecular tools (for reviews, see Bagheri and Kashari-Sabet 2004; Breaker 2004). They present an interesting alternative to the RNA interference (RNAi) approach to gene inactivation, especially given the fact that RNAi seems to trigger an immunological response (Sledz et al. 2003; Pebernard and Iggo 2004). However, in the past the use of ribozymes has faced several limiting factors, including delivery problems, effective concentration, activity in vivo, and cellular stability (e.g., Bagheri and Kashari-Sabet 2004). A ribozyme that has benefited from evolving as part of an RNA species that is naturally found within a given cell type should be better adapted and, consequently, should offer a greater chance of success in a given cell line. Following this rational, delta ribozyme (δRz), which is derived from the genome of human hepatitis delta virus (HDV), is a suitable candidate for the development of a gene inactivation system that would function in human cells (for review, see Bergeron et al. 2003). This hypothesis is well illustrated by the demonstration that δRzs benefit from an outstanding molecular stability in transfected cells (Lévesque et al. 2002). Several studies have already successfully used δRz to inhibit gene expression in vivo, confirming its great potential for use as a molecular tool (see Kato et al. 2001; Al-Anouti and Ananvoranich 2002; D’Anjou et al. 2004; Sheng et al. 2004).

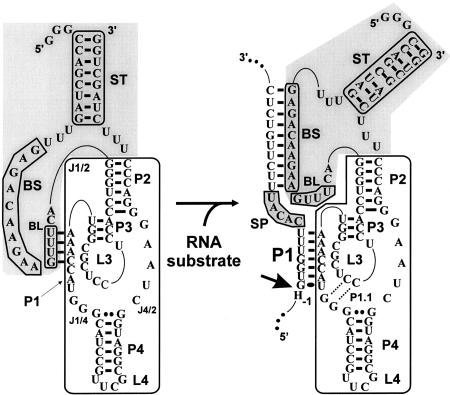

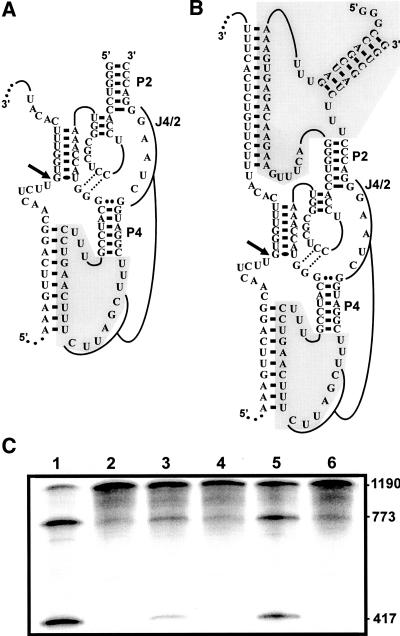

δRz folds into a compact secondary structure that includes pseudoknots (Fig. 1, white boxes; for review, see Shih and Been 2002). This structure is composed of one stem (the P1 stem), one pseudoknot (the P2 stem is a pseudoknot in the cis-acting version), two stem–loops (P3-L3 and P4-L4), and three single-stranded junctions (J1/2, J1/4, and J4/2). Both the J1/4 junction and the L3 loop are single-stranded in the initial stages of folding but are subsequently involved in the formation of a second pseudoknot that consists of two Watson-Crick base pairs (the P1.1 stem). The binding domain of δRz (the P1 stem) is composed of one G-U wobble base pair followed by six Watson-Crick base pairs (Perrotta and Been 1991; Nishikawa et al. 1999). In addition, the nucleotides (nt) from position − 1 to − 4 of the substrate—that is, those adjacent to the scissile phosphate, were shown to contribute to the ability of a substrate to be cleaved efficiently (Deschênes et al. 2000). Thus, the substrate specificity of δRz cleavage is based on a total of 11 nt, which might be a limiting factor when trying to specifically target an RNA species in a cell (Nielsen 2000).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of both the off and on conformations of SOFA-δRz-303. The gray section indicates the SOFA module; the white section, the original δRz-303. Each investigated segment is boxed in gray: the biosensor sequence (BS), the blocker (BL), the stabilizer (ST), and the spacer (SP). The bold arrow indicates the cleavage site. The H in position − 1 of the substrate represents A, C, or U.

To increase the substrate specificity of the δRz, a new version of this ribozyme bearing a specific on/off adapter (SOFA) (Fig. 1) was designed (Fig. 1; Bergeron and Perreault 2005). The SOFA module switches the cleavage activity from off (a “safety lock”) to on based solely on the presence of the appropriate substrate. There is no requirement for the presence of a third partner, as is the case for allosteric ribozymes. The SOFA module is composed of three domains: a blocker (BL), a biosensor (BS), and a stabilizer (ST). The blocker sequence of the SOFA module inhibits the cleavage activity of the ribozyme by binding, in cis, the P1 sequence that is part of the catalytic domain. An inactive version of the SOFA-δRz (i.e., a SOFA−, one harboring an unrelated biosensor sequence) showed a great “safety lock” capacity provided by the blocker domain, thereby diminishing the risk of nonspecific cleavage. The biosensor must bind its complementary sequence on the substrate in order to unlock the SOFA module, thereby permitting the folding of the catalytic core into the on conformation. Both the blocker and the biosensor have been shown to increase the substrate specificity of the ribozyme’s cleavage by several orders of magnitude compared with the wild-type δRz. This is due mainly to the addition of the biosensor domain that increases the binding strength of the δRz to its target but is also due to the fact that the blocker domain interacts with the P1 region and decreases its binding capacity. Finally, the presence of the stabilizer, which has no effect on the cleavage activity, stabilizes the RNA molecule in vivo against ribonucleases (Bergeron and Perreault 2005). Both proof-of-concept and the preliminary characterization of the SOFA-δRz that cleaves RNA transcripts derived from the hepatitis B and C viruses have been reported (Bergeron and Perreault 2005).

The molecular engineering of δRz bearing a target-dependent module that is activated by its RNA substrate provides a highly specific and improved tool offering significant potential for gene-inactivation systems. In this work, we investigate the influence of both the structure and the sequence of each domain comprising the SOFA module on the cleavage activity. Together, these data provide a better understanding of the mechanism of action of this man-made riboswitch, which, therefore, should further facilitate the design of more efficient SOFA-ribozymes.

RESULTS

The SOFA-δRz-303 ribozyme, which was shown to cleave transcripts derived from hepatitis B virus (HBV), was used in this study as it had previously been partially characterized for some features, including the kinetic parameters under single turnover conditions and the optimal biosensor size (i.e., 10 nt) (Bergeron and Perreault 2005). The experiments described herein have been designed to address the contribution of each component of the SOFA module to the optimal design.

Specificity conferred by the biosensor sequence

As a starting point, we were interested in establishing the substrate specificity for ribozyme cleavage conferred by the biosensor sequence. It has been shown that a SOFA-ribozyme, when activated by the proper substrate, does not cleave other substrates by either the cis- or trans-cleavage mechanisms (Bergeron and Perreault 2005). In one experiment, a ribozyme was incubated in the presence of 10 different small substrates possessing identical P1 binding sequences coupled to completely different biosensor binding sequences. This experiment led to the conclusion that each of the 10 ribozymes only cuts efficiently when the biosensor perfectly bound to the target RNA. However, it did not permit investigation of how the biosensor sequence identity influenced the substrate specificity. In order to address this issue, we performed two distinct experiments.

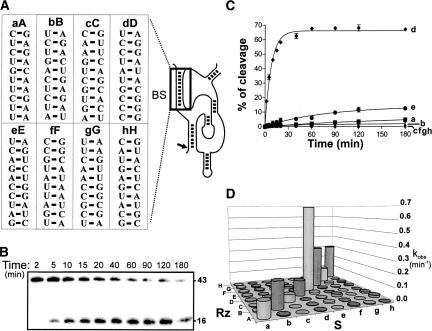

Initially, the cleavage activities of the eight most active SOFA-ribozymes from the collection described above were determined for each substrate alone, rather than within a pool. The substrates were arbitrarily designated a–h, while a ribozyme perfectly complementary (i.e., one with the appropriate biosensor, SOFA+) to a given substrate received the corresponding superscript letter, i.e., A–H (e.g., RzS = Aa) (Fig. 2A). These experiments were performed under single turnover conditions ([Rz] > [S]). Aliquots were removed at different intervals, fractionated on denaturing 10% polyacrylamide gels (PAGE) and analyzed by radio-analytic scanning. A typical gel for the couple Dd is shown in Figure 2B. The reaction time course for each substrate with ribozyme D is illustrated in Figure 2C. Only the perfectly matched couple Dd exhibited an active cleavage. The cleavage rate constant (kobs), as determined from at least two independent assays, was estimated for each RzS tested (64 couples) (Fig. 2D). This large data set prompted several observations. First, only the eight couples that had a perfect match between the biosensor and substrate sequences (located on the diagonal) had high kobs values. These kobs values varied between 0.056 and 0.69 min−1 (i.e., Cc and Ee, respectively). This difference of 12-fold in the kobs shows that the identity of the biosensor sequence significantly influenced the cleavage activity. The Gibbs free energy (ΔG) was predicted for the binding of the substrate to the biosensor for each couple. In general, the more stable the binding between the substrate and the biosensor, the higher the kobs (data not shown). Second, most of the imperfect couples, in which the number of mismatches varied between two and eight (the GU wobble was considered as base pair), exhibited cleavage activities characterized by significantly lower kobs. In several cases the skobs values for the cleavage of a mismatched substrate were three or more orders of magnitude smaller than that of their perfectly matched counterparts (e.g., Ac, Dg, and Hd). For example, ribozyme H cleaves substrate d with a rate constant 15,000 times smaller than it does substrate h. However, in most of the cases, the rate constants of imperfect couples were 25- to 300-fold lower. The general observation is that the catalytic parameters correlate directly with substrate specificity (i.e., the more active the ribozyme, the better its substrate specificity seemed to be). Other SOFA-ribozymes with different binding sequences also led to the same conclusion; i.e., they efficiently cleaved their desired substrates (i.e., that with the sequence complementary to the biosensor) but not other unrelated substrates (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrate the potential of the biosensor to improve the substrate specificity of a ribozyme.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of introducing mutations within the biosensor sequence. (A) Representation of the stems formed between eight pairs of substrate (a–h, left) and ribozyme biosensor (A–H, right) sequences. (B) Autoradiogram of a typical 10% denaturing PAGE gel of a time course experiment performed for the pair Dd. The sizes of the bands are indicated on the right of the gel. (C) Graphical representation of the time course of ribozyme D cleaving each of the substrates (a–h). (D) Histogram of the kobs values for each of the 64 possible pairs.

To obtain a more precise picture of the situation, a second experiment involving SOFA-δRz-303 sequence variants with less potential for forming mismatches was performed. Twenty-three mutated ribozymes, including one to four randomly distributed substitutions within the biosensor sequences, were synthesized (Fig. 3A). A residue of the biosensor was substituted for by the same base found at the corresponding position within the substrate, thereby producing a mismatch. The cleavage activity of each mutated ribozyme was assessed, and the rate constant (kobs) determined (Fig. 3A). Clearly, the decrease in the cleavage activity is directly related to the number of mutations (Fig. 3B). While the presence of a single mismatch reduced the kobs values from four- to 15-fold, the presence of four mutations yielded kobs values 18- to 106-fold smaller. The position of the mutation within the biosensor appeared to have only a small effect on the cleavage observed. However, a single mutation in the middle of the biosensor stem reduced the cleavage activity slightly more than did one located near the ends (Fig. 3A). This is probably due to the fact that a mismatch in the middle of the stem may interrupt the stacking. According to these data, the presence of only one mutation in the biosensor appears to be sufficient to significantly affect the cleavage activity. Two different mutants were produced for the positions 2, 6, 9, and 6–9, and the decrease in the cleavage activity was found to be similar regardless of the nature of the mutation (Fig. 3A). In addition, we also observed that the influence of a mutation in the biosensor was more important when targeting a long HBV-derived transcript (data not shown). This suggests that SOFA-δRz efficiently discriminate their substrate. The second-order rate constants (kcat/KM) of both the single and double mutants, SOFA-δRz-303(A6U) and (A6U)(A9U), were shown to be 25-fold lower than that of the original version (stars in Fig. 3A; see also Bergeron and Perreault 2005). Determination of the kinetic parameters of other single or double mutants also led to the same conclusion (i.e., the kcat/KM values of the mutants are at least one order of magnitude lower than that of the original SOFA-δRz-303, stars in Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Fine analysis of the biosensor sequences. (A) Twenty-three biosensor sequence variants were examined for their ability to cleave the short 44-nt HBV-derived substrate. They are clustered on the basis of the number of mutations (zero to four). The mutations are boxed in gray, and the kobs values (in min−1) are indicated on the right. The stars indicate the SOFA-δRz-303 mutants for which the kcat and K M values were determined for the cleavage of a long version of the HBV-derived substrate (1190 nt). (B) Graphical representation of the average values of kobs from at least two independent sets of experiments for each cluster of mutated ribozymes.

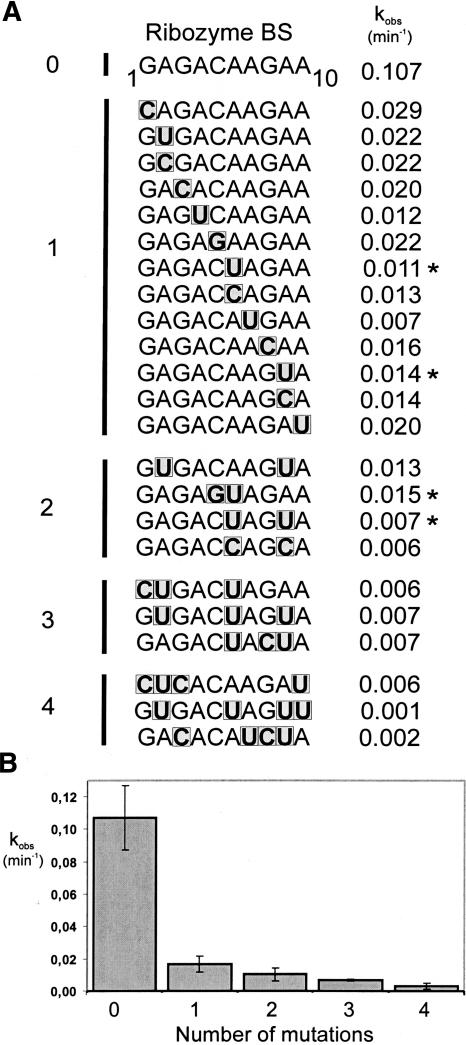

Characterization of the blocker sequence

In the absence of the appropriate target RNA substrate, the SOFA-ribozyme adopts an inactive conformation, the off conformation. According to the SOFA design, this state is due to the 4-nt blocker sequence binding the P1 region of the ribozyme, thereby preventing the binding of nonspecific substrates (Fig. 1). Consequently, the longer the blocker sequence, the better the “safety lock” effect. In order to verify this hypothesis, several SOFA-ribozymes with mutated blocker sequences were synthesized and their cleavage activities assessed by targeting the HBV-derived transcripts of 1190 nt. Since no mutation was required within the substrate, the longer transcript appeared to be more suitable for characterization because it is more relevant to a natural target. Different blocker lengths (0–5 nt) were used in order to find the largest stem that did not inhibit cleavage of the appropriate substrate (Fig. 4). In the absence of the blocker sequence, SOFA-δRz-303 was very active (i.e., BL-0 showed 81% cleavage). The same level of cleavage was detected in the presence of a 2-nt blocker sequence (i.e., BL-2 exhibited 79% cleavage), indicating that two bases were insufficient to allow the formation of a stable stem between the blocker and the ribozyme’s P1 strand. A SOFA-ribozyme with a 4-nt blocker sequence cleaved the substrate relatively efficiently, although at a reduced level compared with the previous assay (i.e., BL-4, 71%). Elongation of the blocker sequence by one more nucleotide significantly reduced the cleavage exhibited (i.e., BL-5, 40% of cleavage). In this case, it seems that the ribozyme remained locked in the off conformation, indicating that formation of the intra-molecular stem between the P1 region of the ribozyme and the blocker sequence seems to be favored over hybridization between the ribozyme and the substrate. Thus, a blocker sequence of 4 nt appears to be the optimal size to lock the ribozyme while still allowing it to unlock in the presence of the desired substrate. Time-course experiments of these four ribozymes confirmed that a blocker sequence of 4 nt is suitable for establishing a balance between the off/on conformations (Fig. 4C). Blockers of ≥ 6 nt were also tested (data not shown). In addition to blocking too much of the ribozyme in its inactive conformation (i.e., almost irreversible), we also observed ribozymes that self-cleaved the sequence adjacent to the blocker sequence (i.e., within the biosensor), an undesirable phenomena.

FIGURE 4.

Study of the blocker sequence. (A) Representation of the four blocker stems tested. (B) Autoradiogram of a 6% denaturing PAGE of the cleavage assays performed with the SOFA-δRz-303 variants possessing mutated blocker sequences (i.e., BL-X, where X indicates the size of the blocker stem). The reactions were performed under single turnover conditions by using the 1190-HBV substrate. The sizes of the bands are indicated on the right of the gel. The control (−) was performed in the absence of ribozyme. (C) Graphical representation of a kinetic analysis performed for each of the mutants: BL-0, squares; BL-2, circles; BL-4, inverse triangles; and BL-5, diamonds.

The sequence of the blocker segment might also modulate the level of inhibition. We observed that if a mutated blocker cannot form a stem with the P1 strand, then no inhibition is observed (data not shown). In contrast, previous experiments have shown that SOFA−-δRzs with different target sites on HBV-derived transcripts were all inactive (Bergeron and Perreault 2005). These ribozymes possessed the appropriate P1 strands and complementary blocker sequences, while their biosensor sequences could not bind the substrates. The inactivity of these SOFA−-δRzs confirmed that the blocker sequence plays its role by inhibiting the catalytic activity in the absence of the appropriate biosensor sequence. In all cases, the SOFA+-δRzs possessing a biosensor sequence capable of binding the substrate efficiently cleaved their substrates.

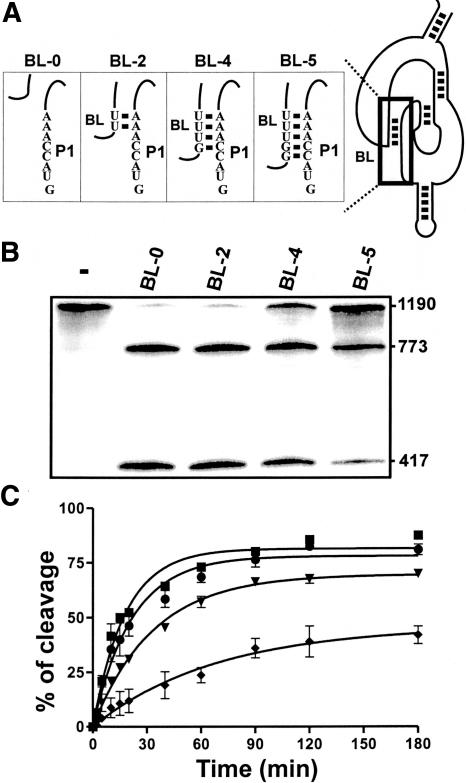

Spacing between the P1 stem and the biosensor binding domain

A SOFA-ribozyme recognizes its substrate through two independent domains, the biosensor and the P1 stem region. In all experiments reported so far, the two binding domains were separated by 5 nt simply to avoid the chance that the proximity and stacking of the P1 and biosensor would affect the release of the product. However, there was no scientific rational supporting this spacing of 5 nt. In order to investigate this parameter, seven model substrates possessing seven head-to-tail repetitions of the P1 stem domain (P1N) followed by the SOFA-δRz-303 biosensor sequence were synthesized (Fig. 5A). The substrates differed by possessing a distance of 0 to 6 nt between the domain bound by the biosensor and the first adjacent P1 binding sequence. In this way we created the equivalent of 49 different substrates that included different spacer lengths. The ribozyme should bind its complementary sequence at the 3′ end of the substrate via its biosensor, and should subsequently find a P1 sequence at an ideal distance. The cleavage experiments were performed during a short period of time (5 min) so as to permit only the unique cleavage reaction of 5′ end labeled substrates to occur. The substrates used in this experiment exhibited different electrophoretic mobilities depending on their sizes, which differed by 1 nt. The 5′ radiolabeled products of all cleavages made with the same P1 sequence migrated similarly on the gel because the one base difference was located within the nonradioactive 3′ product (Fig. 5B). We observed that all substrates were preferentially cleaved at the first or second sites near to the biosensor sequence (i.e., P11 and P12). With the exception of the substrate with no spacing between the P1 and biosensor domains, we observed that the higher level of cleavage occurred at the first P1 site (P11). In order to facilitate the interpretation of these data, we calculated the relative percentage of cleavage for all substrates (Fig. 5C). There is an increase in the percentage of cleavage as one progresses from no spacer to an optimal length of 3 nt. This is followed by a decrease up to a spacer of 21 nt, at which point the relative percentages of cleavage remain constantly low regardless of the length of these sequences. The decrease occurs mainly stepwise for substrates cleaved at their P12, P13, and P14 sequences, with a preference for the substrates with the smaller spacers (see dashed lines, Fig. 5C). This experiment shows that it is preferable to have at least a 1-nt space between the biosensor and the P1 region, and that the optimal length is found between 1 and 5 nt.

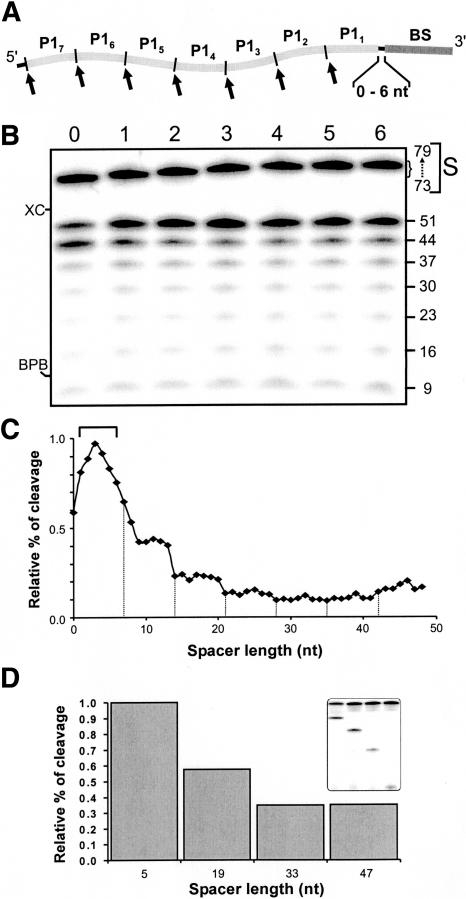

FIGURE 5.

Study of the spacer in the substrate. (A) Schematic representation of the design of the substrates used in this experiment. The substrate P1 strand of SOFA-δRz-303 was repeated seven times (P1N, 1–7) within seven substrates possessing spacers of different sizes (0–6 nt). (B) Autoradiogram of a 10% denaturing PAGE of the cleavage assays performed with each of the seven 5′ end labeled substrates. Lanes 0–6 correspond to the different sizes of the spacer sequences (i.e., from 0 to 6 nt). The migrations of the substrates (S) and their sizes, as well as those of the cleavage products, are indicated adjacent to the gel. XC and BPB indicate xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue, respectively. (C) Graphical representation of the relative percentage of cleavage as a function of spacer length. The bracket indicates the optimal length (1–5 nt), and dashed lines separate the observed transitions. (D) Histogram of the relative percentage of cleavage of the substrates possessing spacers of various lengths (5, 19, 33, and 47 nt). The inset shows the autoradiogram of the corresponding 10% denaturing PAGE gel.

We subsequently confirmed these results by using different substrates that harbor spacers of different lengths and a single cleavage site, as the normal SOFA-δRz does. Four substrates were designed based on the initial results obtained with the seven consecutive P1 stem domains. Each of these substrates contained only one P1 sequence, located in position P11, P13, P15, or P17 (i.e., 5′-GUGGUUU-3 ′). The other sequences were replaced by another that cannot be bound by the P1 strand of the ribozyme (i.e., 5′-UGUUGGU-3′). In this way, the spacer sequences were extended to 5, 19, 33, and 47 nt, respectively. All substrates were cleaved at different levels (Fig. 5D). We observed that the shorter a spacer is, the better the cleavage activity of the ribozyme. However, the difference between the shorter and longer spacers, in terms of cleavage activity, is not as significant as in the above experiment. In the present case, there is no competition between several sites, a condition that should enhance the level of catalytic activity regardless of the position of the cleavage site.

The sequence of the stabilizer stem does not influence the ribozyme cleavage

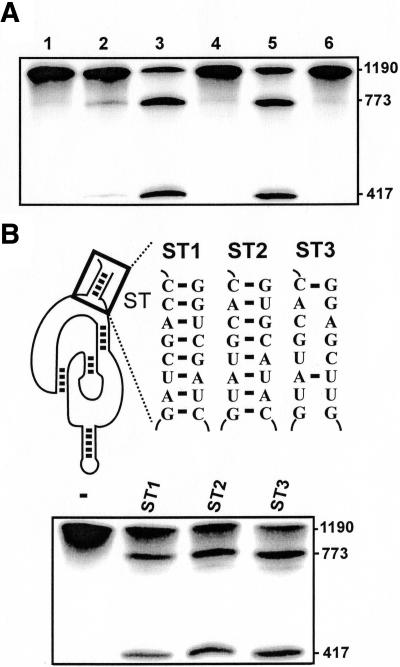

The stabilizer brings both the 5′ and 3′ ends into a common terminal stem. Both the SOFA+- and SOFA−-δRz-303 versions, with or without stabilizer sequences, were constructed and used to define the influence of this domain on the cleavage activity (Fig. 6A). As we first thought the two SOFA+-δRz-303 versions exhibited the same level of cleavage activity regardless of the presence (lane 3) or absence (lane 5) of the stabilizer sequences, while their SOFA− counterparts (i.e., those without the appropriate biosensor sequence) were inactive (lanes 4, 6). These observations confirmed that the stabilizer sequences did not interfere with the cleavage activity of the SOFA-ribozyme. Subsequently, the stabilizer was mutated to five different base pairs (Fig. 6B, SOFA-δRz-303-ST2 compared with -ST1) and used in the cleavage assay. As expected, both versions of SOFA-ribozyme exhibited virtually identical levels of cleavage. Similar results were observed if the mutation allowed the formation of only 2 bp within the stabilizer (Fig. 3B, SOFA-δRz-303-ST3 compared with -ST1). These results demonstrate that the identity of the stabilizer sequence does not affect the SOFA-module’s action.

FIGURE 6.

Evaluation of the effect of the stabilizer stem on the cleavage activity. (A) Autoradiogram of a 6% denaturing PAGE of cleavage assays of various SOFA-δRz-303 variants. Lane 1 is the incubation of the long HBV-derived substrate (1190 nt) alone, while lane 2 is that in the presence of the original δRz-303. Lanes 3,4 are the cleavage assays performed with SOFA+- and SOFA−-δRz-303, including the stabilizer stem, respectively. Lanes 5,6 are the cleavage assays performed with the SOFA+- and SOFA−-δRz-303 lacking the stabilizer stem, respectively. The sizes of the bands are indicated adjacent to the gel. (B) On the top are the representations of various stabilizer mutants (SOFA-δRz-303-ST1 to -ST3), while the bottom is the autoradiogram of the denaturing 6% PAGE of the corresponding cleavage assays. The control (−) was performed in the absence of ribozyme.

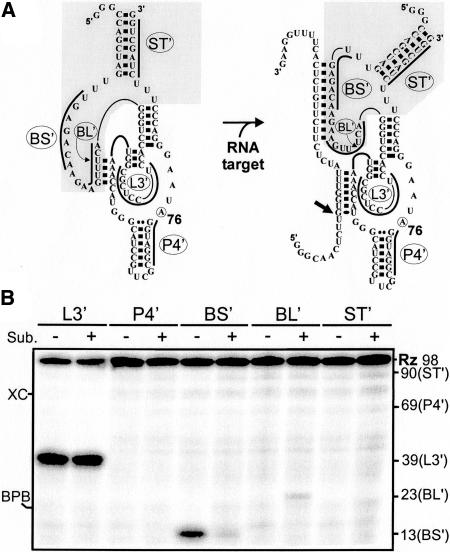

The predictive value of the determined rules

To validate the predictive value of the features determined above, a SOFA-δ ribozyme (SOFA-δRz-HCV) and several mutants that target a small substrate derived from the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) were synthesized. The SOFA+-δRz-HCV included both a 10-nt biosensor perfectly complementary to the substrate and a 4-nt blocker, while the substrate possessed a 5-nt spacer (Fig. 7A). This SOFA+-δRz-HCV exhibited a drastically improved level of cleavage of the 5′ end labeled substrate compared with the δRz-HCV, which lacks the SOFA module. More precisely this is a 30-fold increase in the cleavage efficiency between the two versions (i.e., 90% vs. 3%, respectively) (Fig. 7B, lanes 2,3). This constitutes another demonstration of the important contribution of the SOFA module to increasing the cleavage efficiency. When the blocker sequence was elongated by one more nucleotide, the level of cleavage decreased significantly to 54% (i.e., SOFA+-δRz-HCV-BL5, lane 4). The latter result is in agreement with the previous data showing that 5-nt blocker sequence seemed to keep the ribozyme locked in the off conformation. The mutation of the biosensor sequence in three positions (SOFA+-δRz-HCV-BS3, lane 5) was so detrimental to the level of cleavage that it became the same as that of SOFA−-δRz-HCV, a version that includes a biosensor that, in principle, forms no base pairs at all with the substrate (Fig. 7B, lanes 5,6, respectively). Moreover, if the spacer of the substrate was increased from 5 to 30 nt by changing the position of the substrate sequence complementary to the biosensor, the cleavage of the SOFA+-δRz-HCV was more than twofold smaller, showing the importance of preserving a short distance between these two regions (Fig. 7B, cf. lanes 7 and 2). More importantly, these results, as well as those of other mutations (e.g., smaller blocker sequence), demonstrate the predictive value of the results presented previously and clearly facilitate the design of more efficient SOFA-δRz.

FIGURE 7.

Evaluation of the predictive value of the determined rules. (A) Schematic representation of SOFA-δRz-HCV. The mutations in both the SOFA-δRz and the substrate are indicated in the shaded boxes. (B) Autoradiogram of a 6% denaturing PAGE gel of the cleavage assays of various SOFA-δRz-HCV variants. Lane 1 is the incubation of the substrate alone (−), while lane 2 is that in the presence of the original δRz-HCV. Lanes 3–5 are the cleavage assays performed with SOFA+-δRz-HCV, SOFA+-δRz-HCV-BL5, and SOFA+-δRz-HCV-BS3, respectively. Lane 6 is the cleavage assay with the SOFA− version of δRz-HCV, which possesses an unrelated bio-sensor sequence (i.e., 5′-AUAUAUAUAU-3′). Lane 7 is the cleavage assay performed with the substrate including a 30-nt spacer. The sizes of the bands and the position of the xylen cyanol (XC) are indicated adjacent to the gel.

Structural analysis of SOFA-δRz-303

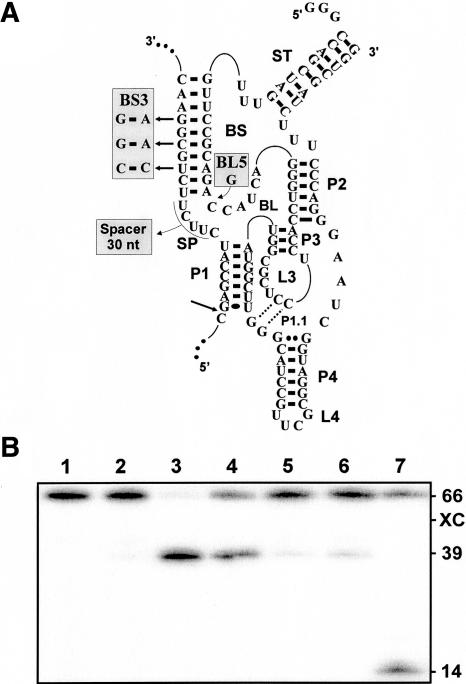

To probe both the off and on conformations of SOFA-δRz-303, small oligodeoxynucleotides 7 nt in length complementary to various domains of the ribozyme were synthesized and used with 5′ end labeled SOFA-ribozyme in either the absence (−) or the presence (+; in excess) of the 44-nt model substrate (Fig. 8). With the goal of preventing cleavage, we used an inactive SOFA-ribozyme in which the cytosine in position 76 is replaced by an adenosine. The RNA–DNA heteroduplexes were monitored by ribonuclease H (RNase H) hydrolysis, and the mixtures were analyzed on a denaturing PAGE gel (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

RNase H probing of SOFA-δRz-303. (A) Schematic representation of the SOFA-ribozyme in both the off and on conformations, respectively. The on conformation is obtained after the addition of the substrate. The bold lines indicate the oligodeoxynucleotides. In these experiments, a C76A (circled residue) mutant that is an inactive version of SOFA-δRz-303 was used. (B) Autoradiogram of an 8% denaturing PAGE of the probing assay. The symbols (−) and (+) indicate the presence or absence, respectively, of the substrate for the probing performed using each oligodeoxynucleotide (L3′, P4′, BS′, BL′, and ST′). The positions of the expected cleavage products, XC and BPB, are indicated adjacent to the gel.

The oligodeoxynucleotide complementary to the L3 loop (L3′) allowed the detection of a strong band of products in the absence of substrate, indicating that this region was single-stranded. A similar band was detected in the presence of the substrate because, under the conditions used, the hybridization of the oligodeoxynucleotide to the L3 loop is more stable than is the folding of the P1.1 stem that releases the oligodeoxynucleotide. Conversely, the oligodeoxynucleotide complementary to the P4 stem (P4 ′) did not permitted the detection of any products of RNase H hydrolysis, confirming that this region is double-stranded. The oligodeoxynucleotide complementary to the biosensor sequence (BS′) permitted the detection of a relatively abundant RNase H product only in the absence of the substrate, indicating that this region was single-stranded within the off conformation. Only a trace amount of the hydrolysis product was detected upon the addition of the substrate, showing that in the on conformation the biosensor is bound to its substrate and is thus double-stranded. The presence of the oligodeoxynucleotide complementary to the blocker sequence (BL′) gave the opposite pattern. No RNase H product was observed in the absence of the substrate, indicating that the blocker sequence was double-stranded (with the P1 strand of the ribozyme) in the off conformation. Conversely, cleavage product was detected in the presence of the substrate, indicating that, under these conditions, the blocker was single-stranded. However, a small amount of product was detected, regardless of the length of the oligodeoxynucleotide tested (e.g., slightly longer). We believe that this occurs because, as this region is central to the species, the RNase H hydrolysis may be limited due to steric hindrance reducing the accessibility to the RNA–DNA heteroduplex. Finally, an oligodeoxynucleotide complementary to the stabilizer (ST′) did not allow for the detection of any RNase H products, confirming that this region is double-stranded regardless of the presence or absence of the substrate. In conclusion, the three segments of sequence composing the SOFA module were shown to fold into the expected structure. Moreover, the structure of the blocker and biosensor sequences were observed to be involved in the conformational transition.

Redesigning the SOFA module

To investigate the flexibility of the SOFA module, two other versions of SOFA-δRz-303 were synthesized and their cleavage activities assessed (Fig. 9). We first tried to move the SOFA module from the P2 stem to the P4 stem, in order to obtain a ribozyme called SOFA-down (SOFA-δRz-DN, DN for down) (Fig. 9A). SOFA+-δRz-DN cleaved the transcripts relatively efficiently (Fig. 9C, lane 3). In contrast, SOFA−-δRz-DN (i.e., the one without an appropriate biosensor) was inactive, as expected (Fig. 9C, lane 4). Another variation was the construction of a “double” SOFA-ribozyme (SOFA+-δRz-DB, DB for double binding) (Fig. 9B). This ribozyme bound the substrate through the formation of three helices involving a total of 32 bp. The SOFA+ version exhibits a relatively high cleavage activity, while the SOFA− did not cleave the substrate (Fig. 9C, lanes 5,6). These results illustrate the gains in terms of substrate specificity, and also at the level of the “safety lock” action, obtained by using a blocker. It should be noted that the blocker domain of the SOFA module inserted in the L4 loop interacted with the sequence of the J4/2 junction, including the C76 of the ribozyme. The strategy was to injure the C76 position that is involved in the cleavage activity. The ensemble of these results clearly demonstrates that the SOFA module is amenable to various designs.

FIGURE 9.

Different conformations for the SOFA module. (A,B) The structures of SOFA+-δRz-Down (SOFA +-δRz-DN, module in the P4 stem) and SOFA+-δRz-Double Binding (SOFA+-δRz-DB, module in both the P2 and P4 stems), respectively. (C) Autoradiogram of a 6% denaturing PAGE gel of cleavage assays performed using these two ribozymes. Lanes 1,2 are the assays performed in the presence of SOFA +-δRz and SOFA−-δRz (module in the P2 stem). Lanes 3,4 are the assays performed in the presence of SOFA+-δRz-DN and SOFA−-δRz-DN. Lanes 5,6 are the assays in the presence of SOFA+-δRz-DB and SOFA−-δRz-DB. All reactions were performed under single turnover conditions. The lengths of the corresponding cleaved bands are indicated beside the gel.

DISCUSSION

We have decorticated the sequence segments that might influence the efficiency of the SOFA module. Initially, the SOFA-ribozyme is in an inactive conformation due to the action of the blocker sequence that formed a stem with the ribozyme’s P1 strand, acting as a safety lock (Fig. 1). RNase H probing of the ribozyme alone supports the hypothesis that the blocker is engaged in a double-stranded region, while the biosensor sequence remains single stranded and accessible (Fig. 8). The optimal size for the blocker sequence was determined to be 4 nt (Fig. 4). Smaller blockers did not sufficiently prevent the ribozyme’s activity, while longer blockers appeared to lock the ribozyme in its inactive conformation. Moreover, we observed that the action of the blocker sequence of various SOFA-ribozymes could not be correlated with the identity of the residues composing this segment. Thus, a higher GC content in the blocker was not responsible for the lower activity of some of the SOFA-ribozymes. Regardless, there was competition between the blocker (4 bp) and the substrate (7 bp) for the P1 sequence; therefore, a higher GC content on one strand would be counterbalanced by a higher concentration on the other strand.

In the presence of the desired substrate, the biosensor binds the complementary substrate sequence, leading in the release of the ribozyme’s P1 stem from the blocker (Fig. 1). The RNase H probing of the SOFA-ribozyme-substrate complex strongly suggest that the biosensor is base-paired with the substrate while the blocker becomes susceptible to RNase H hydrolysis, indicating that it is single-stranded (Fig. 8). Kinetic experiments have previously shown the optimal size of the biosensor to be 10 nt (Bergeron and Perreault 2005). We demonstrated that each SOFA-ribozyme in our collection efficiently cleaved only the substrate containing the sequence complementary to its biosensor (Fig. 2). Substrates that included sequence with several mutations in the binding region of the biosensor were poorly cleaved. Under single turnover conditions ([Rz] > [S]), which should favor cleavage of even imperfectly base-paired substrates, only a residual rate of cleavage was observed. A similar conclusion was obtained when investigating a biosensor possessing a small number of mutations (Fig. 3). As expected, the decrease in the cleavage activity was inversely proportional to the number of mutations (ranging from four- to 106-fold smaller in terms of kobs). In the presence of a single mutation, the reduction was estimated to be from four- to 15-fold. However, the determination of the kinetic parameters for some mutated ribozymes led us to observe larger effects in terms of the second-order rate constant (kcat/KM 25-fold smaller) (Bergeron and Perreault 2005). It should be noted that most of these experiments were performed by using small substrates. A more important effect was observed with several of these SOFA-ribozymes when they were tested for the cleavage of the longer HBV-derived transcript (e.g., 1190 nt; data not shown). More importantly, a reduction of approximately one order of magnitude is probably sufficient for the ribozyme to be able to discriminate between two substrates in a cell. The SOFA-ribozyme has demonstrated an activation of cleavage of as much as 15,000-fold, with an average increase of >800-fold. In other words, the SOFA system brings a two order of magnitude increase in the specificity of the ribozyme’s action. Clearly, the SOFA-module provides the ribozyme with an improved substrate specificity. A statistical analysis has demonstrated that SOFA-ribozymes are specific enough to target only one RNA species at the time from the human transcriptome (Bergeron and Perreault 2005).

In both the inactive and active conformations, the SOFA-ribozymes harbor a stabilizer stem that joins the sequence found at the 5′ and 3′ ends into a stem (Fig. 1). In terms of mechanism, it appears clear that the stabilizer does not have an active role in the SOFA module other than the improvement of the structure’s stability. This conclusion receives additional physical support from the observation that some mutated stabilizer sequences that either preserve or destroy double-stranded structure do not modify the level of cleavage activity (Fig. 6; data not shown).

Finally, the length of the spacer sequence was investigated. The spacer sequence is not part of the SOFA-module, but it is an important parameter that influences the cleavage level. The spacer is the sequence located between the substrate P1 strand domain and the sequence complementary to the bio-sensor (Fig. 1). It was shown that a minimal spacer of at least 1 nt was preferable. Moreover, short spacer sequences (1–5 nt) appeared to have higher levels of cleavage than did longer ones (Fig. 5). Most likely, the binding of the biosensor favors the subsequent formation of the P1 stem between the ribozyme and the substrate when the spacer is short.

Together, these experiments with SOFA-δRz-303 yield a better understanding of the contribution of each of the different domains of the SOFA module. The data obtained with other ribozymes demonstrate that our findings are not restricted to SOFA-δRz-303 but rather can be applied to other SOFA-δRzs (Fig. 7). Moreover, the analysis of a large collection of biosensor sequences for SOFA-δRz-303 demonstrated the discrimination potential of this domain. Prediction of the ΔG was performed for the binding of the substrate to the SOFA-Rz for many perfectly and imperfectly bound couples for which the kobs were determined (data not shown). Overall, the more stable a ribozyme–substrate complex is in terms of ΔG, the higher its cleavage activity. Since the P1 region that binds the substrate is not altered, this indicates that the biosensor-substrate stability is important for the prediction of the most efficient SOFA-ribozymes. However, it is important to remember that several other factors might also influence the level of cleavage. For example, we can imagine that some domain of the SOFA could fold into small RNA motifs either alone (i.e., forming a hairpin) or with another domain of the RNA molecule (i.e., forming a stem). Such ribozyme misfolding cannot be totally excluded; even natural RNA sequence can adopt alternative conformations. More importantly, the present findings will help in the design of efficient SOFA-ribozymes with significant potential for many applications in gene-inactivation systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HBV substrate and ribozyme DNA constructs

The HBV-derived constructs were described previously (Bergeron and Perreault 2005). Briefly, the HBV 1190-nt fragment was excised from pCHT9/3091 (Nassal 1992) by using SacI and EcoRI and then sub-cloned into pBlueScript SK, generating pHBV-1190. The shorter HBV 44-nt substrate was produced by using a PCR-based strategy with T7 sense primer (5′-TTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) and antisense primer (5′-CTTCCAAAAGTGAGACAAGAAATGTGAAACCACA AGAGTTGCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′). The same strategy was used to construct substrates a–h (for the sequences of the anti-sense primer, see Table 1). For the substrates with seven different spacer lengths, the antisense primers were as follows: 5′-AAAGTGAGACAAGAA-(A)0-6nt-(AAACCAC)7AAAAAACCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′, where the T7 promoter sequence is underlined. For the substrates with the spacers of different lengths but possessing a unique cleavage site, the antisense primers were as follows: 5 ′-AAAGTGAGACAAGAA(AAAAC)SP-(ACCAACA)X(AAACCAC) Y (ACCAACA)Z-AAAAAACCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3 ′ (where SP is for spacer, the number of X and Z units varied as desired, the unit Y gives the cleavable P1 sequence, and the T7 promoter sequence is underlined). In these cases, the spacer was always 5′-AAAAC-3′, except for the substrate of 5 nt that included the sequence 5 ′-AAAAA-3′. This was required in order to avoid nonspecific cleavage. The substrate derived from the HCV IRES with a 5-nt spacer was synthesized starting from the antisense primer: 5′-AAAGTGTTCCGCAGAAGAAGATGGCTC(GAA) 10 AAAAAACCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA-3′, where the T7 promoter sequence is underlined. For the version with a 30-nt spacer, the antisense primer was 5′-AAAGTGTTCCGCAGA(GAA) 10 ATGGCTC(AGA)2AAAAACCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3 ′. Both the original and SOFA-δRz were constructed as described previously (Bergeron and Perreault 2002, 2005, respectively). SOFA+/−-ribozymes were constructed by using a PCR-based strategy that included two complementary and overlapping oligodeoxynucleotides: the antisense oligonucleotide (5 ′-CCAGCTAGAAAGGGTCCCTTAGCCATCCGCGAACGGATGCCC (ATGGTTT)P1ACCGCGAGGAGGTGGACCCTG(N) 0-5BL -3′, where N is A, C, G, or T, and P1 and BL indicate the P1 strand region and the blocker sequence, respectively); and the sense primer (5′-TTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCAGCTAGTTT(N)10-15BS (N)0-5 -BLCAGGGTCCACC-3 ′, where N is A, C, G, or T, and BS indicates biosensor sequence and BL the blocker sequence, respectively, that permitted incorporation of the T7 RNA promoter (underlined). It is important to note that the (N) segments varied in size depending on the construct. The same strategy using two oligodeoxynucleotides was used to build the different versions of the ribozyme. The PCR products were purified by phenol:chloro-form extraction, precipitated with ethanol, and dissolved in water. In vitro transcriptions and purifications of the ribozymes were then performed as described below. The SOFA−-δRz-303 possesses either the sequence 5′-GAAC ATCGGTATCAC-3 ′or 5 ′-TCGGTATCAC-3′ as biosensor, depending on the experiment.

TABLE 1.

Oligodeoxynucleotide sequences of the a–h substrates

| a | 5′-AAAGTGAGACAAGAAATGTGAAACCAC/AAGAGCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′ |

| b | 5′-AAAGTAGACTGAGATATGTGAAACCAC/AAGAGTGTACTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′ |

| c | 5′-AAAGTGTTCAGCACTATGTGAAACCAC/AAGAGTGTACTGTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′ |

| d | 5′-AAAGTAGGATACGGGATGTGAAACCAC/AAGAGTGTACTGTAACCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′ |

| e | 5′-AAAGTAGTCTGGATCATGTGAAACCAC/AAGAGTGTACTGTAACTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′ |

| f | 5′-AAAGTGGCATAATCAATGTGAAACCAC/AAGAGTGTACTGTAACTTCCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′ |

| g | 5′-AAAGTAAGTTGGCGAATGTGAAACCAC/AAGAGTGTACTGTAACTTCAACCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′ |

| h | 5′-AAAGTGTACTCATGCATGTGAAACCAC/AAGAGTGTACTGTAACTTCAATGCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAA-3′ |

The slash (/) indicates the P1 cleavage site. The biosensor binding sequence is underlined.

RNA synthesis

Both ribozymes and substrates were synthesized by run-off transcription from PCR products, SmaI linearized pδRz-HBV303 (original ribozyme) and HindIII linearized plasmid pHBV-1190 templates. Run-off transcriptions were performed, and the resulting transcripts were purified, as described previously (Bergeron and Perreault 2002). Briefly, transcriptions were performed in the presence of purified T7 RNA polymerase (10 μg), RNA Guard (24 U, Amersham Biosciences), pyrophosphatase (0.01 U, Roche Diagnostics), and either linearized plasmid DNA (5 μg) or PCR product (2 to 5 μM) in a buffer containing 80 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 24 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 40 mM DTT, 5 mM of each NTP, and either with or without 50 μCi [α-32P]GTP (3000 Ci/mmol, New England Nuclear) in a final volume of 100 μL for 2–4 h at 37°C. Upon completion, the reaction mixtures were treated with DNase RQ1 (Amersham Biosciences) for 20 min at 37 °C; the RNA was purified by phenol:chloroform extraction and then precipitated with ethanol. The RNA products were fractionated by denaturing (6% or 10%) PAGE (19:1 ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide) in buffer containing 45 mM Tris-borate (pH 7.5), 7 M urea, and 1 mM EDTA. The reaction products were visualized either by UV shadowing or autoradiography. The bands corresponding to the correct sizes for both the ribozymes and the substrates were cut out and the transcripts eluted overnight at room temperature. The transcripts were desalted by using Sepha-dex G-25 (Amersham Biosciences) spun-columns, ethanol precipitated, washed, dried, and resuspended in water, and the quantity was determined by either 32P counting or absorbance at 260 nm.

Substrate RNAs and SOFA-δRz (20 pmol) were dephosphorylated in a final volume of 20 μL containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 0.1 mM EDTA, 40 U of RNAGuard, and 0.2 U of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Roche Diagnostic) for 30 min at 37°C and were then purified by extracting twice an equal volume of phenol:-chloroform and ethanol precipitating. The resulting RNAs were 5′ end labeled in a final volume of 10 μL containing 1.6 pmol [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, New England Nuclear) and 3 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase as recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences). The reaction mixtures were fractionated on PAGE gels, and the RNA species recovered as described previously.

Ribozyme cleavage assays

The conditions for the ribozyme cleavages assays were as described previously (Mercure et al. 1998; Bergeron and Perreault 2005). Both the ribozymes and substrates were preincubated together for 2–5 min at 37°C, and the magnesium was then added in order to initiate the cleavage. Except when indicated, all reactions were performed under single turnover conditions ([Rz]>[S]) using 1 μM ribozyme and trace amounts of either internally 32P-labeled or 32P 5′ end labeled substrates at 37°C in a final volume of 10 μL containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 10 mM MgCl2. For the time course experiments, aliquots (0.8 μL) were removed at various times up to 4 h and were quenched by the addition of ice-cold formamide dye buffer (5 μL of 97% formamide, 10 mM EDTA at pH 8.0, 0.025% xylene cyanol, 0.025% bromophenol blue), electrophoresed on 6%–20% PAGE gels, and the gels were analyzed with a radioanalytic scanner (Storm).

RNase H hydrolysis of SOFA-δRz-303

Trace amounts of 5′ end labeled SOFA-δRz-303 (~10,000 c.p.m; <0.1 pmol) in the presence of 50 pmol of either the unlabeled small substrate (44 nt) or yeast tRNA as carrier (Roche Diagnostic) were preincubated in a volume of 8 μL containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 25 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 0.13 mM EDTA, and 0.13 mM DTT for 10 min at 25°C. Then oligodeoxynucleotides (L3′: 5′-GCGAGGA-3′; P4′: 5′-CCATCCG-3′; BS′: 5′-TGTCTCA-3′; BL′: 5′-TGAAACT-3′; ST′: 5′-CAGCTAG-3′) 7 nt in size (10 pmol; 1 μL) were separately added to the samples before preincubating for another 10 min. Finally, Escherichia coli RNase H (2 U, Ambion) was added to the mixtures and the samples incubated for 10 min at 37°C. The reactions were quenched by adding 5 μL of ice-cool formamide dye buffer, the samples were fractionated on denaturing 8% PAGE gels, and the gels were analyzed with a radio-analytic scanner.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Provencher-Dionne, M. Lévesque, F. Brièe, and D. Lévesque for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR, grant nos. MOP-44002 and EOP-38322) to J.P.P. The RNA group is supported by grants from Université de Sherbrooke. L.J.B. was the recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from CIHR. J.P.P. is an investigator from the CIHR.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2112705.

REFERENCES

- Al-Anouti, F. and Ananvoranich, S. 2002. Comparative analysis of antisense RNA, double stranded RNA, and delta ribozymemediated gene regulation in toxoplasma gondii. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 12: 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, S. and Kashani-Sabet, M. 2004. Ribozymes in the age of molecular therapeutics. Curr. Mol. Med. 4: 489–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron, L.J. and Perreault, J.P. 2002. Development and comparison of procedures for the selection of delta ribozyme cleavage sites within the hepatitis B virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 4682–4691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2005. Target-dependent on/off switch increases ribozyme fidelity. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 1240–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron, L.J., Ouellet, J., and Perreault, J.-P. 2003. Ribozyme-based gene-inactivation systems require a fine comprehension of their substrate specificities: The case of delta ribozyme. Curr. Med. Chem. 10: 2589–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaker, R.R. 2004. Natural and engineered nucleic acids as tools to explore biology. Nature 432: 838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anjou, F., Bergeron, L.J., Larbi, N.B., Fournier, I., Salzet, M., Perreault, J.-P., and Day, R. 2004. Silencing of SPC2 expression using an engineered δ ribozyme in the mouse βTC-3 endocrine cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 14232–14239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes, P., Lafontaine, D.A., Charland, S., and Perreault, J.P. 2000. Nucleotides -1 to -4 of hepatitis δ ribozyme substrate increase the specificity of ribozyme cleavage. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 10: 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes, P., Ouellet, J., Perreault, J., and Perreault, J.P. 2003. Formation of the P1.1 pseudoknot is critical for both the cleavage activity and substrate specificity of an antigenomic trans-acting hepatitis delta ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Y., Kuwabara, T., Warashina, M., Toda, H., and Taira, K. 2001. Relationships between the activities in vitro and in vivo of various kinds of ribozyme and their intracellular localization in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 15378–15385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, D., Choufani, S., and Perreault, J.P. 2002. Delta ribozyme benefits from a good stability in vitro that becomes outstanding in vivo. RNA 8: 464–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercure, S., Lafontaine, D., Ananvoranich, S., and Perreault, J.-P. 1998. Kinetic analysis of δ ribozyme cleavage. Biochemistry 37: 16975–16982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassal, M. 1992. The arginine-rich domain of the hepatitis B virus core protein is required for pregenome encapsidation and productive viral positive-strand DNA synthesis but not for virus assembly. J. Virol. 66: 4107–4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, P.E. 2000. Peptide nucleic acids: On the road to new gene therapeutic drugs. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 86: 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa, F., Roy, M., Fauzi, H., and Nishikawa, S. 1999. Detailed analysis of stem I and its 5′ and 3′ neighbor regions in the transacting HDV ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebernard, S. and Iggo, R.D. 2004. Determinants of interferon-stimulated gene induction by RNAi vectors. Differentiation 72: 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, A.T. and Been, M.D. 1991. A pseudoknot-like structure required for efficient self-cleavage of hepatitis delta virus RNA. Nature 350: 434–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, J., Al-Anouti, F., and Ananvoranich, S. 2004. Engineered delta ribozymes can simultaneously knock down the expression of the genes encoding uracil phosphoribosyltransferase and hypoxanthinexanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase in Toxoplasma gondii. Inter. J. Parasitol. 34: 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih, I.H. and Been, M.D. 2002. Catalytic strategies of the hepatitis delta virus ribozymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71: 887–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledz, C.A., Holko, M., de Veer, M.J., Silverman, R.H., and Williams, B.R. 2003. Activation of the interferon system by short-interfering RNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 5: 834–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]