Abstract

The spliced-leader (SL) RNA plays a key role in the biogenesis of mRNA in trypanosomes by providing the m7G-capped SL sequence to the 5′ end of every mRNA. The cap structure of the SL RNA is unique in eukaryotes with 4 nucleotides after the cap carrying a total of seven methyl groups and by convention is referred to as “cap 4”. Although the enzymatic machinery for cap addition has been characterized in several organisms, including Trypanosoma brucei, the identification of methyltransferases dedicated to the generation of higher order cap structures has lagged behind, except in viruses. Here we describe T. brucei MT57 (TbMT57), a primarily nuclear polypeptide with structural and functional similarities to vaccinia virus VP39, a bifunctional protein acting at the mRNA 5′ end as a cap-specific 2′-O-methyltransferase. Down-regulation by RNAi or genetic ablation of TbMT57 resulted in the accumulation of SL RNA missing 2′-O-methyl groups at positions +3 and +4 and thus bearing a cap 2 rather than a cap 4. Furthermore, competitive binding studies indicated that modifications at the +3 and +4 positions are important for binding to the nuclear cap-binding complex. Genetic ablation of MT57 resulted in viable cells with no apparent defect in SL RNA trans-splicing, suggesting that MT57 is not essential or that trypanosomes have developed alternate mechanisms to counteract the absence of this protein. Interestingly, MT57 homologs are only found in trypanosomatid protozoa that have a cap 4 structure and in poxviruses, of which vaccinia virus is a prototype.

Keywords: cap 4 modification, 2′-O-methyltransferase, trans-splicing, SL RNA, RNAi

INTRODUCTION

The biogenesis of mRNA in trypanosomatids includes trans-splicing of a 39-nucleotide (nt) leader sequence from the spliced-leader RNA (SL RNA) to the 5′ end and cleavage/ polyadenylation at the 3′ end of the coding region (Liang et al. 2003). Trans-splicing is also a trans-capping reaction in that mRNAs acquire the 5′-terminal cap from the SL RNA and not co-transcriptionally, as it is the case in most other eukaryotes. The mRNA cap structure in trypanosomatids, which is identical to that of the SL RNA, is unique in the eukaryotic kingdom in terms of its high content of modified nucleotides. In higher eukaryotes the distinctive 5′-terminal structure of mRNAs consists of a 7-methylguanosine residue linked to the first transcribed nucleotide by a 5′ to 5′ triphosphate bridge (m7GpppN or cap 0), and most often the first and second transcribed nucleotide are further modified by the addition of 2′-O-methyl groups leading to cap 1 and cap 2 structures. In contrast, the mRNA cap structure present in trypanosomatids turned out to be more complex. Whereas the terminal residue is a conventional m7G, a total of seven methyl groups are added to the first four transcribed nucleotides and thus, by convention, this structure was named “cap 4” (Freistadt et al. 1987, 1988; Perry et al. 1987; Bangs et al. 1992). Using a combination of liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, the cap 4 was determined to be 7-methyl-guanosine-ppp-N6,N6,2′-O-trimethyladenosine-p-2′-O-methyl-adenosine-p-2′-O-methylcytosine-p-N3,2′-O-dimethyl-uridine (Bangs et al. 1992). Although trans-splicing is present in a diverse spectrum of eukaryotes (Nilsen 2001), currently there is no evidence for the existence of a cap 4 structure outside trypanosomatid organisms.

Several observations from our laboratory have supported the view that in permeable trypanosome cells proper modification of the SL RNA 5′ end is required for efficient utilization of the SL RNA in pre-mRNA trans-splicing in Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania amazonensis (Ullu and Tschudi 1991, 1995). These studies also revealed that the cap 4 modifications are not required for the assembly of the SL RNA into a core ribonucleoprotein particle (RNP), for the stability of the SL RNA or for the proper folding of the SL RNA in vivo (Harris et al. 1995). In addition, genetic analysis in Leptomonas collosoma revealed that each of the four nucleotides of the cap 4 plays a crucial role for SL RNA function in trans-splicing (Mandelboim et al. 2002). However, the most dramatic phenotypes were obtained by replacement of nucleotides at positions +1, +2 and +3, whereas substitution of position +4 led only to partial inhibition of trans-splicing utilization of the SL RNA. More recently, it was shown that down-regulation of the Sm proteins D1 and E led to the accumulation of hypomethylated SL RNA carrying modifications only at positions +1 and +2 of the cap 4 structure (Mandelboim et al. 2003; Zeiner et al. 2004). This SL RNA was shown to be deficient in trans-splicing, but it is unclear whether this effect was due to the lack of modifications, to the down-regulation of several U snRNAs that are essential trans-splicing cofactors, or to formation of aberrant SL RNA complexes that assemble in the absence of a complete set of Sm proteins. Lastly, in T. brucei the cap 4 structure is specifically recognized by an unusual nuclear cap-binding complex (CBC) that contains three subunits unique to trypanosomatids (Li and Tschudi 2005). Although down-regulation of several individual components of the CBC by RNAi demonstrated an essential function at an early step in trans-splicing, a specific role for the modified nucleotides in binding the CBC has not been elucidated.

Here we report the identification of T. brucei MT57, a protein that bears striking similarity both in structure and function to VP39, a bifunctional protein that acts as a cap-specific 2′-O-methytransferase and as a stimulating factor for poly(A) tail elongation (Barbosa and Moss 1978). TbMT57 acts upon the cap structure of the SL RNA by methylating the ribose moiety at position +3, and possibly at position +4.

RESULTS

T. brucei proteins related to the vaccinia virus VP39 cap 2′-O-methyltransferase/poly(A) polymerase processivity factor

Through database mining with known RNA methyltransferases we identified two T. brucei polypeptides with significant homology with vaccinia virus VP39, a bifunctional protein involved in the maturation of both ends of nascent viral transcripts (Barbosa and Moss 1978; Schnierle et al. 1992). At the 5′ end, the protein acts as a cap-specific mRNA nucleoside-2′-O-methyltransferase by converting cap 0 (m7GpppN . . . ) to the cap 1 (m7GpppNm . . . ) form (Barbosa and Moss 1978). At the mRNA 3′ end, VP39 acts in poly(A) tail elongation as the smaller subunit of the heterodimeric vaccinia virus poly(A) polymerase (Gershon et al. 1991; Gershon and Moss 1993). The larger subunit VP55 provides the poly(A) polymerase catalytic activity. The two T. brucei proteins of 48 and 57 kDa with homology with VP39 were named TbMT48 (GeneDB accession no. Tb11.02.2500) and TbMT57 (GeneDB accession no. Tb09.211.3130), respectively, according to their predicted molecular weight. Mining of the current genome databases revealed homologs of TbMT48 and TbMT57 only in trypanosomatid protozoa, including Leishmania major, T. cruzi, T. congolense, and T. vivax (data not shown), thus suggesting that the function of these proteins is specific to this group of organisms.

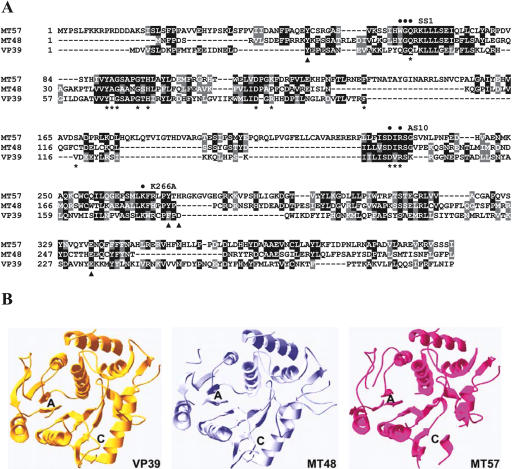

Using the T-COFFEE program (Notredame et al. 2000) amino acids 1–297 of VP39, present in the crystal structure (Hodel et al. 1996), were aligned with TbMT48 (amino acids 1–310) and TbMT57 (amino acids 1–404). This alignment revealed that TbMT48 shares considerable similarity with VP39: Amino acids 18–260 of TbMT48 are 26% identical (43% similar) with residues 22–240 of VP39 (Fig. 1A ▶). On the other hand, the similarity between TbMT57 and VP39 is restricted to the N terminus and less pronounced in the remainder of the molecule. Nevertheless, the majority of the amino acids forming the adenosyl-methionine (AdoMet) binding site in the crystal structure of VP39 complexed with AdoMet (Hodel et al. 1996) are conserved in the two trypanosome proteins (indicated by asterisks in Fig. 1A ▶). In addition, the co-crystal between VP39 and cap analogs highlighted four residues mediating the interaction between m7guanine and the protein (Hodel et al. 1997) (indicated by filled triangles in Fig. 1A ▶). Three of these amino acids are conserved in the trypanosome proteins, whereas the fourth residue (D182) was shown by mutational analysis not to be critical for cap binding of VP39 (Hodel et al. 1997). Thus, two characteristic features of VP39, namely the cap- and AdoMet-binding sites, appear to be conserved in TbMT48 and TbMT57. To further probe the relationship between VP39 and the two trypanosome proteins, we performed three-dimensional structure modeling. By means of the alignment interface of SWISS-MODEL the vaccinia virus VP39 crystal structure was used as a template to generate models for TbMT48 and TbMT57 (Fig. 1B ▶). The model of MT48 has many structural similarities to VP39, including domains predicted to be involved in AdoMet and cap binding. Considering the overall low sequence conservation and the many insertions in TbMT57 relative to VP39, the model for this protein is less convincing. Nevertheless, on the basis of the sequence and structural conservation with VP39, we hypothesized that TbMT48 and/or TbMT57 are cap-specific 2′-O-methyltransferases that may have a role in the biogenesis of the SL RNA cap 4 structure.

FIGURE 1.

Bioinformatics analysis of TbMT48 and TbMT57. (A) Sequence alignment of TbMT48 (GeneDB accession no. Tb11.02.2500), TbMT57 (GeneDB accession no. Tb09.211.3130), and VP39 using the T-COFFEE program (Notredame et al. 2000). Note that the alignment was restricted to VP39 amino acids present in the crystal structure (Hodel et al. 1996). Asterisks and filled triangles below the VP39 sequence indicate residues in the AdoMet and m7guanine binding pocket, respectively. Filled circles above the MT57 sequence indicate residues targeted for mutagenesis. (B) Ribbon diagram of VP39 secondary structure elements (PDB ID 1VPT; left panel) and of the predicted models of MT48 and MT57 (middle and right panels). The approximate position of the AdoMet (A) and m7G (C) binding pocket is indicated.

MT57 is required for SL cap 4 modification and is predominantly localized in the nucleus

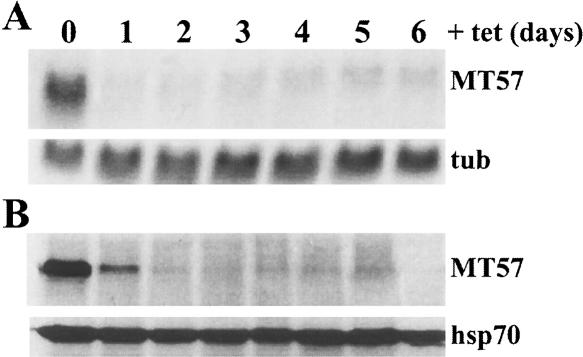

To investigate the possibility that TbMT48 and TbMT57 were part of the enzymatic machinery modifying the nucleotides adjacent to the SL RNA m7G-cap, we down-regulated expression of each of the two proteins by RNA interference (RNAi) using a hairpin-type construct under the control of a tetracycline (tet)-inducible promoter. Initial experiments revealed that TbMT48 down-regulation by RNAi appeared to have a minor effect on the SL RNA cap 4 structure, as assayed by primer extension (data not shown), and the function of this polypeptide in SL RNA modification is currently under study. In contrast, tet-induced TbMT57-RNAi trypanosomes showed a clear defect in cap 4 methylation, and thus we chose to characterize this protein in more detail. Figure 2A ▶ shows that over the time course of tet induction, TbMT57 mRNA significantly declined in abundance after 24 h, whereas the protein reached a minimum after 48 h (Fig. 2B ▶). It is important to note that MT57 RNAi did not ablate protein levels and that trace amounts of the protein were detected throughout the period of down-regulation. Furthermore, silencing of TbMT57 mRNA by RNAi did not produce a lethal phenotype, as MT57-RNAi trypanosomes remained viable throughout the course of the experiment shown in Figure 2 ▶ and even after 10 d of tet induction, although in some experiments we noticed a slight increase in doubling time in the later stages of induction (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

RNAi of T. brucei MT57. (A) The MT57 RNAi cell line was induced with tetracycline for the indicated number of days and total RNA was probed for MT57 mRNA (MT57). Hybridization to α-tubulin mRNA (tub) served as a loading control. (B) Total extracts from RNAi cells as described above were probed by Western blot with an anti-BB2 antibody (MT57) to monitor epitope-tagged MT57. A Western blot for endogenous hsp70 served as a loading control.

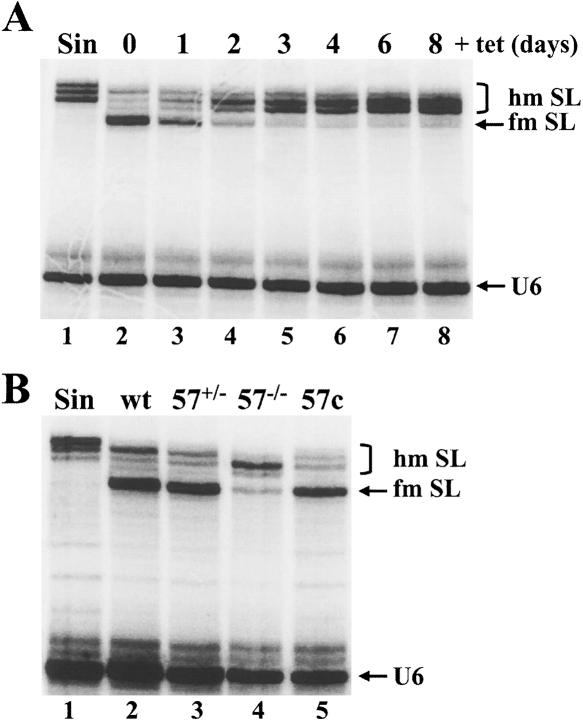

Next, we used primer extension analysis to monitor changes in the SL cap 4 methylation state over a period of 8 d after tet-induction of MT57-RNAi cells (Fig. 3A ▶). As shown previously, at low deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate concentrations a series of characteristic primer extension stops at the 5′ end of the SL are indicative of a fully methylated cap 4 structure (Mandelboim et al. 2002). Specifically, the strong +5 primer extension stop, which is detected in the SL RNA from uninduced MT57-RNAi cells (lane 2), is diagnostic of the presence of N3,2′-O-dimethyluridine at position +4 of the SL RNA, because methylation at N3 of uridine prevents hydrogen bonding with adenosine. Note that the cDNA stops at position +5 of the SL RNA, namely at the nucleotide preceding the modified nucleotide, herein referred to as the +5 primer extension stop. Subsequent primer extension stops are due to ribose 2′-O-methyl modifications. As a control, hypomethylated SL RNA, prepared from cells grown in the presence of the methylation inhibitor sinefungin, allowed primer extension to proceed past position +5 (lane 1) and gave rise to a series of bands characteristic of SL RNA with a partially methylated cap 4. By this analysis MT57-RNAi cells showed a clear defect in cap 4 formation, as early as one day after tet induction (Fig. 3A ▶, lanes 3–8). Most notable was the progressive reduction of the +5 primer extension stop, with the simultaneous appearance of longer extension products suggestive of SL RNA carrying a hypomethylated cap 4.

FIGURE 3.

Ablation of MT57 results in defects in SL RNA modification. (A) The MT57 RNAi cell line was induced with tet for the indicated number of days (lanes 2–8) and total RNA was assayed by primer extension with an SL intron-specific primer. The position of fully modified (fm SL) and hypomodified (hm SL) SL RNA is indicated. RNA isolated from sinefungin-treated cells served as a control for hypomodified SL RNA (lane 1). (B) Primer extension of SL RNA isolated from sinefungin-treated cells (Sin, lane 1), wild-type cells (wt, lane 2), cells carrying one allele of MT57 (57+/−, lane 3), cells deficient of MT57 (57−/−, lane 4), and mt57−/− cells complemented with wild-type MT57 (57c, lane 5). A U6-snRNA-specific primer was included in all the reactions to control for RNA amounts and quality (U6).

To be able to characterize in more detail the role of TbMT57 in the biogenesis of the SL cap 4, we next generated MT57 KO clonal cell lines by homologous recombination with PCR-generated cassettes, encoding either the blastocydin (BSR) or hygromycin (Hyg) resistance genes. Successful ablation of the MT57 locus was confirmed by PCR and by Northern blot analysis (data not shown). Primer extension of the SL RNA from four clonal mt57−/− cell lines, one of which is shown in Figure 3B ▶, lane 4, gave rise to a pattern of extension stops closely resembling that obtained by RNAi down-regulation of TbMT57 (Fig. 3A ▶, lane 4). For most of the SL RNA from mt57−/− cells reverse transcription proceeded beyond position +5, but there was still a detectable amount of a product co-migrating with the +5 primer extension stop characteristic of fully modified SL cap 4. Lastly, to validate that the defect in cap 4 modification was a specific effect of MT57 ablation, we reintroduced a copy of the MT57 gene, tagged at the C terminus with an HA epitope (TbMT57-HA), into mt57−/− cells. Western blot analysis with anti-HA antibodies confirmed expression of the tagged protein (see Fig. 7B ▶, lane 4, below), and primer extension analysis of the SL RNA revealed re-establishment of the +5 primer extension stop to wild type levels, and thus potential restoration of proper modification of the uridine at position 4 (Fig. 3B ▶, lane 5). Taken together, these results indicated a role for TbMT57 in the biogenesis of the SL RNA cap 4 structure. In particular, the strong inhibition of the +5 primer extension stop observed in the SL RNA in induced MT57-RNAi and mt57−/− cells suggested that MT57 functions at a step before or coincident with the methylation of the + 4 uridine to N3,2′-O-dimethyluridine.

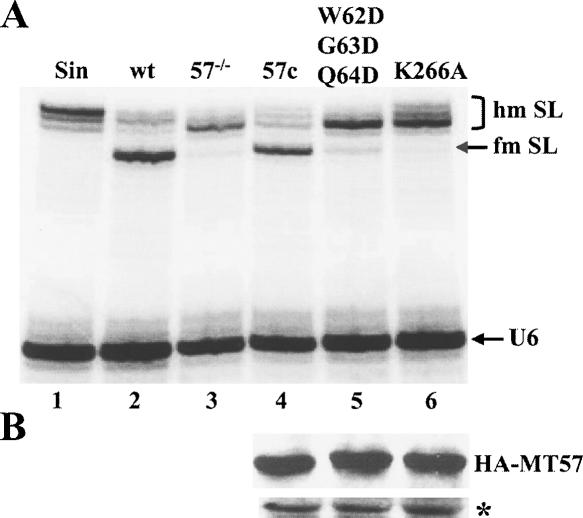

FIGURE 7.

Functional in vivo analysis of MT57. (A) The 5′ end of the SL RNA was analyzed by primer extension in RNA isolated from sinefungin-treated cells (Sin, lane 1), wild-type cells (wt, lane 2), MT57 KO cells (mt57−/−, lane 3), mt57−/− cells complemented with wild-type MT57 (57c, lane 4), mt57−/− cells complemented with the triple MT57 mutation (W62D, G63D, Q64D, referred to as SS1 in the text, lane 5), and mt57−/− cells complemented with MT57 containing the K266A mutation (K266A, lane 6). A U6 snRNA primer extension was included as a control for loading and RNA quality. (B) Western blot of total extracts from complemented mt57−/− cells as described in A with anti-HA antibodies. An immunologically cross-reacting protein was used as a loading control (indicated by an asterisk).

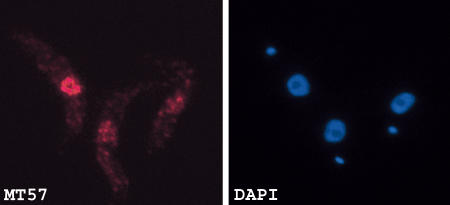

To facilitate the identification of the cellular compartment where TbMT57 accumulates and for future analyses, a Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) tag was introduced by homologous recombination at the carboxy terminus of the sole TbMT57 allele of mt57+/− cells. After establishing a stable cell population, we determined that TAP-tagged TbMT57 was functional since the SL cap 4 was fully modified, as ascertained by primer extension analysis (data not shown). Next, anti-protein A antibodies were used to decorate T. brucei cells expressing TAP-tagged MT57. As shown in Figure 4 ▶, TbMT57 was located predominantly in the trypanosome nucleus with a punctuate distribution.

FIGURE 4.

Cellular localization of TbMT57. Procyclic cells expressing TAP-tagged TbMT57 were processed for indirect immunofluorescence by staining with a rabbit anti-protein A antibody (panel MT57). DNA was stained with DAPI (panel DAPI). The small dot represents the kinetoplast DNA.

2′-O-ribose methylation at position +3 of the SL RNA is severely inhibited in the absence of TbMT57

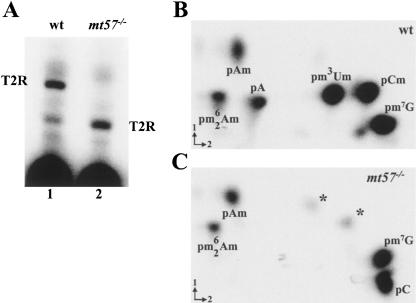

To precisely define the nucleotide composition of the SL cap structure in mt57−/− trypanosomes, we synthesized 32P-labeled RNA in permeabilized wild-type and mt57−/− cells in the presence of all four radiolabelled nucleoside triphosphates and then purified the SL RNA on a sequencing gel. In a first set of experiments we monitored the presence of 2′-O modifications at positions 1–4 of the SL sequence by digesting the RNAs with ribonuclease T2 and separating the products on a 25% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 5A ▶). Due to the inability of ribonuclease T2 to cleave pyrophosphate bonds or 5′ bonds adjacent to 2′-O-modified nucleotides, the fully modified wild-type SL cap 4 is protected from digestion and is revealed as a T2-resistant (T2R) fragment (lane 1). The wild-type T2R fragment was previously shown to correspond to m7GpppAACUAp (Bangs et al. 1992; Ullu and Tschudi 1995). In contrast, a similar analysis with SL RNA isolated from mt57−/− cells (lane 2) gave rise to an abundant T2R fragment with an increased electrophoretic mobility, as compared with that of the wild-type T2R fragment. This observation suggested that the majority of the cap structure of mt57−/−-derived SL RNA was lacking one or more 2′-O methylation. We also noticed that T2 digestion of wild-type SL RNA (lane 1) generated a minor T2R with an electrophoretic mobility similar to that of the T2R fragment of mt57−/− SL RNA (lane 2), but the identity of this fragment was not investigated further.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of the SL cap structure in mt57−/− cells. (A) The SL RNA synthesized in wild type (wt, lane 1) and mt57−/− cells (mt57−/−, lane 2) were gel purified, digested with T2 ribonuclease, and separated on 25% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. T2R indicates the position of the prominent T2-resistant fragment. (B, C) T2-resistant fragments from wild-type (wt, panel B) and mt57−/− cells (mt57−/−, panel C) were digested with nucleotide pyrophosphatase and nuclease P1 and separated on cellulose TLC. The assignment of the various spots was based on previous experiments (Ullu and Tschudi 1995). The identity of three low-abundance spots (one next to pm7G in B and the other two indicated by asterisks in C) has not been investigated.

Next, the T2R fragments from wild-type and mt57−/− SL RNA were purified by DEAE-Sepharose chromatography (see Materials and Methods), further digested to mononucleotides with nucleotide pyrophosphatase and nuclease P1 and separated by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (Fig. 5B,C ▶). Consistent with previously published TLC analyses (Ullu and Tschudi 1995; Mair et al. 2000), the six spots of the wild-type cap 4 structure were identified as pm7G, pm26Am, pAm, pCm, pm3Um, and pA. It is important to point out that, as shown previously (Ullu and Tschudi 1995; Mair et al. 2000), the intensity of the labeled nucleotide spots does not correlate with their representation in the SL cap 4 structure, because of differences in the pools of endogenous ribonucleoside triphosphates present in permeable cells. Within the limits of our analysis the nucleotide composition of the T2R fragment from mt57−/− SL RNA revealed the following differences, when compared with that of the control RNA (cf. panels B and C in Fig. 5 ▶). pA was below the level of detection and the majority of cytidine was present as unmodified pC. We detected two additional low-abundance spots, indicated by asterisks, which did not correspond in relative mobility to either pCm or pm3Um, and whose identity is at present unknown. The above observations were consistent with the presence in mt57−/− SL RNA of a dominant T2R fragment with the sequence 7-methyl-guanosine-ppp-N6,N6,2′-O-trimethyla-denosine-p-2′-O-methyl-adenosine-p-cytosine-p. In conclusion, taking together the results of the T2 digestion and of the TCL analysis, ablation of TbMT57 resulted in severe defects in 2′-O-ribose methylation of the nucleotides encompassing positions +3 and +4 of the SL RNA.

Trans-splicing utilization of the SL RNA is not detectably affected in mt57−/− cells

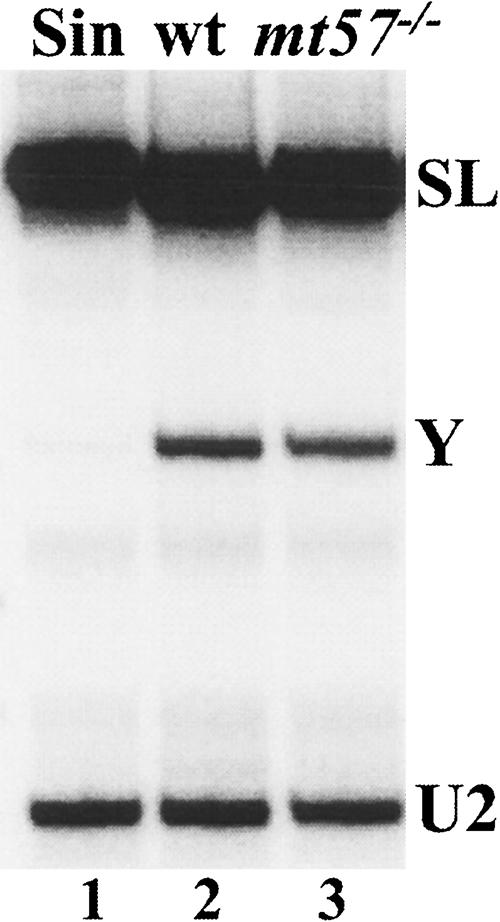

Our results so far have shown that genetic ablation of MT57 is compatible with cell viability and leads to the accumulation of SL RNA with a cap structure defective at positions +3 and +4. Since single nucleotide substitutions at positions +3 or +4 were severely detrimental to trans-splicing utilization of the L. collosoma SL RNA (Mandelboim et al. 2002), we examined trans-splicing activity in mt57−/− cells. To this end we carried out primer extension analysis with an oligonucleotide primer complementary to nucleotides 110–131 of the SL RNA intron (Fig. 6 ▶). In the RNA derived from wild-type cells (lane 2), this assay produced cDNA corresponding to full-length SL RNA, as well as a primer extension stop mapping at the 5′ end of the SL intron. This primer extension stop is mostly diagnostic of Y structures, namely SL RNA intron-pre-mRNA branched intermediates that are formed during the first step of trans-splicing. Whereas incubation with sinefungin, a treatment that blocks trans-splicing in trypanosomes (McNally and Agabian 1992), abolished the detection of Y structures (lane 1), such intermediates were as abundant in mt57−/− RNA (lane 3) as they were in wild-type (lane 2) RNA. We tested four independent clonal mt57−/− cell lines in at least two separate experiments and concluded that within the limits of this assay trans-splicing utilization of hypomethylated SL RNA was not affected at a detectable level. Next, we determined whether the hypomethylated SL sequence from mt57−/− cells was added to mature α-tubulin mRNA (data not shown). The results of this analysis showed that tubulin mRNA from mt57−/− cells carried the hypomethylated cap structure, and that the abundance of α-tubulin mRNA did not change relative to wild-type cells.

FIGURE 6.

Trans-splicing in wild-type (wt) and mt57−/− cells. Primer extension of total RNA with an oligonucleotide complementary to nt 110–131 of the SL RNA. The position of the Y-structure intermediate (Y) and full-length SL RNA (SL) is indicated. An oligonucleotide complementary to the U2 snRNA was included as a loading and quality control (U2).

Functional characterization of TbMT57 in vivo

Despite the relatively low overall sequence conservation between vaccinia virus VP39 and TbMT57, amino acids 3–297 of VP39 aligned with amino acids 17–404 of TbMT57 (see Fig. 1A ▶). This alignment was deemed significant, because a number of key residues important for VP39 function were conserved in the T. brucei protein (indicated by asterisks and filled triangles in Fig. 1A ▶). The alignment also predicted several rather large insertions in TbMT57. Nevertheless, by using SWISS-MODEL TbMT57 could be modeled onto VP39 (Fig. 1B ▶).

With the aid of the existing detailed information about important functional residues in VP39 (Schnierle et al. 1994; Shi et al. 1996), which includes the crystal structure of a ternary complex comprising VP39, m7G-capped RNA and the AdoMet cofactor (Hodel et al. 1998), we predicted key residues in TbMT57, targeted them by mutagenesis and then assayed their effect on cap 4 modification in vivo. Since substitution of residues 37–39 in VP39 (mutation SS1 in ref. Shi et al. 1996) abolished 2′-O methyltransferase activity, we changed the corresponding residues in TbMT57 from WGQ to DDD (residues 62–64, indicated by filled circles in Fig. 1A ▶). Next, since the VP39 mutant AS10, carrying substitutions D138A and R140A, was completely defective in AdoMet binding (Schnierle et al. 1994), we engineered the corresponding substitutions in TbMT57 by changing residues D229 and R231 to alanine. Finally, the predicted catalytic lysine (Li et al. 2004) at position 266 of TbMT57 was mutated to alanine.

The above nucleotide substitutions, namely SS1, AS10 and K266A, were generated by PCR in vitro using as a template the TbMT57-HA gene, which is functional as it restores cap 4 modification in mt57−/− trypanosomes (Fig. 7A ▶, lane 4). Each of the three mutant MT57-HA genes was transfected into mt57−/− cells and, after the establishment of stable cell lines, the expression of the mutant proteins was examined by Western blot with anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 7B ▶). The levels of mutant SS1 (lane 5) and K266A (lane 6) proteins were similar to that of the wild-type TbMT57-HA protein (lane 4). In contrast, the MT57 mutant AS10 was not pursued further, because the protein did not accumulate to a detectable level.

Next, restoration of cap 4 modification was assayed by primer extension (Fig. 7A ▶). As compared to the wild-type TbMT57-HA gene (lane 4) neither the SS1 (lane 5) nor the K266A (lane 6) mutant allele re-established the +5 primer extension stop to wild-type levels. In conclusion, the MT57 SS1 and K266A mutants were defective in the biogenesis of the SL cap 4 structure, thus identifying functional residues in MT57 and validating our predictions based on the VP39 function and crystal structure.

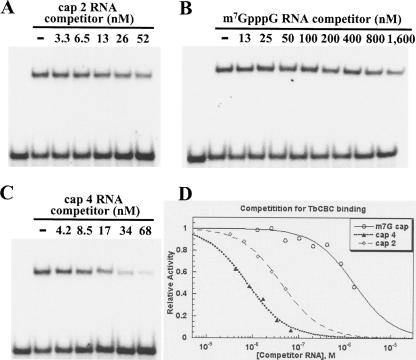

We recently showed that the T. brucei cap binding complex (CBC) can distinguish between a cap 4 and an m7G structure and that it has a much higher affinity for the cap 4 substrate (Li and Tschudi 2005). To further investigate the binding affinity of the CBC to capped RNA and in particular cap 2 RNA, we carried out competitive binding studies. Increasing amounts of m7G-capped RNA, cap 2 RNA, isolated from mt57−/− cells, and cap 4 RNA were mixed with a constant amount of 32P-labeled cap 4 SL RNA substrate, and then a non-saturating amount of affinity purified trypanosome CBC (Li and Tschudi 2005) was added. The reactions were separated on a non-denaturing poly-acrylamide gel (Fig. 8 ▶). Next, we determined the amount of competitor needed to dissociate 50% of the RNP complex (Kd1/2), which was 1.6 μM, 42 nm, and 7.7 nm for m7G, cap 2 and cap 4 RNA, respectively. As shown previously, cap 4 RNA was a highly efficient competitor and we needed to add ~ 200-fold more m7G competitor RNA (Li and Tschudi 2005). Our prediction was that cap 2 RNA will be less efficient than the cap 4 competitor and, indeed, we had to add five and half times more of the cap 2 than cap 4 RNA. Thus, it appeared from our results that the trypanosome CBC has the ability to discriminate between different modification states of the SL RNA.

FIGURE 8.

Inhibition of CBC/SL RNA complex formation by m7G-capped, cap 2, and cap 4 RNA. 5.1 fmol/μL of 32P-labeled cap 4 SL RNA was mixed with increasing amounts of cap 2 SL RNA (A), m7G-capped RNA (B), or cap 4 SL RNA (C). Then, affinity-purified TbCBC (15.0 fmol/μL) was added (Li and Tschudi 2005) and the mixture was processed for non-denaturing gel electrophoresis (Li and Tschudi 2005). The first lane in each gel did not contain CBC. (D) Analysis of the competition titrations for T. brucei CBC with indicated RNA competitors. Data were plotted as the fraction of relative RNP formation with respect to the level with no competitor control. Each set of data was a collection of at least two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In trypanosomatids the SL RNA plays a key role in gene expression by donating its 5′-terminal region to every mRNA through trans-splicing. One of the most remarkable features in the SL RNA is the presence of an elaborate cap 4 structure, consisting of a terminal m7G cap followed by four nucleotides that carry a total of seven methyl groups (Bangs et al. 1992). Since RNA guanylyltransferase and RNA tri-phosphatase components of the trypanosomatid capping apparatus have been identified (Silva et al. 1998; Gong et al. 2003), it is reasonable to postulate that m7G capping of the SL RNA is similar to the capping reaction for mRNAs in yeast and mammalian cells (Shuman 2001). In contrast to the well understood process of m7G cap formation, what remains largely unexplored in any eukaryotic system, with the exception of viruses, is the biogenesis of more complex mRNA cap structures.

Ablation of MT57 results in SL RNA carrying a cap 2 rather than a cap 4 structure

Here, through a combination of bioinformatics, genetics, and biochemical approaches, we present evidence that the trypanosome protein MT57 is involved in the biogenesis of the SL cap 4 structure. First, primer extension analysis revealed that down-regulation by RNAi or genetic ablation of TbMT57 resulted in the appearance of hypomethylated SL RNA, in which the +5 primer extension stop, diagnostic of N3, 2′-O-dimethyluridine, was strongly inhibited. Second, the results of the T2 ribonuclease digestion and TLC analysis indicated that most of the SL RNA from mt57−/− cells carried a cap 2 rather than a cap 4 structure, with the sequence 7-methyl-guanosine-ppp-N6,N6,2′-O-trimethyla-denosine-p-2′-O-methyl-adenosine-p-cytosine. Moreover, the absence of both N3, 2′-O-dimethyluridine and pA (the terminal nucleotide of the wild-type T2R fragment) was consistent with the lack of 2′-O-methylation at the +4 ribose moiety as well. Thus, ablation of MT57 resulted in SL RNA missing two 2′-O-methyl groups on adjacent ribose moieties at positions +3 and +4. The above observations strongly suggest that TbMT57 is a 2′-O-methyltransferase involved in ribose methylation at position +3 and +4 (see below for further discussion). The following line of reasoning also supports our conclusion that TbMT57 functions as a 2′-O-methyltransferase: (1) TbMT57 was identified by database mining by virtue of its similarity to vaccinia virus VP39, a well known mRNA cap-specific 2′-O-methyl-transferase (Barbosa and Moss 1978). The similarity between MT57 and the vaccinia enzyme is strengthened by the presence in MT57 of distinct sequence motifs that in VP39 have been shown to be involved in m7G cap recognition and binding to AdoMet (Fig. 1A ▶). (2) Amino acids 1–404 of MT57 can be modeled using as a reference the crystal structure of VP39 (Fig. 1B ▶). (3) MT57 function in cap 4 modification is affected by mutations of residues, which in VP39 have been shown to be essential for 2′-O-methyltransferase activity (Schnierle et al. 1994; Li et al. 2004).

We also noted that primer extension of the SL RNA in mt57−/− cells revealed a detectable amount of a primer extension stop co-migrating with the +5 primer extension stop diagnostic of N3,2′-O-dimethyluridine. One possibility to explain this observation is that the methyltransferase that adds amethyl group at N3 of the +4 uridine maybe partially active on a substrate devoid of 2′-O-methylations atpositions +3 and +4. Alternatively, the +4 ribose moiety may be methylated only in a subsetof the SLRNA. However, we think this latter possibility is unlikely, because the electrophoretic separation of T2-ribonuclease digestion products of purified mt57−/− SLRNA (Fig. 5A ▶) only generated a major T2R fragment.

What is the role of TbMT57 in cap 4 modification?

By combining the permeable cell labeling method with transcription arrest and direct RNA analyses, we previously showed that in T. brucei permeable cells both the m7G cap and cap 4 modifications are added on nascent SL RNA and thus occur co-transcriptionally (Mair et al. 2000). In light of these findings, the nuclear localization of TbMT57 is not surprising (Fig. 4 ▶). Furthermore, the modifications on the nucleotides corresponding to the SL cap 4 occurred sequentially in a 5′- to 3′-direction, with m7G cap addition and modifications at position +1 and +2 already present on transcripts as short as 67 nt, followed by modifications at positions +3 and +4. In particular, modification at the +3 position to pCm began to appear on transcripts terminating at G111 and preceded the modification of the +4 uridine to N3, 2′-O-dimethyluridine. Thus, it would appear that modifications at positions +3 and +4 can be temporally uncoupled, at least in the permeable cell system. In light of these observations, the findings reported here, namely that both the +3 and +4 positions are affected by the ablation of TbMT57, are compatible with two possibilities. First, TbMT57 may be the methyltransferase for both the +3 and +4 positions. An alternate possibility is that TbMT57 is responsible for 2′-O-methylation at the +3 position, while a different 2′-O-methyltransferase is dedicated to position +4. However, to explain our results this putative +4-specific 2′-O-methyltransferase would require the upstream function of MT57. Thus, in both instances in the absence of TbMT57 both +3 and +4 positions would remain unmodified. At this point, only in vitro studies with recombinant TbMT57 will help clarify this issue, but so far we have not been able to produce recombinant TbMT57 in a soluble form.

Recent work by other laboratories showed that down-regulation in T. brucei of the Sm proteins D1 or E had severe consequences on the SL RNA (Mandelboim et al. 2003; Zeiner et al. 2004). First, the SL RNA was shown to carry a cap 2 structure, as assayed by primer extension. Second, the SL RNA accumulated to high levels and was found in the cytoplasm in a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex of unknown composition. From these and other observations it was suggested that exit to the cytoplasm is the default route for the biogenesis of the mature SL RNP. In this model the SL RNA would acquire a cap 2 structure in the nucleus and then it would be exported to the cytoplasm where it would associate with a complete set of Sm core proteins, be further modified at position +3 and +4, and then be imported into the nucleus. Our results do not lend support to this model in that the primarily nuclear localization of TbMT57 predicts that modification at the +3 position is a nuclear event.

Trans-splicing of cap 2-containing SL RNA

One of the unexpected findings of this study was that SL RNA missing modifications at the +3 and +4 positions was trans-splicing competent. We think this result is compatible with existing evidence and, in particular, with the outcome of the study carried out in the L. collosoma system (Mandelboim et al. 2002). Mutation of the +3 cytosine residue produced severe defects in the L. collosoma SL RNA cap structure and in the accumulation of Y-structure intermediates. In contrast, the +4 SL RNA mutant, although having a defective cap structure, displayed a less severe trans-splicing phenotype. Since mature messenger RNAs carrying the +3 or +4 mutant SL sequence were identified in steady-state RNA, it was clear that the corresponding SL RNA mutants were still utilized in trans-splicing, albeit with reduced efficiencies. Thus, this study indicated that single nucleotide substitutions at the +3 and +4 modification sites were debilitating for SL RNA function but did not completely abolish trans-splicing utilization. In mt57−/− cells we found that the cap 2-containing SL RNA was still competent for trans-splicing and that the extent of accumulation of Y structures was similar to that observed in wild-type cells. Whereas the trans-splicing utilization of the cap 2-containing SL RNA is not in contradiction with the Leptomonas results, the lack of a detectable defect in Y structure accumulation is more difficult to explain. However, one major difference between this and the L. collosoma study is how the assays were carried out. In L. collosoma the trans-splicing utilization of transgenic mutant SL RNAs was assessed using as a reference the utilization of endogenous wild-type SL RNA. In contrast, in mt57−/− cells it was not feasible to ascertain the trans-splicing utilization of cap 2-containing SL RNA in a similar competitive manner, since all the SL RNA was derived from the endogenous gene pool. On the other hand, our failure to detect a trans-splicing defect in mt57−/− cells may be due to the existence, or activation during the long period of selection in culture for mt57−/− cells, of alternate mechanisms to counteract the absence of TbMT57. This is not unprecedented in T. brucei, as we recently reported that down-regulation of MT40, a methyltransferase essential for modification of initiator methionyl-tRNA, is accompanied by overexpression of elongator methionyl-tRNA to compensate for the diminution of the steady-state level of initiator methionyl-tRNA (Arhin et al. 2004). Although we did not detect a defect in the extent of Y structure accumulation in mt57−/− cells, we found that in vitro T. brucei CBC has a lower binding affinity for cap 2 SL RNA relative to the wild-type cap 4 SL RNA. This observation further supports our previous finding that methylation of cap 4 nucleotides contributes to the binding specificity of T. brucei CBC (Li and Tschudi 2005).

VP39, TbMT57, and TbMT48

It was surprising to discover that the T. brucei genome, as well as other trypanosomatid genomes, encodes two proteins, TbMT48 and TbMT57, with striking sequence and predicted structural similarity to the vaccinia virus VP39 protein. In addition to a 2′-O-methyltransferase activity, VP39 also acts in poly(A) tail elongation as the smaller subunit of the heterodimeric vaccinia virus poly(A) polymerase (Schnierle et al. 1992). Whether the trypanosomal proteins have a similar function will require further investigation. While working on this project, we became aware that in 2003 Feder et al. reported on the molecular phylogenetics of ribose 2′-O-methyltransferases and mentioned the identification of two T. brucei DNA fragments encoding partial open reading frames (ORF) with similarity to VP39 (Feder et al. 2003). These partial ORFs correspond to the TbMT57 and TbMT48 genes. Intriguingly, the phylogenetic analysis of Feder et al. groups TbMT57 and TbMT48 with 2′-O-methyltransferases of poxviruses, dsDNA viruses which include vaccinia virus. These authors further suggested that this grouping “ . . . underscores a major role played by intracellular parasites in evolution of new families of RNA modification enzymes.” Our results lend support to this view in that TbMT57 and VP39 are related both in structure and in function as far as the methyltransferase activity is concerned.

Among eukaryotic organisms, for which genomic sequence data are currently available, clear homologs of TbMT57 and TbMT48 genes are only found in trypanosomatid protozoa, suggesting that these proteins function in aspects of RNA metabolism that are unique to this group of organisms. This is the case for TbMT57, which is required for cap 4 biogenesis, but at present we do not know what the substrate for TbMT48 is. Considering that TbMT57 and TbMT48 are closely related, it is likely that the corresponding genes arose by gene duplication in a common ancestor to the trypanosomatid lineage and, with time, their function diversified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bioinformatics

Database searches and multiple sequence alignments were performed at the GenDB Web site (http://www.genedb.org/) and with the T-COFFEE program (Notredame et al. 2000), respectively. Protein structure homology-modeling was done through the SWISS-MODEL server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/).

Plasmids, transfections, and cell lines

To generate the TbMT57 RNAi cell line, a 730 bp fragment (nt 501–1231) of the T. brucei MT57 translated region was assembled as two inverted repeats separated by a stuffer fragment, inserted downstream from a tetracycline (tet)-inducible promoter from the pro-cyclic acidic repetitive protein (PARP) genes (Tschudi et al. 2003) and transformed into strain 29.13.6, expressing the tet repressor and T7 RNA polymerase. A PCR-based method (Shen et al. 2001) was then used to tag one allele of MT57 at the C terminus with the BB2 epitope, and the second allele of MT57 was replaced with the puromycin-resistant gene. We also established a cell line in which TbMT57 was epitope-tagged at the C terminus with a TAP-tag.

RNA analysis

The SL RNA was primer extended with oligonucleotide Y-21, complementary to nt 40–60, except in Figure 6 ▶, where SLIN22, complementary to nt 110–131, was used. U2 and U6 snRNAs were primed with oligonucleotide U2B-17, complementary to nt 46–62, and U6–22, complementary to nt 19–40, respectively.

Procyclic T. brucei YTat1.1 and mt57−/− cells were permeabilized with lysolecithin as described previously (Ullu and Tschudi 1990; Mair et al. 2000). After incubation at 28°C for 15 min, total RNA, radiolabeled with all four nucleotide triphosphates, was extracted with TRIZOL reagent (GibcoBRL) and processed essentially as described (Mair et al. 2000) with the following modifications. After T2 digestion samples were applied to a DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B column equilibrated in 10 mM ammonium formate. The column was washed with 200 mM ammonium formate and step eluted with 600 mM ammonium formate. The eluted RNA was separated on a 25% polyacrylamid–7M urea gel, the T2-resistant fragments were excised, eluted and analyzed by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography.

Other procedures

Processing of cells for double-label indirect immunofluorescence (Ngo et al. 1998), electrophoretic mobility shift assays, and data analysis were done as previously described (Li and Tschudi 2005).

Acknowledgments

We thank Nathalie Chamond for help with immunofluorescence analysis, Jay Bangs for anti-hsp70 antibodies, and Sarah Renzi for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI43594 to C.T. and AI28798 to E.U. from NIAID. G.K.A. was partially supported through a training grant from the NIH (T32 AIO7404).

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2223406.

REFERENCES

- Arhin, G.K., Shen, S., Irmer, H., Ullu, E., and Tschudi, C. 2004. Role of a 300-kilodalton nuclear complex in the maturation of Trypanosoma brucei initiator methionyl-tRNA. Eukaryot. Cell 3: 893–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangs, J.D., Crain, P.F., Hashizume, T., McCloskey, J.A., and Boothroyd, J.C. 1992. Mass spectrometry of mRNA cap 4 from trypanosomatids reveals two novel nucleosides. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 9805–9815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, E. and Moss, B. 1978. mRNA(nucleoside-2′-)-methyltransferase from vaccinia virus. Characteristics and substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 253: 7698–7702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder, M., Pas, J., Wyrwicz, L.S., and Bujnicki, J.M. 2003. Molecular phylogenetics of the RrmJ/fibrillarin superfamily of ribose 2′-Omethyltransferases. Gene 302: 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freistadt, M.S., Cross, G.A., Branch, A.D., and Robertson, H.D. 1987. Direct analysis of the mini-exon donor RNA of Trypanosoma brucei: Detection of a novel cap structure also present in messenger RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 15: 9861–9879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freistadt, M.S., Cross, G.A., and Robertson, H.D. 1988. Discontinuously synthesized mRNA from Trypanosoma brucei contains the highly methylated 5′ cap structure, m7GpppA*A*C(2′-O)mU*A. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 15071–15075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon, P.D. and Moss, B. 1993. Stimulation of poly(A) tail elongation by the VP39 subunit of the vaccinia virus-encoded poly(A) polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 2203–2210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon, P.D., Ahn, B.Y., Garfield, M., and Moss, B. 1991. Poly(A) polymerase and a dissociable polyadenylation stimulatory factor encoded by vaccinia virus. Cell 66: 1269–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong, C., Martins, A., and Shuman, S. 2003. Structure-function analysis of Trypanosoma brucei RNA triphosphatase and evidence for a two-metal mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 50843–50852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Jr., K.A., Crothers, D.M., and Ullu, E. 1995. In vivo structural analysis of spliced-leader RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei and Leptomonas collosoma: A flexible structure that is independent of cap4 methylations. RNA 1: 351–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel, A.E., Gershon, P.D., Shi, X., and Quiocho, F.A. 1996. The 1.85 A structure of vaccinia protein VP39: A bifunctional enzyme that participates in the modification of both mRNA ends. Cell 85: 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel, A.E., Gershon, P.D., Shi, X., Wang, S.M., and Quiocho, F.A. 1997. Specific protein recognition of an mRNA cap through its alkylated base. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4: 350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel, A.E., Gershon, P.D., and Quiocho, F.A. 1998. Structural basis for sequence-nonspecific recognition of 5′-capped mRNA by a cap-modifying enzyme. Mol. Cell 1: 443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. and Tschudi, C. 2005. Novel and essential subunits in the 300- kilodalton nuclear cap binding complex of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 2216–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., Xia, Y., Gao, X., and Gershon, P.D. 2004. Mechanism of RNA 2′-O-methylation: Evidence that the catalytic lysine acts to steer rather than deprotonate the target nucleophile. Biochemistry 43: 5680–5687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.H., Haritan, A., Uliel, S., and Michaeli, S. 2003. trans and cis splicing in trypanosomatids: Mechanism, factors, and regulation. Eukaryot. Cell 2: 830–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair, G., Ullu, E., and Tschudi, C. 2000. Cotranscriptional cap 4 formation on the Trypanosoma brucei spliced-leader RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 28994–28999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelboim, M., Estrano, C.L., Tschudi, C., Ullu, E., and Michaeli, S. 2002. On the role of exon and intron sequences in trans-splicing utilization and cap 4 modification of the trypanosomatid Leptomonas collosoma SL RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 35210–35218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelboim, M., Barth, S., Biton, M., Liang, X.H., and Michaeli, S. 2003. Silencing of Sm proteins in Trypanosoma brucei by RNA interference captured a novel cytoplasmic intermediate in splicedleader RNA biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 51469–51478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally, K.P. and Agabian, N. 1992. Trypanosoma brucei spliced leader RNA methylations are required for trans splicing in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 4844–4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, H., Tschudi, C., Gull, K., and Ullu, E. 1998. Double-stranded RNA induces mRNA degradation in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 14687–14692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, T.W. 2001. Evolutionary origin of SL-addition trans-splicing: Still an enigma. Trends Genet. 17: 678–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame, C., Higgins, D.G., and Heringa, J. 2000. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302: 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, K.L., Watkins, K.P., and Agabian, N. 1987. Trypanosome mRNAs have unusual “cap 4” structures acquired by addition of a spliced leader. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 84: 8190–8194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnierle, B.S., Gershon, P.D., and Moss, B. 1992. Cap-specific mRNA (nucleoside-O2′-)-methyltransferase and poly(A) polymerase stimulatory activities of vaccinia virus are mediated by a single protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89: 2897–2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1994. Mutational analysis of a multifunctional protein, with mRNA 5′ cap-specific (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase and 3′-adenylyltransferase stimulatory activities, encoded by vaccinia virus. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 20700–20706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S., Arhin, G.K., Ullu, E., and Tschudi, C. 2001. In vivo epitope tagging of Trypanosoma brucei genes using a one step PCR-based strategy. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 113: 171–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X., Yao, P., Jose, T., and Gershon, P. 1996. Methyltransferase specific domains within VP-39, a bifunctional protein that participates in the modification of both mRNA ends. RNA 2: 88–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman, S. 2001. Structure, mechanism, and evolution of the mRNA capping apparatus. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 66: 1–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva, E., Ullu, E., Kobayashi, R., and Tschudi, C. 1998. Trypanosome capping enzymes display a novel two-domain structure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 4612–4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschudi, C., Djikeng, A., Shi, H., and Ullu, E. 2003. In vivo analysis of the RNA interference mechanism in Trypanosoma brucei. Methods 30: 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullu, E. and Tschudi, C. 1990. Permeable trypanosome cells as a model system for transcription and trans-splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 3319–3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1991. Trans splicing in trypanosomes requires methylation of the 5′ end of the spliced leader RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88: 10074–10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1995. Accurate modification of the trypanosome spliced leader cap structure in a homologous cell-free system. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 20365–20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiner, G.M., Foldynova, S., Sturm, N.R., Lukes, J., and Campbell, D.A. 2004. SmD1 is required for spliced leader RNA biogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell 3: 241–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]