Abstract

Cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (c-IAP1) can regulate apoptosis through its interaction with downstream TNF receptor effectors (TRAF1 and TRAF2), by binding to and inhibiting certain caspases, and by controlling the levels of specific proapoptotic stimuli (e.g., Smac/DIABLO) within the cell. Studies involving the expression of c-IAP1 mRNA and protein in cells and tissues have provided evidence suggesting c-IAP1 expression may be posttranscriptionally controlled. Because the 5′-UTR of c-IAP1 mRNA is unusually long, contains multiple upstream AUG codons, and has the potential to form thermodynamically stable secondary structures, we investigated the possibility it contained an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that may regulate its expression. In the present study, the c-IAP1 5′-UTR exhibited IRES activity when dicistronic RNA constructs were translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) and in transiently transfected cells. IRES-mediated translation was similar to that exhibited by the hepatitis C virus IRES but varied significantly in RRL and in HeLa, HepG2, and 293T cells, indicating the c-IAP1 IRES was system and cell type specific. IRES-mediated translation was maintained in mono- and dicistronic constructs in which the UTR was inserted downstream from a stable hairpin that prevented cap-dependent ribosome scanning. In cells, the presence or absence of a methylated cap did not significantly affect the translation of polyadenylated, monocistronic RNAs containing the c-IAP1 5′-UTR. IRES-mediated translation was stimulated in transfected cells treated with low doses of pro-apoptotic stimuli (i.e., etoposide and sodium arsenite) that inhibited endogenous cellular translation.

Keywords: translation, apoptosis, internal ribosome entry site, inhibitor of apoptosis protein

INTRODUCTION

Apoptosis is a mechanism by which multicellular organisms can regulate fetal development and tissue homeostasis. It is a means for dispensing of cells in response to cell stress that can include virus infection, the presence of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, chemotherapeutic agents, and UV irradiation. Proapoptotic signals serve to activate a proteolytic cascade of caspases (cysteine proteases), an event that can result in the ultimate death of the cell. Dysfunction of the apoptotic process has been implicated in several neurodegenerative disorders, autoimmune diseases, and the onset of cancer (for comprehensive reviews, see Nicholson 1999; Hengartner 2000; Reed 2000).

Mammalian cells express several inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) that can prevent the onset of cellular apoptosis. To date, eight mammalian IAPs have been identified that include: c-IAP1 (HIAP2, MIHB), c-IAP2 (HIAP1, MIHC), XIAP (ILP-1, MIHA), ILP-2 (Ts-IAP), Livin (ML-IAP, KIAP), NAIP, Survivin (TIAP), and BRUCE (Apollon; LaCasse et al. 1998; Salvesen and Duckett 2002). Members of this family of proteins are characterized by the presence of one or more baculoviral IAP repeat (BIR) motifs, each comprised of an ~70 amino acid residue zinc-binding domain (Hinds et al. 1999). These (BIR) motifs have been demonstrated to be essential for the anti-apoptotic properties of IAPs and can mediate the binding of IAPs to certain caspases (Deveraux et al. 1997; Deveraux and Reed 1999). Several IAPs, including XIAP, c-IAP1, and c-IAP2, also contain a RING domain with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity at the carboxyl terminus of the protein.

C-IAP1 has been demonstrated to suppress cell death by several mechanisms. It has been shown to bind and directly inhibit caspase-3 and -7 and block etoposide-induced processing of caspase-3 (Roy et al. 1997; Ekert et al. 1999). The functionality of c-IAP1 in regulating apoptosis appears to stem from its direct binding and inactivation of caspases and from the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of its RING domain. C-IAP1 can self-ubiquitinate and target itself for proteosome-mediated degradation in thymocytes following treatment with apoptotic stimuli (Yang et al. 2000). Additionally, it was recently demonstrated c-IAP1 could mediate the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of Smac/DIABLO, an inhibitor of IAPs and inducer of apoptosis (Hu and Yang 2003). Also, c-IAP1 forms a heterotrimeric complex with TNF receptor associated factors 1 and 2 (TRAF1 and TRAF2) that can be recruited to tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2; Rothe et al. 1995). After activation of TNFR2, c-IAP1 can mediate the ubiquitination and subsequent removal of TRAF2 (Li et al. 2002). Interestingly, this has been implicated in the sensitization of cells to TNF-α-mediated apoptosis (Wang et al. 1998).

The gene for c-IAP1 is located within chromosome 11 (q22–23; Rajcan-Separovic et al. 1996). Its mRNA (~4.5 kb) is formed from nine exons encoding a protein of approximately 65 kD. It is transcribed from a TATA-less promoter and includes an unusually long (>1.1 kb) 5′-UTR. C-IAP1 is expressed predominantly in fetal lung and kidney and in adult lymphoid tissues (i.e., spleen, thymus, PBLs; Young et al. 1999). The mechanisms controlling c-IAP1 expression during apoptosis are not well characterized, although it has been reported to be transcriptionally controlled by NF-κB induced during TNF-α-mediated apoptosis (Wang et al. 1998). However, the investigation of the expression of c-IAP1 in a panel of human tumor cell lines has provided evidence to suggest that it may also be posttranscriptionally regulated (Tamm et al. 2000). A recent study has demonstrated c-IAP1 protein induction in cells treated with etoposide occurred independently of increases in c-IAP1 mRNA (Ekedahl et al. 2002). Thus, c-IAP1 expression may be both transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally regulated, with the latter potentially involving translational regulation and/or protein stability/turnover.

Translation initiation in the majority of eukaryotic mRNAs is believed to occur via a cap-dependent, ribosome-scanning mechanism (Kozak 2002). This occurs with the 43S preinitiation complex (40S ribosomal subunit, eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAi, and eIF3) being formed at the 5′ end of the mRNA through its association with eIF4F (eIF4E, eIF4G, and eIF4A) where eIF4E serves to bind the m7G cap of the message. The 43S complex scans the template until the initiation codon is recognized. Translation begins following the joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit and the dissociation of some initiation factors (Kozak 1999; Pestova et al. 2001). Translation initiation has become widely recognized as a critical component in the regulation of gene expression. This can be exemplified by the repression of cap-dependent translation that occurs in poliovirus-infected cells. Infection results in proteolytic cleavage of host–cell translation factors (e.g., eIF4G) that abrogate eIF4F-mediated recruitment of the 40S subunit to the majority of capped, cellular mRNAs (Bovee et al. 1998; Gale et al. 2000; Kuyumcu-Martinez et al. 2002; Zamora et al. 2002). Despite this, translation of viral RNA persists (Johannes et al. 1999) due to the cap-independent recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit to an IRES located within the 5′-UTR of the viral RNA (Schmid and Wimmer 1994).

Eukaryotic cells can form transcriptional and posttranscriptional responses to cell stress that can affect various cellular processes. This is observed in the activation of caspases during apoptosis that can cleave several initiation factors, including eIF4G, and inhibit cellular translation (Marissen and Lloyd 1998; Marissen et al. 2000a). Yet, despite this occurrence, a minority of cellular mRNAs can still be translated (Holcik et al. 2000a). One way this has been suggested to occur is by cap-independent translation initiation (e.g., internal ribosome entry; Hellen and Sarnow 2001). VEGF has been reported to be translated during conditions of hypoxia (Stein et al. 1998) and c-myc and PKCδ are translated during apoptosis (Pyronnet et al. 2000; Morrish and Rumsby 2002) via IRES elements within the 5′-UTRs of their mRNAs. Also, the 5′-UTR of XIAP mRNA, an IAP family member, has been demonstrated to contain an IRES (Holcik et al. 1999, 2000b). The 5′-UTRs of these messages are long, contain uAUGs, and have the potential to form GC-rich, stable secondary structures that may obstruct ribosome scanning during cap-dependent translation initiation.

The 5′-UTR of c-IAP1 mRNA possesses features inherent of mRNAs that translate via internal ribosome entry. Because it is unlikely that translation of c-IAP1 mRNA is initiated by canonical cap-dependent mechanisms, the following study was performed to identify potential IRES element(s) in the 5′-UTR of c-IAP1. Additionally, c-IAP1 IRES-mediated translation was tested in cells following treatment with inducers of cell stress.

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of the 5′-UTR of c-IAP1 mRNA

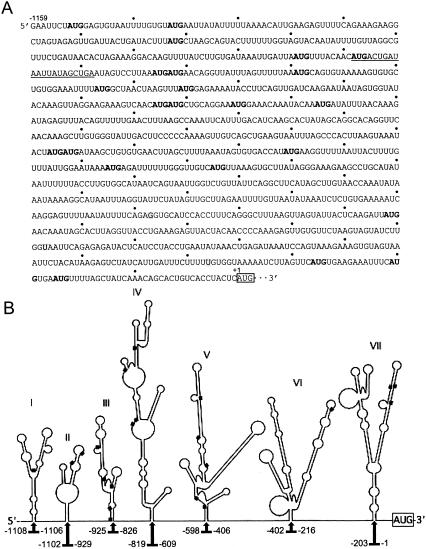

DNA coding for the c-IAP1 5′-UTR was amplified from total cytoplasmic RNA (HeLa) by RT-PCR, sequenced, and compared to the primary nucleotide sequence for human c-IAP1 (GenBank submission NM 001166) shown in Figure 1A ▶. Three nucleotides (shaded in the figure) differed from the published sequence in the region spanning nt −1115 to −1. Further analysis of the sequence revealed 23 upstream AUGs (uAUGs), several of which maintained partial or complete Kozak consensus sequences that could potentially initiate translation of an upstream ORF. The most likely initiation start site and ORF, as predicted by NetStart prediction software, are underlined in the figure. Additionally, the UTR had an average predicted folding energy (ΔG) = −231.8 kcal/mole. The presence of uAUGs as well as RNA structures having folding energies ≤−50 kcal/mole have both been shown to inhibit/abrogate ribosome scanning, which suggests initiation of c-IAP1 mRNA translation might occur by a cap-independent mechanism (e.g., internal ribosome entry). This notion is supported by computer analyses that predicted the UTR contained as many as seven distinct Y-type stem–loop structures (Fig. 1B ▶). Such structural motifs are often detected in RNAs known to initiate translation via internal ribosome entry (Le and Maizel 1997).

FIGURE 1.

Nucleotide sequence and predicted secondary structure of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR. (A) Nucleotide sequences of uAUGs and the iAUG are boldfaced and boxed, respectively. Those nucleotides (−1115 to −1) identified by automated DNA sequencing to be different from the reported sequence (GenBank Accession No. NM_001166) are shaded. A predicted translation initiation site and ORF are underlined. (B) Predicted RNA secondary structure of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR (nt −1115 to −1). The folded structures of individual portions of the UTR were generated using the Web-based Mfold algorithm (ver. 3.1). The overall folding energy (ΔG) for the structure is −231.8 kcal/mole. Domains (I–VII) are comprised of structures that were determined to be the most thermodynamically conserved within the UTR. Note that regions linking these structural domains are not drawn to scale, although the positions of the nucleotides are indicated. The positions of uAUGs are designated by a filled box.

Analysis of c-IAP1 IRES activity in RRL

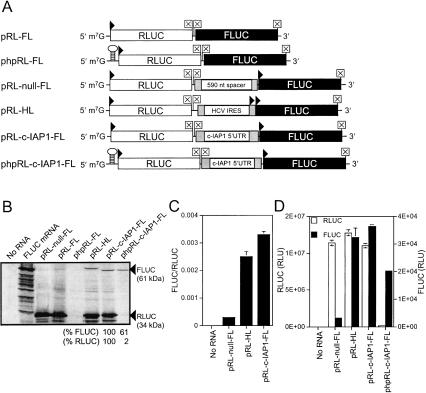

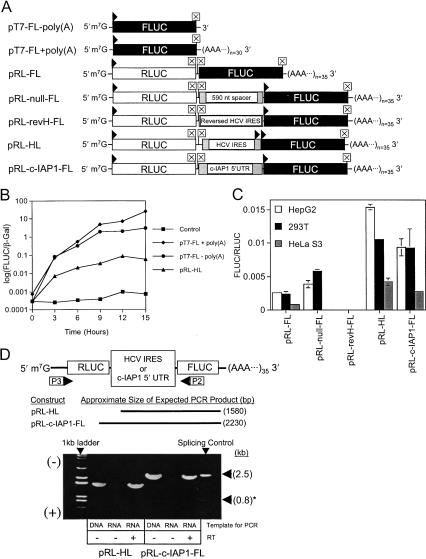

DNA encoding the c-IAP1 5′-UTR was inserted into a dicistronic vector between Renilla (RLUC) and Photinus (firefly; FLUC) luciferase reporter sequences as a test for IRES activity. Capped, runoff transcripts generated in vitro from pRL-null-FL, pRL-FL, phpRL-FL, pRL-HL, pRL-c-IAP1-FL, and phpRL-c-IAP1-FL DNA constructs (Fig. 2A ▶) were translated in nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysates in the presence of 35S-Met, resolved in SDS-PAGE gels, and subjected to autoradiography (Fig. 2B ▶). Because the HCV IRES has been well characterized (Sarnow 2003), pRL-HL RNA served as a positive control for IRES activity. IRES-mediated translation of this RNA initiates at an AUG positioned 22 codons upstream of the FLUC iAUG (Honda et al. 2000) and resulted in a FLUC–fusion protein that had a higher apparent molecular weight than FLUC. PRL-FL RNA, in which the HCV IRES was removed, was initially used as a negative control for IRES activity. However, close inspection of the autoradiogram revealed that low levels of downstream cistron (i.e., FLUC) synthesis occurred from this transcript. This likely resulted from reinitiation of ribosomes that scanned through the intercistronic region (27 nt), for it did not occur when the RNA contained a thermodynamically stable hairpin structure upstream of the RLUC cistron (i.e., phpRL-FL) nor when the intercistronic spacer region was 590 nt in length [(ΔG) = −138.1 kcal/mole (pRL-null-FL)]. Thus, pRL-null-FL was used as a negative control when assessing IRES activity in vitro. Both pRL-c-IAP1-FL and phpRL-c-IAP1-FL RNAs demonstrated the c-IAP1 5′-UTR could initiate FLUC translation irrespective of the presence of a hairpin. Scanning densitometry of the autoradiogram showed insertion of a hairpin resulted in a reduction of cap-dependent translation by ~98% and cap-independent translation by ~40%. FLUC produced from RNA constructs had similar mobilities to that from control mRNA, which indicated translation initiated at similar positions within the transcripts. RLUC and FLUC activities were assayed following translation of dicistronic RNAs in RRLs as a quantitative assessment of c-IAP1 5′-UTR IRES activity. Figure 2C ▶ shows the relative IRES activity (i.e., FLUC/RLUC) of pRL-c-IAP1-FL was higher than the HCV IRES positive control and ~10-fold greater than pRL-null-FL. RLUC and FLUC activities (in relative light units; RLU) for dicistronic RNAs are shown in Figure 2D ▶. Similar RLUC values were observed for pRL-null-FL, pRL-HL, and pRL-c-IAP1-FL samples. Significant FLUC activities were observed for translation reactions that contained equimolar amounts of pRL-HL, pRL-c-IAP1-FL, and phpRL-c-IAP1-FL RNAs compared to that of pRL-null-FL. Furthermore, insertion of a hairpin (phpRL-c-IAP1-FL) inhibited cap-dependent translation of the upstream cistron by ~97% and translation of the downstream FLUC cistron by ~40%, yet FLUC from this template was still sixfold greater than that of the control (see also Fig. 3D ▶). These data were consistent with the gel-scanning data in Figure 2B ▶ and suggest that the c-IAP1 5′-UTR mediates translation of FLUC independently of cap-dependent RLUC translation.

FIGURE 2.

The c-IAP1 5′-UTR mediates internal translation initiation in RRL. (A) Schematic of capped, dicistronic RNAs transcribed from DNA constructs containing a 27-nt spacer (pRL-FL), a 590-nt spacer (pRL-null-FL), a 477-nt spacer containing the HCV IRES (pRL-HL), or the 1115-nt c-IAP1 5′-UTR (pRL-c-IAP1-FL) as intercistronic regions. The dicistronic RNAs included the upstream Renilla luciferase cistron followed by two in-frame stop codons, an intercistronic region, and the downstream firefly luciferase cistron. Also depicted are those transcripts that contained a stable hairpin structure (ΔG = −61 kcal/mole) inserted upstream of the Renilla ORF. The arrowheads and boxed times signs indicate the positions of expected translation initiation and termination, respectively. (B) Autoradiogram of dicistronic RNAs translated in vitro. Samples and their corresponding lanes are indicated at the top of the image. The lane labeled “No RNA” included RRL without the addition of exogenous RNA. Arrows indicate the relative mobilities of Renilla and firefly luciferase proteins. Gel-scanning densitometry was used to approximate FLUC and RLUC protein levels (bottom) for pRL-c-IAP1-FL (set at 100%) and phpRL-c-IAP1-FL so as to assess the effect insertion of a hairpin had on cap-independent FLUC synthesis. The data are the mean values of three individual scans. Additionally, the firefly and Renilla luciferase activities in lysates were determined as detailed in the Materials and Methods. (C,D) Firefly luciferase activity (normalized to Renilla) and firefly luciferase activity plotted together with Renilla luciferase activity, respectively, for the indicated dicistronic RNAs.

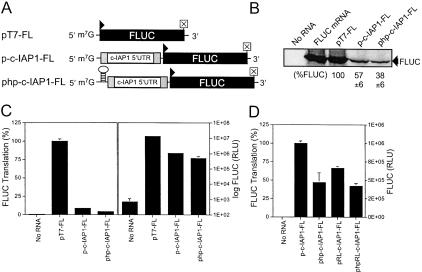

FIGURE 3.

Effect of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR on cap-dependent translation initiation in RRL. (A) Schematic depicting capped, monocistronic test RNAs containing the firefly luciferase reporter preceded by a short leader of arbitrary sequence (pT7-FL), the c-IAP1 5′-UTR (p-c-IAP1-FL), or a thermodynamically stable hairpin followed by the c-IAP1 5′-UTR (php-c-IAP1-FL). (B) Autoradiogram of monocistronic FLUC reporter RNAs translated in vitro. RNAs that were translated are indicated at the top of the figure where “No RNA” indicates RRL incubated without the addition of exogenous RNA. Gel-scanning densitometry was used to approximate FLUC protein levels for pT7-FL (set at 100%), p-c-IAP1-FL, and php-c-IAP1-FL so as to assess what effect the presence of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR and insertion of a hairpin had on FLUC synthesis. FLUC activity in RRL following in vitro translation of monocistronic messages is shown in C and D. (C) Percent FLUC translation from p-c-IAP1-FL and php-c-IAP1-FL messages compared to that of pT7-FL (set at 100%). (D) Percent FLUC translation from php-c-IAP1-FL, pRL-c-IAP1-FL, and phpRL-c-IAP1-FL compared to that of p-c-IAP1-FL (set at 100%) For both C and D, FLUC(RLU) for the samples is indicated to the right.

Monocistronic FLUC reporter constructs containing the c-IAP1 5′-UTR were used to test the effect of the UTR on cap-dependent translation in vitro. Figure 3B ▶ shows both p-c-IAP1-FL and php-cIAP1-FL inhibited, but did not abrogate, cap-dependent FLUC translation. Analysis of FLUC activity in RRL (Fig. 3C ▶) showed the c-IAP1 5′-UTR inhibited translation ~90% (p-c-IAP1-FL) compared to the control (pT7-FL). The presence of a hairpin (php-c-IAP1-FL) inhibited translation an additional ~5%. The panel to the right in Figure 3C ▶ shows the FLUC (RLU) for all monocistronic RNAs was significantly (1 × 103) higher than that of the “No RNA” background. Figure 3D ▶ shows the addition of a hairpin only reduced translation of the monocistronic and dicistronic c-IAP1 constructs 40%–50%. Interestingly, the level of FLUC translation observed for the monocistronic php-c-IAP1-FL RNA was similar to that observed for dicistronic RNAs containing the c-IAP1 5′-UTR regardless of whether a hairpin was included. Most significant was that insertion of a hairpin upstream of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR did not completely abrogate FLUC translation from either dicistronic or monocistronic RNA templates. Collectively, these data suggest the c-IAP1 5′-UTR could inhibit cap-dependent translation and mediate cap-independent translation initiation in vitro.

Analysis of c-IAP1 IRES activity in transiently transfected cells

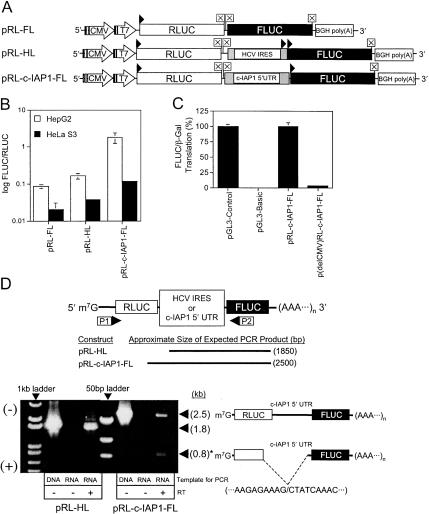

Transient DNA transfections with dicistronic DNA constructs were initially used to analyze c-IAP1 5′-UTR IRES activity in cells. Figure 4B ▶ shows that the c-IAP1 5′-UTR exhibited significant IRES activity compared to the HCV IRES in both HepG2 and HeLa S3 cells. The highest level of relative IRES activity (i.e., FLUC/RLUC) was observed in HepG2 cells and was approximately 10-fold greater than that of the HCV IRES. To test for the possible presence of a cryptic promoter in the c-IAP1 5′-UTR, the CMV promoter was removed from pRL-c-IAP1-FL creating a promoterless construct. This construct produced no significant amount of FLUC in HepG2 cells (Fig. 4C ▶). The structural integrity of the dicistronic RNAs from transfected cells could not be ascertained by Northern blotting (data not shown). Instead, a RT-PCR-based method (Van Eden et al. 2004) revealed the formation of alternatively spliced RNA (indicated by the ~800 bp PCR product “*” in Fig. 4D ▶) in HepG2 cells that had been transfected with the pRL-c-IAP1-FL dicistronic DNA. The PCR products were excised from the gel and sequenced and revealed that alternative splicing removed a portion of the RLUC ORF and most of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR. The resulting transcript coded for an ~87-kD RLUC-FLUC fusion protein. Interestingly, transfection of cells with monocistronic DNAs that contained the c-IAP1 5′-UTR also spliced at the same nucleotide position (data not shown). Conversely, no spliced transcripts were detected following transfection with the HCV dicistronic DNA. Therefore, transfection of DNA constructs could not be used to assess c-IAP1 5′-UTR IRES activity in cells, so transient RNA transfection was used instead.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of IRES activity, promoter activity, and RNA integrity in cells transfected with dicistronic DNA constructs. (A) Schematic of dicistronic DNA test constructs used to transfect cells. RNA synthesis occurs via the CMV strong immediate-early promoter and polyadenylation is initiated by the Bovine Growth Hormone poly(A) signal. (B) HepG2 and HeLa S3 cells were transfected with dicistronic DNA test constructs as detailed in the Materials and Methods. The constructs indicated at the bottom of the figure represent FLUC/RLUC for each cell type. (C) HepG2 cells were transfected with pGL3-control, pGL3-basic, pRL-c-IAP1-FL, and p(ΔCMV)RL-c-IAP1-FL, and the FLUC activity determined. PGL3-basic and p(ΔCMV)RL-c-IAP1-FL lacked SV40 and CMV promoters, respectively. PSV-β-Gal was transfected together with reporter constructs as a control for transfection efficiency. After 20 h, cells were lysed and the FLUC and β-Gal activities in the lysates were determined and plotted as percentages of pGL3-control activity or of pRL-c-IAP1-FL activity (both set at 100%) for both pGL3-basic and p(ΔCMV)RL-c-IAP1-FL, respectively. (D) RT-PCR analysis of HepG2 RNA following transfection (20 h) with pRL-HL and pRL-c-IAP1-FL DNA constructs. The sizes (in base pairs) of DNA fragments expected to be amplified by PCR from template cDNA using primers P1 and P2 are indicated at the bottom of the schematic. DNA amplified by PCR was separated by gel electrophoresis and is depicted in the image of an EtBr-stained 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel. PRL-HL or pRL-c-IAP1-FL DNA served as positive controls and purified RNAs from the transfected HepG2 cells (sans RT) served as negative controls. The positions of both 1-kb and 50-bp DNA ladders are indicated. The schematics of mRNAs serving as templates for RT-PCR (pRL-c-IAP1-FL only) are indicated to the right of the figure. The nucleotide sequence of the splice junction for the smaller transcript is indicated below it.

Figure 5B ▶ shows the results of a kinetic analysis of FLUC expression in 293T cells transfected with either monocistronic (pT7-FL) or dicistronic (pRL-HL) RNAs. FLUC synthesis from capped, polyadenylated [except pT7-FL (−)poly(A)] transcripts was assayed over a period of 15 h. FLUC synthesis was observed to plateau from 9 to 12 h for monocistronic and dicistronic RNAs. The presence of a 35-nt poly(A) tail [pT7-FL (+)poly(A)] correlated with an ~2.5-fold increase in FLUC synthesis at 9 h when compared to the nonpolyadenylated [pT7-FL (−)poly(A)] template. The presence or absence of a poly(A) tail did not significantly affect the time at which FLUC synthesis plateaued. Thus, in further experiments, luciferase activities in cells were assayed 8 h following transfection with capped, polyadenylated RNAs.

FIGURE 5.

The c-IAP1 5′-UTR mediates internal translation initiation in cells transfected with capped, polyadenylated dicistronic RNA constructs. (A) Schematic of capped RNAs transcribed in vitro and used in transient transfection of HepG2, 293T, and HeLa S3 cells. The presence/absence of a poly(A) tail as well as its length is as indicated. (B) Time course (15 h) of firefly luciferase expression in 293T cells after transfection with exogenous RNAs. Cells were cotransfected with equimolar amounts of capped, runoff RNA transcripts (indicated in the figure key) and pSV-β-Gal as described in Materials and Methods. Unlike pT7-FL, both pT7-FL +poly(A) and pRL-HL RNAs contained a poly(A) tail transcribed from the vector sequence. Cells transfected with pSV-β-Gal alone served as the negative control for the experiment. FLUC and β-Gal activities were determined in cell lysates at 3-h intervals following the initial transfection. Data are the average values of two measurements from a single experiment and are plotted as (FLUC/β-Gal) as a function of time. (C) HepG2, 293T, and HeLa S3 cells were transiently transfected with capped, polyadenylated dicistronic RNA constructs. Cells were lysed approximately 8 h following transfection and the RLUC and FLUC activities determined. The constructs indicated at the bottom of the figure represent FLUC/RLUC for each cell type. (D) RT-PCR analysis of 293T RNA following transfection (8 h) with pRL-HL and pRL-c-IAP1-FL RNA constructs. The sizes (in base pairs) of DNA fragments expected to be amplified by PCR from template cDNA using primers P3 and P2 (P1 and P2 for “Slicing Control”) are indicated at the bottom of the schematic. DNA amplified by PCR was separated by gel electrophoresis and is depicted in the image of an EtBr-stained 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel. PRL-HL or pRL-c-IAP1-FL DNA served as positive controls, and purified RNAs from the transfected 293T cells (sans RT) served as negative controls. The positions of both a 1-kb DNA ladder and the splice products (i.e., Splicing Control) from Figure 4D ▶ are indicated.

Figure 5C ▶ shows the relative IRES activity (i.e., FLUC/RLUC) in HepG2, 293T, and HeLa S3 cells following transfection with dicistronic RNAs. PRL-FL, pRL-null-FL, and pRL-revH-FL [(ΔG) = −181.8 kcal/mole] RNAs served as negative controls for IRES activity. Interestingly, these constructs exhibited different levels of FLUC/RLUC in all cell types tested. In the case of pRL-null-FL (HeLa S3 only) and pRL-revH-FL (all cell types), no significant amount of FLUC could be detected and the FLUC/RLUC values were zero relative to background. In contrast, pRL-HL and pRL-c-IAP1-FL RNAs exhibited significant IRES activity compared to controls in all cell lines tested. The IRES activity of pRL-HL was statistically no different than that of pRL-c-IAP1-FL in 293T cells. However, the IRES activity of pRL-c-IAP1-FL was ~60% that of pRL-HL in both HepG2 and HeLa S3 cells. The IRES activity of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR was highest in HepG2 and 293T cells and lowest in HeLa S3 cells when tested as a dicistronic RNA construct. It is important to note that FLUC/RLUC values varied between experiments, likely due to the efficiency of capping of in vitro transcripts; however, fold-stimulation compared to negative controls typically remained constant (Van Eden et al. 2004). For this reason, FLUC/RLUC values from DNA and RNA transfections cannot be directly compared. Additionally, no RNA splicing was detected by RT-PCR following transfection with capped, polyadenylated pRL-c-IAP1-FL RNA (Fig. 5D ▶).

To address the effect of the UTR on cap-dependent translation, cells were transfected with capped, polyadenylated monocistronic RNAs (Fig. 6A ▶) containing the FLUC reporter preceded either by a short leader of arbitrary sequence or by the c-IAP1 5′-UTR. Also, both RNAs were compared on the basis of either having or lacking a m7G cap (Fig. 6B ▶). Comparison of FLUC activities in cells transfected with pT7-FL (+)cap and p-c-IAP1-FL (+)cap RNAs demonstrated the presence of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR significantly inhibited FLUC synthesis. The extent of inhibition was observed to be cell-type specific. The highest levels of inhibition (~90%) were in HepG2 and HeLa S3 cells, whereas in 293T cells FLUC synthesis was inhibited ~60%. Transfection of cells with pT7-FL (+/−) cap RNAs demonstrated the absence of a cap inhibited FLUC synthesis by ~98% in all cell types. Conversely, transfection of cells with p-c-IAP1-FL (+/−)cap RNAs showed the absence of a cap did not correlate with a reduction in FLUC synthesis. In fact, FLUC activities were the same in HeLa S3 cells transfected with p-c-IAP1-FL RNAs regardless of the presence of a cap, and in HepG2 they were higher for RNA lacking a cap.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR on cap-dependent translation initiation in cells cotransfected with monocistronic RNA test constructs and pSV-β-Gal. (A) Schematic of polyadenylated, monocistronic RNAs transcribed in vitro and used to transfect cells. The presence/absence of a m7G cap structure is as indicated. (B) FLUC/β-Gal activities were determined for HepG2, 293T, and HeLa S3 cell lysates after transfection with pT7-FL and p-c-IAP1-FL monocistronic RNAs either having or lacking a cap. All RNAs contained a poly(A) tail and were transfected as detailed in the Materials and Methods. (C, top panel) Autoradiogram of a nylon membrane showing stability of [α-32P]CTP-labeled capped and noncapped pT7-FL and p-c-IAP1-FL polyadenylated RNAs in transfected 293T cells. Lower panel shows the methylene blue stain of ribosomal RNAs (28S rRNA) on the same membrane that was used as a loading control.

Figure 6C ▶ shows the effect of capping on the stability of polyadenylated pT7-FL and p-c-IAP1-FL RNAs in transfected 293T cells. Over the span of the assay (4 h), radiolabeled capped and noncapped polyadenylated RNAs appeared to be equally stable. These data were consistent with those of a previous study that showed the stabilities of capped and uncapped polyadenylated RNAs to be equivalent in transfected cells (Wang and Kiledjian 2001). Collectively, these data, like those in vitro, suggest the c-IAP1 5′-UTR can inhibit cap-dependent translation and mediate cap-independent translation initiation.

Effect of cellular stress on c-IAP1 IRES activity

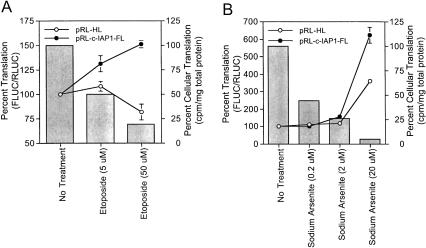

Previous studies have demonstrated the UTRs of some mRNAs may regulate translation initiation during times of cellular stress and other instances where cap-dependent translation is down-regulated (e.g., cell division; Hellen and Sarnow 2001). Thus, it is possible the IRES activity of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR is regulated during cellular stress. In support of this, posttranscriptional induction of c-IAP1 synthesis has been reported in non-small-cell carcinoma cells following etoposide treatment (Ekedahl et al. 2002). To test if c-IAP1 IRES activity is stimulated during cell stress, 293T cells were treated with different doses of etoposide or sodium arsenite, then transiently transfected with capped, polyadenylated pRL-c-IAP1-FL or pRL-HL dicistronic RNAs. Approximately 8 h following transfection, the changes in IRES activity versus that of the control (i.e., no treatment) were determined for each etoposide and sodium arsenite treatment (line graphs in Fig. 7 ▶, A and B, respectively). Concomitant increases in c-IAP1 IRES activity occurred with increasing concentrations of etoposide and sodium arsenite. Stimulation of IRES activity was maximal at the highest concentration of each treatment and was approximately 1.5-fold and 6.5-fold greater than the control with 50 μM etoposide and 20 μM sodium arsenite treatments, respectively. Stress-mediated stimulation of c-IAP1 IRES activity was consistently greater than that of the HCV IRES (pRL-HL), which actually decreased following etoposide treatment.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of apoptosis-inducing agents on the IRES activity of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR in transfected cells. 293T cells were treated 15 h prior to and during RNA transfection with increasing concentrations of etoposide (A) or sodium arsenite (B) as indicated in the figure. Treated cells were transiently transfected with capped, polyadenylated pRL-c-IAP-1-FL or pRL-HL dicistronic RNAs. Approximately 8 h after transfection, FLUC and RLUC luciferase activities were determined for each treatment and plotted as percent change in FLUC/RLUC compared to the control set at 100% (i.e., No Treatment; line graphs). Alternatively, the affect of each treatment on endogenous mRNA translation in 293T cells was determined by metabolically labeling cellular protein approximately 7.5 h after transfection as detailed in the Materials and Methods. The effect of each treatment on TCA-precipitable 35S-label cpm/mg total protein is compared to the control set at 100% (i.e., No Treatment; bar graphs). In this case, data are the average values of an experiment performed in duplicate.

The effect of stress agent addition on endogenous cellular translation varied and is given as bar graphs in Figure 7 ▶, A and B. Treatment with etoposide and sodium arsenite resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of endogenous cellular translation. Greater than 80% inhibition of cap-dependent translation was achieved with 50 μM etoposide and 20 μM sodium arsenite treatments, which cause cleavage of eIF4GI and eIF2α at these concentrations (Marissen and Lloyd 1998; Marissen et al. 2000b). Interestingly, the highest levels of c-IAP1 IRES stimulation correlated with treatments where endogenous cellular translation was most severely inhibited. Collectively, these data suggest the IRES activity of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR could be stimulated during inhibition of endogenous mRNA translation in cells following treatment with etoposide and sodium arsenite.

DISCUSSION

The c-IAP1 gene has been demonstrated to be a target for NF-κB transcriptional activity in human fibrosarcoma cells following TNF-α-induced apoptosis (Wang et al. 1998). Also, studies investigating the expression of c-IAP1 mRNA and protein in both cells and tissues have demonstrated c-IAP1 expression may also be posttranscriptionally controlled (Tamm et al. 2000; Ekedahl et al. 2002). A recent report demonstrated 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 and laminar fluid shear stress could induce c-IAP1 protein expression in vascular endothelial cells without affecting the intracellular levels of its mRNA (Taba et al. 2003). This was attributed to both treatments inhibiting the proteosome-mediated degradation of c-IAP1. The results of the present study provide evidence that c-IAP1 expression can also be regulated at the initiation stage of translation via an IRES located within the 5′-UTR of its mRNA.

Here we demonstrate that dicistronic RNA test constructs containing the c-IAP1 5′-UTR exhibited IRES activity in both rabbit reticulocyte lysates and in transiently transfected cells. IRES activity in RRL was slightly higher than that of the HCV IRES and was not blocked by the insertion of a stable hairpin structure upstream of the Renilla cistron. The use of monocistronic test RNAs demonstrated that insertion of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR inhibited cap-dependent translation in vitro. Transfection of cells with dicistronic test RNAs demonstrated c-IAP1 5′-UTR IRES activity to be cell-type specific. No aberrant RNAs could be detected in cells using this method of transfection. Consistent with the data obtained in RRL, transfection of cells with monocistronic test RNAs also demonstrated the c-IAP1 5′-UTR could inhibit cap-dependent translation in vivo. The levels of inhibition were found to vary according to cell type. Also, in cells, the presence or absence of a m7G cap did not significantly affect the translation of a polyadenylated, monocistronic FLUC reporter that was preceded by the c-IAP1 5′-UTR. Thus, the c-IAP1 5′UTR could mediate the initiation of cap-independent translation in vivo. Finally, the IRES activity of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR was found to fluctuate in transfected cells pretreated with inducers of cell stress. IRES stimulation occurred in cells pretreated with pro-apoptotic stimuli that resulted in a concurrent inhibition of cap-dependent translation. The findings presented here suggest intracellular c-IAP1 expression can be regulated posttranscriptionally during the initiation step of translation via an IRES that can be stimulated during cell stress and times of cap-dependent translation shutoff.

The insertion of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR upstream of a monocistronic FLUC reporter inhibited cap-dependent translation in RRL and in cells. This is consistent with the observation that only low levels of c-IAP1 protein are detected in normal tissues (Young et al. 1999) and supports the notion that inefficient or low levels of translation are necessary for certain mRNAs that encode proto-oncogenes as well as growth factors, cytokines, receptors, and transcription factors (Kozak 1991). These factors require stringent control of their expression to ensure correct protein levels at specific times and locations within the cell. The insertion of a stable RNA hairpin upstream of the c-IAP1 5′-UTR (i.e., php-c-IAP1-FL) resulted in an additional ~50% reduction in translation in RRL, which suggests that approximately equal contributions were made to translation by conventional cap-dependent ribosome scanning and internal ribosome entry in vitro. Also, scanning did not contribute to IRES-mediated translation of the downstream cistron from dicistronic test RNAs. However, in cells transfected with monocistronic, polyadenylated c-IAP1 RNAs, the presence of a cap did not correlate with translation efficiency. In HeLa S3 cells, uncapped c-IAP1 RNA translated as efficiently as capped, and in HepG2 cells, it was translated more efficiently. This suggests both capped and uncapped RNAs were translated at low levels in vivo primarily via a cap-independent mechanism (i.e., internal ribosome entry). Thus, initiation by ribosome shunting (Ryabova and Hohn 2000) was unlikely because translation of monocistronic c-IAP1 RNA was largely cap independent; however, it is possible shunting or another method of ribosomal translocation may have occurred following internal ribosome entry.

The c-IAP1 5′-UTR displayed IRES activity both in vitro and in transfected cells, but, like the HCV IRES, activity was low in RRL. This suggests cellular factors, or trans-activating factors, may be required for the c-IAP1 5′-UTR to sustain efficient IRES activity. In fact, there are at least several cellular trans-activating factors that have been identified in studies involving IRES-mediated translation of viral mRNAs including La autoantigen (Meerovitch et al. 1993), poly(C) binding protein (PCBP; Blyn et al. 1997), and polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PTB; Hellen et al. 1993). Both La and PTB have been demonstrated to enhance HCV IRES-mediated translation in reticulocyte lysates (Ali and Siddiqui 1995; Pudi et al. 2003). Also, it has been proposed that heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins C1 and C2 (hnRNPC1 and -C2) are part of a RNP complex that forms on the XIAP IRES, which together with La facilitates XIAP IRES-mediated translation (Holcik and Korneluk 2000; Holcik et al. 2003).

Recently, the notion of IRES-mediated translation in eukaryotes has been challenged on the basis of the methods typically used for the identification of IRES elements in cellular mRNAs (Kozak 2001). It was proposed that IRES activity in cells transiently transfected with dicistronic DNA test constructs may result from aberrant RNA cleavage, RNA splicing, and/or from the presence of a cryptic promoter within the DNA construct itself. This could contribute to the formation of low amounts of monocistronic message that might be translated via conventional scanning mechanisms. Therefore, we included tests for cryptic promoters, RNA splicing, and assayed translation of RNA transfected directly into cells. Our assays indicated cryptic promoter activity was absent, but the c-IAP1 5′-UTR did promote inefficient splicing. Therefore, all assays for IRES activity in cells were performed by RNA rather than DNA transfection.

Apoptosis is a process characterized by an ordered sequence of both morphological and biochemical changes that can result in cell death. These changes include alterations to components of the translation machinery that can result in a shutdown of endogenous cellular translation. Here, endogenous cellular translation was inhibited in 293T cells following treatment with low doses of etoposide, a genotoxic agent, and sodium arsenite, an inducer of oxidative cell stress. The most significant stimulation in c-IAP1 IRES activity occurred following treatment with 50 μM etoposide and 20 μM sodium arsenite. Similar levels of stimulation have been reported for c-IAP1 protein induction in cells following low dose γ irradiation and etoposide treatments (Ekedahl et al. 2002) and XIAP protein induction in cells following treatment with serum starvation or low dose γ irradiation (Holcik et al. 1999), where the amounts of mRNA dropped or remained unchanged, respectively. The c-IAP1 IRES appeared to be specifically up-regulated in cells following treatment with several pro-apoptotic stimuli, for IRES activity did not change in response to treatments resulting in increased levels of cap-dependent translation (i.e., EGF; data not shown). Collectively, these results implicate c-IAP1 IRES-mediated translation in the regulation of cell survival during conditions of cell stress. This supports the notion that IRES-mediated translation during apoptosis might be a process by which the ultimate fate of the cell is controlled (Holcik et al. 2000a).

To understand the mechanisms involved in the regulation of c-IAP1 IRES-mediated translation during cellular stress it will be essential to correlate its activation with the posttranslational modifications that occur to cellular translation factors. For example, poliovirus infection of permissive cells results in the cleavage of eIF4G by viral 2A proteinase that removes the eIF4E-binding domain and abrogates cap-dependent translation. Yet, IRES-mediated translation of picornavirus mRNA still occurs through the binding of truncated eIF4G, eIF4B, and the recruitment of 40S ribosomal subunits (Hambidge and Sarnow 1992; Ochs et al. 2002). Also, it has been demonstrated that activation of both Apaf-1 and DAP5 IRES elements during apoptosis is caspase-3 dependent and mediated by the proteolytically cleaved forms of eIF4G and DAP5 (i.e., eIF4G(p76) and DAP5(p86), respectively; Henis-Korenblit et al. 2002). Work is in progress to ascertain what translation factor modification(s) regulate c-IAP1 IRES-mediated translation in cells. It is possible that additional factors involved in the control of cellular apoptosis are similarly regulated by IRES elements within their mRNAs, the identification and characterization of which should broaden our understanding of the onset and progression of apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Etoposide [4′-Desmethylepipodophyllotoxin 9-(4,6-O-ethylidene-β-D-glucopyranoside)] and sodium arsenite were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. M7G(5′)ppp(5′)G cap analog was from Ambion. [35S]methionine-cysteine (Tran35S-label) and [α-32P]CTP was from ICN Biomedicals, Inc. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Hyclone Laboratories. Restriction endonucleases and the pSV-β-Gal, pGL3-Control, and pGL3-Basic vectors were from Promega Corp. Oligonucleotide DNA primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. Unless stated otherwise, all other compounds were reagent-grade and obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Construction of dicistronic and monocistronic reporter constructs

The pRL-HL dicistronic vector was the kind gift of Dr. S.M. Lemon (University of Texas Medical Branch) and its design and construction have been previously described (Honda et al. 2000). RNA transcribed from this vector contain an upstream cistron coding for Renilla luciferase and a downstream cistron coding for firefly luciferase with intervening sequence containing the HCV IRES. Translation of the upstream cistron (i.e., Renilla luciferase) is via canonical, cap-dependent mechanisms, whereas translation of the downstream cistron (i.e., firefly luciferase) occurs cap independently by internal ribosome entry. The primary nucleotide sequence of pRL-HL was mutated (QuickChange protocol; Stratagene) so as to incorporate a novel SacII restriction enzyme site 17 nt upstream of the firefly luciferase start codon. This resulted in the intercistronic region being flanked by NotI and SacII sites, which were utilized in the construction of dicistronic constructs. The pRL-HL plasmid was digested with NotI and SacII, treated with T4 DNA polymerase, and blunt-end ligated to generate the pRL-FL construct. The pRL-null-FL construct was obtained by inserting a 590-nt region of DNA coding for human PKR into pRL-HL. The pRL-revH-FL construct was obtained by inserting the HCV IRES in reversed orientation into pRL-HL. A 1.1-kb DNA fragment corresponding to the region within the 5′-UTR of c-IAP1 (GenBank accession number: NM_001166) just upstream of the reported c-IAP1 ORF was amplified from total cytoplasmic RNA (HeLa) by RT-PCR using primers 5′-ctagcggccgcacattgaaga gttttcagaaagaaggc-3′ (sense) and 5′-cagccgcgggagtaggtgacagtgctgttt gatagc-3′ (antisense; NotI and SacII are underlined). The product was ligated into pGEM-T (Promega), sequenced, and subsequently cloned into pRL-HL at NotI and SacII sites to produce pRL-c-IAP1-FL. DNA amplified by long-range PCR from pRL-c-IAP1-FL excluding the upstream Renilla ORF was blunt-end ligated to create the p-c-IAP-1-FL monocistronic construct. To eliminate the possibility of cap-dependent, ribosomal read-through of dicistronic and monocistronic RNAs, a stable hairpin (5′-ccccgcgcacc accgccgacgtcggcggtggtgcgcgggg-3′, predicted ΔG = −61 kcal/mole; Chen et al. 1995) was inserted upstream of reporter coding sequences to create the plasmid vectors phpRL-FL, phpRL-c-IAP1-FL, and php-c-IAP1-FL. DNA amplified by long-range PCR from pRL-c-IAP1-FL, so as to exclude the CMV promoter, was blunt-end ligated to create the p(ΔCMV)RL-c-IAP1-FL construct. Additionally, constructs used for transient RNA transfection contained a synthetic 35-nt poly(A) sequence directly inserted 12 nt downstream from the firefly luciferase ORF. All constructs were verified by restriction enzyme analysis and automated DNA sequencing, the latter as a service provided by Lone Star Laboratories.

In vitro transcription and translation

Plasmid DNA was linearized prior to transcription using XhoI (pRL-HL, pRL-null-FL, pRL-c-IAP1-FL, phpRL-c-IAP1-FL, p-c-IAP1-FL, php-c-IAP1-FL), BamHI (pRL-FL, pT7-FL), or SacI (phpRL-FL). Capped, runoff RNA transcripts were synthesized using recombinant T7 RNA polymerase as previously described (Byrd et al. 2002). Following transcription in vitro, NucAway spin columns (Ambion) were used to separate nonincorporated nucleotides. RNA integrity was assessed by glyoxol/DMSO-agarose gel electrophoresis and the concentration of RNA estimated by UV spectroscopy. Nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL; Promega) were programmed with RNA transcripts (~80 pmole/mL) in the presence of [35S]methionine-cysteine for 90 min at 30°C in accordance with the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. Translation reactions were analyzed by autoradiography of SDS-PAGE gels (12.5% [w/v] acrylamide) using Biomax MR film (Eastman Kodak, Co.). Additionally, 2 μL from translation reactions (diluted 1:20 in PBS) were analyzed for FLUC and RLUC activity.

Cell culture and transient DNA/RNA transfection

Human cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. HeLa S3 cervical adenocarcinoma cells and 293T embryonic kidney cells were passaged as monolayer cultures in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 U penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells were grown in Eagle’s medium supplemented as described above. All cultures were grown in a humidified incubator at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Transient DNA transfections were performed using LipofectAMINE and Plus reagents (Invitrogen) according to the specifications of the manufacturer. Briefly, 4 × 104 cells were seeded per well of a 24-well plate 15 h prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with DNA (0.5 μg/well) and cultured at 37°C for an additional 20 h then harvested by removing the medium and lysing the cells in Passive Lysis Buffer (PLB; Promega).

Alternatively, cells were transfected with RNA. Plasmid constructs were linearized with AgeI (XhoI for pRL-HL, HpaI for pT7-FL) so all runoff RNA transcripts would contain a poly(A) tail. Capped, poly(A) runoff RNA transcripts were generated in vitro using recombinant T7 RNA Polymerase. NucAway spin columns (Ambion) were used to separate nonincorporated nucleotides following treatment of the RNA with DNAse I and phenol: chloroform (1:1). RNA integrity was assessed by glyoxal/DMSO-agarose gel electrophoresis and the concentration of RNA estimated by UV spectroscopy. Transient RNA transfections were performed using DMRIE-C (Invitrogen) according to the specifications of the manufacturer. Approximately 3 × 105 cells were seeded per well of a 12-well plate 18 h prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with RNA (3–5 μg/well), then cultured at 37°C for approximately 8 h prior to removing the medium and lysing the cells in PLB. Incubation of cells with etoposide and sodium arsenite preceded (~15 h) and was continued during transfection.

Transfection efficiencies were assessed by transfecting cells with pEGFP and determining the ratio of fluorescent-positive cells to fluorescent-negative cells using an Olympus IX70 fluorescent microscope (Olympus Instruments). When appropriate, pSV-β-Gal DNA was cotransfected with DNA or RNA reporter constructs as a control for transfection efficiency.

Metabolic labeling of proteins

Following treatment with apoptosis-inducing agents (as specified in the figure legends), transfected cells were pulse-labeled with 10 μCi [35S]methionine-cysteine in methionine-cysteine depleted medium (1 mL/well) 30 min prior to harvesting. Cells were washed twice in PBS, then separated for protein analyses. Total cellular protein was determined using the Bradford Assay. 35S-labeled protein was determined following scintillation counting of TCA-precipitable label. Cellular translation shutoff in Figure 7 ▶ is the percent decrease in TCA-precipitable label (in cpm/mg total protein) as compared to the “no treatment” control set at 100%.

Luciferase and β-galactosidase assays

RLUC and FLUC activities were quantitated using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter System (Promega) and a Sirius luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems). Typically, 5–20 μL cell lysate (posttransfection) was combined sequentially with firefly then Renilla luciferase-specific substrates (i.e., beetle luciferin and coelenterazine, respectively) according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. Light emission was measured 3 sec after addition of each of the substrates and integrated over a 10-sec interval.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined using the Galacto-Light Chemiluminescent Assay System (Applied Biosystems) and luminometer according to the specifications of the manufacturer. Light emission was measured 2 sec after addition of each of the substrates and integrated over a 1-sec interval. Unless stated otherwise, luciferase and β-galactosidase data are given as the averages ±SD of at least three individual experiments.

RNA analyses

RNA secondary structure predictions were computed using the Web-based Mfold algorithm (ver. 3.1) at http://www.bioinfo.rpi.edu/applications/mfold/old/rna/form1.cgi. The UTRscan program was used to identify conserved structural elements in the c-IAP1 5′-UTR versus those of other mRNAs known to contain IRES elements. Translation start predictions were made using NetStart (ver. 1.0).

Cytoplasmic RNA for RT-PCR analysis was isolated from cells using TriZol reagent (Sigma) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. RT-PCR was performed as a test for mRNA splicing in cells following DNA/RNA transfection. After DNAse I treatment (DNA transfection only), 1 μg of purified cellular RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using the ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System (Promega) and an oligo-d(T)12–18 primer. PCR was used to amplify intercistronic regions of dicistronic cDNAs using combinations of the primers P1 5′-gctaacgcagtcagtgcttctgacac-3′ (sense), P2 5′-tctcttcatagccttatgcagttgc-3′ (antisense), P3 5′-gctagccaccatgacttcgaaag-3′ (sense; see figure legends for details).

Capped and noncapped polyadenylated RNAs were radiolabeled with 32P-CTP (~2 μCi/100 μL) during in vitro, runoff transcription with T7 RNA polymerase and were used to assess concentration, integrity, and stability of transcripts following transfection into cells. Stability of radiolabeled RNAs in transfected 293T cells was determined by harvesting cells at specific times and extracting the RNA immediately into TriZol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA samples were then denatured in glyoxal/DMSO, separated in a 1% (w/v) agarose gel, and transferred to a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Autoradiography was performed for 6 h at −80°C using Kodak X-OMAT AR imaging film. For each of the samples, the 28S ribosomal subunit was visualized directly on the membrane after staining 40 sec in 0.03% methylene blue in 3M NaOAc at pH 5.2 with subsequent destaining in water.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants GM 59803 and AI 50237. M.E.V.E. and M.P.B. were supported by a NIAID training grant (T32 AI07471) in molecular virology. We thank P. Younan for his technical assistance.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

IAP, inhibitor of apoptosis protein

eGFP, enhanced green fluorescence protein

β-Gal, beta-Galactosidase

ORF, open reading frame

UTR, untranslated region

uAUG, upstream AUG codon

iAUG, initiator AUG codon

RNP, ribonucleoprotein

SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5156804.

REFERENCES

- Ali, N. and Siddiqui, A. 1995. Interaction of polypyrimidine tract-binding protein with the 5′ noncoding region of the hepatitis C virus RNA genome and its functional requirement in internal initiation of translation. J. Virol. 69: 6367–6375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyn, L.B., Towner, J.S., Semler, B.L., and Ehrenfeld, E. 1997. Requirement of poly(rC) binding protein 2 for translation of poliovirus RNA. J. Virol. 71: 6243–6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovee, M.L., Lamphear, B.J., Rhoads, R.E., and Lloyd, R.E. 1998. Direct cleavage of eIF4G by poliovirus 2A protease is inefficient in vitro. Virology 245: 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, M.P., Zamora, M., and Lloyd, R.E. 2002. Generation of multiple isoforms of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI by use of alternate translation initiation codons. Mol. Cell Biol. 22: 4499–4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.A., Xu, N., and Shyu, A.B. 1995. MRNA decay mediated by two distinct AU-rich elements from c-fos and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating transcripts: Different deadenylation kinetics and uncoupling from translation. Mol. Cell Biol. 15: 5777–5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux, Q.L. and Reed, J.C. 1999. IAP family proteins—Suppressors of apoptosis. Genes & Dev. 13: 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux, Q.L., Takahashi, R., Salvesen, G.S., and Reed, J.C. 1997. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature 388: 300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekedahl, J., Joseph, B., Grigoriev, M.Y., Muller, M., Magnusson, C., Lewensohn, R., and Zhivotovsky, B. 2002. Expression of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in small- and non-small-cell lung carcinoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 279: 277–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekert, P.G., Silke, J., and Vaux, D.L. 1999. Caspase inhibitors. Cell Death Differ. 6: 1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale, M., Tan, S., and Katze, M.G. 2000. Translational control of viral gene expression in eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64: 239–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambidge, S.J. and Sarnow, P. 1992. Translational enhancement of the poliovirus 5′ noncoding region mediated by virus-encoded polypeptide 2A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89: 10272–10276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellen, C.U. and Sarnow, P. 2001. Internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNA molecules. Genes & Dev. 15: 1593–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellen, C.U., Witherell, G.W., Schmid, M., Shin, S.H., Pestova, T.V., Gil, A., and Wimmer, E. 1993. A cytoplasmic 57-kDa protein that is required for translation of picornavirus RNA by internal ribosomal entry is identical to the nuclear pyrimidine tract-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90: 7642–7646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner, M.O. 2000. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 407: 770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henis-Korenblit, S., Shani, G., Sines, T., Marash, L., Shohat, G., and Kimchi, A. 2002. The caspases-cleaved DAP5 protein supports internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation of death proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 5400–5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, M.G., Norton, R.S., Vaux, D.L., and Day, C.L. 1999. Solution structure of a baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) repeat. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6: 648–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik, M. and Korneluk, R.G. 2000. Functional characterization of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) internal ribosome entry site element: Role of La autoantigen in XIAP translation. Mol. Cell Biol. 20: 4648–4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik, M., Lefebvre, C., Yeh, C., Chow, T., and Korneluk, R.G. 1999. A new internal-ribosome-entry-site motif potentiates XIAP-mediated cytoprotection. Nat. Cell. Biol. 1: 190–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik, M., Sonenberg, N., and Korneluk, R.G. 2000a. Internal ribosome initiation of translation and the control of cell death. Trends Genet. 16: 469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik, M., Yeh, C., Korneluk, R.G., and Chow, T. 2000b. Translational upregulation of apoptosis (XIAP) increases resistance to radiation induced cell death. Oncogene 19: 4174–4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik, M., Gordon, B.W., and Korneluk, R.G. 2003. The internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation of antiapoptotic protein XIAP is modulated by the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins C1 and C2. Mol. Cell Biol. 23: 280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda, S., Kaneko, S., Matsushita, E., Kobayashi, K., Abell, G.A., and Lemon, S.M. 2000. Cell cycle regulation of Hepatitis C Virus internal ribosomal entry site-directed translation. Gastroenterology 118: 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S. and Yang, X. 2003. Cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 1 and 2 are ubiquitin ligases for the apoptosis inducer Smac/DIABLO. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 10055–10060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes, G., Carter, M.S., Eisen, M.B., Brown, P.O., and Sarnow, P. 1999. Identification of eukaryotic mRNAs that are translated at reduced cap binding complex eIF4F concentrations using a cDNA microarray. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 13118–13123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. 1991. An analysis of vertebrate mRNA sequences: Intimations of translational control. J. Cell Biol. 115: 887–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1999. Initiation of translation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Gene 234: 187–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2001. New ways of initiating translation in eukaryotes? Mol. Cell Biol. 21: 1899–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002. Pushing the limits of the scanning mechanism for initiation of translation. Gene 299: 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyumcu-Martinez, N.M., Joachims, M., and Lloyd, R.E. 2002. Efficient cleavage of ribosome-associated poly(A)-binding protein by enterovirus 3C protease. J. Virol. 76: 2062–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCasse, E.C., Baird, S., Korneluk, R.G., and MacKenzie, A.E. 1998. The inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) and their emerging role in cancer. Oncogene 17: 3247–3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le, S.Y. and Maizel, J.V. 1997. A common RNA structural motif involved in the internal initiation of translation of cellular mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Yang, Y., and Ashwell, J.D. 2002. TNF-RII and c-IAP1 mediate ubiquitination and degradation of TRAF2. Nature 416: 345–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marissen, W.E. and Lloyd, R.E. 1998. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G is targeted for proteolytic cleavage by caspase 3 during inhibition of translation in apoptotic cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 18: 7565–7574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marissen, W.E., Gradi, A., Sonenberg, N., and Lloyd, R.E. 2000a. Cleavage of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GII correlates with translation inhibition during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 12: 1234–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marissen, W.E., Guo, Y., Thomas, A.A., Matts, R.L., and Lloyd, R.E. 2000b. Identification of caspases 3-mediated cleavage and functional alteration of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α in apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 9314–9323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerovitch, K., Svitkin, Y.V., Lee, H.S., Lejbkowicz, F., Kenan, D.J., Chan, E.K., Agol, V.I., Keene, J.D., and Sonenberg, N. 1993. La autoantigen enhances and corrects aberrant translation of poliovirus RNA in reticulocyte lysate. J. Virol. 67: 3798–3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrish, B.C. and Rumsby, M.G. 2002. The 5′ untranslated region of protein kinase Cδ directs translation by an internal ribosome entry segment that is most active in densly growing cells and during apoptosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 22: 6089–6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, D.W. 1999. Caspase structure, proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 6: 1028–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs, K., Saleh, L., Bassili, G., Sonntag, V.H., Zeller, A., and Niepmann, M. 2002. Interaction of translation initiation factor eIF4B with the poliovirus internal ribosome entry site. J. Virol. 76: 2113–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova, T.V., Kolupaeva, V.G., Lomakin, I.B., Pilipenko, E.V., Shatsky, I.N., Agol, V.I., and Hellen, C.U.T. 2001. Molecular mechanisms of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 7029–7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudi, R., Abhiman, S., Srinivasan, N., and Das, S. 2003. Hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation is stimulated by specific interaction of independent regions of human La autoantigen. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 12231–12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyronnet, S., Pradayrol, L., and Sonenberg, N. 2000. A cell cycle-dependent internal ribosome entry site. Mol. Cell 5: 607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajcan-Separovic, E., Liston, P., Lefebvre, C., and Korneluk, R.G. 1996. Assignment of human inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) genes xiap, hiap-1, and hiap-2 to chromosomes Xq25 and 11q22–23 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genomics 37: 404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, J.C. 2000. Mechanisms of apoptosis. Am. J. Pathol. 157: 1415–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe, M., Pan, M.G., Henzel, W.J., Ayres, T.M., and Goeddel, D.V. 1995. The TNFR2-TRAF signaling complex contains two novel proteins related to baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Cell 83: 1243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, N., Deveraux, Q.L., Takahashi, R., Salvesen, G.S., and Reed, J.C. 1997. The c-IAP-1 and c-IAP-2 proteins are direct inhibitors of specific caspases. EMBO J. 16: 6914–6925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabova, L.A. and Hohn, T. 2000. Ribosome shunting in the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S RNA leader is a special case of reinitiation of translation functioning in plant and animal systems. Genes & Dev. 14: 817–829. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvesen, G.S. and Duckett, C.S. 2002. IAP proteins: Blocking the road to death’s door. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3: 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnow, P. 2003. Viral internal ribosome entry site elements: Novel ribosome-RNA complexes and roles in viral pathogenesis. J. Virol. 77: 2801–2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, M. and Wimmer, E. 1994. IRES-controlled protein synthesis and genome replication of poliovirus. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 9: 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, I., Itin, A., Einat, P., Skaliter, R., Grossman, Z., and Keshet, E. 1998. Translation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by internal ribosome entry: Implications for translation under hypoxia. Mol. Cell Biol. 18: 3112–3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taba, Y., Miyagi, M., Miwa, Y., Inoue, H., Takahashi-Yanaga, F., Morimoto, S., and Sasaguri, T. 2003. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 and laminar fluid shear stress stabilize c-IAP1 in vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol Heart Circ. Physiol. 285: H38–H46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm, I., Kornblau, S.M., Segall, H., Krajewski, S., Welsh, K., Kitada, S., Scudiero, D.A., Tudor, G., Qui, Y.H., Monks, A., et al. 2000. Expression and prognostic significance of IAP-family genes in human cancers and myeloid leukemias. Clin. Cancer Res. 6: 1796–1803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eden, M.E., Byrd, M.P., Sherrill, K.W., and Lloyd, R.E. 2004. Demonstrating internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNAs using stringent RNA test procedures. RNA (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z. and Kiledjian, M. 2001. Functional link between the mammalian exosome and mRNA decapping. Cell 107: 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., Mayo, M.W., Korneluk, R.G., Goeddel, D.V., and Baldwin, A.S. 1998. NF-κB antiapoptosis: Induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science 281: 1680–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Fang, S., Jensen, J.P., Weissman, A.M., and Ashwell, J.D. 2000. Ubiquitin protein ligase activity of IAPs and their degradation in proteosomes in response to apoptotic stimuli. Science 288: 874–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.S., Liston, P., Xuan, J., McRoberts, C., Lefebvre, C.A., and Korneluk, R.G. 1999. Genomic organization and physical map of the human inhibitors of apoptosis: HIAP1 and HIAP2. Mamm. Genome 10: 44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora, M., Marissen, W.E., and Lloyd, R.E. 2002. Multiple eIF4GI-specific activities present in uninfected and poliovirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 76: 165–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]