Abstract

A specific and efficient method is presented for the conversion of 2′-deoxyuridine to thymidine via formation and reduction of the intermediate 5-hydroxymethyl derivative. The method has been used to generate both thymidine and 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine containing the stable isotopes 2H, 13C and 15N. Oligodeoxyribonucleotides have been constructed with these mass-tagged bases to investigate sequence-selectivity in hydroxyl radical reactions of pyrimidine methyl groups monitored by mass spectrometry. Studying the reactivity of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) is difficult as the reaction products can deaminate to the corresponding thymine derivatives, making the origin of the reaction products ambiguous. The method reported here can distinguish products derived from 5mC and thymine as well as investigate differences in reactivity for either base in different sequence contexts. The efficiency of formation of 5-hydroxymethyluracil from thymine is observed to be similar in magnitude in two different sequence contexts and when present in a mispair with guanine. The oxidation of 5mC proceeds slightly more efficiently than that of thymine and generates both 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and 5-formylcytosine but not the deaminated products. Thymine glycol is generated by both thymine and 5mC, although with reduced efficiency for 5mC. The method presented here should be widely applicable, enabling the examination of the reactivity of selected bases in DNA.

INTRODUCTION

The DNA of higher eucaryotes contains two 5-methylpyrimidines: thymine and 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Thymine is normally incorporated into the DNA of most organisms by DNA polymerase, whereas 5mC is generated in DNA by cytosine methyltransferase following DNA replication (1–3). Mutations at 5mC residues in DNA and alterations of cytosine methylation patterns are frequently observed in human cancer (4–7). We are interested in understanding the mechanisms by which the chemical reactivity of 5mC may result in genetic mutations and epigenetic changes.

Sensitive and specific methods are available for measuring damaged DNA bases, most of which are based upon mass spectrometry methods (8–13). Despite the advantages of these methods, they generally cannot be used to examine the reactivity at selected DNA bases in specific sequences because the DNA must be hydrolyzed (either enzymatically or chemically) prior to analysis resulting in subsequent loss of sequence information. Recently, we reported a method, which we call ‘mass tagging’, that allows us to retain sequence specificity with mass spectral-based methods of analysis (14). Using this method, a target cytosine residue in an oligodeoxyribonucleotide (ODN) was isotopically enriched by incorporation of a stable-isotope tagged precursor. Selectivity for enzymatic methylation at the target site was examined by analysis of the mass spectrum of the mass-tagged 5mC generated in the enzymatic reaction.

We wished to extend this method to understand the reactivity of pyrimidine methyl groups in DNA, including that of 5mC. Among the reaction products of 5mC are those that have lost the NH2-group, generating the corresponding thymine derivatives (15–17). We propose that mass tagging also could serve in this setting to distinguish potentially identical products that could have arisen from either 5mC or thymine.

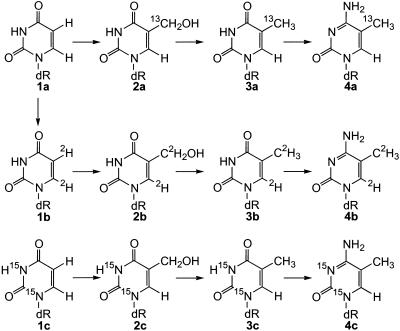

In order to utilize this mass tagging technique, a series of isotopically enriched 5-methyl pyrimidines must be synthesized. Previously, Ahmadian and Bergstrom (18) reported a method for the conversion of 2′-deoxyuridine (dU) to thymidine by direct methylation. In contrast to the experience of the Bergstrom group, we and others (19) find that both 5- and 6-methyl derivatives are generated in this reaction. Unfortunately, the 5- and 6-deoxynucleoside isomers are not easily separated on a preparative scale. As an alternative, we explored the conversion of 2′-dU to thymidine via the intermediate 5-hydroxymethyl derivative, which is converted to thymidine by catalytic hydrogenation, as shown previously for the free base (20). We find this latter pathway to be specific and efficient (Fig. 1). We have used this method to produce thymidine enriched with 2H, 13C and 15N. Additionally, all enriched thymidine derivatives have been converted to the corresponding 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine derivatives.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of 5-substituted pyrimidine derivatives labeled with 13C, 15N and 2H atoms.

ODNs containing the enriched pyrimidines have been prepared and used to explore the sequence specificity of the reaction with reactive oxygen species generated with Fenton chemistry (8–10,21). We find little difference in the formation of 5-hydroxymethyluracil (HmU) from thymine when in two different sequence contexts or when mispaired with guanine. The oxidation of 5mC generates 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (HmC) and 5-formylcytosine (FoC) with minimal deamination to the corresponding uracil derivatives. Both 5mC and thymine can form thymine-glycol (T-glycol). However, 5mC forms T-glycol to a lesser extent than does thymine. This method should generally be applicable to the study of sequence-specific reactivity of bases in ODNs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Stable-isotope precursors 13C formaldehyde (13C, 99%), 2H2 formaldehyde (2H2, 98%), deuterium gas and deuterium oxide (2H2, 99.9%) were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratory (Andover, MA). The 2′-dU was obtained from Chem-Impex International (Wood Dale, IL). DNA synthesis reagents were purchased from Glen Research. The 15N2-enriched 2′-dU was prepared as described previously (25). Phosphoramidites of normal DNA bases and solid supports were obtained from Glen Research. All other chemical reagents were obtained from Aldrich Chemical Co.

All silica gel flash chromatography was performed with Silica gel H (Fluka). The column dimensions for a 1 g scale purification were 3 cm height by 6 cm diameter. The column was eluted with methanol in dichloromethane from 0 to 20%. Column dimensions were increased or decreased based upon sample amount. Thin layer chromatography was performed with General Purpose Silica gel on glass plates (Aldrich). Plates were developed in a closed chamber with 5–20% methanol in dichloromethane.

Proton and carbon NMR spectra were obtained with a Varian Inova 600 MHz instrument (Caltech). Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS) was performed with a Hewlett Packard 5890 gas chromatograph interfaced with a 5970 mass selective detector. Samples containing 0.15 mg of ODNs were placed in a 1 ml reactivial (Pierce) and solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure. The dry samples were hydrolyzed in 88% formic acid (100 µl) at 140°C for 30 min. The solvents were evaporated and dry samples were reconstituted in 100 µl of acetonitrile and 100 µl of bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide which were sealed and heated at 140°C for 30 min. Each silylated sample (10 µl) was injected onto the gas chromatograph equipped with a Hewlett Packard silica capillary column (12 m × 0.20 mm) coated with cross-linked 5% phenylsilicone (film thickness, 0.33 µm). The following temperatures were used: 250°C for the injector, and 280°C for the detector interface. The oven temperature began at 100°C for 2 min and was then ramped to 260°C over 16 min. The final temperature was maintained for 2 min (12). Exact mass measurements were performed by the mass spectrometry facility at the University of California, Riverside.

Synthesis

Direct methylation of dU with methyl iodide. The method of Ahmadian and Bergstrom (18) was used for direct methylation of 2′-dU. Briefly, commercially available 2′-dU was converted to 3′,5′-bis-O-(t-butyldimethylsilyl)-2′-dU with t-butyldimethylsilyl chloride in N,N-dimethylformamide containing imidazole. The lithiation of the silyl intermediate was conducted in dry THF at –78°C with sec-butyl lithium and N,N,N′,N′,tetramethylethylenediamine under dry argon. The lithiated intermediate was methylated with methyl iodide at –78°C. Products were deprotected with t-butyldimethylaminofluoride, and separated by silica gel column chromatography. Samples were analyzed by GC/MS (Fig. 2).

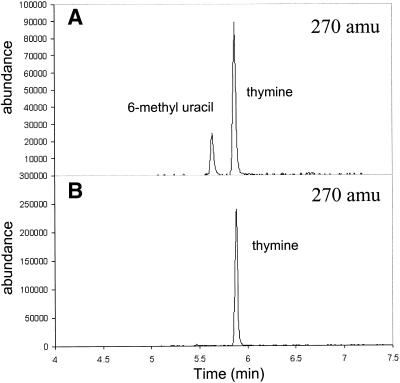

Figure 2.

Methyl pyrimidine reaction products obtained from direct methylation of 2′-dU and via formation and reduction of 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-dU. Products were hydrolyzed in formic acid, converted to the TMS derivative and analyzed by GC/MS. The selective ion profile (270 amu) for products of the Bergstrom method (A) and for our products (B) are shown.

Deuteration of 2′-dU. Unlabeled 2′-dU (0.5 g) was dissolved in 2H2O (10 ml), evaporated three times and then dissolved in 100 ml 2H2O. Platinum (IV) oxide catalyst was added (0.8 g) and the reaction mixture was stirred under a deuterium gas atmosphere for 1.5 h (22). The solvent was evaporated and the deuterated dU was isolated by silica gel column chromatography in 73% yield. Analysis by GC/MS and NMR indicated complete exchange of H5 and H6 protons.

Conversion of 2′-dU to 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-dU. dU (0.5 g) was dissolved in 20% aqueous formaldehyde solution (23–25). The deuterated derivative required deuterated formaldehyde in 2H2O (3 ml). The 13C-labeled derivative required 13C-formaldehyde (1.5 ml), and the 15N2-labeled derivative required unenriched aqueous formaldehyde (3 ml). Triethyl amine (4 ml) was added and the vials were sealed, vortexed and incubated at 60°C for 6 days. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the products were isolated by silica gel column chromatography in 40, 70 and 60% yields, respectively.

Conversion of 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-dU to thymidine. The intermediate 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2′-dU (2a, 2c, see Fig. 1) was reduced to thymidine by catalytic hydrogenation (26–28). The hydroxymethyl nucleoside (1 g, 3.8 mmol) was dissolved in acetic acid (50% solution, 100 ml) and platinum (IV) oxide was added (1.5 g). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1.5 h under hydrogen gas atmosphere and was bubbled every 15 min with fresh hydrogen gas. The catalyst was removed by filtration and solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure. The product was isolated by silica gel column chromatography in 54% (3a) and 69% (3c) yield.

(3a) 1H NMR (600 MHz, 2H6-DMSO) δ, 11.27 (s, NH), 7.70 (s, H6), 6.17 (t, H1′, J = 6.6 Hz), 5.22 (d, 3′OH), 5.01 (t, 5′OH), 4.23 (q, H3′), 3.76 (m, H4′), 3.57 (m, H5′, 5′′), 2.07 (m, H2′, 2′′), 1.77 (d, -CH3, J = 127 Hz).

13C NMR (2H6-DMSO) δ, 12.25 (q, -CH3).

(3c) 1H NMR (600 MHz, 2H6-DMSO) δ, 11.27 (d of d, NH, J = 91.2 Hz), 7.70 (s, H6), 6.17 (t, H1′, J = 6.6 Hz), 5.22 (d, 3′OH), 5.02 (t, 5′OH), 4.24 (q, H3′), 3.76 (m, H4′), 3.57 (m, H5′, 5′′), 2.07 (m, H2′, 2′′), 1.78 (s, -CH3).

2H4-Thymidine (3b). 2H3-5-(Hydroxymethyl)-2′-dU (2b) (1 g, 3.8 mmol) was co-evaporated with deuterium oxide (3 × 25 ml) and then dissolved in deuterium oxide (100 ml). The platinum (II) oxide was added (1.5 g) and the reaction was kept under deuterium gas atmosphere as described above. The catalyst was removed by filtration and solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The product was isolated by silica gel column chromatography in 60% yield.

(3b) 1H NMR (600 MHz, 2H6-DMSO) δ, 11.27 (s, NH), 6.17 (t, H1′, J = 6.6 Hz), 5.22 (d, 3′OH), 5.02 (t, 5′OH), 4.23 (q, H3′), 3.76 (m, H4′), 3.57 (m, H5′, 5′′), 2.07 (m, H2′, 2′′).

Conversion of thymidine to 5-methyl-2′-dC. Labeled thymidine was converted to 5-methyl-2′-dC by the method of Divakar and Reese (29,30). Labeled thymidine (3a–3c) (1g, 4 mmol) was dried by co-evaporation with dry pyridine (3 × 25 ml). The residue was dissolved in pyridine (20 ml) and then acetic anhydride was added (3 ml). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The solvents were removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried by co-evaporation with toluene.

Triethylamine (5.3 ml) was added drop-wise into a stirred, cooled solution of 1,2,4-triazole (2.76 mg) and POCl3 (0.8 ml) in acetonitrile (25 ml). The labeled thymidine was suspended in acetonitrile and then added to the resulting mixture and the reaction mixture was stirred for 45 min at room temperature. Triethylamine (1 ml) and water (0.2 ml) were then added, and after 10 min the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in dichloromethane and washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate. The organic layer was dried over sodium sulfate and filtered; then the solvent was evaporated.

The residue was dissolved in either methanolic ammonia (3a, 3c) or 2H5-ammonium deuteroxide (26% solution in 2H2O) (3b). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. Solvent was evaporated and product was isolated by silica gel column chromatography in 62% (4a), 66% (4b) and 58% (4c) yields.

(4a) 1H NMR (600 MHz, 2H6-DMSO) δ, 7.64 (s, H6), 7.32 (s, NH), 6.84 (s, NH), 6.17 (t, H1′, J = 6–7 Hz), 5.21 (d, 3′OH), 5.03 (t, 5′OH), 4.21 (m, H3′), 3.74 (m, H4′), 3.55 (m, H5′, H5′′), 2.06 (m, H2′, H2′′), 1.834 (d, -CH3, J = 127 Hz).

(4b) 1H NMR (600 MHz, 2H6-DMSO) δ, 7.32 (s, NH), 6.86 (s, NH), 6.16 (t, H1′, J = 6–7 Hz), 5.20 (d, 3′OH), 5.03 (t, 5′OH), 4.20 (m, H3′), 3.74 (m, H4′), 3.55 (m, H5′, H5′′), 2.01 (m, H2′, H2′′).

(4c) 1H NMR (600 MHz, 2H6-DMSO) δ, 7.66 (s, H6), 7.38 (s, NH), 6.93 (s, NH), 6.16 (t, H1′, J = 6–7 Hz), 5.22 (d, 3′OH), 5.04 (t, 5′OH), 4.18 (m, H3′), 3.75 (m, H4′), 3.56 (m, H5′, H5′′), 2.01 (m, H2′, H2′′), 1.84 (s, -CH3).

Preparation of mass-tagged ODNs. Deoxynucleosides were converted to the phosphoramidite derivatives for solid phase synthesis by standard procedures (14,31,32). ODNs were synthesized on an automated DNA synthesizer using standard phosphoramidites and coupling conditions. ODNs were liberated from the solid support and deprotected in aqueous ammonia at 60°C overnight. Purification utilized sep-pak cartridges. The composition of the ODNs was verified by GC/MS analysis.

Reaction of ODNs with reactive oxygen species

Double-stranded DNA fragments (40 µM) were treated with Fe (III)-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)/H2O2/ascorbic acid (5 mM H2O2, 0.1 mM FeCl3, 0.5 mM NTA and 0.5 M ascorbic acid) in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 25°C overnight (8–10,21). The ferric-ion solution was prepared immediately before addition to the other components. The following self-complementary ODNs were used for oxidation: d(CGTGAATTCACG), d(CGTGAATTCGCG), d(CGMGAATTCGCG) (M represents 5mC and T 1,3-15N2-thymine) (see Fig. 3). After oxidation the resulting ODNs were isolated by HPLC. Then 2.5 nmol of 6-azathymine (internal standard) was added. The oxidized samples, in addition to untreated control ODNs, were hydrolyzed (88% formic acid, 140°C, 30 min), evaporated and incubated in water at 60°C for 30 min. Upon drying, the samples were silylated and analyzed by GC/MS. The untreated control samples showed no measurable oxidative alteration of the DNA bases. Trace amounts of cytosine are known to be hydrolyzed to uracil under these conditions. Potential artifacts in the measurement of HmU in DNA following formic acid hydrolysis have been addressed previously (12).

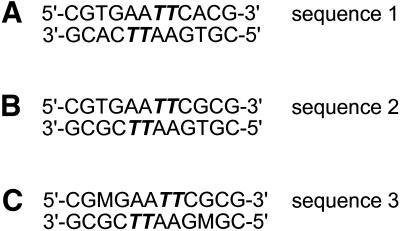

Figure 3.

Sequences of self-complementary ODNs used for oxidation by Fenton-type reagent, where M = 5mC and T = 15N2-thymine (enriched). (A) Sequence 1: ODN containing enriched thymine at the inner positions (T:A base pair) and unenriched thymine (in a T:A base pair) at the outer position. (B) Sequence 2: ODN containing enriched thymine (inner positions, T:A base pair) and unenriched thymine at the outer position (T:G mispair). (C) Sequence 3: ODN containing enriched thymine (inner positions, T:A base pair) and unenriched 5mC (outer position, 5mC:G base pair).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis

Thymidine has been generated previously by direct methylation of dU (18). While the Bergstrom group succeeded in generating thymidine as the exclusive product, we and others (19) observe formation of both the 5-methyl (thymidine) and 6-methyl products as shown in Figure 2. We were unable to separate the 5-methyl and 6-methyl-2′-dU derivatives on a preparative scale. As an alternative, we investigated the formation of thymidine via reduction of the intermediate 5-hydroxymethyl derivative, which is formed easily from 2′-dU in aqueous alkaline formaldehyde (25). Enriched formaldehyde containing both deuterium and 13C is readily available (33). Reduction proceeds in high yield with few side products. This alternative method therefore provides thymidine without the complication of the unwanted 6-methyl derivative.

We first attempted to prepare thymidine with one deuterium atom on the methyl group by reduction of unenriched HmdU under deuterium gas. However, the mass spectrum of the product revealed that an additional exchange had occurred during reduction. Previously, it had been noted that the methyl protons of thymidine are exchanged under the conditions used here for the reduction of HmdU (26–28). Heterogeneous mixtures of enriched analogs are of limited use in mass spectral studies, and so we attempted to generate thymidine with three protons on the methyl group starting with unenriched HmdU. Although substantial exchange was noted upon reduction of HmdU in 2H2O under 2H2 gas, we obtained a distribution of isotopomers. Surprisingly, the mass spectrum revealed the presence of molecules containing three as well as four deuterium atoms. The NMR spectrum indicated that the methyl protons underwent complete exchange, and that the H6 position underwent partial exchange. We therefore prepared dU deuterated in both the 5- and 6-positions as a starting material (22) as shown in Figure 1 (1b). Using deuterated formaldehyde followed by reduction in 2H2O under 2H2 gas, we succeeded in preparing fully deuterated thymidine. Previously, fully deuterated thymidine has been prepared from deuterated thymine (33).

The formation of thymidine containing both 13C and 15N proceeded without complication and with an acceptable yield. All thymidine derivatives were also converted to the corresponding 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine derivatives. The identity of each derivative was confirmed by NMR and high-resolution mass spectrometry (Table 1). The pathway indicated in Figure 1 therefore provides a complete set of 5-methylpyrimidine deoxynucleosides suitable for use as isotope standards for mass spectrometry (34–36), as isotope-labeled derivatives for NMR studies (37–41) and as mass-tagged analogs for the examination of base reactivity in DNA (14). The isotope enriched pyrimidine analogs were protected and incorporated into synthetic ODNs using standard procedures. A series of ODNs was constructed based upon the Dickerson dodecamer (42) as shown in Figure 3.

Table 1. High-resolution mass determinations obtained in the positive ion mode for stable-isotope enriched pyrimidine deoxynucleosides.

| Compound | Mass (H+) calculated | Mass (H+) experimental |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-dT 3a | 244.1014 | 244.1013 |

| 13C-mdC 4a | 243.1174 | 243.1180 |

| 2H4-dT 3b | 247.1227 | 247.1240 |

| 2H4-mdC 4b | 246.1387 | 246.1395 |

| 15N2-dT 3c | 245.0921 | 245.0918 |

| 15N2-mdC 4c | 244.1081 | 244.1084 |

Reactivity towards hydroxyl radicals

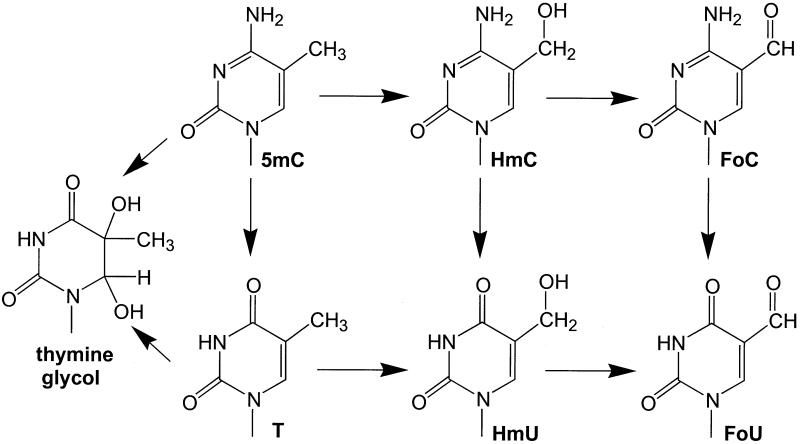

The thymine methyl group in DNA is a frequent site of oxidative modification (Fig. 4). Oxidation products include 5-HmU and 5-formyluracil (FoU) (43–46). Recently, it has been demonstrated that the substitution of thymine with 5-HmU can inhibit the binding of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins including transcription factors (47). Although HmU does not miscode during DNA replication (48), FoU does miscode and its formation in DNA can result in base substitution mutations (49–51). The methyl group in 5mC can be similarly oxidized to 5-HmC and 5-FoC (52,53). The chemical reactivity of 5mC may play a role in the observed biological properties of this base, specifically the observed frequency of transition mutations at 5mC found in many human tumors and the involvement of 5mC in directing chromatin condensation (54,55).

Figure 4.

Reaction pathways for thymine and 5mC.

Other biological processes may involve oxidized derivatives of 5mC as well. Recently, we identified a repair activity in human cell extracts that had unexpectedly high activity against HmU mispaired with guanine in DNA (16). The HmU:G mispair in DNA could be derived from a 5mC:G base pair by oxidation and deamination. As shown in Figure 4, this transformation could occur by two different pathways: either oxidation followed by deamination or deamination followed by oxidation. The expected rate of formation of the HmU:G lesion is estimated to be one per cell per 2000 years (16). However, the repair activity directed at this lesion exceeds, by several orders of magnitude, the repair activity of several other lesions thought to occur much more frequently, including the T:G mispair, which is believed to be the intermediate in the 5mC mutation pathway. The ability of the 5mC or T methyl group to be oxidized in DNA may play a role in the 5mC mutation pathway, as well as possibly explain the unusually high repair activity against HmU:G present in human cells. Prior to the method presented here it would have been difficult to determine whether HmU had been derived from 5mC or T.

In order to investigate further the pathways surrounding this unexpectedly high repair activity against HmU:G, we sought to determine (i) if the methyl group of 5mC in DNA is substantially more reactive than that of thymine and (ii) if the methyl group of thymine in a T:G mispair is more accessible and therefore more susceptible to radical attack. There have been several difficulties involved in addressing these questions previously. The difficulty in addressing the first question is that the potential oxidation and deamination product of 5mC, HmU, cannot be distinguished from thymine-derived HmU when the latter is in substantial excess (Fig. 4). The problem in addressing the second question is that the sequence information is lost once the DNA is hydrolyzed for analysis, greatly complicating the study of a particular mispair within an ODN.

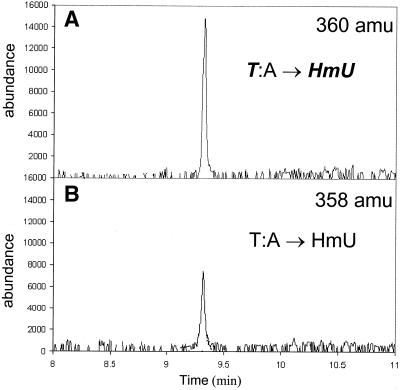

The mass-tagging approach described here, which overcomes both these difficulties, seemed ideal to answer both questions regarding the reactivities of the methyl groups on 5mC and thymine. We conducted several experiments using this technique. In the first experiment, a self-complementary ODN was prepared in which the two inner thymine residues were mass-tagged with 15N, and the outer thymine of a T:A base pair was unenriched (Fig. 3A, sequence 1). The ODN was subject to oxidation with commonly used Fenton chemistry. Following oxidation, the ODN was hydrolyzed and the base products analyzed by GC/MS. As shown in Figure 5, HmU was detected. The HmU monitored at 360 amu is derived from the two inner mass-tagged thymine residues whereas the HmU at 358 amu is derived from the unenriched outer thymine. The heavy to light ratio of the HmU derivatives is the same as that of the heavy to light ratio of thymine residues in the ODN, indicating that the thymine at the outer position has similar reactivity as that of the inner thymine residues. Surprisingly, in contrast to our control studies with monomers, we did not observe the formation of FoU. However, we did see trace amounts of 5-carboxyuracil. As was discussed in another study (21), we suspect that FoU undergoes further oxidation to the 5-carboxy derivative. Thus, in this experiment we have shown that the reactivity of the methyl group of thymine is not affected by sequence position on this self-complementary ODN duplex.

Figure 5.

Formation of HmU in T:A base pairs. GC/MS trace at 360 amu (A) and 358 amu (B) of a silylated hydrolysate of duplex sequence 1 containing T:A base pair treated with Fe(III)NTA/H2O2/ascorbic acid.

We next constructed an ODN of similar sequence in which the outer thymine residue is mispaired with guanine (Fig. 3B, sequence 2). We observed similar reactivity for the correctly paired and the mispaired thymine residues (data not shown). This result indicates that mispaired thymine is not more susceptible to subsequent oxidation with Fenton chemistry as compared with correctly paired thymine. Thus, we may conclude that the geometry and thermal stability of a thymine residue in DNA do not substantially affect the ability of its methyl group to be oxidized.

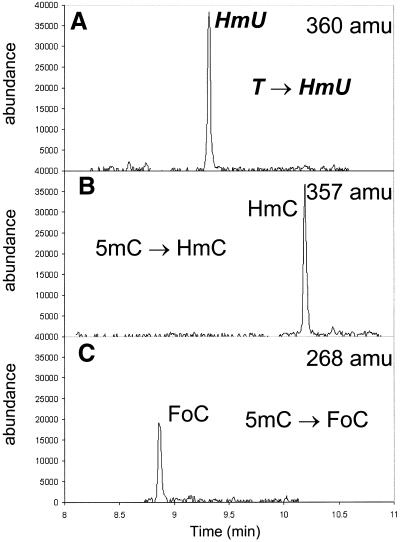

A third ODN was then constructed in which the outer thymine residue was replaced with 5mC (Fig. 3C, sequence 3). As shown in Figure 6, upon subjection of this ODN to the Fenton reaction, HmU was formed from the internal thymine residues as discussed above. The predominant products from 5mC were HmC and FoC. Based upon the integrated peak areas, the 5mC methyl group in the sequence studied is approximately twice as reactive toward Fenton oxidation as thymine in the same sequence. Both HmC and FoC are formed in roughly equal amounts. Traces of unenriched HmU were observed, although the levels did not exceed those resulting from deamination during standard acid hydrolysis of 5mC-, C- and HmC-containing ODNs (56).

Figure 6.

Formation of HmU from a T:A base pair and formation of HmC and FoC from a 5mC:G base pair. GC/MS trace at 360 amu (A), 357 amu (B) and 268 amu (C) of a silylated hydrolysate of duplex sequence 3 (containing a 5mC:G base pair) treated with Fe(III)NTA/H2O2/ascorbic acid.

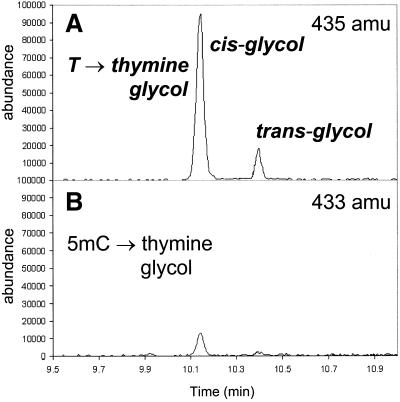

Hydroxyl radical oxidation of thymine can also generate thymine glycol. We observe both cis and trans isomers (Fig. 7). The extent of formation or distribution of isomers did not change for thymine in the outer position when paired with A or mispaired with G. The glycol formed from 5mC is known to undergo rapid deamination (17). Although we do observe thymine glycol derived from 5mC, the extent of formation is somewhat lower and the trans isomer is more dominant than it is for thymine. Thymine glycol is primarily disruptive because it blocks DNA replication. However, it can also be mutagenic by coding as thymine, which would give rise to 5mC→T transition mutations (57–59). Our observation that thymine glycol can be derived from 5mC illustrates that in DNA the chemical reactivity of 5mC may play a role in the high number of transition mutations observed at CpG dinucleotides.

Figure 7.

Formation of thymine glycol from T:A and 5mC:G base pairs. GC/MS trace at 435 amu (A) and 433 amu (B) of a silylated hydrolysate of duplex sequence 3 Fe(III)NTA/H2O2/ascorbic acid.

We present here a method for examining the reactivity of target bases in duplex DNA. With this method, we have determined that the reactivity of the thymine methyl group is similar in two different sequence contexts and base-pairing environments. The methyl group of 5mC is proportionally more reactive than that of thymine in forming both HmC and FoC derivatives. With Fenton chemistry, we do not see evidence of an enhanced oxidation and deamination process which might explain the previously reported high level of HmU:G repair activity in human cells (16). The method reported here, however, is amenable to the examination of a multitude of DNA damaging conditions, including peroxynitrite species with potential oxidizing and deaminating properties.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr Scott Ross of the NMR facility at the California Institute of Technology for his assistance. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health GM50351 and CA84487.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ehrlich M. and Wang,R.Y.-H. (1981) 5-Methylcytosine in eukaryotic DNA. Science, 212, 1350–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riggs A.D. and Jones,P.A. (1983) 5-Methylcytosine, gene regulation and cancer. Adv. Cancer Res., 40, 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doerfler W. (1983) DNA Methylation and gene activity. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 52, 93–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones P.A. and Buckley,J.D. (1990) The role of DNA methylation in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res., 54, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones P.A., Rideout,W.M.,III, Shen,J-C., Spruck,C.H. and Tsai,Y.C. (1992) Methylation, mutation and cancer. Bioessays, 14, 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmutte C. and Jones,P.A. (1998) Involvement of DNA methylation in human carcinogenesis. Biol. Chem., 379, 377–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santini V., Kantarjian,H.M. and Issa,J-P. (2001) Changes in DNA methylation in neoplasia: pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Ann. Intern. Med., 134, 573–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dizdaroglu M. (1985) Application of capillary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to chemical characterization of radiation-induced base damage of DNA: implications for assessing DNA repair processes. Anal. Biochem., 144, 593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aruoma O.I., Halliwell,B., Gajewski,E. and Dizdaroglu,M. (1989) Damage to the bases in DNA induced by hydrogen peroxide and ferric ion chelates. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 20509–20512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dizdaroglu M., Rao,G., Halliwell,B. and Gajewski,E. (1991) Damage to the DNA bases in mammalian chromatin by hydrogen peroxide in the presence of ferric and cupric ions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 285, 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aruoma O.I., Halliwell,B. and Dizdaroglu,M. (1989) Iron ion-dependent modification of bases in DNA by the superoxide radical-generating system hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 13024–13028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaFrancois C.J., Yu,K. and Sowers,L.C. (1998) Quantification of 5-(hydroxymethyl)uracil in DNA by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry: problems and solutions. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 11, 786–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dizdaroglu M. (1993) Quantitative determination of oxidative base damage in DNA by stable isotope-dilution mass spectrometry. FEBS lett., 315, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rusmintratip V., Riggs,A.D. and Sowers,L.C. (2000) Examination of the DNA substrate selectivity of DNA cytosine methyltransferases using mass tagging. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3594–3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Privat E. and Sowers,L.C. (1996) Photochemical deamination and demethylation of 5-methylcytosine. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 9, 745–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rusmintratip V. and Sowers,L.C. (2000) An unexpectedly high excision capacity for mispaired 5-hydroxymethyluracil in human cell extracts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 14183–14187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuo S., Boorstein,R.J. and Teebor,G.W. (1995) Oxidative damage to 5-methylcytosine in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 3239–3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadian M. and Bergstrom,D.E. (1998) Simple and regioselective synthesis of 13C-methyl-labeled thymidine. Nucl. Nucl., 17, 1183–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong R.W., Gupta,S. and Whelihan,F. (1989) Synthesis of 5-substituted nucleosides via the regioselective lithation of 2′-deoxyuridine. Tetra. Lett., 30, 2057–2060. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cline R.E., Fink,R.M. and Fink,K. (1959) Synthesis of 5-substituted pyrimidines via formaldehyde addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 81, 2521–2527. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murata-Kamiya N., Kamiya,H., Karino,N., Ueno,Y., Kaji,H., Matsuda,A. and Kasai,H. (1999) Formation of 5-formyl-2′-deoxycytidine from 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine in duplex DNA by Fenton-type reactions and γ-irradiation. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 4385–4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeda M. and Kawazoe,Y. (1975) Chemical alteration of nucleic acids and their components. Tetra. Lett., 19, 1643–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiau G.T., Schinazi,R.F. Chen,M.S. and Prusoff,W.H. (1980) Synthesis and biological activities of 5-(hydroxymethyl, azidomethyl, or aminomethyl)-2′-deoxyuridine and related 5′-substituted analogues. J. Med. Chem., 23, 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaFrancois C.J., Fujimoto,J. and Sowers,L.C. (1998) Synthesis and characterization of isotopically enriched pyrimidine deoxynucleoside oxidation damage products. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 11, 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda K., Tanaka,S. and Mizuno,Y. (1975) Synthesis of potential antimetabolites. XX. Synthesis of 5-carbomethoxymethyl- and 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine (the ‘first letters’ of some anticodons) and closely related nucleosides from uridine. Chem. Pharm. Bull., 23, 2958–2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brush C.K., Stone,M.P. and Harris,T.M. (1988) Selective deuteriation as an aid in the assignment of 1H NMR spectra of single-stranded oligonucleotides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 110, 4405–4408. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kintanar A., Alam,T.M., Huang,W.C., Schindele,D.C., Wemmer,D.E. and Drobny,G. (1988) Solid-state 2H NMR investigation of internal motion in 2′-deoxythymidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 11, 6367–6372. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffey R.H. and Poulter,C.D. (1983) Efficient synthesis of [3-15N]uracil and [3-15N]thymine. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 6497–6504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Divakar K.J. and Reese,C.B. (1982) 4-(1,2,4-Triazol-1-yl)- and 4-(3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)-1-(β-d-2,3,5-tri-O-acetylarabinofuranosyl)pyrimidin-2(1H)-ones. Valuable intermediates in the synthesis of derivatives of 1-(β-d-arabinofuranosyl) cytosine (Ara-C). J. Chem. Soc. [Perkin], 1171–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox J.J., Van Praag,D., Wempen,I., Doerr,I.L., Cheong,L., Knoll,J.E., Eidinoff,M.L., Bendich,A. and Brown,G.B. (1959) Thiation of nucleosides. II. Synthesis of 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine and related pyrimidine nucleosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 81, 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gait M.J. (1984) Oligonucleotide Synthesis, A Practical Approach. IRL Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 31–81.

- 32.Nielsen J., Taagaard,M., Marugg,J.E., van Boom,J.H. and Dahl,O. (1986) Application of 2-cyanoethyl-N,N,N′,N′-tetraisopropylphosphoramidite for in situ preparation of 2′-deoxyribonucleoside phosphoramidites and their use in polymer supported synthesis of oligodeoxyribonucleosides. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 7391–7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawson J.A. and DeGraw,J.I. (1968) Labeling of atoms in pyrimidine residues of pyrimidine nucleosides. In Zorbach,W.W. and Tipson,R.S. (eds), Synthetic Procedures in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. Interscience Publishers, New York, pp. 921–925.

- 34.Djuric Z., Luongo,D.A. and Harper,D.A. (1991) Quantitation of 5-(hydroxymethyl)uracil in DNA by gas chromatography with mass spectral detection. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 4, 687–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamberg M. and Zhang,L-Y. (1995) Quantitative determination of 8-hydroxyguanine and guanine by isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem., 229, 336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kline P.C., Razaee,M. and Lee,T.A. (1999) Determination of kinetic isotope effects for nucleoside hydrolases using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem., 275, 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sowers L.C., Eritja,R., Chen,F.M., Khwaja,T., Kaplan,B., Goodman,M.F. and Fazakerley,G.V. (1989) Characterization of the pH wobble structure of the 2-aminopurine-cytosine mismatch by N-15 NMR spectroscopy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 165, 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LaFrancois C.J., Fujimoto,J. and Sowers,L.C. (1999) Synthesis and utilization of 13C(8)-enriched purines. Nucl. Nucl., 18, 23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sowers L.C., Boulard,Y. and Fazakerley,G.V. (2000) Multiple structures for the 2-aminopurine-cytosine mispair. Biochemistry, 39, 7613–7620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sowers L.C. (2000) 15N-Enriched 5-fluorocytosine as a probe for examining unusual DNA structures. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 17, 713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.SantaLucia J., Shen,L.X., Cai,Z., Lewis,H. and Tinoco,I.,Jr (1995) Synthesis and NMR of RNA with selective isotopic enrichment in the bases. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 4913–4921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon C., Prive,G.G., Goodsell,D.S. and Dickerson,R.E. (1988) Structure of an alternating-B DNA helix and its relationship to A-tract DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 6332–6336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teebor G.W., Frenkel,K. and Goldstein,M.S. (1984) Ionizing radiation and tritium transmutation both cause formation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine in cellular DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 81, 318–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frenkel K., Cummings,A., Solomon,J., Cadet,J., Steinberg,J.J. and Teebor,G.W. (1985) Quantitative determination of the 5-(hydroxymethyl)uracil moiety in the DNA of gamma-irradiated cells. Biochemistry, 24, 4527–4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasai H., Iida,A., Yamaizumi,Z., Nishimura,S. and Tanooka,H. (1990) 5-Formyldeoxyuridine: a new type of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation and its mutagenicity to salmonella strain TA102. Mutat. Res., 243, 249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bjelland S., Eide,L., Time,R.W., Stote,R., Eftedal,I., Volden,G. and Seeberg,E. (1995) Oxidation of thymine to 5-formyluracil in DNA: Mechanisms of formation, structural implications and base excision by human cell free extracts. Biochemistry, 34, 14758–14764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rogstad D.K., Liu,P., Burdzy,A., Lin,S.S. and Sowers,L.C. (2002) Endogenous DNA lesions can inhibit the binding of the AP-1 (c-Jun) transcription factor. Biochemistry, 41, 8093–8102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy D.D. and Teebor,G.W. (1991) Site directed substitution of 5-hydroxymethyluracil for thymine in replicating phi X-174am3 DNA via synthesis of 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 3337–3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Privat E.J. and Sowers,L.C. (1996) A proposed mechanism for the mutagenicity of 5-formyluracil. Mutat. Res., 354, 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masaoka A., Terato,H., Kobayashi,M., Ohyama,Y. and Ide,H. (2001) Oxidation of thymine to 5-formyluracil in DNA promotes misincorporation of dGMP and subsequent elongation of a mismatched primer terminus by DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 16501–16510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castro G.D., Diaz Gomez,M.I. and Castro,J.A. (1996) 5-Methylcytosine attack by hydroxyl free radicals and during carbon tetrachloride promoted liver microsomal lipid peroxidation: structure of reaction products. Chem. Biol. Interact., 99, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cier A., Lefier,A., Ravier,M. and Nofre,C. (1962) Action du radical libre hydroxyle sur les bases pyrimidiques (The action of free hydroxyl radicals on the pyrimidine bases). Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Seances de L’Academie des Sciences, 254, 504–506. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lion Y. and Van de Vorst,A. (1974) Radicaux libres radioinduits dans les solutions gelées de 5-méthylcytosine (Radiation-induced free radicals in frozen solutions of 5-methylcytosine). Int. J. Radiat. Biol., 25, 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nan X., Ng,H.H., Johnson,C.A., Laherty,C.D., Turner,B.M., Eisenman,R.N. and Bird,A. (1998) Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature, 393, 386–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones P.L., Veenstra,G.J., Wade,P.A., Vermaak,D., Kass,S.U., Landsberger,N., Strouboulis,J. and Wolffe,A.P. (1998) Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature Genet., 19, 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tardy-Planechaud S., Fujimoto,J., Lin,S.S. and Sowers,L.C. (1997) Solid phase synthesis and restriction endonuclease cleavage of oligodeoxyribonucleotides containing 5-(hydroxymethyl)-cytosine. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 553–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark J.M. and Beardsley,G.P. (1989) Template length, sequence context and 3′-5′ exonuclease activity modulate replicative bypass of thymine glycol lesions in vitro. Biochemistry, 28, 775–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McNulty J.M., Jerkovic,B., Bolton,P.H. and Basu,A.K. (1998) Replication inhibition and miscoding properties of DNA templates containing a site-specific cis-thymine glycol or urea residue. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 11, 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tornaletti S., Maeda,L.S., Lloyd,D.R., Reines,D. and Hanawalt,P.C. (2001) Effect of thymine glycol on transcription elongation by T7 RNA polymerase and mammalian RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 45367–45371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]