Abstract

mRNA turnover is a regulated process that contributes to the steady state level of cytoplasmic mRNA. The amount of each mRNA determines, to a large extent, the amount of protein produced by that particular transcript. In trypanosomes, there is little transcriptional regulation; therefore, differential mRNA stability significantly contributes to mRNA levels in each stage of the parasite life cycle. To investigate the enzymatic activities that contribute to mRNA turnover, we developed a cell-free system for mRNA turnover using the trypanosome Leptomonas seymouri. We identified a decapping activity that removed m7GDP from mRNAs that contain an m7GpppN cap at their 5′ end. In yeast, the release of m7GDP by the pyrophosphatase Dcp1p/Dcp2p is a rate-limiting step in mRNA turnover. A secondary enzymatic activity, similar to the human cap scavenger activity, was identified in the trypanosome extracts. Both the human and trypanosome scavenger activities generate m7GMP from short capped RNA and are inhibited by addition in trans of m7GpppG. A third enzymatic activity uncovered in the parasite extracts functioned as a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease. Importantly, this exonuclease activity was stimulated by an AU-rich element present in the RNA. In summary, the cell-free system has defined several RNA turnover steps that likely contribute to regulated mRNA decay in trypanosomes.

INTRODUCTION

mRNA levels in eukaryotic cells are regulated in part by differential mRNA stability (1,2). The half-life of each mRNA can be altered in response to various internal and external signals. These signals are capable of modifying gene expression through their regulation of RNA turnover pathways (3–5). The processes that regulate mRNA stability are mediated by a complex set of protein–protein and protein–RNA interactions. Central to these interactions are the 5′ m7GpppN cap and the 3′ poly(A) tail of the mRNA. Removal of these two structures leads to instability of an mRNA and the turnover of the body of the mRNA.

Advances in the past decade in yeast demonstrated that in this system the main RNA decay pathway consists of the removal of the protective 5′ cap and the 3′ poly(A) tail in an ordered process (1,6,7). This major pathway is initiated by deadenylation of the mRNA, followed by decapping and 5′ to 3′ exonucleolytic decay. Several exonucleases have been identified in yeast that exhibit deadenylation activity. These include Ccr4p, Pan2p and Pop2p (8–10). Deletion of any of the genes that encodes these three deadenylases is not lethal (11,12). Recently it was shown that Ccr4p and Pop2p are components of a complex that function as the cytoplasmic deadenylase in yeast (9,10). Decapping of the 5′ m7GpppN end of mRNA is catalyzed by the enzyme Dcp1p/Dcp2p (13). This enzyme recognizes a capped mRNA and releases m7GDP from the 5′ m7GpppN end of the transcript (14). After cap removal, the mRNA is sensitive to the 5′ to 3′ exonucleolytic activity of Xrn1p (15). By following an alternative pathway in yeast, some deadenylated mRNAs are degraded by the exosome complex, which contains multiple 3′ to 5′ exonucleolytic activities (1,16,17). A cap scavenger activity, attributed to DcpS1p, releases m7GMP from the 5′ end of short RNA fragments generated by the exosome activity (18). Recent work has shown that mRNAs that are completely free of any stop codon are rapidly degraded by an exosome-mediated pathway (19). A third characterized pathway in yeast functions to degrade mRNAs that contain premature stop codons. Cap removal in this pathway, called the nonsense medicated decay (NMD) pathway, is independent of a deadenylation step (20).

In vitro assay systems have identified key components of mRNA decay pathways in mammalian cells. A decapping activity that released m7GDP from capped mRNAs was discovered in S100 extracts from HeLa cells (21). This activity was functionally equivalent to yeast Dcp1p/Dcp2p because both activities release m7GDP from capped RNAs and are stimulated by addition of cap analog (m7GpppG) to the reaction (14,21). A deadenylating exonuclease (PARN) functions to remove poly(A) tails from capped mRNA in vitro (5,22). This enzyme has been purified from HeLa extracts, has a molecular mass of 74 kDa protein and functions in a distributive fashion to degrade poly(A) sequences (23–25). Finally, 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activities present in exosome complexes in HeLa cytoplasmic extracts play a role in mRNA turnover (18,26). The kinetics of exosome-mediated mRNA decay in in vitro experiments suggest that exosome activity follows deadenylation. In the exosome-mediated pathway, it appears that the short cap-containing mRNA fragments, remnants of the 3′ to 5′ exonucleolytic decay, are decapped by a scavenger activity, distinct from the deadenylation-dependent decapping activity (18,26,27).

In mammals, AU-rich instability elements (AREs), often located in the 3′ UTR of mRNAs that encode proto-oncogenes, cytokines, growth factors and transcription factors, enhance the rate of RNA turnover (28–32). Furthermore, experimentation in yeast demonstrated that AREs present in the TIF51A mRNA stabilized this transcript in glucose-rich medium and caused rapid mRNA decay in glucose-free medium (33). In this yeast study and in a HeLa cell-free system, the ARE also promoted deadenylation-dependent decapping of mRNA (21,33). ARE binding proteins that regulate mRNA decay rates have been identified in higher eukaryotic cells; they include those that stabilize mRNA (HuR) and those that destabilize mRNA (AUF1, tristetraprolin, KSRP) (27,31,32, 34–36). ARE binding proteins may function by promoting or preventing the exosome to the mRNA (27,34). Alternatively, ARE sequences within the mRNA may directly recruit exosomes (26).

Trypanosomatids are parasitic protozoa that are remarkable for their unusual mRNA metabolism. In the nucleus, long polycistronic mRNA, containing multiple and sequential open reading frames, are processed into translatable units by the addition of capped short leader RNAs and poly(A) tails. Within a single species, every mRNA is embellished at its 5′ end with the same 39 nt spliced leader (SL) sequence. Among species, SLs are similar and the conserved first four transcribed nucleotides are decorated with a complex of ribose and base methylations that are more extensive that those found in other organisms (37). However, the 5′ end of the SL is capped with a 7-methyl-guanosine moiety identical to that found in other eukarya. The role of the SL in mRNA metabolism is unknown.

In the absence of extensive transcriptional control of gene expression in trypanosomes, the predominant control of steady state mRNA levels is post-transcriptional (38–40). Differential mRNA stability appears to be controlled by sequences present in the 3′ UTR of the mRNA. For example, when the African trypanosome, Trypanosoma brucei, cycles through the tsetse fly, the parasite produces large quantities of proline-rich surface glycoproteins, called the EP/GPEET proteins (39,41). The 3′ UTR of EP/GPEET mRNAs contain specific cis-acting elements that directly contribute to the differential stability of each mRNA as the parasites migrate through compartments of the fly midgut (42). One element, a 26 nt interrupted uridine sequence, functions as an mRNA instability element as deletion of this region results in a marked increase in EP/GPEET mRNA half-life. Positive elements in the 3′ UTR of the EP/GREET mRNA that increase stability work with the 26mer element to precisely control EP/GREET levels throughout the parasite’s life cycle in both the tsetse fly and the bloodstream of the mammalian host. Recent work on expression of the major surface glycoproteins in the insect form of Leishmania chagasi parasites has uncovered differential mRNA stability elements (43). Deletion analysis of subregions within the 3′ UTR of the major surface glycoprotein mRNAs revealed both positive and negative elements. In the case of the Trypanosoma cruzi small mucin (SMUG) mRNA, an ARE in the 3′ UTR caused rapid mRNA turnover specifically in the infective trypomastigote stage of the parasite (44). The amastin mRNA in T.cruzi is differentially stabilized in epimastigote and amastigote organisms as a result of a ∼200 nt region within the 3′ UTR. The mechanisms that enable 3′ UTRs to contribute to differential mRNA stability are unknown.

Studies of mRNA decay in several eukaryotic systems suggest that differential mRNA turnover in trypanosomes most likely requires multiple RNA–protein interactions that serve to either stabilize or destabilize specific mRNAs in the cytoplasm (44–46). In two cases in trypanosomes, proteins that may contribute to mRNA turnover have been identified. In T.cruzi a 36 kDa RNA binding protein has been identified that binds to the amastin 3′ UTR and stabilized that mRNA in amastigote stage parasites (45). In T.brucei, an ortholog of the Rrp1 subunit of the yeast exosome exhibited 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity in an in vitro assay (47).

To dissect the major pathway(s) that regulate mRNA turnover in trypanosomatids we decided to undertake a biochemical approach to identify mRNA turnover activities that most probably exist within the trypanosome cytoplasm. Using cap-labeled in vitro synthesized RNA substrates and parasite S100 cytoplasmic extracts, we established a cell-free system from the trypanosome Leptomonas seymouri that contained three enzymatic activities that contribute to mRNA turnover. Interestingly, the trypanosome decapping activity specifically generates m7GDP, which makes it functionally similar to yeast Dcp1p/Dcp2. In addition to this decapping activity, we identified a cap scavenger activity that generates m7GMP. Cap scavenger activity likely plays a major role in exosome-mediated decay during mammalian mRNA turnover. Finally, a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity that is activated by an ARE was discovered. The stimulation of the exonucleolytic activity by an ARE demonstrated that the cell-free system contained constitutive as well as regulatory proteins that likely function in trypanosomes mRNA decay pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transcription templates and RNAs

RNAs were transcribed from DNA templates constructed as follows: two oligonucleotides containing the 39 nt SL RNA sequence from L.seymouri were used to amplify the 39 nt SL sequence from genomic DNA and add upstream a XmaI site, followed by an Sp6 promoter and a downstream SalI site. The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1, using the TOPO TA system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), to generate pSL-MCS. The SL-MCS A0 RNA was transcribed from this template after linearization at the HindIII site present within the multiple cloning site (MCS). The MCS A0 template was made by PCR amplification of the region between the 3′ end of the SL and the HindIII site of pSL-MCS. The upstream primer used for this PCR amplification contained an Sp6 promoter sequence. The MCS A0 RNA, transcribed from the MCS A0 template, was identical to the SL-MCS A0 RNA, except that it lacked the SL at its 5′ end. The pSL-MCS ARE was constructed by inserting a PCR-amplified 34 bp ARE sequence from TNF-α into the KpnI site of pSL-MCS. pSL-MCS ERA was made by insertion of the reverse complement TNF-α ARE into the KpnI site of pSL-MCS. The MCS ARE A0 template was prepared by PCR, using pSL-MCS ARE and the procedure described above to produce the MCS A0 template. The MCS A60 RNA, which contains a 3′ poly(A) tail, was synthesized using a ligation PCR approach (48). First, a recombinant construct was generated by ligation of HindIII-digested pSL-MCS to an A60-T60 homopolymer with HindIII compatible ends. Secondly, the A60-containing template was amplified by PCR using the M13 forward (GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT) and JM37 (GCCTACCTCGAGCACTC) primers that annealed to the sequences upstream from the SP6 promoter and downstream from the poly(A) sequence. After PCR amplification, the DNA was digested with SspI to remove the 3′ anchor sequence. The poly(G) tract-containing templates were generated by insertion of an 18 nt poly(G) tract between the BamHI and SpeI sites of pSL-MCS ARE and pSL-MCS ERA. The poly(G)-containing RNAs were digested as described above with HindIII prior to transcription. DNA templates for the 10 and 26 nt long RNAs were generated by digestion of pGEM 4 (Promega, Madison, WI) at the EcoRI or KpnI sites, respectively. All constructs were sequenced (Dr Robert Donnelly, UMDNJ-NJ Med Molecular Resource Facility).

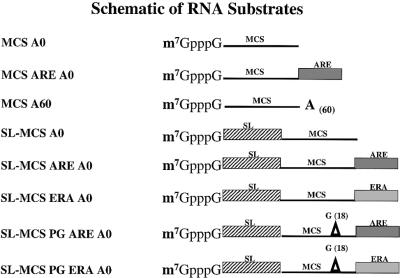

Internally labeled RNAs were synthesized in vitro with SP6 RNA polymerase and [α-32P]UTP using conditions described previously (49). RNAs were uniquely labeled at the γ-phosphate of the cap structure using [α-32P]GTP and recombinant vaccinia virus RNA triphosphatase, guanylyl transferase and RNA (guanine-N7) methyltransferase (50). Non-methylated RNA substrates were prepared as above in a cap-labeling reaction without S-adenosylmethionine. The labeled RNA was gel purified, adjusted to 50 000 c.p.m./µl and used in assays. RNA substrates are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A schematic of the RNA substrates used in this study. The MCS-labeled line is 64 nt and contains sequences from pCR2.1. The striped box is the L.seymouri 39 nt SL sequence. The ARE-labeled box is a 34 nt sequence and contains the ARE from the 3′ UTR of TNF-α mRNA. The ERA-labeled box is a 34 nt sequence that is the reverse complement of this sequence. The A(60) annotation represents 60 nt of adenylate residues. The triangle represents an 18 nt poly(G) tract inserted into the MCS sequence.

Cytoplasmic extracts

Leptomonas seymouri was grown as described previously (51). Cells were harvested at a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml, washed three times with PBS, and resuspended in 1.2 pellet volumes of LsCE buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.01% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 1 µM pepstatin, 1 µM leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF) (52). Parasites were disrupted using a 21-gauge needle and freeze-thawed three times. Extracts were precleared (11 000 g, 10 min, 4°C) and the supernatant was centrifuged (100 000 g, 1 h, 4°C) to yield an S100 fraction. Aliquots were quick-frozen and stored at –80°C.

Decapping reactions and NDP kinase assays

Reaction conditions were as described previously (21,53). Briefly, an 11 µl reaction contained 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 2.4 mM MgCl2, 20 mM KCl, 30 mM (NH4)2SO4, 4% glycerol, 4 µl cytoplasmic extract (40–80 µg protein) and 10–50 fmol RNA. Reactions proceeded for 30 min at 26°C and were terminated by the addition of 20 mM EDTA. Decapping products were separated on Bakerflex PEI-F-cellulose (Baker Corp., Phillipsburg, NJ) pre-run in deionized H2O and developed using 0.45 M (NH4)2SO4. Decapping efficiency was calculated using PhosphorImager-based quantitation of all radiolabeled molecular species. Percentages were determined by dividing m7GDP quantity by the total amount of radiolabel in each assay.

After 30 min, decapping reactions were increased to 100 µl with water, phenol:CHCl3 and then CHCl3-extracted, and then concentrated to 10 µl vol. ATP (1 mM) was added along with NDP kinase (Sigma, St Louis, MO). After 30 min at room temperature, reaction products were resolved by thin layer chromatography (TLC). Non-radiolabeled and radiolabeled standards were used to identity reaction products. Affinity purified, FLAG-tagged yeast Dcp1p was a kind gift from Carol Wilusz and Stuart Peltz. It was incubated using reaction conditions described above (53).

Two-dimensional TLC

Nucleotides were separated using the method of Bochner and Ames (54). Briefly, 11 µl of phenol:CHCl3 and CHCl3 extracted sample was spotted on the TLC plate and allowed to dry between each 3 µl aliquot. Plates were washed for 5 min in methanol, air-dried and developed in the first dimension using 1 M acetic acid, adjusted to pH 3.5 with ammonium hydroxide. Plates were washed for 20 min in methanol, air-dried and rotated 90° with respect to the first dimension before developing in the second dimension using saturated (NH4)2SO4 adjusted to pH 3.5 with H2SO4. Radioactive molecules were detected using PhosphorImager analysis.

RNA gel analysis

Internally labeled RNAs were incubated in Leptomonas cytoplasmic extracts as described for the decapping reactions. Incubations were terminated by adding 300 µl of HSCB (400 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 1% SDS and 1 mM EDTA). All reactions were phenol extracted and ethanol precipitated prior to separation on 7 M urea 5% polyacrylamide gels. RNAs were visualized and quantification was done using a PhosphorImager.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of two RNA decapping activities in trypanosomes

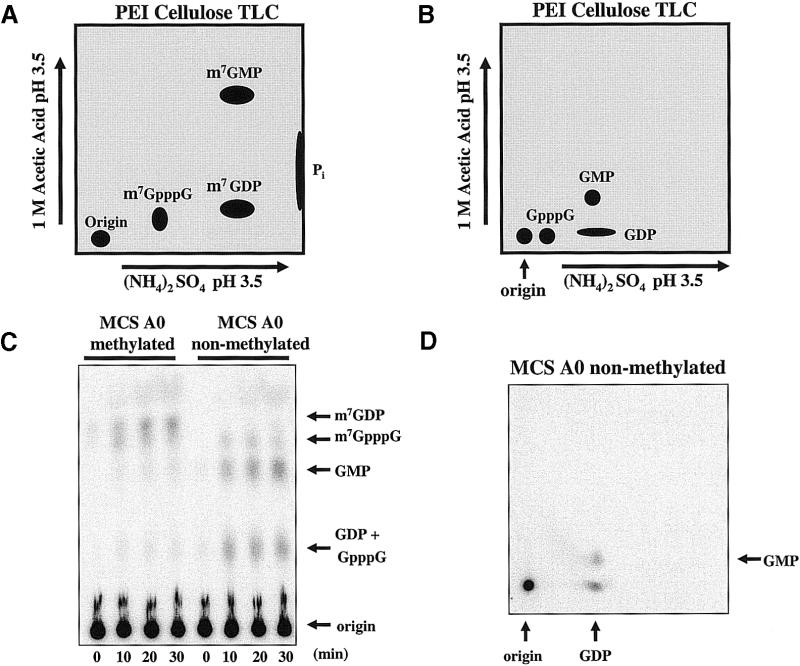

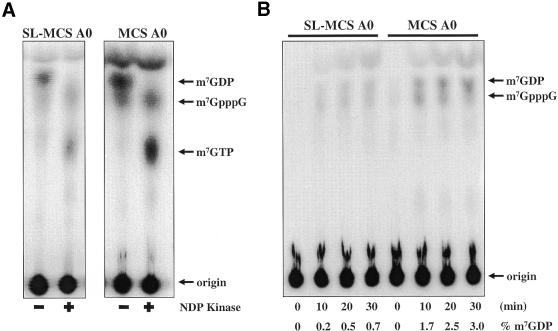

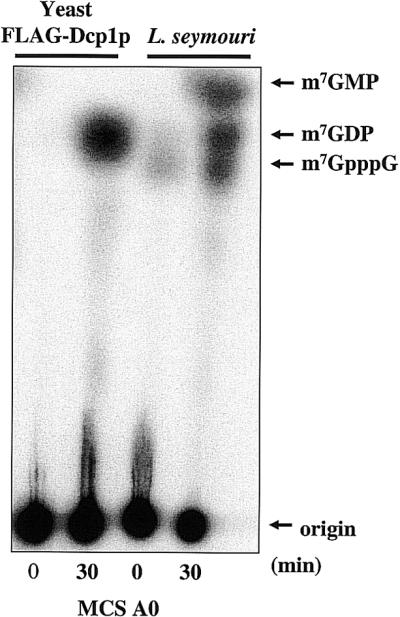

To initiate our search for a trypanosome decapping activity, we prepared in vitro transcribed RNAs labeled exclusively at the γ-phosphate of the 5′ cap. The cap was followed by a 64 nt RNA sequence derived from the MCS of the Invitrogen pCR 2.1 vector (Fig. 1). This substrate is similar to that used to dissect mRNA turnover pathways in mammalian cells and yeast (21,55). Incubation of trypanosome extracts with MCS A0 RNA generated three reaction products; one of these products co-migrated with m7GDP (Fig. 2). m7GDP is the molecular species released from cap-containing RNA by the yeast mRNA decapping enzyme (6), as shown in Figure 2. The other two reaction products migrated with m7GMP and m7GpppG. In mammalian cell-free systems, these products were derived from 3′ to 5′ exosome-mediated decay followed by a cap scavenger activity (18,47). Multiple independent experiments that utilized different trypanosome extract preparations yielded similar results (data not shown). The data indicate that trypanosomes, which comprise an ancient evolutionary branch of eukarya, share important RNA catabolic activities with higher eukaryotic organisms.

Figure 2.

Trypanosome cytoplasmic extracts contain an mRNA decapping activity. Extracts were incubated with [γ-32P]7-methyl-guanosine cap- labeled MCS A0 RNA (50 000 c.p.m.) in decapping buffer and resolved by one-dimensional TLC. The right two lanes show the reaction products after incubation in L.seymouri cytoplasmic extracts. The left two lanes show the reaction products when substrate was incubated with FLAG-tagged yeast Dcp1p. Non-radioactive nucleotides were included in the reactions as molecular markers. Reactions were phenol–chloroform extracted prior to spotting at the origin.

Our next set of experiments examined the specificity of the trypanosome decapping activities. Yeast Dcp1p/Dcp2p prefers to decap RNAs that are longer than 25 nt and possess a 7-methyl cap (14). To determine if a methylated cap is required for trypanosome decapping activity we incubated methylated and non-methylated RNAs in the cell-free extract. To bypass the limitations in resolution of the standard one-dimensional TLC system, we developed a two-dimensional TLC system that provides greater resolution of decapping reaction products. The two-dimensional TLC system resolves mono- and di-phosphorylated, methylated and unmethylated di-phosphorylated nucleosides, and inorganic phosphate (Pi) from all nucleotides. This effective separation allows for quantitative analysis of each radiolabeled reaction product. Figure 3A and B are diagrams of the migration of several small molecules, visualized by UV shadowing or autoradiography, using this TLC system. Figure 3C shows a time course of the incubation of methylated and non-methylated RNA in a trypanosome extract. m7GDP was released during a 30 min incubation with the methylated substrate. The major products released during incubation with the non-methylated substrate were GMP and GDP. The release of GMP and GDP after 15 min was confirmed by analysis using the two-dimensional TLC system (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Trypanosome mRNA decapping activity shows no preference for a m7G cap. (A) Diagram of a two-dimensional TLC that separates m7GDP from other methylated products. (B) Diagram of the separation of non-methylated products in the two-dimensional TLC assay. (C) A 30 min reaction of MCS A0 methylated at the 7′ position of the cap and MCS A0 that contains a non-methylated cap in Leptomonas cell-free extracts. (D) Two-dimensional TLC analysis of a 15 min reaction with MCS A0 non-methylated RNA.

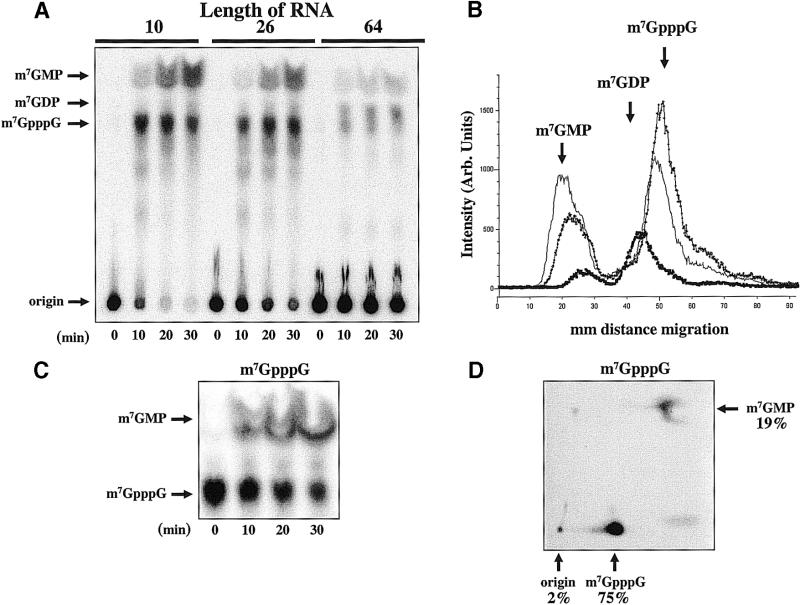

We then determined the substrate length specificity of the trypanosome decapping activity. Figure 4A shows decapping reactions that contained cap-labeled RNA substrates 10, 26 or 64 nt in length. m7GpppG and m7GMP were efficiently produced from the 10 and 26 nt long RNAs. In contrast, m7GDP was the major reaction product released from the 64 nt RNA substrate. Figure 4B is a graphic representation of the intensity of reaction products generated after 30 min and separated on the one-dimensional TLC shown in Figure 4A. The continuity curve confirms that the 10 and 26 nt RNAs produced mainly m7GMP and m7GpppG, with only minor m7GDP production. The 64 nt RNA produced one major peak consisting of m7GDP and minor amounts of m7GMP and m7GpppG. As short RNAs appeared to be substrates for a trypanosome activity that released m7GMP, we sought to determine if the cell-free system indeed contained a scavenger activity that could recognize m7GpppG (cap analog) and release m7GMP. Figure 4C shows a 30 min time course of the incubation of m7GpppG RNA with the Leptomonas cell-free extract. Incubation of m7GpppG in the extract resulted in robust scavenger activity. Separation of reaction products from a 15 min time point (Fig. 4C) confirmed the identity of the m7GpppG and m7GMP (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Influence of transcript length on mRNA decapping in trypanosome extracts. (A) Thirty minute time courses are shown for three different sized RNAs (10, 26 and 64 nt) using the one-dimension TLC assay. (B) A continuity plot of the intensity of decapping reaction signals seen in the 30 min reaction in (A). The peaks corresponding to the decapping reactions products are indicated. The squares contain data from the 64 nt RNA, the line labeled with the open diamonds contains data from the 26 nt RNA, and the undecorated line is from the 10 nt RNA. (C) A 30 min time course of free m7GpppG labeled at the γ position and incubated in cell-free extract. (D) The two-dimensional TLC separation of a 15 min reaction shown in (C).

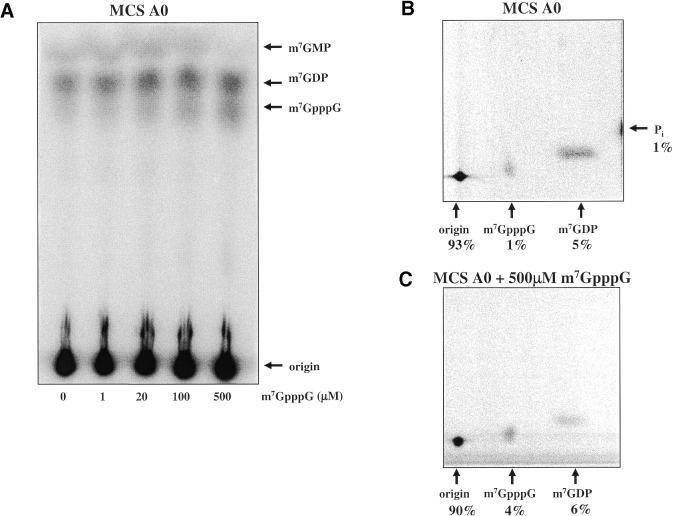

To further characterize the scavenger decapping activity we incubated MCS A0 RNA in the cell-free extract with increasing amounts of cap analog added in trans as competitor (Fig. 5A). Cap analog blocked the scavenger activity within the cap-labeled MCS A0 but did not affect the amount of m7GDP released by the trypanosome decapping activity. Figure 5B and C shows two-dimensional TLC analyses of the reaction products, generated after 30 min, in the presence or absence of 500 µM cap analog. Inclusion of 500 µM m7GpppG resulted in a 3-fold increase in the amount of detectable radiolabeled m7GpppG relative to m7GDP (4 versus 6% compared with 1 versus 5%) (compare Fig. 5B and C). Most importantly, Pi was no longer generated in the reaction (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that addition of excess unlabeled m7GpppG blocked a scavenger enzyme from recognizing radiolabeled m7GpppN and generating m7GMP that in turn could have been rapidly degraded to 7-methyl-guanosine and Pi by phosphatases present in the extract.

Figure 5.

The addition of free cap analog has minimal effects on Dcp1/Dcp2-like decapping activity in trypanosome extracts. (A) A titration of increasing amounts of m7GpppG added in trans to decapping reactions containing MCS A0 RNA and Leptomonas cell-free extract. (B) The separation of a 30 min reaction of MCS A0 using the two-dimension TLC system. (C) The separation of the products of a 30 min reaction of MCS A0 with 500 µM m7GpppG competitor added to cell-free extracts analyzed by the two-dimensional TLC system.

Influence of the 5′ SL-RNA sequence on decapping activity

As all mRNAs in trypanosomes contain a 39 nt SL at their 5′ end, we sought to determine if the trypanosome decapping activity could recognize the SL RNA sequence positioned adjacent to 5′ m7GpppG cap structure. The MCS A0 RNA and the SL-MCS A0 RNA, which differ only by the presence of the 39 nt SL RNA, were cap-labeled and incubated with trypanosome S100 extract (Fig. 6). The production of m7GDP was confirmed in this assay by converting it to m7GTP using NDP kinase (Fig. 6A). m7GTP migrates in a different area of the TLC plate than m7GpppG or Pi. Quantitation of a time course of decapping showed that the SL-MCS A0 RNA was decapped less efficiently than was the MCS A0 (Fig. 6B). The rate of decapping was linear for 30 min in both cases and was ∼4–6-fold slower for the SL RNA substrate. Therefore, capped RNAs that contain the SL sequence, normally found on the 5′ end of trypanosome mRNAs, were recognized as substrate by the trypanosome decapping enzyme. The decreased decapping rate of the SL RNA may reflect the highly structured nature of the SL sequence (56).

Figure 6.

The presence of a 5′ SL sequence reduces decapping efficiency. (A) One-dimensional TLC separation of decapping reaction products generated from RNAs with and without a 5′ SL sequence. Addition of NDP kinase to the reaction products (indicated as a ‘+’ sign) converted m7GDP to m7GTP. (B) One-dimensional TLC separation of products generated by time courses of cap-labeled RNAs with and without the 5′ SL sequence incubated in cytoplasmic extract.

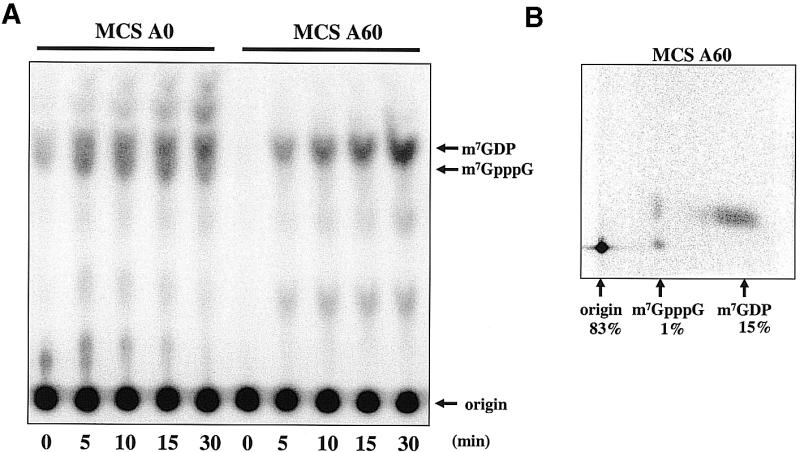

A poly(A) tail on the 3′ end of mRNA does not interfere with the decapping activity

We next investigated whether the trypanosome decapping activity was altered in the presence of a poly(A) tail. The potential for differential regulation exists since the mammalian and yeast decapping enzymes present in cytoplasmic extracts decap polyadenylated RNA poorly, perhaps due to the influence of cross talk between the 3′ end of the RNA and the 5′ cap (21,55). To test the effect of poly(A) tails on the trypanosome enzyme recognition of RNA, we assayed equivalent amounts of two RNAs that differed only by the presence of a poly(A) tail. A time course of decapping of the two substrates is shown in Figure 7A. Surprisingly, after a 30 min incubation, approximately three to four times the amount of m7GDP was removed from the poly(A)-containing RNA than from the control RNA (15 compared with 4% decapping; quantitated using the two-dimensional TLC assay) (Fig. 7B). In addition, a poly(A) tail at the 3′ end of the RNA protected the RNA from enzymatic activities that produced m7GpppG. We conclude that a poly(A) tail inhibits the 3′ to 5′ pathway of mRNA turnover and thus more RNA substrate is available for decapping by the Dcp1/Dcp2-like activity.

Figure 7.

A poly(A) tail did not inhibit decapping. (A) Trypanosome extracts were incubated with equal molar amounts of cap-labeled MCS A0 or MCS A60 RNA for 0 to 30 min. Analysis of reaction products was by one-dimensional TLC. (B) Two-dimensional TLC separation of 30 min decapping reaction products generated by incubation of MCS A60 cap-labeled RNA in cell-free extract. Quantification of reaction products generated by PhosphorImager analysis is included.

Trypanosomes contain a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity that is regulated by an ARE

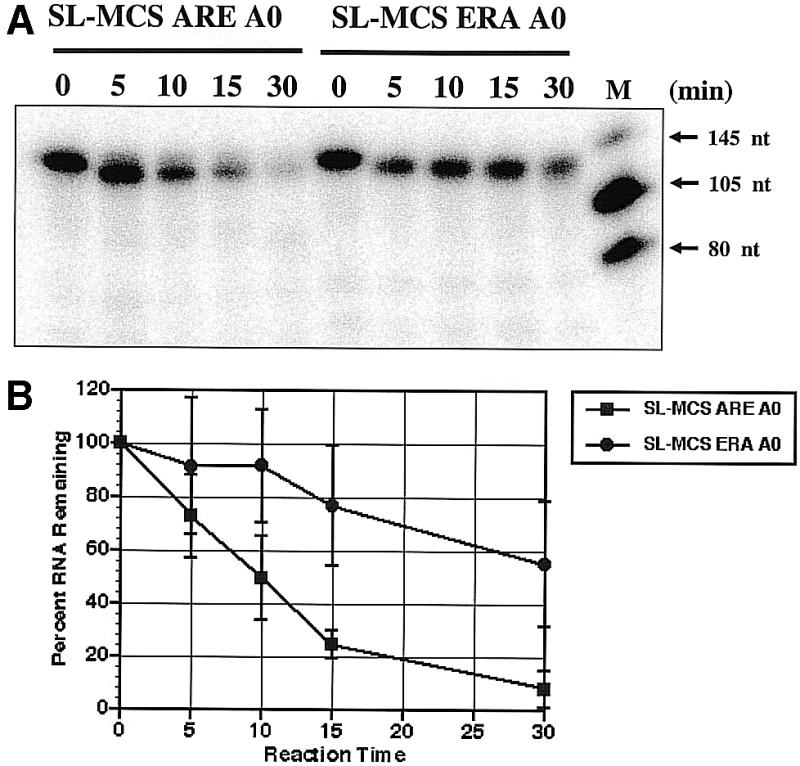

In mammalian cells and yeast, the cap scavenger activity most likely recognizes RNAs that have been significantly shortened at their 3′ end by the exonucleolytic activity of an exosome (18,57). We investigated the possibility that a similar exonuclease activity in the trypanosome extracts was generating shortened RNAs that served as substrate for the trypanosome scavenger activity. In mammalian cell-free systems, exosome-mediated 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activities are most active on RNAs that contain an ARE. Therefore, we utilized a pair of RNA substrates that differed only by the presence of an ARE. Both RNAs contained a cap, followed by an SL and a 64 nt sequence form the MCS of pCR 2.1 (see Fig. 1). Both RNAs lacked a poly(A) tail. The RNA containing the ARE is SL-MCS ARE A0; the RNA containing the 34 nt sequence from the complementary strand of the DNA fragment used to generate the ARE is SL-MCS ERA A0. Figure 8A shows time courses of the two internally labeled RNA templates incubated in the trypanosome S100 extract. The SL-MCS ERA A0 RNA was slowly degraded during a 30 min incubation. In sharp contrast, the SL-MCS ARE A0 RNA was rapidly degraded in the incubation and little RNA remained after 10 min. Quantitation of the loss of input RNA showed that the difference in decay rate was at least 4-fold (Fig. 8B). No decay intermediates were observed. We conclude that the presence of an ARE in the RNA stimulated a processive nuclease activity present in the extracts.

Figure 8.

ARE-stimulated decay of internally labeled RNA by trypanosome cytoplasmic extracts. (A) Incubation of SL-MCS ARE A0 RNA or SL-MCS ERA A0 RNA with extract for 0 to 30 min. Reaction products were analyzed on 7 M urea 5% polyacrylamide-denaturing gels. Size markers are included in the right lane of gel. (B) The data from three independent experiments were quantified and graphed to show RNA decay rates. The average percent RNA remaining following incubation in extract is plotted against incubation time. The error bars show one standard deviation. The boxes represent SL-MCS ARE A0 RNA data; the circles represent SL-MCS ERA A0 RNA data.

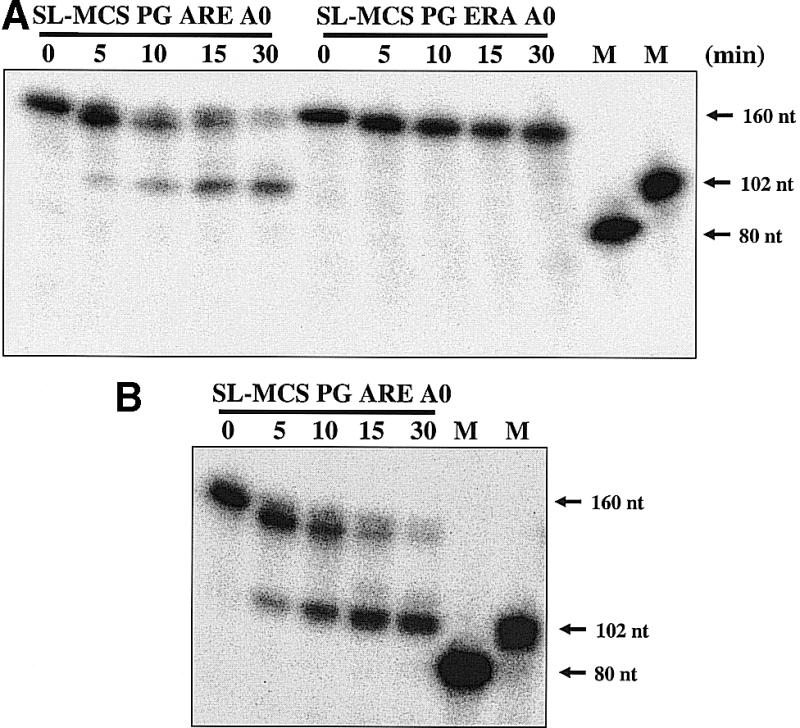

To determine if the activity was an exonuclease that worked in a 3′ to 5′ direction or a 5′ to 3′ direction, we paused RNA decay intermediates during the nuclease reaction. It has been reported previously in yeast, Chlamydomonas, and mammals that poly(G) tracts cause exonuclease activities to pause, allowing decay intermediates to be observed (58). We constructed two RNAs, SL-MCS PG ARE A0 and SL-MCS PG ERA A0, which contained an 18 nt poly(G) tract within the body of the RNA. The asymmetric position of the poly(G) tract within the RNA made it possible to determine the direction of decay by analyzing the size of the decay intermediates. A paused 5′ to 3′ exonuclease activity would have produced a 58 nt fragment, whereas a paused 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity would have yielded a 102 nt fragment. Figure 9A shows a time course of internally labeled SL-MCS PG ARE A0 RNA incubated with extract. A 102 nt decay intermediate was observed, consistent with a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity acting on the ARE-containing RNA. The SL-MCS PG ERA A0 RNA was stable during the 30 min incubation, as observed for the non-poly(G)-containing RNA (see Fig. 8). Cap-labeled SL-MCS PG ARE A0 RNA produced the same intermediate as internally labeled RNA (Fig. 9B). These results demonstrate that an ARE-stimulated 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity is present in trypanosome extracts.

Figure 9.

A 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity is activated by an ARE. (A) Internally labeled RNAs, containing an 18 nt poly(G) tract, were incubated in Leptomonas cytoplasmic extract for 0–30 min and analyzed on a 7 M urea 5% polyacrylamide-denaturing gel. Only reactions that contained the SL-MCS ARE A0 RNA yielded a 102 nt decay intermediate. (B) A time course of decapping of SL-MCS PG ARE A0 labeled at the γ-phosphate of the cap (m7G32pppN) and analyzed on a 7 M urea 5% polyacrylamide-denaturing gel. The cap-labeled RNA was degraded to a 102 nt product upon incubation in Leptomonas cytoplasmic extract. Markers are in vitro transcripts generated from templates digested 5′ or 3′ to the poly(G) tract.

Decapping of ARE-containing RNAs

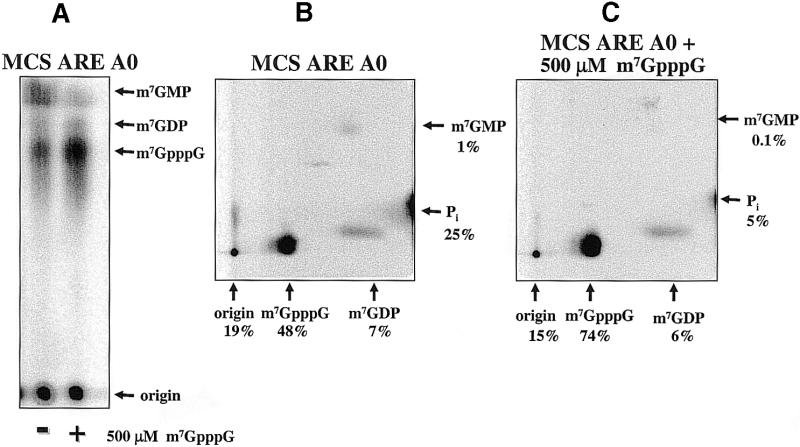

In mammalian cell-free systems, exonuclease activity, mediated by the exosome, may be coupled with cap scavenger activity in RNA decay pathways (18). We therefore determined if ARE-containing RNAs were decapped more efficiently than control substrates in the trypanosome cell-free system. First, we determined the amount of m7GDP released from MCS A0 and MCS ARE A0 RNAs. The amount of m7GDP released from the two RNAs was slightly different (compare MCS A0 RNA in Figs 6A and 10A for the one-dimensional TLC analysis; Figs 5B and 10B show the two-dimensional analysis). Quantitation of the data shown in Figures 5B and 10B indicate a 5 and 7% release of m7GDP, respectively. In contrast, m7GpppG released from the ARE-containing RNA was significantly more than m7GpppG released from the RNA that lacked the ARE (48 versus 1%). The increase in m7GpppG released from the ARE-containing substrate was most likely the result of the stimulated 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity observed in Figure 9.

Figure 10.

The cap scavenger activity functions to metabolize the m7GpppG generated from the ARE-stimulated 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity. (A) One- dimensional TLC analysis of cap-labeled MCS ARE A0 RNA after a 30 min incubation in Leptomonas cytoplasmic extract. The right lane shows reaction products generated when 500 µM m7GpppG was included in the assay. (B) Two-dimensional analysis of the reaction products generated by incubation of cap-labeled MCS ARE A0 RNA in extract. (C) Two-dimensional analysis of the reaction products generated by extract incubated with MCS ARE A0 RNA in the presence of 500 µM m7GpppG. Quantification was determined by PhosphorImager analysis.

We then determined if the cap scavenging activity could degrade the m7GpppG generated in the nuclease reaction. Indeed, excess unlabeled m7GpppG blocked the metabolism of radiolabeled m7GpppG to m7GMP, and ultimately to Pi and 7-methyl-guanosine, by serving as substrate for the cap scavenging activity (Fig. 10). Addition of 500 µM m7GpppG to the MCS ARE A0 RNA resulted in a 1.5-fold increase in production of m7GpppG (from 48 to 74%), a 10-fold decrease in m7GMP (from 1 to 0.1%) and a 5-fold decrease in Pi (25 to 5%). These data are consistent with a decay pathway in which an ARE-stimulated 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity yields m7GpppG which is then rapidly catabolized by a cap scavenging activity in the cytoplasm of trypanosomes.

DISCUSSION

We have succeeded in identifying three trypanosome enzymatic activities that function in vitro to metabolize mRNA. This is the first demonstration of a decapping activity and a cap scavenging activity in trypanosomes. Moreover, the differential recognition of ARE-containing RNAs by a 3′ to 5′ exonucleolytic activity demonstrates that the in vitro system recapitulates a substrate recognition pattern reminiscent of that found in mammalian cells. By establishing in vitro mRNA decapping and regulated RNA decay assays using trypanosome cytoplasmic extracts, we have developed a powerful tool for investigating mRNA turnover in these parasites.

Initially, we used a one-dimensional TLC system to determine if the S100 extracts decapped synthetic RNA substrates. However, we found that the one-dimensional TLC system commonly used to follow decapping reactions in other systems did not adequately separate the reaction products. We addressed this problem using two additional analytical methods. The NDP kinase reaction specifically converted m7GDP to m7GTP and the two-dimensional TLC system separated m7GDP from all other radiolabeled small molecules. These reactions unequivocally identify m7GDP as a product of the decapping reaction using the trypanosome extract. The production of m7GDP demonstrated that trypanosomes contain a decapping activity that is functionally equivalent to the yeast Dcp1/Dcp2p enzyme. The dependence of both enzymes on Mg2+ for activity is an additional similarity. Both yeast Dcp1p/Dcp2p and the trypanosome activity recognized the 5′ cap in the context of its associated RNA and are more active on RNAs 25 nt or longer (14). In contrast to yeast Dcp1/ Dcp2, the trypanosome activity behaved differently from the yeast enzyme in two ways. First, the trypanosome enzyme more efficiently recognized non-methylated caps than did the yeast enzyme. Secondly, the trypanosome activity was slightly stimulated when the RNA contained a 3′ poly(A) tail. In yeast, Dcp1/Dcp2-dependent decapping of poly(A) tailed RNA is inhibited due to cap protection by protein–RNA interactions that effectively circularize the mRNA (1). This circularization requires Pabp interaction with the poly(A) tail as well as cap binding proteins and translation factors (59). It is possible that the trypanosome in vitro system lacks specific RNA binding proteins that interact with the poly(A) tail and sequester the cap away from the decapping machinery. A Pabp protein has been identified in Leishmania (60) and antibodies generated against the Leishmania Pabp recognize a protein present in L.seymouri extracts (our unpublished observations). However, our finding that poly(A) tails did not block decapping in our assays may be explained by limiting amounts of Pabp1 and/or the absence of any associated proteins that are required for an inhibition of decapping. Alternatively, the increase in m7GDP could simply be the result of the poly(A)-dependent inhibition of the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity, which would leave more substrate available for the decapping activity. Ultimately, it is possible that regulation of mRNA turnover in the trypanosome cytoplasm may differ from that found in yeast and mammals.

The trypanosome Dcp1/Dcp2-like activity identified in this work was slightly affected by RNA sequence variations since the SL RNA sequence altered the efficiency of the decapping reaction. It was not surprising as we expect that the SL sequence, common to all trypanosome mRNAs, should influence the binding of a decapping enzyme complex. Quite possibly, decapping rates may be affected by the combination of the SL linked to actual 5′ UTR and/or 3′ UTR sequences and/or contain the hypermethylated bases contained with a cap 4 structure. These possibilities are currently being pursued.

We uncovered a second type of decapping activity in the trypanosome cell-free system. This activity is similar to the cap scavenger activity found in mammalian cells and yeast extracts (18). The cap scavenger activity called DcpS in mammalian cells recognizes m7GpppG as substrate and yields m7GMP; m7GMP is likely unstable in crude extracts and may be readily converted to 7-methyl guanosine and Pi by phosphatases. Using the two-dimensional TLC system we were able to monitor Pi production and thus, indirectly, cap scavenger activity. Excess unlabeled m7GpppG added to the reaction caused a decrease in Pi, indicating that the trypanosome scavenger activity recognized this RNA as substrate.

In human cells, RNA turnover pathways have not been clearly mapped, although evidence for deadenylation and decapping of mRNAs suggests that these activities can contribute to the decay process (18,21,27). Mammalian cell extracts contain two distinct decapping activities; one is the Dcp1/Dcp2-like and removes m7GDP from the 5′ end of capped RNAs, the other is the DcpS activity (18,21). DcpS likely recognizes cap-containing RNA fragments produced by exosome-mediated degradation of the body of the mRNA. Our experiments suggest that trypanosomes also contain these two types of decapping activities. The data suggest evolutionarily conserved mechanisms for mRNA turnover among primitive protozoa and more advanced metazoan organisms.

mRNA degradation in trypanosomes must require enzymes that unblock the 5′ cap, and possibly the 3′ poly(A) tail, and expose the RNA to exonuclease and endonuclease activities (45,61–64). Our identification of two decapping activities has uncovered what are likely to be primary components of the mRNA turnover machinery in these organisms. In addition, our identification of ARE-mediated 3′ to 5′ RNA turnover correlates with the discovery of exosome subunit orthologs in T.brucei (47). In higher eukaryotes, exosome components and ARE binding proteins facilitate the decay of ARE-containing mRNAs (18,26,27,65). ARE-mediated decay is a mechanism used in these organisms to modulate differential mRNA turnover in response to cell cycle events, viral infection and cellular differentiation (6). Several trypanosome mRNAs have been shown to contain AREs within their 3′ UTRs (44). In addition, the 3′ UTRs of other trypanosome mRNAs contain subregions that affect mRNA stability differentially during the parasite’s life cycle (39,41,43,66). It remains to be determined if the trypanosome exosome is involved in the ARE-stimulated mRNA decay identified in the trypanosome cell-free system.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Barry Bochner for his instruction on the two-dimensional TLC analysis. We thank Gwen Gilinger and Elizabeth Bates for critical reading of the manuscript and for antibodies. V.B. is supported by the National Institutes of Health grant AI29478. J.W. is supported by the National Institutes of Health grants GM63832 and CA80062. V.B. is a Burroughs Wellcome New Investigator in Molecular Parasitology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitchell P. and Tollervey,D. (2001) mRNA turnover. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 13, 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilusz C.J., Wormington,M. and Peltz,S.W. (2001) The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol., 2, 237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross J. (1995) mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Microbiol. Rev., 59, 423–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caponigro G. and Parker,R. (1996) mRNA turnover in yeast promoted by the MATα1 instability element. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 4304–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korner C.G., Wormington,M., Muckenthaler,M., Schneider,S., Dehlin,E. and Wahle,E. (1998) The deadenylating nuclease (DAN) is involved in poly(A) tail removal during the meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 17, 5427–5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tucker M. and Parker,R. (2000) Mechanisms and control of mRNA decapping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 571–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy J.E. (1998) Posttranscriptional control of gene expression in yeast. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 62, 1492–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daugeron M.C., Mauxion,F. and Seraphin,B. (2001) The yeast POP2 gene encodes a nuclease involved in mRNA deadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 2448–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker M., Staples,R.R., Valencia-Sanchez,M.A., Muhlrad,D. and Parker,R. (2002) Ccr4p is the catalytic subunit of a Ccr4p/Pop2p/Notp mRNA deadenylase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J., 21, 1427–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J., Chiang,Y.C. and Denis,C.L. (2002) CCR4, a 3′–5′ poly(A) RNA and ssDNA exonuclease, is the catalytic component of the cytoplasmic deadenylase. EMBO J., 21, 1414–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker M., Valencia-Sanchez,M.A., Staples,R.R., Chen,J., Denis,C.L. and Parker,R. (2001) The transcription factor associated Ccr4 and Caf1 proteins are components of the major cytoplasmic mRNA deadenylase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell, 104, 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boeck R., Tarun,S.,Jr, Rieger,M., Deardorff,J.A., Muller-Auer,S. and Sachs,A.B. (1996) The yeast Pan2 protein is required for poly(A)-binding protein-stimulated poly(A)-nuclease activity. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beelman C.A., Stevens,A., Caponigro,G., LaGrandeur,T.E., Hatfield,L., Fortner,D.M. and Parker,R. (1996) An essential component of the decapping enzyme required for normal rates of mRNA turnover. Nature, 382, 642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaGrandeur T.E. and Parker,R. (1998) Isolation and characterization of Dcp1p, the yeast mRNA decapping enzyme. EMBO J., 17, 1487–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decker C.J. and Parker,R. (1993) A turnover pathway for both stable and unstable mRNAs in yeast: evidence for a requirement for deadenylation. Genes Dev., 7, 1632–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.vanHoof A. and Parker,R. (1999) The exosome: a proteasome for RNA? Cell, 99, 347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler J.S. (2002) The yin and yang of the exosome. Trends Cell Biol., 12, 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z. and Kiledjian,M. (2001) Functional link between the mammalian exosome and mRNA decapping. Cell, 107, 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frischmeyer P.A., van Hoof,A., O’Donnell,K., Guerrerio,A.L., Parker,R. and Dietz,H.C. (2002) An mRNA surveillance mechanism that eliminates transcripts lacking termination codons. Science, 295, 2258–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilleren P. and Parker,R. (1999) Mechanisms of mRNA surveillance in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet., 33, 229–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao M., Wilusz,C.J., Peltz,S.W. and Wilusz,J. (2001) A novel mRNA-decapping activity in HeLa cytoplasm is regulated by AU-rich elements. EMBO J., 20, 1134–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Astrom J., Astrom,A. and Virtanen,A. (1992) Properties of a HeLa cell 3′ exonuclease specific for degrading poly(A) tails of mammalian mRNA. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 18154–18159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korner C. and Wahle,E. (1997) Poly(A) tail shortening by a mammalian poly(A)-specific 3′-exoribonuclease. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 10448–10456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao M., Fritz,D.T., Ford,L.P. and Wilusz,J. (2000) Interaction between a poly(A)-specific ribonuclease and the 5′ cap influences mRNA deadenylation rates in vitro. Mol. Cell, 5, 479–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dehlin E., Wormington,M., Korner,C.G. and Wahle,E. (2002) Cap-dependent deadenylation of mRNA. EMBO J., 19, 1079–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukherjee D., Gao,M., O’Connor,P., Raijmakers,R., Pruijn,G., Lutz,C. and Wilusz,J. (2002) The mammalian exosome mediates the efficient degradation of mRNAs that contain AU-rich elements. EMBO J., 21, 165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C.Y., Gherzi,R., Ong,S.E., Chan,E.L., Raijmakers,R., Pruijn,G.J., Stoecklin,G., Moroni,C., Mann,M. and Karin,M. (2001) AU binding proteins recruit the exosome to degrade ARE-containing mRNAs. Cell, 107, 451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw G. and Kamen,R. (1986) A conserved AU sequence from the 3′ untranslated region of GM-CSF mRNA mediates selective mRNA degradation. Cell, 46, 659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma W.J., Chung,S. and Furneaux,H. (1997) The Elav-like proteins bind to AU-rich elements and to the poly(A) tail of mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3564–3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C.Y. and Shyu,A.B. (1995) AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci., 20, 465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan X.C. and Steitz,J.A. (1998) Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J., 17, 3448–3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng S.S., Chen,C.Y., Xu,N. and Shyu,A.B. (1998) RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J., 17, 3461–3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vasudevan S. and Peltz,S.W. (2001) Regulated ARE-mediated mRNA decay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell, 7, 1191–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ford L.P., Watson,J., Keene,J.D. and Wilusz,J. (1999) ELAV proteins stabilize deadenylated intermediates in a novel in vitro mRNA deadenylation/degradation system. Genes Dev., 13, 188–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai W.S., Carballo,E., Strum,J.R., Kennington,E.A., Phillips,R.S. and Blackshear,P.J. (1999) Evidence that tristetraprolin binds to AU-rich elements and promotes the deadenylation and destabilization of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 4311–4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loflin P., Chen,C.Y. and Shyu,A.B. (1999) Unraveling a cytoplasmic role for hnRNP D in the in vivo mRNA destabilization directed by the AU-rich element. Genes Dev., 13, 1884–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bangs J.D., Crain,P.F., Hashizume,T., McCloskey,J.A. and Boothroyd,J.C. (1992) Mass spectrometry of mRNA cap 4 from trypanosomatids reveals two novel nucleosides. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 9805–9815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanhamme L. and Pays,E. (1995) Control of gene expression in trypanosomes. Microbiol. Rev., 59, 223–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clayton C.E. (2002) Life without transcriptional control? From fly to man and back again. EMBO J., 21, 1881–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hotz H.R., Biebinger,S., Flaspohler,J. and Clayton,C. (1998) PARP gene expression: control at many levels. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 91, 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roditi I. and Liniger,M. (2002) Dressed for success: the surface coats of insect-borne protozoan parasites. Trends Microbiol., 10, 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vassella E., Den Abbeele,J.V., Butikofer,P., Renggli,C.K., Furger,A., Brun,R. and Roditi,I. (2000) A major surface glycoprotein of Trypanosoma brucei is expressed transiently during development and can be regulated post-transcriptionally by glycerol or hypoxia. Genes Dev., 14, 615–626. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myung K.S., Beetham,J.K., Wilson,M.E. and Donelson,J.E. (2002) Comparison of the post-transcriptional regulation of the mRNAs for the surface proteins PSA (GP46) and MSP (GP63) of Leishmania chagasi. J. Biol. Chem., 20, 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiNoia J.M., D’Orso,I., Sanchez,D.O. and Frasch,A.C. (2000) AU-rich elements in the 3′-untranslated region of a new mucin-type gene family of Trypanosoma cruzi confers mRNA instability and modulates translation efficiency. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 10218–10227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coughlin B.C., Teixeira,S.M., Kirchhoff,L.V. and Donelson,J.E. (2000) Amastin mRNA abundance in Trypanosoma cruzi is controlled by a 3′-untranslated region position-dependent cis-element and an untranslated region-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 12051–12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hotz H.R., Hartmann,C., Huober,K., Hug,M. and Clayton,C. (1997) Mechanisms of developmental regulation in Trypanosoma brucei: a polypyrimidine tract in the 3′-untranslated region of a surface protein mRNA affects RNA abundance and translation. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3017–3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Estevez A.M., Kempf,T. and Clayton,C. (2001) The exosome of Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J., 20, 3831–3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ford L.P. and Wilusz,J. (1999) An in vitro system using HeLa cytoplasmic extracts that reproduces regulated mRNA stability. Methods, 17, 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilusz J. and Shenk,T. (1988) A 64 kDa nuclear protein binds to RNA segments that include the AAUAAA polyadenylation motif. Cell, 52, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shuman S. (2001) Structure, mechanism and evolution of the mRNA capping apparatus. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 66, 1–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luo H. and Bellofatto,V. (1997) Characterization of two protein activities that interact at the promoter of the trypanosomated Spliced Leader RNA. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 33344–33352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robertson C.D. (1999) The Leishmania mexicana proteasome. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 103, 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang S., Williams,C.J., Wormington,M., Stevens,A. and Peltz,S.W. (1999) Monitoring mRNA decapping activity. Methods, 17, 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bochner B.R. and Ames,B.N. (1982) Complete analysis of cellular nucleotides by two-dimensional thin layer chromatography. J. Biol. Chem., 257, 9759–9769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilusz C.J., Gao,M., Jones,C.L., Wilusz,J. and Peltz,S.W. (2001) Poly(A)-binding proteins regulate both mRNA deadenylation and decapping in yeast cytoplasmic extracts. RNA, 7, 1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harris K.A.J., Crothers,D.M. and Ullu,E. (1995) In vivo structural analysis of spliced leader RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei and Leptomonas collosoma: a flexible structure that is independent of cap4 methylations. RNA, 1, 351–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nuss D.L., Furuichi,Y., Koch,G. and Shatkin,A.J. (1975) Detection in HeLa cell extracts of a 7-methyl guanosine specific enzyme activity that cleaves m7GpppNm. Cell, 6, 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ross J. (1999) Assays for analyzing exonucleases in vitro. Methods, 17, 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wells S.E., Hillner,P.E., Vale,R.D. and Sachs,A.B. (1998) Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol. Cell, 2, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bates E.J., Knuepfer,E. and Smith,D.F. (2000) Poly(A)-binding protein I of Leishmania: functional analysis and localisation in trypanosomatid parasites. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1211–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beetham J.K., Myung,K.S., McCoy,J.J., Wilson,M.E. and Donelson,J.E. (1997) Glycoprotein 46 mRNA abundance is post-transcriptionally regulated during development of Leishmania chagasi promastigotes to an infectious form. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 17360–17366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burchmore R.J. and Landfear,S.M. (1998) Differential regulation of multiple glucose transporter genes in Leishmania mexicana. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 29118–29126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Y., El Fakhry,Y., Sereno,D., Tamar,S. and Papadopoulou,B. (2000) A new developmentally regulated gene family in Leishmania amastigotes encoding a homolog of amastin surface proteins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 110, 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hug M., Carruthers,V.B., Hartmann,C., Sherman,D.S., Cross,G.A. and Clayton,C. (1993) A possible role for the 3′-untranslated region in developmental regulation in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 61, 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guhaniyogi J. and Brewer,G. (2001) Regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Gene, 265, 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mahmood R., Hines,J.C. and Ray,D.S. (1999) Identification of cis and trans elements involved in the cell cycle regulation of multiple genes in Crithidia fasciculata. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 6174–6182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]