Abstract

Bloom’s syndrome (BS) is a disorder associated with chromosomal instability and a predisposition to the development of cancer. The BS gene product, BLM, is a DNA helicase of the RecQ family that forms a complex in vitro and in vivo with topoisomerase IIIα. Here, we show that BLM stimulates the ability of topoisomerase IIIα to relax negatively supercoiled DNA. Moreover, DNA binding analyses indicate that BLM recruits topoisomerase IIIα to its DNA substrate. Consistent with this, a mutant form of BLM that retains helicase activity, but is unable to bind topoisomerase IIIα, fails to stimulate topoisomerase activity. These results indicate that a physical association between BLM and topoisomerase IIIα is a prerequisite for their functional biochemical interaction.

INTRODUCTION

Bloom’s syndrome (BS) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by proportional dwarfism, immunodeficiency, male infertility and a greatly elevated incidence of cancers of most types (reviewed in 1). This predisposition to cancer is thought to arise from the inherent genomic instability that is a feature of BS cells. In particular, BS cells display an elevated level of genetic recombination that is manifested as an increase in the frequency of both sister chromatid exchanges and interchromosomal homologous recombination events (2).

The gene mutated in BS, BLM, encodes a protein of molecular mass 159 kDa that belongs to the RecQ family of DNA helicases (3). BLM protein has been purified and shown to act as a 3′→5′ DNA helicase on a variety of different DNA substrates (4–8). Mutations in two other genes encoding RecQ helicases are also associated with human cancer-prone disorders. WRN is defective in Werner’s syndrome and RECQ4 is defective in Rothmund–Thomson syndrome (9,10). Members of the RecQ helicase family contain a highly conserved catalytic helicase domain that is flanked by domains that vary both in size and sequence between different family members. However, despite this apparent sequence divergence in those regions outside the helicase domain, all known mutants lacking a RecQ helicase display genomic instability (reviewed in 11–13). Moreover, many of these mutants display a hyper-recombinogenic phenotype reminiscent of BS cells, suggesting that RecQ helicases perform a conserved function in controlling the level of homologous recombination in cells (14–19). Although the precise cellular role of any RecQ helicase has yet to be elucidated, several lines of evidence suggest that RecQ helicases act in concert with type IA topoisomerases (reviewed in 20).

The type IA subclass of topoisomerases includes Escherichia coli topoisomerases I and III and the eukaryotic topoisomerase III enzymes (reviewed in 21). In vertebrates, there are at least two isoforms of topoisomerase III, termed α and β, which display only a weak topoisomerase activity towards negatively supercoiled DNA (22–25). Yeast cells express a single topoisomerase III enzyme encoded by the TOP3 gene (26). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, top3Δ mutants are viable, but grow very slowly and have defects in S phase responses to DNA damage and in both mitotic and meiotic recombination (16,26–28). In contrast, the top3+ gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is essential for viability, with top3Δ mutants displaying an inability to accurately segregate daughter chromosomes during mitosis (29,30). Interestingly, mutation of SGS1 or rqh1+, the sole RecQ homologues found in budding and fission yeast, respectively, can suppress the deleterious effects caused by the absence of Top3 protein (16,28–30). One interpretation of this conserved genetic interaction is that RecQ helicases act upstream of topoisomerase III in the same biochemical pathway and that RecQ helicases generate a DNA structure that requires resolution by topoisomerase III (reviewed in 20). Consistent with this proposal, E.coli RecQ can convert negatively supercoiled plasmid DNA to a structure [as yet not defined, but presumed to be single-stranded (ss)DNA] that can be acted upon by E.coli or S.cerevisiae Top3p to generate catenated DNA molecules (31).

The S.cerevisiae Sgs1 and Top3 proteins also interact physically, raising the possibility that Sgs1p may recruit Top3p to its site of action (16,32,33). We and others have demonstrated that BLM and human topoisomerase IIIα (hTOPO IIIα) are tightly associated in human cells (34–36) and that the two purified proteins interact in vitro (35), indicating that this association is a direct one.

In this study, we demonstrate that BLM can stimulate the topoisomerase activity of hTOPO IIIα. In contrast, a mutant BLM protein that is catalytically active, but no longer able to interact with hTOPO IIIα, has lost the ability to stimulate hTOPO IIIα protein. Moreover, we provide evidence that hTOPO IIIα associates with a BLM–DNA complex. These data are consistent with the notion that hTOPO IIIα is recruited to its site of action through a direct interaction with the BLM helicase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA substrates

The φX174 helicase substrate was generated by annealing a 21mer oligonucleotide (GTGCATATACCTGGTCTTTCG) to circular φX174 ssDNA before being extended by 4 nt in the presence of Klenow polymerase, dATP, dTTP and [α-32P]dCTP. G-quadruplex (G4) DNA representing the murine immunoglobulin Sγ2B switch region and the 12 nt bubble-containing duplex were prepared using the oligonucleotides and experimental conditions described previously (6,7). Topoisomerase assays (see below) were performed on negatively supercoiled (form I) φX174 DNA.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

Plasmids driving the expression of either hexahistidine-tagged BLM or BLM-NC have been described previously (4,35). Purification of these proteins from yeast was as described by Karow et al. (4). Relative specific helicase activities of both proteins were determined using the partially double-stranded φX174 DNA substrate described above. Recombinant hTOPO IIIα was a kind gift of Drs Jean-François Riou and Hélène Goulaouic (Aventis Pharma, France). Human RPA was a kind gift of Dr Rick Wood (University of Pittsburgh). Escherichia coli SSB was purchased from Promega.

Far-western analysis

Protein–protein interactions between hTOPO IIIα and the BLM or BLM-NC proteins were tested as described previously (35).

Helicase assays

Unwinding of various DNA substrates by BLM and BLM-NC were performed using the reaction conditions described by Karow et al. (4)

Topoisomerase assays

Typically, BLM (120 nM) and hTOPO IIIα (300 nM) were incubated with 200 ng of negatively supercoiled φX174 in the presence of either human RPA (350 ng) or E.coli SSB (1.5 µg) in 30 µl of reaction buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 µg/ml BSA, 40 mM NaCl, 0.2 U creatine kinase, 6 mM phosphocreatine and 1 mM DTT). In experiments comparing BLM and BLM-NC, protein preparations were diluted to give equivalent specific activities. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 5 mM ATP, followed by incubation at 37°C. Aliquots of 5 µl were taken at the indicated times and 1 µl of 5× STOP buffer (250 mM EDTA, 5% SDS, 5 mg/ml proteinase K) was added. Samples were then incubated at 37°C for a further 10 min to deproteinise the DNA. The DNA was separated on 0.6% agarose gels in the absence of ethidium bromide, before being transferred to nylon filters by conventional Southern blotting and then hybridised to a random-primed labeled φX174 DNA probe using Rediprime (Amersham). Visualisation and quantification of reaction products were performed using a PhosphorImager 840 (Molecular Dynamics) and ImageQuant software.

Gel mobility shift assays

Typically, BLM (300 nM) and hTOPO IIIα (100–900 nM) were incubated together with the labeled bubble-containing duplex substrate in 30 µl of reaction buffer (20 mM triethanolamine–HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 µg/ml BSA, 40 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 5 mM ATPγS). Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 25 min. Protein–DNA complexes were fixed by the addition of 0.25% glutaraldehyde and incubation at 37°C for 10 min, before electrophoresis through a native 5% polyacrylamide gel in TBE buffer.

RESULTS

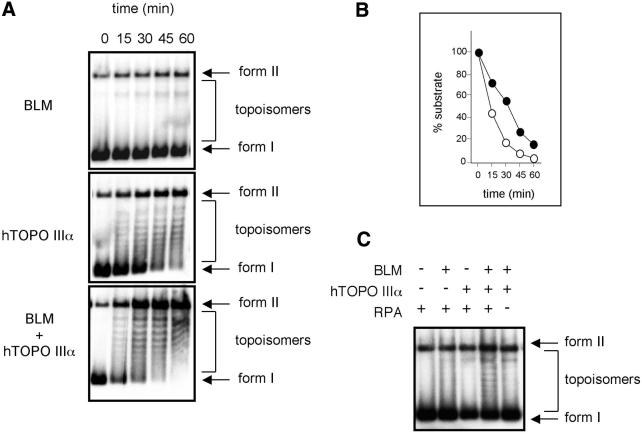

BLM can stimulate the activity of hTOPO IIIα

To examine a possible functional role for the interaction of the BLM and hTOPO IIIα proteins, we investigated whether BLM had any effect on the ability of hTOPO IIIα to act upon negatively supercoiled φX174 DNA. When hTOPO IIIα was incubated with supercoiled φX174 DNA in the absence of BLM, form I DNA disappeared with the concomitant appearance of topoisomers. At longer incubation periods, fully relaxed DNA (form II) was also evident. It is possible that a proportion of form II DNA molecules also represented nicked DNA since Top3β from Drosophila melanogaster has been shown to introduce single-stranded nicks into negatively supercoiled DNA (see Discussion). Given the potential heterogeneity of the reaction products generated by hTOPO IIIα, we quantified the loss of form I DNA as an indication of hTOPO IIIα activity and found that co-incubation with BLM led to an approximate doubling in the rate of hTOPO IIIα activity (Fig. 1A and B). Incubation of BLM alone with the φX174 substrate had no effect on the level of form I DNA, indicating that the BLM preparation did not contain any contaminating topoisomerase activity (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

BLM stimulates the activity of hTOPO IIIα. (A) Time course showing the relaxation of supercoiled φX174 DNA in the presence of 120 nM BLM alone (top), 300 nM hTOPO IIIα alone (middle) or BLM and hTOPO IIIα together (bottom). All reactions contained 150 nM RPA. The positions of supercoiled DNA (form I), relaxed DNA (form II) and intermediate topoisomers are indicated on the right. (B) Quantification of the data from (A), showing loss of form I DNA in the presence of hTOPO IIIα alone (closed cicles) or BLM and hTOPO IIIα together (open circles). (C) Stimulation of hTOPO IIIα by BLM is dependent on RPA. Relaxation of supercoiled φX174 DNA incubated with various combinations of BLM, hTOPO IIIα and RPA, as indicated above the panel. Positions of supercoiled DNA (form I), relaxed DNA (form II) and topoisomers are indicated on the right.

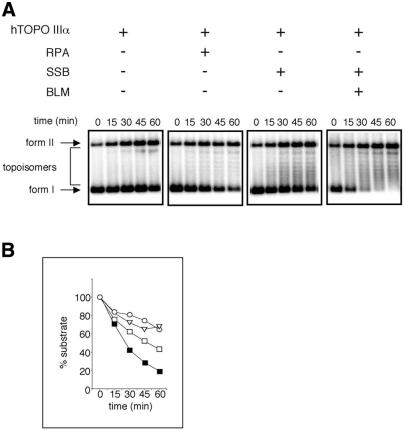

The stimulatory effect of BLM on the activity of hTOPO IIIα was found to be dependent on the presence of RPA in the reactions (Fig. 1C). It was therefore possible that RPA inhibits hTOPO IIIα by binding to ssDNA regions in the negatively supercoiled substrate, thereby preventing access of hTOPO IIIα to the DNA. BLM might then act to stimulate hTOPO IIIα by displacing RPA from the DNA. To eliminate this possibility, we examined the effect of RPA on hTOPO IIIα activity in the absence of BLM. RPA did not inhibit the plasmid relaxation activity of hTOPO IIIα, but rather had a mild stimulatory effect (Fig. 2). This effect appeared to be solely a function of RPA binding to ssDNA, as opposed to a protein–protein interaction occurring between RPA and hTOPO IIIα, since a similar stimulatory effect was also seen when RPA was substituted by E.coli SSB (Fig. 2). We therefore analysed whether SSB could substitute for RPA in supporting the stimulatory effects of BLM on the activity of hTOPO IIIα. Figure 2 shows that in the presence of SSB, BLM still caused a stimulation of hTOPO IIIα plasmid relaxation activity. Due to the apparent functional equivalence of RPA and SSB in these reactions, coupled with the commercial availability of SSB, the bacterial protein was used in all subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

Effects of RPA and SSB on plasmid relaxation catalysed by hTOPO IIIα. (A) Time course showing the relaxation of supercoiled φX174 DNA in the presence of combinations of BLM, hTOPO IIIIα, SSB or RPA, as indicated above the panels. Positions of supercoiled DNA (form I), relaxed DNA (form II) and topoisomers are indicated on the left. (B) Quantification of the loss of form I DNA in the presence of hTOPO IIIα alone (open circles) or of hTOPO IIIα in the presence of RPA (open triangles) or SSB (open squares) or of hTOPO IIIα in the presence of BLM and SSB (closed squares).

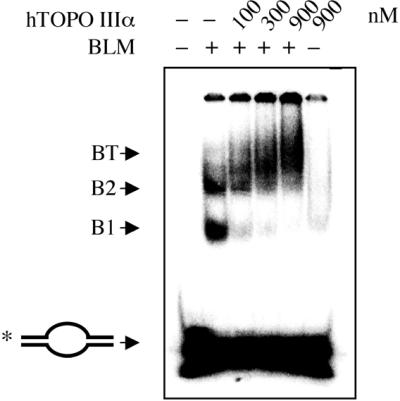

BLM can recruit hTOPO IIIα to single-stranded DNA bubbles

BLM and hTOPO IIIα have been shown to interact directly with each other and form a complex in vivo (34,35). Moreover, it has been shown that the ability of ectopically expressed BLM to reduce the elevated frequency of SCEs in BS cells correlates with its ability to interact with hTOPO IIIα (36). The stimulatory effect of BLM on the activity of hTOPO IIIα that we observed might therefore be mediated by the recruitment of hTOPO IIIα to its site of action by BLM. In such a scenario, BLM should be able to simultaneously interact with both DNA and hTOPO IIIα. We have shown previously that BLM can unwind a duplex DNA molecule that contains a single-stranded bubble of the sort that is a characteristic of negatively supercoiled DNA (6). We tested, therefore, the ability of BLM to bind simultaneously to a synthetic bubble-containing duplex DNA substrate and to hTOPO IIIα. As expected, BLM was found to bind the bubble-containing substrate and generated two retarded complexes designated B1 and B2 (Fig. 3). A proportion of the substrate was also incorporated into a complex that was retained in the wells. Since this material did not resolve under the gel running conditions employed, it was not possible to anaylse further the nature of these apparent aggregates of DNA and protein. Quantification of the amount of DNA in these complexes revealed that B1 and B2 represented 9 and 6%, respectively, of the total substrate in the reaction. In contrast, at the concentrations used in Figure 3, hTOPO IIIα displayed a negligible binding affinity for the DNA substrate. However, the addition of hTOPO IIIα to BLM-containing reactions resulted in the conversion of 93% of B1 and 54% of B2 into a new, slower migrating complex, termed BT (Fig. 3). Since concentrations of hTOPO IIIα were used at which hTOPO IIIα alone maximally bound <5% of the substrate, the conversion of the majority of B1 and B2 into BT indicates that hTOPO IIIα preferentially binds B1 and B2 over the DNA substrate alone. These data also imply that DNA-bound BLM can still form a complex with hTOPO IIIα and are consistent with the notion that BLM recruits hTOPO IIIα to its site of action on DNA.

Figure 3.

BLM can recruit hTOPO IIIα to ssDNA structures. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay using a bubble DNA substrate, 300 nM BLM (where indicated by + above the lanes) and varying concentrations of hTOPO IIIα, as indicated above the lanes. The positions of the unbound DNA bubble substrate (end-labeled on one strand as indicated by the asterisk) and protein–DNA complexes (B1, B2 and BT) are indicated on the left.

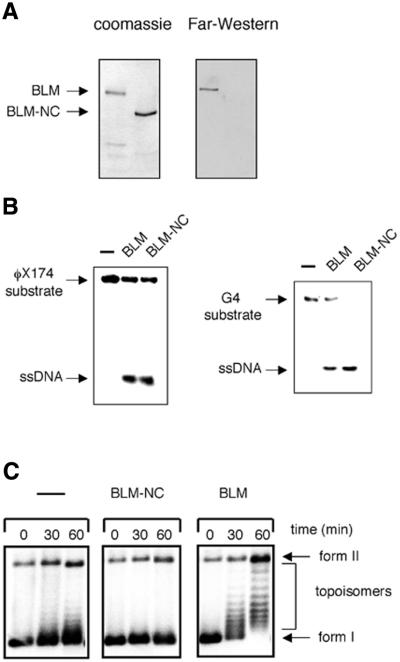

Purification of a hTOPO IIIα binding-defective form of BLM that retains helicase activity

To confirm that the stimulatory effect of BLM on hTOPO IIIα activity requires BLM to recruit hTOPO IIIα to its site of action, a mutant BLM protein was generated that was no longer able to interact with hTOPO IIIα. Mapping studies have revealed that two hTOPO IIIα interaction domains exist in BLM that are located between residues 1–212 and 1267–1417 (35). A hexahistidine-tagged truncated protein, BLM-NC, that consists of residues 213–1266 of BLM and does not, therefore, contain either of the hTOPO IIIα interaction domains, was expressed in yeast and purified to near homogeneity by nickel-chelate affinity chromatography. BLM-NC had an apparent molecular mass of ∼150 kDa on SDS–PAGE (Fig. 4A) and was recognised on western blots by both polyclonal and monoclonal anti-BLM antibodies (35), as well as by an anti-hexahistidine tag antibody (data not shown), thereby confirming its identity.

Figure 4.

A truncated form of BLM that does not bind to hTOPO IIIα fails to stimulate topoisomerase activity. (A) A Coomassie blue stained polyacrylamide gel of purified BLM and BLM-NC (left) and a far-western blot (right) of the same BLM and BLM-NC proteins using hTOPO IIIα as probe (see text for details). (B) Comparison of the helicase activity of the BLM and BLM-NC proteins on substrates comprising an oligonucleotide annealed to single-stranded φX174 DNA (left) and G4 DNA (right). The positions of the substrate and the unwound ssDNA products are indicated on the left of each panel. Lanes marked – contained no BLM protein. (C) Time course comparing the ability of BLM and BLM-NC to stimulate the topoisomerase activity of hTOPO IIIα on supercoiled φX174 DNA. Reactions contained hTOPO IIIα together with no additional protein (left), BLM-NC protein (middle) or full-length BLM protein (right). All reactions contained SSB.

To establish that BLM-NC no longer bound hTOPO IIIα, and hence to eliminate the possibility that additional hTOPO IIIα interaction domains might be present in the BLM protein not detected in our previous studies, far-western analysis using hTOPO IIIα as a probe was performed with BLM and BLM-NC. After separation of the BLM and BLM-NC proteins by SDS–PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose filters, the membranes were incubated with hTOPO IIIα before being washed to remove any unbound material. hTOPO IIIα was then detected by western analysis using a previously characterized polyclonal antibody (D6) (35). We have shown using this technique that hTOPO IIIα associates with full-length BLM (35), and this result was confirmed in the current experiments (Fig. 4A). In contrast, hTOPO IIIα did not bind to BLM-NC (Fig. 4A), confirming that all hTOPO IIIα interaction domains have been removed by truncation of BLM to create BLM-NC.

Despite the fact that relatively large regions of BLM were deleted to generate BLM-NC, the truncated protein was still catalytically active and was able to unwind a variety of DNA substrates that have been shown to be substrates for the full-length protein (4,6,7). These included oligonucleotides annealed to a circular ssDNA and highly stable G4 DNA structures (Fig. 4B).

A hTOPO IIIα binding-defective mutant form of BLM cannot stimulate hTOPO IIIα

We next compared the ability of BLM and BLM-NC to stimulate the activity of hTOPO IIIα. Significantly, the stimulatory effect on hTOPO IIIα activity observed with full-length BLM was not seen when BLM was substituted by BLM-NC (Fig. 4C). This failure of BLM-NC to stimulate hTOPO IIIα was seen over a wide concentration range (81-fold), with higher concentrations even having a mild inhibitory effect on hTOPO IIIα (Fig. 4C). We conclude, therefore, that the stimulatory effect of BLM on hTOPO IIIα requires that the two proteins be capable of forming a complex.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we report the first demonstration of a functional biochemical interaction between a eukaryotic RecQ family DNA helicase and topoisomerase III. BLM was found to significantly stimulate the ability of hTOPO IIIα to act upon negatively supercoiled DNA. When hTOPO IIIα alone was incubated with supercoiled φX174 DNA, two classes of reaction products were observed. These were in the form of topoisomers that appeared after 15 min incubation, and form II DNA that only accumulated after longer periods of incubation, up to 60 min. The latter class of reaction products most likely consisted of fully relaxed DNA, since their appearance occurred only after the formation of topoisomers. However, it is also possible that a proportion of form II molecules contained single strand nicks. Indeed, Wilson-Sali and Hsieh (37) have reported recently that Top3β from D.melanogaster is able to catalyse the nicking of negatively supercoiled DNA. It is presently unknown if hTOPO IIIα possesses an equivalent endonucleolytic activity. However, we are currently addressing this issue and determining what differential effects BLM might have on the topoisomerase versus putative endonuclease activities of hTOPO IIIα.

BLM was found able to bind simultaneously to both hTOPO IIIα and DNA. Moreover, the stimulation of hTOPO IIIα by BLM was lost when BLM was modified to eliminate all of the hTOPO IIIα interaction domains. We therefore propose that one role of BLM is to recruit hTOPO IIIα to its site of action. This proposal is supported by a number of observations. In normal cells, BLM and hTOPO IIIα can be detected together in subnuclear structures termed PML bodies (38–41). However, in BS cells, hTOPO IIIα is expressed normally but is aberrantly localised in the nucleus (34,35). Furthermore, recent studies on Sgs1p, the budding yeast homologue of BLM, which also interacts with Top3p, have shown that expression of mutant forms of Sgs1p that cannot associate withTop3p are unable to complement several aspects of the sgs1 phenotype, including sensitivity to methylmethane sulphonate and hydroxyurea, which damage DNA and inhibit DNA replication, respectively (32). However, this requirement for Sgs1p to interact with Top3p can be circumvented by the expression of a fusion protein consisting of Top3p fused to the N-terminus of a Top3p binding-defective form of Sgs1p (32). Together, these data indicate that the evolutionarily conserved interaction between RecQ helicases and topoisomerase III serves to recruit topoisomerase III to its site of action.

The requirement for the presence of either RPA or SSB in the reactions to observe the stimulatory effect of BLM on the activity of hTOPO IIIα suggests that the DNA structure BLM recruits hTOPO IIIα to has single-stranded character. Consistent with this is the ability of BLM to recruit hTOPO IIIα to single-stranded ‘bubbles’. In human cells, the nature of the DNA structure that BLM loads hTOPO IIIα onto remains to be determined. TOPO IIIα is required for embryonic development in mice (42), indicating that TOPO IIIα performs an essential role that cannot be provided by other topoisomerases. Similarly, in both budding and fission yeast, neither Top1p nor Top2p can functionally substitute for Top3p (26,27,29,30). Taken together, these findings indicate that eukaryotic topoisomerase III enzymes do not function as typical topoisomerases and, consistent with this, it has been reported previously that Top3p is unlikely to play a significant role in regulating the overall supercoiling status of the budding yeast genome (reviewed in 43). Mutants lacking topoisomerase III, as well as those defective in RecQ family helicases, including BLM, generally display hyper-recombination throughout the genome (14–19,26). This would suggest that the BLM–hTOPO IIIα complex acts to suppress inadvertant recombination or to disrupt inappropriately paired DNA molecules. One possible target for the complex is the Holliday junction recombination intermediate. It is known that RecQ, Sgs1p, WRN and BLM can disrupt Holliday junctions (5,6,44–46). Moreover, we have shown recently that BLM promotes the ATP-dependent branch migration of these junctions (5). Through catalysing this reaction, BLM may act to promote and/or eliminate recombinants, depending upon the circumstances. Although the role of topoisomerase III in this process is unclear, it may be significant that yeast Top3p has been shown to be required for the resolution of meiotic recombination intermediates (27). The possibility exists, therefore, that BLM recruits hTOPO IIIα to Holliday junctions to affect their resolution. Ongoing studies of the effects of hTOPO IIIα on BLM-catalysed Holliday junction branch migration reactions aim to address this possibility. A second potential role for the BLM–hTOPO IIIα complex is in the elimination of G-quadruplex DNA in order to permit progression of the replication and/or transcription machinery. This ability of BLM to unwind such non-canonical Watson–Crick DNA structures is a conserved function of the RecQ family helicases (13). G4 DNA has been suggested to be highly recombinogenic due primarily to its potential to lead to replication fork stalling and hence the formation of DNA double-strand breaks.

In summary, we have shown that BLM stimulates the activity of hTOPO IIIα and that this stimulation requires that the two proteins be able to form a stable complex. We propose that BLM functions to regulate the levels of genetic recombination through the recruitment of hTOPO IIIα to recombinogenic DNA structures and/or recombination intermediates. The biochemical functions of BLM and hTOPO IIIα appear to be intimately connected, consistent with the observation that lack of BLM in BS cell lines causes hTOPO IIIα to be mislocalised in the nucleus (34,35). It is therefore quite possible that the diverse phenotypes observed in BS cells are not due solely to a loss of BLM. Instead, ‘uncoupling’ of the BLM–hTOPO IIIα heteromeric helicase/topoisomerase complex might be at least partially responsible for this phenotypic diversity.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs J.-F. Riou and H. Goulaouic for hTOPO IIIα, Dr R. Wood for RPA, Dr C. Norbury for critical reading of the manuscript and members of the Cancer Research UK Genome Integrity Group for useful discussions. This work was supported by Cancer Research UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.German J. (1993) Bloom syndrome: a Mendelian prototype of somatic mutational disease. Medicine, 72, 393–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaganti R.S., Schonberg,S. and German,J. (1974) A manyfold increase in sister chromatid exchanges in Bloom’s syndrome lymphocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 71, 4508–4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis N.A., Groden,J., Ye,T.Z., Straughen,J., Lennon,D.J., Ciocci,S., Proytcheva,M. and German,J. (1995) The Bloom’s syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell, 83, 655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karow J.K., Chakraverty,R.K. and Hickson,I.D. (1997) The Bloom’s syndrome gene product is a 3′-5′ DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 30611–30614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karow J.K., Constantinou,A., Li,J.L., West,S.C. and Hickson,I.D. (2000) The Bloom’s syndrome gene product promotes branch migration of holliday junctions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 6504–6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohaghegh P., Karow,J.K., Brosh,R.M.,Jr, Bohr,V.A. and Hickson,I.D. (2001) The Bloom’s and Werner’s syndrome proteins are DNA structure-specific helicases. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 2843–2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun H., Karow,J.K., Hickson,I.D. and Maizels,N. (1998) The Bloom’s syndrome helicase unwinds G4 DNA. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 27587–27592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Brabant A.J., Ye,T., Sanz,M., German,I.J., Ellis,N.A. and Holloman,W.K. (2000) Binding and melting of D-loops by the Bloom syndrome helicase. Biochemistry, 39, 14617–14625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu C., Oshima,J., Fu,Y., Wijsman,E.M., Hisama,F., Alisch,R., Matthews,S., Nakura,J., Miki,T., Ouais,S. et al. (1996) Positional cloning of the Werner’s syndrome gene. Science, 272, 258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitao S., Shimamoto,A., Goto,M., Miller,R.W., Smithson,W.A., Lindor,N.M. and Furuichi,Y. (1999) Mutations in RECQL4 cause a subset of cases of Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Nature Genet., 22, 82–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohaghegh P. and Hickson,I.D. (2001) DNA helicase deficiencies associated with cancer predisposition and premature ageing disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet., 10, 741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu L., Davies,S.L. and Hickson,I.D. (2000) Roles of RecQ family helicases in the maintenance of genome stability. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol., 65, 573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karow J.K., Wu,L. and Hickson,I.D. (2000) RecQ family helicases: roles in cancer and aging. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 10, 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanada K., Ukita,T., Kohno,Y., Saito,K., Kato,J.-I. and Ikeda,H. (1997) RecQ DNA helicase is a suppressor of illegitimate recombination in Escherichia coli. Genetics, 94, 3860–3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuchi K., Martin,G.M. and Monnat,R.J.,Jr (1989) Mutator phenotype of Werner syndrome is characterized by extensive deletions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 5893–5897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangloff S., McDonald,J.P., Bendixen,C., Arthur,L. and Rothstein,R. (1994) The yeast type I topoisomerase Top3 interacts with Sgs1, a DNA helicase homolog: a potential eukaryotic reverse gyrase. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 8391–8398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart E., Chapman,C.R., Al-Khodairy,F., Carr,A.M. and Enoch,T. (1997) rqh1+, a fission yeast gene related to the Bloom’s and Werner’s syndrome genes, is required for reversible S phase arrest. EMBO J., 16, 2682–2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watt P.M., Hickson,I.D., Borts,R.H. and Louis,E.J. (1996) SGS1, a homologue of the Bloom’s and Werner’s syndrome genes, is required for maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 144, 935–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayama H., Nakayama,K., Nakayama,R., Irino,N., Nakayama,Y. and Hanawalt,P.C. (1984) Isolation and genetic characterization of a thymineless death-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K12: identification of a new mutation (recQ1) that blocks the RecF recombination pathway. Mol. Gen. Genet., 195, 474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu L. and Hickson,I.D. (2001) RecQ helicases and topoisomerases: components of a conserved complex for the regulation of genetic recombination. Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 58, 894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Champoux J.J. (2001) DNA topoisomerases: structure, function and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 70, 369–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanai R., Caron,P.R. and Wang,J.C. (1996) Human TOP3: a single-copy gene encoding DNA topoisomerase III. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 3653–3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seki T., Seki,M., Onodera,R., Katada,T. and Enomoto,T. (1998) Cloning of cDNA encoding a novel mouse DNA topoisomerase III (Topo IIIbeta) possessing negatively supercoiled DNA relaxing activity, whose message is highly expressed in the testis. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 28553–28556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goulaouic H., Roulon,T., Flamand,O., Grondard,L., Lavelle,F. and Riou,J.F. (1999) Purification and characterization of human DNA topoisomerase IIIα. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2443–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson T.M., Chen,A.D. and Hsieh,T. (2000) Cloning and characterization of Drosophila topoisomerase IIIbeta. Relaxation of hypernegatively supercoiled DNA. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 1533–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallis J.W., Chrebet,G., Brodsky,G., Rolfe,M. and Rothstein,R. (1989) A hyper-recombination mutation in S. cerevisiae identifies a novel eukaryotic topoisomerase. Cell, 58, 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gangloff S., de Massy,B., Arthur,L., Rothstein,R. and Fabre,F. (1999) The essential role of yeast topoisomerase III in meiosis depends on recombination. EMBO J., 18, 1701–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakraverty R.K., Kearsey,J.M., Oakley,T.J., Grenon,M., de La Torre Ruiz,M.A., Lowndes,N.F. and Hickson,I.D. (2001) Topoisomerase III acts upstream of Rad53p in the S-phase DNA damage checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 7150–7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maftahi M., Han,C.S., Langston,L.D., Hope,J.C., Zigouras,N. and Freyer,G.A. (1999) The top3(+) gene is essential in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and the lethality associated with its loss is caused by Rad12 helicase activity. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 4715–4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodwin A., Wang,S.W., Toda,T., Norbury,C. and Hickson,I.D. (1999) Topoisomerase III is essential for accurate nuclear division in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 4050–4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harmon F.G., DiGate,R.J. and Kowalczykowski,S.C. (1999) RecQ helicase and topoisomerase III comprise a novel DNA strand passage function: a conserved mechanism for control of DNA recombination. Mol. Cell, 3, 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett R.J. and Wang,J.C. (2001) Association of yeast DNA topoisomerase III and Sgs1 DNA helicase: studies of fusion proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 11108–11113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fricke W.M., Kaliraman,V. and Brill,S.J. (2001) Mapping the DNA topoisomerase III binding domain of the Sgs1 DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 8848–8855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson F.B., Lombard,D.B., Neff,N.F., Mastrangelo,M.A., Dewolf,W., Ellis,N.A., Marciniak,R.A., Yin,Y., Jaenisch,R. and Guarente,L. (2000) Association of the Bloom syndrome protein with topoisomerase IIIalpha in somatic and meiotic cells. Cancer Res., 60, 1162–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu L., Davies,S.L., North,P.S., Goulaouic,H., Riou,J.F., Turley,H., Gatter,K.C. and Hickson,I.D. (2000) The Bloom’s syndrome gene product interacts with topoisomerase III. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 9636–9644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu P., Beresten,S.F., van Brabant,A.J., Ye,T.Z., Pandolfi,P.P., Johnson,F.B., Guarente,L. and Ellis,N.A. (2001) Evidence for BLM and Topoisomerase IIIalpha interaction in genomic stability. Hum. Mol. Genet., 10, 1287–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson-Sali T. and Hsieh,T.S. (2002) Generation of double-stranded breaks in hypernegatively supercoiled DNA by Drosophila topoisomerase III beta, a type IA enzyme. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 26865–26871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong S., Hu,P., Ye,T.Z., Stan,R., Ellis,N.A. and Pandolfi,P.P. (1999) A role for PML and the nuclear body in genomic stability. Oncogene, 18, 7941–7947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanz M.M., Proytcheva,M., Ellis,N.A., Holloman,W.K. and German,J. (2000) BLM, the Bloom’s syndrome protein, varies during the cell cycle in its amount, distribution and co-localization with other nuclear proteins. Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 91, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bischof O., Kim,S.H., Irving,J., Beresten,S., Ellis,N.A. and Campisi,J. (2001) Regulation and localization of the Bloom syndrome protein in response to DNA damage. J. Cell Biol., 153, 367–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishov A.M., Sotnikov,A.G., Negorev,D., Vladimirova,O.V., Neff,N., Kamitani,T., Yeh,E.T., Strauss,J.F.,III and Maul,G.G. (1999) PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol., 147, 221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li W. and Wang,J.C. (1998) Mammalian DNA topoisomerase IIIalpha is essential in early embryogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 1010–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J.C. (1996) DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 65, 635–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bennett R.J., Keck,J.L. and Wang,J.C. (1999) Binding specificity determines polarity of DNA unwinding by the Sgs1 protein of S. cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol., 289, 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Constantinou A., Tarsounas,M., Karow,J.K., Brosh,R.M., Bohr,V.A., Hickson,I.D. and West,S.C. (2000) Werner’s syndrome protein (WRN) migrates Holliday junctions and co-localises with RPA upon replication arrest. EMBO Rep., 1, 80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harmon F.G. and Kowalczykowski,S.C. (1998) RecQ helicase, in concert with RecA and SSB proteins, initiates and disrupts DNA recombination. Genes Dev., 12, 1134–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]