Abstract

The Arabidopsis SUPERMAN (SUP) gene has been shown to be important in maintaining the boundary between stamens and carpels, and is presumed to act by regulating cell proliferation. In this work, we show that the SUP protein, which contains a single Cys2–His2 zinc finger domain including the QALGGH sequence, highly conserved in the plant zinc finger proteins, binds DNA. Using a series of deletion mutants, it was determined that the minimal domain required for specific DNA binding (residues 15–78) includes the single zinc finger and two basic regions located on either side of this motif. Furthermore, amino acid substitutions in the zinc finger or in the basic regions, including a mutation that knocks out the function of the SUP protein in vivo (glycine 63 to aspartate), have been found to abolish the activity of the SUP DNA-binding domain. These results strongly suggest that the SUP protein functions in vivo by acting as a DNA-binding protein, likely involved in transcriptional regulation. The association of both an N-terminal and a C-terminal basic region with a single Cys2–His2 zinc finger represents a novel DNA-binding motif suggesting that the mechanism of DNA recognition adopted by the SUP protein is different from that described so far in other zinc finger proteins.

INTRODUCTION

Proteins containing classical type (or Cys2–His2) zinc finger domains represent the largest group of eukaryotic DNA-binding proteins known to date (1). The classical zinc finger domain, originally described in the Xenopus laevis transcription factor IIIA (TFIIIA) (2), contains the amino acid sequence (F/Y)XCX2–5CX3(F/Y)X5ΨX2HX3–5H, where X represents any amino acid and Ψ is a hydrophobic residue; the two cysteines and the two histidines tetrahedrally coordinate a zinc ion to form a compact structure containing a β-hairpin and an α-helix (ββα) (1,3,4). Structural studies conducted on classical zinc finger–DNA complexes have revealed that sequence-specific recognition is achieved by contacts between the α-helix of the zinc finger and bases in the major groove of the DNA. The key residues of the helix involved in base-specific DNA contacts are located at positions 6, 3, 2 and –1 (numbered relative to the N-terminus of the helix) (1,5–8).

The number of zinc finger domains present in proteins varies from 1 to 37, and a single zinc finger domain in itself is not sufficient for high-affinity binding to a specific DNA target sequence. In fact, proteins containing multiple zinc finger domains require a minimum of two zinc fingers for high-affinity DNA binding (1). Recently, it has been demonstrated that the single zinc finger domain present in the Drosophila GAGA transcription factor is capable of sequence-specific DNA binding; this single zinc finger domain is flanked at its N-terminus by basic residues which stabilize DNA binding, providing further contacts with both the major and minor groove of the DNA (8,9).

Many proteins containing Cys2–His2 zinc finger domains have recently been identified in plants and several data suggest that these proteins are involved in important biological processes (10,11). A structural feature common to the plant TFIIIA-type zinc finger proteins, which distinguishes them from their counterparts in other eukaryotes, is the high conservation of a unique amino acid sequence (QALGGH) present in their zinc finger domains. This sequence is present in most of the plant zinc finger proteins identified so far, and is localized in the α-helical region within the putative DNA-contacting surface of the zinc finger (10,11). In Petunia, more than 30 zinc finger proteins have been identified that contain the highly conserved QALGGH sequence. These proteins are known as the EPF family (10), named after its first identified member, EPF1(12). The Petunia EPF proteins contain multiple zinc finger domains with a linker of variable length between the domains, which is longer than that normally observed in other eukaryotic zinc finger proteins (typically seven amino acids). Interaction with the target DNA sequence has been best characterized for two members of this family, ZPT2-1 and ZPT2-2 (renamed from EPF1 and EPF2-5, respectively). These proteins bind to two separate AGT sequences, the distance between the zinc finger domains seeming to dictate the recognition of the spacing between the DNA target sequences (13–16). Mutagenesis experiments have also demonstrated that the conserved QALGGH sequence is critical for DNA-binding activity of these proteins and that at least two zinc finger domains are necessary for this interaction (14,15).

Among classical zinc finger proteins in plants, the SUPERMAN (SUP) protein of Arabidopsis is the best characterized in terms of its genetic function. Mutations causing extra stamens to form at the expense of normal carpel development have in fact been mapped in the SUP gene (17). Though genetic data clearly indicate that the SUP gene plays an important role in normal flower development, it is not yet fully understood how the protein functions. The open reading frame of the SUP gene encodes a protein of 204 amino acids which contains a single zinc finger domain with the highly conserved QALGGH sequence. The C-terminal of the SUP zinc finger is a region rich in serine and proline, followed by a cluster of basic residues and a region shown to act as a transcriptional repression domain (17,18). All of the protein motifs suggested that SUP may act as a transcription factor, but currently there are no reports of it binding specifically to a target DNA sequence.

In this paper, we present a study of the DNA-binding activity of the SUP protein. We demonstrate that the single zinc finger domain present in this protein is able to specifically bind DNA. Just as with the GAGA factor, DNA binding of the SUP single zinc finger domain is stabilized by flanking residues. In the case of the SUP zinc finger motif the binding requires the presence of two basic regions located on either side of the zinc finger. These results support the idea that the SUP protein is a transcription factor with its own DNA-binding ability, which plays an important role in the control of flower development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and purification of the proteins

DNA fragments encoding the different segments of the SUP protein were generated by PCR from the SUP cDNA. Oligonucleotides were synthesized on the basis of the published sequence (17). The following oligonucleotides were used as primers: primer 1, 5′-CGGGATCCATGGAGAGATCAAACAGCATAGAGTTGAGGAACAGCTTCTATGGCCGTGCAAGAACTTC-3′, and primer 2, 5′-CGGGAT CCTTAAGCGAAACCCAAACGGAGTTCTAGATC-3′, for SUP1–204; primer 1, and primer 3, 5′-CGGGATCCTCATAATCTGAGTCTTGCTCTGTCTCTTCTG-3′, for SUP1–78; primer 4, 5′-CGGGATCCGGCCGTGCAAGAACTTCACC-3′, and primer 3 for SUP15–78; primer 5, 5′-CGGGATCCTCACCATGGAGCTATGGAGATTATG-3′, and primer 3 for SUP20–78; primer 4 and primer 6, 5′-CGGGATCCTCAGTCTCTTCTGTGAACATTCATG-3′, for SUP15–72. The point mutants were generated by PCR-mediated mutagenesis (19) using primers mut1, 5′-CGGGATCCGGCGCTGCAGCAACTTCACCATGGAGCTATG-3′, and primer 3 for SUP15–78mut1; primer 4 and primer mut2, 5′-CGGGATCCTTATAATGCGAGTGCTGCTGCGTCTCTTCTGTGAACATTC-3′, for SUP15–78mut2; primer mut3, 5′-CGGGATCCGGCCGTGCAAGAACTTCACCATGGAGCTATGGAGATTATGATAATTCCCAACAGGATCATGATTA-3′, and primer 3 for C30S, and primer 4 and primer mut4, 5′-CGGGATCCTCATAATCTGAGTCTTGCTCTGTCTCTTCTGTGAACATTCATGTGGCCATCAAGTGCTTGAGCCGATC-3′, for G63D. All the PCR products coding for the different proteins were subcloned into the BamHI site of the bacterial expression vector pGEX4T3 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). All plasmids obtained were sequenced to confirm that there were no mutations in the coding sequences.

The fusion proteins were overexpressed in BL21, induced for 3 h in the presence of 1 mM IPTG at 37°C, sonicated in 1× PBS (20) pH 7.4, 1 mM PMSF, 1 µM leupeptin, 1 µM aprotinin, 1 µM pepstatin and 10 µg lysozyme/ml bacterial culture, adjusted to 1% Triton X-100, centrifuged and the supernatant bound to a glutathione–Sepharose column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s advice. Following washes with 1× PBS, purified fractions were eluted in the presence of 10 mM glutathione, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl and used for band-shift assays.

Gel-mobility-shift analysis

Unless otherwise specified, 200 ng of the purified proteins were incubated for 10 min on ice with 50 fmol of the labeled duplex oligonucleotide Ep1ss (5′-AGG TTT GAC AGT GTC ACT TT-3′) or mutEp1ss (5′-AGG TTT GAC GAC GTC ACT TT-3′) in the presence of 25 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 6.25 mM MgCl2, 0.2% NP-40, 5% glycerol and 500 ng of double-stranded poly(dI/dC–dI/dC) (Roche). After incubation, the mixture was loaded on a 5% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide/bisacrylamide, 29:1) and run in 0.5× TBE (20) at 4°C (200 V for 2 h). As a non-specific competitor for competition experiments the oligonucleotide NS (5′-AAA ACCCGAGGGTACGAACG-3′) was used.

RESULTS

To determine if the SUP protein was able to bind DNA, a fragment encoding the entire protein was cloned into the pGEX-4T3 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) expression vector. The protein (SUP1–204) was expressed in Escherichia coli as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion and purified. A gel-mobility-shift analysis was performed on the purified protein to determine its ability to bind DNA (Fig. 1). The proteins with zinc finger domains most closely related to that of SUP are the EPF proteins from Petunia, which bind DNA via multiple zinc finger domains containing the QALGGH motif (10,11). From the conserved amino acid sequences in the DNA recognition region of the zinc finger motifs, we reasoned that SUP might bind a similar DNA sequence. Thus, we used as a probe the oligonucleotide EP1ss which is derived from the sequence recognized by at least three members of the Petunia EPF protein family (13). As shown in Figure 1 (lane 3), the SUP1–204 protein interacts with the EP1ss oligonucleotide to produce a single complex; as expected, the GST protein alone does not bind DNA (Fig. 1, lane 2). A deletion mutant of the SUP1–204 protein, SUP1–78, including the zinc finger domain (residues 1–78, for the sequence see Fig. 2) binds the DNA just as well as the full-length protein (see Fig. 3A, lane 1), indicating that the C-terminal part of the protein is not involved in DNA binding. Interestingly, this C-terminal region has been shown to include a transcriptional repression domain (residues 175–204) (18). The binding specificity of the purified SUP1–78 protein was demonstrated by competition experiments with unlabeled oligonucleotides; the complex is competed by the addition of a 200-fold excess of unlabeled EP1ss oligonucleotide (Fig. 3A, lane 2), but not by the same amount of an unrelated oligonucleotide sequence (NS, Fig. 3A, lane 3). The addition of 50 mM EDTA to the binding reaction (Fig. 3A, lane 4) abolishes the DNA-binding activity, suggesting that the binding of the protein to DNA is zinc dependent.

Figure 1.

Gel-mobility-shift analysis of the SUPERMAN protein. The purified GST (lane 2) and SUP1-204 proteins (lane 3) were incubated with the labeled 20 bp oligonucleotide EP1ss in the presence of binding buffer and subjected to gel-shift analysis (see Materials and Methods).

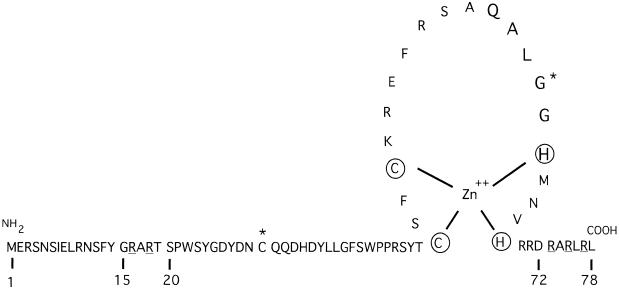

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the SUPERMAN protein (residues 1–78). The terminal residues of the SUP deletion mutants utilized in this study are numbered with reference to the full-length protein. All fragments of the SUP protein, as well as the full-length protein, have been expressed as GST fusions; the QALGGH motif is in large letters; the basic residues which have been mutated in SUP15–78mut1 and SUP15–78mut2 are underlined; residues cysteine 30 and glycine 63, which have been mutated respectively in the G63D an C30S mutants, are indicated by asterisks.

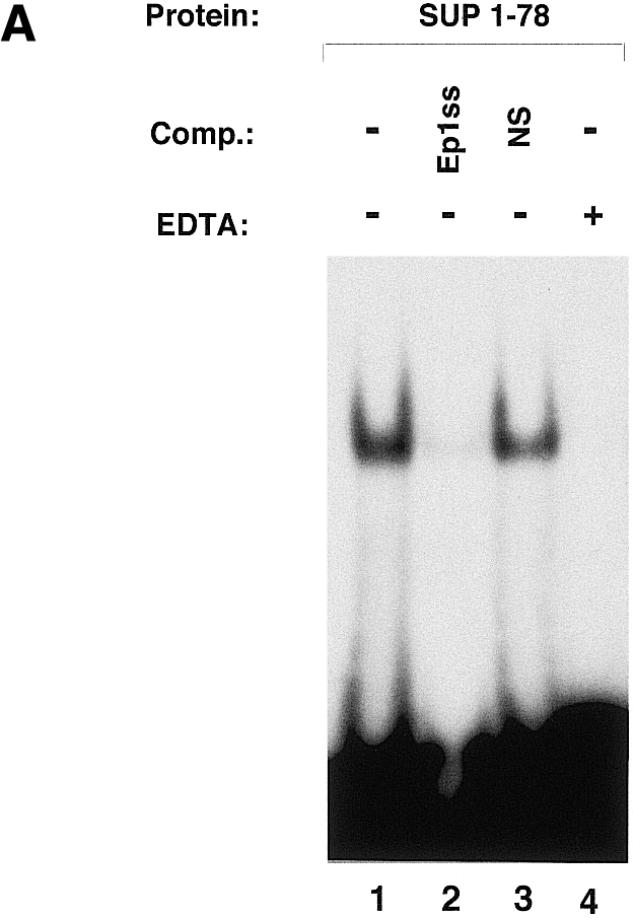

Figure 3.

Gel-mobility-shift analysis of SUP1–78. The DNA-binding specificity and the zinc ion requirement for DNA binding of the SUP1–78 protein has been investigated. (A) Forty nanograms of SUP1–78 were incubated for 10 min on ice in binding buffer in the absence (lane 1) or presence of 10 pmol of unlabeled EP1ss oligonucleotide (lane 2), 10 pmol of an unlabeled oligonucleotide with an unrelated sequence (oligo NS) (lane 3) or 50 mM EDTA (lane 4), then subjected to standard gel-shift analysis using 50 fmol of labeled EP1ss oligonucleotide as a probe. Comp., competitor. (B) The purified SUP1–78 was incubated with the labeled Ep1ss and mutEp1ss labeled oligonucleotides and subjected to gel-shift analysis (see Materials and Methods). The sequences of the oligonucleotides used as probes are indicated. The AGT core sequence of the EP1ss oligonucleotide, which has been mutated to GAC in mutEP1ss, is underlined.

The AGT core sequence of the EP1ss oligonucleotide has been shown to be essential for the recognition of the DNA target site by Petunia EPF protein family members (14). To test if SUPERMAN had a similar DNA-binding specificity, we mutated the EP1ss oligonucleotide by changing the AGT sequence with GAC (mutEP1ss) and tested the mutated oligonucleotide as a probe in a gel-shift experiment with the SUP1–78 protein. As demonstrated by the experiment shown in Figure 3B, substitution of the core AGT sequence drastically reduced the binding of SUP1–78 to the Ep1ss oligonucleotide (compare lane 2 with lane 1 in Fig. 3B), indicating that this core sequence is important for the recognition of the EP1ss oligonucleotide also by the SUPERMAN protein.

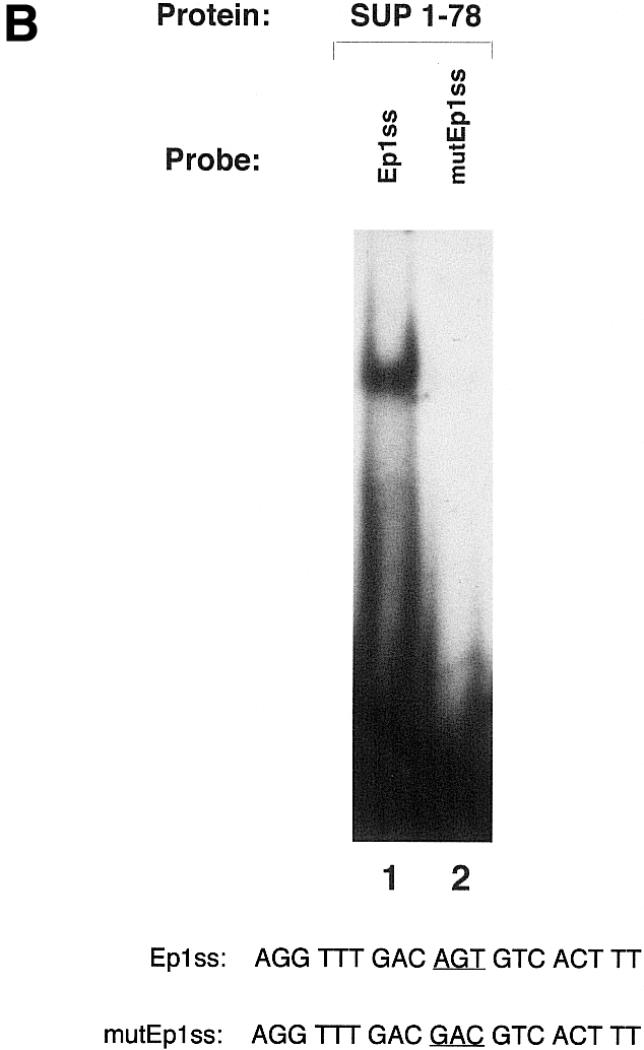

To determine the role of the amino acids flanking the SUP zinc finger domain in stabilizing the interaction with DNA, we prepared a series of deletion mutants of the SUP1–78 protein. Removal of the first 14 N-terminal residues of the SUP protein from SUP1–78 (SUP15–78) did not have any effect on the DNA-binding activity (in Fig. 4 compare SUP15–78, lane 3, with SUP1–78, lane 2), implying that these residues are not involved in the interaction with DNA. Further N-terminal deletion resulted in a protein (SUP20–78) with a drastically reduced DNA-binding activity (Fig. 4, lanes 6 and 7). These results indicate that residues 15–19 of the SUP protein are important in stabilizing the DNA interaction.

Figure 4.

Gel-mobility-shift analysis of SUP1–78 deletion mutants. The purified proteins were incubated with the labeled 20 bp oligonucleotide EP1ss in the presence of binding buffer and subjected to gel-shift analysis (see Materials and Methods). Where indicated (lanes 5 and 7), an estimated 4-fold excess of the purified proteins was used.

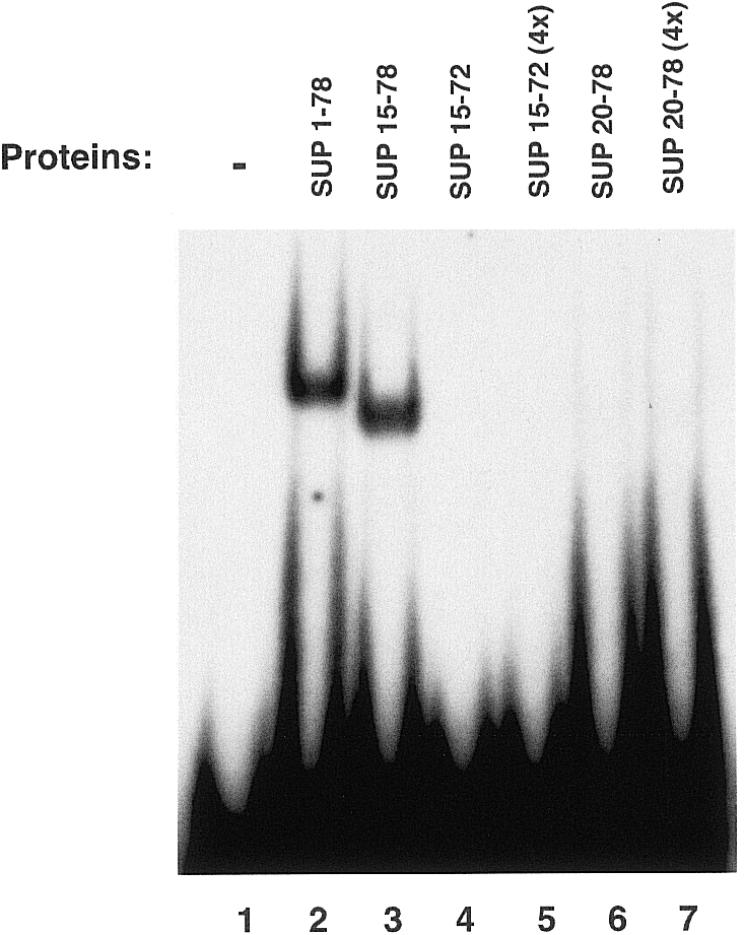

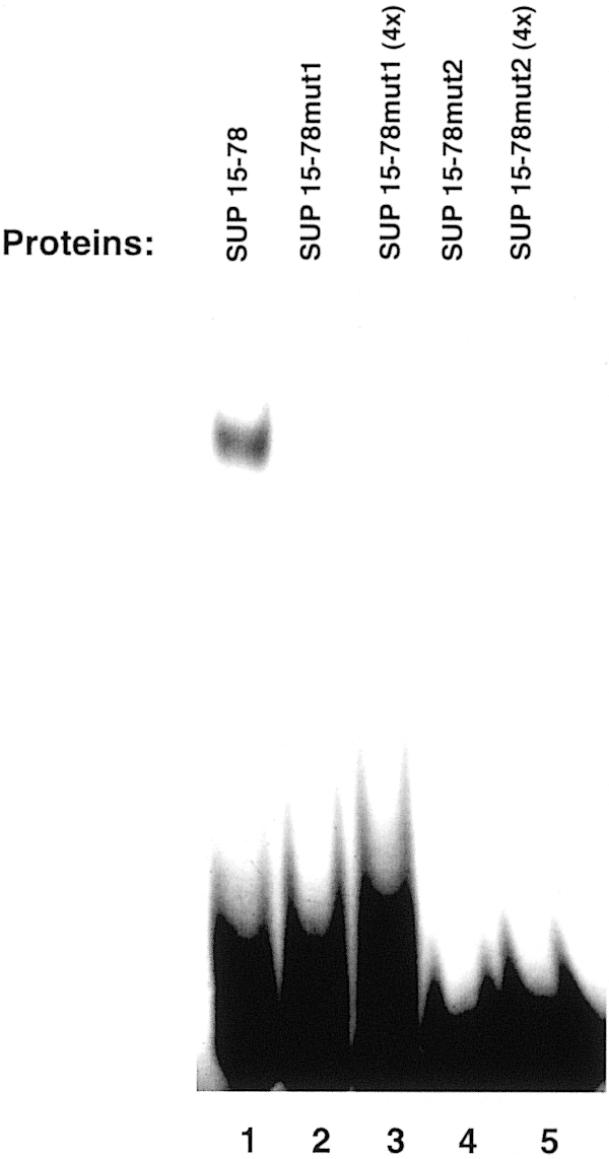

To test if the amino acids located at the C-terminus of the finger domain also play a role in stabilizing the interaction, we deleted from SUP15–78 six residues which flanked the zinc finger domain at its C-terminus. This deletion resulted in a protein (SUP15–72) that failed to display specific DNA binding (Fig. 4, lanes 4 and 5). These results indicate that the stretch of amino acids which are located at the C-terminal of the zinc finger domain also contribute in stabilizing the interaction with the target sequence. Interestingly, the regions deleted in SUP20–78 and in SUP15–72 both contain basic amino acids, which have been shown to be important in stabilizing the DNA binding of other zinc finger domains such as the ones present in the GAGA, GATA-1, GATA-2 and GATA-3 proteins (9,21,22). In order to test if these basic amino acid residues were important for the DNA binding observed with SUP15–78, two mutant proteins (SUP15– 78mut1 and SUP15–78mut2) were prepared and tested for DNA-binding activity. In both mutant proteins, alanine residues were substituted in place of wild-type arginine residues. In SUP15–78mut1, the substitutions were R16A and R18A, while in SUP15–78mut2 the substitutions were R73A, R75A and R77A. As shown in Figure 5, neither mutant proteins displayed DNA-binding activity, even when tested at 4-fold higher concentrations than the wild-type SUP15–78. Taken together, these results imply that basic residues flanking either side of the zinc finger domain of the SUP protein are important in stabilizing the DNA-binding interaction.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the role of the basic amino acids flanking the zinc finger domain in stabilizing DNA binding. The purified proteins were incubated with the labeled 20 bp oligonucleotide EP1ss in the presence of binding buffer and subjected to gel-shift analysis (see Materials and Methods). Where indicated (lanes 3 and 5), an estimated 4-fold excess of the purified proteins was used.

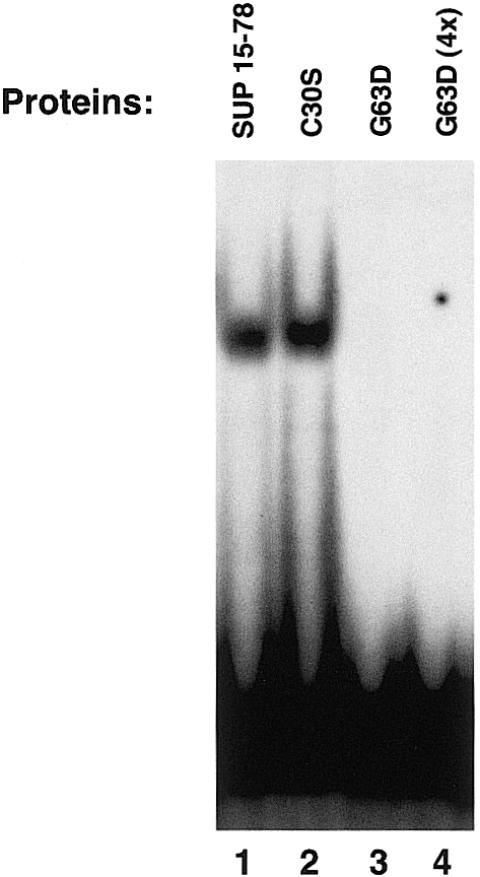

A sup mutant allele (sup3) has been sequenced (17) which contains a point mutation inside the zinc finger domain in which the first glycine of the QALGGH sequence has been mutated to an aspartate residue. Considering that the phenotype of sup3 is the same as that caused by nonsense mutations which completely disrupt the coding sequence, it has been concluded that this glycine residue must be essential for SUP function. This same mutation was introduced in SUP15–78 (G63D mutant) to determine whether it affected its DNA-binding activity. As a control, we produced another point mutant (C30S) in which we changed an amino acid outside of the zinc finger domain (cysteine 30 to serine). As shown in Figure 6, while the C30S protein binds the EP1ss sequence just as the wild-type protein, the G63D mutant failed to display DNA binding under the same binding conditions, even when used in a 4-fold excess. This experiment further confirms the involvement of the zinc finger domain in the recognition of the DNA and demonstrates that the glycine to aspartate mutation that causes a loss of function of the SUP protein interferes with its ability to bind DNA.

Figure 6.

Gel-mobility-shift analysis of the C30S and G63D mutant proteins. The purified proteins were incubated with the labeled 20 bp oligonucleotide EP1ss in the presence of binding buffer and subjected to gel-shift analysis (see Materials and Methods). Where indicated (lane 4) an estimated 4-fold excess of the purified G63D protein was used.

DISCUSSION

The Arabidopsis SUP gene has been shown to be important in maintaining the boundary between stamens and carpels, and is presumed to act by regulating cell proliferation (17,18,23–25). In this work we have shown that the protein encoded by the Arabidopsis SUP gene contains a unique DNA-binding domain which consists of a Cys2–His2 zinc finger domain and two flanking basic regions. These data indicate that the protein likely performs its function in vivo by acting as a sequence-specific DNA-binding factor. In agreement with this hypothesis, when we introduce a point mutation in the SUP DNA-binding domain that has been shown to knock-out the function of the entire protein in vivo (glycine 63 to aspartate), it looses its DNA-binding ability. Considering the recent finding that the C-terminal sequence of the SUP protein (residues 175–204), when fused to a heterologous DNA-binding domain, acts as a transcriptional repression domain (18), the SUP protein is likely to function by binding the DNA and inhibiting the transcription. Further experiments are required to determine the regulatory sequences recognized by the SUP protein in vivo and to identify the genes that are directly controlled by this putative transcription factor.

To date, most of the Cys2–His2-type zinc finger proteins isolated from plants contain the QALGGH motif (11), suggesting that proteins including this motif form a major class of transcription factors in plants. DNA-binding studies conducted on proteins containing multiple zinc finger domains from Petunia reveal that at least two QALGGH zinc finger domains are necessary for high-affinity DNA binding in this class of proteins (14,15). This is consistent with the idea that the number of intermolecular contacts, and hence the strength of the interaction between each classical zinc finger domain and DNA, is not sufficient in its own right to yield high-affinity DNA binding. Interestingly, in the case of the SUP single zinc finger domain the additional contacts required for sequence-specific binding are provided by the two N-terminal and C-terminal extensions comprising two basic regions.

SUP is a member of a protein family in Arabidopsis which contains a single classical zinc finger domain with the conserved QALGGH sequence; to date at least nine members of this family have been characterized (26). The primary structures of both the zinc finger motif and the basic tail at the C-terminus of the α-helix (residues 45–78 in SUP) are very similar in these proteins. However, there is little or no homology in the rest of the protein. It will be interesting to test if all the members of this family are DNA-binding proteins and which structural motifs they use to stabilize the interaction of the finger with the DNA.

It has previously been demonstrated that the single zinc finger of the GAGA protein requires two stretches of basic residues (BR1 and BR2) located at its N-terminus for specific DNA binding (9). The structure of the complex between the DNA-binding domain of the GAGA factor and the oligonucleotide containing its G1A2G3A4G5 consensus binding site (8) revealed details of the interaction. Recognition of G1A2G3 by the zinc finger helix involves residues at position +6, +3 and +2 numbered relative to the N-terminus of the helix. The BR2 forms a short helix that interacts in the major groove, recognizing the G5 of the consensus, while BR1 wraps around the DNA in the minor groove and recognizes the A4 of the target sequence. Many features of the SUP DNA-binding domain indicate that this protein interacts differently with the DNA with respect to the GAGA factor. First, the residues which stabilize the interaction of the SUP finger with the DNA are located on both sides of the zinc finger domain, instead of only at its N-terminus. In this regard, the SUP zinc finger domain resembles the N-terminal zinc finger domains of the GATA-2 and GATA-3 proteins, whose binding to the DNA requires the presence of two basic regions located on either side of the zinc finger domain (22). The major difference with GATA-2 and GATA-3 is that in these proteins chelation of zinc is by four cysteines rather than by two cysteines and two histidines. Within the highly conserved QALGGH sequence present in the SUP zinc finger domain, the underlined glutamine, alanine and glycine residues occupy, respectively, the +2, +3 and +6 positions of the α-helical region, as confirmed by the NMR solution structure of the motif (manuscript in preparation). These amino acids correspond to the residues of the GAGA zinc finger domain that make base-specific contacts with G1A2G3 positions in the target DNA. While it has been reported in other zinc finger proteins that glutamine and alanine are able to recognize specific DNA bases in the context of a DNA-binding site (27–30), the second glycine at position +6, lacking a side chain, is unlikely to make specific contacts with bases of the DNA, suggesting that the SUP protein might use residues present in different positions to recognize the DNA. The results presented in this work suggest that the mechanism of DNA recognition adopted by the SUP protein differs from that described so far for other zinc finger proteins and confirm that the Cys2–His2 motif can be used in a wide variety of structural combinations for DNA recognition. These observations further strengthen the hypothesis that all proteins containing only one classical zinc finger motif have to be considered as potential transcription factors with their own DNA-binding ability. Structural characterization of the SUP zinc finger domain complexed with DNA will be important in defining the mechanism of the interaction and in determining the amino acids involved in nucleic acid recognition.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The SUP cDNA clone was kindly provided by Dr Hajime Sakay and Dr Elliot M. Meyerowitz. We are grateful to Marco Mammucari and Maurizio Muselli for excellent technical assistance. We thank Professor Margherita Sacco for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussion. This work was partly supported by Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca scientifica e tecnologica, grant PRIN 1998 to B.D.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klug A. and Schwabe,J.W.R. (1995) Protein motifs 5. Zinc finger. FASEB J., 9, 597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller J., McLachlan,A.D. and Klug,A. (1985) Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 4, 1609–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe S.A., Nekludova,L. and Pabo,C.O. (2000) DNA recognition by Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 29, 183–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laity J.H., Lee,B.M. and Wright,P.E. (2001) Zinc finger proteins: new insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 11, 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavletich N.P. and Pabo,C.O. (1991) Zinc finger-DNA recognition: crystal structure of a Zif268-DNA complex at 2.1 A. Science, 252, 809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pavletich N.P. and Pabo,C.O. (1993) Crystal structure of a five-finger GLI–DNA complex: new perspectives on zinc fingers. Science, 261, 1701–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairall L., Schwabe,J.W.R., Chapman,L., Finch,J.T. and Rhodes,D. (1993) The crystal structure of a two zinc-finger peptide reveals an extension to the rules for zinc-finger/DNA recognition. Nature, 366, 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omichinski J.G., Pedone,P.V., Felsenfeld,G., Gronenborn,A.M. and Clore,G.M. (1997) The solution structure of a specific GAGA factor–DNA complex reveals a modular binding mode. Nature Struct. Biol., 4, 122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedone P.V., Ghirlando,R., Clore,G.M., Gronenborn,A.M., Felsenfeld,G. and Omichinski,J.G. (1996) The single Cys2–His2 zinc finger domain of the GAGA protein flanked by basic residues is sufficient for high affinity specific DNA binding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 2822–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takatsuji H. (1998) Zinc-finger transcription factors in plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 54, 582–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takatsuji H. (1999) Zinc-finger proteins: the classical zinc finger emerges in contemporary plant science. Plant Mol. Biol., 39, 1073–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takatsuji H., Mori,M., Benfey,P., Ren,L. and Chua,N.-H. (1992) Characterization of a zinc finger DNA-binding protein expressed specifically in Petunia petals and seedlings. EMBO J., 11, 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takatsuji H. Nakamura,N. and Katsumoto,Y. (1994) A new family of zinc finger proteins in petunia: structure, DNA sequence recognition and floral organ-specific expression. Plant Cell, 6, 947–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takatsuji H. and Matsumoto,T. (1996) Target-sequence recognition by separate-type Cys2/His2 zinc finger proteins in plants. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 23368–23373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubo K., Sakamoto,A., Kobayashi,A., Rybka,Z., Kanno,Y., Nakagawa,H., Nishino,T. and Takatsuji,H. (1998) Cys2/His2 zinc-finger protein family of Petunia: evolution and general mechanism of target-sequence recognition. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 608–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshioka K., Fukushima,S., Yamazaki,T., Yoshida,M. and Takatsuji,H. (2001) The plant zinc finger protein ZPT2-2 has unique mode of DNA interaction. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 35802–35807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai H., Medrano,L.J. and Meyerowitz,E.M. (1995). Role of SUPERMAN in maintaining Arabidopsis floral whorl boundaries. Nature, 378, 199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiratsu K., Ohta,M., Matsui,K. and Ohme-Takagi,M. (2002) The SUPERMAN protein is an active repressor whose carboxy-terminal repression domain is required for the development of normal flowers. FEBS Lett., 14, 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White B.A. (1993) Methods in Molecular Biology. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, Vol. 15.

- 20.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 21.Omichinski J.G., Trainor,C., Evans,T., Gronenborn,A.M., Clore,G.M. and Felsenfeld,G. (1993) A small single-“finger” peptide from the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 binds specifically to DNA as a zinc or iron complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 1676–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedone P.V., Omichinski,J.G., Nony,P., Trainor,C., Gronenborn,A.M., Clore,G.M. and Felsenfeld,G. (1997) The N-terminal fingers of chicken GATA-2 and GATA-3 are independent sequence-specific DNA binding domains. EMBO J., 16, 2874–2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandi A.K., Kushalappa,K., Prasad,K. and Vijayraghavan,U. (2000) A conserved function for Arabidopsis SUPERMAN in regulating floral-whorl cell proliferation in rice, a monocotyledonous plant. Curr. Biol., 10, 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kater M.M., Franken,J., van Aelst,A. and Angenent,G.C. (2000) Suppression of cell expansion by ectopic expression of the Arabidopsis SUPERMAN gene in transgenic petunia and tobacco. Plant J., 23, 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakai H., Krizek,B.A., Jacobsen,S.E. and Meyerowitz,E.M. (2000) Regulation of SUP expression identifies multiple regulators involved in Arabidopsis floral meristem development. Plant Cell, 12, 1607–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tague B.W. and Goodman,H.M. (1995) Characterization of a family of Arabidopsis zinc finger protein cDNAs. Plant Mol. Biol., 28, 267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pabo C.O. and Sauer,R.T. (1992) Transcription factors: structural families and principles of DNA recognition. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 2, 1053–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim C.A. and Berg,J.M.(1996) A 2.2 Å resolution crystal structure of a designed zinc finger protein bound to DNA. Nature Struct. Biol., 3, 940–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choo Y. and Klug,A. (1994) Toward a code for the interactions of zinc fingers with DNA: selection of randomized fingers displayed on phage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 11163–11167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choo Y. and Klug,A. (1997) Physical basis of a protein–DNA recognition code. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 7, 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]