Abstract

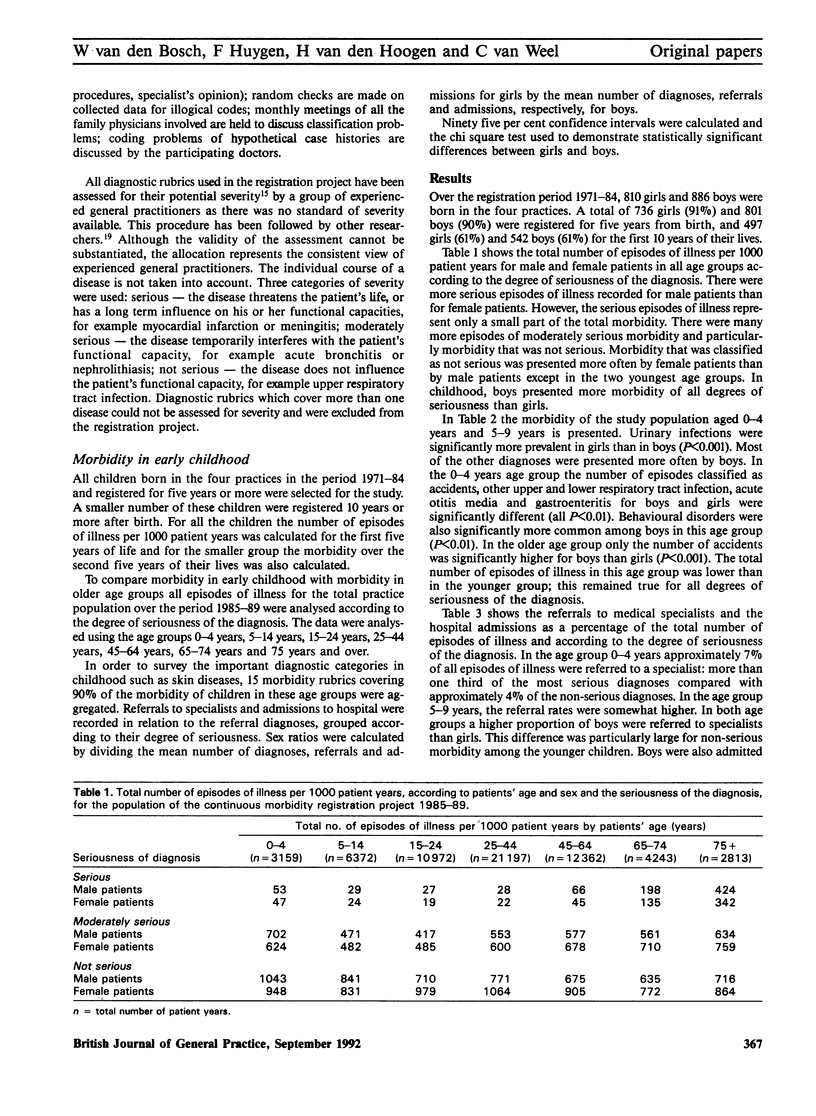

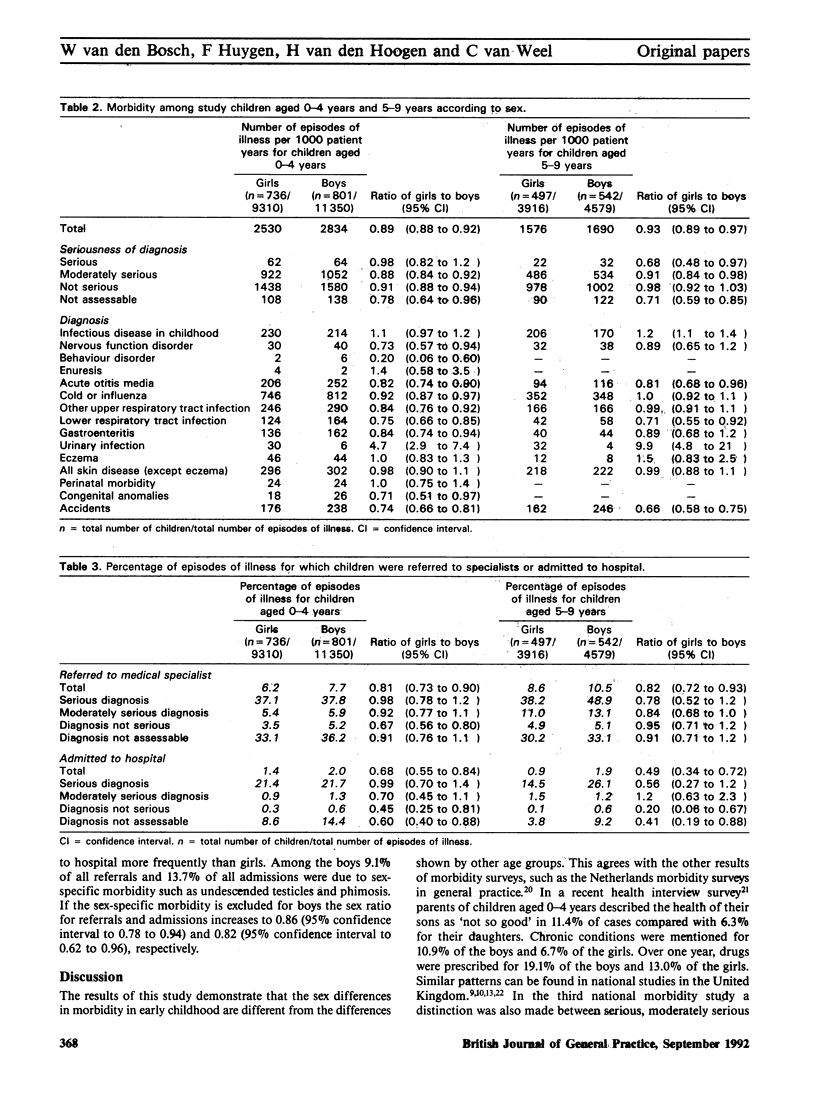

The aim of the study was to investigate the differences in presented morbidity and use of health services among boys and girls in early childhood. The study was performed using data collected by the continuous morbidity registration project of the department of general practice at Nijmegen University. All recorded morbidity, referrals to specialists and admissions to hospitals were recorded by the registration project. The study population included children born in four practices from 1971 to 1984. The children were followed up until the age of five years and if possible until the age of 10 years. The morbidity of the children had been categorized into three levels of seriousness of diagnosis and 15 diagnostic groups as part of the registration project. Boys presented more morbidity than girls in the first years of their lives. For the age group 0-4 years this was true for all levels of seriousness of diagnosis except the most serious. In this younger age group significantly more boys than girls suffered respiratory diseases, behaviour disorders, gastroenteritis and accidents. Girls suffered from more episodes of urinary infection than boys in both age groups. More boys were referred to specialists and admitted to hospital than girls. The findings of this study suggest that not only inborn factors can explain the sex differences in presented morbidity and use of health services in early childhood. In particular, differences between girls and boys in terms of non-serious morbidity and referral and admission rates suggest a different way of handling health problems in boys and girls in early childhood both by parents and doctors.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chojnacka H., Adegbola O. The determinants of infant and child morbidity in Lagos, Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19(8):799–810. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimerl T. S. Organized Curiosity: A Practical Approach to the Problem of Keeping Records for Research Purposes in General Practice. J Coll Gen Pract. 1960 May;3(2):246–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming D. M. Consultation rates in English general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989 Feb;39(319):68–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. Discrimination begins at birth. Indian Pediatr. 1986 Jan;23(1):9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMMOND E. I. STUDIES IN FETAL AND INFANT MORTALITY. II. DIFFERENTIALS IN MORTALITY BY SEX AND RACE. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1965 Aug;55:1152–1163. doi: 10.2105/ajph.55.8.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle L. E., Redmont R., Plummer N., Wolff H. G. II. An Examination of the Relation Between Symptoms, Disability, and Serious Illness, in Two Homogeneous Groups of Men and Women. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1960 Sep;50(9):1327–1336. doi: 10.2105/ajph.50.9.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huygen F. J., van den Hoogen H., Neefs W. J. Gezondheid en ziekte; een onderzoek van gezinnen. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1983 Sep 3;127(36):1612–1619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. E., Lewis M. A. The potential impact of sexual equality on health. N Engl J Med. 1977 Oct 20;297(16):863–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197710202971605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeye R. L., Burt L. S., Wright D. L., Blanc W. A., Tatter D. Neonatal mortality, the male disadvantage. Pediatrics. 1971 Dec;48(6):902–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson C. A. Sex, illness, and medical care. A review of data, theory, and method. Soc Sci Med. 1977 Jan;11(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(77)90141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara F. P., Bergman A. B., LoGerfo J. P., Weiss N. S. Epidemiology of childhood injuries. II. Sex differences in injury rates. Am J Dis Child. 1982 Jun;136(6):502–506. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1982.03970420026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M. Gender and health: an update on hypotheses and evidence. J Health Soc Behav. 1985 Sep;26(3):156–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M. Recent trends in sex mortality differentials in the United States. Women Health. 1980 Fall;5(3):17–37. doi: 10.1300/j013v05n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WASHBURN T. C., MEDEARIS D. N., Jr, CHILDS B. SEX DIFFERENCES IN SUSCEPTIBILITY TO INFECTIONS. Pediatrics. 1965 Jan;35:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron I. Sex differences in illness incidence, prognosis and mortality: issues and evidence. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17(16):1107–1123. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbury R. C. The analysis of family practice workloads by seriousness. J Fam Pract. 1977 Jan;4(1):125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingard D. L., Cohn B. A., Kaplan G. A., Cirillo P. M., Cohen R. D. Sex differentials in morbidity and mortality risks examined by age and cause in the same cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 Sep;130(3):601–610. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingard D. L. The sex differential in morbidity, mortality, and lifestyle. Annu Rev Public Health. 1984;5:433–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.05.050184.002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weel C., van den Bosch W. J., van den HoogenHJ, Smits A. J. Development of respiratory illness in childhood--a longitudinal study in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1987 Sep;37(302):404–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]