Abstract

The anticancer drug cisplatin reacts with DNA leading to the formation of interstrand and intrastrand cross-links that are the critical cytotoxic lesions. In contrast to cells bearing mutations in other components of the nucleotide excision repair apparatus (XPB, XPD, XPG and CSB), cells defective for the ERCC1-XPF structure-specific nuclease are highly sensitive to cisplatin. To determine if the extreme sensitivity of XPF and ERCC1 cells to cisplatin results from specific defects in the repair of either intrastrand or interstrand cross-links we measured the elimination of both lesions in a range of nucleotide excision repair Chinese hamster mutant cell lines, including XPF- and ERCC1-defective cells. Compared to the parental, repair-proficient cell line all the mutants tested were defective in the elimination of both classes of adduct despite their very different levels of increased sensitivity. Consequently, there is no clear relationship between initial incisions at interstrand cross-links or removal of intrastrand adducts and cellular sensitivity. These results demonstrate that the high cisplatin sensitivity of ERCC1 and XPF cells likely results from a defect other than in excision repair. In contrast to other conventional DNA cross-linking agents, we found that the repair of cisplatin adducts does not involve the formation of DNA double-strand breaks. Surprisingly, XRCC2 and XRCC3 cells are defective in the uncoupling step of cisplatin interstrand cross-link repair, suggesting that homologous recombination might be initiated prior to excision of this type of cross-link.

INTRODUCTION

The anticancer drug cisplatin reacts with the N7 atom of purine bases and forms several types of DNA adduct, including DNA interstrand cross-links (ICLs) and (1,2- and 1,3-)intrastrand cross-links (1). Although cisplatin has been widely used in cancer chemotherapy for many years, the critical cytotoxic DNA lesion induced by this drug is still debated. Evidence that both 1,2-intrastrand cross-links (2) and ICLs (3) are the critical DNA lesion has been presented.

The repair of cisplatin intrastrand adducts has been studied in detail using substrates containing defined site-specific cross-links, and cell extracts or purified repair proteins (4–7). The three major cisplatin intrastrand cross-links, 1,2-d(GpG), 1,2-d(ApG) and 1,3d(GpNpG), are all substrates for the mammalian nucleotide excision repair (NER) apparatus (7). The 1,2-cisplatin adducts are, however, much more poorly recognised, adding support to the argument that they are a critical cytotoxic lesion (7,8). The less efficient repair of 1,2-intrastrand adducts is believed to result from the smaller degree of helical distortion these cross-links induce (7,8).

In contrast, very little is known about the repair of cisplatin ICLs, which form between guanines on the complementary DNA strands. A number of recent in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that specialised repair reactions might incise one strand of the cross-linked DNA, and therefore uncouple the ICLs formed by the nitrogen mustard mechlorethamine (9) and those induced following psoralen plus UVA treatment (10,11), initiating repair. These reactions are dependent on the action of the XPF and ERCC1 proteins, but not other members of the mammalian NER apparatus (9–11). ERCC1 and XPF form a tight heterodimeric complex that possesses endonuclease activity at the junctions between single-stranded and double-stranded DNA (12). Two different reactions have been described in biochemical studies of the action of this complex on DNA containing defined ICLs. The first reaction involves the 3′→5′ degradation of the DNA surrounding the ICL on one strand by XPF–ERCC1 (in the presence of RPA), leaving a single uncoupled adducted nucleotide (10) attached to the complementary strand. The second involves incisions by the XPF–ERCC1 complex 5′ and 3′ to the ICL, uncoupling the cross-link (11). This second reaction requires that the ICL bears an unpaired region located immediately 3′ to the ICL and it was suggested that such structures arise during replication and contribute to ICL repair during the S phase of the cell cycle. Very recently it has been demonstrated that human MutSβ might be involved in the recognition and uncoupling step of psoralen ICL repair (13).

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines defective in XPF and ERCC1 are extremely sensitive to cisplatin (14,15), in contrast to cells defective in other components of the NER apparatus. For agents such as mechlorethamine and psoralen plus UVA this seems likely to arise, at least partly, from an inability to uncouple the ICLs produced by these agents by the pathways outlined above (9–11). However, another possible explanation is that ERCC1 and XPF cells are sensitive because they have a dual defect in both the excision repair of cross-links and in homologous recombination. Homologous recombination is known to be an important factor determining survival following treatment with cross-linking drugs (9). Importantly, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologues of XPF and ERCC1 (Rad1 and Rad10) are required for the single-strand annealing subpathway of homologous recombination (16) and there is now good evidence for a role for the mammalian ERCC1–XPF complex in homology-driven recombination (17–19).

We sought to understand the extreme sensitivity of mammalian XPF and ERCC1 cells to cisplatin. Measure ments of the repair capacity for the two candidate critical lesions, ICLs and 1,2-intrastrand cross-links indicated that, although both are reduced in XPF and ERCC1 cells, these processes were also defective in other NER mutants. Consequently, excision repair defects do not seem to account for the extreme sensitivity of ERCC1 and XPF cells to cisplatin. This is in contrast to other cross-linking agents such as the nitrogen mustard mechlorethamine, where specific defects in ICL uncoupling do appear to be responsible for the sensitivity of ERCC1 and XPF cells (9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture conditions

The cell lines used in this study are listed in Table 1. The AA8, UV23, UV42, UV61 and UV96 cell lines were obtained from Dr M. Stefanini (Istituto di Genetica Biochimica et Evoluzionistica, Pavia, Italy), while UV135 was purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collection. The V79, irs1, irs1SF, CHO-K1 and xrs5 cell lines were kindly provided by Prof. J. Thacker (MRC Radiation and Genome Stability Unit, Harwell, UK). All cell lines were grown as monolayers in F12–Ham HEPES medium (Sigma, Poole, UK) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine and 10% foetal calf serum (FCS). Cells were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Trypsin/versine solution was used to detach cells.

Table 1. Chinese hamster cell lines used in this study.

| Mutant cell line | Parent cell line | Defective gene |

|---|---|---|

| UV23 | AA8 | XPB |

| UV42 | AA8 | XPD |

| UV47 | AA8 | XPF |

| UV96 | AA8 | ERCC1 |

| UV135 | AA8 | XPG |

| irs1 | V79 | XRCC2 |

| irs1SF | AA8 | XRCC3 |

| xrs5 | CHO-K1 | XRCC5 |

Chemicals and enzymes

Cisplatin (100 mg/100 ml injectable aqueous stock solution containing 900 mg/100 ml sodium chloride and 100 mg/100 ml mannitol) was obtained from David Bull Laboratories (Australia). Analytical grade mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard or HN2) was purchased from Sigma. All enzymes used were purchased from Promega UK.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was determined using the SRB growth inhibition assay, described in detail previously (9).

Determination of DNA interstrand cross-linking using the Comet assay

This was determined using a modification of the Comet assay (9,20). Exponentially growing cells were treated with the desired concentrations of cisplatin in FCS-free medium for 1 h at 37°C to reduce binding to serum protein. The medium was replaced with fresh complete medium and incubation continued for the required post-incubation time. Cells were then trypsinised and diluted to a density of 2.5 × 104 cells/ml and kept on ice. All drug-treated samples, plus one control, were subjected to 12.5 Gy X-irradiation on ice, and an unirradiated control was included. Microscope slides were pre-coated with 1% (w/v) Type-IA agarose and 0.5 ml of cells were mixed with 1 ml of 1% (w/v) Type-VII agarose and spread over a pre-coated slide in duplicate. A coverslip was added and the agarose was allowed to solidify. The coverslips were removed and the slides were placed in lysis solution (100 mM Na2EDTA, 2.5 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 10.5) containing 1% Triton X-100 at 4°C and incubated for 1 h in the dark. The slides were subsequently washed with ice-cold water for 15 min and this was repeated three times. The slides were then transferred to an electrophoresis tank containing ice-cold alkaline solution (50 mM NaOH, 1 mM Na2EDTA, pH 12.5) and incubated for 45 min in the dark. Electrophoresis was carried out for 25 min at 18 V (0.6 V/cm), 250 mA in the dark. Slides were removed and 1 ml of neutralising solution (0.5 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.5) was added and incubated for 10 min. Each slide was rinsed twice with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and allowed to dry overnight at room temperature. Slides were stained with 2.5 µg/ml propidium iodide and comets were analysed using a Nikon DIAPHOT TDM inverted epifluorescent microscope (consisting of a high pressure mercury vapour light source, a 580 nm dichroic mirror, a 510–560 nm excitation filter and a 590 nm barrier filter) at 20× magnification. Fifty cells were analysed per slide using Komet Assay Software (Kinetic Imaging, Liverpool, UK).

The degree of DNA interstrand cross-linking present in a drug-treated sample was determined by comparing the tail moment of the irradiated drug-treated samples with irradiated untreated samples and unirradiated untreated samples (20). The level of interstrand cross-linking is proportional to the decrease in tail moment (DTM) in the irradiated drug-treated sample compared to the irradiated untreated control. The DTM is calculated by the following formula:

% DTM = [1 – (TMdi – TMcu)/(TMci – TMcu)] × 100

where TMdi is the mean tail moment of the drug-treated, irradiated sample, TMci is the mean tail moment of the irradiated control sample and TMcu is the mean tail moment of the unirradiated control sample.

Measurement of cisplatin intrastrand cross-links by ELISA

Exponentially growing cells were treated with cisplatin for 1 h and incubated in drug-free medium for various times or assayed immediately. Cells were washed with PBS twices and genomic DNA was isolated using a Qiagen Genomic DNA Tip. Genomic DNA was digested with HindIII, ethanol precipitated and resuspended in water. The DNA concentration was determined fluorimetrically.

The competitive ELISA developed by Tilby et al. (21,22) was used with certain modifications. ELISA plates (high-bind 96-well flat bottom; Greiner) were prepared the day before by coating the wells with platinated DNA. Denatured calf thymus DNA treated with cisplatin to give an adduct level of 35.2 µM/g DNA (provided by M. J. Tilby, University of Newcastle, UK) was diluted 1:2000 in coating buffer (1 M sodium chloride, 50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.02% sodium azide) and 50 µl of this solution was incubated in each well at 37°C overnight. ELISA wells were then blocked with 150 µl/well BSA solution (1% w/v in PBS) for at least 30 min at room temperature. Assay samples and the standard (kindly provided by M. J. Tilby) were incubated in boiling water for 5 min to increase immunoreactivity and serially diluted in DB buffer (50 mM sodium chloride, 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0). ICR4 antibody was diluted 1:60 000 in PBS containing 0.2% BSA, 90 mM sodium chloride, 0.2% Tween-20 and 0.2 mg/ml phenol red and 55 µl of this solution was mixed with 55 µl of serially diluted assay samples and the standard. After 30 min incubation at 37°C, 50 µl aliquots were transferred to coated 96-well ELISA plates and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. All samples were assayed in duplicate. Each assay plate included wells without sample (only antibody) and wells without antibody (only sample/standard). Following five washes with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, bound antibody was determined using 50 µl/well biotinylated goat anti-rat antibody (Sigma) diluted 1:2500 in PBS containing 1% BSA, 0.2% Tween-20. Following 30 min incubation at 37°C, plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 and wells were incubated with 50 µl of streptavidin–β-galactosidase reagent (Boehringer) (stock dissolved in 1 ml of PBS and diluted 1:10 000 in PBS containing 10 mM MgCl2, 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20). Following 30 min incubation at 37°C, plates were washed seven times and incubated with 50 µl/well 4-methyl-umbelliferyl β-d-galactoside (Sigma) (80 µg/ml solution made in PBS containing 10 mM MgCl2 and azide). Plates were covered and placed in the dark for 2–4 h. To measure the fluorescence of each well, plates were read at 360 nm emission and 465 nm excitation using a Tecan Spectrafluor Plus plate reader. The mean background reading was subtracted from all the readings and the percentage inhibition of maximum fluorescence was calculated for each serial dilution of the assay samples and the standard. Cisplatin intrastrand adduct levels were then calculated as described by Tilby et al. (21).

Analysis of double-strand breaks (DSBs) by pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

Cells growing in a monolayer were treated with cisplatin for 1 h, washed with 10 ml of PBS and incubated with fresh medium for the required repair time. Cells were trypsinised, 3 × 106 cells were harvested and PFGE plugs were prepared using the Bio-Rad Mammalian CHEF Genomic Plug Kit, as instructed by the manufacturer. PFGE was performed with a 0.7% gel (Pulse Field Certified Agarose; Bio-Rad) in 0.25× TBE buffer using a Biometra Rotaphor Type V apparatus. Electrophoresis runs were for 120 h at 14°C with the following parameters: interval 5000–1000 s log, angle 110–100° linear, voltage 50–45 V linear. On completion the gels were stained with 2 µg/ml ethidium bromide for 1 h, destained overnight with water and photographed. Semi-quantitative data were obtained by measuring the absolute integrated optical density of each lane using Gel Pro Analyser (Media Cybernetics) and calculating the percentage of DNA released from the DNA plug.

RESULTS

ERCC1 and XPF cells are highly sensitive to cisplatin

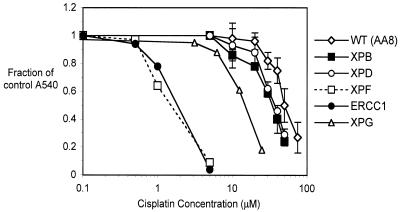

Exponentially growing cells were treated with increasing concentrations of cisplatin for 1 h and growth inhibition measured using the SRB assay. As shown in Figure 1, the UV47 and UV96 cell lines, defective in XPF and ERCC1, respectively, showed extreme sensitivity to cisplatin compared to their isogenic parent cell line AA8. When IC50 values were compared, XPF and ERCC1 mutants were 40- and 37-fold more sensitive to cisplatin than their parent cell line, indicating the crucial role of this structure-specific nuclease in the repair of cisplatin-induced DNA damage. In contrast, the XPB, XPD and XPG mutant cells were only 1.4-, 1.3- and 3.1-fold more sensitive than the parent cell line, respectively, suggesting a minor role for these NER proteins in the response to critical cisplatin lesions.

Figure 1.

Cisplatin sensitivity of parental AA8 cells and NER mutants XPB (UV23), XPD (UV42), XPF (UV47), ERCC1 (UV96) and XPG (UV135). Exponentially growing cells were treated with increasing concentrations of cisplatin for 1 h, incubated in drug-free medium for 3 days and stained with SRB. Fraction of growth inhibition was calculated for each dose as described in Materials and Methods. All results are the means of at least three independent experiments and error bars show the standard error of the mean.

Induction and repair of DNA ICLs

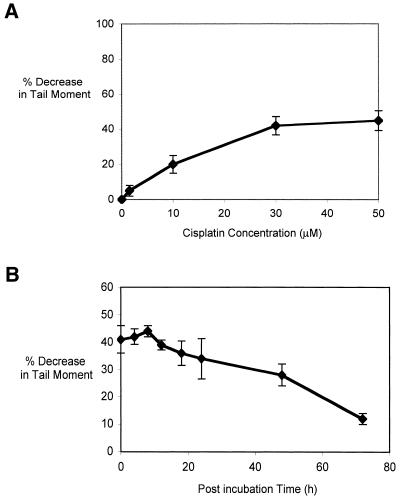

DNA ICLs are a potentially cytotoxic (3), but quantitatively minor, adduct (∼1% of the total lesions) formed by cisplatin (1). Using a modification of the Comet assay, which permits detection of ICLs at the single cell level in vivo, the induction and repair kinetics of cisplatin-induced ICLs were studied. Prior to cell lysis the cells receive a fixed dose of X-rays to induce random strand breakage. The presence of ICLs retards migration of the irradiated DNA during electrophoresis, resulting in a reduced tail moment compared to the non-drug-treated control. Figure 2A shows the percentage decrease in tail moment with increasing concentrations of cisplatin for the parental, repair-proficient AA8 cell line. A decrease in tail moment occurs linearly up to 30 µM, but no further significant increase was observed at 50 µM. No single-strand breaks were seen in unirradiated samples treated with increasing doses of cisplatin (data not shown).

Figure 2.

(A) Decrease in comet tail moment (TM) with increasing concentration of cisplatin. AA8 cells were treated with increasing doses of cisplatin for 1 h and analysed immediately. For each drug concentration, the TM of 50 comets was measured and the mean values were calculated. The percentage decrease in TM in comparison with untreated samples was then calculated (Materials and Methods). The results shown above are the means of three independent experiments and error bars show the standard error of the mean. (B) The early repair kinetics of ICL repair in AA8 cells treated with 50 µM cisplatin for 1 h and samples removed at increasing times for Comet analysis. The results presented are the means of at least three independent experiments and error bars show the standard error of the mean. (C) Induction and repair of cisplatin ICLs in parental and NER mutant cell lines. WT (AA8), XPB (UV23), XPG (UV135), XPF (UV47) and ERCC1 (UV96) cells were treated with 50 µM cisplatin for 1 h and incubated in drug-free medium for 24, 48 and 72 h to allow repair. Percentage decrease in TM in comparison with untreated samples was calculated as above. The results presented are the means of at least three independent experiments and error bars show the standard error of the mean.

The kinetics of ICL induction and repair in the NER mutants were examined following a 1 h treatment with 50 µM cisplatin (Fig. 2B). This dose gives 50% inhibition of growth in AA8 cells and induces a readily detectable level of ICLs (∼40% decrease in tail moment). As previously reported (3), ICL levels peak at ∼8 h, followed by gradual repair that is still incomplete at 72 h post-treatment incubation. AA8 and its isogenic NER mutant derivatives (XPB, XPG, XPF and ERCC1) were treated with 50 µM cisplatin for 1 h and the level of ICLs assessed following 0, 24, 48 and 72 h post-incubation in drug-free medium (Fig. 2C). A comparable level of ICLs was observed in all these cell lines immediately following the 1 h treatment, demonstrating that the differences in sensitivity are not due to differences in the induction of ICLs. Consistent with their extreme sensitivities, the XPF and ERCC1 mutants were defective in the uncoupling step, or incision, of cisplatin-induced ICLs. Surprisingly, the much less sensitive XPB and XPG mutants were also defective in the uncoupling of ICLs. The lack of correlation between sensitivity to cisplatin and ICL incision capacity implies that the differential sensitivities of the NER mutants to cisplatin are not due to a difference in their ability to initiate repair of the ICLs induced by this drug.

Induction and repair of cisplatin 1,2-intrastrand cross-links

Since no definite correlation was observed between cisplatin sensitivity and the uncoupling of ICLs in any of the NER mutants, the induction and repair of intrastrand cisplatin adducts was investigated in the parent and NER mutant cell lines. These adducts were measured using a competitive ELISA method developed by Tilby et al. (21) employing a monoclonal antibody which recognises cisplatin 1,2-intrastrand cross-links (22; M.Tilby, personal communication).

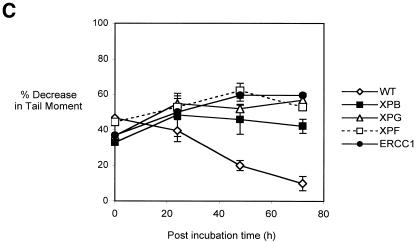

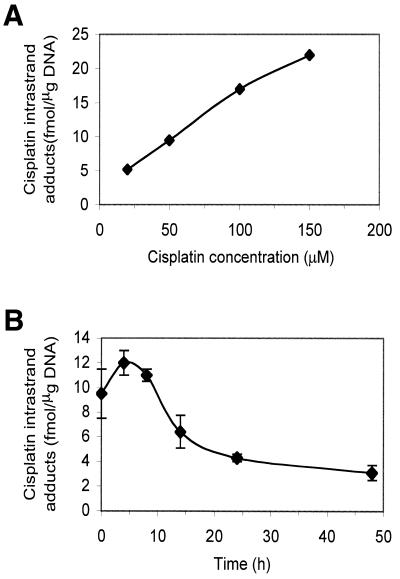

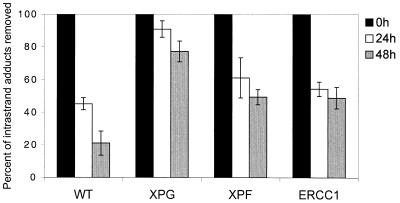

In Figure 3A, the AA8 parental cell line was treated with increasing doses of cisplatin for 1 h and a linear increase in the induction of cisplatin intrastrand adducts was observed. In subsequent experiments 50 µM cisplatin, the IC50 value in the AA8 parent cell line, was used as it gave a readily measurable level of adducts (9.5 fmol/µg DNA). The repair kinetics of cisplatin intrastrand cross-links in the AA8 parent cell line are shown in Figure 3B. Following a 1 h drug treatment, the level of intrastrand adducts peaked after 4 h post-treatment incubation, consistent with previous reports (2). At 24 and 48 h following drug removal 64 and 74% of the adducts were eliminated, respectively. Figure 4 shows the post-treatment elimination of cisplatin 1,2-intrastrand cross-links in the NER mutants. The XPG mutant was most severely defective in the elimination of these adducts. At 48 h following drug removal, 3.7 times more intrastrand adduct remained in the XPG-defective cells than the parent cell line. The XPF and ERCC1 mutants were also defective (both 2.3-fold). As with cisplatin ICLs, it is again striking that there is little correlation between ability to eliminate the cisplatin lesion, this time the intrastrand cross-link, and cellular sensitivity amongst NER mutants. The extreme sensitivity of the ERCC1 and XPF cell lines strongly suggests that they have a dual deficiency in excision repair and another pathway vital for the repair and/or tolerance of critical cisplatin–DNA adducts.

Figure 3.

(A) Induction of cisplatin intrastrand cross-links following treatment of AA8 cells with increasing doses of cisplatin. Exponentially growing AA8 cells were treated with cisplatin for 1 h and the level of intrastrand adducts were analysed immediately using competitive ELISA. (B) Kinetics of cisplatin intrastrand adduct removal in AA8 cells. Exponentially growing AA8 cells were treated with 50 µM cisplatin for 1 h, incubated in drug-free medium for the stated times and the level of intrastrand adducts quantified using competitive ELISA. The results are the means of five independent experiments and the error bars show the standard error of the mean.

Figure 4.

Elimination of cisplatin intrastrand cross-links in wild-type (AA8) cells and NER mutants XPG (UV135), XPF (UV47) and ERCC1 (UV96). Cells were treated with 50 µM cisplatin for 1 h and adduct levels quantified immediately following drug removal (0 h) and 24 and 48 h later using competitive ELISA. The results presented are the means of between three and five individual experiments and error bars are the standard error of the mean.

Importance of homology-driven recombination in response to cisplatin

There is good evidence that homologous recombination plays a role in the cellular response to cisplatin in lower organisms (23,24). Therefore, defects in recombination as well as NER may account for the extreme cisplatin hypersensitivity of ERCC1 and XPF mammalian cells.

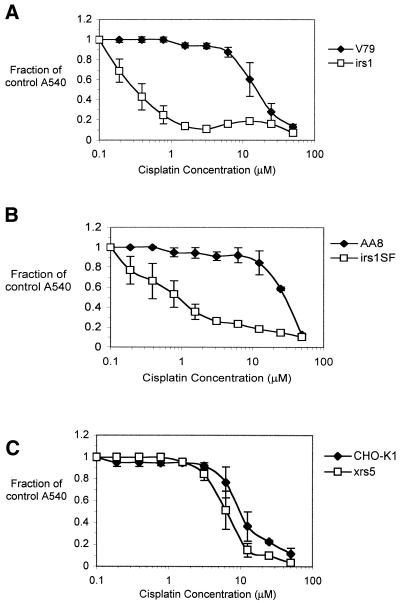

XRCC2 (irs1) and XRCC3 (irs1SF) cells, defective for two Rad51-related recombination factors, are derived from the V79 and AA8 parent cell lines, respectively, and xrs5 cells [XRCC5 mutant cells, defective in the Ku86 protein, required for non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)] are derived from CHO-K1 cells. The cisplatin sensitivities of these mutants, together with their parents, are shown in Figure 5. Confirming published data (25), the XRCC2 and XRCC3 mutants showed extreme sensitivity to cisplatin, having 50- and 38-fold higher sensitivities compared to their parent cell lines (Fig. 5A and B, respectively). These values are similar to those obtained with the XPF and ERCC1 cells. In contrast, the NHEJ mutant xrs5 showed only a slight increase in sensitivity (1.7-fold) compared to the parent cell line, suggesting that the involvement of the NHEJ pathway in the repair of cisplatin DNA damage is minor (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Cisplatin sensitivity of CHO recombination mutants. (A) XRCC2 (irs1) and its parental cell line V79; (B) XRCC3 (irs1SF) and parental AA8 cells; (C) the NHEJ mutant XRCC5 (xrs5) and its parental cell line CHO-K1. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of cisplatin for 1 h, incubated in drug-free medium for 3 days and stained with SRB. All results are the means of at least three independent experiments and error bars are the standard error of the mean.

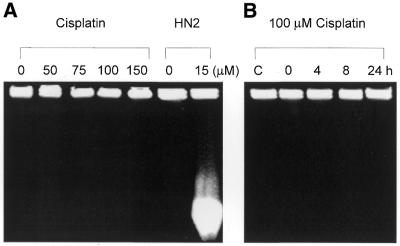

In S.cerevisiae the repair of psoralen- and mechlorethamine- induced DNA ICLs involves the formation of DSBs in replicating cells (24,26,27). Similarly, we have clearly demonstrated that DSBs also arise in mammalian (CHO) cells during processing of mechlorethamine-induced ICLs (9). However, despite these suggestions, the induction of DSBs during the processing of cisplatin-induced DNA damage has not been investigated in detail. To address this, the induction of DSBs following cisplatin treatment was examined using PFGE. Exponentially growing AA8 cells were treated with increasing doses of cisplatin for 1 h and analysed by PFGE. DNA from cells treated with an IC50 dose (15 µM) of mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard) was included as a positive control. No DSBs were observed following cisplatin treatment at 150 µM (three times the IC50) (Fig. 6A). As expected, the ICLs induced by nitrogen mustard resulted in the accumulation of DSBs, producing a lower molecular weight smear of DNA released from the plugs. To investigate whether cisplatin DSBs arise over longer times, AA8 cells were treated with 100 µM cisplatin for 1 h and DSBs were monitored over a 0–24 h period. No DSBs were observed at any of the time points analysed (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

(A) PFGE analysis of DNA from cells treated with increasing doses of cisplatin. Exponentially growing AA8 cells were treated with the stated concentrations of cisplatin or 15 µM nitrogen mustard for 1 h and immediately analysed for the presence of DSBs on pulsed field gels. (B) PFGE analysis of DNA from cisplatin-treated cells subject to further post-treatment incubation. Exponentially growing AA8 cells were treated with 100 µM cisplatin for 1 h and incubated in drug-free medium for the stated time prior to PFGE analysis. Lane C contained DNA from mock- treated cells subject to 24 h post-treatment incubation. (C) ICL uncoupling in recombination-defective cells. irs1SF (XRCC3 mutant) cells and their isogenic parent AA8 were treated with 50 µM cisplatin for 1 h and incubated in drug-free medium for 24, 48 and 72 h to allow repair. Percentage decrease in TM in comparison with untreated samples was calculated as above. The results presented are the means of at least three independent experiments and error bars show the standard error of the mean.

The XRCC2 and XRCC3 homologous recombination mutants are highly sensitive to nitrogen mustard and this correlates with an impaired ability to repair HN2-induced DSBs (9). XRCC2 and XRCC3 mutants are also extremely sensitive to cisplatin. If the level of induction of DSBs by cisplatin is very low and if they are readily repaired in recombination-proficient AA8 cells, it is possible that this PFGE approach is not sensitive enough to detect these DSBs. If the high sensitivity of XRCC2 and XRCC3 mutants to cisplatin is associated with impaired repair of low levels of DSBs, these mutants should accumulate DSBs following cisplatin treatment. To investigate this possibility, the induction of DSBs was examined in the wild-type (AA8 and V79), XRCC2 and XRCC3 mutants over a 24 h time period, following 1 h treatment with up to 100 µM cisplatin. These experiments failed to demonstrate the occurrence of any DSBs (data not shown). These results suggest that DSBs do not occur in the processing of cisplatin-induced DNA damage, in contrast to other common agents that induce ICLs.

Finally, we determined whether a recombination mutant (XRCC3, irs1SF) is competent to initiate ICL repair, specifically at the cross-link uncoupling stage. Cells were treated with 50 µM cisplatin for 1 h and ICL uncoupling followed during 72 h post-treatment incubation in complete medium, using the modified Comet assay. XRCC3 cells were defective in the uncoupling of ICLs (Fig. 6C). This surprising result indicates that the uncoupling stage of cisplatin ICL repair might be dependent upon the formation of early recombination intermediates. This contrasts with nitrogen mustard, where XRCC3-defective cells have been shown to be capable of incising the ICLs induced by this agent (9).

DISCUSSION

It has been established that both NER and homology-driven recombination activities are important for the elimination of cisplatin DNA adducts in Escherichia coli (23,28) and yeast (24,29) cells. In agreement with previous reports (14,15), the results obtained in this study confirm that XPF- and ERCC1-defective mammalian cells are extremely sensitive to cisplatin. In contrast, the other NER mutants considered here (XPB, XPD, XPG and CSB) do not possess this extreme sensitivity (15). This implies that the XPF–ERCC1 structure-specific nuclease plays a key role in the repair of critical cisplatin lesions or repair intermediates. To address whether the excision repair of a particular lesion is specifically reduced or absent in XPF- and ERCC1-defective cells we have measured the capacity of a set of NER mutants to eliminate two cisplatin adducts which constitute critical DNA damage induced by this agent; the ICL and 1,2-intrastrand cross-link.

Both the highly sensitive XPF and ERCC1 mutants and the slightly sensitive XPB and XPG mutants were defective in the uncoupling of ICLs, indicating that a full complement of NER proteins is required for the excision of cisplatin ICLs. No clear correlation was observed between cellular sensitivity and ICL uncoupling capacity. Although the XPB and XPG mutants were completely defective in the uncoupling step of ICL repair, they were only 1.4- and 3.1-fold more sensitive to cisplatin than the parent cell line, compared to a 37–40-fold increase in sensitivity observed in XPF and ERCC1 mutants. Meyn et al. (30) demonstrated that another ERCC1 mutant CHO cell line, UV20, was extremely sensitive to cisplatin and defective in the uncoupling of interstrand cross-links, and this was taken to demonstrate a direct relationship between sensitivity and ICL repair. However, the ICL repair capacity of the less sensitive NER-defective cell lines was not investigated. Here, for the first time, we show that, in addition to XPF–ERCC1, other components of the NER machinery are essential for the excision of cisplatin ICLs in vivo. The data suggest that ICLs are not, by themselves, the critical DNA lesion induced by cisplatin since an inability to repair this lesion only leads to a very modest increase in cellular sensitivity.

These results are very different from those obtained with nitrogen mustard (9), where a direct correlation between mutant sensitivity and the ability to uncouple ICLs was evident. In this case the XPB and XPG cells were only slightly drug sensitive and were proficient in the uncoupling of nitrogen mustard-induced ICLs, whereas the highly sensitive XPF and ERCC1 cells were severely defective. In addition, recent biochemical studies employing purified proteins (10,11) have shown that the uncoupling step of psoralen ICL repair can be achieved by the XPF–ERCC1 nuclease in the absence of other factors (except RPA in the former study). A further cross-link-specific excision reaction has been identified by Bessho et al. (31). Here the complete human excision nuclease makes dual incisions 5′ to a psoralen cross-link on one strand of the damaged DNA only. Although the authors state that this intermediate might act as an initiation signal for recombination, such a reaction does not release the cross-link and therefore probably does not represent the uncoupling reactions seen in our study. Further biochemical studies employing defined cisplatin ICL-containing substrates are required to elucidate the molecular nature of this reaction.

A surprising observation was that the XRCC2 and XRCC3 mutants were unable to uncouple the cisplatin ICLs (Fig. 6C). This raises the possibility that homologous recombination is initiated prior to the incisions which uncouple the cisplatin cross-link and that the incision reactions depend upon an early recombination intermediate being formed. Perhaps a homology search, requiring the Rad51 family of proteins (which includes Xrcc2 and Xrcc3), precedes the uncoupling reaction. While this is possible, it should be emphasised that studies of the enzymology of mammalian homologous recombination have yet to identify such reactions. Nevertheless, given that the uncoupling incisions for cisplatin ICLs appear significantly different to those observed for nitrogen mustard ICLs this coordination might help explain the differing requirements for NER proteins in the uncoupling step.

The removal of cisplatin 1,2-intrastrand cross-links was reduced in all the NER mutants tested. Our results are consistent with those obtained using purified proteins to reconstitute the excision repair of cisplatin intrastrand cross-links in defined substrates (4–8). We showed that XPG, ERCC1 and XPF mutant cell lines were all significantly defective in the repair of this class of adduct. Again, the absence of a correlation between sensitivity and excision repair capacity is apparent. This strongly suggests that the ERCC1–XPF complex plays an additional role in the repair of cisplatin DNA damage.

Confirming published data (25), XRCC2 and XRCC3 mutants were extremely sensitive to cisplatin, demonstrating that homology-driven recombination plays a major role in the repair of cisplatin DNA damage. Several other emerging homologous recombination components, including Rad51, Brca1 and Brca2, have also been implicated in the mammalian response to cisplatin DNA damage (32–34) and mutations in these genes render cells sensitive to cisplatin. Brca1 promotes assembly of subnuclear Rad51 foci following treatment of mouse embryonic stem cells with cisplatin (33). The recently generated Rad51 family mutant Rad51B–/–, derived from chicken DT40 cells, shows hypersensitivity to cisplatin (32). ERCC1 and XPF must now also be considered as candidates for a role in the recombinational processing of cisplatin adducts.

A recent study by Zdraveski et al. (23) demonstrated that E.coli mutants defective in both daughter-strand gap and DSB homologous recombination pathways are sensitive to cisplatin, providing evidence that DSBs may arise during the repair of cisplatin ICLs in this organism. Surprisingly, however, no DSB formation was observed during the processing of cisplatin-induced DNA damage in this study, even in XRCC2 and XRCC3 cells. Previous studies in our laboratory, and the work of others, has indicated that the induction of DSBs by psoralen and nitrogen mustard ICLs might be due to the collapse of replication forks (9,24,35). Significantly, mammalian cells possess enzymes able to replicate DNA containing cisplatin adducts. DNA polymerase β can perform extensive bypass synthesis on platinated DNA in vitro (36) and DNA polymerase η, which is defective in XPV patients, can also bypass cisplatin intrastrand cross-links efficiently and with high fidelity (37). Therefore, the absence of DSBs following cisplatin treatment could be a result of the bypass of cisplatin adducts or indicate that when replication forks encounter cisplatin cross-links DSBs do not result. It is conceivable that the ERCC1–XPF nuclease plays some role at this stage, perhaps in the recombinational restart of replication.

Collectively, these studies show that ERCC1 and XPF are vital to the mammalian cell response to this important anticancer agent. It appears that the major contribution made by these factors is largely independent of their role in excision repair. It is highly unlikely that an additional, as yet uncharacterised, critical cisplatin adduct exists which relies entirely upon XPF–ERCC1 for repair. Future work will focus on identifying defects in cisplatin-induced recombination pathways and end-points resulting from loss of ERCC1 and XPF. Defined intrachromosomal repeat recombination substrates have already proved valuable in defining spontaneous recombination defects in ERCC1 and XPF cells (17,18) and the use of these constructs for the analysis of recombination events induced by different DNA-damaging agents (and the requirement for individual mammalian recombination factors) should be explored. The mechanisms by which homology-driven recombination pathways process cisplatin lesions need to be elucidated since the ability to selectively sensitise cells to cisplatin by inhibiting this pathway could substantially enhance the therapeutic efficacy of this drug.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are extremely grateful to Dr Mike Tilby for the kind gift of the cisplatin adduct antibodies and guidance in setting up the ELISA. We would also like to thank Dr M. Stefanini and Prof. J. Thacker for providing the CHO cell lines. This work was supported by the Cancer Research UK Programme grant SP2000/0402, by a PhD studentship to I.De S. from the Clinical Research and Development Committee, UCL, and by a Royal Society Research Fellowship to P.J.McH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Comess K.M. and Lippard,S.J. (1993) Molecular aspects of platinum-DNA interactions. In Neidle,S. and Waring,M.J. (eds), Molecular Aspects of Anticancer Drug-DNA Interactions. Macmillan Press, Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK, pp. 134–168.

- 2.Fichtinger-Schepman A.M., van Dijk-Knijnenburg,H.C.M., van der Veld-Visser,S.D., Brends,F. and Baan,R.A. (1995) Cisplatin– and carboplatin–DNA adducts: is PT-AG the cytotoxic lesion? Carcinogenesis, 16, 2447–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zwelling L.A., Anderson,T. and Kohn,K.W. (1979) DNA-protein and DNA interstrand cross-linking by cis- and trans-platinum(II) diamminedichloride in L1210 mouse leukemia cells and relation to cytotoxicity. Cancer Res., 39, 365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson J. and Wood,R.D. (1989) Repair synthesis by human cell extracts in DNA damaged by cis- and trans-diamminedichloroplatinum(II). Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 8073–8091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans E., Fellows,J., Coffer,A. and Wood,R.D. (1997) Open complex formation around a lesion during nucleotide excision repair provides a structure for cleavage by human XPG protein. EMBO J., 16, 625–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans E., Moggs,J.G., Hwang,J.R., Egly,J. and Wood,R.D. (1997) Mechanism of open complex and dual incision formation by human nucleotide excision repair factors. EMBO J., 16, 6559–6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zamble D.B., Mu,D., Reardon,J.T., Sancar,A. and Lippard,S.J. (1996) Repair of cisplatin–DNA adducts by the mammalian excision nuclease. Biochemistry, 35, 10004–10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moggs J.G., Szymkowski,D.E., Yamada,M., Karran,P. and Wood,R.D. (1997) Differential human nucleotide excision repair of paired and mispaired cisplatin–DNA adducts. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 480–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Silva I.U., McHugh,P.J., Clingen,P.H. and Hartley,J.A. (2000) Defining the roles of nucleotide excision repair and recombination in the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 7980–7990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mu D., Bessho,T., Nechev,L.V., Chen,D.J., Harris,T.M., Hearst,J.E. and Sancar,A. (2000) DNA interstrand cross-links induce futile repair synthesis in mammalian cell extracts. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 2446–2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuraoka I., Kobertz,W.R., Ariza,R.R., Biggerstaff,M., Essigmann,J.M. and Wood,R.D. (2000) Repair of an interstrand DNA cross-link initiated by ERCC1-XPF repair/recombination nuclease. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 26632–26636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Laat W.L., Appeldoorn,E., Jaspers,N.G.J. and Hoeijmakers,J.H.J. (1998) DNA structural elements required for ERCC1-XPF endonuclease activity. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 7835–7842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang N., Lu,X., Zhang,X., Peterson,C.A. and Legerski,R.J. (2002) hMutSβ is required for the recognition and uncoupling of psoralen interstrand cross-links in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol., 7, 2388–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoy C.A., Thompson,L.H., Mooney,C.L. and Salazar,E.P. (1985) Defective DNA cross-link removal in Chinese hamster cell mutants hypersensitive to bifunctional alkylating agents. Cancer Res., 45, 1737–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damia G., Imperatori,L., Stefanini,M. and D’Incalci,M. (1996) Sensitivity of CHO mutant cell lines with specific defects in nucleotide excision repair to different anti-cancer agents. Int. J. Cancer, 66, 779–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivanov E.L. and Haber,J.E. (1995) RAD1 and RAD10, but not other excision repair genes, are required for double-strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 2245–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sargent R.G., Rolig,R.L., Kilburn,A.E., Adair,G.M., Wilson,J.H. and Nairn,R.S. (1997) Recombination-dependent deletion formation in mammalian cells deficient in the nucleotide excision repair gene ERCC1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 13122–13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sargent R.G., Meservy,J.L, Perkins,B.D., Kilburn,A.E., Intody,Z., Adair,G.M., Nairn,R.S. and Wison,J.H. (2000) Role of the nucleotide excision repair gene ERCC1 in formation of recombination-dependent rearrangements in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3771–3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adair G.M., Rolig,R.L., Moore-Faver,D., Zabelshansky,M., Wilson,J.H. and Nairn,R.S. (2000) Role of ERCC1 in removal of long non-homologous tails during targeted homologous recombination. EMBO J., 19, 5552–5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spanswick V.J., Hartley,J.M., Ward,T.H. and Hartley,J.A. (1999) Measurement of drug-induced interstrand crosslinking using single-cell gel electrophoresis (Comet) assay. In Brown,R. and Boger-Brown,U. (eds), Methods in Molecular Medicine, Vol. 28, Cytotoxic Drug Resistance Mechanisms. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Tilby M.J., Styles,J.M. and Dean,C.J. (1987) Immunological detection of DNA damage caused by melphalan using monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res., 47, 1542–1546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tilby M.J., Johnson,C., Knox,R.J., Cordell,J., Roberts,J.J. and Dean,C.J. (1991) Sensitive detection of DNA modifications induced by cisplatin and carboplatin in vitro and in vivo using a monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res., 51, 123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zdraveski Z.Z., Mello,J.A., Marnus,M.G. and Essigmann,J.M. (2000) Multiple pathways of recombination define cellular responses to cisplatin. Chem. Biol., 7, 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McHugh P.J., Sones,W.R. and Hartley,J.A. (2000) Repair of intermediate structures produced at DNA interstrand cross-links in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 3425–3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caldecott K. and Jeggo,P. (1991) Cross-sensitivity of gamma-ray-sensitive hamster mutants to cross-linking agents. Mutat. Res., 255, 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magana-Schwencke N., Henriques,J.A., Chanet,R. and Moustacchi,E. (1982) The fate of 8-methoxypsoralen photoinduced crosslinks in nuclear and mitochondrial yeast DNA: comparison of wild-type and repair-deficient strains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 79, 1722–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jachymczyk W.J., von Borstel,R.C., Mowat,M.R. and Hastings,P.J. (1981) Repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires two systems for DNA repair: the RAD3 system and the RAD51 system. Mol. Gen. Genet., 182, 196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Husain I., Chaney,S.G. and Sancar,A. (1985) Repair of cis-platinum-DNA adducts by ABC excinuclease in vivo and in vitro. J. Bacteriol., 163, 817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilborn F. and Brendel,M. (1989) Formation and stability of interstrand cross-links induced by cis- and trans-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) in the DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains differing in repair capacity. Curr. Genet., 16, 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyn R.E., Jenkins,S.F. and Thompson,L.H. (1982) Defective removal of DNA cross-links in a repair-deficient mutant of Chinese hamster cells. Cancer Res., 42, 3106–3110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bessho T., Mu,D. and Sancar,A. (1997) Initiation of DNA interstrand cross-link repair in humans: the nucleotide excision repair system makes dual incisions 5′ to the cross-linked base and removes a 22- to 28-nucleotide-long damage-free strand. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 6822–6830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takata M., Sasaki,M.S., Sonoda,E., Fukushima,T., Morrison,C., Albala,J.S., Swagemakers,S.M., Kanaar,R., Thompson,L.H. and Takeda,S. (2000) The Rad51 paralog Rad51B promotes homologous recombinational repair. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 6476–6482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharyya A., Ear,U.S., Koller,B.H., Weichselbaum,R.R. and Bishop,D.K. (2000) The breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 is required for subnuclear assembly of Rad51 and survival following treatment with the DNA cross-linking agent cisplatin. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 23899–23903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan S.S., Lee,S.Y., Chen,G., Song,M., Tomlinson,G.E. and Lee,E.Y. (1999) BRCA2 is required for ionizing radiation-induced assembly of Rad51 complex in vivo. Cancer Res., 59, 3547–3551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akkari Y.M.N., Bateman,R.L., Reifsteck,C.A., Olson,S.B. and Grompe,M. (2000) DNA replication is required to elicit cellular responses to psoralen-induced DNA interstrand cross-links. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 8283–8289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaisman A. and Chaney,S.G. (2000) The efficiency and fidelity of translesion synthesis past cisplatin and oxaliplatin GpG adducts by human DNA polymerase beta. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 13017–13025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masutani C., Kusumoto,R., Iwai,S. and Hanaoka,F. (2000) Mechanisms of accurate translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase η. EMBO J., 19, 3100–3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]