Abstract

The DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) complex, which is composed of a DNA-dependent kinase subunit (DNA-PKcs) and the Ku70/80 heterodimer, is involved in DNA double-strand break repair by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Ku70/80 interacts with the Werner syndrome protein (WRN) and stimulates WRN exonuclease activity. To investigate a possible function of WRN in NHEJ, we have examined the relationship between DNA-PKcs, Ku and WRN. First, we showed that WRN forms a complex with DNA-PKcs and Ku in solution. Next, we determined whether this complex assembles on DNA ends. Interestingly, the addition of WRN to a Ku:DNA-PKcs:DNA complex results in the displacement of DNA-PKcs from the DNA, indicating that the triple complex WRN:Ku:DNA-PKcs cannot form on DNA ends. The displacement of DNA-PKcs from DNA requires the N- and C-terminal regions of WRN, both of which make direct contact with the Ku70/80 heterodimer. Moreover, exonuclease assays indicate that DNA-PKcs does not protect DNA from the nucleolytic action of WRN. These results suggest that WRN may influence the mechanism by which DNA ends are processed.

INTRODUCTION

Werner syndrome (WS) is a premature aging disease (progeria) with features typical of normal aging such as graying and loss of hair, atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, type II diabetes mellitus and vascular disease, as well as an unusually high incidence of tumors (1–3). The first signs of this disorder appear after puberty and the full symptoms become apparent in individuals 20–30 years of age. Myocardial infarction and cancer are the most common causes of death in WS patients, who have a median age of death of ∼47 years. Primary fibroblasts from WS individuals show decreased lifespan and divide approximately half the number of times as normal fibroblasts. WS cells show an elevated rate of chromosomal translocations and extensive genomic deletions (4–6). WS is caused by mutations in a single gene that encodes a 1432 amino acid protein (Werner syndrome protein, WRN). WRN has a central domain that shows strong homology to the RecQ helicases (7,8) and the N-terminal region of WRN is highly homologous to the nuclease domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I and ribonuclease D (9). Helicase and exonuclease activities with a 3′→5′ directionality have been demonstrated in vitro using the recombinant protein (10–15).

Our biochemical results and those from Bohr and colleagues show that WRN interacts with the Ku70/80 heterodimer (Ku) (16,17) and that this interaction alters the properties of WRN exonuclease activity (17). Ku70/80 is a factor required for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) (18–20). Furthermore, the localization of Ku70/80 at telomeres has suggested that in addition to its role in DNA repair this factor might participate in the protection of telomeric sequences from nuclease and ligase activities (21–23). Thus, depending on the cellular context, Ku70/80 may facilitate or prevent DNA end joining.

DSBs can be caused by a variety of exogenous and endogenous agents and are repaired either by using an intact copy of the broken DNA region as a template (homologous recombination) or by direct rejoining of the broken DNA ends (NHEJ) (20,24). Both mechanisms operate in eukaryotic cells, however, NHEJ is thought to be the predominant pathway, in particular during the G1 phase of the cell cycle (20,24). Biochemical and genetic analyses have established that at least five components are involved in the NHEJ pathway: the Ku70/80 heterodimer, DNA-PKcs, XRCC4 and DNA ligase 4 (25–28). The initial step in the NHEJ repair process requires the binding of Ku70/80 to both ends of a broken DNA molecule (18–20,29). Then Ku recruits DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs), a serine/threonine protein kinase with homology to phosphatidylinositol kinases that is activated by DNA (30). DNA-PKcs can phosphorylate itself as well as Ku and other cellular factors such as p53 (31). However, the physiologically relevant targets of this kinase remain elusive. Once bound to DNA, Ku70/80 can translocate inward from the DNA end in an ATP-independent manner, thus allowing the sequential binding of multiple Ku70/80 heterodimers to one DNA molecule. Unlike Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs is thought to remain bound to the DNA ends (32,33) and autophosphorylation has been proposed to facilitate the release of DNA-PKcs from the DNA (34). The final steps in the repair process involve the assembly on the DNA ends of a ligase4/XRCC4 complex, which is required for the ligation of the two cohesive DNA ends. The events occurring during the transition from a Ku:DNA-PKcs to a ligase4/XRCC4 complex have not been well characterized and little is known about the cellular factors involved in this process.

The observation that both WRN and DNA-PKcs are stably recruited to DNA by interactions with Ku70/80 raises the question of whether these factors assemble as a mutiprotein complex on DNA ends. In this study, to gain more insight into the relationship between WRN and the NHEJ repair machinery, we have investigated the interaction between WRN, DNA-PKcs and the Ku heterodimer. Our results show that DNA-PKcs is retained with Ku70/80 on a WRN affinity column, thus demonstrating that a trimeric complex forms in solution. Further analysis indicates that the association between DNA-PKcs and WRN occurs only in the presence of Ku70/80. In striking contrast, our experiments show that in the presence of DNA ends, the interaction of Ku70/80 with WRN and DNA-PKcs is mutually exclusive, and equimolar amounts of WRN can displace DNA-PKcs from a Ku70/80:DNA complex. The removal of DNA-PKcs from DNA-bound Ku70/80 requires the C-terminal region of WRN, which cooperates with the WRN N-terminal domain in binding to the Ku70/80 heterodimer. One consequence of this process is that DNA-PKcs cannot prevent the nucleolytic processing of DNA ends by the WRN exonuclease. Thus, the assembly on DNA of alternative complexes may be part of a regulatory process required for the repair of damaged DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein purification

DNA-PKcs was purified from 500 mg HeLa cell nuclear extracts. The nuclear extract was prepared as described previously (35) and loaded on a 30 ml fast flow DEAE–Sepharose column in buffer A (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1.0 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol and a mixture of protease inhibitors) containing 100 mM KCl. The flow-through from the DEAE–Sepharose (containing DNA-PKcs) was then incubated with a GST–Ku80(500–732) affinity resin. After extensive washes with buffer A containing 150 mM KCl, the bound Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs were eluted from the beads with buffer A containing 400 mM KCl. The eluate was dialyzed against buffer A containing 100 mM KCl and then applied to a native DNA–cellulose column. After washing the column with buffer A containing 100 mM KCl, DNA-PKcs was eluted from the column with a salt gradient in buffer A (from 250 to 350 mM). Under these conditions Ku70/80 remains bound to the resin. The purity of the purified DNA-PKcs preparation was determined by silver staining.

The C-terminal region of Ku80 used in the purification of DNA-PKcs was expressed in E.coli as a GST fusion protein [GST–Ku80(500–732)]. Escherichia coli BL21 cells were transformed with pGEX-3X-Ku80(500–732) and logarithmically growing cells were induced with 0.3 mM IPTG for 2.5 h at 30°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% Triton X-100 and a mixture of protease inhibitors, sonicated and centrifuged at 15 000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The bacterial lysate was incubated with 5 ml of glutathione–Sepharose slurry (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times in PBS with 1% Triton X-100, followed by washes in buffer A with 150 mM KCl. GST–Ku80 affinity resin was used for the purification of DNA-PKcs.

Baculoviruses expressing Flag-tagged wild-type or mutant WRN protein were used to infect Sf9 cells. Whole cells lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitors) and proteins were purified by DEAE–cellulose column and affinity chromatography on anti-Flag resin as described (17,36). GST–WRN(1–50) and GST–WRN(1306–1432) were generated by insertion of the appropriate cDNA sequences into pGEX-2T vector (Pharmacia) and expressed in E.coli. GST fusion proteins were purified on glutathione affinity resin. Histidine-tagged Ku70 and Ku80 were co-expressed in Sf9 cells and the heterodimer was purified on metal affinity resin (Talon, Clontech Biotech) and by DNA–cellulose chromatography (17).

Protein binding assay

Protein binding assays were performed as described (17,36). Flag–WRN and Flag–HCV polymerase were expressed using a baculovirus expression system. Flag–WRN and Flag–HCV polymerase were first immobilized on anti-Flag resins and then the beads were incubated with nuclear extracts from HeLa cells. Bound proteins were eluted from the resins with BCO buffer (1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors and visualized by silver staining. Bound proteins were also resolved by 5% SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Western blotting was performed using rabbit anti-DNA-PKcs antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). In similar assays, Flag–WRN immobilized on anti-Flag beads was incubated with purified DNA-PKcs or Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs. After extensive washes, the bound proteins were eluted as described above and analyzed by silver staining and immunoblotting. For GST pull-down assays GST–WRN deletion mutants were first immobilized on glutathione beads and then incubated with 500 µl of cell lysate from Sf9 cells expressing Ku70 and/or Ku80. After extensive washing, bound proteins were eluted with high salt buffer (1.0 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 10% glycerol) and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting with anti-Ku70 or anti-Ku80 antibodies.

Exonuclease assay

DNA exonuclease activity was measured as described (17,36). The 30mer oligomer 5′-CGCGCCGATTTCCCGCTAGC AATATTGTGC-3′, partially complementary to the 46mer 5′-GCGCGGAAGCTTGGCTGCAGAATATTGCTAGCGG GAAATCGGCGCG-3′, was labeled at the 5′ end with [32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. The 30mer and 46mer oligonucleotides were annealed by boiling and slow cooling to room temperature. Exonuclease reaction mixtures contained 40 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 4 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM ATP, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum protein, 40 fmol (100 000 c.p.m.) DNA substrate and 100 fmol Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and/or WRN in a final volume of 10 µl. The DNA was incubated with Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs for 10 min at room temperature, then WRN was added to the reaction mixture and the incubation was continued for an additional 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 2 µl of a formamide solution. After incubation at 95°C for 3 min, the products were resolved on a 14% polyacrylamide–urea gel and visualized by autoradiography.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

A 40/46mer DNA substrate was prepared from a 40mer oligomer (5′-CGCGCCGATTTCCCGCTAGCAATATTGTGCAGCCAAGCTT-3′, partially complementary to a 46mer oligomer, 5′-GCGCGGAAGCTTGGCTGCAGAATATTGC TAGCGGGAAATCGGCGCG-3′).

The DNA duplex (80 fmol, 200 000 c.p.m.) was incubated with 200 fmol Ku70/80 and wild-type or mutant WRN in 15 µl of buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 80 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA and 10% glycerol) at 25°C for 10 min. In the displacement reactions, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs were first incubated with the 40/46mer DNA substrate for 10 min at room temperature, then 200 fmol wild-type or mutant WRN was added to this reaction and incubated for an additional 5 min at room temperature. The samples were resolved by electrophoresis at 10 V/cm through a 4% polyacrylamide gel at 8°C. The gels were dried on Whatman 3MM paper and subjected to autoradiography.

In vitro kinase assay

Bacterially expressed GST–p53 was bound to glutathione beads and then incubated with either 200 pmol purified DNA-PKcs, 100 µg HeLa cell nuclear extract or buffer alone (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol and 1 mM ATP) in the presence of 20 µCi [32P]ATP and 100 pmol double-stranded oligonucleotide at room temperature for 30 min. The beads were washed four times with buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and the bound proteins were released by boiling the beads in SDS–PAGE sample buffer. The products were resolved on 8% polyacrylamide denaturing gels and visualized by autoradiography.

Interaction assay on streptavidin-immobilized DNA

A 39/39mer DNA duplex (100 pmol in 300 µl of H2O) biotinylated on one 5′ end was incubated with 30 µl of streptavidin–Sepharose 4B for 1 h at 4°C. After extensive washes with buffer A containing 150 mM KCl, the streptavidin-bound DNA was incubated with 1 µg purified Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs for 1 h at 4°C. The unbound proteins were washed off with buffer A containing 150 mM KCl and half of the reaction mixture was incubated with 0.5 µg full-length WRN, while the other half was incubated with 0.5 µg mutant WRN(1–749). Each reaction mixture was incubated at 4°C for 30 min and the beads were then washed with buffer A containing 150 mM KCl. The bound proteins were released by boiling in buffer containing SDS and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-DNA-PKcs antibody.

RESULTS

WRN and DNA-PKcs form a complex with Ku in the absence of DNA

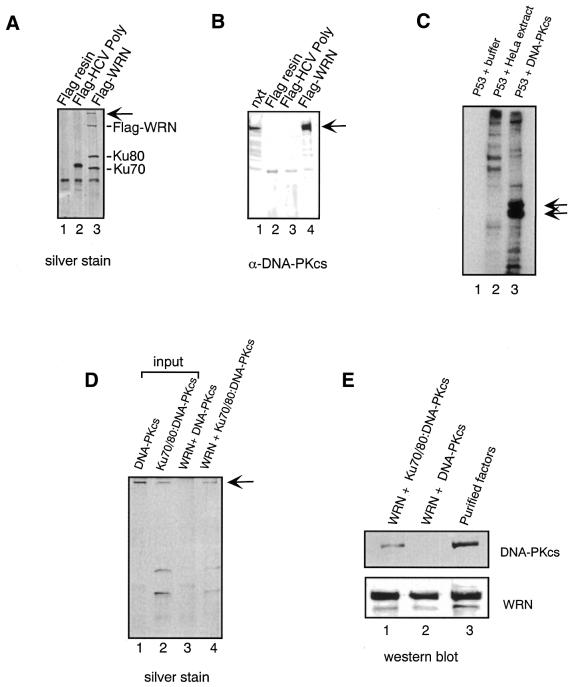

To determine whether WRN binds to DNA-PKcs, a nuclear extract from HeLa cells was incubated with Flag–WRN immobilized on anti-Flag resin and after extensive washes the bound proteins were eluted for subsequent analysis. In parallel reactions, Flag–HCV polymerase immobilized on Flag beads and anti-Flag only beads were used as control columns for the non-specific binding of proteins to the matrix. Silver staining of SDS–PAGE gels revealed that three proteins were selectively bound to the Flag-tagged WRN resin (Fig. 1A, lane 3) and not to the control resins (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 2). The two proteins, of ∼65 and 90 kDa, were previously identified as Ku70 and Ku80. The additional band on the gel was a protein whose high molecular weight was suggestive of DNA-PKcs, a relatively large polypeptide of ∼420 kDa. To establish the identity of this protein we performed immunoblot analysis using antibodies against DNA-PKcs. The antibody reacted with the high molecular weight protein eluted from the Flag–WRN resin (Fig. 1B, lane 4) but not with the eluates from the control resins (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 3), indicating that the protein corresponds to DNA-PKcs. Identical results were obtained when the nuclear extract was treated with DNase I before being loaded on the affinity column (data not shown). Next, to determine whether the association between WRN and DNA-PKcs is direct or requires the Ku heterodimer, Flag-tagged WRN was immobilized on affinity beads and incubated with either purified DNA-PKcs or a mixture of Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs. The DNA-PKcs used in this and the following assays was purified from HeLa cells and is functionally active, as indicated by its ability to phosphorylate p53 in the presence of DNA in vitro (Fig. 1C). After extensive washes, the bound proteins were eluted from the beads and analyzed by silver staining. As shown in Figure 1D, DNA-PKcs is retained on the Flag–WRN resin only in the presence of Ku70/80, suggesting that Ku70/80 is required to facilitate the interaction between WRN and DNA-PKcs. The finding that the binding of DNA-PKcs to WRN requires Ku70/80 was confirmed in a similar pull-down experiment by immunoblot analysis of the resin-bound material (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

WRN interacts with DNA-PKcs in the presence of Ku. (A) WRN-binding proteins from HeLa nuclear extracts. Flag–WRN (lane 3) and Flag–HCV polymerase (HCV-pol, lane 2) were immobilized on anti-Flag beads and incubated with nuclear extracts from HeLa cells. After extensive washes, the bound proteins were eluted from the beads with BCO buffer (1.0 M KCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol). The eluted proteins were separated on an 8% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by silver staining. The arrow indicates high molecular weight protein. (B) Identification of the >350 kDa polypeptide by western blot analysis. The proteins eluted from the anti-Flag resins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Western blot analysis was performed using antibodies against DNA-PKcs. The arrow indicates DNA-PKcs. (C) Purified DNA-PKcs phosphorylates p53. Bacterially expressed GST–p53 was bound to glutathione beads and then the beads were incubated with buffer alone (lane 1), nuclear extract from HeLa cells (lane 2) or purified DNA-PKcs (lane 3) in the presence of DNA. The beads were then washed and the bound phosphorylated proteins were analyzed by 8% SDS–PAGE followed by autoradiography (lane 1, 200 µl of kinase reaction buffer; lane 2, 100 µg nuclear extract from HeLa cells; lane 3, 200 pmol purified DNA-PKcs). The arrows indicate GST–p53. (D) Ku70/80 mediates the interaction between WRN and DNA-PKcs. Equal amounts of purified DNA-PKcs (lanes 1 and 3) and Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs (lanes 2 and 4) were incubated with Flag–WRN immobilized on anti-Flag beads (lanes 3 and 4) and the bound proteins were then eluted and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and silver staining. The arrow indicates DNA-PKcs. (E) Reactions were performed as in (D) and the resin-bound proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-DNA-PKcs (top) and anti-WRN (bottom) antibody. Lane 1, Flag–WRN + Ku70/80 + DNA-PKcs; lane 2, Flag–WRN + DNA-PKcs; lane 3, purified DNA-PKcs (top) or WRN (bottom).

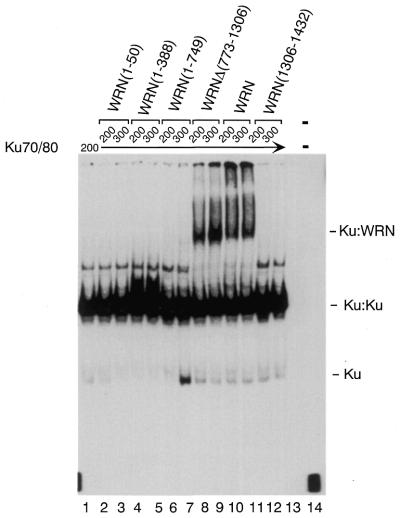

Both the N- and C-terminal regions of WRN are required to form a stable complex with Ku70/80:DNA

Our earlier work demonstrated that the Ku70/80 heterodimer is required for the recruitment of WRN to the DNA substrate (36). To examine in more detail which domain of WRN is required for the formation of a stable WRN:Ku70/80 complex on DNA, we analyzed the behavior of full-length WRN and a series of WRN deletion mutants in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). The incubation of a 40/46mer DNA with Ku70/80 leads to the formation of two complexes, which correspond to one or two Ku heterodimers bound to DNA (Fig. 2, lane 1) (36). Upon addition of full-length WRN an additional slower migrating band appeared in the gel (lanes 10 and 11), which we previously identified as the WRN:Ku70/80:DNA complex (36). A similar pattern of shifted bands is observed in the presence of the deletion mutant WRNΔ(773–1306) (lanes 8 and 9), suggesting that the region of WRN between amino acids 773 and 1306 is not required for the recruitment of WRN to DNA by Ku70/80. On the other hand, the WRN mutants missing either the C-terminus [WRN(1–50), WRN(1–388) and WRN(1–749)] or the N-terminus [WRN(1306–1432)] failed to form a stable complex with Ku70/80 on DNA, evident by the absence of a specific shifted complex (lanes 2–7, 12 and 13). These results suggest that the N- and C-terminal domains of WRN are both required for the formation of a stable complex with Ku on DNA.

Figure 2.

The N- and C-terminal regions of WRN are required for the formation of a stable complex with Ku70/80 on DNA. Radiolabeled 40/46mer DNA and purified Ku70/80 and WRN or WRN fragments were first incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The reactions were analyzed by 4% native PAGE and the DNA–protein complexes were visualized by autoradiography. Femtomoles of Ku70/80 and WRN used in each reaction are indicated at the top of the gel. Lane 1, 200 fmol Ku70/80; lane 2, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 200 fmol GST–WRN(1–50); lane 3, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 300 fmol GST–WRN(1–50); lane 4, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 200 fmol Flag–WRN(1–388); lane 5, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 300 fmol Flag–WRN(1–388); lane 6, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 200 fmol Flag–WRN(1–749); lane 7, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 300 fmol Flag–WRN(1–749); lane 8, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 200 fmol Flag–WRNΔ(773–1306); lane 9, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 300 fmol Flag–WRNΔ(773–1306); lane 10, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 200 fmol Flag–WRN; lane 11, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 300 fmol Flag–WRN; lane 12, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 200 fmol GST–WRN(1306–1432); lane 13, 200 fmol Ku70/80 and 300 fmol GST–WRN(1306–1432); lane 14, DNA probe only.

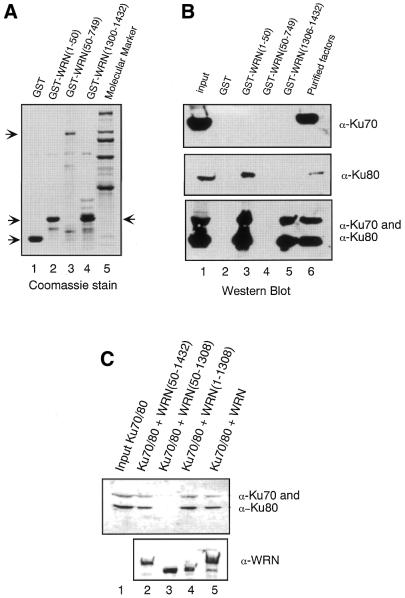

The C-terminal region of WRN binds to the Ku70/80 complex, but not to individual Ku subunits

We have previously shown that WRN binds to Ku80 but not to Ku70 and that the interaction between WRN and Ku80 is mediated by the N-terminus of WRN (17). Because the EMSA indicated that the C-terminal domain of WRN is also required to recruit this factor to DNA, we then asked whether this region of WRN might interact with the Ku70/80 heterodimer. For this purpose, GST fusion proteins containing the N-terminus [GST–WRN(1–50)], central domain [GST–WRN(50–749)] or C-terminus [GST–WRN(1306–1432)] of WRN (Fig. 3A) were immobilized on glutathione beads and then incubated with extracts from Sf9 cells expressing individual subunits or the Ku70/80 heterodimer. After extensive washes, the bound proteins were resolved on a SDS–PAGE gel and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Ku70 and Ku80. In agreement with our previous data, Ku70 did not bind to any of the WRN mutants (Fig. 3B, top), while the first 50 amino acids of WRN [GST–WRN(1–50)] were sufficient to bind to Ku80 (Fig. 3B, middle, lane 3). The N-terminus of WRN also bound to the Ku70/80 heterodimer (Fig. 3B, bottom, lane 3). Interestingly, the C-terminal region of WRN [GST–WRN(1306–1432)], which did not associate with individual Ku subunits, bound to the Ku70/80 heterodimer (Fig. 3B, bottom, lane 5). To substantiate the association between Ku70/80 and WRN N- and C-terminal regions, WRN mutants missing the N-terminus [WRN(50–1432)], the C-terminus [WRN(1–1308)] or both [WRN(50–1308)] regions were used in protein binding assays. As shown in Figure 3C, Ku70/80 bound to WRN(50–1432) and WRN(1–1308) but not to WRN(50–1308), confirming that the N-terminus (amino acids 1–50) and C-terminus (amino acids 1308–1432) of WRN make direct contacts with Ku70/80. Taken together with the results of the EMSA (Fig. 2), these data suggest that the stable recruitment of WRN to DNA requires simultaneous interaction of the WRN N- and C-terminal regions with the Ku heterodimer.

Figure 3.

The C-terminal region of WRN binds to Ku70/80. (A) The Coomassie stained gel shows an aliquot of the GST fusion proteins that were used in the protein interaction studies. Lane 1, GST; lane 2, GST– WRN(1–50); lane 3, GST–WRN(50–749); lane 4, GST–WRN(1306–1432); lane 5, molecular markers. The arrows indicate the positions of the GST fusion proteins on the stained gel. (B) A sample of 4 µg of each GST fusion protein was immobilized on glutathione beads and incubated with 500 µl of cell lysates from Sf9 cells expressing Ku70 (top), Ku80 (middle) or Ku70/80 (bottom). After extensive washes, bound proteins were analyzed by western blotting with anti-Ku70 (top), anti-Ku80 (middle) and a mixture of anti-Ku70 and anti-Ku80 (bottom) antibodies. The input lane (lane 1) shows 5% of Ku70 (top), Ku80 (middle) and Ku70/80 (bottom) used in each pull-down assay. Lane 1, input protein extract; lane 2, GST; lane 3, GST–WRN(1–50); lane 4, GST–WRN(50–749); lane 5, GST–WRN(1306– 1432); lane 6, purified factor (Ku70, top; Ku80, middle; Ku70/80, bottom). (C) Flag-tagged WRN(50–1432) (lane 2), WRN(50–1308) (lane 3), WRN(1–1308) (lane 4) and full-length WRN (lane 5) were immobilized on beads and incubated with extracts from Sf9 cells overexpressing Ku70/80. After extensive washes, the bound proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and analyzed with a mixture of anti-Ku70 and anti-Ku80 antibodies (top) and WRN antibody (bottom). Lane 1 represents 5% of the Ku70/80 extract used in each reaction.

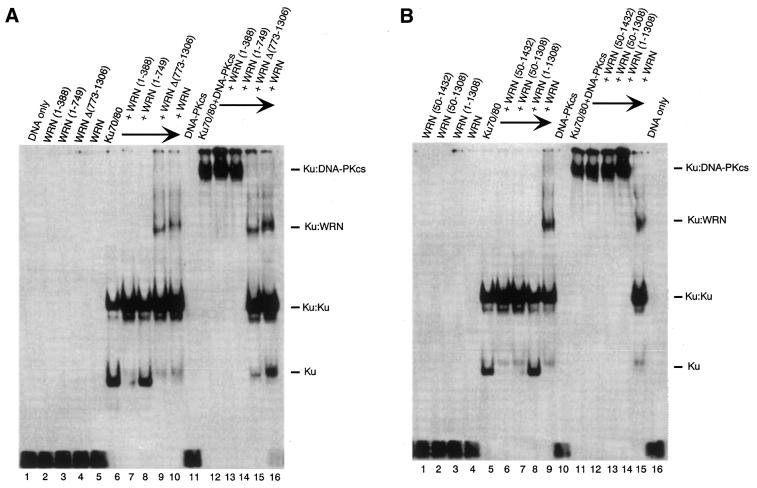

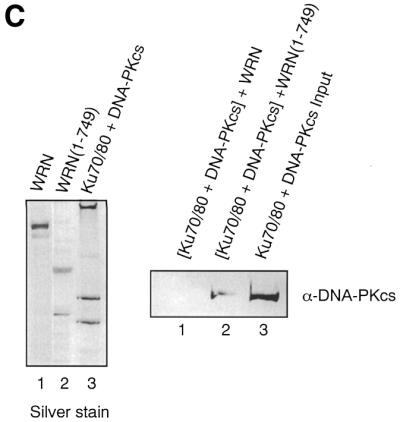

WRN displaces DNA-PKcs from the Ku70/80:DNA complex

Studies from several laboratories have indicated that Ku70/80 recruits DNA-PKcs to DNA ends. This process leads to the activation of DNA-PKcs kinase activity, probably as the result of conformational changes in DNA-PKcs upon binding to the Ku70/80:DNA complex (37). Because our results indicate that Ku70/80 recruits WRN to the ends of DNA (36) we wished to determine whether WRN could bind to a DNA-PKcs:Ku70/80 complex on DNA. For this purpose, full-length WRN and a series of WRN deletion mutants were tested in gel shift assays in combination with Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs. As shown in Figure 4, neither the wild-type nor any of the WRN mutants used in this experiment formed a stable complex with DNA (Fig. 4A, lanes 2–5, Fig. 4B, lanes 1–4). As expected, the addition of Ku 70/80 to DNA leads to the formation of two retarded DNA bands (Fig. 4A, lane 6, Fig. 4B, lane 5). A third retarded DNA band is formed upon the addition of WRN or WRNΔ(773–1306) (Fig. 4A, lanes 9–10, Fig. 4B, lane 9), which corresponds to a Ku70/80:WRN:DNA complex (36). DNA-PKcs does not bind to DNA by itself (Fig. 4A, lane 11, Fig. 4B, lane 10), but it forms a distinct high molecular weight complex in the presence of Ku70/80 (Fig. 4A, lane 12, Fig. 4B, lane 11). Interestingly, the addition of stoichiometric amounts of wild-type WRN or WRNΔ(773–1306) to a preformed Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs complex resulted in the disappearance of the slower migrating band (Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs:DNA) and the formation of a new complex with the same electrophoretic mobility as the Ku70/80:WRN:DNA complex (Fig. 4A, lanes 15 and 16). This process was strictly dependent on the presence of a WRN protein having both Ku-binding domains, since none of the WRN mutants missing either the N-terminus [WRN(50–1432), Fig. 4B, lane 12], the C-terminus [WRN(1–388), Fig. 4A, lane 13; WRN(1–749), Fig. 4A, lane 14; WRN(1–1308), Fig. 4B, lane 14] or both domains [WRN(50–1432), Fig. 4B, lane 13] displaced DNA-PKcs from the Ku70/80:DNA complex. These results suggest that the WRN:DNA-PKcs:Ku complex does not form on DNA. Furthermore, they indicate that the Ku interaction domains located in the N- and C-terminal regions of WRN are required to dissociate DNA-PKcs from DNA. To provide further evidence that WRN removes DNA-PKcs from a Ku70/80:DNA complex, we performed protein binding assays on immobilized DNA templates. Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs were loaded onto biotinylated DNA that was immobilized on streptavidin beads and then incubated with either full-length WRN or a mutant WRN missing the C-terminal region [WRN(1–748)]. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 4°C and the unbound material was removed by extensive washes. Then the bound proteins were released from the beads and analyzed by immunoblotting with DNA-PKcs antibody. As shown in Figure 4C, the addition of wild-type WRN (lane 1) led to the disappearance of DNA-PKcs from the DNA-bound material, indicating that WRN displaces DNA-PKcs from the Ku70/80:DNA complex. Moreover, the inability of the mutant WRN(1–749) (lane 2) to perform this function demonstrates that both Ku-binding domains of WRN are required in the process.

Figure 4.

WRN displaces DNA-PKcs from a DNA:Ku70/80 complex. (A) Gel retardation assays were conducted with a radiolabeled 40/46mer DNA substrate and purified Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and wild-type or mutant WRN. The DNA substrate was first incubated with 200 fmol Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs at room temperature for 10 min, then 200 fmol wild-type or mutant WRN was added to the reactions and the incubation was continued for an additional 5 min at room temperature. The reaction mixture was subjected to 4% native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at 8°C. Shifted bands were visualized by autoradiography. Lane 1, DNA only; lane 2, WRN(1–388); lane 3, WRN(1–749); lane 4, WRNΔ(773–1306); lane 5, WRN; lane 6, Ku70/80; lane 7, Ku70/80 and WRN(1–388); lane 8, Ku70/80 and WRN(1–749); lane 9, Ku70/80 and WRNΔ(773–1306); lane 10, Ku70/80 and WRN; lane 11, DNA-PKcs; lane 12, Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs; lane 13, Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN(1–388); lane 14, Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN(1–749); lane 15, Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRNΔ(773–1306); lane 16, Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN. (B) Gel retardation assays were performed as described in (A). Lane 1, WRN(50–1432); lane 2, WRN(50–1308); lane 3, WRN(1–1308); lane 4, WRN; lane 5, Ku70/80; lane 6, Ku70/80 and WRN(50–1432); lane 7, Ku70/80 and WRN(50–1308); lane 8, Ku70/80 and WRN(1–1308), lane 9, Ku70/80 and WRN; lane 10, DNA-PKcs, lane 11, Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs; lane 12, Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN(50–1432); lane 13, Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN(50–1308); lane 14, Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN(1–1308); lane 15, Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN; lane 16, DNA alone. (C) WRN removes DNA-PKcs from a Ku70/80:DNA complex. (Left) Silver stained gel showing the proteins used in the assay. Lane 1, WRN; lane 2, WRN(1–749); lane 3, Ku70/80 + DNA-PKcs. (Right) Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs were bound to a 5′ end-biotinylated 39/39 double-stranded oligomer immobilized on streptavidin beads and then incubated with 150 µl of a solution containing WRN (lane 1) or mutant WRN(1–749) (lane 2). The mixture was incubated at 4°C for 30 min, after which the beads were washed extensively and the bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting using DNA-PKcs antibody. Lane 3 shows purified DNA-PKcs as a positive control.

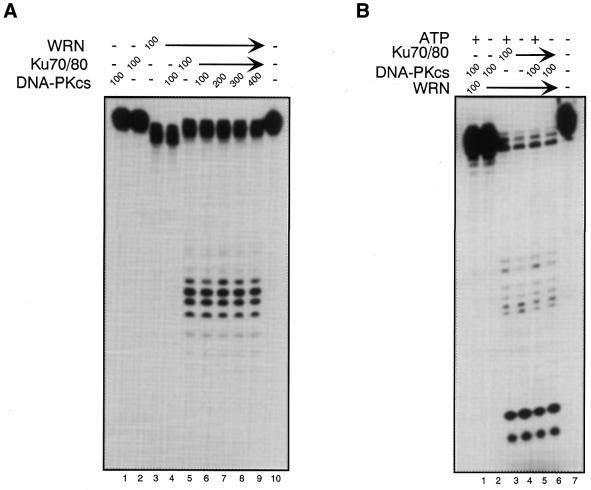

DNA-PKcs does not protect DNA from nucleolytic processing by WRN

It has been proposed that the binding of DNA-PKcs to DNA ends might protect DNA from degradation by cellular nucleases. The finding that DNA-PKcs is displaced from the DNA ends by WRN suggests that WRN exonuclease activity may not be influenced by the presence of DNA-PKcs. To test this hypothesis, we performed a WRN exonuclease assay in the presence of purified Ku70/80 and DNA-PKcs (Fig. 5). As shown previously (17), WRN nucleolytic activity was strongly stimulated by Ku70/80 (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 3 and 5). In the absence of Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs did not influence WRN exonuclease activity (Fig. 5A, lane 4), either in the presence or absence of ATP (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 1 and 2). Likewise, the strong stimulation of WRN exonuclease activity by Ku70/80 is not affected by the addition of DNA-PKcs (Fig. 5A, lanes 6–9), also in the presence of ATP (Fig. 5B, lane 6). Taken together, these results indicate that DNA-PKcs does not protect the DNA termini from nucleolytic degradation by the WRN exonuclease.

Figure 5.

DNA-PKcs does not protect DNA from the exonuclease activity of WRN. (A) Ku70/80 (100 fmol) and DNA-PKcs (100–400 fmol) were incubated with radiolabeled 30/46mer DNA substrate at room temperature for 10 min. WRN (100 fmol) was added to this reaction and incubated for an additional 10 min. The reaction products were analyzed by 14% polyacrylamide–urea denaturing gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Femtomoles of Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN are indicated at the top of the gel. Lane 1, 100 fmol DNA-PKcs; lane 2, 100 fmol Ku70/80; lane 3, 100 fmol WRN; lane 4, 100 fmol WRN and DNA-PKcs; lane 5, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80; lane 6, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs; lane 7, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80 and 200 fmol DNA-PKcs; lane 8, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80 and 300 fmol DNA-PKcs; lane 9, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80 and 400 fmol DNA-PKcs; lane 10, probe only. (B) Exonuclease activity of WRN:DNA-PK in the presence or absence of ATP. Reactions were performed as described in (A) and incubated at room temperature for an additional 15 min after the addition of WRN. Femtomoles of Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs and WRN are indicated at the top of the gel. Lane 1, 100 fmol WRN and DNA-PKcs in the presence of ATP; lane 2, 100 fmol WRN and DNA-PKcs in the absence of ATP; lane 3, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80 in the presence of ATP; lane 4, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80 in the absence of ATP; lane 5, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs in the presence of ATP; lane 6, 100 fmol WRN and Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs in the absence of ATP; lane 7, probe only.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have examined the relationship between WRN and two components of the NHEJ repair pathway, Ku and DNA-PKcs. Our analysis indicates that in the absence of DNA WRN assembles into a triple complex with Ku and DNA-PKcs. The association between WRN and DNA-PKcs requires the presence of Ku, suggesting that the binding of WRN to DNA-PKcs is probably not direct, but rather is mediated by the Ku70/80 heterodimer. To determine whether DNA influences the molecular interactions between these factors we performed gel shift assays with purified components. The results of these experiments indicate that a WRN:Ku:DNA-PKcs complex does not form on DNA and equimolar amounts of WRN can displace DNA-PKcs from a preformed complex with Ku70/80 on DNA. By titrating increasing amounts of DNA-PKcs we have observed the formation of distinct WRN:Ku70/80:DNA and DNA-PKcs:Ku70/80:DNA complexes in the same reaction mixture, but we have not detected a supershifted band suggestive of a WRN:Ku70/80:DNA-PKcs:DNA complex (data not shown). Importantly, our data show that the displacement of DNA-PKcs from DNA by WRN requires both the N- and the C-terminal domains of WRN, each of which makes direct contacts with Ku70/80. The finding that the WRN C-terminus, in addition to the N-terminus, binds to Ku70/80 is in agreement with the data from another laboratory, which identified the Ku heterodimer as a WRN-interacting factor through an affinity screen that used the C-terminal region of WRN as bait (16). Our analysis further indicates that while the N- and C-terminal regions of WRN can interact with Ku in solution independently of each other, both domains are required for the formation of a stable WRN:Ku complex on DNA and for displacing DNA-PKcs from the Ku:DNA complex. It is possible that the displacement of DNA-PKcs from the Ku70/80:DNA complex may be facilitated by specific conformational changes in DNA-PKcs that occur upon recruitment of this factor to the DNA ends and activation of its kinase activity.

This work and two other recent studies on the interaction between DNA-PKcs and WRN differ in some of their conclusions (38,39). One study suggests that the interaction between WRN and DNA-PKcs is direct (39), while the other indicates, as we have shown in this report, that Ku70/80 is required for the binding of WRN to DNA-PKcs (38). Furthermore, both papers suggest that WRN and DNA-PKcs can concurrently form a complex with Ku70/80 on DNA. However, the functional significance of these molecular interactions is not consistent between the two studies: while the results from one group indicate that DNA-PKcs represses WRN exonuclease activity only in the presence of Ku70/80 (38), the other shows that WRN exonuclease activity is inhibited only in the absence of Ku70/80 (39). We cannot provide a likely explanation for these differences, but it is possible that the quality of protein preparations and/or minor variation in the experimental procedures may be responsible for these effects. Using different preparations of highly active, Ku70/80-free DNA-PKcs, we have not detected either a direct interaction between WRN and DNA-PKcs or a significant inhibition of WRN exonuclease activity, even in the presence of excess DNA-PKcs. It is possible that the WRN:DNA-PKcs:Ku70/80 complex shown in the other reports may be due to the presence of glutaraldehyde in the gel shift assays, since most of these assays were performed with a reaction mixture treated with the cross-linking reagent prior to electrophoresis (38,39). We have performed gel shift assays in the presence of glutaraldehyede (data not shown), however, the results of these experiments were not highly reproducible and therefore not easily interpretable.

Our data suggest one of two models for how WRN could function to maintain genetic stability. First, since one of the known functions of Ku and DNA-PKcs is in the repair of DNA damage by NHEJ, WRN could be directly participating in the NHEJ repair process by releasing DNA-PKcs from the DNA ends prior to the ligation step. Indeed, several studies have suggested that while the Ku70/80 heterodimer translocates inward, DNA-PKcs remains bound to the DNA ends (32,33,37). The subsequent steps in the NHEJ repair pathway require recruitment of the XRCC4:ligase IV complex, which catalyzes rejoining of the broken DNA ends. It is likely that in order to allow proper DNA ligation, DNA-PKcs needs to be released from the DNA ends. Our results suggest that WRN may be part of this release mechanism during progression of the repair process.

As an alternative model, it is possible that by preventing the stable association of DNA-PKcs with DNA-bound Ku, WRN inhibits the functional assembly of the NHEJ repair complex and contributes to the implementation of an alternative pathway. Such a pathway could be triggered by DNA damage caused by genotoxins such as 4 nitroquinoline-1-oxide and camptothecin, two chemical agents to which WRN cells are extremely sensitive, and may require the coordinate action of Ku and WRN but not DNA-PKcs. Thus, WRN and Ku may function in a novel pathway to maintain genomic stability.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the M.E. Early Trust Research Fund to L.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goto M., Miller,R.W., Ishikawa,Y. and Sugano,H. (1996) Excess of rare cancers in Werner’s Syndrome (adult progeria). Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 5, 239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyer C. and Sinclair,A. (1998) The premature ageing syndromes: insights into the ageing process. Age Ageing, 27, 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein C.J., Martin,G.M., Schultz,A.L. and Motulsky,A.G. (1966) Werner’s syndrome. A review of its symptomatology, natural history, phatological features, genetics and relationship to the natural aging process. Medicine, 45, 177–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salk D., Au,K., Hoehn,H. and Martin,G.M. (1985) Cytogenetic aspects of Werner syndrome. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol., 190, 541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuchi K., Martin,G.M. and Monnat,R.J. (1989) Mutator phenotype of Werner syndrome is characterized by extensive deletions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 5893–5897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebhart E., Bauer,R., Raub,U., Schinzel,M., Ruprecht,K.W. and Jonas,J.B. (1988) Spontaneous and induced chromosomal instability in Werner syndrome. Hum. Genet., 80, 135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu C.E., Oshima,J., Fu,Y.H., Wijsman,E., Hisama,F., Alisch,R., Matthews,S., Nakura,J., Miki,T., Ouais,S., Martin,G., Mulligan,J. and Schellenberg,G. (1996) Positional cloning of the Werner’s syndrome gene. Science, 272, 258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karow J.K., Wu,L. and Hickson,I.D. (2000) RecQ family helicases: roles in cancer and aging. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 10, 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser M.J., Holley,W.R., Chatterjee,A. and Mian,I.S. (1997) The proofreading domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I and other DNA and/or RNA exonuclease domains. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 5110–5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray M., Shen,J.C., Kamath-Loeb,A., Blank,A., Sopher,B., Martin,G., Oshima,J. and Loeb,L. (1997) The Werner syndrome protein is a DNA helicase. Nature Genet., 17, 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki N., Shimamoto,A., Imamura,O., Kuromitsu,J., Kitao,S., Goto,M. and Furuichi,Y. (1997) DNA helicase activity in Werner’s syndrome gene product synthesized in a baculovirus system. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2973–2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen J.C., Gray,M., Oshima,J. and Loeb,L. (1998) Characterization of Werner syndrome protein DNA helicase activity: directionality, substrate dependence and stimulation by replication protein A. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 2879–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen J.C., Gray,M., Oshima,J., Kamath-Loeb,A., Fry,M. and Loeb,L. (1998) Werner syndrome protein: I. DNA helicase and DNA exonuclease reside on the same polypeptide. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 34139–34144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamath-Loeb A., Shen,J.C., Loeb,L. and Fry,M. (1998) Werner syndrome protein: II. Characterization of the integral 3′→5′ DNA exonuclease. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 34145–34150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang S., Li,B., Gray,M., Oshima,J., Mian,I.S. and Campisi,J. (1998) The premature ageing syndrome protein, WRN, is a 3′→5′ exonuclease. Nature Genet., 20, 114–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper M.P., Machwe,A., Orren,D.K., Brosh,R.M., Ramsden,D. and Bohr,V.A. (2000) Ku complex interacts with and stimulates the Werner protein. Genes Dev., 14, 907–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B. and Comai,L. (2000) Functional interaction between Ku and the Werner syndrome protein in DNA end processing. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 28349–28352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanaar R., Hoeijmakers,J. and van Gent,D.C. (1998) Molecular mechanisms of DNA double-strand break repair. Cell Biol., 8, 483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieber M. (1998) Pathological and physiological double-strand breaks: roles in cancer, aging, and the immune system. Am. J. Pathol., 153, 1323–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karran P. (2000) DNA double strand break repair in mammalian cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 10, 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey S.M., Meyne,J., Chen,D.J., Kurimasa,A., Li,G.C., Lehnert,B.E. and Goodwin,E.H. (1999) DNA double-strand break repair proteins are required to cap the ends of mammalian chromosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14899–14904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu H.L., Gilley,D., Blackburn,E. and Chen,D. (1999) Ku is associated with the telomere in mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 12454–12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu H.L., Gilley,D., Galande,S.A., Hande,M.P., Allen,B., Kim,S.H., Li,G.C., Campisi,J., Kohwi-Shigematsu,T. and Chen,D.J. (2000) Ku acts in a unique way at the mammalian telomere to prevent end joining. Genes Dev., 14, 2807–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haber J.E. (2000) Partners and pathways repairing a double-strand break. Trends Genet., 16, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dynan W.S. and Yoo,S. (1998) Interaction of Ku protein and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit with nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 1551–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottlieb T.M. and Jackson,S.P. (1993) The DNA-dependent protein kinase requirement for DNA ends and association with Ku antigen. Cell, 72, 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammarsten O. and Chu,G. (1998) DNA-dependent protein kinase-DNA binding and activation in the absence of ku. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grawunder U., Wilm,M., Wu,X., Kulesza,P., Wilson,T.E., Mann,M. and Lieber,M.R. (1997) Activity of DNA ligase IV stimulated by complex formation with XRCC4 protein in mammalian cells. Nature, 388, 492–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Critchlow S. and Jackson,S.P. (1998) DNA end-joining: from yeast to man. Trends Biochem. Sci., 23, 394–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartley K.O., Gell,D., Smith,G.C., Zhang,H., Divecha,N., Connelly,M.A., Admon,A., Lees-Miller,S.P., Anderson,C.W. and Jackson,S.P. (1995) DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit: a relative of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the ataxia telangiectasia gene product. Cell, 82, 849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lees-Miller S.P., Chen,Y.R. and Anderson,C.W. (1990) Human cells contain a DNA-activated protein kinase that phosphorylates simian virus 40 T antigen, mouse p53, and the human Ku autoantigen. Mol. Cell Biol., 10, 6472–6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devries E.W., Vandriel,W.C., Bergsma,A.C. and Vandervliet,P.C. (1989) HeLa nuclear protein recognizing DNA termini and translocation on DNA forming a regular DNA multimeric protein complex. J. Mol. Biol., 208, 65–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pailard S. and Strauss,F. (1991) Analysis of the mechanism of interaction of simian Ku protein with DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 5619–5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan D.W. and Lees-Miller,P. (1996) The DNA-dependent protein kinase is inactivated by autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 8936–8941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comai L., Tanese,N. and Tjian,R. (1992) The TATA-binding protein and associated factors are integral components of the RNA polymerase I transcription factor, SL1. Cell, 68, 965–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li B. and Comai,L. (2001) Requirements for the nucleoytic processing of DNA ends by the Werner syndrome protein:Ku70/80 complex. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 9896–9902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoo S. and Dynan,W.S. (1999) Geometry of a complex formed by double strand break repair proteins at a single DNA end: recruitment of DNA-PKcs induces inward translocation of Ku protein. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 4679–4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karmakar P., Piotrowski,J., Brosh,R.M.,Jr, Sommers,J.A., Miller,S.P., Cheng,W.H., Snowden,C.M., Ramsden,D.A. and Bohr,V.A. (2002) Werner protein is a target of DNA-dependent protein kinase in vivo and in vitro and its catalytic activities are regulated by phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 18291–18302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yannone S.M., Roy,S., Chan,D.W., Murphy,M.B., Huang,S., Campisi,J. and Chen,D.J. (2001) Werner syndrome protein is regulated and phosphorylated by DNA-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 38242–38248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]