Abstract

The response of eukaryotic cells to the formation of a double-strand break (DSB) in chromosomal DNA is highly conserved. One of the earliest responses to DSB formation is phosphorylation of the C-terminal tail of H2A histones located in nucleosomes near the break. Histone variant H2AX and core histone H2A are phosphorylated in mammals and budding yeast, respectively. We demonstrate the DSB-induced phosphorylation of histone variant H2Av in Drosophila melanogaster. H2Av is a member of the H2AZ family of histone variants. Ser137 within an SQ motif located near the C- terminus of H2Av was phosphorylated in response to γ-irradiation in both tissue culture cells and larvae. Phosphorylation was detected within 1 min of irradiation and detectable after only 0.3 Gy of radiation exposure. Photochemically induced DSBs, but not general oxidative damage or UV-induced nicking of DNA, caused H2Av phosphorylation, suggesting that phosphorylation is DSB specific. Imaginal disc cells from Drosophila expressing a mutant allele of H2Av with its C-terminal tail deleted, and therefore unable to be phosphorylated, were more sensitive to radiation-induced apoptosis than were wildtype controls, suggesting that phosphorylation of H2Av is important for repair of radiation-induced DSBs. These observations suggest that in addition to providing the function of an H2AZ histone, H2Av is also the functional homolog in Drosophila of H2AX.

INTRODUCTION

A double-strand break (DSB) in chromosomal DNA is a potentially lethal lesion and, if not repaired accurately, can create genetic instabilities and gene mutations that predispose a cell to neoplastic transformation. The response of eukaryotic cells to the formation of a DSB is highly conserved and involves both checkpoint functions that arrest the cell cycle, allowing time for repair to occur, and repair functions that directly fix the break (for a review see 1). DSBs can be repaired by homologous recombination (HR) or non- homologous end joining (NHEJ). Both mechanisms are used in higher eukaryotes, with NHEJ being used predominantly in G1 and HR in G2 of the cell cycle (for an example see 2; for a review see 3). HR is the predominant mechanism of repair used by yeast (3 and references therein).

One of the earliest known responses to DSB formation is phosphorylation of the C-terminal tails of H2A histones in nucleosomes located in the vicinity of the break (4,5). Histone variant H2AX is the H2A histone that is phosphorylated in mammals (6). The amino acid sequence of H2AX is nearly identical to that of H2A except for its C-terminal tail, which has a divergent sequence and 13 additional amino acids (see Fig. 1) (7). H2AX is phosphorylated on Ser139 in an SQ motif located near the C-terminus (Fig. 1) (6). The phosphorylated form of H2AX is referred to as γ-H2AX. H2AX is phosphorylated by the PIK-related protein kinase ATM or ATR, depending on whether the break is introduced by radiolytic damage or replicative stress, respectively (8,9). Phosphory lation occurs within 20 s of radiation-induced break formation, making it the earliest event known to occur after DNA breakage and kinase activation (6). While H2AX is uniformly distributed in chromatin, only H2AX located in the vicinity of a DSB becomes phosphorylated, and a single domain of phosphorylation might encompass megabases of DNA (10). DSBs also induce phosphorylation in budding yeast, but in yeast it is the core histone H2A that is phosphorylated rather than a histone variant (11). Yeast H2A is phosphorylated within an SQ motif located in its C-terminal tail, analogous to mammalian H2AX (Fig. 1) (11). This evolutionary conservation suggests that H2A phosphorylation is a conserved response of eukaryotic cells to DSBs (5).

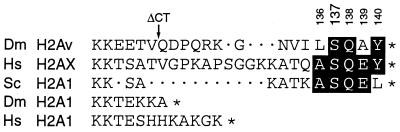

Figure 1.

C-terminal amino acid sequence of H2A histones. The C-terminal tails of H2Av and H2A1 from D.melanogaster (Dm), H2AX and H2A1 from human (Hs) and H2A1 from S.cerevisiae (Sc) are shown, starting at the conserved lysine pair located at the beginning of the C-terminal tail of these histones. Dots indicate gaps and asterisks indicate stop codons. Amino acid numbers for Dm H2Av are shown above the sequence and the position at which the ΔCT mutation truncates H2Av is indicated with an arrow. Amino acids of the conserved SQ motif are highlighted and the serine that is phosphorylated in response to a DSB in each histone is aligned below Dm H2Av Ser137.

DSB-induced phosphorylation of H2A histones is important for some mechanisms by which the DSB is repaired. In budding yeast that lack H2A phosphorylation, for example, repair by NHEJ is reduced 2-fold, and knockout mice that lack H2AX have a pleiotropic phenotype that includes increased genomic instability, increased radiation sensitivity, reduced immunoglobulin class switching, and male sterility (11,12). For some mechanisms of repair, phosphorylation of H2A histones appears to be less important, such as for homology-dependent repair in yeast and V(D)J recombination in mammals (11,12). So, even though localized phosphorylation of H2A histones has been found at all DSBs thus far studied, irrespective of how the break is formed or the pathway by which it is eventually repaired, H2A phosphorylation may be functionally important for only a subset of repair processes (6,8,11–17).

Antibodies that specifically bind phosphorylated H2AX in mammals also recognize radiation-induced proteins in Muntiacus muntjac, Xenopus laevis and Drosophila melanogaster (10). The fruitfly, D.melanogaster, has a single H2A variant, H2Av, in addition to core histone H2A (18). H2Av is an essential gene and is homologous to the H2AZ family of histone variants, which function in the chromatin-mediated regulation of transcription (19–22). In addition to H2Av being the H2AZ ortholog of flies, the C-terminal tail of H2Av also contains an SQ motif similar to that in mammalian H2AX and yeast H2A (see Fig. 1; for a broader phylogenetic comparison see also 5). The presence of the SQ motif prompted previous investigators to predict that H2Av would be the protein in Drosophila recognized by γ-H2AX-specific antibodies (10). We tested this prediction and, in this report, we demonstrate that the C-terminal tail of Drosophila H2Av is phosphorylated in response to radiation-induced DSBs, specifically at Ser137 within the SQ motif. Furthermore, mutant animals that lack H2Av phosphorylation have increased levels of radiation-induced apoptosis of imaginal disc cells, although the increase in apoptosis caused little or no larval lethality. These results suggest a function for H2Av phosphorylation in repair of radiation-induced DSBs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibody synthesis and affinity purification

A polyclonal antiserum that recognizes both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated H2Av was generated by injecting rabbits with a synthetic peptide homologous to the C-terminal 15 amino acids of H2Av in which Ser137 was phosphorylated. All procedures were approved by the Wadsworth Center IACUC committee. The peptide was conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin via an added N-terminal cysteine before injection (Imject Maleimide Activated KLH Kit; Pierce). This antiserum was used for all experiments except for the experiment illustrated in Figure 2B, in which phosphorylation- specific antibodies were used. Antibodies that bound only phosphorylated H2Av peptide were isolated by reverse affinity purification. A peptide identical to the C-terminal 15 amino acids of H2Av but lacking a phosphate on Ser137 was coupled to beaded agarose via an added N-terminal cysteine (Sulfolink Kit; Pierce). Serum antibodies that bound non-phosphorylated peptide were then removed by column chromatography and antibodies specific for phosphorylated H2Av were collected in the flow-through.

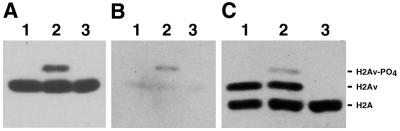

Figure 2.

Radiation-induced phosphorylation of H2Av on Ser137. (A) Histones were isolated from S2 cells that were untreated (lane 1), were exposed to 50 Gy of γ-radiation (lane 2) or were exposed to 50 Gy of γ-radiation followed by treatment with alkaline phosphatase after histone isolation (lane 3). H2Av was visualized by western blotting using unpurified antiserum against the H2Av phosphopeptide. (B) The western blot illustrated in (A) was stripped and reprobed with affinity-purified antibodies that specifically recognize H2Av phosphorylated on Ser137. (C) Histones were isolated from whole larvae of genotype P{His2AvΔCT};l(3)His2Av810/TM6B, which express wildtype H2Av from the TM6B chromosome, untreated (lane 1) or exposed to 40 Gy of γ-radiation (lane 2). Histones were isolated from larvae of genotype P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810, which express only the ΔCT allele of H2Av, exposed to 40 Gy of γ-radiation (lane 3). H2Av was visualized by western blotting using unpurified antiserum against the H2Av phosphopeptide. Antiserum specific for H2A was added to the analysis as a loading control (26).

Drosophila strains and tissue culture cells

Information about Drosophila genes and nomenclature may be found at Flybase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu). Flies were maintained at 23°C and 55% relative humidity on cornmeal– brewer’s yeast–glucose medium. Strains P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810/TM6B, P{His2AvΔCTXa};l(3)His2Av810/TM6B and P{His2AvWTXa};l(3)His2Av810/TM6B were originally constructed to analyze the essential function of H2Av as the Drosophila H2AZ homolog (23). The transgene is inserted on the X chromosome in each strain. Tb+ larvae that are P{His2Av};l(3)His2Av810/l(3)His2Av810 and lack expression of the endogenous His2Av gene and Tb– larvae that are P{His2Av};l(3)His2Av810/TM6B and have a wildtype His2Av gene on the TM6B chromosome were collected from each strain as needed for specific experiments. Drosophila S2 tissue culture cells were grown in T-75 flasks at 27°C in serum-free medium (Gibco BRL).

Histone isolation and western analysis

Histones were isolated from S2 cells or whole third-instar larvae using an acid extraction protocol modified from Thorne et al. (24). Briefly, cells or larvae were homogenized in 15 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.15 mM spermine, 0.5 mM spermidine, 0.2% NP-40, 10 mM NaF, 1.5 µg/ml aprotinin, 0.7 µg/ml pepstatin, 0.5 µg/ml leupeptin and 1 mM PMSF and nuclei were isolated from the homogenate by pelleting through sucrose. Histones were then extracted in 0.4 M HCl and precipitated with acetone. Histones from ∼107 S2 cells or 40 whole larvae were loaded per sample onto 20 cm SDS–PAGE gels. The separating gels were 18% acrylamide/bisacrylamide (37.5:1) and were run for ∼10 h at 13 mA. Western detection was by chemiluminescence (ECL Kit; Pharmacia). Signals were quantitated using a Molecular Dynamics 595 Fluorimager and ImageQuant software. The fraction of H2Av phosphorylated was always calculated as a ratio of phosphorylated H2Av to total H2Av in each sample.

Photochemically induced DSBs and other DNA-damaging protocols

DSBs were induced photochemically essentially as described by Limoli and Ward (25). Briefly, S2 cells were grown in the presence of 25 µM bromodeoxyuridine for 4 days. Hoechst 33285 was then added to a final concentration of 100 µg/ml and the cells incubated for a further 10 min. Cells were then exposed to 49 995 J/m2 UV-A light (365 nm). Histones were isolated from cells as described above. For induction of general oxidative damage, S2 cells were incubated in the presence of 50 µM H2O2 for 30 min. This level of H2O2 exposure caused 20–30% of the cells to die within 24 h and arrested the cell cycle of all other cells for at least 24 h (unpublished observation). For induction of single-strand breaks in DNA, S2 cells were exposed to 9999 J/m2 UV-C light (254 nm). This level of exposure to UV-C light caused 10–20% of the cells to die within 24 h and arrested the cell cycle of all other cells for at least 24 h (unpublished observation). A 137Cs radiation source was used to irradiate samples at a dose rate of ∼4 Gy/min, as measured by thermoluminescent dosimetry.

Radiation-induced apoptosis assay

Tb+ roaming third-instar larvae of genotypes P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810, P{His2AvΔCTXa};l(3)His2Av810 and P{His2AvWTXa};l(3)His2Av810 were collected from each TM6B balanced stock (see above). Larvae were exposed to 0, 4 or 8 Gy γ-radiation at a dose rate of 4 Gy/min and allowed to recover for 4 h at 23°C. After recovery, wing imaginal discs were dissected from larvae and stained for 8 min in 1 µg/ml acridine orange in EBR (10 mM HEPES, pH 6.9, 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2) and destained for 10 min in EBR. Discs were mounted under a coverslip and allowed to flatten until most cells were spread into a uniform monolayer, which facilitated subsequent analysis and counting. The discs were examined in the fluorescein channel of a fluorescence microscope and the total number of stained nuclei was determined for each disc by manual counting. Apoptotic cells with strongly staining nuclei were first apparent 3 h after irradiation. Recovery times greater than 4 h resulted in a majority of larvae pupating before they could be analyzed. The wing imaginal discs of wildtype and mutant larvae had the same overall size and equivalent cell densities, as determined by DAPI staining (R.L.Glaser, unpublished observation).

Whole animal radiation sensitivity assay

Fifty Tb+ roaming third-instar larvae of genotypes P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810, P{His2AvΔCTXa};l(3)His2Av810 and P{His2AvWTXa};l(3)His2Av810 were collected from each TM6B balanced stock (see above). Larvae were exposed to 0, 10, 20, 30, 40 or 50 Gy γ-radiation at a dose rate of 4 Gy/min and then allowed to continue developing at 23°C. The fraction of larvae surviving to adulthood was measured. A larva was scored as surviving only if the adult produced was fully mobile. Larvae that produced pharate adults that fell into the medium and died before inflating their wings were scored as not surviving. The fraction of larvae that survived without γ-irradiation was set to 100% and all other samples were normalized to that value.

RESULTS

DSBs in DNA induce H2Av phosphorylation

A polyclonal antiserum directed against a peptide homologous to the C-terminal 15 amino acids of H2Av was generated and used to demonstrate that H2Av is phosphorylated in response to γ-irradiation. The antiserum recognized a 14.6 kDa nuclear protein in S2 cells, consistent with earlier studies of H2Av (Fig. 1) (19,26). A slower migrating protein was also detected when the S2 cells were exposed to γ-radiation prior to protein isolation (Fig. 2A). The radiation-induced protein was absent in samples treated with alkaline phosphatase, demonstrating that the protein is generated by radiation-induced phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). Because the H2Av peptide used to generate the antiserum was phosphorylated on what would be Ser137 of H2Av (Fig. 1), phosphorylation-specific antibodies could be isolated using an affinity column containing non- phosphorylated peptide (see Materials and Methods). When such phosphorylation-specific antibodies were used to probe western blots of proteins from control and γ-irradiated S2 cells, only the radiation-induced phosphorylated protein was bound (Fig. 2B). This result is consistent with radiation causing the phosphorylation of H2Av on Ser137.

The possibility that the radiation-induced protein was not phosphorylated H2Av was considered. Radiation could have induced the phosphorylation of an SQ motif in another protein that is fortuitously recognized by antibodies in the H2Av antiserum. Genetic analysis was used to demonstrate that the phosphorylated protein was, in fact, H2Av. A fly strain was obtained that expresses His2AvΔCT, a His2Av gene containing a deletion that removes the C-terminal 15 amino acids of H2Av, including Ser137 (Fig. 1) (23). The 15 C-terminal amino acids of H2Av are not required for the essential function of H2Av and a His2AvΔCT transgene fully rescues the lethality caused by null mutations in His2Av (23). A His2AvΔCT transgene inserted by P-element transformation onto the X chromosome was crossed into a genotype containing l(3)His2Av810, a null allele of His2Av that contains a 311 bp deletion that removes the second exon of the gene (19). P{His2AvΔCT};l(3)His2Av810/TM6B larvae, which express wildtype H2Av from the His2Av gene on the TM6B balancer chromosome, and P{His2AvΔCT};l(3)His2Av810/l(3)His2Av810 larvae, which express only H2AvΔCT from the His2AvΔCT transgene, were both recovered from stock P{His2AvΔCT};l(3)His2Av810/TM6B. Proteins were isolated from third-instar larvae and analyzed by western blotting. Both H2Av and the phosphorylated protein were detected in irradiated P{His2AvΔCT};l(3)His2Av810/TM6B larvae, a result comparable to what was observed in irradiated S2 cells (compare Fig. 2A and C). In contrast, neither H2AvΔCT nor the phosphorylated protein were detected in irradiated P{His2AvΔCT};l(3)His2Av810/l(3)His2Av810 larvae that express only the deleted H2AvΔCT protein (Fig. 2C). The inability to detect H2AvΔCT was expected, since the protein is lacking the 15 C-terminal amino acids against which the anti-peptide H2Av antiserum was generated. H2AvΔCT is present in these animals, since the His2AvΔCT transgene is required to rescue the lethality caused by the l(3)His2Av810 mutation (23). The inability to detect the phosphorylated protein in irradiated P{His2AvΔCT};l(3)His2Av810/l(3)His2Av810 larvae provides compelling evidence that the radiation-induced protein is H2Av phosphorylated at Ser137 and not an unrelated protein fortuitously recognized by the H2Av antiserum.

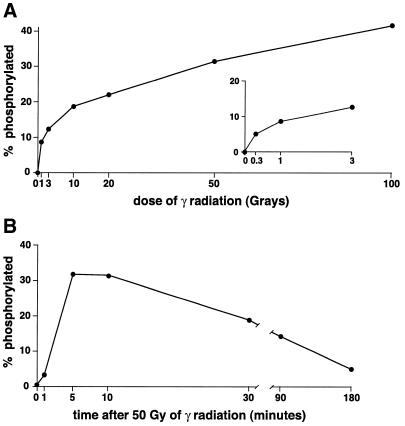

Phosphorylated H2Av was detected with as little as 0.3 Gy of γ-radiation, and the fraction of total H2Av phosphorylated increased with increasing radiation exposure up to at least 100 Gy, although phosphorylation was clearly most efficient at low radiation doses (Fig. 3A). Phosphorylation of H2Av occurred rapidly after DNA breakage. When S2 cells were exposed on ice to 50 Gy and then transferred to medium at 23°C, H2Av phosphorylation was detected within 1 min and was maximal after 5 min. The percentage of phosphorylated H2Av remained maximal for at least 5 min and then declined gradually over several hours (Fig. 3B). The gradual loss of phosphorylated H2Av is likely to be caused by the active dephosphorylation or turnover of H2Av rather than loss of cells due to radiation-induced apoptosis, since apoptotic cell death takes >3 h to occur (see Materials and Methods). Both the dose-response relationship and kinetics of H2Av phosphorylation are very similar to what has been reported for the radiation-induced phosphorylation of H2AX in mammals (6).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of H2Av phosphorylation. (A) Histones were isolated from S2 cells after exposure to increasing amounts of γ-radiation. H2Av was visualized by western blotting using unpurified antiserum against the H2Av phosphopeptide and quantitated by fluorimagery. The percentage of total H2Av phosphorylated is graphed as a function of radiation dose. (B) Histones were isolated from S2 cells at various times after exposure to 50 Gy of γ-radiation. H2Av was visualized by western blotting using unpurified antiserum against the H2Av phosphopeptide and quantitated by fluorimagery. The percentage of total H2Av phosphorylated is graphed as a function of time after radiation exposure.

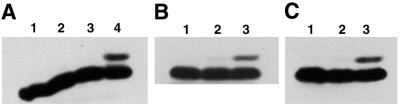

Ionizing radiation creates a variety of cellular damage in addition to DNA DSBs, primarily through the generation of reactive oxygen species. It was important, therefore, to establish that H2Av phosphorylation is induced specifically by DSBs and not by other types of damage to DNA or other macromolecules. DSBs were induced photochemically, without the collateral damage caused by ionizing radiation, by incorporating BrdU into the DNA and then exposing the cells to long wavelength UV-A light in the presence of Hoechst dye (25). Such photochemically created DSBs induced H2Av phosphorylation as efficiently as did γ-irradiation (Fig. 4A). In addition, neither general oxidative damage due to H2O2 exposure nor single-strand breaks induced by short wavelength UV-C light caused H2Av phosphorylation (Fig. 4B and C). These results, in conjunction with those discussed above, establish that H2Av is rapidly phosphorylated on Ser137 in response to DSBs (Figs 2–4).

Figure 4.

H2Av phosphorylation is induced specifically by DSBs. (A) Histones were isolated from S2 cells that were untreated (lane 1), were exposed to UV-A light (lane 2), had incorporated BrdU and been incubated with Hoechst dye (lane 3) or were exposed to UV-A light after incorporation of BrdU and incubation with Hoechst dye (lane 4). H2Av was visualized by western blotting using unpurified antiserum against the H2Av phosphopeptide. (B) Histones were isolated from S2 cells that were untreated (lane 1), incubated with H2O2 (lane 2) or incubated with H2O2 followed by exposure to 100 Gy of γ-radiation (lane 3). H2Av was visualized by western blotting using unpurified antiserum against the H2Av phosphopeptide. (C) Histones were isolated from S2 cells that were untreated (lane 1), exposed to UV-C light (lane 2) or exposed to UV-C light followed by exposure to 100 Gy of γ-radiation (lane 3). H2Av was visualized by western blotting using unpurified antiserum against the H2Av phosphopeptide.

H2Av phosphorylation helps prevent radiation-induced apoptosis

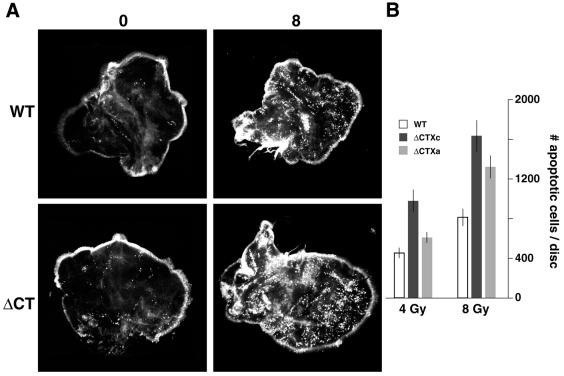

If H2Av phosphorylation has a function in DSB repair, we would predict that a cell lacking H2Av phosphorylation would be more sensitive to radiation and would be more prone to die of radiation-induced apoptosis as a consequence of its reduced ability to repair broken DNA. To test this prediction, we measured the frequency of radiation-induced apoptosis in imaginal disc cells of P{His2AvΔCT};l(3)His2Av810 larvae that are unable to phosphorylate H2Av, and in P{His2AvWT};l(3)His2Av810 control larvae that express wildtype H2Av in an otherwise identical genetic background. Apoptotic cells were identified by staining dissected wing discs with acridine orange, which preferentially stains nuclei of apoptotic cells and makes them brightly fluorescent in the fluorescein channel of a fluorescence microscope (see Materials and Methods) (27). The number of apoptotic cells in each disc was measured by manually counting the number of fluorescing nuclei.

Imaginal discs from larvae lacking H2Av phosphorylation had significantly more radiation-induced apoptotic cells than did discs from wildtype larvae (Fig. 5). In the absence of γ-irradiation, discs from both mutant and wildtype larvae had about 300 apoptotic cells (Fig. 5A). Specifically, discs from P{His2AvWT};l(3)His2Av810 larvae had 331 ± 31 (n = 12), discs from P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810 larvae had 274 ± 40 (n = 12) and discs from P{His2AvΔCTXa};l(3)His2Av810 larvae had 286 ± 26 (n = 12). Whatever causes apoptosis in the absence of irradiation appears to be unaffected by H2Av phosphorylation. In contrast, discs from P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810 mutant larvae that are unable to phosphorylate H2Av had 2-fold more apoptotic cells at both 4 Gy (P < 0.001; two-tailed t-test assuming unequal variances) and 8 Gy irradiation (P < 0.0008; Fig. 5A and B). Discs from P{His2AvΔCTXa};l(3)His2Av810 mutant larvae, which have a P{His2AvΔCT} transposon inserted at a different location on the X chromosome, had a more modest 1.3-fold increase in apoptotic cells at 4 Gy (P < 0.08) and a 1.6-fold increase at 8 Gy (P < 0.002; Fig. 5B). Discs from larvae of the same mutant genotypes but derived from homozygous mutant parents lacking wildtype H2Av, as opposed to those having heterozygous parents that were used for the analysis shown in Figure 5, had the same degree of radiation sensitivity, indicating that maternal wildtype H2Av did not suppress the frequency of apoptotic cells (data not shown). Finally, similar increases in radiation-induced apoptosis were also observed in eye/antennal and leg discs (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Imaginal cells unable to phosphorylate H2Av are radiation sensitive. (A) Larvae expressing either wildtype H2Av (WT), which is phosphorylated, or H2Av deleted of its C-terminus (ΔCT), which is not phosphorylated, were exposed to 0 or 8 Gy of γ-radiation. Apoptotic cells were identified in dissected imaginal wing discs by staining with acridine orange. Nuclei of apoptotic cells stain brightly and appear as sharp pinpoints of light in the images shown. The ΔCT discs illustrated are from larvae of genotype P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810. The numbers of apoptotic cells counted were 370 (0 Gy) and 1146 (8 Gy) for the wildtype discs illustrated and 288 (0 Gy) and 2088 (8 Gy) for the ΔCT discs. (B) The number of radiation-induced apoptotic cells per disc was quantitated by counting the total number of fluorescent nuclei in discs irradiated with either 4 or 8 Gy of γ-radiation and subtracting the average number of fluorescent nuclei observed in unirradiated discs of the same genotype. Larvae of genotype P{His2AvWT};l(3)His2Av810, which express wildtype H2Av (open column), and larvae of genotypes P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810 and P{His2AvΔCTXa};l(3)His2Av810, two independent strains expressing H2Av deleted of its C-terminus (gray columns), were analyzed. Mean and standard errors were calculated from 9–12 independent measurements for each sample.

The radiation-sensitive phenotype is likely to be caused solely and specifically by the lack of H2Av phosphorylation at Ser137 and not by any other unanticipated consequence of the deletion of 15 amino acids of the H2Av C-terminus. The C-terminal 15 amino acids of H2Av are not known to encode any functions other than DSB-induced phosphorylation. The amino acids are not required for the essential functions of H2Av (23); the C-terminal tail has no homology outside the SQ motif involved in phosphorylation to the C-terminal tails of H2AZ or H2AX histones in other organisms (5); and the ΔCT mutation leaves a C-terminal tail of six amino acids and is therefore unlikely to have a detrimental impact on the structure or function of the globular domain of H2Av, given that the normal C-terminal tail of H2A is only seven amino acids long (Fig. 1).

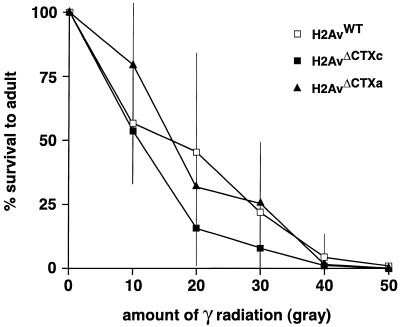

Finally, the 2-fold increase in radiation-induced apoptosis of imaginal disc cells did not cause a concomitant increase in lethality. Specifically, the percentage of irradiated roaming stage third-instar larvae to complete metamorphosis and emerge as pharate adults did not differ between larvae that could or could not phosphorylate H2Av, irrespective of radiation dose (Fig. 6). This was also true of early third-instar larvae as well as 24 h pupae (data not shown). The 2-fold increase in imaginal-cell apoptosis might have only negligible effects on overall disc development and morphogenesis, or perhaps is a level of cell loss for which the imaginal disc is able to compensate by increased proliferation of viable cells. We also measured the radiation sensitivity of embryos and adults, and again found no difference between animals that could and could not phosphorylate H2Av (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Larvae that lack H2Av phosphorylation are not radiation sensitive. Third-instar larvae of genotype P{His2AvWT};l(3)His2Av810 that can phosphorylate H2Av (open boxes) and larvae of genotypes P{His2AvΔCTXc};l(3)His2Av810 and P{His2AvΔCTXa};l(3)His2Av810 that lack H2Av phosphorylation (filled boxes and filled triangles, respectively) were exposed to increasing amounts of γ-radiation. The percentage of larvae that survived to adulthood was measured and is graphed as a function of radiation dose. Mean and standard deviations were calculated from the results of at least three independent measurements.

DISCUSSION

Drosophila H2Av is unique among histone variants, providing in a single histone both the transcription function of H2AZ variants and the DNA repair function of H2AX variants. Ser137 in the C-terminus of H2Av is phosphorylated in response to DSBs and preventing this phosphorylation causes imaginal disc cells to become radiation sensitive (Figs 2–5). These observations support the conclusion that H2Av phosphorylation contributes to repair of DSBs and that H2Av is the functional homolog in flies of mammalian H2AX. The amino acid sequence of H2Av outside its C-terminal tail clearly identifies H2Av as the H2AZ ortholog in Drosophila. The H2AZ function provided by H2Av is essential for normal fly development and is likely involved in chromatin-mediated regulation of transcription, although a function in transcription has yet to be directly demonstrated in flies (18–22). The juxtaposition of both DNA repair and transcription functions in a single variant histone distinguishes H2Av in Drosophila from the situation in both yeast and mammals, in which these functions are provided by separate H2AX and H2AZ histones.

The phosphorylation of H2Av in Drosophila is also distinct from DSB-induced phosphorylation in yeast and mammals in that the histone phosphorylated is specifically an H2AZ variant. Mammalian H2AX outside its C-terminal tail is almost identical to H2A, differing at only three of 120 residues, and H2A is the histone phosphorylated in yeast (7,11). The phosphorylation of H2Av in Drosophila suggests that an H2AZ variant can make the same contribution to DNA repair as does H2A, assuming that DSB-induced phosphorylation in mammals, flies and yeast facilitates repair by a single mechanism. The equivalence of H2AZ and H2A histones with respect to DNA repair was not necessarily expected, given that H2AZ and H2A are not equivalent with respect to their functions in transcription. H2A cannot functionally replace H2AZ in flies or yeast and H2AZ cannot functionally replace H2A, at least in yeast, in which such an experiment can be done (23,28). Perhaps H2Av in flies, H2AX in mammals and H2A in yeast function equivalently with respect to DNA repair because their C-terminal tails, the substrates for DSB-induced phosphorylation, are located in the same position along the chromatin fiber. The C-terminal tail of all H2A histones extends from the nucleosome near the position where linker DNA enters and exits, and H2A C-termini can directly interact with linker DNA (29,30). Since the tails are in the same location, it is reasonable to assume that phosphorylation of those tails would have comparable effects. If the location of the C-terminal tail is, in fact, all that matters for DNA repair, this would also imply that any unique functions provided by the globular domains of H2AZ or H2A are unrelated to, and likely unaffected by, the mechanism by which phosphorylation of the C-terminal tail facilitates repair. This is a particularly interesting issue with respect to H2AZ variants, because they may be involved in regulating the equilibrium among differing states of chromatin compaction (31).

Identification of a function for H2Av in DNA repair also provided an explanation for a puzzling aspect of the pattern of localization of H2Av in the Drosophila genome, which was characterized previously. H2Av-containing nucleosomes are found associated with DNA sequences located through the genome, including non-coding satellite sequences within heterochromatin (26). The association of H2Av with non-coding satellite sequences would be difficult to understand if the only function of H2Av was in transcriptional regulation. Identification of a function for H2Av in DNA repair provides a plausible explanation for why H2Av would be associated with non-coding sequences. A DSB located anywhere in the genome is a potentially lethal lesion, so some amount of H2Av-containing nucleosomes might need to be associated with all sequences of the genome to ensure that repair can be facilitated wherever a DSB might occur.

In addition to the localization of H2Av to all regions of the Drosophila genome, the density of H2Av-containing nucleosomes also varies significantly and frequently along the length of each chromosome arm (26). While variations in density are likely to be a general characteristic of H2AZ variants, this pattern is quite different from the uniform distribution observed for mammalian H2AX and yeast H2A (6,20). The fact that H2Av functions in both transcription and repair demonstrates that both functions can be compatible with the localization pattern of a single histone; it suggests, more generally, that H2AZ and H2AX variants do not require mutually exclusive locations in the genome to provide their respective functions. The variation in H2Av density also raises the possibility that the efficiency of DSB repair could vary among different regions in the Drosophila genome, if it were the case that the density of H2Av in any given region of chromatin influenced the extent to which DSB-induced phosphorylation facilitated repair. Alternatively, a minimum density of H2Av-containing nucleosomes might be sufficient to provide the function of H2Av in repair and increases in density above that minimum might be necessary for the essential function of H2Av in transcription, but would not influence repair.

Overall, the phenotype of Drosophila lacking H2Av phosphorylation is quite modest. Radiation sensitivity in larvae unable to phosphorylate H2Av increased 2-fold when assayed at the level of imaginal cell apoptosis and no increase in sensitivity was observed at the level of larval lethality (Figs 5 and 6). If H2Av phosphorylation were an essential step in the DSB repair pathway, radiation-induced larval lethality would be expected to increase substantially. For example, mutation of specific repair proteins, such as DmRAD54, can increase radiation-induced lethality 7-fold, and if a second repair gene is mutated simultaneously the increase in radiation-induced lethality can reach nearly 40-fold (32). In the light of these observations, the modest phenotype described in this report suggests that H2Av phosphorylation promotes repair efficiency rather than being an essential step in the repair process itself. A similar conclusion is suggested by genetic analyses of DSB-induced phosphorylation of H2A in budding yeast. Prevention of H2A phosphorylation increased the sensitivity of yeast to radiomimetic drugs, but it only reduced NHEJ repair about 2-fold and appeared to have little or no effect on HR (11). The phenotype of H2AX knockout mice also suggests that H2AX phosphorylation in mammals is probably not essential for most mechanisms of DSB repair, although H2AX phosphorylation in mice does appear to be more important for some types of repair than is DSB-induced phosphorylation for repair in either yeast or flies. Mice lacking H2AX are growth retarded, radiation sensitive and male sterile (12). In contrast, Drosophila lacking H2Av phosphorylation grow at normal rates, larvae are no more radiation sensitive than the wildtype and both sexes are fertile (Fig. 6; R.L.Glaser, unpublished observations). So, genetic analyses of DSB-induced phosphorylation of H2A histones in yeast, flies and mice are consistent with the general conclusion that the function of phosphorylation is to facilitate repair efficiency. The phenotype of H2AX knockout mice further suggests that during evolution phosphorylation of H2AX in mammals acquired greater importance for particular DSB repair processes.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank David Tremethick and Michael Clarkson for fly strains, Randall Morse for critical reading of the manuscript and the Wadsworth Center Peptide Synthesis Core Facility for technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH to R.L.G.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khanna K.K. and Jackson,S.P. (2001) DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nature Genet., 27, 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takata M., Sasaki,M.S., Sonoda,E., Morrison,C., Hashimoto,M., Utsumi,H., Yamaguchi-Iwai,Y., Shinohara,A. and Takeda,S. (1998) Homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways of DNA double-strand break repair have overlapping roles in the maintenance of chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells. EMBO J., 17, 5497–5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastink A. and Lohman,P.H.M. (1999) Repair and consequences of double-strand breaks in DNA. Mutat. Res., 428, 141–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modesti M. and Kanaar,R. (2001) DNA repair: spot(light)s on chromatin. Curr. Biol., 11, R229–R232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redon C., Pilch,D., Rogakou,E., Sedelnikova,O., Newrock,K. and Bonner,W. (2002) Histone H2A variants H2AX and H2AZ. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 12, 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogakou E.P., Pilch,D.R., Orr,A.H., Ivanova,V.S. and Bonner,W.M. (1998) DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 5858–5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannironi C., Bonner,W.M. and Hatch,C.L. (1989) H2A.X, a histone isoprotein with a conserved C-terminal sequence, is encoded by a novel mRNA with both DNA replication type and polyA 3′ processing signals. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 9113–9126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J. and Ward,I.M. (2001) Histone H2AX is phosphorylated in an ATR-dependent manner in response to replicational stress. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 47759–47762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burma S., Chen,B.P., Murphy,M., Kurimasa,A. and Chen,D.J. (2001) ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 42462–42467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogakou E.P., Boon,C., Redon,C. and Bonner,W.M. (1999) Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J. Cell Biol., 146, 905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downs J.A., Lowndes,N.F. and Jackson,S.P. (2000) A role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone H2A in DNA repair. Nature, 408, 1001–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celeste A., Petersen,S., Romanienko,P.J., Fernandez-Capetillo,O., Chen,H.T., Sedelnikova,O.A., Reina-San-Martin,B., Coppola,V., Meffre,E., Difilippantonio,M.J., Redon,C., Pilch,D.R., Olaru,A., Eckhaus,M., Camerini-Otero,D., Tessarollo,L., Livak,F., Manova,K., Bonner,W.M., Nussenzweig,M.C. and Nussenzweig,A. (2002) Genomic instability in mice lacking histone H2AX. Science, 296, 922–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogakou E.P., Nieves-Neira,W., Boon,C., Pommier,Y. and Bonner,W.M. (2000) Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 9390–9395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H.T., Bhandoola,A., Difilippantonio,M.J., Zhu,J., Brown,M.J., Tai,X., Rogakou,E.P., Brotz,T.M., Bonner,W.M., Ried,T. and Nussenzweig,A. (2000) Response to RAG-mediated V(D)J cleavage by NBS1 and γ-H2AX. Science, 290, 1962–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahadevaiah S.K., Turner,J.M.A., Baudat,F., Rogakou,E.P., de Boer,P., Blanco-Rodriguez,J., Jasin,M., Keeney,S., Bonner,W.M. and Burgoyne,P.S. (2001) Recombinational DNA double-strand breaks in mice precede synapsis. Nature Genet., 27, 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen S., Casellas,R., Reina-San-Martin,B., Chen,H.T., Difilippantonio,M.J., Wilson,P.C., Hanitsch,L., Celeste,A., Muramatsu,M., Pilch,D.R., Redon,C., Rieds,T., Bonner,W.M., Honjo,T., Nussenzweig,M.C. and Nussenzweig,A. (2001) AID is required to initiate Nbs1/-H2AX focus formation and mutations at sites of class switching. Nature, 414, 660–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limoli C.L., Giedzinski,E., Bonner,W.M. and Cleaver,J.E. (2002) UV-induced replication arrest in the xeroderma pigmentosum variant leads to DNA double-strand breaks, γ-H2AX formation and Mre11 relocalization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Daal A., White,E.M., Gorovsky,M.A. and Elgin,S.C.R. (1988) Drosophila has a single copy of the gene encoding a highly conserved histone H2A variant of the H2A.F/Z type. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 7487–7497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Daal A. and Elgin,S.C.R. (1992) A histone variant, H2AvD, is essential in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Cell, 3, 593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santisteban M.S., Kalashnikova,T. and Smith,M.M. (2000) Histone H2A.Z regulates transcription and is partially redundant with nucleosome remodeling complexes. Cell, 103, 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhillon N. and Kamakaka,R.T. (2000) A histone variant, Htz1p, and a Sir1p-like protein, Esc2p, mediate silencing at HMR. Mol. Cell, 6, 769–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adam M., Robert,F., Larochelle,M. and Gaudreau,L. (2001) H2A.Z is required for global chromatin integrity and for recruitment of RNA polymerase II under specific conditions. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 6270–6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarkson M.J., Wells,J.R.E., Gibson,F., Saint,R. and Tremethick,D.J. (1999) Regions of variant histone His2AvD required for Drosophila development. Nature, 399, 694–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorne A.W., Cary,P.D. and Crane-Robinson,C. (1998) Extraction and separation of core histones and non-histone chromosomal proteins. In Gould,H. (ed.), Chromatin—A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 35–57.

- 25.Limoli C.L. and Ward,J.F. (1993) A new method for introducing double-strand breaks into cellular DNA. Radiat. Res., 134, 160–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leach T.J., Mazzeo,M., Chotkowski,H.L., Madigan,J.P., Wotring,M.G. and Glaser,R.L. (2000) Histone H2A.Z is widely but nonrandomly distributed in chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 23267–23272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abrams J.M., White,K., Fessler,L.I. and Steller,H. (1993) Programmed cell death during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development, 117, 29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson J.D. and Gorovdky,M.A. (2000) Histone H2A.Z has a conserved function that is distinct from that of the major H2A sequence variants. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3811–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luger K., Mäder,A.W., Richmond,R.K., Sargent,D.F. and Richmond,T.J. (1997) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8Å resolution. Nature, 389, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindsey G.G., Orgeig,S., Thompson,P., Davies,N. and Maeder,D.L. (1991) Extended C-terminal tail of wheat histone H2A interacts with DNA of the ‘linker’ region. J. Mol. Biol., 218, 805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan J.Y., Gordon,F., Luger,K., Hansen,J.C. and Tremethick,D.J. (2002) The essential histone variant H2A.Z regulates the equilibrium between different chromatin conformational states. Nature Struct. Biol., 9, 172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kooistra R., Pastink,A., Zonneveld,J.B.M., Lohman,P.H.M. and Eeken,J.C.J. (1999) The Drosophila melanogaster DmRAD54 gene plays a crucial role in double-strand break repair after P-element excision and acts synergistically with Ku70 in the repair of X-ray damage. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 6269–6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]