Abstract

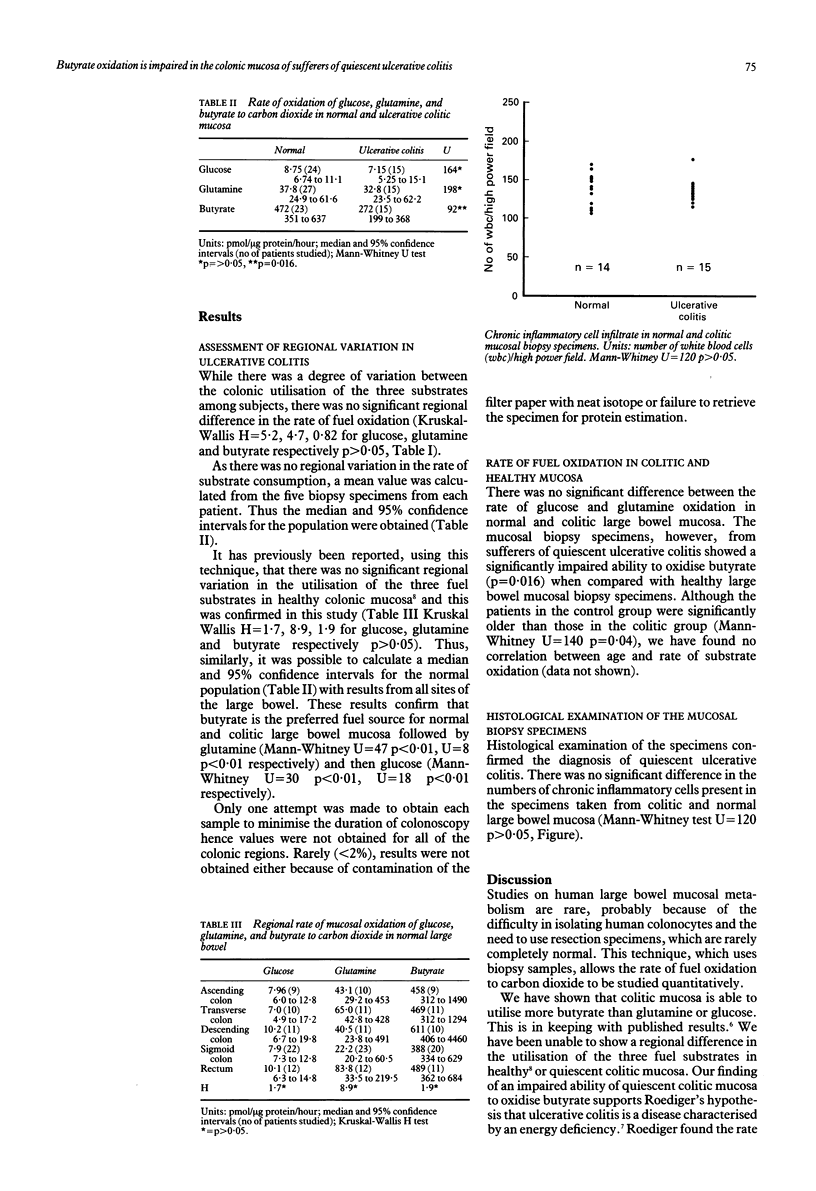

The short chain fatty acids, acetate, propionate, and butyrate are produced by colonic bacterial fermentation of non-starch polysaccharides. Butyrate is the major fuel source for the colonic epithelium and there is evidence to suggest that its oxidation is impaired in ulcerative colitis. Triplicate biopsy specimens were taken at colonoscopy from five regions of the large bowel in 15 sufferers of ulcerative colitis. These patients all had mild or quiescent colitis as assessed by clinical condition, mucosal endoscopic and histological appearance. The rate of oxidation of glucose, glutamine, and butyrate through to carbon dioxide was compared with that in biopsy specimens from 28 patients who had no mucosal abnormality. Butyrate (272 (199-368)) was the preferred fuel source for the colitic mucosa followed by glutamine (33 (24-62)) then glucose (7.2 (5.3-15)) pmol/micrograms/hour; medians and 95% confidence intervals, p < 0.01. There was no regional difference in the rate of utilisation of these metabolites. In the group with colitis the rate of butyrate oxidation to carbon dioxide was significantly impaired compared with that in normal mucosa decreasing from 472 (351-637) pmol/micrograms/hour to 272 (199-368) pmol/micrograms/hour; median and 95% confidence intervals, p = 0.016. The rate of glucose and glutamine utilisation were not significantly different between normal and colitic mucosa. These data confirm that in quiescent ulcerative colitis there is an impairment of butyrate oxidation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Breuer R. I., Buto S. K., Christ M. L., Bean J., Vernia P., Paoluzi P., Di Paolo M. C., Caprilli R. Rectal irrigation with short-chain fatty acids for distal ulcerative colitis. Preliminary report. Dig Dis Sci. 1991 Feb;36(2):185–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01300754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman M. A., Grahn M. F., Giamundo P., O'Connell P. R., Onwu D., Hutton M., Maudsley J., Norton B., Rogers J., Williams N. S. New technique to measure mucosal metabolism and its use to map substrate utilization in the healthy human large bowel. Br J Surg. 1993 Apr;80(4):445–449. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H., Pomare E. W., Branch W. J., Naylor C. P., Macfarlane G. T. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987 Oct;28(10):1221–1227. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H. Short chain fatty acids in the human colon. Gut. 1981 Sep;22(9):763–779. doi: 10.1136/gut.22.9.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipe M. I., Branfoot A. C. Abnormal patterns of mucus secretion in apparently normal mucosa of large intestine with carcinoma. Cancer. 1974 Aug;34(2):282–290. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197408)34:2<282::aid-cncr2820340211>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning S. J., Hird F. J. Ketogenesis from butyrate and acetate by the caecum and the colon of rabbits. Biochem J. 1972 Dec;130(3):785–790. doi: 10.1042/bj1300785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil N. I., Cummings J. H., James W. P. Short chain fatty acid absorption by the human large intestine. Gut. 1978 Sep;19(9):819–822. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.9.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger W. E. Role of anaerobic bacteria in the metabolic welfare of the colonic mucosa in man. Gut. 1980 Sep;21(9):793–798. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.9.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger W. E. The colonic epithelium in ulcerative colitis: an energy-deficiency disease? Lancet. 1980 Oct 4;2(8197):712–715. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombeau J. L., Kripke S. A. Metabolic and intestinal effects of short-chain fatty acids. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1990 Sep-Oct;14(5 Suppl):181S–185S. doi: 10.1177/014860719001400507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheppach W., Sommer H., Kirchner T., Paganelli G. M., Bartram P., Christl S., Richter F., Dusel G., Kasper H. Effect of butyrate enemas on the colonic mucosa in distal ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992 Jul;103(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91094-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senagore A. J., MacKeigan J. M., Scheider M., Ebrom J. S. Short-chain fatty acid enemas: a cost-effective alternative in the treatment of nonspecific proctosigmoiditis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992 Oct;35(10):923–927. doi: 10.1007/BF02253492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk D. B. Fibre and enteral nutrition. Gut. 1989 Feb;30(2):246–264. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernia P., Gnaedinger A., Hauck W., Breuer R. I. Organic anions and the diarrhea of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988 Nov;33(11):1353–1358. doi: 10.1007/BF01536987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windmueller H. G., Spaeth A. E. Identification of ketone bodies and glutamine as the major respiratory fuels in vivo for postabsorptive rat small intestine. J Biol Chem. 1978 Jan 10;253(1):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]