Abstract

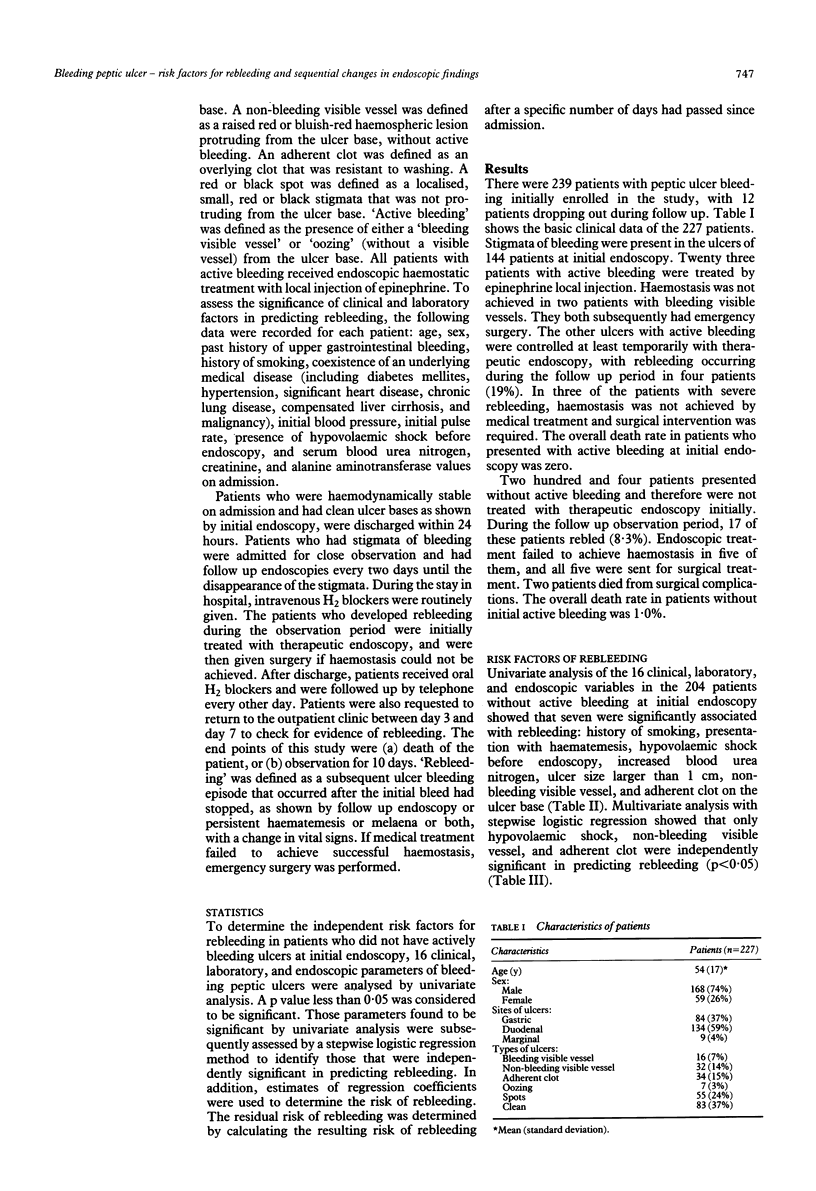

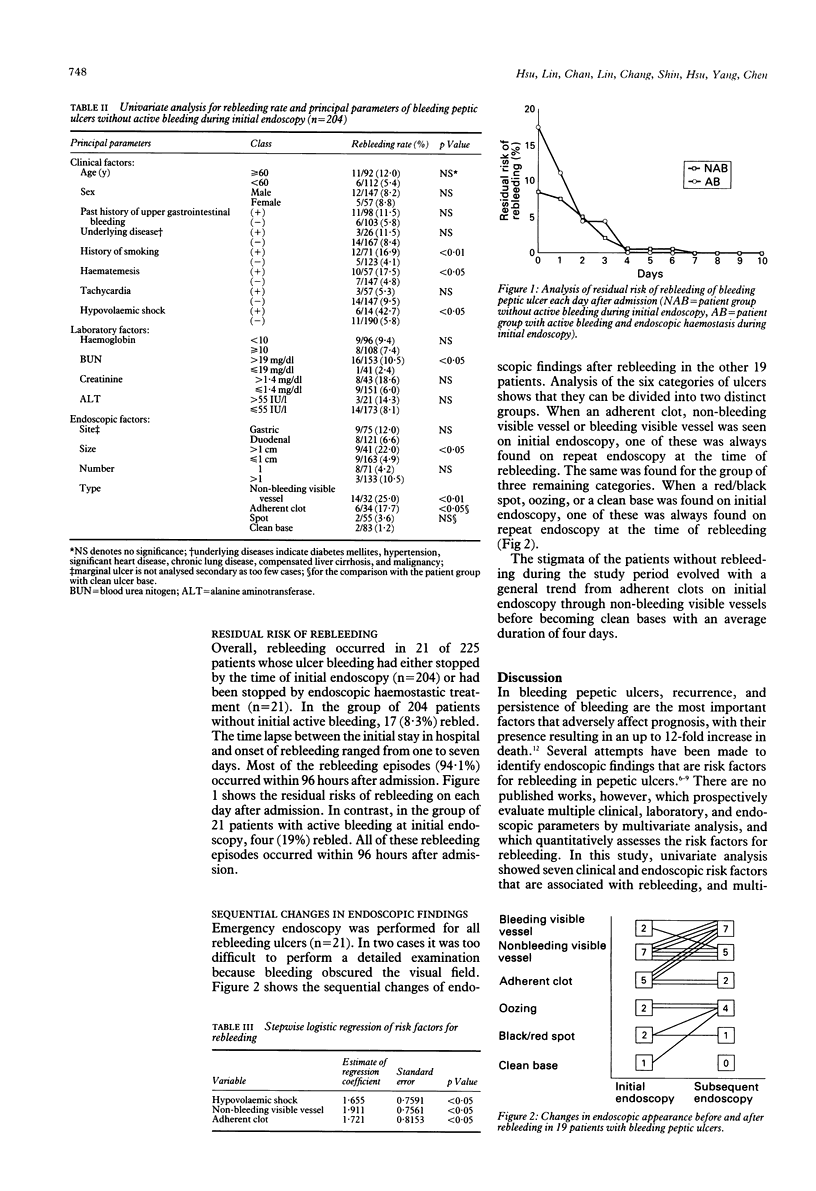

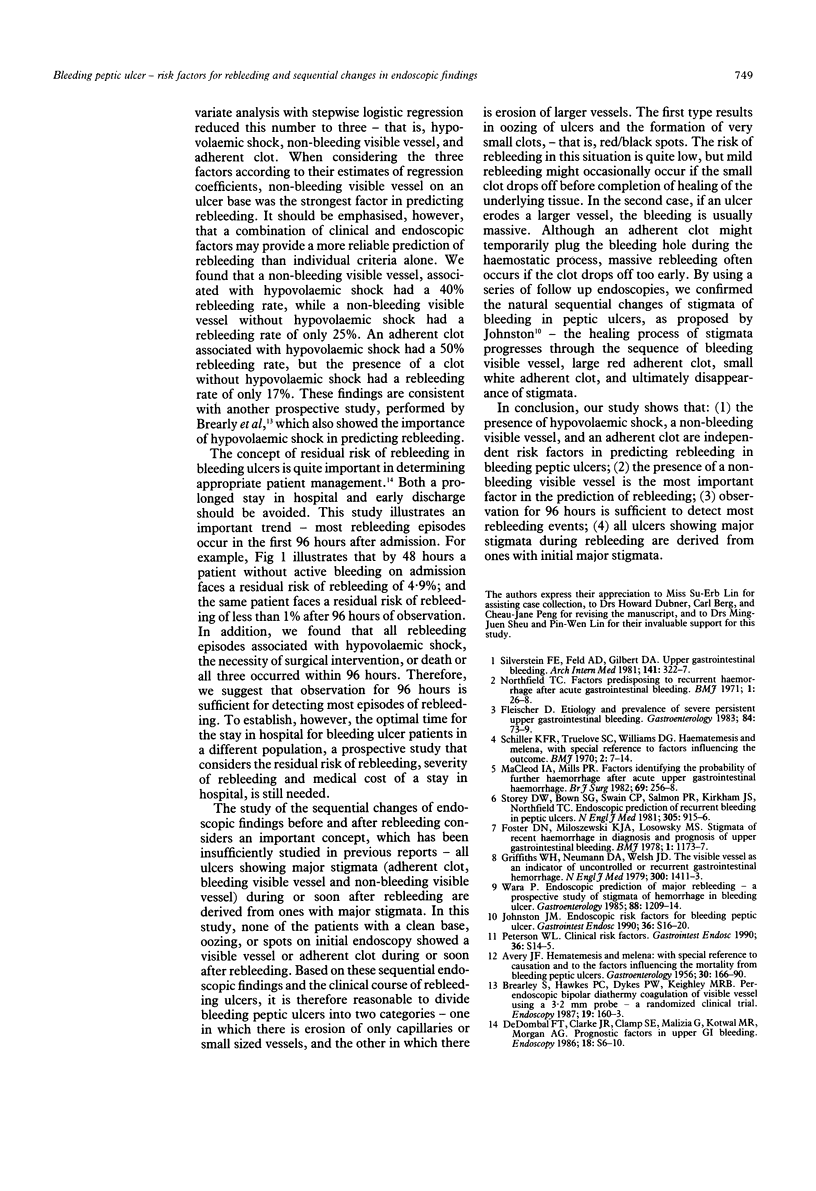

From September 1991 to December 1992, a prospective study was conducted to determine the risk factors and residual risk of rebleeding, and the evolutionary endoscopic changes in peptic ulcers that rebled. Emergency endoscopies were performed on 452 patients with haematemesis or a melaena, or both within 24 hours of admission. If the lesions were actively bleeding, then the patients were treated with injection sclerotherapy. A multivariate analysis of clinical, laboratory, and endoscopic variables of 204 patients with ulcer bleeding showed that hypovolaemic shock, a non-bleeding visible vessel, and an adherent clot on the ulcer base were independently significant in predicting rebleeding (p < 0.05). Considering these three factors according to the estimates of their regression coefficients showed that a non-bleeding visible vessel was the strongest predictor of rebleeding. The study of the residual risk of rebleeding after admission showed that most rebleeding episodes (94.1%), including all associated with hypovolaemic shock, surgical treatment, and death, occurred within 96 hours of admission. After this time, the residual risk of rebleeding was less than 1%. Study of the changes in endoscopic findings before and after rebleeding illustrated that all ulcers with a visible vessel or adherent clot showed at follow up endoscopy were derived from ulcers with initial major stigmata. It is concluded that hypovolaemic shock, a non-bleeding visible vessel, and an adherent clot on an ulcer base are of independent significance in predicting rebleeding. Observation for 96 hours is sufficient to detect most rebleeding episodes after an initial bleed from peptic ulcer.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brearley S., Hawker P. C., Dykes P. W., Keighley M. R. Per-endoscopic bipolar diathermy coagulation of visible vessels using a 3.2 mm probe--a randomised clinical trial. Endoscopy. 1987 Jul;19(4):160–163. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster D. N., Miloszewski K. J., Losowsky M. S. Stigmata of recent haemorrhage in diagnosis and prognosis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Br Med J. 1978 May 6;1(6121):1173–1177. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6121.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths W. J., Neumann D. A., Welsh J. D. The visible vessel as an indicator of uncontrolled or recurrent gastrointestinal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 1979 Jun 21;300(25):1411–1413. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906213002503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES F. A. Hematemesis and melena; with special reference to causation and to the factors influencing the mortality from bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastroenterology. 1956 Feb;30(2):166–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J. H. Endoscopic risk factors for bleeding peptic ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990 Sep-Oct;36(5 Suppl):S16–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod I. A., Mills P. R. Factors identifying the probability of further haemorrhage after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1982 May;69(5):256–258. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800690509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northfield T. C. Factors predisposing to recurrent haemorrhage after acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Br Med J. 1971 Jan 2;1(5739):26–28. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5739.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson W. L. Therapeutic endoscopy and bleeding ulcers. Clinical risk factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990 Sep-Oct;36(5 Suppl):S14–S15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller K. F., Truelove S. C., Williams D. G. Haematemesis and melaena, with special reference to factors influencing the outcome. Br Med J. 1970 Apr 4;2(5700):7–14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5700.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein F. E., Feld A. D., Gilbert D. A. Upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Predisposing factors, diagnosis, and therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1981 Feb 23;141(3 Spec No):322–327. doi: 10.1001/archinte.141.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey D. W., Bown S. G., Swain C. P., Salmon P. R., Kirkham J. S., Northfield T. C. Endoscopic prediction of recurrent bleeding in peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med. 1981 Oct 15;305(16):915–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198110153051603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wara P. Endoscopic prediction of major rebleeding--a prospective study of stigmata of hemorrhage in bleeding ulcer. Gastroenterology. 1985 May;88(5 Pt 1):1209–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Dombal F. T., Clarke J. R., Clamp S. E., Malizia G., Kotwal M. R., Morgan A. G. Prognostic factors in upper G.I. bleeding. Endoscopy. 1986 May;18 (Suppl 2):6–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]