Abstract

By using sequence information from an aligned protein family, a procedure is exhibited for finding sites that may be functionally or structurally critical to the protein. Features based on sequence conservation within subfamilies in the alignment and associations between sites are used to select the sites. The sites are subject to statistical evaluation correcting for phylogenetic bias in the collection of sequences. This method is applied to two families: the phycobiliproteins, light-harvesting proteins in cyanobacteria, red algae, and cryptomonads, and the globins that function in oxygen storage and transport. The sites identified by the procedure are located in key structural positions and merit further experimental study.

Fundamental problems in proteomics include both identifying and understanding the role of the essential sites that determine the structure and proper functioning of the molecule. A thorough evaluation of the importance of all sequence sites involves extremely time-consuming and laborious biochemical experimental methods. Our goal is to determine a candidate set of such sites by considering only the sequence information from a protein family alignment. In this article we use two particular features in the sequence data for identifying sites, develop statistical evaluation methods, and apply the procedure to two well studied protein families: the phycobiliproteins and the globins. Finally, we show that the collection of sites identified by our procedure is distinguishable with respect to specific structural attributes.

Methods

It is generally accepted that the residues most critical to the function of a protein are the most rigorously conserved (1). For example, the Phe and His residues that are involved in heme binding are both conserved in the aligned sequences of all known functional myoglobins (Mbs), α- and β-globins, the globins of invertebrates, and in the plant leghemoglobins. Besides such globally conserved examples of functionally critical positions, other sites of interest include those that show residue variation and are responsible for functional differences within a family. The chief difficulty, of course, is locating such sites. Suppose that we are given a functionally distinguished subfamily of a protein family. It seems plausible that a site playing a role in this particular function will be conserved within the family. On the other hand, we may ask that such a site should distinguish the subfamily from all other sequences in the protein family, which is accomplished by requiring that all other sequences have a residue different from the one conserved in the subfamily in the specified site. In practice, there may not be such functionally distinguished subfamilies so that we need to identify subfamilies and sites simultaneously.

More formally, we are given a family ℱ of sequences and a biologically functional subfamily ℱo ⊂ ℱ. We look for sites that satisfy the following criteria: (i) are conserved in ℱo and (ii) have a very different residue distribution in the complement of the family, ℱ . In practice, the functional subfamilies ℱo may not be known.

. In practice, the functional subfamilies ℱo may not be known.

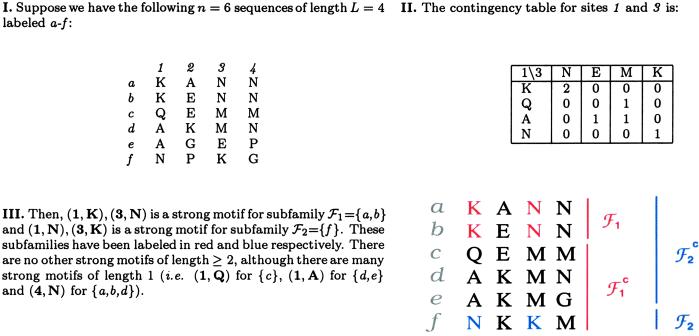

Thus, we enumerate all subfamilies in the family according to these criteria using the strictest version of criterion ii: all the sequences in the complement ℱ have a different residue than the one conserved in ℱo. A site-residue (S-R) that satisfies this condition is called a strong S-R for ℱo. Subfamilies that have at least two strong S-Rs are called strong-motif families, and the set of corresponding S-Rs is called a strong motif. All such families and sites can be found in O(n2L2) operations (see Appendix for algorithm). Clearly, corresponding to any single S-R there exists a subfamily having it as a strong-motif pair; thus we limit our search for strong-motif families with at least two S-Rs. However, it is also evident that there may be no subfamilies having strong motifs of length ≥2.∥ Fig. 1 shows an example illustrating these definitions.

have a different residue than the one conserved in ℱo. A site-residue (S-R) that satisfies this condition is called a strong S-R for ℱo. Subfamilies that have at least two strong S-Rs are called strong-motif families, and the set of corresponding S-Rs is called a strong motif. All such families and sites can be found in O(n2L2) operations (see Appendix for algorithm). Clearly, corresponding to any single S-R there exists a subfamily having it as a strong-motif pair; thus we limit our search for strong-motif families with at least two S-Rs. However, it is also evident that there may be no subfamilies having strong motifs of length ≥2.∥ Fig. 1 shows an example illustrating these definitions.

Fig 1.

An example illustrating the strong-motif algorithm.

The first feature differentiates sites by their residue identity within and outside subfamilies. There is no explicit evaluation of relationships between the sites, although by construction strong-motif sites are perfectly covarying within the strong-motif family. By our second feature for site selection, we explore relationships between the strong-motif sites. We look for the strong-motif site pairs that, in general, are strongly covarying. A strong association between two sites may not necessarily indicate a structural interaction. From the data, it is impossible to make the causal inference that sites directly influence each other or to infer the direction of the influence. There are any number of situations that may create a strong association between sites besides direct contact. Furthermore, there is evidence that long-range interactions are also critical for the proper functioning of a protein (2, 3). In conclusion, when a site appears in highly significant associations, we consider this as stronger evidence for being potentially critical to the molecule. Thus, we will consider the strong-motif sites that are in statistically significant pairs as potentially important sites to the molecule.

All pairs between strong-motif sites i and j, within each detected strong motif, are evaluated for statistical covariation by using the measures described in ref. 4. The statistics used in ref. 4 measure the degree of association between two sites.

Assessing Significance

We shall now elaborate on how the statistical significance of the covariation features discussed above is determined. We can assess significance under the following two sets of assumptions, which we contrast below. We conclude that the second set is more stringent than the first and rely on its resulting assessment for our selection of sites.

Set I A1: Sites evolve independently. A20: Sequences are independent.

Set II A10: Sites evolve independently and identically.

A2: Sequences evolve under an evolutionary model on a phylogenetic tree.

The assumption of independence is clearly consistent with changes in the genome due to point mutations but not insertions and deletions. It is made explicitly or implicitly by existing approaches to finding functional motifs such as MEME (5) and EMOTIF (6). Thus, A1 seems reasonable.

A20 cannot be true, because all proteins correspond to leaves of an evolutionary tree. It is made implicitly in the work of Stormo and Hartzell (7) and Lawrence and Reilly (8) leading up to MEME. The extent to which A20 provides a good approximation depends on parameters such as the time to the most recent common ancestor of the species under consideration and the rate of mutation at sites assumed to be neutral in the sequences coding for the proteins, parameters which are not readily ascertainable.

Of course, identical evolution A10 is an unrealistic assumption. Most nonneutral sites evolve at different rates and with dissimilar residue distributions due to inhomogeneous selection pressures. However, we use it for the null model that sites are not functionally important and hence neutral. Essentially, A1 is more realistic than A10 and A2 is more realistic than A20.

Although we found assumption A20 held up well in a sample of unrelated bacterial sequences, when we contrasted A2 and A20 on the phycobiliproteins, it became clear that Set I was untenable as a null hypothesis. In particular, if sequences were assumed to be independent, then ≈8% of all pairs show highly significant statistical association, whereas if we account for the phylogeny as detailed below, only 0.1% of the pairs are found significant at the same level. Thus, the strong covariation exhibited by many of the pairs is no longer significant once the dependence structure of the sequences is taken into account. We therefore settle on assessing significance using A10 and A2. In using A2, we follow the lead of work such as Akmaev et al. (9).

Specifically, we evaluate the significance of the observed covariation statistics under the null model designated by A10 and A2. For A2 we need to specify the evolutionary relationships among the sequences, in the form of a phylogenetic tree, and an evolutionary model. The phylogenetic tree is specific to the protein family, i.e., the phycobiliproteins or globins. We used the neighbor-joining method (10) with PAM distances (11), implemented in PHYLIP (12), to estimate the tree for the particular family. The tree was constructed by using sites not in strong motifs. Strong-motif sites were omitted to minimize the bias introduced by simulating from a tree that is estimated by the same features that we later evaluate for statistical significance. For both sample data sets, the reconstructed phylogenies using all sites or only strong-motif sites were similar. We assumed the Dayhoff evolutionary model (11) for changes along a branch. Generation of the tree by the neighbor-joining method and the Dayhoff assumption were made for simplicity. We do not expect our conclusions to be sensitive to these choices for estimating the evolution of the sequences in the absence of selection.

After having specified the phylogenetic tree for the family and an evolutionary model, which assumes no covariation between sites, we studied the behavior of our statistics under the null model using simulations. Following the procedure of Wollenberg and Atchley (13), a complete set of family sequences was generated B = 100,000 times (see below) under these assumptions by using the simulation software PSEQ-GEN (14). That is, the residues at each site were generated by simulating independent and identical evolution, A10, along the tree with evolutionary changes specified by the Dayhoff model, A2. By comparing the observed covariation statistics Mij (4) with those in the simulated data M , b = 1,… ,B, we can test the hypothesis that there is no association between sites i and j. The most stringent rule is to consider the i–j pairs for which Mij is larger than any of the M

, b = 1,… ,B, we can test the hypothesis that there is no association between sites i and j. The most stringent rule is to consider the i–j pairs for which Mij is larger than any of the M . This, in effect, sets the significance level, ε*, of our hypothesis test to 1/(B + 1). By setting the significance level to be very low, we control the number of erroneous covariation declarations.

. This, in effect, sets the significance level, ε*, of our hypothesis test to 1/(B + 1). By setting the significance level to be very low, we control the number of erroneous covariation declarations.

We are restricting the tests to strong-motif pairs within the strong motifs, which corresponds to simultaneously testing K = 347 hypotheses in the phycobiliproteins and K = 232 hypotheses in the globins. To guarantee overall significance for the final number of tests, we use the Bonferroni principle. That is, when we consider site pairs at significance level ε*, the chance that we make a false covariability call for any of the K pairs is Kε*. We shall, in what follows, take B = 105 such that the simultaneous significance level Kε* < 0.01, which corresponds to a true overall significance level of less than 3.47 × 10−3 for the K = 347 hypotheses we shall consider in the phycobiliproteins and 2.32 × 10−3 for the K = 232 hypotheses in the globins.

Data

The first application and more thorough analysis of this method was to the phycobiliproteins. Phycobiliproteins are a family of highly conserved light-harvesting proteins present in prokaryotes (cyanobacteria and some prochlorophytes) and eukaryotes (red algae and cryptomonads). The building block of each of the phycobiliproteins is an αβ heterodimer. In this analysis, we compare 105 amino acid sequences of the α and β subunits of the quantitatively major phycobiliproteins found in cyanobacteria and red algae, allophycocyanin (apcA and apcB), C- and R-phycocyanin (cpcA and cpcB; rpcA and rpcB), phycoerythrocyanin (pecA and pecB), and C-, B-, and R-phycoerythrin (cpeA and cpeB; bpeA and bpeB; and rpeA and rpeB), and cryptomonad biliprotein β subunits (CR-peB) taken from the GenBank and the Swiss-Prot databases (see Table 23, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org; see below). The designations for the sequences given above in parentheses are those used in the databases. The classification, structure, and assembly of the phycobiliproteins, the structures and positions of attachment of their open-chain tetrapyrrole (bilin) prosthetic groups, and the functions of these proteins have been reviewed extensively (15–18). The β subunit of cryptomonad phycobiliproteins is related closely to the β subunits of red algal phycoerythrins (PEs) (19), and sequences of three such polypeptides are included in the analysis.

The analysis was repeated on an alignment of 154 vertebrate globin sequences to examine whether the procedure is generalizable to other examples. The globin family consists of both Mbs and hemoglobins (Hbs), which are responsible for oxygen binding and transport (20, 21). Mb is a monomer with highly compact structure primarily composed of α helices. Attached to the polypeptide is a heme, the prosthetic group to which oxygen binds. Adult Hb contains two αβ heterodimers. Each subunit is structurally similar to Mb. Although the amino acid sequences of the α subunit, β subunit, and Mb are quite different, they have very similar structures (and functions), and therefore it is suitable to apply the procedure to the combined families. Organismal sources and accession numbers are provided in Table 24, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site (see below).

Protein sequences were aligned by using CLUSTALW (22). The alignment was also visually inspected so that known conserved sites were aligned properly. A uniform 190-residue length with a maximum of four gaps allowed alignment of all the phycobiliprotein α and β subunits. The globin sequences were aligned to a uniform length of 161 positions with a maximum of six gaps.

The residue identity and numbering uses the conventional single-letter amino acid abbreviation followed by the residue number in the aligned sequence. For example, an alanine residue in position 4 from the amino terminus is designated A4. The residue numbering is zero-based, although some polypeptide sequences align with no residue in the initial position. Thus, depending on the polypeptide, a residue designated as A4 may be either the fourth or fifth residue from the amino terminus.

Figs. 4–15, Tables 6–42, and accompanying text are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org, and contain the following materials: (i) the locations of strong-motif sites in selected biliprotein and globins; (ii) information on bilin and heme solvent accessibilities after truncation of residues one at a time; (iii) contacts and bonds between side-chain atoms of amino acid residues at strong-motif sites and neighboring atoms; (iv) aligned biliprotein and globin sequences and accession codes; (v) conversion tables for biliprotein and globin residue and bilin/heme numbering; (vi) contact profiles and associated P values for biliproteins and globins; and (vii) the atom type and radii libraries submitted to the web-based GETAREA program for calculation of solvent accessibilities.

Results

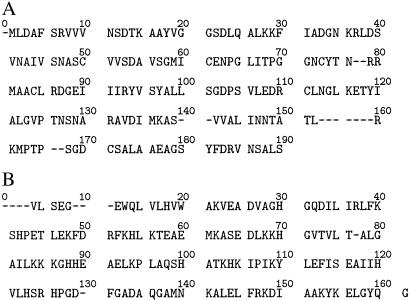

An example of an aligned phycobiliprotein sequence with the residues numbered is shown in Fig. 2A. The full set of aligned sequences is provided in Tables 23 and 24. Before application of the strong-motif search algorithm to the 105 aligned phycobiliprotein sequences, residues common to all sequences were excluded. These universally conserved residues were D13, C84, R86, D87, R93, Y97, G102, and G114. This set of conserved residues is a signature that defines all members of the phycobiliprotein α and β subunit family regardless of the subclass, bilins, or organismal origin. Application of the strong-motif search algorithm to the “edited” sequences identified 35 strong motifs ranging from 2 to 13 residues. In the set of strong motifs, there were K = 347 strong-motif pairs that were checked for covariation. Of these, 10 pairs (containing residues at 12 sites) were found to be covarying statistically at a significance level of 3.47 × 10−3. By our definitions, each site in these pairs is potentially “important” to the molecule. Also, by construction, each site is in at least one strong-motif pair. In this application, all of the 12 sites and their associated residues are contained in pairs within strong motifs corresponding to structural or functional subfamilies as defined by their spectroscopic properties (Table 1).

Fig 2.

An example of an aligned phycobiliprotein sequence from Rhodella violacea PE-β subunit (A) and an aligned Mb sequence from Physeter catodon (sperm whale) (B).

Table 1.

Distribution of the sites selected by our procedure, the important sites, amongst the phycobiliprotein α and β subunit families and the globin families

| Family | Important sites | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phycobiliprotein α and β | ||||||||||||

| AP-α | E15 | V67 | M80 | T81 | T83 | I110 | Y119 | P125 | ||||

| PC-α | T3 | P4 | G80 | K83 | G105 | Y110 | ||||||

| PEC-α | T3 | P4 | G80 | K83 | G105 | Y110 | ||||||

| CPE-α | K83 | G105 | W110 | V118 | Y119 | P125 | ||||||

| BPE-α | K83 | G105 | W110 | V118 | Y119 | P125 | ||||||

| RPE-α | K83 | G105 | W110 | V118 | Y119 | P125 | ||||||

| AP-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| PC-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| PEC-β | D3 | F67 | Q81 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||

| CPE-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| BPE-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| RPE-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| CR-PE-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| Globin | |||||||||||

| Hb-α | L104 | P133 | |||||||||

| Hb-β | W44 | G53 | L104 | H105 | P133 | H155 | |||||

| Mb | E24 | E44 | (L,I,P) 92 | H104 | (I,N,H) 109 | I114 | D149 |

Sites occurring in small strong-motif families (less than four members) within the larger functional subfamilies.

By closely inspecting the structures of representatives of the four phycobiliprotein subfamilies, we explored possible functional roles for these sites. The structures of proteins in each of the four classes [allophycocyanin (AP), phycocyanin (PC), phycoerythrocyanin (PEC), and PE] have been determined by x-ray crystallography, but the structure of a phycobiliprotein–linker complex has only been reported for AP (23–26). Nearest neighbors and specific interactions (hydrogen bonds, electrostatic interactions, etc.) were examined for each site (Supporting Information, Tables 12–22).

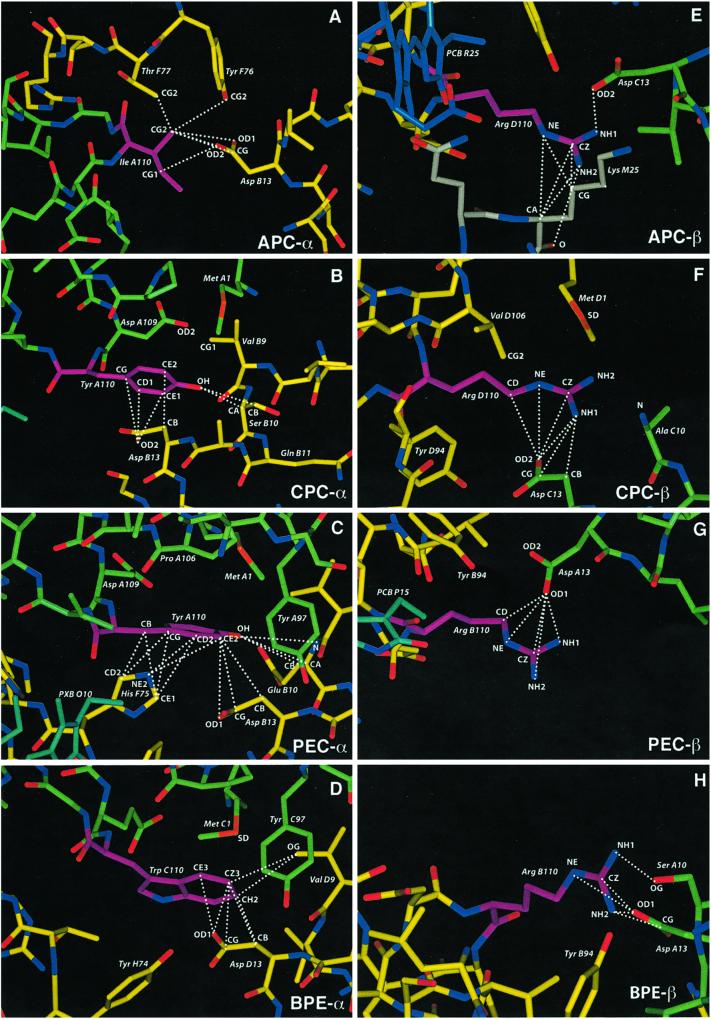

Residues at 5 of the 12 important sites interacted with each other or with one of the residues completely conserved in the aligned phycobiliprotein sequences (see above). D3 in the PC-β and PEC-β subunits are hydrogen-bonded to T3 in the corresponding α subunits. R110, present in all of the β subunits, forms a salt linkage to D13, a conserved residue in all α and β subunits (see Fig. 3). T118, present in all β subunits, forms a hydrogen bond to the main chain carbonyl of G114, a conserved residue in all α and β subunits. Y119, present in all AP, PC, PEC, and PE subunits except PC-α and PEC-α, is hydrogen-bonded to the invariant D87 in all cases except in BPE-α.

Fig 3.

The amino acid environment of residue 110 within biliprotein α and β subunits. (A–D) The 110 residue in α subunits of AP (A), C-PC (B), PEC (C), and B-PE (D). (E–H) The 110 residue in the corresponding β subunits. All bonds and van der Waals contacts with interatomic separations between 2.7 and 4.0 Å are shown as dotted lines; for hydrogen bonds, this is the separation distance between donor and acceptor atoms. Each image is labeled on the lower right with the respective protein and subunit. The residues found at position 110 are particularly noteworthy, because they participate in several strong motifs: Tyr-110 is conserved in all PC and PEC-α subunits, Trp-110 is found in all C-, B-, and R-PE-α subunits, Ile-110 is conserved in all AP-α subunits, and Arg-110 occurs in all biliprotein β subunits. In C (PEC-α), the internal cavity lies behind Tyr-A110; in G (PEC-β), the internal cavity lies below and to the right of Arg-B110; in D (B-PE-α), the internal cavity is behind Trp-C110; and in H (B-PE-β), the internal cavity lies above Arg-B110.

Further examination of the three-dimensional structures revealed that of 56 residues at important sites, 39 (70%) are involved in intersubunit or subunit–linker interactions or in contacts with bilins (Table 2). Overall, 21 (38%) are at or very near interfaces between subunits or interfaces between subunits and linker. In addition, 23 of the residues have contacts to bilins (41%). From calculations of the change in bilin solvent accessibility after truncation of residues one at a time, truncation of residues at 32% of the important sites (M80, G80, T83, K83, A83, T118, Y119, and P125) increased accessibility of solvent to a bilin (Table 3, Supporting Information, and Figs. 10–13). These residues are expected to affect the spectroscopic properties of the proximal bilin through their influence, inter alia, on the polarizability of its environment and conformational mobility in the ground and excited states.

Table 2.

Important residues involved in intersubunit or subunit–linker interactions or contacts to bilins

| AP-α | E15 | V67 | M80 | T81 | T83 | I110 | Y119 | P125 | ||||

| PC-α | T3 | P4 | G80 | K83 | G105 | Y110 | ||||||

| PEC-α | T3 | P4 | G80 | K83 | G105 | Y110 | ||||||

| BPE-α | K83 | G105 | W110 | V118 | Y119 | P125 | ||||||

| AP-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| PC-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| PEC-β | D3 | F67 | Q81 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||

| BPE-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 |

Underlined residues are at or very near interfaces between subunits or interfaces between subunits and linkers. Italicized residues have contacts to bilins. Residues that are both in contact with bilins and at or very near subunit or linker-subunit interfaces are bold.

Table 3.

Inferred consequences of single-residue truncations on accessibility of bilins to solvent

| AP-α | E15 | V67 | M80 | T81 | T83 | I110 | Y119 | P125 | ||||

| PC-α | T3 | P4 | G80 | K83 | G105 | Y110 | ||||||

| PEC-α | T3 | P4 | G80 | K83 | G105 | Y110 | ||||||

| BPE-α | K83 | G105 | W110 | V118 | Y119 | P125 | ||||||

| AP-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| PC-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||||

| PEC-β | D3 | F67 | Q81 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 | |||

| BPE-β | D3 | A83 | S105 | R110 | T118 | Y119 | P125 |

Truncation of bold residues increases accessibility of solvent to a bilin.

For many of the sites, there were no readily interpretable critical interactions with neighboring residues. Nevertheless, it is apparent that the important sites are clustered and not distributed randomly across the surface (Supporting Information, Figs. 4–7). Important sites are located in the interior and near the centrally located β bilin, which serves as the “terminal energy acceptor” (16). Most sites are in key regions for the protein: α/β interfaces, near the linker, or in close proximity to the bilin.

We analyze these features statistically as follows. Define a residue site being in contact if at least one side-chain atom of the residue is within 4 Å of an atom from another subunit, linker, or bilin. The number of contacts and P values for all sites in the α and β subunits in the AP trimer are listed in Table 31. For example, in the AP-α A subunit, residues at 5 of the 8 important sites are in contact with either a subunit interface (one), bilin (two), or at least two such interfaces (two). For the 152 sites not designated as important by our criteria, 26 are in contact with a subunit interface, 11 with a bilin, and 4 with at least two such interfaces. Mainly β subunit residues come in contact with the linker because of the asymmetrical location of the linker in the internal cavity of the AP-(αβ)3–linker complex. The types of contacts for all sites were tallied for each subunit and will be referred to as a contact profile for the subunit (Tables 31–34).

We evaluated the statistical significance of the observed contact profile for each subunit in AP to test whether there was an association between our selection method and sites that are in critical contacts. For all subunits except F, the individual P values from the hypergeometric test were <0.02. By using the Bonferroni principle to control the probability of any incorrect statements for the six tests, the association between the sites designated important by our procedure and the sites in critical interface regions was significant at the 0.05 level for all subunits except C and F. This analysis was repeated on the other three protein structures (Tables 32–34). The results were not significant, but the comparisons are incomplete because contacts to the linker can no longer be observed because of the absence of the linker in these crystallographic structures.

Before the strongly covarying sites were filtered out, this test was also performed on the contact profile of the 12 strong-motif sites in the AP-α subunit and the 22 strong-motif sites in the AP-β subunit. These sites occur in strong motifs that define, with at most one exception, all the AP-α sequences and all the AP-β sequences, respectively. For that list, the P values from the hypergeometric test were all >0.02 except for subunits C and E (Table 37). Accounting for multiple testing up to the 0.05 level, only in subunit E is a statistically significant association detected between the strong-motif sites and the interface sites. Thus, the second cut of sites, based on statistical covariation, is useful for refining the strong-motif site list to find structurally distinguishable positions. This trend was not observed in the other three structures (Tables 38–40), possibly because of the unobservable linker contacts as discussed above.

The analysis was repeated on the 154 globin sequences. An example of an aligned sequence with residues numbered is shown in Fig. 2B. The full set of aligned sequences is provided in Supporting Information (Table 24). Before application of the strong-motif search algorithm, the two conserved residues, L96 and H100, were removed. The algorithm identified 27 strong motifs up to 16 sites long. In the set of strong motifs, there were K = 232 strong-motif pairs that were checked for covariation. According to our procedure, 11 of these pairs were found to be statistically covarying at a significance level of 2.32 × 10−3. In these pairs, there are 11 different sites. They are potentially important sites for the molecule by our definitions. All 11 sites are contained in pairs within strong motifs that correspond to the functional subfamilies or to smaller taxonomic groups contained in the larger functional subfamilies (Table 1).

The crystal structures of human Hb and sperm whale Mb were obtained from the Protein Data Bank database (27, 28). As with the phycobiliproteins, the functional and structural roles could not be explained for all the sites by examining the immediate environment of the site. We again tested for an association between our procedure and the selection of sites that have intersubunit or heme contacts. The number of contacts and P values for each α and β subunit in the Hb-α2β2 tetramer are listed in Table 35, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. The P values for subunits B and D are <0.01. Controlling for overall significance, the association between the sites selected by our procedure and the sites in the critical interface regions was significant at the 0.03 level for subunits B and D. This analysis also was performed on the contact profile of the 18 strong-motif sites in the α subunit and the 16 strong-motif sites in the β subunit (Supporting Information, Table 41). These sites occur in strong motifs that define, with at most one exception, the functional subfamilies or smaller taxonomic groups contained in the functional subfamilies. Now, no subunit exhibits a strong association up to a significance level of 0.3.

For Mb, the P value is 0.07 for testing the association between the important sites and the sites in interface regions (Table 36). Although this would not be considered statistically significant, the P value for the test increases to 0.52 (Table 42) when using all strong-motif sites that define Mb with at most one exception or smaller taxonomic groups contained in the subfamily. So similarly as in the Hbs, filtering the strong-motif sites based on their occurrence in statistically significant associations refined this list of sites with respect to structural features.

Extensive databases provide access to the information on the consequences of many point mutations on the structure and function of the Hb molecule (http://globin.cse.psu.edu/ and www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/). Tables 4 and 5 list the mutations that occur at sites we have identified as important in Hb. Twenty-two point mutations occur at 7 of the 8 important sites. No mutations have been reported at the eighth site, Hb-α P133. Twenty of these mutations affect the structure and/or function of the Hb molecule. The remaining two mutations are predicted on the basis of structure analysis to decrease the stability of the β chain.

Table 4.

Effect of human Hb mutations at important residue sites on the structure and/or function of the Hb molecule

| Hb-α | L104(91) | P133(124) | ||||

| Hb-β | W44(37) | G53(46) | L104(91) | H105(97) | P133(124) | H155(146) |

The residue numbers in parentheses are those used for these residues in the conventional numbering scheme for human Hbs. At residues identified in bold, point mutations affect the structure and/or function of the Hb molecule.

Table 5.

Known mutants

| αLeu91 | Leu91Pro |

| αPro124 | No mutants reported |

| βTrp37 | Trp37Ser, Trp37Arg, Trp37Gly |

| βGly46 | Gly46Arg, Gly46Glu (The predicted effect of these mutations is to decrease the stability of the β chain.) |

| βLeu96 | Leu96Val, Leu96Pro |

| βHis97 | His97Gln, His97Tyr, His97Pro, His97Leu |

| βPro124 | Pro124Arg, Pro124Ser, Pro124Gln, Pro124Leu |

| βHis146 | His146Arg, His146Leu, His146Asp, His146Pro, His146Gln, His146Tyr |

For all sites in both Hb-α and Hb-β, we tallied the number of “normal” and “nonnormal” mutations as defined by an automated search of the word “normal” in the summary page for each mutation in the database referenced above. Differences in the ratio of normal to nonnormal mutations in the important sites versus the sites not designated as important were not significant. This result is not surprising given the small sample sizes involved, particularly in Hb-α where there are only two important sites. Thus, despite a trend in the rate of nonnormal mutations in the important sites and in the percentage of important sites with interface contacts versus this percentage in sites not designated as important, small P values are difficult to attain because of the small absolute size of the set of important sites. However, although the results for some subunits in the contact profile and mutation analyses are not overwhelmingly significant in the statistical sense, these separate analyses provide different sources of evidence, unlinked to the method of selection, all reinforcing the qualitative trend that the important sites differentiate themselves with respect to critical locations in the structure in ways that correspond to what one would expect of functionally important sites.

Discussion

This work is related to other motif-finding and covariation methods, and we will elaborate on the similarities and differences. Local alignments between a query sequence and a database by programs such as BLAST (29) initially look for short stretches of similarities between the pair of sequences and extend them to search for a longer alignment. This is not a motif-finding method per se but can highlight commonalities on a pairwise level between family sequences.

Programs such as MEME (5) and PRATT (30) successively extract groups of sites of interest appearing in large subsets of sequences from a collection of unaligned sequences without a query. This method produces a local alignment in the form of an ungapped position-dependent residue frequency matrix in MEME or a regular expression with preconstrained length in PRATT. Such methods are useful when the signal in a set of related sequences is too weak for global multiple alignment methods. A common feature of these methods is that the patterns pointed out are constrained to a short region of sites. In MEME, the sites appearing in the motif are consecutive. This is perhaps unavoidable in unaligned sequences without further information. The sites in the motifs discovered by these methods are also of interest, because the motif likely corresponds to a region of activity such as a structural domain. In contrast, the strong-motif algorithm is based on an alignment, and thus sites are not restricted to be consecutive or within a certain bounded region but require a family to be alignable (i.e., adequate degree of homology between the sequences).

Programs such as EMOTIF (6) extract the most representative motifs, based on a particular measure, appearing in large subfamilies of aligned sequences. These motifs may involve a group of sites dispersed throughout the sequence. For families of even modest size, such enumeration-type motif-finding methods yield enormously large numbers of patterns. The statistical significance associated with such patterns is usually unclear, because the search process is not usually taken into account. Similarly, the strong-motif algorithm enumerates patterns but identifies all patterns of sites that covary in the most extreme fashion possible and uniquely identify the subfamilies in which they are conserved. In our example data, we found that the number of patterns discovered by this algorithm is fairly moderate, such that all strong motifs and strong-motif families can be examined individually.

Many methods have been developed to explore the relationship between two neighboring sites in the three-dimensional structure of the protein and the degree of association between the two positions in the alignment (31–34). The reasoning is that if two sites are interacting or in close contact with each other, then the evolution of one site over time should affect the evolution of the other site (for an excellent actual example, see ref. 35). In earlier work, statistical significance was assessed assuming that the sequences were independent (under A20). Later research incorporated the phylogenetic relationships between the sequences, our A2, for more realistic evaluations (33, 34).

To evaluate their performance, most methods have focused on population behavior. Pairs of sites that are “strongly” covarying are generally closer in three-dimensional space than the “weakly” covarying pairs. This research has shown that some correlation between distance and the covariation measures exists for pairs, but it is weak (33). We also found this to be true in our applications. However, in our method the purpose of statistical association is not to relate it directly to the physical distance between sites but as an interesting sequence feature that distinguishes sites.

The phycobiliprotein family of AP, PC, PEC, and PE polypeptides was chosen for the first application of the strong-motif search algorithm because there is high homology between the amino acid sequences of these proteins, and many sequences of each class of phycobiliprotein have been reported. The structures and sites of covalent attachment of the bilin prosthetic groups are known. The three-dimensional structures of representatives of all four classes have been determined at high resolution and show strong overall similarity (23–26, 36). The αβ building blocks of all four proteins form higher order assemblies, (αβ)3 and (αβ)6, with similar quaternary structures. Finally, these proteins occur in both prokaryotic organisms (cyanobacteria) and eukaryotes (red algae and the cryptomonads). Organisms classified morphologically as red algae appear in the fossil record between 1 and 1.3 billion years ago (37). Because the phycobiliproteins of cyanobacteria and of red algal chloroplasts share common ancestry, the ancestral phycobiliproteins antedate the appearance of red algae in the fossil record. The phycobiliprotein α-type and β-type subunits can be readily distinguished based on amino acid sequence and bilin type and number. They can be subdivided further on the basis of organismal origin. The groupings produced by this approach correspond extremely well with those based on the distribution of strong motifs. In particular, distinctive combinations of 21 of the 35 motifs segregate precisely with previously assigned groupings: PE-α and PE-β, PEC-α and PEC-β, PC-α and PC-β, and AP-α and AP-β (15–18).

It is reasonable to suppose that each of the strong motifs in the phycobiliproteins possibly defines residues of critical importance to the members of the cluster of proteins in which it occurs. Nevertheless, it is also very possible that many strong motifs are accidental—a byproduct of a shared evolutionary past. From the point of view of the neutral theory of evolution (38), we are interested in separating out the structurally and functionally important positions from the selectively neutral positions.

We use features between sites as the next criterion to distinguish the sites. A large degree of statistical covariation may be an important signal for some sort of activity at these sites, although the manner in which they affect each other or how they are similarly affected cannot be deduced. We evaluate whether the strength of the association between the sites would still exist if the phylogeny is accounted for. It is also very possible that sites filtered out by this procedure are important to the molecule. By using stringent statistical cutoffs, we ensure that the selected sites distinguish themselves from the rest according to our criteria, but we do not claim that they are the only ones of any interest.

As documented in Results, in the structural analysis our selected sites differentiate themselves with respect to their preferential locations at intersubunit contacts, interactions with completely conserved residues, or with each other and interactions with prosthetic groups. In human Hb, inherited mutations that occur at the selected sites are deleterious to structure and function of the molecule. More comprehensive evaluations, such as site-specific mutagenesis studies, are beyond the scope of this article. In light of our results, we propose this method as a means of identifying candidate sites for such experiments.

I.

As in Bickel et al. (4), form for each pair of sites i1,i2 an m1 × m2 contingency table, where m1 is the number of amino acid residues appearing in the family F at site i1 and m2 that appear at site i2. The cell corresponding to amino acid j1 at i1 and j2 at i2 has as entry the number of sequences in F having (i1,j1),(i2,j2). Then any cell having s as an entry and 0 appearing in all other cells in its row and column corresponds to a strong motif {(i1,j1),(i2,j2)} for the s sequences counted in that cell.

II.

List all couples of S-R pairs corresponding to cells with s appearing in them and 0s in all other cells in the same row and column.

III.

For the given s, define an equivalence relation between S-R pairs (i1,j1) and (i2,j2), i1 ≠ i2 by (i1,j1) ≡ (i2,j2) iff {(i1,j1),(i2,j2)} appears in the list developed in II.

IV.

This equivalence relation partitions the set of all S-R pairs into disjoint sets S1, … , St. List all sequences corresponding to any member of Sk and call it Fk, 1 ≤ k ≤ t. It is a consequence of the construction that all equivalent S-R pairs yield the same set of sequences Fk. Each Fk is of cardinality s, and Sk is precisely the strong motif of Fk. This algorithm repeated for s = 1, … , n yields all strong motifs of length ≥2 and the corresponding subfamilies.

Note that determining all the Sk and Fk for each s takes on the order of n( ) ≍ nL2 operations. Doing this for s = 1, … , n thus takes on the order of n2L2 operations.

) ≍ nL2 operations. Doing this for s = 1, … , n thus takes on the order of n2L2 operations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Robert Huber for providing coordinates for the structures of the B-PEs from Porphyridium cruentum and Porphyridium sordidum as well as the phycoerythrocyanin (PEC) from Mastigocladus laminosus. We thank Sunil Aggarwal for help with assembling sequence data, Herman Chernoff for many helpful remarks and questions, and Eric Lander and an anonymous referee for making us relate our work to phylogeny. We also thank the Molecular Graphics Laboratory in the Department of Chemistry (University of California, Berkeley) for the use of its computers. This work was supported by grants from the Lucille P. Markey Charitable Trust (to A.N.G.) and the W. M. Keck Foundation (to A.N.G.). Research was partially supported by National Science Foundation Grant DMS 9802960 (to P.J.B.) and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (to K.J.K.).

Abbreviations

Mb, myoglobin

S-R, site-residue

AP, allophycocyanin

PC, phycocyanin

PE, phycoerythrin

PEC, phycoerythrocyanin

This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected on May 1, 2001.

We are indebted to the referee of a previous version of this paper for pointing out that our notion of strong motif is related to the notion of “compatibility” of characters in cladistics introduced by LeQuesne in 1969 (39) and Estabrook et al. (40). For the simplest case when two characters (sites) each have only two possible values (residues), compatibility corresponds to the requirement that in the 2 × 2 table formed from these sites in the manner indicated above at least one cell have entry 0. This is weaker than our requirement that only the two diagonal or antidiagonal cells be nonzero. For more than two states, compatibility corresponds to the possibility of using the two characters in the construction of an evolutionary tree in which neither character can mutate back. The problem of finding the largest sets of compatible characters (maximal cliques) is believed to be non-polynomial (NP) hard as opposed to our O(n2L2) problem.

References

- 1.Page R. D. M. & Holmes, E. C., (1998) Molecular Evolution: A Phylogenetic Approach (Blackwell, Oxford), pp. 228–279.

- 2.Lockless S. W. & Ranganathan, R. (1999) Science 286, 295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manning J. M., Dumoulin, A., Manning, L. R., Chen, W., Padovan, J. C., Chait, B. T. & Popowicz, A. (1999) Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 211-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickel P. J., Cosman, P. C., Olshen, R. A., Spector, P. C., Rodrigo, A. G. & Mullins, J. T. (1996) AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 12, 1401-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey T. L. & Elkan, C. (1995) Mach. Learn. 21, 51-83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nevill-Manning C. G., Wu, T. D. & Brutlag, D. L. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 118-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stormo G. D. & Hartzell, G. W. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 1183-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence C. E. & Reilly, A. W. (1990) Proteins 7, 41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akmaev V. R., Kelley, S. T. & Stormo, G. D. (2000) Bioinformatics 16, 501-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saitou N. & Nei, M. (1987) Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayhoff M. O., Schwartz, R. M. & Orcutt, B. C. (1978) in Atlas of Protein Sequence and Structure, ed. Dayhoff, M. O. (Natl. Biomed. Res. Found., Washington, DC), Vol. 5, Suppl. 3, pp. 345–352. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenstein J. (1989) Cladistics 5, 164-166. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wollenberg K. R. & Atchley, W. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 3288-3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grassly N., Adachi, J. & Rambaut, A. (1997) Comput. Appl. Biosci. 13, 559-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glazer A. N. (1985) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 14, 47-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glazer A. N. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glazer A. N. (1994) in Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology, eds. Bittar, E. E. & Barber, J. (Jai, Greenwich, CT), pp. 119–149.

- 18.Sidler W. A. (1994) in The Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria, ed. Bryant, D. A. (Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands), pp. 139–216.

- 19.Glazer A. N. & Wedemayer, G. J. (1995) Photosynth. Res. 46, 93-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fermi G. & Perutz, M. F. (1981) in Atlas of Molecular Structures in Biology, eds. Phillips, D. C & Richards, F. M. (Clarendon, Oxford).

- 21.Dickerson R. E. & Geis, I., (1983) Hemoglobin: Structure, Function, Evolution, and Pathology (Benjamin/Cummings, Menlo Park, CA).

- 22.Thompson J. D., Higgens, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reuter W., Wiegand, G., Huber, R. & Than, M. E. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1363-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duerring M., Schmidt, G. B. & Huber, R. (1991) J. Mol. Biol. 217, 577-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rümbeli R., Schirmer, T., Bode, W., Sidler, W. & Zuber, H. (1985) J. Mol. Biol. 186, 197-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ficner R. & Huber, R. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 218, 103-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takano T. (1984) in Methods and Applications in Crystallographic Computing, eds. Hall, S. R. & Ashida, T. (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford), pp. 262.

- 28.Tame J. & Vallone, B. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. D 56, 805-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altschul S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. (1990) J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonassen I., Collins, J. F. & Higgins, D. G. (1995) Protein Sci. 4, 1587-1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altschuh D., Lesk, A. M., Bloomer, A. C. & Klug, A. (1987) J. Mol. Biol. 193, 693-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neher E. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 98-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shindyalov I. N., Kolchanov, N. A. & Sander, C. (1994) Protein Eng. 7, 349-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollock D. D., Taylor, W. R. & Goldman, N. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 287, 187-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J. & Rosenberg, H. F. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5486-5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilk K. E., Harrop, S. J., Jankova, L., Edler, D., Keenan, G., Sharples, F., Hiller, R. G. & Curmi, P. M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8901-8906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schopf J. W. (1978) Sci. Am. 239, 111-138. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimura M. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 3440-3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LeQuesne W. J. (1982) Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 74, 267-275. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Estabrook G. F., Johnson, C. S., Jr. & McMorris, F. R. (1976) Math. Biosci. 29, 181-187. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.