Abstract

Heme, a major functional form of iron in the cell, is synthesized in the mitochondria by ferrochelatase inserting ferrous iron into protoporphyrin IX. Heme deficiency was induced with N-methylprotoporphyrin IX, a selective inhibitor of ferrochelatase, in two human brain cell lines, SHSY5Y (neuroblastoma) and U373 (astrocytoma), as well as in rat primary hippocampal neurons. Heme deficiency in brain cells decreases mitochondrial complex IV, activates nitric oxide synthase, alters amyloid precursor protein, and corrupts iron and zinc homeostasis. The metabolic consequences resulting from heme deficiency seem similar to dysfunctional neurons in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Heme-deficient SHSY5Y or U373 cells die when induced to differentiate or to proliferate, respectively. The role of heme in these observations could result from its interaction with heme regulatory motifs in specific proteins or secondary to the compromised mitochondria. Common causes of heme deficiency include aging, deficiency of iron and vitamin B6, and exposure to toxic metals such as aluminum. Iron and B6 deficiencies are especially important because they are widespread, but they are also preventable with supplementation. Thus, heme deficiency or dysregulation may be an important and preventable component of the neurodegenerative process.

Keywords: iron, complex IV, amyloid precursor protein (APP), nitric oxide synthase, oxidative stress

The causes that underlie the neurodegeneration accompanying Alzheimer's disease (AD) are unknown. Normal aging of the brain and the pathology of the neurodegeneration caused by AD share: the decline in complex IV (1), mitochondrial dysfunction (2), hypometabolism (3, 4), oxidative stress (5), loss of iron homeostasis (6), and dystrophic neurons. Several mutations causing altered proteins amyloid precursor protein (APP), PS1, and PS2 have been identified in familial cases of AD. Aging is a risk factor even in these familial cases, which represent a small portion of the total cases of AD.

Heme synthesis declines with age (7). This decline could explain the age-associated loss of iron homeostasis, because insufficient levels of heme would compromise iron regulation and vice versa (8). Furthermore, we demonstrated that heme deficiency shows a selective decrease in mitochondrial complex IV that leads to oxidative stress and corruption of Ca2+ homeostasis (9). Heme functions in hemoglobin and enzymes, and it regulates the activity of proteins and gene expression through the heme regulatory motifs (HRMs) in several proteins (10–12). Also, a role of heme in promoting neurite outgrowth and neurogenesis has been known for some time (13). Thus, dysfunctional heme metabolism could alter gene expression in brain cells, perhaps even preceding altered cytochrome activity.

Heme synthetic pathway depends on essential micronutrients, such as vitamin B6, lipoic acid, iron, copper, and zinc (8). About 10% of the U.S. population ingest <50% of the recommended daily allowance (RDA) for B6 (14); ≈25% of menstruating women in the U.S. ingest <50% of the RDA for iron. Iron deficiency is the most common micronutrient deficiency in the world in menstruating women and in children (14). In addition, heme synthesis is susceptible to exogenous lead, aluminum, and other environmental toxins (15, 16). Ferrochelatase is inactivated when its iron-sulfur cluster disassembles because intracellular iron levels are low (17) or nitric oxide (NO) is present (18). Iron deficiency is by far the most studied; it impairs cognitive function in children, impacts the morphology and the physiology of brain even before changes in hemoglobin appear (19), damages mitochondria (20), and causes oxidative stress (20). Iron deficiency in children is associated with difficulties in performing cognitive tasks and retardation in the development of the CNS (21, 22). Prenatal iron deficiency causes loss of cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) in selected regions in the brain of rats (23) and causes a decrease in ferrochelatase (17). Iron deficiency also occurs in the elderly (24), but surprisingly little work has been reported concerning heme and iron deficiency in brain dysfunction with age. The increase in the levels of iron with age could occur as a result of the inefficient synthesis of heme, suggesting a functional deficiency of iron in advanced age (8).

In this study we tested the hypothesis of a possible role of heme deficiency in neuronal decay. We found that heme deficiency changes mitochondrial complex IV, APP, NO synthase (NOS), and zinc and iron homeostasis. Many of the phenotypic changes seen in heme-deficient cells are also seen in the aging brain and are even more pronounced in neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD. In addition, brain cells that were heme-deficient failed to differentiate or to complete a successful cell cycle, which suggests a unique function of heme that is beyond the classic perception of heme in cell biology.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

N-methylprotoporphyrin (NMP) was from Porphyrin Products (Logan, UT). Anti-human cytochrome c oxidase subunit II mouse monoclonal antibody (12c4-f12) was from Molecular Probes; anti-human APP (preA4695) mouse monoclonal antibody against the N terminus (MAB348 clone 22C11) was from Chemicon; anti-neuronal NOS (NOS1) rabbit-polyclonal antibody against the C terminus (R-20) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide, thymidine, laminin, and poly-d-lysine were from Sigma. Cell media (DMEM), nerve growth factor, nonessential amino acids, and sodium pyruvate were from Invitrogen. The reagents for SDS/PAGE and Western blotting were of the highest grade available.

Tissue Cultures.

Human neuroblastoma (SHSY5Y) and astrocytoma (U373) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained as described by the supplier. In brief, the cells were split two times every week (except SHSY5Y were split on a weekly basis) by trypsin/EDTA and seeded as 1:10 (U373) or 1:5 (SHSY5Y) dilutions. The cells were maintained in DMEM/1% non-essential amino acids/1% sodium pyruvate at 37°C in a 5% CO2/95% air-equilibrated incubator.

Preparation of Hippocampal Neurons.

Children's Hospital's Animal Care and Use Committee approved the animal experimentation performed in this study. Hippocampal primary neurons were prepared by using 12-h-old neonatal Fischer 344 rats according to the published protocol (25).

Inhibition of Heme Synthesis.

N-methylprotoporphyrin IX (NMP) mimics protoporphyrin IX, the substrate for ferrochelatase, except that a methyl group is added to one of its nitrogens. NMP binds ferrochelatase with affinity similar to protoporphyrin IX, but the methyl group prevents iron from being inserted into NMP (26); thus, it is a selective and specific inhibitor for ferrochelatase (27). NMP has been used previously in several studies to inhibit heme synthesis (9, 28). Cells treated with NMP are still able to synthesize heme up to 40% of the controls (29) by up-regulating ferrochelatase (9). To induce heme deficiency, NMP was applied at concentrations and intervals as stated in figure legends.

Immuno (Western) blotting with SDS/10–12% polyacrylamide gel, poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes, and specific antibodies against the selected proteins was applied to evaluate the effect of NMP on complex IV, NOS, and APP.

Production of Nitrate/Nitrite as a Measure for NOS Activity.

The level of nitrate/nitrite produced by the cells was measured in the medium by Griess Reagents by using a nitrate/nitrite colorimetric assay kit from Alexis Biochemicals (Carlsbad, CA).

Quantification of Cellular Metal Content.

Iron and zinc content was determined by inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (IRIS 5900, Thermo Elemental, Franklin, MA) by using the protocol from a previous report (30). Metal content was expressed as average values from two to five wavelengths per sample with each sample run in triplicate. Values were normalized to cell number determined in triplicate by using a Z2 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter).

Induction of Cell Differentiation in Neuroblastoma and Proliferation in Astrocytoma.

Differentiation of SHSY5Y was induced by DMEM + 50 ng/ml nerve growth factor and thymidine (31). Differentiation is completed within 2–3 h and evaluated by the axon growth out of the cell body (13). Undifferentiated SHSY5Y cells, both heme-deficient and heme-sufficient, were maintained in complete medium. U373 were induced to proliferate by replacing week-old medium with a fresh medium, which is supplemented with 10% or 20% serum, to induce proliferation by the growth factors in the serum (32).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis, using Student's two-tailed t test, ANOVA, or nonparametric Mann–Whitney test, was performed with an INSTAT statistical analysis (Instat, San Diego) or PRISM (GraphPad, San Diego). Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Complex IV Is Corrupted as Brain Cells Become Heme-Deficient.

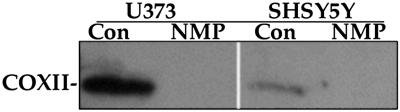

The decline in mitochondrial subunit II (COXII) of complex IV was used to assess the status of complex IV. Brain cells lose complex IV after induction of heme deficiency by 10 μM NMP (Fig. 1). Similar results were demonstrated in human normal fibroblasts (9). Heme deficiency also selectively decreases complex IV in rat primary hippocampal neurons (data not shown). Although heme-deficient neuroblastoma and astrocytoma cells exhibited normal morphology with no sign of toxicity, the primary neurons did not tolerate heme deficiency and died after 48 h (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Heme deficiency selectively prevents assembly of cytochrome c oxidase. Human neuroblastoma (SHSY5Y) and astrocytoma (U373) cells were maintained for 6 days with a medium ± 10 μM NMP. After that the proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE (12%), Western blotted, and analyzed by monoclonal antibodies for subunit II of complex IV. The data presented are from one representative experiment of at least three independent experiments. Con, control; COXII, subunit II of complex IV.

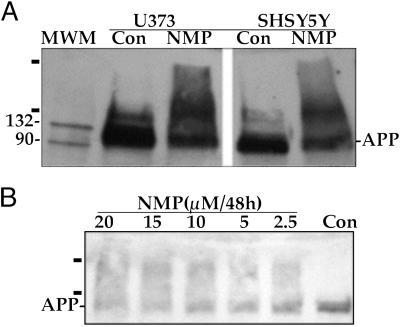

Heme Deficiency Alters Endogenous APP.

We examined the effect of heme deficiency on APP. Monomeric APP decreases in brain cells after 5 days of heme deficiency to ≈50% of the controls, whereas a dimeric and higher molecular mass species (≥200 kDa) appears as detected by antibody specific for APP (Fig. 2A). APP in hippocampal primary neurons was similarly altered by heme deficiency (Fig. 2B).

Fig 2.

Heme deficiency induces dimers and aggregates of APP in human brain cells and in rat hippocampal primary neurons. (A) Human brain cells (SHSY5Y and U373). (B) Rat hippocampal primary neurons. After induction of heme deficiency (A, 10 μM NMP for 6 days or B, different concentrations of NMP) the cells were harvested, and proteins were separated on SDS/PAGE, Western blotted, and analyzed by specific antibody for APP. The bars label APP aggregates. The data are from one of six independent experiments (human brain cells) and three experiments of hippocampal primary neurons. MWM, molecular weight markers.

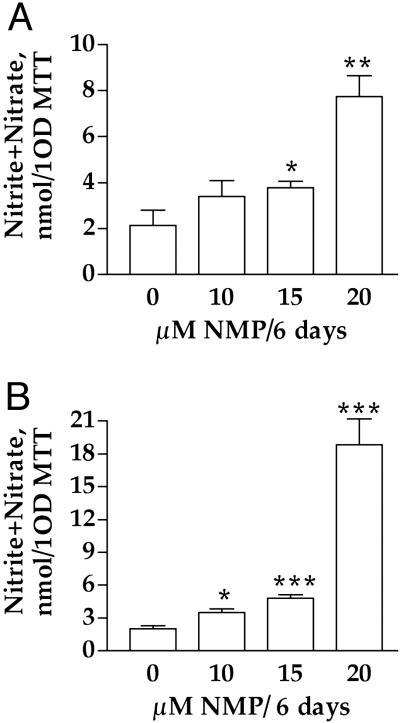

NOS Is Up-Regulated in Heme-Deficient Cells.

Heme deficiency is associated with an increase in the activity of NOS in SHSY5Y (Fig. 3A) and U373 (Fig. 3B). The activity of NOS was determined by measuring the levels of nitrite and nitrate that were released to the medium. The level of nitrite and nitrate are normalized to the ability of the cells to reduce 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT). A similar increase in NOS activity was observed when the results were normalized to protein (data not shown). Heme deficiency also induced a similar increase in NOS activity in primary rat hippocampal neurons (data not shown).

Fig 3.

Heme deficiency induces NOS1 in human brain cells. Heme deficiency was induced by incubation with 10 μM NMP for 6 days. The medium of heme-deficient and control cells was tested for the level of nitrite/nitrate as a measure for NOS1 activity. The data of NOS activity were normalized to 1 OD at 585 nm produced by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. (A) SHSY5Y. (B) U373. The data are a mean ± SD of one experiment of four. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

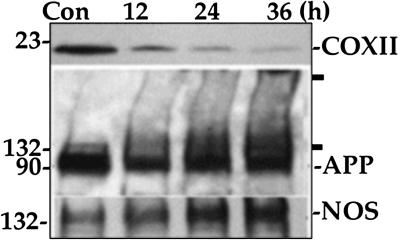

Kinetics of Loss of Complex IV, Alteration in APP, and Up-Regulation of NOS in Response to Heme Deficiency.

Substantial change to complex IV, APP, and NOS occurs even at 12 h of heme deficiency (Fig. 4, data from U373). The relative change of each protein after 12 h as compared with the control was as follows: complex IV 74% decrease, NOS 23% increase, and APP 40% decrease. The decrease in APP was associated with formation of aggregates that appeared as dimers and higher molecular weight forms. Complex IV seems to be the most affected protein, followed by induction of NOS and changes to APP. These trends continued through the duration of heme deficiency.

Fig 4.

Complex IV is the first to decrease in heme-deficient human brain cells. Heme deficiency was induced by incubation with 10 μM NMP. The cells were harvested and prepared for analysis at different intervals. The level of COXII (subunit II of complex IV), NOS, and APP were evaluated by SDS/PAGE followed by Western blotting. The data are from one of three independent experiments with U373 cells.

Heme Deficiency Alters Metal Homeostasis in Astrocytoma (U373) but Not in Neuroblastoma (SHSY5Y).

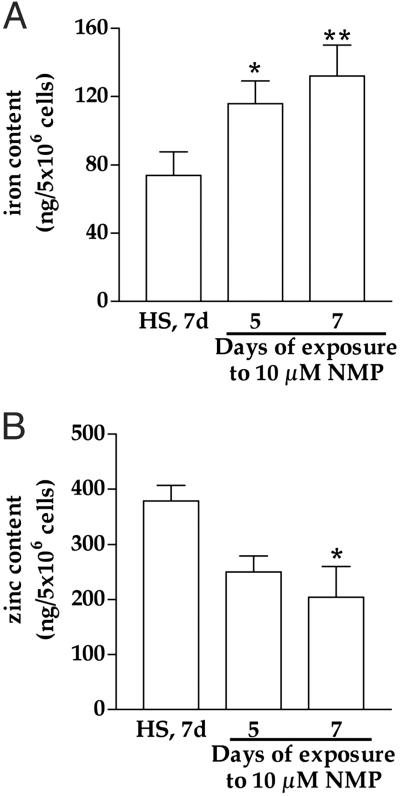

A 1.6-fold increase in iron in U373 cells was seen in response to 7 days of heme deficiency (Fig. 5A). The level of iron in SHSY5Y was not influenced by heme deficiency: heme-sufficient = 59.8 ± 13.2 ng of iron per 5 × 106 cells; heme-deficient = 64 ± 16.5 ng of iron per 5 × 106 cells (mean ± SEM, n = 3). Furthermore, zinc decreases by ≈50% in U373 (Fig. 5B), whereas the level of zinc in SHSY5Y was not influenced by heme deficiency: heme-sufficient = 91 ± 6.7 ng of zinc per 5 × 106 cells; heme-deficient = 126 ± 26.7 ng of zinc per 5 × 106 cells (mean ± SEM, n = 3). We measured the level of iron in the concentrated NMP stock to rule out the possibility that NMP adds iron to the cells, but no iron was detectable (data not shown). We were not able to measure iron and zinc in primary hippocampal neurons from rats because of limited cell number.

Fig 5.

Heme deficiency increases iron and decreases zinc in human astrocytoma (U373). The level of intracellular iron (A) and zinc (B) in heme-deficient cells was evaluated by inductively coupled plasma spectrometry and compared with heme-sufficient (control) cells maintained for 7 days in culture conditions. The data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. HS, heme-sufficient (control); d, days.

Heme Deficiency Compromises Proliferation or Differentiation of Astrocytoma (U373) or Neuroblastoma (SHSY5Y).

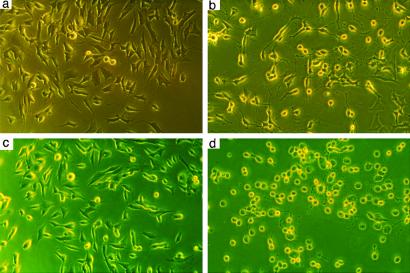

The undifferentiated cells, both heme-sufficient and -deficient, were maintained in complete medium (Fig. 6 a and c). Differentiation of heme-sufficient SHSY5Y was successfully completed by DMEM supplemented with 50 ng of nerve growth factor per ml and thymidine (Fig. 6b). The differentiation became obvious after 3–4 h and the neurons remained viable for 3 days. Differentiation of heme-deficient SHSY5Y failed as the axons degenerated and all of the cells died within 24 h (Fig. 6d).

Fig 6.

Heme deficiency compromises differentiation in human neuroblastoma. Heme deficiency was induced by incubation with 10 μM NMP for 5 days. The differentiation of SHSY5Y was induced by DMEM + 50 ng/ml nerve growth factor. Heme-sufficient (a) and heme-deficient (c) cells seemed completely normal before the differentiation. Heme-sufficient cells differentiated to neurons (b) as expected within 3 h, whereas heme-deficient cells failed to complete the differentiation, lost their axons, and died within 3–4 h after differentiation (d). Shown is one representative experiment of four.

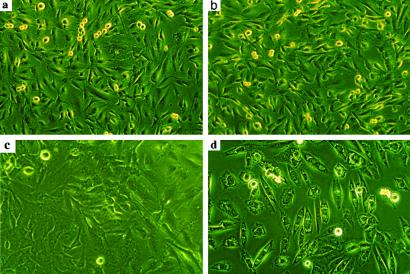

Serum is a source of growth factors that increase the number of cells that enter the cell cycle. Resting heme-sufficient or -deficient cells in a week-old medium seem normal with no signs of stress or toxicity as evaluated by examining the external morphology of the cells (Fig. 7 a and c). When the used medium was replaced with fresh medium that contains 10% serum, all of the heme-deficient cells died within 7 h (Fig. 7d), whereas the heme-sufficient cells (Fig. 7b) were normal.

Fig 7.

Heme deficiency compromises proliferation in human astrocytoma. Heme deficiency was induced as described in Fig. 6 in U373 cells. The cells were induced to proliferate by replacing the week-old medium with fresh complete medium. Heme-sufficient (a) and heme-deficient (c) cells seemed completely normal before the old medium was replaced by the fresh medium. Heme-sufficient cells were not affected by the fresh medium (b), whereas heme deficiency impaired cellular response to serum in heme-deficient cells (d) and the cells died within 7 h. Shown is one representative experiment of four.

Discussion

Heme deficiency leads to impaired energy production by corrupting complex IV, apparently because of shortage in heme-a (9), causing mitochondrial decay, oxidative stress, and oxidative damage (9) (Fig. 1). Our research on metabolism of heme suggests an association between inadequate levels of heme, loss of mitochondrial quality, and the aging process, including neurodegeneration (Table 1). Thus, adequate levels of heme seem to be essential for sustaining normal levels of complex IV, high quality of mitochondria (9), and signaling pathways.

Table 1.

Similarity between the consequences of heme deficiency and normal aging/neurodegeneration

| Factor in study | Heme deficiency | Aging/neurodegeneration |

|---|---|---|

| Complex IV | Loss of complex IV (9) | Loss of complex IV (1) |

| Iron | Accumulation (Fig. 5A) | Accumulation (6) |

| Oxidative stress | Increased (9) | Increased (5) |

| APP | Decreased and aggregates appear (Fig. 2) | Dimer or aggregate (41) |

| NOS | Increased (Fig. 3) | Increased (55) |

| Cell cycle and differentiation | Disabled differentiation or proliferation (Figs. 6 and 7) | Loss of axons; neuronal death (5) |

| Metabolism | Mitochondrial decline (9) | Hypometabolism (3, 4) |

| Metabolism of Ca2+ | Corrupted (9) | Corrupted (34) |

| Ferrochelatase | Increased (9) | Increased in senescent cells (9) |

| Heme synthesis | Decreased | Decreased with age (7) |

Not determined in vivo.

Not determined in the aging brain.

The metabolic events that initiate mitochondrial decay, neuronal death, and the neurodegeneration caused by AD (2, 33) are unknown. Abnormal neuronal signal transduction pathways may play a role in neurodegeneration (34). Additionally, oxidative stress is likely to be an important factor during neurodegeneration (reviewed in ref. 35), yet the causes of any of these are still not clear.

We find that components of some signal transduction pathways are altered during heme deficiency. Heme-deficient cells make abnormal forms of APP (Fig. 2), which is processed to amyloid-β, a hallmark peptide in the pathology of AD (reviewed in ref. 36). APP is a type 1 plasma membrane receptor and seems to function in signal transduction pathways, neuronal differentiation, cell cycling, and metal homeostasis (37–40). The data shown in this study clearly demonstrate that heme plays a role in the cell biology of APP (Fig. 2), in metal homeostasis (Fig. 5), and in the cell cycle and differentiation (Figs. 6 and 7). Dimers and aggregates of APP and Aβ1–42 (or Aβ1–40) have been demonstrated in brain cells (41, 42). APP dimers and aggregates induced by heme deficiency are likely to be the abnormal forms of APP.

Complex IV seems to be the most sensitive to heme deficiency (Fig. 4), which leads to mitochondrial decay, suggesting the decay of mitochondria triggers events that alter the cell biology of APP, NOS, and neurons and astrocytes (Figs. 6 and 7). It is not clear why APP aggregates in heme-deficient cells. Selective oxidative damage to APP that creates dimers may be the mechanism, although classic antioxidants (vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine) could not prevent this aggregation (data not shown). APP aggregates were detectable in the cell pellet even under reducing conditions, suggesting that thiol-disulfides probably play little role in this aggregation. APP is capable of binding copper and iron in redox-active forms able to catalyze the Fenton reaction (43, 44); iron was shown to increase in heme-deficient cells, whereas intracellular zinc decreased (Fig. 5). Zinc is known for its ability to block iron-mediated production of free radicals by serving as antioxidant (45). Cross-linking of APP, mediated by iron or copper, is a possible explanation for the dimers of APP. Susceptibility of APP to oxidative damage has been demonstrated (46). Thus, heme deficiency would be a metabolic disorder that initiates oxidative stress and may alter signal transduction pathways.

Iron accumulates in cells (47), and a marked increase in zinc and iron associated with extracellular plaques is found in AD patients, suggesting a disruption of metal homeostasis (48). Heme-deficient astrocytoma cells (and IMR90 cells, data not shown) accumulate iron (Fig. 5A), probably in the mitochondria because corruption of heme synthesis causes iron to accumulate in this organelle (reviewed in ref. 8). Iron accumulation and a decrease in intracellular zinc in the brain and other tissues is also a feature of aging and age-associated neurodegeneration (49). Zinc supplementation has been reported to improve the cognition of AD patients (50). To understand the mechanisms leading to the loss of iron homeostasis with age, changes in the biochemical pathways that assimilate iron to heme or to iron–sulfur clusters should be studied (discussed in ref. 8). In most of the disorders or mutations that affect the synthesis of heme, or iron–sulfur clusters, iron homeostasis is lost and iron subsequently accumulates in the mitochondria, emphasizing the role of mitochondria in intracellular iron homeostasis (8, 51). The primary causes for defective iron homeostasis with age and for its consequences on zinc homeostasis are still obscure. Reduced bioavailability of intracellular iron for heme synthesis may contribute to the loss of iron homeostasis, which may result in iron accumulation with age. In addition, iron acquisition by the cells is increased by oxidants that activate iron-regulatory protein 1 (IRP1) (52) and by low heme, which stabilizes IRP2 (53); both may contribute to increased iron influx to the cells through the normal mechanism of iron uptake. Two other inhibitors of heme synthesis, succinylacetone and isoniazid, stimulate iron uptake through the transferrin receptor (54). In our model of heme deficiency, iron is the last parameter to change, which is consistent with the hypothesis that alteration in heme metabolism is the driving force for iron to accumulate in the cell.

Heme deficiency induces NOS (a heme protein) 2- to 3-fold in neuronal cells and 7-fold in astrocytes. As a result, high levels of nitrate/nitrites were found in the medium, suggesting elevated production of reactive nitrogen species consistent with the oxidative stress demonstrated (9). Nitrotyrosine accumulates in brain proteins in an age-associated manner and during neurodegeneration (55). Among the heme proteins studied, only complex IV and NOS levels were changed in heme deficiency, yet as complex IV decreases, NOS increases. The unexpected increase in NOS and production of nitric oxide (NO•) may reflect an increase of the cytosolic Ca2+, which is associated with up-regulation of NOS, although other mechanisms that drive up-regulation of NOS are possible. The reduced level of complex IV increases the local concentration of molecular oxygen in the cell, and leaves the mitochondrial electron-transport chain more reduced, which would lead to an increase in the ratios of NADH/NAD and NADPH/NADP in the mitochondria as a result of the decrease in the activity of mitochondrial electron-transport complexes. Thus, it could be that NOS activity increases in heme-deficient cells as a physiological response to remove excess molecular oxygen and to regenerate NAD/NADP, because NOS uses NADPH as a cofactor. Alternatively, increased production of NO• could be an attempt of the cells to quench superoxide radical as protective or signaling mechanism. A role for mitochondrial NOS in the increase in NO• production in heme-deficient cells is possible. The opposing changes in NOS and complex IV could also result from the fact that NOS (a heme protein) consumes heme and out-competes the capacity of the heme-a maturation pathway (9), leaving the cells with a shortage for heme-a and complex IV, although the physiological advantages are unclear.

Proliferation or differentiation of cells depends on functional mitochondria and on a normal signal-transduction network. Because heme-deficient brain cells selectively lose complex IV (9) and have altered APP (Fig. 2), we investigated its consequences on cell division and neuronal differentiation. Heme-deficient SHSY5Y cells failed to differentiate and their axons degenerate, whereas heme-deficient U373 failed to proliferate. The signaling pathways in heme-deficient cells may be corrupted as a result of compromised HRM-dependent factors, APP, and decayed mitochondria. This hypothesis may partially explain the failed completion of proliferation or differentiation and suggests that the role of intracellular heme may be more complex than simply for cytochrome activity. Heme deficiency could influence HRM-dependent factors, where the level of “free protoheme” could serve as a signaling molecule, produced by mitochondria and exported to the cytosol signaling for normal function of the mitochondria. The low levels of “free protoheme” induced by inhibition with NMP would compromise HRM-dependent factors, and may serve to communicate to the nuclei about dysfunctional mitochondria. Our search for HRM-containing proteins also revealed that BTEB1, a transcription factor activated by growth factors (56), possesses three potential HRMs.

The consequences of heme deficiency on NOS, APP, complex IV, and iron and zinc homeostasis suggests that adequate levels of heme are essential for proper function of these proteins, and mitochondria could play a major role by maintaining an optimal supply of heme. APP also seems to bind and modulate the activity of heme oxygenase in the endoplasmic reticulum (57), which may be one mechanism to regulate the intracellular level of heme. Heme, or a heme-related component, seems to play a role in the physiology of AD because it inhibits the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (58). In addition, HasAh, a heme protein (59), has been colocalized with senile plaques. Neuroglobin, a heme protein in mammals, protects neurons after ischemia/reperfusion injury (60), and seems to play a role in AD (M. A. Smith, personal communication). Future research should elucidate the contribution of protoheme in these observations.

Several physiologically relevant factors seem to influence heme synthesis and thus drive age-related decay of mitochondria. These are aging, deficiency for specific micronutrients, and exposure to exogenous toxic metals. In addition, degradation of heme by heme oxygenase, which increased with age and in the brains of AD patients (61), may be a factor contributing to changes in the metabolism of iron and heme with age. Deficiency in mitochondrial heme synthesis could initiate the metabolic changes of the brain during aging and neurodegeneration. The metabolism of heme and specifically heme-a remain unexplored topics especially in the aging brain and deserve greater attention.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Smith and William H. Frey II for comments on the paper and Carla Schultz and Jeff Helgager for technical help. This work was supported by Ellison Medical Foundation Senior Investigator Grant SS-0422-99, National Institute on Aging Grant R01-AG17140, National Foundation for Cancer Research Grant 00-CHORI, and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Center Grant P30-ES01896 (to B.N.A.).

Abbreviations

NO, nitric oxide

NOS, NO synthase

NOS1, neuronal NOS

APP, amyloid precursor protein

NMP, N-methylprotoporphyrin IX

AD, Alzheimer's disease

HRM, heme regulatory motif

References

- 1.Parker W. D., Parks, J., Filley, C. M. & Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B. K. (1994) Neurology 44, 1090-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albers D. S. & Beal, M. F. (2000) J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 59, 133-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beal M. F. (2000) Trends Neurosci. 23, 298-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valla J., Berndt, J. D. & Gonzalez-Lima, F. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 4923-4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith M. A., Nunomura, A., Zhu, X., Takeda, A. & Perry, G. (2000) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2, 413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartzokis G., Sultzer, D., Cummings, J., Holt, L. E., Hance, D. B., Henderson, V. W. & Mintz, J. (2000) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57, 47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bitar M. & Weiner, M. (1983) Mech. Ageing Dev. 23, 285-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atamna H., Walter, P. & Ames, B. N. (2002) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 397, 345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atamna H., Liu, J. & Ames, B. N. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48410-48416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L. & Guarente, L. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 313-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogawa K., Sun, J., Taketani, S., Nakajima, O., Nishitani, C., Sassa, S., Hayashi, N., Yamamoto, M., Shibahara, S., Fujita, H. & Igarashi, K. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 2835-2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y. C., Masutani, H., Yamaguchi, Y., Itoh, K., Yamamoto, M. & Yodoi, J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18399-18406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii D. N. & Maniatis, G. M. (1978) Nature 274, 372-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakimoto P. & Block, G. (2001) J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, 65-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muzyka V., Bogovski, S., Viitak, A. & Veidebaum, T. (2002) Sci. Total Environ. 286, 73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beri R. & Chandra, R. (1993) Drug Metab. Rev. 25, 49-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taketani S., Adachi, Y. & Nakahashi, Y. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 4685-4692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furukawa T., Kohno, H., Tokunaga, R. & Taketani, S. (1995) Biochem. J. 310, 533-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozoff B., Jimenez, E., Hagen, J., Mollen, E. & Wolf, A. W. (2000) Pediatrics 105, E51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter P. B., Knutson, M. D., Paler-Martinez, A., Lee, S., Xu, Y., Viteri, F. E. & Ames, B. N. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2264-2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benton D. (2001) Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 25, 297-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura T., Goldenberg, R. L., Hou, J., Johnston, K. E., Cliver, S. P., Ramey, S. L. & Nelson, K. G. (2002) J. Pediatr. 140, 165-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Deungria M., Rao, R., Wobken, J. D., Luciana, M., Nelson, C. A. & Georgieff, M. K. (2000) Pediatr. Res. 48, 169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedman M. L. (1987) Blood Cells 13, 227-235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sangerman J., Killilea, A., Chronister, R., Pappolla, M. & Goodman, S. R. (2001) Brain Res. Bull. 54, 405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole S. P. & Marks, G. S. (1984) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 64, 127-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamble J. T., Dailey, H. A. & Marks, G. S. (2000) Drug Metab. Dispos. 28, 373-375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tangeras A. (1986) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 882, 77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs J. M., Sinclair, P. R., Sinclair, J. F., Gorman, N., Walton, H. S., Wood, S. G. & Nichols, C. (1998) Toxicology 125, 95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbanac D., Milin, C., Domitrovic, R., Giacometti, J., Pantovic, R. & Ciganj, Z. (1997) Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 57, 91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LoPresti P., Poluha, W., Poluha, D. K., Drinkwater, E. & Ross, A. H. (1992) Cell Growth Differ. 3, 627-635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pledger W. J., Howe, P. H. & Leof, E. B. (1982) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 397, 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirai K., Aliev, G., Nunomura, A., Fujioka, H., Russell, R. L., Atwood, C. S., Johnson, A. B., Kress, Y., Vinters, H. V., Tabaton, M., et al. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 3017-3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattson M. P. & Chan, S. L. (2001) J. Mol. Neurosci. 17, 205-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell A., Smith, M. A., Sayre, L. M., Bondy, S. C. & Perry, G. (2001) Brain Res. Bull. 55, 125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selkoe D. J. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 741-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ando K., Iijima, K. I., Elliott, J. I., Kirino, Y. & Suzuki, T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40353-40361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu W. Q., Ferreira, A., Miller, C., Koo, E. H. & Selkoe, D. J. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 2157-2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zambrano N., Bruni, P., Minopoli, G., Mosca, R., Molino, D., Russo, C., Schettini, G., Sudol, M. & Russo, T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19787-19792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y., McPhie, D. L., Hirschberg, J. & Neve, R. L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8929-8935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheuermann S., Hambsch, B., Hesse, L., Stumm, J., Schmidt, C., Beher, D., Bayer, T. A., Beyreuther, K. & Multhaup, G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33923-33929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh D. M., Tseng, B. P., Rydel, R. E., Podlisny, M. B. & Selkoe, D. J. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 10831-10839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Multhaup G., Scheuermann, S., Schlicksupp, A., Simons, A., Strauss, M., Kemmling, A., Oehler, C., Cappai, R., Pipkorn, R. & Bayer, T. A. (2002) Free Radical Biol. Med. 33, 45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lynch T., Cherny, R. A. & Bush, A. I. (2000) Exp. Gerontol. 35, 445-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Powell S. R. (2000) J. Nutr. 130, 1447S-1454S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan S. D., Yan, S. F., Chen, X., Fu, J., Chen, M., Kuppusamy, P., Smith, M. A., Perry, G., Godman, G. C., Nawroth, P., et al. (1995) Nat. Med. 1, 693-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Good P. F., Perl, D. P., Bierer, L. M. & Schmeidler, J. (1992) Ann. Neurol. 31, 286-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lovell M. A., Robertson, J. D., Teesdale, W. J., Campbell, J. L. & Markesbery, W. R. (1998) J. Neurol. Sci. 158, 47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panayi A. E., Spyrou, N. M., Iversen, B. S., White, M. A. & Part, P. (2002) J. Neurol. Sci. 195, 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Potocnik F. C., van Rensburg, S. J., Park, C., Taljaard, J. J. & Emsley, R. A. (1997) S. Afr. Med. J. 87, 1116-1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schueck N. D., Woontner, M. & Koeller, D. M. (2001) Mitochondrion 1, 51-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouton C. (1999) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55, 1043-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goessling L. S., Mascotti, D. P. & Thach, R. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12555-12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iacopetta B. & Morgan, E. (1984) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 805, 211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith M. A., Richey Harris, P. L., Sayre, L. M., Beckman, J. S. & Perry, G. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 2653-2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X. L., Simmen, F. A., Michel, F. J. & Simmen, R. C. (2001) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 181, 81-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takahashi M., Dore, S., Ferris, C. D., Tomita, T., Sawa, A., Wolosker, H., Borchelt, D. R., Iwatsubo, T., Kim, S. H., Thinakaran, G., et al. (2000) Neuron 28, 461-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fawcett J. R., Bordayo, E. Z., Jackson, K., Liu, H., Peterson, J., Svitak, A. & Frey, W. H., II (2002) Brain Res. 950, 10-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castellani R. J., Harris, P. L., Lecroisey, A., Izadi-Pruneyre, N., Wandersman, C., Perry, G. & Smith, M. A. (2000) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2, 137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun Y., Jin, K., Mao, X. O., Zhu, Y. & Greenberg, D. A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 15306-15311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith M. A., Kutty, R. K., Richey, P. L., Yan, S. D., Stern, D., Chader, G. J., Wiggert, B., Petersen, R. B. & Perry, G. (1994) Am. J. Pathol. 145, 42-47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]