Abstract

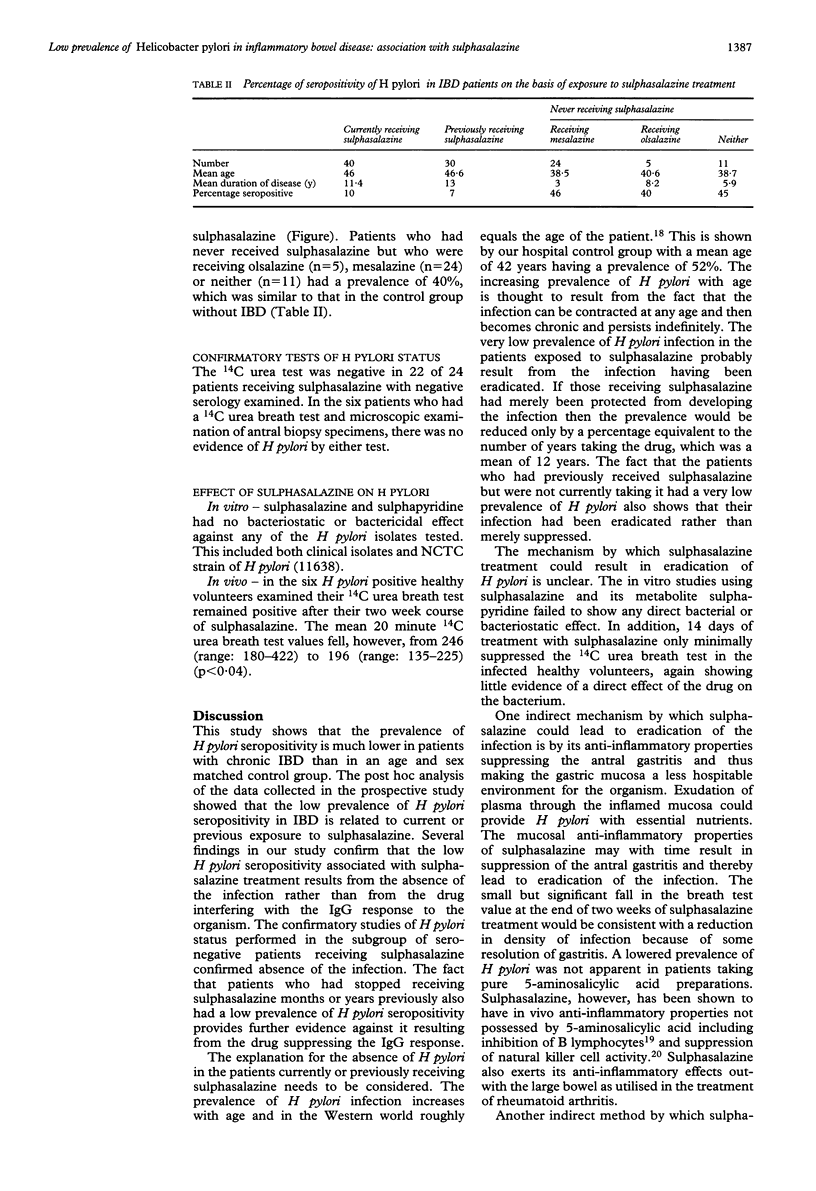

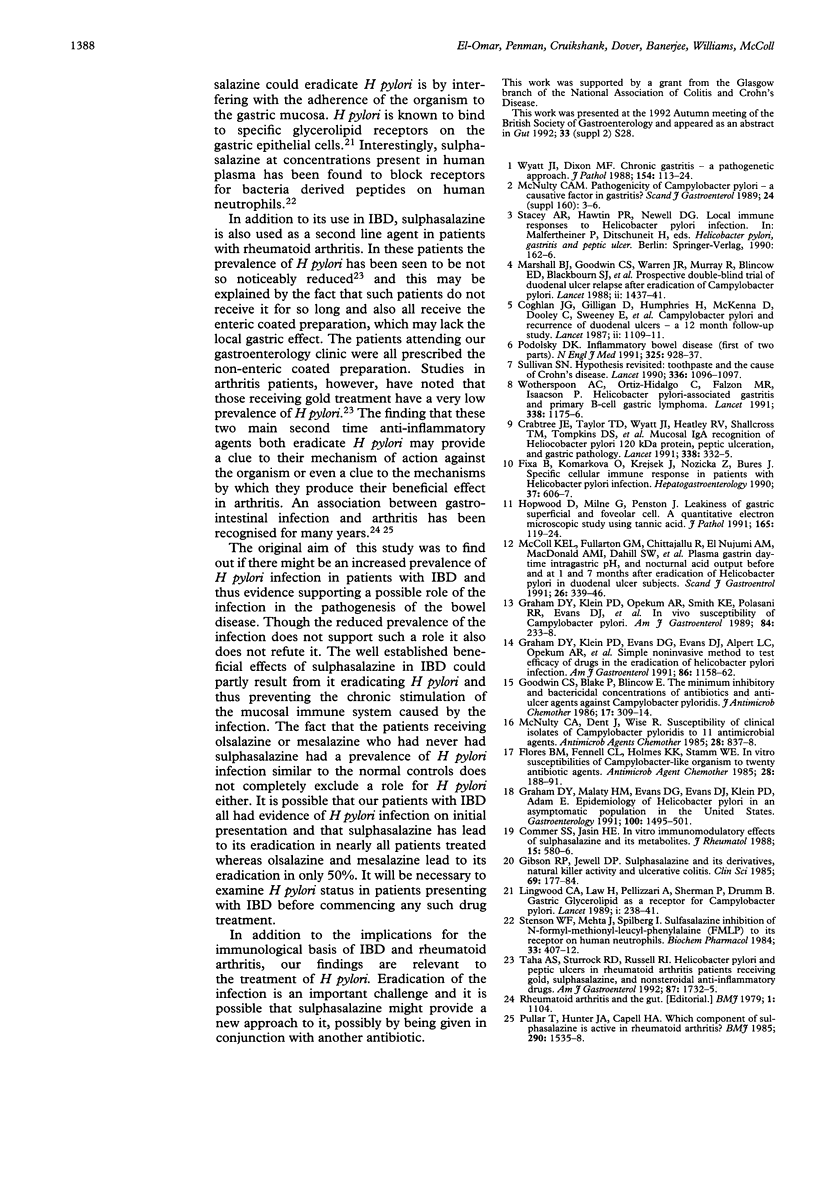

The prevalence of IgG antibodies to Helicobacter pylori was examined in 110 patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (63 ulcerative colitis, 47 Crohn's disease) and compared with 100 age and sex matched control patients. The overall prevalence of H pylori seropositivity in the IBD patients was 22%, which was significantly less than that of 52% in the controls (p < 0.002). There was no difference in prevalence between ulcerative colitis and Crohn's patients. The low seropositivity in the IBD patients resulted from a very low prevalence of 10% in those currently receiving sulphasalazine (n = 40) and similarly low prevalence of 7% in those previously receiving sulphasalazine (n = 30). In those receiving olsalazine or mesalazine and who had never had sulphasalazine, the prevalence of seropositivity was 45%. Further studies using 14C urea breath test and microscopy of antral biopsy specimens confirmed that the negative serology in patients receiving sulphasalazine resulted from absence of the infection rather than absence of humoral immune response to it. In six control patients with H pylori infection, a two week course of sulphasalazine (500 mg four times daily) only caused slight suppression of the 14C urea breath test. In vitro studies failed to show any direct antibacterial effect of sulphasalazine on H pylori. These findings indicate that longterm treatment with sulphasalazine leads to eradication of H pylori infection and that this does not result from a direct antibacterial effect. It may be caused by the drug treating the gastritis and thereby depriving the bacterium of essential nutrients exuded by the inflamed mucosa.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Coghlan J. G., Gilligan D., Humphries H., McKenna D., Dooley C., Sweeney E., Keane C., O'Morain C. Campylobacter pylori and recurrence of duodenal ulcers--a 12-month follow-up study. Lancet. 1987 Nov 14;2(8568):1109–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer S. S., Jasin H. E. In vitro immunomodulatory effects of sulfasalazine and its metabolites. J Rheumatol. 1988 Apr;15(4):580–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree J. E., Taylor J. D., Wyatt J. I., Heatley R. V., Shallcross T. M., Tompkins D. S., Rathbone B. J. Mucosal IgA recognition of Helicobacter pylori 120 kDa protein, peptic ulceration, and gastric pathology. Lancet. 1991 Aug 10;338(8763):332–335. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90477-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixa B., Komárková O., Krejsek J., Nozicka Z., Bures J. Specific cellular immune response in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990 Dec;37(6):606–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores B. M., Fennell C. L., Holmes K. K., Stamm W. E. In vitro susceptibilities of Campylobacter-like organisms to twenty antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Aug;28(2):188–191. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson P. R., Jewell D. P. Sulphasalazine and derivatives, natural killer activity and ulcerative colitis. Clin Sci (Lond) 1985 Aug;69(2):177–184. doi: 10.1042/cs0690177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. S., Blake P., Blincow E. The minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentrations of antibiotics and anti-ulcer agents against Campylobacter pyloridis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1986 Mar;17(3):309–314. doi: 10.1093/jac/17.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D. Y., Klein P. D., Evans D. G., Evans D. J., Jr, Alpert L. C., Opekun A., Jerdack G. R., Morgan D. R. Simple noninvasive method to test efficacy of drugs in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: the example of combined bismuth subsalicylate and nitrofurantoin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991 Sep;86(9):1158–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D. Y., Klein P. D., Opekun A. R., Smith K. E., Polasani R. R., Evans D. J., Jr, Evans D. G., Alpert L. C., Michaletz P. A., Yoshimura H. H. In vivo susceptibility of Campylobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989 Mar;84(3):233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D. Y., Malaty H. M., Evans D. G., Evans D. J., Jr, Klein P. D., Adam E. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in an asymptomatic population in the United States. Effect of age, race, and socioeconomic status. Gastroenterology. 1991 Jun;100(6):1495–1501. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90644-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood D., Milne G., Penston J. Leakiness of gastric superficial and foveolar cells. A quantitative electron microscopic study using tannic acid. J Pathol. 1991 Oct;165(2):119–124. doi: 10.1002/path.1711650206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingwood C. A., Law H., Pellizzari A., Sherman P., Drumm B. Gastric glycerolipid as a receptor for Campylobacter pylori. Lancet. 1989 Jul 29;2(8657):238–241. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall B. J., Goodwin C. S., Warren J. R., Murray R., Blincow E. D., Blackbourn S. J., Phillips M., Waters T. E., Sanderson C. R. Prospective double-blind trial of duodenal ulcer relapse after eradication of Campylobacter pylori. Lancet. 1988 Dec 24;2(8626-8627):1437–1442. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90929-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl K. E., Fullarton G. M., Chittajalu R., el Nujumi A. M., MacDonald A. M., Dahill S. W., Hilditch T. E. Plasma gastrin, daytime intragastric pH, and nocturnal acid output before and at 1 and 7 months after eradication of Helicobacter pylori in duodenal ulcer subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991 Mar;26(3):339–346. doi: 10.3109/00365529109025052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty C. A., Dent J., Wise R. Susceptibility of clinical isolates of Campylobacter pyloridis to 11 antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Dec;28(6):837–838. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.6.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky D. K. Inflammatory bowel disease (1) N Engl J Med. 1991 Sep 26;325(13):928–937. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109263251306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullar T., Hunter J. A., Capell H. A. Which component of sulphasalazine is active in rheumatoid arthritis? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985 May 25;290(6481):1535–1538. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6481.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenson W. F., Mehta J., Spilberg I. Sulfasalazine inhibition of binding of N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (FMLP) to its receptor on human neutrophils. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984 Feb 1;33(3):407–412. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S. N. Hypothesis revisited: toothpaste and the cause of Crohn's disease. Lancet. 1990 Nov 3;336(8723):1096–1097. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92572-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha A. S., Sturrock R. D., Russell R. I. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcers in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving gold, sulfasalazine, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992 Dec;87(12):1732–1735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotherspoon A. C., Ortiz-Hidalgo C., Falzon M. R., Isaacson P. G. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991 Nov 9;338(8776):1175–1176. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt J. I., Dixon M. F. Chronic gastritis--a pathogenetic approach. J Pathol. 1988 Feb;154(2):113–124. doi: 10.1002/path.1711540203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]