Abstract

A combination of quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping and microarray analysis was developed and used to identify 34 candidate genes for ovariole number, a quantitative trait, in Drosophila melanogaster. Ovariole number is related to evolutionary fitness, which has been extensively studied, but for which few a priori candidate genes exist. A set of recombinant inbred lines were assayed for ovariole number, and QTL analyses for this trait identified 5,286 positional candidate loci. Forty deletions spanning the QTL were employed to further refine the map position of genes contributing to variation in this trait between parental lines, with six deficiencies showing significant effects and reducing the number of positional candidates to 548. Parental lines were then assayed for expression differences by using Affymetrix microarray technology, and ANOVA was used to identify differentially expressed genes in these deletions. Thirty-four genes were identified that showed evidence for differential expression between the parental lines, one of which was significant even after a conservative Bonferroni correction. The list of potential candidates includes 5 genes for which previous annotations did not exist, and therefore would have been unlikely choices for follow-up from mapping studies alone. The use of microarray technology in this context allows an efficient, objective, quantitative evaluation of genes in the QTL and has the potential to reduce the overall effort needed in identifying genes causally associated with quantitative traits of interest.

Keywords: quantitative trait locus, genomics, ovariole, deficiency mapping

The candidate gene approach has proven extremely powerful for studying the genetic architecture of complex traits. However, for some traits of interest, a priori candidate genes based on a biological model either do not exist or are so numerous that individual follow-up is prohibitively expensive (1). Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping is frequently used to identify genomic regions associated with a phenotypic trait of interest. Such regions are generally large, containing thousands of putative genes. By definition, all genes in the QTL are candidate loci for the trait. Fine mapping within the QTL can reduce the number of candidate genes to the hundreds. Even after fine mapping, however, one may be left with more candidates than can feasibly be pursued, as validation procedures are expensive and time-consuming, and can be applied to only a handful of candidate loci. In the absence of a priori candidates, selection of loci for validation must be based in part on a combination of QTL mapping and fine mapping experiments, and in part on biological intuition. There is a need for yet another experimental step in the march from QTL to gene, to bridge the gap between fine mapping, which yields hundreds of genes, and validation studies, which can be applied to at most tens of genes. Experimental techniques to systematically reduce the list of putative loci, while controlling type I and type II error, would be a welcome addition to the process of candidate gene identification. Quantitative expression studies are one method that could be used to bring the number of genes to be validated to a reasonable size.

Recent work suggests that regulatory variation is important in a variety of complex traits, in many organisms (1–3). Quantitative expression studies, such as microarray technology, can reveal regulatory variation in genes for complex traits, including traits for which a priori candidates do not exist. Array analysis alone would reveal interesting variation between lines of organisms, but would not link the variation to a particular phenotype. By combining QTL mapping and fine mapping with arraying, we can identify positional candidate genes for a phenotype of interest whose expression varies between parental lines. The goal of this integrated approach is neither to create an exhaustive list of candidates, as this technique will almost certainly result in type II error, nor to definitively establish a causal link between a gene and a phenotype. Rather, the goal is to identify a manageable number of genes for follow-up by using an approach that enables the investigator to successfully identify candidate loci associated with the phenotype of interest, with defined probabilities of type I and type II error.

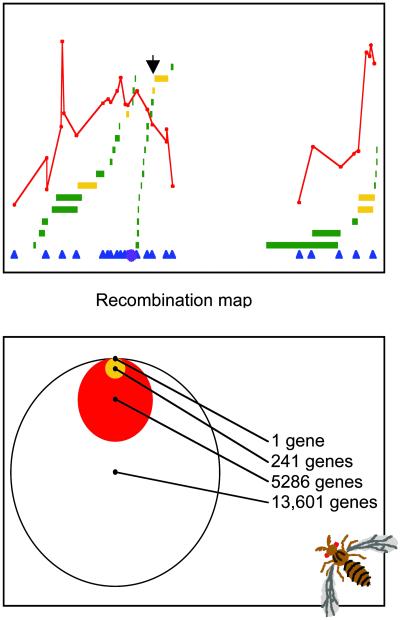

Ovariole number is a trait in Drosophila melanogaster of evolutionary significance, as it is related to female fecundity (4, 5), and it varies clinally with latitude (6). However, little is known about the developmental genetics of ovarigenesis, so few a priori candidate genes for the trait exist. Two large genomic regions associated with ovariole number were identified by using QTL analysis on a recombinant inbred mapping population derived from two laboratory lines of D. melanogaster, Oregon-R and 2b (7). However, these QTL encompass 5,286 genes as positional candidate loci (Table 1, Fig. 1). Fine mapping of the QTL was performed by using the deficiency mapping technique (8), including 40 deficiencies covering 74% of the QTL (3,894 genes as estimated by the Drosophila Genome Project). Six deficiencies containing a total of 548 genes varied significantly between parental lines; 2,018 were eliminated (M.L.W., L. Jacobs, A. Kuntz, and L.-Y. Shen, unpublished work). The combination of QTL mapping and deficiency mapping reduced the size of the regions, effectively reducing the number of putatively involved genes from the whole genome (13,601 genes) to only 548 genes.

Table 1.

Numbers and classifications of genes

| Category | Estimated number of genes from genome project | Genes present on array |

|---|---|---|

| Genes in QTL | 5,286 | 3,841 |

| Total genes in deficiencies | 3,894 | 2,566 |

| Genes in significant deficiencies | 548 | 306 |

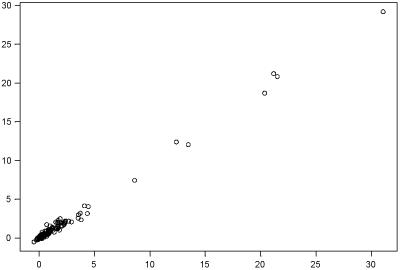

Fig 1.

For each of the 294 genes under consideration, the mean expression of the Oregon-R replicates is plotted on the x axis and the mean of the 2b replicates is plotted on the y axis. Means were calculated after normalization.

To identify a list of candidate loci that can be effectively validated, we decided to focus on variation caused by regulatory mutations, rather than structural mutations, both because of efficiency of detection and because of renewed interest in the role of regulatory variation in evolution. One means of assaying variation in regulatory mutations is by looking for differences in gene expression. Several techniques exist for assaying variation in gene expression of many loci simultaneously. We used Affymetrix whole Drosophila genome microarray chips to screen for variation in gene expression. We hypothesized that by examining the regions identified by the sequential QTL/deficiency mapping for variation in gene expression, we could identify a manageable list of candidate loci.

Methods

Fine mapping of QTL was conducted by using the technique of overlapping deficiencies (deletions) developed by Pasyukova et al. (8). In brief, the two parental lines' performances when heterozygous with the deficiency are compared with their performances when heterozygous with a nonrecombining balancer chromosome. The analysis consisted of a two-way factorial ANOVA with main effects line (Oregon-R or 2b) and genotype (deficiency or balancer): Yijk = μ + λi + γj + (λγ)ij + ɛijk where Yijk is the ovariole number for individual k from line i and genotype j. We are interested only in those cases where the deficiency is allelic to a gene for ovariole number that differs between the parental lines, i.e., in that subset of deficiencies (λγ)ij ≠ 0 where the significant difference is between the means of the deficiency genotypes, rather than the balancer genotypes. Forty deficiencies were evaluated covering ≈74% of the genes in the QTL (M.L.W., L. Jacobs, A. Kuntz, and L.-Y. Shen, unpublished work). Of these deficiencies, six showed a significant line × genotype interaction in the correct direction, indicating the presence of at least one gene of interest in the deficiency.

Often, the breakpoints of deficiencies are given as a range, rather than a precise cytological position, or as a lettered band position without specifying a numbered subdivision. In these cases, the “broadest” deficiency was chosen. For example, for a deficiency such as BL2612, the breakpoints are listed as 68C8–11 and 69B4–5; we included genes with cytological positions between 68C8 and 69B5. For a deficiency such as BL2992, the breakpoints are listed as 71C and 71F. We included genes with cytological positions anywhere within or between these lettered bands.

Flies for mRNA extraction were maintained at conditions identical to those of the phenotypic assay (7). Extraction was performed on animals ranging from late-third-instar larvae to 48-h pupae, the informative stage for ovariole number (10), which coincides with the ecdysone pulses at the larval/prepupal transition and the prepupal/pupal transition. Individuals from each genotype were pooled from 25 independent vials to eliminate between-vial variation. Each pooled sample was split into three replicates, and RNA extractions, RT-PCRs, and labeling reactions were performed independently for each replicate. The six samples were then hybridized to Affymetrix Drosophila genome chips.

The 14,010 features on the Affymetrix Drosophila genome chip were grouped into four categories based on the results of the QTL/deficiency mapping experiments: not in the QTL (10,148); in the QTL but not covered in a deficiency (1,285); in at least one deficiency that was not significant (2,283); or in a significant deficiency (294). There were 254 genes in significant deficiencies listed in the Drosophila genome that were not on the Affymetrix Drosophila genome chip at the time of this experiment.

For each feature, which represents the combined expression data from all relevant probe pairs on the chip, the ANOVA model Yij = μ + λi + ɛij was fit, where Yij is the observed expression for line (λ) i, replicate j, and μ is the overall mean expression for the feature. λ is an indicator variable for the parental line [i = 1 (Oregon-R) or 0 (2b)] (11, 12). Negative values were considered missing data (12), and features with two or more missing values within a genotype were considered uninformative. For informative features, the P value for the test of the null hypothesis λ1 = λ0 (i.e., mean expression not different between Oregon-R and 2b) was calculated by using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC; 1988).

Results

Variation in mRNA abundance was evaluated by microarray assay for the two parental lines (Fig. 2). Extraction of mRNA was performed on animals at the informative stage for ovariole number development (10). Three replicates of each genotype were hybridized to Affymetrix Drosophila genome chips. The complete results of the ANOVA are reported in Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. The raw data (Affymetrix CEL files), from which all results were generated, are also published in the supporting information on the PNAS web site. For the 294 features in the significant deficiencies that were present on the array, 56 were uninformative, leaving 238 informative features.

Fig 2.

(Upper) The black arrow highlights the recombinational map position of the candidate genes CG17327, yellow-f, and Su(fu). Red curves indicate the value of the test statistic for the presence of QTL (7). Blue triangles indicate cytological markers used in the QTL experiment; the purple star represents the centromere. Horizontal bars are the deficiencies that were tested; gold bars showed a significant interaction across parents and genotypes, whereas green bars did not (M.L.W., L. Jacobs, A. Kuntz, and L.-Y. Shen, unpublished work). Deficiencies are staggered in height for presentation purposes. (Lower) Venn diagram showing systematic narrowing of list of candidate genes from all genes in the genome (open circle), to genes mapped in the QTL (red circle), to genes identified by deficiency mapping present on the array (gold circle), to genes differentially expressed between the parental lines by Bonferroni criteria (CG17327, black dot).

In both QTL mapping and deficiency mapping techniques, the type I and type II error rate is well understood. General statistical theory indicates that type I and type II error are inversely related, with the decrease in false positives (type I) being associated with the increase in false negatives (type II), and vice versa (13). By using an ANOVA approach to the analysis of the expression data, where the interplay between type I and type II error has been well studied, we were able to examine two different strategies for creating a list of genes for future validation.

One strategy is to attempt to reduce the occurrence of type I error as much as possible, at the expense of increasing type II error. Using the Bonferroni correction ensures that the type I error (false positives) for the entire experiment is less than or equal to the nominal α chosen. Of the 238 informative features, one feature, 149813_at, was determined to have significantly different expression between the parental lines when the ANOVA approach (11, 12) was used with a Bonferroni corrected significance level of 2.1 × 10−4 (0.05/248) (Fig. 2). However, the Bonferroni correction is overly conservative when hypothesis tests are correlated (14–16), and thus the actual α is likely to be substantially less than the nominal α in this case.

Alternatively, an arbitrary a priori significance level of 0.01 for each test can be used. A significance level of 0.01 will increase the type I error rate to the point of almost certainly identifying some false positives. However, it will also reduce the number of false negatives. For our data, there are 21 features identified in the significant deficiencies when an arbitrary significance level of 0.01 is used. These features occur in the deficiencies BL3007, BL2612, BL2352, BL3009 Sam, and BL669. Interestingly, two of the features identified (149844_f_at and 151038_at) occur independently in two deficiencies, both of which were identified by the deficiency mapping technique. These additional 21 features are summarized in Table 2 and are hereafter referred to as the second-tier list.

Table 2.

List of positional candidate genes based on sequential QTL/deficiency mapping and microarray

| Category | Feature | P value | Annotation | Cytological position | Bloomington deficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonferroni P < 0.01 | 149813_at | 0.0000268 | CG17327 | 87D9 | BL3007 |

| 152300_at | 0.003189 | CG18593 | 68E4 | BL2612 | |

| 148633_at | 0.003232 | CG10861 | 68F5 | BL2612 | |

| 142283_at | 0.008525 | Neurexin | 68F5 | BL2612 | |

| 153324_at | 0.00236 | Su(fused) | 87C8 | BL3007 | |

| 149796_at | 0.004569 | CG14394 | 87C8 | BL3007 | |

| 152571_at | 0.001876 | CG7966 | 87D11 | BL3007 | |

| 149815_at | 0.005197 | CG11668 | 87D11 | BL3007 | |

| 152200_at | 0.008558 | rosy | 87D11 | BL3007 | |

| 142349_at | 0.001085 | yellow-f | 87D9 | BL3007 | |

| 154631_at | 0.003146 | CG7472 | 87D9 | BL3007 | |

| 149812_at | 0.009465 | CG7488 | 87D9 | BL3007 | |

| 149844_f_at | 0.008709 | Actin 87E | 87E11 | BL3007, BL3009S | |

| 151038_at | 0.007555 | CG11686 | 87E4 | BL3007, BL3009S | |

| 153409_at | 0.005996 | B52 | 87F7 | BL3009S | |

| 151110_at | 0.000884 | CG11500 | 99B3 | BL669 | |

| 153339_at | 0.007618 | CG7920 | 99D4 | BL2352 | |

| 153625_at | 0.005115 | Sry-beta | 99D5 | BL2352 | |

| 154838_at | 0.006865 | Axn | 99D5 | BL2352 | |

| 150871_at | 0.005577 | CG15526 | 99D6 | BL2352 | |

| 153139_at | 0.007402 | CG7950 | 99D6 | BL2352 | |

| Flanking regions added, P < 0.01 | 143646_at | 0.004389 | Pbprp1 | 69B2 | BL2612, Df(3L)iro2 |

| 148655_at | 0.004427 | CG14124 | 69B2 | BL2612, Df(3L)iro2 | |

| 142239_at | 0.001602 | CG10424 | 75F6 | NA | |

| 151832_at | 0.00104 | CG8782 | 76C1 | NA | |

| 149755_at | 0.009581 | CG10091 | 87B12 | BL3007, BL3003 | |

| 149769_at | 0.005017 | CG17227 | 87B14 | BL3007, BL3003 | |

| 149748_at | 0.001902 | CG18158 | 87B9 | BL3007, BL3003 | |

| 149782_at | 0.0000585 | CG6489 | 87C1 | BL3007, BL3003 | |

| 151036_f_at | 0.006876 | CG5834 | 87C1 | BL3007, BL3003 | |

| 153150_at | 0.000632 | CG11899 | 99A5 | BL4305, BL669 | |

| 150841_at | 0.008503 | CG1973 | 99C2 | NA | |

| 152879_at | 0.00288 | CG7802 | 99C5 | NA | |

| 152769_at | 0.000198 | CG7814 | 99C7 | NA |

Category refers to which statistical procedure was used. Feature is the Affymetrix name for the feature on the chip. P values were determined by ANOVA as described in Methods. Bloomington deficiency refers to the deficiencies that contain the feature, or NA if the feature lies outside any deficiencies screened.

Another potential source of error is the precision in determining the deficiency breakpoints, as some investigators are better cytologists than others. Again considering our second approach, that of reducing type II error at the cost of increasing type I error, we might wish to consider the flanking regions of the six significant deficiencies. Flanking regions were defined as one lettered subdivision away from the reported breakpoints. If we consider features with a significance level of 0.01 in the flanking regions, we identify 13 additional features for a total of 34 features (Table 2), which are hereafter referred to as the third-tier list. Conversely, the deficiencies can be reduced in size by one lettered subdivision, leaving nine features (142283_at, 148633_at, 142349_at, 149812_at, 149813_at, 149815_at, 152200_at, 152571_at, and 154631_at; Table 2).

Discussion

By combining array technology with mapping techniques, we were able to identify candidate genes for intensive follow-up studies for ovariole number in D. melanogaster. While ovariole number is a quantitative trait of evolutionary interest, its developmental genetics is poorly understood, such that there are few a priori candidate genes for the trait. For the locus identified by using Bonferroni criteria, CG17327, there is effectively no annotation. Thus, if a traditional candidate gene approach in the absence of gene expression data had been used, this locus would not have been tagged for further consideration. Querying with psi blast (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) revealed that the protein sequence of CG17327 displays significant homology to two genes: E2IG2 protein from Homo sapiens (accession no. NM_016565; 40% amino acid identity and E value 1.0 × 10−4), and a hypothetical protein from Schizosaccharomyces pombe (accession no. T41376; 40% identity and E value 3.0 × 10−4). The developmental stage of the flies that is relevant to ovariole number determination coincides with the ecdysone pulses at the larval/prepupal transition and the prepupal/pupal transition (17), suggesting that proteins involved in ovariole number might be part of the ecdysone regulatory cascade. Interestingly, the human protein was identified in a screen for novel targets of the steroid hormone estrogen. Ecdysone, an insect hormone, is chemically similar to mammalian steroid hormones. The homology between the Drosophila and Homo proteins may suggest a similar regulatory mechanism.

Second- and third-tier lists of candidates (21 and 13 genes, respectively) were also constructed, using a type I error rate of 0.01 per test. Two members of the second-tier list stand out as particularly good candidates: 142349_at (yellow-f, P < 0.001) and 153324_at [Suppressor of fused, Su(fu), P < 0.002]. yellow-f is a member of the yellow gene family in D. melanogaster (18, 19) and has significant homology to the royal jelly family of proteins (18). Royal jelly is fed to hymenopteran larva(e) destined to become the queen(s), and is thought to be responsible for the attainment of full reproductive potential, which frequently includes an increase in ovariole number (20, 21). Su(fu) affects ovary formation, is a member of the hedgehog signaling pathway, and interacts genetically with fused, a gene that affects ovariole number (9).

To confirm the role of any of the genes described above in ovariole number determination, validation studies such as TaqMan, RNA interference (RNAi), transformation, and/or correlation between mRNA expression in natural populations and variation in ovariole number are essential. Because of the labor and expense of such studies, only a small number of candidate genes may be studied so intensively. By adding a quantitative evaluation step after completing a fine mapping study, an investigator can more objectively determine type I and type II error rates entering into the validation process. Type I and type II error may also be influenced by data quantification software (i.e., dChip, Probe Profiler) and other transformations of the raw data [Cui, X., Kerr, M. K. & Churchill, G. A. (2002) “Data transformations for cDNA microarray data” at www.jax.org/research/churchill/]. Thus, in addition to the inclusion threshold chosen, issues surrounding data quantification and transformation are important for investigators to actively address, particularly given the lack of consensus as to the best analytical tools and the rapid evolution of array software and statistics. Taking these and more traditional experimental design questions into consideration, nominal type I or type II error rates for gene expression data can be adjusted to allow for the individual investigator's time and resources available for validation studies.

The construction of a manageable list of candidates is essential for direct assessment of causation between the candidate genes and the phenotype of interest. The combination of QTL/deficiency mapping and quantitative microarray analysis yields candidate genes where none existed before, a necessary first step for functional analysis of the genotype–phenotype relationship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research's Microarray Core Facility for excellent technical assistance, particularly Mick Popp, Tammy Flagg, and Sharon Norton. We also thank Laura Higgins, Michael Miyamoto, and the anonymous reviewers for excellent comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM59884-02 (to M.L.W.) and U.S. Department of Agriculture Grant Initiative for Future Agriculture and Food Systems N0014-94-1-0318 (to L.M.M.).

Abbreviations

QTL, quantitative trait locus or loci

References

- 1.Mackay T. F. C. (2001) Annu. Rev. Genet. 35, 303-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stam L. F. & Laurie, C. C. (1996) Genetics 144, 1559-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doebley J. (1992) Trends Genet. 8, 302-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohet Y. & David, J. (1978) Oecologia 36, 295-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulétreau-Merle J., Allemand, R., Cohet, Y. & David, J. R. (1982) Oecologia 53, 323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wayne M. L., Hackett, J. B. & Mackay, T. F. C. (1997) Evolution 51, 1156-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wayne M. L., Hackett, J. B., Dilda, C. L., Nuzhdin, S. V., Pasyukova, E. G. & Mackay, T. F. C. (2001) Genet. Res. 77, 107-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasyukova E. G., Vieira, C. & Mackay, T. F. C. (2000) Genetics 156, 1129-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y. & Kalderon, D. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127, 2165-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahowald A. P. & Kambysellis, M. P. (1980) in Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, eds. Ashburner, M. & Wright, T. R. F. (Academic, London), pp. 141–224.

- 11.Kerr M. K. & Churchill, G. A. (2001) Genet. Res. 77, 123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfinger R. D., Gibson, G., Wolfinger, E. D., Bennett, L., Hamadeh, H., Bushel, P., Afshari, C. & Paules, R. S. (2001) J. Comput. Biol. 8, 625-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casella G. & Berger, R. L., (1990) Statistical Inference (Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove, CA).

- 14.Westfall P. H., Zaykin, D. V. & Young, S. S. (2002) Methods Mol. Biol. 184, 143-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntyre L. M., Martin, E. R., Simonsen, K. L. & Kaplan, N. L. (2000) Genet. Epidemiol. 19, 18-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doerge R. W. & Churchill, G. A. (1996) Genetics 142, 285-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fristrom D. K. & Fristrom, J. W. (1993) in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, eds. Bate, M. & Martinez Arias, A. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), Vol. 2, pp. 843–897. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maleszka R. & Kucharski, R. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270, 773-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drapeau M. D. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281, 611-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Donnell S. (1998) Annu. Rev. Entomol. 43, 323-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin H. R. & Winston, M. L. (1998) Can. Entomol. 130, 883-891. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.