Abstract

A rapid throughput screening system involving gene expression analysis was developed in order to investigate the potential of bioactive chemicals contained in natural health products as effective drug therapy, in particular the ability of these chemicals to alleviate the inflammatory response in human airway epithelial cells. A number of databases were searched to retrieve the information needed to properly analyze the gene expression profiles obtained. The gene expression of human bronchial epithelial cells infected with rhinovirus and/or exposed to platelet activating factor was analyzed. Following analysis of the gene expression data the total number of expressed proteins that may potentially act as a marker for monitoring the modulation of airway inflammation was narrowed to 19. Further studies will involve selecting antibodies for these proteins, culturing airway epithelial cells in the presence of extracts of natural health products, extracting the proteins and identifying them by western blot analysis.

Keywords: gene expression analysis, proteomic databases, airway epithelial cells

Introduction

Airway inflammation is a feature of lung diseases and is characterized by airway swelling, excessive airway secretions, cellular infiltration and increased airway responsiveness (1). These diseases include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis. Herbal medicinal products are composed of bioactive chemicals, some of which may have therapeutic usefulness and some which may be toxic (2). For example, echinacea preparations contain many potentially active ingredients, such as polysaccharides, glycoproteins, alkamides and flavonoids (3). This herbal medicine has been traditionally used for the treatment and prevention of upper respiratory tract infections and is usually marketed as an immune system booster (4). However, as with many other natural health products, much confusion exists concerning the therapeutic potential and pharmacological properties of echinacea.

As a result of the increased popularity of natural health products, herbal medicinal products, such as echinacea, are being used more and more to treat the symptoms of airway inflammatory diseases. However, the effects of these products on the inflammatory pathway have yet to be elucidated and the efficacy of these products in treating airway inflammation is still debatable. The development of microarray technology and gene expression analysis has proved to be a valuable tool in drug discovery and in understanding the molecular basis of human disease. By comparing the gene expression patterns of healthy airway tissue with airway tissue undergoing inflammation, it is possible to elucidate the genetic basis of airway inflammation and establish a means by which herbal medicinal products can be evaluated as to their effects on the inflammatory pathway.

The purpose of this study was to develop a rapid throughput screening system to investigate the potential of the bioactive chemicals contained in natural health products as effective drug therapy. Of particular interest is the ability of these bioactive chemicals to alleviate the inflammatory response in airway epithelial cells.

Methods

Cell Culture

The 16HBE14o- cell line, immortalized from primary cultures of nasal polyp epithelial cells using the SV40 gene (5), was a gift from Dr D. C. Gruenert (University of California, San Francisco). CFNPE9o− cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL) at pH 7.4 under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 (balance air) at 37°C. Cells were passaged every 4–5 days (at confluence) by exposure to 0.1% trypsin in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min, after which the cells were dislodged from the culture dish by gentle agitation and collected by centrifugation at 800 g for 5 min. PBS consisted of (mM): NaCl (137), KCl (2.7), Na2HPO4 (15.2) and KH2PO4 (1.5), pH 7.4. Pelleted cells were then resuspended in MEM at 5 × 106 cells ml−1, and plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells cm−2 in 60 mm plastic culture dishes (Falcon, Becton Dickson and Co., Lincoln Park, NJ).

Drug Treatment

Platelet Activating Factor (PAF) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., dissolved in ethanol and diluted to the desired concentration with MEM (final ethanol concentration was <0.01%). Cells were grown to confluence (usually 3–4 days) and treated with 10 µM PAF for 12 h. Non-PAF treated cells contained 0.01% ethanol to control for any potential ethanol effect. Cells infected with rhinovirus were incubated for 24 h in medium containing rhinovirus 14 (obtained from ATCC, Manassas, VA) at a viral concentration of 100 plaque forming units (PFUs)/ml. All incubations were conducted at 37°C.

RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Mississauga, ON). Briefly, upon termination of the incubation period, cells were washed twice with PBS at 4°C, followed by exposure to 600 µl Buffer RLT at 4°C for 5 min. Lysate was collected using a rubber policeman and transferred under RNase-free conditions to a collection tube and homogenized for 30 seconds using a Polytron fitted with a small volume rotor-stator. The homogenate was mixed with an equal volume of 70% ethanol and thoroughly mixed by trituration. Of the mixture, 700 µl was applied to an RNeasy mini column and centrifuged at 9000 g for 15 s. The column was washed by adding 700 µl of Buffer RW1 and centrifuging as before. The mini column was transferred to a new collection tube and dried by application of 500 µl of Buffer RPE. The mini column was centrifuged as before and the drying procedure was repeated. Finally, the mini column was transferred to a fresh collection tube and the RNA was eluted twice with RNase-free water (50 µl) and centrifugation as above.

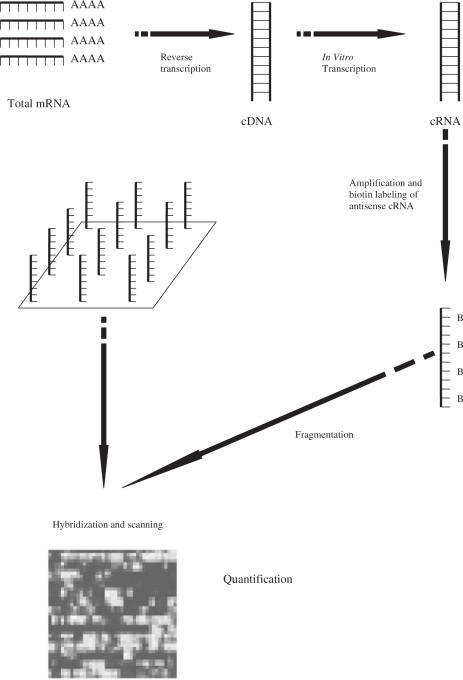

Gene Microarray

Microarray analysis was performed using the Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) HG-U133 A and B Human genome GeneChip® sets (containing probes for over 33 000 human genes) as described in the standard protocol outlined in the GeneChip® Expression Analysis Technical Manual (Affymetrix). Each experimental sample RNA was processed and run on separate HG-U133 chip sets. Briefly, cDNA was synthesized using T7-(dt)24 oligos and SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by T4 Polymerase and was purified using Phase Lock Gel (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) and phenol: chloroform extraction. Labeling was carried out using biotinylated CTP in an in vitro transcription reaction. The resulting labeled cRNA was then fragmented according to Affymetrix protocols and added to the recommended hybridization mixture. Approximately 10 µg of cRNA was used per Affymetrix U-133 GeneChip A and B® sets. Hybridization and washing were carried out in accordance with Affymetrix's established protocols. The probe array was scanned using an Affymetrix confocal laser scanner. The scanner generated an image of the array by exciting each feature with its laser, detecting the resulting photon emissions from the fluorescently labeled cRNA that had hybridized to the probes, and converting the detected photon emissions into a 16-bit intensity value (6,7). The amount of light emitted at 570 nm was proportional to the bound target at each location on the probe array (8). The probe array images generated by the scanner were then ready for analysis using the Affymetrix Microarray Suite software.

The use of microarray technology to monitor gene expression in cell lines and human tissues has become an important part of biological research. It allows for the analysis of biochemical pathways, the identification of the genes responsible for a particular phenotype and the assessment of the effect of a compound on the expression level of a large number of genes (6). The Affymetrix Microarray Suite software performed the operations necessary to process and analyze the probe array, including: image segmentation, background correction, scaling/normalizing arrays for array-to-array comparisons, calculation of statistics to indicate whether a gene transcript was present, and calculation of statistics to indicate whether a gene transcript was differentially expressed (6). The results of the analysis provided a list of genes that showed at least a 2-fold expression (upregulated and downregulated) compared with controls.

Online bioinformatic databases were used to analyze the results of the gene expression data. Proteomic databases were searched to determine the functions of the proteins coded by the expressed genes. Once these proteins were identified and studied, a set was chosen to be indicators for changes in airway inflammation. The purpose of these indicator proteins is to identify which bioactive compounds affect the inflammation process. Bioactive compounds with anti-inflammatory activities would be able to prevent the upregulated or downregulated expression of the indicator proteins which are otherwise expressed under conditions of airway inflammation, when the bioactive compound is not present. The ultimate objective was to determine which bioactive compounds of natural health products are effective in alleviating the airway inflammatory response and could prove useful in the treatment of airway diseases and conditions.

Results

Human bronchial epithelial cells were infected with rhinovirus and/or exposed to PAF, producing three experimental groups: PAF and no virus, virus and no PAF, and both virus and PAF. The control group was made up of cells with neither virus nor PAF. Three plates were grown for each of the three experimental groups and four plates were grown for the control group, giving a total of 13 samples analyzed with the Affymetrix GeneChip HG U133A microarray. The results from the four samples of controls showed an average of 43.7% of the probe sets evaluated as being present.

Following analysis of the gene expression data using proteomic databases, the genes of interest were narrowed down to 19. These were TRIM15, HPGD, C1orf38, VNN2, IL-8, STAT1, CXCL10, LGALS3BP, TNFSF10, TNFRSF6, CCR1, OASL, HLA-B, HLA-G, HLA-DPA1, PLAUR, C3, BTN3A3 and GPR37. In particular, TRIM15, HPGD, C1orf38 and VNN2 were of interest because they were upregulated in both the virus vs. controls and PAF vs. controls. The following is a description of some of these genes which are of particular interest.

IL-8 (Interleukin 8) is of interest as the protein coded by this gene is a chemokine, one of the major mediators of the inflammatory response. This gene is believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis, a common respiratory tract disease caused by viral infection (9).

CXCL10 [Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand 10] encodes a chemokine that is one of the ligands for CXCR3. The binding of this protein to CXCR3 causes pleiotropic effects, including stimulation of monocytes, natural killer and T-cell migration, and modulation of adhesion molecule expression (9).

CCR1 [Chemokine (C-C motif) Receptor 1] encodes a member of the beta chemokine receptor family. The ligands of this receptor include macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP-1 alpha), monocyte chemoattractant protein 3 (MCP-3) and myeloid progenitor inhibitory factor-1 (MPIF-1). Chemokines and their receptors are critical for the recruitment of effector immune cells to the site of inflammation (9).

C3 (Complement Component 3) plays a central role in the activation for both the classical and alternative complement activation pathways. Individuals with C3 deficiency are susceptible to bacterial infections (9).

Discussion

The development of DNA microarray assays has provided the possibility of studying inflammatory responses from a totally new viewpoint. Previous gene expression studies conducted on airway epithelial cells have focused on a single inflammatory agent, assuming that the cellular responses would be uniform and standard (10–14). However, it is now possible to take a global view of the inflammatory process by looking for changes in gene expression, without necessarily knowing the precise function of the genes showing altered expression [(15), this study]. Two intriguing possibilities arise from this approach. First, previously unsuspected genes can be identified as playing a role in the cellular inflammatory responses. Second, it provides the possibility to develop a rapid assay for assessing anti-inflammatory activity of biologically active compounds, including naturally derived products. By identifying a panel of 40–50 proteins that consistently show changes in expression, we can develop a western-blot based quantitative assay. Initial identification of candidate proteins is far quicker using DNA microarray techniques.

Our previous work on the variability in [Ca2+]i signaling strongly implies that there are different inflammatory responses mounted by airway epithelial cells. These responses can be very short-lived [as seen with bradykinin stimulation; (16,17)], have a moderate duration [as seen with histamine stimulation; (17,18)], or be much longer lived [as seen with ATP stimulation; (19,20)]. PAF (maximal concentration 10 µM) stimulates a markedly different change in [Ca2+]i. Rather than a rapid rise, [Ca2+]i increases relatively slowly over the first 2–3 min of exposure, reaching a plateau which persists for the duration of exposure to PAF (Harris, unpublished data). The magnitude of this plateau is comparable with the peak elicited during stimulation with ATP (17–19), BK (16,17) or histamine [>1500 µM; (17,18)] and is maintained for long duration, making it an ideal choice to provoke the inflammatory response. Furthermore, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that PAF plays a significant role in mediating airway inflammation (21–28). In this study, our focus was on the long-term cellular inflammatory responses involving changes in gene expression. These are the types of inflammation which would be provoked during a viral infection, such as rhinovirus or influenza (29,30).

Bioinformatics is commonly referred to as the task of organizing and analyzing complex data resulting from modern molecular and biochemical techniques (31). Computers make it possible to manage this increasing amount of data. In addition, the advent of the Internet has allowed for the fast and free flow of information. It has become a vital tool for scientists because it allows for the sharing of information contained in centralized databases.

A number of databases were searched to retrieve the information needed to properly analyze the gene expression profiles obtained from the Affymetrix Microarray Suite Software. Information was obtained for the expressed genes from four comparison groups: virus vs. controls increases, virus vs. controls decreases, PAF vs. controls increases and PAF vs. controls decreases. The Affymetrix Probe Set ID codes, which represent the expressed genes from the Affymetrix microarray analysis, were deciphered using the Ensembl database. The Ensembl server produces and maintains an automatic annotation database on eukaryotic genomes. It is the result of a joint project between the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) and the Sanger Institute. Ensembl is capable of automatically tracking gene sequences of the human genome and assembling and analyzing them to identify genes and other features of interest (32). For this study, Ensembl was able to correspond the gene name with the Affymetrix code.

Once the gene names were known, other databases could then be searched for additional information about the genes. One useful database was the Source database. Its main advantage is its user-friendly interface and that it combined data from many data sources. The Source database brings together information from a broad range of resources and provides it in a manner particularly useful for analyses. Source's GeneReports include gene aliases, chromosomal location, functional descriptions, GeneOntology annotations, gene expression data and links to external databases. Biological roles and summary of functions are based on information from the LocusLink database and the SwissProt database. GeneOntology annotations provide information on the biological process, molecular function and cellular component of the protein. In addition, the Source database provides links to outside databases containing gene information ranging from their mapped coordinates within the genome to enzymatic function of the proteins they code for. These linked databases include Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), LocusLink, UniGene, GenAtlas, GeneCard, and Ensembl. A useful feature of the source database is its ability to extract data for a batch set of genes; thereby allowing for the efficient retrieval of information for many genes at once. A batch search is done using either the gene's clone ID, accession number, gene name, gene symbol, UniGene ID, or LocusLink ID. These are then uploaded to the server via a text file. Since many of the resources on which the database is based are frequently updated, the Source database is re-loaded on a weekly basis to ensure that it contains the most up-to-date information (33). In order to aid analysis, the genes were organized according to biological process and molecular function based on the GeneOntology annotations. GeneOntology annotations are organized by the Gene Ontology Consortium, which provides consistent descriptions of gene products in different databases.

The OMIM database was used to obtain a more detailed summary of the expressed genes. OMIM is a comprehensive knowledge base of human genes and genetic disorders compiled to support research and education in human genomics. It is considered to be a phenotypic companion to the human genome project. OMIM is written and edited at Johns Hopkins University with input from scientists and physicians around the world (34). It was started by Dr Victor A. McKusick and is available on the Internet via the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The NCBI, along with the European Bioinformatic Institute (EBI), provides many of the bioinformatic tools and databases available on the Internet. The OMIM database can be searched by MIM number, disorder, gene name or gene symbol. The limits function may be used to perform a restricted search. Each OMIM entry has a full-text summary of a gene with links to literature references, sequence records, gene location and related databases. Links to literature references throughout the gene summary are particularly useful in providing further detail of the information presented.

Viral infections have many effects on the airways including potentiation of the airway response to tachykinins, an increase in vagally mediated reflex bronchoconstriction, and the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells (1). In direct response to viral products, airway epithelial cells can initiate inflammatory cascades by generating cytokines (35). Airway epithelial cell responses to inflammatory mediators can also invoke local cytokine networks by initiating synthesis and release of interleukins, chemokines, colony stimulating factors and growth factors (5). Cytokines communicate in a paracrine manner with infiltrating inflammatory cells and airway cells (1). Inflammation is a localized protective response, which can be induced by microbial infection; therefore, upregulation of genes that have an antimicrobial function or are involved in the immune response is probable (35). Inflammation is also associated with excessive airway secretions, which may involve the upregulation of receptors (1). In addition, a number of pathways involving cAMP and protein kinase may be activated during an inflammatory response.

The initiation of the inflammatory response resulted in changes in human bronchial epithelial cell gene expression which were monitored using Affymetrix GeneChip probe arrays. Once all the information was compiled and analyzed, the next step was to choose a set of proteins to serve as indicators for changes in airway inflammation. Genes of interest were those that function as receptors, cytokines, interleukins, antimicrobials and were involved in either the inflammatory response, immune response, transport processes or protein kinase pathways. Cytokines and interleukins were of interest because they are synthesized and secreted by airway epithelial cells during the inflammatory response.

After completing analysis of the gene expression data, the total number of expressed proteins that may potentially act as a marker for monitoring the modulation of airway inflammation was narrowed to 19. Further studies will involve selecting antibodies for these proteins, culturing airway epithelial cells in the presence of extracts of natural health products, extracting the proteins and identifying them via western blot electrophoresis.

Figure 1.

AffymetrixGeneChip expression analysis.

Table 1.

Proteomic databases utilized

| Ensembl | http://www.ensembl.org |

| Source database | http://source.stanford.edu |

| Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) | http://http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?dp=OMIM |

| National Center for Biotechnology Information | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| European Bioinformatic Institute | http://www.ebi.ac.uk |

| SwissProt database | http://www.expasy.org/sprot/ |

| Gene Ontology Consortium | http://www.geneontology.org/ |

Acknowledgments

The funding for this project was provided by the David Collins Dawson Endowment Fund and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Summer Student Program.

References

- 1.Turner RB. The Treatment of Rhinovirus Infections: progress and potential. Antiviral Res. 2001;49:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(00)00135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Hara M, Kiefer D, Farrell K, Kemper K. A review of 12 commonly used medicinal herbs. Arch Family Med. 1998;7:523–36. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shelhamer JH, Levine SJ, Wu T, Jacoby DB, Kaliner MA, Rennard SI. Airway Inflammation. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:288–304. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst E. The risk-benefit profile of commonly used herbal therapies: Ginkgo, St John's Wort, Ginseng, Echinacea, Saw Palmetto, and Kava. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:42–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-1-200201010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine SJ. Bronchial epithelial cell-cytokine interactions in airway inflammation. J Investig Med. 1995;43:241–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schadt EE, Li C, Su C, Wong WH. Analyzing high-density oligonucleotide gene expression array data. J Cell Biochem. 2001;80:192–202. http://microarray.mbg.jhmi.edu/Trizol.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipshutz TJ, Fodor SPA, Gingeras TR, Lockhart DJ. High density synthetic oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Genet. 1999;21(Suppl. 1):20–4. doi: 10.1038/4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Affymetrix (2003) Genechip expression analysis technical manual. affymetrix http://www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/manual/expression_manual.affx. [Google Scholar]

- 9.LocusLink Database National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/LocusLink/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiba Y, Kusakabe T, Kimura S. Decreased expression of uteroglobin-related protein 1 in inflamed mouse airways is mediated by IL-9. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L1193–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00263.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Thai P, Zhao YH, Ho YS, DeSouza MM, Wu R. Stimulation of airway mucin gene expression by interleukin (IL)-17 through IL-6 paracrine/autocrine loop. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17036–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamid Q. Effects of steroids on inflammation and cytokine gene expression in airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:636–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01792-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper P, Potter S, Mueck B, Yousefi S, Jarai G. Identification of genes induced by inflammatory cytokines in airway epithelium. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:L841–52. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeffery PK. Laitinen A. Venge P. Biopsy markers of airway inflammation and remodelling. Respiratory Med. 2000;94(Suppl F):S9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(00)90127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwiebert LM, Mooney JL, Van Horn S, Gupta A, Schleimer RP. Identification of novel inducible genes in airway epithelium. Am J Respiratory Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:106–13. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.1.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris RA, Baimbridge KG, Bridges MA, Phillips JE. Effects of various secretagogues on [Ca2+]i in cultured human nasal epithelial cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;69:1211–1216. doi: 10.1139/y91-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris RA, Hanrahan JW. Histamine stimulates a biphasic calcium response in the human tracheal epithelial cell line CF/T43. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C781–C791. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.3.C781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris RA, Hanrahan JW. Effects of EGTA on calcium signalling in airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C1426–C1434. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason SJ, Paradiso AM, Boucher RC. Regulation of transepithelial ion transport and intracellular calcium by extracellular ATP in human normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1649–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb09842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris RA, Pon DJ, Katz S, Hanrahan JW. Intracellular calcium responses in CF/T43 cells: calcium pools and influx pathways. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:363–73. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.2.L363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cozens AL, Yezzi MJ, Chin L, Simon EM, Finkbeiner WE, Wagner JA. Characterization of immortal cystic fibrosis tracheobronchial gland epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5171–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamaoki J, Sakai N, Isono K, Kanemura T, Yamawaki I, Takizawa T. Effects of platelet-activating factor on bioelectric properties of cultured tracheal and bronchial epithelia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:1042–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)92148-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers DF, Alton EW, Aursudkij B, Boschetto P, Dewar A, Barnes PJ. Effect of platelet activating factor on formation and composition of airway fluid in the guinea-pig trachea. J Physiol. 1990;431:643–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karasen RM. Uslu C. Gundogdu C. Taysi S. Akcay F. Effect of WEB 2170 BS, platelet activating factor receptor inhibitor, in the rabbit model of sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:477–82. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson WR, Jr, Lu J, Poole KM, Dietsch GN, Chi EY. Recombinant human platelet-activating factor-acetylhydrolase inhibits airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in mouse asthma model. J Immunol. 2000;164:3360–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longphre M, Zhang L, Harkema JR, Kleeberger SR. Ozone-induced pulmonary inflammation and epithelial proliferation are partially mediated by PAF. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:341–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldie RG, Pedersen KE. Mechanisms of increased airway microvascular permeability: role in airway inflammation and obstruction. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22:387–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto K, Hashimoto S, Gon Y, Nakayama T, Horie T. Proinflammatory cytokine-induced and chemical mediator-induced IL-8 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:825–31. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi AM, Jacoby DB. Influenza virus A infection induces interleukin-8 gene expression in human airway epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1992;309:327–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80799-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ieki K, Matsukura S, Kokubu F, Kimura T, Kuga H, Kawaguchi M, et al. Double-stranded RNA activates RANTES gene transcription through co-operation of nuclear factor-kappaB and interferon regulatory factors in human airway epithelial cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:745–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rashidi HH, Buehler LK. Bioinformatics Basics: Applications in Biological Science and Medicine. CRC Press, New York; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayat A. Bioinformatics: science, medicine, and the future. BMJ. 2002;324:1018–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7344.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diehn M, Sherlock G, Binkley G, Jin H, Matese JC, et al. Source: a unified genomic resource of functional annotations, ontologies, and gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:219–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger J, Bocchini C, Valle D, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:52–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pettersen CA, Adler KB. Airways Inflammation and COPD. Chest. 2002;121:142S–150S. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5_suppl.142s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]