Abstract

In the course of an ethnobotanical study on fungi used in Yemeni ethnomedicine the fungus Podaxis pistillaris (Podaxales, Podaxaceae, Basidiomycetes) was found to exhibit antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococcus flavus, Bacillus subtilis, Proteus mirabilis, Serratia marcescens and Escherichia coli. In the culture medium of P. pistillaris three epidithiodiketopiperazines were identified by activity-guided isolation. Based on spectral data (NMR, ESI-MS and DCI-MS) their identity was established as epicorazine A (1), epicorazine B (2) and epicorazine C (3, antibiotic F 3822), which have not been reported as constituents of P. pistillaris previously. It is assumed that the identified compounds contribute to the antibacterial activity of the extract.

Keywords: Epicorazines, antibacterial, cytotoxic, Yemen

Introduction

In our continuing study of plants and fungi used in traditional medicine in Yemen (1–5), we selected the fungus Podaxis pistillaris (L. Pers.) Morse agg. for an in depth investigation. This fungus is spread in semideserts of Africa, Asia, Australia and America. In Yemen it can be found in arid zones. No species of this genus has been found in Europe and Japan (6).

The fruiting bodies of P. pistillaris are used in some parts of Yemen for the treatment of skin diseases, in South Africa as folk medicine against sunburn and in China to treat inflammation (5,7,8). In other countries, e.g. India, Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, they are used as food (9,10). In Australia, the fungus was used by many desert Aborigines to darken the white hair in the whiskers of old men, for body painting and as a fly repellent (11). The fruiting bodies are known to be rich in proteins containing all essential amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids and minerals (12). Antimicrobial activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Proteus mirabilis have been found (13). On the other hand, there is information from Nigeria and South Africa about a possible toxicity (14). A high value for total lanthanides was measured in this mushroom (75 mg kg−1 dry weight) (15). Cultivation assays of the fruiting bodies have been successful (16,17). But no phytochemical studies of P. pistillaris have been reported till now.

In order to get enough and reproducible material for phytochemical and biological studies we established mycelial cultures of P. pistillaris, expecting that the cultures will produce the same metabolites as the fruiting bodies. Here, we report on the antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of extracts and isolated metabolites, the isolation of three antibacterial epicorazines from the culture medium and the possible implications on safety.

Materials and Methods

General

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck) with the solvent EtOAc/toluene/HOAc (7:3:0.1). Chromatograms were inspected under UV light at wavelengths 254 and 366 nm, and by spraying with anisaldehyde–H2SO4 reagent. CC was carried out on Sephadex LH-20 (Pharmacia Biotech). IR spectra were recorded in KBr on a Perkin-Elmer FTIR 1650 spectrometer and UV spectra in MeOH with a Uvikon 930 spectrometer. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Spectrometer AM 400 with the solvent signal as internal reference. MS spectra were recorded on a Finnigan MAT 95 spectrometer (Finnigan MAT GmbH; Bremen), CD spectra on a circular dichrograph J-710 (Jasco Corp., Tokyo). Optical rotations were measured on a Perkin-Elmer 241 MC polarimeter at room temperature. M.p.s were recorded on a Kofler apparatus.

Fruiting Bodies

Fruiting bodies of P. pistillaris were collected from Aden region, Yemen, during the rainy season in February 1999. They were identified by Prof. H. Kreisel (Institute of Microbiology, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-University, Greifswald). A voucher specimen is deposited at the Department of Pharmaceutical Biology (Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität, Greifswald, Germany).

Pieces of the fruiting bodies were isolated and placed on solid HAGEM medium (18) in Petri dishes. After cultivation for 3 weeks at room temperature, the mycelium was removed from the agar plates and transferred into a liquid medium containing 5% glucose and 5% malt extract in distilled water adjusted to pH 5.4. The cultures were incubated for 3 weeks at 25°C on a rotary shaker (125 r.p.m.).

Extraction and Isolation

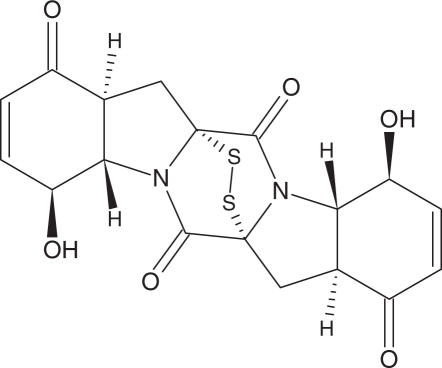

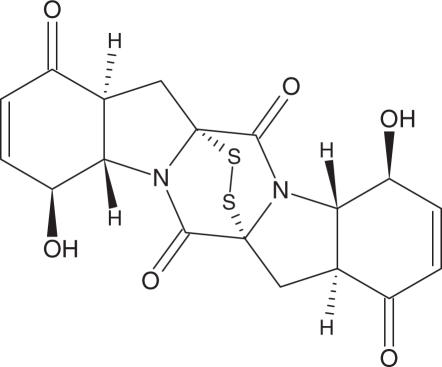

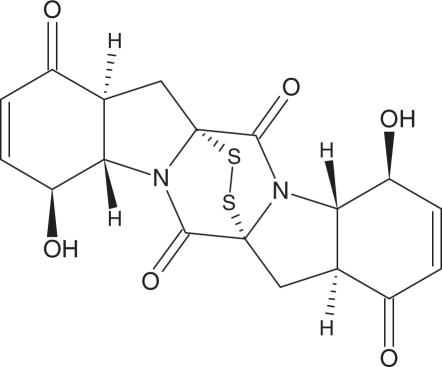

The culture medium was separated from the mycelium by filtration and extracted with ethyl acetate. The extract was dried over Na2S04 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting concentrate (0.5 g) was passed through Sephadex LH-20 using n-hexane/CH2C12 (1:2) as eluent to give five fractions (A–E). Fraction B (50 mg) was separated on a Sephadex LH-20 column with MeOH as the eluent to yield 2.5 mg of epicorazine A (1) (Fig. 1). Further purification of fraction C (30 mg) on Sephadex LH-20 with CH2Cl2/MeOH (2:1) yielded (1.5 mg) epicorazine B (2) (Fig. 2). Fraction E was separated on a Sephadex LH-20 column with CH2C12/MeOH (2:1) and yielded epicorazine C (3) (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Epicorazines A (1)

Epicorazin A (1), white crystals, melting point (mp) 197–198°C, TLC: EtOAc/toluene/HOAc (7:3:0.1) Rf = 0.72 (brown spot after spraying with anisaldehyde–H2SO4 reagent and heating); UV (MeOH) λmax (lg ɛ): 215 (4.42) and 260 (3.65) nm. IR (KBr) νmax: 3360, 1690, 1410, 1380, 1365, 1250, 1195, 1185, 1140, 1095, 1030 and 810 cm−1; NMR (Table 2); MS: EI-MS (200°C): m/z (%) = 420 (0.5) M+, 356 (100) (M − S2)−, (−)-DCI (NH3): m/z (%) = 420 (100) (M)−, 356 (22) (M − S2)−, (+)-DCI (NH3): m/z (%) = 438 (21) (M + NH4)+, 421 (5) (M + H)+, 357 (43) (M + H − S2)+, 296 (100).

Epicorazin B (2), white crystals, mp 192–193°C, TLC: EtOAc/toluene/HOAc (7:3:0.1) Rf = 0.65 (brown spot after spraying with anisaldehyde–H2SO4 reagent and heating); UV (MeOH) λmax (lg ɛ): 220 (2.83) nm. IR (KBr) νmax: 3450, 3360, 1690, 1670 and 1370 cm−1; NMR (Table 3); MS: EI-MS (200°C): m/z (%) = 356 (100) (M − S2)+, (−)-DCI (NH3): m/z (%) = 420 (100) (M)−, 355 (16) (M − H − S2)−,(+)-DCI (NH3): m/z (%) = 438 (7) (M + NH4)+, 110 (100).

Epicorazin C (3), glassy material, TLC: EtOAc/toluene/HOAc (7:3:0.1) Rf = 0.45 (brown spot after spraying with anisaldehyde–H2SO4 reagent and heating), NMR (Table 4); MS: EI (200°C): m/z (%) = 374 (91), 356 (100). (−)-DCI (NH3): m/z (%) = 438 (100), 420 (17), 373 (15). (+)-DCI (NH3): m/z (%) = 456 (100) (M + NH4)+, 150 (100).

Determination of Antibacterial Activity

The following bacterial strains were used: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213), Micrococcus flavus (SBUG 16), Bacillus subtilis (SBUG 14), P. mirabilis (SBUG 47), Serratia marcescens (SBUG 9) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922).

A modified agar diffusion method (19) was used to determine the antibacterial activity. Sterile nutrient agar (Immunpräparate, Berlin; 26 g l−1 agar in distilled water) was inoculated with bacterial cells (200 µl of bacterial cell suspension in 20 ml medium) and poured into Petri dishes to give a solid plate. An aliquot of 40 µl of test material dissolved in methanol (equivalent to 1 mg of the dried extract or 100 µg of pure compounds) was applied on sterile paper discs (6 mm diameter; Schleicher and Schuell, Ref. No 321860). Methanol was allowed to evaporate and the discs were deposited on the surface of inoculated agar plates. The plates were kept for 3 h in a refrigerator at 6°C to enable prediffusion of the substances into the agar and were then incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Ampicillin and gentamycin were used as positive and the solvent methanol as negative control. At the end of the incubation time inhibition zone diameters around each of the disc (diameter of inhibition zone minus diameter of the disc) were measured and recorded. An average zone of inhibition was calculated for the three replicates. An inhibition zone of 8 mm or greater was considered as good antibacterial activity.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were determined by standard serial broth microdilution assay in nutrition medium II (SIFIN, Berlin), starting from a 250 µg ml−1 solution. The end point in this assay was indicated by the absence of detectable growth after 18 h of incubation at 37°C.

Determination of Cytotoxic Activity

Cytotoxicity was measured by the neutral red uptake assay using FL-cells, a human amniotic epithelial cell line (1,20). Only living cells are able to manage the active uptake of neutral red. FL-cells were cultivated in a 96-well microtiter plate (105 cells per ml EAGLE-MEM, Sifin, Berlin; 150 µl per well) at 37°C in a humidified 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere. The EAGLE-MEM was completed by l-glutamine (0.1 g l−1), HEPES (2.38 g l−1), penicillin G (105 IE l−1), streptomycin sulfate (0.10 g l−1) and FCS (Gibco; 80 ml l−1). After 24 h, 50 µl of the solution of test substance or medium with equal amounts of ethanol (control) were added. After a further incubation for 72 h the cells were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution. An aliquot of 100 µl of neutral red solution (SERVA, 0.3% in EAGLE-MEM) was added per well. The cells were then incubated for 3 h at 37°C, followed by another three times washing with PBS. Hundred microliters of a solution of acetic acid (1%, v/v) and ethanol (50%, v/v) in distilled water were added. After shaking for 15 min the optical density was measured at 540 nm with an ELISA-Reader-HT II (Anthos Labtec Instruments, Salzburg). The mean of four measurements for each concentration was determined (n = 3). IC50 values (concentration that caused a 50% inhibition of growth compared with controls) were calculated with the help of micro cal. Origin program.

Results

Biological Activities

Unlike the extracts from the mycelium (DCM, EtOH, aqueous) the EtOAc extract from the culture medium of P. pistillaris showed a strong antibacterial activity against several Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (S. aureus ATCC 29213, M. flavus SBUG 16, B. subtilis SBUG 14, P. mirabilis SBUG 47, S. marcescens SBUG 9 and E. coli ATCC 25922; Table 1). Bioactivity-guided fractionation of this extract led to the isolation and structural elucidation of three pure substances (1–3) related to the antibacterial activity. The compounds were identified as epicorazines A, B and C (see below). In the agar diffusion assay the epicorazines are active against all bacteria tested (Table 1). The MIC against S. aureus is 25 µg ml−1 for epicorazine A (1), 50 µg ml−1 for epicorazine B (2) and 75 µg ml−1 for epicorazine C (3) (MIC ampicillin 0.05 µg ml−1). For a further evaluation of the biological activities of extract and isolated compounds their cytotoxicity was measured in the neutral red assay using cultivated human amnion epithelial cells (FL cells). All tested samples showed remarkable cytotoxicity. Ten microgram per milliliter of the extract caused the death of all FL cells. The IC50 against FL cells is 10 µg ml−1 for epicorazin A (1) and B (2).

Table 1.

Antibacterial activity of the EtOAc extract from the culture medium of Podaxis pistillaris and of epicorazines in agar diffusion assay

| Strain | Zones of inhibition (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOAc extract | Epicorazine A | Epicorazine B | Epicorazine C | Ampicillin | Gentamicin | |

| 1 mg per disk | 100 µg per disk | 10 µg per disk | ||||

| Staphyolococcus aureus ATCC 29213 | 30 ± 3 | 35 ± 4 | 30 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | 26 ± 2 | n.d. |

| Micrococcus flavus SBUG 16 | 20 ± 2 | 32 ± 3 | 30 ± 2 | 22 ± 2 | 31 ± 3 | n.d. |

| Bacillus subtilis SBUG 14 | 18 ± 2 | 35 ± 3 | 32 ± 3 | 20 ± 2 | 28 ± 3 | n.d. |

| Proteus mirabilis SBUG 47 | 19 ± 3 | 25 ± 2 | 24 ± 2 | 20 ± 2 | 30 ± 2 | n.d. |

| Serratia marcescens SBUG 9 | 18 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 | 20 ± 2 | 17 ± 2 | n.d. | 15 ± 2 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | 18 ± 1 | 25 ± 2 | 24 ± 3 | 18 ± 3 | n.d. | 14 ± 1 |

n.d. non detected; n = 9.

Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Epicorazines

Compound 1 was obtained as white crystals melting at 197–198°C. All well-resolved NMR signals of 1 in CDCl3 could be assigned and correlated by 1H, 1H-COSY, 1H, 13C-HMQC and 13C-HMBC NMR spectroscopy (Table 2), and thus provided the carbon skeleton from C-1 to C-9. DCI-MS spectrometry indicated a molecular mass of 420. This mass was rarely present in the EI mass spectrum, which was dominated by a fragment ion at m/z 356 corresponding to the loss of S2. With these data, 1 was recognized as the symmetrical epidithiodiketopiperazine antibiotic epicorazine A (1), previously isolated from the fungus Epicoccum nigrum (21). Comparison of our data with the 13C-NMR data of 1 in dioxane-d8 (10) and 1H-NMR data in acetone-d6 (22) confirmed this identification, including the same relative configuration, which was indicated by the vicinal coupling constants. Additionally, 1 furnished the same CD curve as given for epicorazine A (1) in (22) and thus showed that these compounds from different sources have the identical absolute configuration.

Table 2.

NMR-data of epicorazine A (1) in CDCl3 (1H: 300 MHz, 13C: 75 MHz)

| H | δH (p.p.m.) | m | J (Hz) | C | δC (p.p.m.) | m | HMBC-correlated H | δCa (p.p.m.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | — | — | 1 | 193.69 | s | 6, 7a, 5 (3) | 194.5 |

| 2 | 6.14 | dd | 2.4, 10.2 | 2 | 129.30 | d | 4-OH (163 Hz)b | 129.5 |

| 3 | 6.94 | dd | 1.9, 10.2 | 3 | 150.75 | s | 4-OH, 4 (165 Hz)b | 151.3 |

| 4 | 4.79 | ddt | 8.2, 1.6, 1.9 | 4 | 71.13 | d | 4-OH, 5, 6 | 71.3 |

| 4-OH | 5.84 | d | 1.3 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 5 | 3.81 | dd | 12.8, 8.2 | 5 | 69.43 | d | 6, 7b (3) | 69.9 |

| 6 | 3.26 | dt | 5.6, 12.8 | 6 | 48.97 | d | 7a+b (2, 5) | 49.2 |

| 7a | 3.03 | dd | 12.8, 14.8 | 7 | 31.08 | t | — | 31.0 |

| 7b | 2.59 | dd | 5.6, 14.8 | |||||

| — | — | — | — | 8 | 75.81 | d | 7a+b | 76.6 |

| — | — | — | — | 9 | 164.27 | s | 7a | 165.2 |

aIn dioxane see (20), the 1H-NMR data given by Deffieux et al. were obtained in acetone-dd, where several signals overlap especially at 90 MHz. According to our spectra their assignment of the partially overlapping 2- and 2′-protons has to be exchanged;

bdirekt 1JH,C coupling.

A second compound 2, isolated as white crystals melting at 192–193°C showed the same molecular mass and fragmentation behavior during mass spectrometry. It was identified as epicorazine B (2) (23) from its NMR data given in Table 3. Although the molecule halves are identical except their chirality, all 1H-NMR signals of 2 were well resolved at 400 MHz in CDCl3, and thus provided the complete proton coupling data indicating the relative configuration. The absolute configuration was confirmed by CD spectroscopy.

Table 3.

NMR data of epicorazine B (3)

| H | δHa (ppm) | m | J (Hz) | C | δCa (ppm) | m | HMBC-correlated H | δHb (ppm) | m | J (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | — | — | 1 | 193.70 | s | 6, 7a/b | — | — | — |

| 2 | 6.14 | dd | 10.3, 2.0 | 2 | 129.28 | d | — | 6.07 | dd | 10.3, 2.3 |

| 3 | 6.94 | dd | 10.3, 1.8 | 3 | 150.77 | d | 4-OH, 4 | 6.91 | dd | 10.3, 1.9 |

| 4 | 4.79 | ddt | 8.1, 1.8, 1.8c | 4 | 71.16 | d | 4-OH, 5, 6 | 4.77 | ddt | 8.5, 2.0, 2.0c |

| 4-OH | 5.88 | s | —c | — | — | — | — | 5.22 | s | —c |

| 5 | 3.79 | dd | 13.0, 8.1 | 5 | 69.51 | d | 7a/b, 6. 3 | 3.98 | dd | 13.1, 8.5 |

| 6 | 3.26 | dt | 5.7, 12.7 | 6 | 49.02 | d | 7a/b, 2 | 3.41 | dt | 5.8, 12.7 |

| 7a | 3.01 | dd | 15.0, 12.5 | 7 | 30.81 | t | 6 | 2.98 | dd | 14.5, 12.7 |

| 7b | 2.60 | dd | 15.0, 5.7 | 2.55 | dd | 14.5, 5.8 | ||||

| — | — | — | — | 8 | 76.19 | s | 7a/b | — | — | — |

| — | — | — | — | 9 | 164.67 | s | 7a | — | — | — |

| — | — | — | — | 1′ | 193.36 | s | 6′, 7′a/b | — | — | — |

| 2′ | 6.17 | dd | 10.4, 2.0 | 2′ | 128.41 | d | — | 6.11 | dd | 10.3, 1.1 |

| 3′ | 6.88 | dd | 10.4, 2.3 | 3′ | 148.77 | d | 4′ | 6.97 | dd | 10.3, 4.1 |

| 4′ | 4.90 | dd | 6.5, 2.4 | 4′ | 67.73 | d | 5′, 2′, 6′ | 5.23 | m | —c |

| 4′-OH | —d | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4.78 | d | 5.7 |

| 5′ | 4.68 | dd | 9.7, 6.5 | 5′ | 65.82 | d | 7′b, 3′, 6′ | 4.67 | dd | 7.2, 4.9 |

| 6′ | 3.38 | ddd | 9.7, 9.7, 8.0 | 6′ | 44.47 | d | 7′a/b, 2′ | 3.44 | ddd | 8.5, 7.2, 5.6 |

| 7′a | 2.60 | dd | 8.0, 14.6 | 7′ | 33.68 | t | 5′, 6′ | 2.55 | dd | 5.6, 14.4 |

| 7′b | 3.55 | dd | 9.7, 14.6 | 3.36 | dd | 8.5, 14.4 | ||||

| — | — | — | — | 8′ | 75.88 | s | 5′, 7′a/b | — | — | — |

| — | — | — | — | 9′ | 163.76 | s | 7′a/b | — | — | — |

aIn CDCl3 (1H: 400 MHz, 13C: 100 MHz);

bin acetone-d6 (600 MHz);

cbroad;

da corresponding OH signal was not observed.

Further traces of another variant 3 were isolated as glassy material. The molecular ion at m/z 438 suggested the formal addition of water. This was supported by the 1H-NMR spectra of 3 in DMSO-d6 and in DMSO-d6 with D2O for H/D exchange (Table 4), where one part of the molecule showed the signals known from 1 while the remaining 1H-NMR signals and their correlations from a 1H, 1H-COSY spectrum identified the other part of 3 as a saturated β-hydroxy-variant. Thus, 3 was recognized as epicorazine C, which has been isolated from Stereum hirsutum (24) and as antibiotic F 3822 from a strain of Epicoccum purpurascens (25). In order to designate the relative configuration, the coupling constants were studied. The sharp dd signal of 5′-H shows a coupling constant of 5 Hz with 4′-H and of 7 Hz with 6′-H. This indicates a cis-configuration of protons 5′-H and 6′-H. As in 1 the trans-configuration of protons 5-H and 6-H in the other part of 3 is evident by a coupling constant of 13 Hz. Biological activities of isolated compounds.

Table 4.

1H-NMR data of epicorazine C (3) (antibiotic F 3822)

| H | DMSOa | DMSO/(D2O)b | DMSOb,c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ | m | J (Hz) | δ | m | J (Hz) | δ | J (Hz) | |

| 2 | 6.07 | dd | 10, 2 | 6.06 | dd | 10.1, 2.0 | 6.05 | 10 |

| 3 | 6.90 | dd | 10, 2 | 6.89 | dd | 9.9, 1.8 | 6.88 | 10, 2 |

| 4-OH | 5.87 | s | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | 4.68 | d | 9 br. | 4.67 | ddd | 8.5, 2.2, 2.2 | 4.67 | 8, 2 |

| 5 | 3.98 | dd | 13, 8 | 3.94 | dd | 13.7, 9.2 | 3.96 | 13, 8 |

| 6 | 3.34 | ddd | 13, 12, 6 | 3.34 | ddd | 12.9, 12.6, 6.0 | 3.33 | 13, 12, 6 |

| 7b | 2.53 | m | —d | 2.54 | m | —d | 2.55 | 17, 5 |

| 7a | 2.84 | dd | 14, 12 | 2.84 | dd | 14.2, 12.7 | 2.86 | 14, 12 |

| 2′a | 2.70 | dd | 16, 10 | 2.70 | dd | 16.3, 10.2 | 2.69 | 17, 10 |

| 2′b | 2.53 | m | —d | 2.54 | m | —d | 2.51 | 14, 6 |

| 3′ | 3.71 | ddd | 10, 5, 5, 2 | 3.71 | ddd | 10.4, 4.3, 1.8 | 3.76 | 10, 5, 2 |

| 3′-OH | 5.14 | d | 5 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4′ | 4.78 | ddd | 5, 5, 2, 1 br | 4.77 | d | 4.6 br | 4.73 | 5, 2 |

| 4′-OH | 5.46 | d | 5 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 5′ | 4.40 | dd | 7, 5 | 4.41 | dd | 7.1, 4.6 | 4.43 | 8, 5 |

| 6′ | 3.17 | dddd | 8, 7, 2, 2 | 3.18 | ddd | 7.8, 7.5, 2.4 | 3.18 | 8, 3 |

| 7′a | 2.99 | dd | 15, 8 | 2.99 | dd | 14.2, 8.1 | 3.02 | 15, 8, 2 |

| 7′b | 2.79 | dd | 15, 2 | 2.79 | dd | 14.5, 2.3 | 2.79 | 15, 3 |

a600 MHz;

b400 MHz;

cJapan. Pat. 91-227 991;

doverlap of 2′b- and 7b-H.

Discussion

Herbal remedies used in the traditional folk medicine provide an interesting and still largely unexplored source for the creation and development of potentially new drugs (26). But it is necessary to reveal the active principles by isolation and characterization of their constituents and to validate their possible toxicity. Up to date, very little research was done to investigate the traditional medicinal plants and fungi in Yemen (1–4).

During our study of mycelial cultures of the widely used mushroom P. pistillaris, which has not been phytochemically investigated previously, its antimicrobial constituents were identified as epicorazines A (1), B (2) and C (3). These substances belong to the group of epipolythiopiperazine-2,5-diones (ETPs), an important class of biologically active metabolites produced only by fungi [reviewed in (26)]. They occur as monomers or dimers and are characterized by the presence of an internal disulphide bridge. Epicorazines could be found only in some strains of E. nigrum (21–23), E. purpurascens (25,27) and in S. hirsutum (24).

ETPs, their mostly investigated representative is gliotoxin, show a broad range of biological activities including antifungal, antibacterial and antiviral activities. In mammalian systems they display potent in vitro and in vivo immunosuppressive activity, induce apoptosis and possess anticancer activity. They may be produced in vivo during the course of fungal infections and contribute to the etiology of the disease. Gliotoxin appears to be a virulence factor associated with invasive aspergillosis of immunocompromised patients. The mode of actions of ETPs seems to be the inhibition of thiol requiring enzymes by covalent interaction to sulfhydryl groups of proteins and the formation of reactive oxygen species [reviewed in (25)].

The broad-spectrum of activities and the toxicity of most members of the ETP class ruled them out for clinical use as antimicrobial, immunosuppressive or anticancer agents till now.

With respect to the traditional medicine of Yemen our investigations confirm the biological activity and justify the ethnomedicinal use of P. pistillaris. We assume that the identified epicorazines contribute to the observed antibacterial effects of this mushroom. Because of cytotoxic and other undesired effects of epicorazines the results raise doubts about the usefulness of P. pistillaris as food (additive) and medicine. In vivo investigations of possible toxicity are strongly recommended. Such cautious are equally applicable to compounds derived from mushrooms (29) and white cedar (30).

Figure 2.

Epicorazines C (3)

Figure 2.

Epicorazines B (2)

References

- 1.Awadh Ali NA, Jülich WD, Kusnick C, Lindequist U. Screening of Yemeni medicinal plants for antibacterial and cytotoxic activities. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;74:173–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreisel H, Al-Fatimi MAM. Basidiomycetes and larger ascomycetes from Yemen. Feddes Report. 2004;115:547–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mothana R, Lindequist U. Antimicrobial activity of some medicinal plants of the island Soqotra. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96:177–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Fatimi MAM, Wurster M, Kreisel H, Lindequist U. Antimicrobial, cytotoxic and antioxidant activity of selected basidiomycetes from Yemen. Pharmazie. 2005;60:776–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Fatimi MAM. Universität Greifswald; 2001. Isolierung und Charakterisierung antibiotisch wirksamer Verbindungen aus Ganoderma pfeifferi Bres. und aus Podaxis pistillaris (L.: Pers.) Morse. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominguez de Toledo L. Gasteromycetes (Eumycota) del centro y oeste de la Argentina. I. Analisis critico de los caracteres taxonomicos, clave de generos y orden Podaxales. Darwiniana. 1993;32:195–235. (in Spain) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin H, Branch M. A Field Guide to the Mushrooms of South Africa. Cape Town, C. Strike 2nd Ed; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao XL. The Macrofungi in China. Zhengzou: Henan Science and Technology Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batra LR. Edible discomycetes and gasteromycetes of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Northwestern India. Biologia. 1983;29:293–304. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta S, Singh SP. Nutritive value of mushroom Podaxis pistillaris. Indian J Mycol Plant Pathol. 1991;21:273–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Australian National Botanic Gardens: Fungi Web Site. Available at www.aubg.gov.au/fungi/aboriginal.html.

- 12.Khaliel AS, Abou-Heilah AN, Kassim MY. The main constituents and nutritive value of Podaxis pistillaris. Acta Bot Hung. 1991;36:173–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panwar Ch, Purohit DK. Antimicrobial activities of Podaxis pistillaris and Phellorinia inquinans against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Proteus mirabilis. Mushroom Res. 2002;11:43–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alasoadura SO. Studies in the higher fungi of Nigeria. II: Macrofungi associated with termites. Nova Hedwigia. 1966;11:387–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stijve T, Andrey D, Lucchini GF, Goessler W. Simultaneous uptake of rare elements, aluminium, iron, and calcium by various macromycetes. Aust Mycol. 2001;20:92–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jandaik CL, Kapoor CN. Studies on vitamin requirements of some edible fungi. Indian Phytopathol. 1976;29:259–61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phutela RP, Kaur H, Sodhi HS. Physiology of an edible gasteromycete, Podaxis pistillaris (Lin. Ex Pers.) Fr. J Mycol Plant Pathol. 1998;28:31–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreisel H, Schauer F. Methoden des mykologischen Laboratoriums. Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1987. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer AW, Kirby WMM, Sheriss JC, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindl T, Bauer J. Jena, Berlin: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1989. Zell-und Gewebekultur. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baute MA, Deffieux G, Baute R, Neveu A. New antibiotics from the fungus Epicoccum nigrum. I. fermentation, isolation and antibacterial properties. J Antibiot. 1978;31:1099–101. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deffieux G, Baute MA, Baute R, Filleu MJ. New antibiotics from the fungus Epicoccum nigrum. II. Epicorazine A: structure elucidation and absolute configuration. J Antibiot. 1978;31:1102–5. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deffieux G, Filleu MJ, Baute R. New antibiotics from the fungus Epicoccum nigrum, II. Epicorazine B: structure elucidation and absolute configuration. J Antibiot. 1978;31:1106–9. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinwächter P, Dahse HM, Luhmann U, Schlegel B, Dornberger KJ. Epicorazine C, an antimicrobial metabolite from Stereum hirsutum HKI 0195. J Antibiot. 2001;54:521–5. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.54.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawashima A, Kishimura Y, Tamai M, Hanada K. Dithiodiketopiperazine compound. 02024166. Japanese patent Nr. 1990

- 26.Lindequist U, Niedermeyer THJ, Jülich WD. The pharmacological potential of mushrooms. eCAM. 2005;2:285–99. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardiner DM, Waring P, Howlett BJ. The epipolythiodioxopiperazine (ETP) class of fungal toxins: distribution, mode of action, functions and biosynthesis. Microbiology. 2005;151:1021–32. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown AE, Finlay R, Ward JS. Antifungal compounds produced by Epicoccum purpurascens against soil-borne plant pathogenic fungi. Soil Biol Biochem. 1987;19:657–64. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindequist U, Niedermeyer THJ, Jülich WD. The pharmacological potential of mushrooms. eCAM. 2005;2:285–299. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naser B, Bodinet C, Tegtmeier M, Lindequist U. Thuja occidentalis (Arbor vitae): A review of its pharmaceutical, pharmacological and clinical properties. eCAM. 2005;2:69–78. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]