Abstract

The sphinganine analog mycotoxin, AAL-toxin, induces a death process in plant and animal cells that shows apoptotic morphology. In nature, the AAL-toxin is the primary determinant of the Alternaria stem canker disease of tomato, thus linking apoptosis to this disease caused by Alternaria alternata f. sp. lycopersici. The product of the baculovirus p35 gene is a specific inhibitor of a class of cysteine proteases termed caspases, and naturally functions in infected insects. Transgenic tomato plants bearing the p35 gene were protected against AAL-toxin-induced death and pathogen infection. Resistance to the toxin and pathogen co-segregated with the expression of the p35 gene through the T3 generation, as did resistance to A. alternata, Colletotrichum coccodes, and Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. The p35 gene, stably transformed into tomato roots by Agrobacterium rhizogenes, protected roots against a 30-fold greater concentration of AAL-toxin than control roots tolerated. Transgenic expression of a p35 binding site mutant (DQMD to DRIL), inactive against animal caspases-3, did not protect against AAL-toxin. These results indicate that plants possess a protease with substrate-site specificity that is functionally equivalent to certain animal caspases. A biological conclusion is that diverse plant pathogens co-opt apoptosis during infection, and that transgenic modification of pathways regulating programmed cell death in plants is a potential strategy for engineering broad-spectrum disease resistance in plants.

Apoptosis, as a form of programmed cell death, is widely accepted as a requirement for development of many multicellular organisms, including mammals, insects, and nematodes (1), and also plays an important role in many diseases of these organisms (2, 3). Numerous animal diseases occur as a result of induction of cell death to facilitate infection, suppression of cell death until colonization is achieved, or the induction of cell proliferation in the case of several cancers. In addition, dysregulation of apoptotic pathways by some tumor viruses leads to the induction of cell proliferation and cancer (4). In plants, programmed cell death is now emerging as a major player in disease, and the dying cells exhibit many of the morphological characteristics of apoptosis as defined in animal systems (5, 6).

Genes that function in the induction or suppression of apoptosis have been identified in a variety of organisms from human to insect to nematode. For example, the baculovirus protein p35 (3, 7, 8) has been shown (9, 10) to inhibit members of a family of cysteine proteases, called caspases, during viral replication in host cells. This inhibition prevents caspase-mediated cleavage of several substrates that are important for cellular homeostasis, and thereby blocks death of the infected cells until viral replication is complete. The specificity of the p35 protein is resident in a tetrapeptide sequence, DQMD, that binds to the active site of the target caspase. The mechanism of p35 action appears to involve a direct interaction with the active site of the target caspases and is a potent caspase-specific inhibitor (11). Regulation of caspases by molecules that either inhibitor or activate caspases constitutes a major basis for the control of apoptosis and is being studied widely for potential strategies to control disease. The expression of signal molecules by potential pathogens that functionally co-opt these regulatory mechanisms can trigger either death or proliferation to favor pathogenesis. In vivo expression of p35 in transgenic systems results in delay of death caused by both developmental and pathological signals in mammals (12, 13), insects (8, 14), and nematodes (15, 16). A recent report also indicates that expression of p35 by Agrobacterium tumefaciens reduced the onset of apoptosis in embryonic maize callus compared with control callus (17).

In plants, apoptosis occurs by mechanisms that appear morphologically similar to that of animals (18–20). However, to date no apoptosis-regulating genes that share functional or sequence similarity to those characterized in animals have been isolated from plants. However, transgenic expression in plants of known apoptosis-regulating genes from animals can identify functionally coupled apoptotic systems in plants (21). One system we have used to identify morphological markers of apoptosis in plants and to look for genetic markers of disease-dependent programmed cell death is the Alternaria stem canker disease of tomato caused by Alternaria alternata f. sp. lycopersici (Aal). Cell death, symptomatic of this disease, results from expression by Aal of host-selective mycotoxins (AAL-toxin) that inhibit ceramide synthase, and, by mechanisms that are unclear, trigger cell death. Only strains of Aal that produced the toxins are pathogenic on nonsenescent tomato tissue (22), and only cultivars of tomato homozygous for the recessive alleles (asc/asc) at the Asc locus are sensitive to the toxins and susceptible to Aal (23).

AAL-toxin and chemical congeners produced by Fusarium moniliforme (fumonisins) have been shown by us and others to induce apoptosis in animal cells (18, 24). The induction of cell death in both animal and plant cells by fumonisins and AAL-toxin occurs at similar toxin concentrations (10–50 nM) and follows similar time frames (12–24 h). Morphological markers including terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated biotinylated-dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells, DNA ladders, Ca2+-activated nucleosomal DNA cleavage that was inhibited by Zn2+, and the formation of apoptotic-like bodies, characteristic of apoptosis, were observed in both the tomato and monkey kidney (CV-1) cells (18–20, 24, 25).

In this report, we provide evidence that in vivo expression of the baculovirus p35 gene effectively blocks apoptotic cell death as induced by either a host-selective toxin or any of several necrotrophic pathogens, leading to protection against the disease caused by these pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Constructs and Plant Transformation.

Transgenic tomato plants were produced by A. tumefaciens strain LBA4404 mediated transformation. The coding region of the baculovirus gene p35 (7) was cloned into a binary plant transformation vector by using a Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter for expression. Using the same binary construct as above, tomato “hairy roots” were produced by Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain ATCC 15834 mediated transformation of tomato cotyledons essentially according to ref. 26. The DRIL p35 mutant was generated by PCR with the wild-type p35 sequence as template to convert the amino acid sequence DQMD78 in wild-type p35 into the amino acid sequence DRIL78. The D78 is required for the inhibition of caspase activity (27). Additional details can be found in Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Northern Analysis.

Total leaf RNA, isolated by Trizol reagent (GIBCO/BRL), was analyzed for p35 transcript by Northern blot using labeled p35 coding sequence as probe. The results showed that high levels of p35 mRNA are present in all of the transgenic plants containing the p35 construct. Messenger RNA, isolated from untreated p35 transgenic tomato leaves, was shown not to contain induced pathogen-related (PR) transcripts homologous to PR-1 by probing a Northern blot with the tomato P4 gene (28).

Pathogenicity Assays.

Additional details can be found in Supporting Methods.

Aal.

This forma specials of A. alternata causes the Alternaria stem canker disease of tomato and secretes the host-selective AAL-toxins as primary chemical determinants of the disease (29). This pathogen can infect leaves, stems, green fruit, and ripe fruit of tomato, causing localized cell death from which the fungus spreads in each case. Spore concentrations of 1 × 104, 1 × 105, and 1 × 106 spores per ml were used to assess the dosage-dependent contribution of p35 to resistance.

A. alternata.

The strain of A. alternata that causes the black mold disease of tomato does not produce any detectable AAL-toxin, can only infect ripening tomato fruit (22), and has no known genetic resistance. Inoculation of ripening tomato fruit was by pin prick through a droplet containing 1 × 105 spores per ml. This insured that 100% of the inoculated sites resulted in an infection in control fruit. Lesions developed as blackening circular depressions. Mean lesion diameter of lesions on p35-expressing fruit was compared with mean lesion diameter on susceptible control fruit.

Colletotrichum coccodes.

Assays with C. coccodes were performed on ripe fruit by the same method as used for A. alternata. C. coccodes is known to require a wound site to infect ripe fruit (30). Mean lesion diameter of lesions on p35-expressing fruit was compared with mean lesion diameter on susceptible control fruit.

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst).

Greenhouse-grown tomato plants used for inoculations were four to 6 weeks old and had six to eight expanded leaves. Pst grown overnight in Kings B media, was adjusted to 1 × 104 colony-forming units per ml. Six control plants and six p35 transgenic T3 homozygous plants were inoculated by vacuum infiltration as follows: soil was covered with plastic wrap and the potted plants were inverted into a beaker containing the inoculum and fully immersed in the beaker, which was placed in a vacuum chamber and subjected to −101 kPa for 2 min. The vacuum was released slowly over a 10-min period to allow for bacterial infiltration with no detectable mechanical damage to the tissue.

p35 Assays.

Western blot analysis was performed on A. tumefaciens cell lysate (15 μg of protein) separated by PAGE and blotted onto Immobilon PVDF membrane. The p35 protein was detected using a polyclonal rabbit antibody (a gift of Promega). The inhibitory effect of heterologously expressed p35 on caspase activity was determined with a Caspase-3 assay kit (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) by using the colorimetric substrate Ac-DEVD-pNA according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

Results

Expression of p35 in Tomato Cells Protects Against Toxin-Induced Death.

Tomato plants of the genotype (asc/asc) were genetically modified to overexpress the baculovirus p35 gene. Ten primary transformants (T1 lines) contained p35 mRNA transcripts, as assessed by Northern analysis, and were resistant to 250 nM AAL-toxin, whereas control plants died at 50 nM AAL-toxin (data not shown).

Although T1 plants were morphologically normal, eight expressed varying levels of sterility, whereas two of the T1 lines were completely fertile. The infertility of eight of the asc/asc p35 transformed lines appears to be specific for the asc/asc genotype. We transformed two other tomato genotypes (Asc/Asc and VFNT cherry), as well as Arabidopsis, and have found that these lines have normal fertility but also exhibit reduced disease phenotypes (data not shown). To verify that this reduced cell death phenotype is due to expression of the p35 gene and not mutagenesis unrelated to p35 expression, we tested the effect of p35 expression in tomato hairy roots.

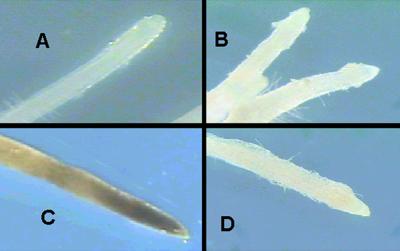

Tomato hairy roots transformed by A. rhizogenes to express the p35 gene (detected by genomic PCR) were assayed by transferring a 2-cm piece of root onto media containing 0, 50, 250, or 500 nM of AAL-toxin. After 7 days, the control root tips (transformed with vector alone) had browned and died on plates containing as low as 50 nM AAL-toxin, whereas five independent p35 transgenic roots survived up to 500 nM with no signs of death (Fig. 1).

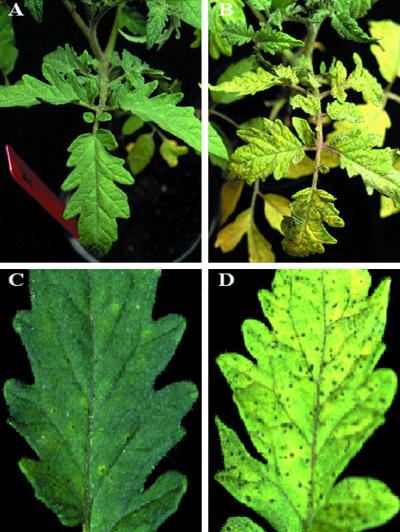

Fig 1.

AAL toxin sensitivity in p35 hairy roots. Transgenic roots were transferred to media with and without TA toxin for 7 days before microscopy. Shown is one representative of the protective phenotype of p35. (A) asc/asc transformed with empty vector; no toxin. (B) asc/asc transformed with p35; no toxin. (C) asc/asc transformed with empty vector; 250 nM TA toxin. (D) asc/asc transformed with p35; 250 nM TA toxin.

Effect of the DRIL Mutation on Biological Activity of p35.

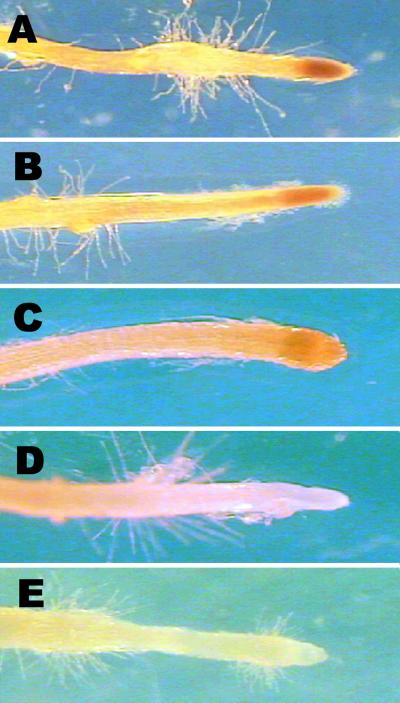

The crystal structure of p35 has recently been published (31), along with evidence that the mode of caspase inhibition by p35 is resident in a prominent loop in the globular protein, referred to as the “basket handle.” The anticaspase activity of p35 depends on the ability of the caspase to bind the tetrapeptide DQMD78 in the basket handle of p35 and cleave after D78 resulting in a conformational change in the p35 protein that renders it unable to leave the active site of the caspase. The cleavage of p35 thus results in a suicide inhibition of the caspase. Mutations in the basket handle that interfere with this cleavage render p35 inactive against caspases (15). We have taken advantage of this to demonstrate that the DQMD78 is critical for the activity of p35 in tomato by constructing a mutant p35 with DRIL78 sequence substituted for the DQMD78 sequence. Unlike wild-type p35, this mutant, called p35 DRIL, has no in vitro activity against caspase-3 when expressed from Escherichia coli (data not shown). The p35 DRIL was expressed in hairy roots by A. rhizogenes transformation and verified by genomic PCR. Fig. 2 demonstrates that p35 DRIL hairy roots were killed by 250 nM TA toxin just like empty vector hairy roots, whereas a p35 wild-type hairy root was completely protected. This shows that the antiapoptotic phenotype of p35 in tomato requires the same sequences as the animal anticaspase activity. These data strongly support the hypothesis that the activity of p35 in tomato, as in animal systems, is the result of inhibition of caspase-like proteases.

Fig 2.

AAL toxin sensitivity in p35 DRIL mutant hairy roots. Transgenic roots were transferred to media with 500 nM TA toxin for 7 days before microscopy. (A) asc/asc p35 DRIL #1. (B) asc/asc p35 DRIL #26. (C) asc/asc empty vector. (D) Asc/Asc empty vector. (E) asc/asc transformed with wild-type p35.

To understand the effect of p35 expression in whole tomato plants, one of the asc/asc fertile lines, designated 114-2, shown by Southern analysis to have one insertion locus of the p35 gene (data not shown), was chosen for further study. Leaflets from 114-2 plants showed almost no toxin-induced cell death when treated with up to 250 nM TA toxin, whereas the untransformed asc/asc control leaflets displayed extensive, concentration-dependent cell death with 100 nM TA toxin and higher concentrations (see Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

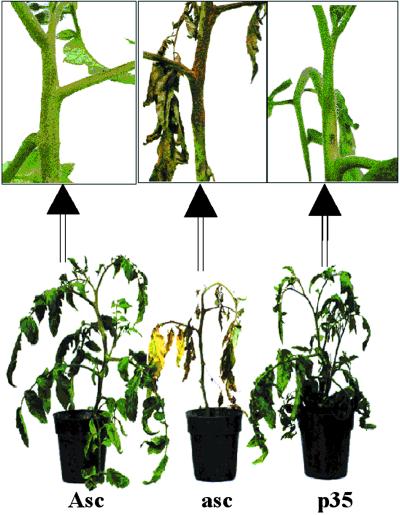

Given the host-selective nature of AAL-toxin, we reasoned that decreased toxin sensitivity would translate into decreased disease symptoms caused by the toxin-producing fungus, Aal. The ability of the 114-2 tomato plants to resist fungal infection was tested by challenging a population of sixty-four T2 plants (progeny from the self of the T1 plant) with Aal fungal spores. At 21 days postinoculation, 16 plants showed a marked decrease in both the number and size of fungal lesions, 32 plants showed somewhat decreased disease symptoms, and 16 plants showed normal disease symptoms. Representative examples of these phenotypes are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig 3.

Expression of p35 and pathogenicity of Aal fungus. Conidia of Aal (1 × 105 conidia per ml) were brushed down the entire length of one side of the stem with a camelhair brush. After 2 days in a moist chamber (98–100% RH), plants were removed to the greenhouse and photographed 21 days after inoculation. Genotypes shown are Asc/Asc empty vector (Asc); asc/asc empty vector (asc); and asc/asc p35 homozygote (p35).

RNA analysis of these 64 plants revealed that 51 of the 64 plants expressed p35 transcript (data not shown). The pathogen likely overwhelmed the protective influence of p35 in some hemizygote plants, which would account for the discrepancy between the number of plants lacking p35 and the number of plants with normal disease development. These segregation ratios, along with the Southern analysis, indicated that p35 protection against Aal is inherited as a simple Mendelian trait. All susceptible controls (untransformed asc/asc, GUS-transformed asc/asc, and p35-transformed segregants negative for p35 mRNA) supported normal levels of the disease and were dead within 7 days after inoculation.

Expression of p35 Protects Against Pathogen-Induced Death.

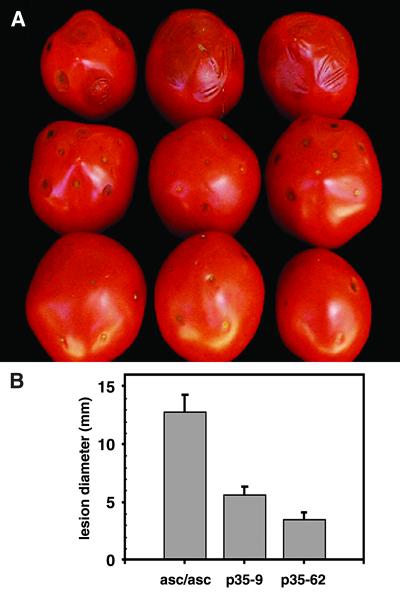

To investigate the ability of the p35 gene to protect against other fungal pathogens, we looked at A. alternata, the causal agent of black mold disease in tomato. This close relative of Aal does not produce any known toxins and only infects ripening fruit. We tested the ability of the p35 gene to limit lesions on ripening tomato fruit expressing p35. Interestingly, the results show that the size of the lesions is at least 50% smaller in p35-expressing fruit than in control fruit (Fig. 4), and in some cases they were free of black mold symptoms. This means that p35 expression provides postharvest protection against this fungal necrotroph. It should be noted that no other known simply inherited genetic resistance to black mold exists in tomato. Temporal resistance, in the form of an almost 50% reduction in lesion expansion rates over a 5 day period in lines expressing p35, was observed against C. coccodes, another colonizer of ripe fruit for which no known natural resistance exists (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Expression of p35 and pathogenicity of black mold. Five microliters of A. alternata conidia (1 × 106 conidia per ml) were inoculated on needle wounds made in the surface-sterilized pericarp of greenhouse-grown ripe fruit. Inoculated fruit was placed in high-humidity plastic boxes. Measurements began once lesions appeared. (A) Three fruit each of control asc/asc empty vector (top row) and two p35 T2 transgenic lines (bottom two rows) were tested for susceptibility to A. alternata. (B) Lesions were measured across the same diameter for 3 consecutive days. Data shown are from three independent experiments.

We next tested the ability of p35 expression to restrict disease progression caused by Pst, the causal agent of bacterial speck disease in tomato. Tomato plants expressing p35 were shown to be markedly protected from Pst-induced lesion formation when compared with control plants (Fig. 5 A and B). Expression of p35 results in both fewer and smaller lesions (Fig. 5 C and D). Analysis of the growth of Pst in tomato leaflets showed that the amount of bacteria in a leaflet is proportional to the lesion area, and that the amount of bacteria in 114-2 plants was 10-fold less than control plants (Table 1). These findings suggest that p35 expression slows the growth of the Pst bacteria, thereby lessening disease symptoms (spots of dead cells). These data are consistent with our previous report, where co-infiltration of Pst with the peptide Ac-DEVD-CHO (a caspase inhibitor) blocked cell death and disease in an otherwise compatible interaction (32).

Fig 5.

Expression of p35 and pathogenicity of Pst. Greenhouse-grown tomato plants were inoculated by vacuum infiltration with Pst T1 strain [1 × 104 colony-forming units (cfu) per ml] and kept at 22°C for 5 days. (A) asc/asc p35 homozygote. (B) asc/asc empty vector. (C) Detail of asc/asc p35 homozygote. (D) Detail of asc/asc empty vector. Entire leaflets were ground in buffer to determine growth (cfu per ml) of bacteria for each leaflet.

Table 1.

Effect of p35 expression on lesion size and number caused by Pst

| Genotype | asc/asc | p35/p35 |

|---|---|---|

| Leaflet mass, g | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| Leaflet area, cm2 | 33.9 ± 1.9 | 37.9 ± 2.6 |

| Lesions per leaflet | 106.3 ± 9.9 | 31.4 ± 4.9 |

| Lesion area, cm2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.01 |

| Lesions per leaflet area | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| Lesion area per leaflet area | 0.02 ± 0.002 | 0.0025 ± 0.0004 |

| cfu per leaflet | 4.8 × 107 ± 0.6 | 4.7 × 106 ± 0.7 |

Calculations are derived from the leaves illustrated in Fig. 4 C and D of the amount of converted substrate. The averages ± SD of seven assays are shown. cfu, colony-forming units.

p35 Protein Was Not Detected in Transgenic Plants.

To verify that p35 protein expression was the cause of the observed phenotype, plants expressing high levels of p35 mRNA were tested for the presence of the p35 protein. Although the biological effects of the p35 transgene and the accumulation of p35 mRNA are unequivocal, neither Western analysis nor caspase inhibition assays were able to detect p35 protein in extracts of p35 tomato plants (data not shown). To demonstrate that active p35 protein could be made from our transgenic construct, we tested protein extracts of the A. tumefaciens strain that was used in the tomato p35 transformations. Taking advantage of the known leakiness of the CaMV promoter in Agrobacterium (33), we were able to show that both p35 protein and p35 activity are present in these Agrobacterium extracts, but not in control Agrobacterium extracts (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Discussion

The sphinganine analog mycotoxin, AAL-toxin, induces death in plant and animal cells with apoptotic morphology. AAL-toxin is a primary determinant of the Alternaria stem canker disease of tomato, in which toxin-dependent cell death precedes colonization by Aal. The ability to block cell death in plants by transgenic expression of antiapoptotic genes derived from an animal virus was examined for possible effects on plant diseases where programmed cell death could play an essential role in the infection process. The baculovirus p35 gene “is the only known gene that has antiapoptotic activity in all three of the major genetic systems used to study cell death, the nematode, the fly and the mouse, despite the fact that cellular homologs of p35 have not been discovered yet” (3). It inhibits key members of a class of cysteine proteases termed caspases that act as executioners of apoptosis and, as such, blocks apoptosis in insect cells during viral replication. The specificity of the p35 protein is resident in a tetrapeptide sequence, DQMD, that binds to the active site of the target caspase as an irreversible inhibitor.

Transgenic expression of p35 in tomato plants blocked AAL-toxin-induced death and provided protection against pathogen infection of leaves, stems, and fruit. Resistance to the AAL-toxin and Aal co-segregated with the expression of the p35 gene through the T3 generation. In addition, resistance to two other fungal pathogens (A. alternata and C. coccodes) and one bacterial pathogen (Pst) co-segregated with the p35 gene in the T3 progeny. The p35 gene also was stably transformed into tomato roots by A. rhizogenes that were up to 30 times more resistant to AAL-toxin than control roots. Conversely, transgenic expression of a binding site mutant of p35 (DQMD to DRIL) that was inactive against animal caspases-3 did not protect against AAL-toxin-induced root death. The exact mechanism by which p35 provides plant cells protection from death is not known. However, because the accepted role of p35 in animal cells is by inhibition of caspases (primarily caspase-3), we infer that the protection from pathogens by expression of the p35 gene in tomato is due to the inhibition of an, as yet, uncharacterized tomato caspase.

The existence of a caspase cascade in plants has been suggested by the ability of tetra-peptide caspase inhibitors, DEVD and YVAD, to block cell death associated with the hypersensitive response in tobacco (34) and completely block compatible necrotrophic pathogens (32). Recent reports have shown that the overexpression of the tomato Prf gene (35) or the Pto gene (36) result in increased pathogen resistance because of the induction of systemic acquired resistance (SAR), as indicated by induction of pathogen resistance (PR) gene expression. We found no evidence that the expression of p35 triggers systemic acquired resistance, as indicated by the lack of PR1 gene expression in the p35 transformed plants (data not shown; see Materials and Methods). In Arabidopsis, expression of PR1 is the most reliable molecular marker for SAR (37).

These results are consistent with the presence in plants of proteases with substrate-site specificity that is functionally equivalent to animal caspases. We are currently pursuing isolation of a tomato caspase protein by using functional assays. The biological conclusion is that diverse plant pathogens co-opt apoptosis during infection and that transgenic modification of pathways regulating programmed cell death in plants is a potential strategy for engineering broad-spectrum disease resistance in plants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Brad Hall and Kristina Zumstein for plant transformations. We thank Dr. Paul Friesen for the p35 gene and Promega for the generous gift of p35 antibodies. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement BIR-8920216 to the Center for Engineering Plants for Resistance Against Pathogens, a National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center. Expression of p35 in plants is protected under U.S. Patent 6,310,273.

Abbreviations

Aal, Alternaria alternata f. sp. lycopersici

AAL-toxin, sphinganine analog mycotoxin produced by Aal

Pst, bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato

References

- 1.Jacobson M. D., Weil, M. & Raff, M. C. (1997) Cell 88, 347-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joaquin A. M. & Gollapudi, S. (2001) J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 49, 1234-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clem R. J. (2001) Cell Death Differ. 8, 137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koyama A. H., Fukumori, T., Fujita, M., Irie, H. & Adachi, A. (2000) Microbes Infect. 2, 1111-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilchrist D. G. (1998) Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 36, 393-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danon A., Delorme, V., Mailhac, N. & Gallois, P. (2000) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 38, 647-655. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershberger P. A., Dickson, J. A. & Friesen, P. D. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 5525-5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clem R. J., Fechheimer, M. & Miller, L. K. (1991) Science 254, 1388-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunez G., Benedict, M. A., Hu, Y. & Inohara, N. (1998) Oncogene 17, 3237-3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villa P., Kaufmann, S. H. & Earnshaw, W. C. (1997) Trends Biochem. Sci. 22, 388-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Q., Krebs, J. F., Snipas, S. J., Price, A., Alnemri, E. S., Tomaselli, K. J. & Salvesen, G. S. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 10757-10765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bump N. J., Hackett, M., Hugunin, M., Seshagiri, S., Brady, K., Chen, P., Ferenz, C., Franklin, S., Ghayur, T., Li, P., et al. (1995) Science 269, 1885-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabizadeh S., Lacount, D. J., Friesen, P. D. & Bredesen, D. E. (1993) J. Neurochem. 61, 2318-2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson F. F. & Steller, H. (1998) Nature 391, 587-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue D. & Horvitz, H. R. (1995) Nature 377, 248-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugimoto A., Friesen, P. D. & Rothman, J. H. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 2023-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen G. (2000) Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 13, 649-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H., Li, J., Bostock, R. M. & Gilchrist, D. G. (1996) Plant Cell 8, 375-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryerson D. E. & Heath, M. C. (1996) Plant Cell 8, 393-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilchrist D. G. (1997) Cell Death Differ. 4, 689-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickman M. B., Park, Y. K., Oltersdorf, T., Li, W., Clemente, T. & French, R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6957-6962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilchrist D. & Grogan, R. G. (1976) Phytopathology 66, 165-173. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clouse S. D. & Gilchrist, D. G. (1987) Phytopathology 77, 80-82. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merrill A. H., Liotta, D. C. & Riley, R. T. (1996) Trends Cell Biol. 6, 218-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H., Jones, C., Ciacci-Zanella, J., Holt, T., Gilchrist, D. G. & Dickman, M. B. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 3461-3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tepfer D. (1984) Cell 37, 959-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertin J., Mendrysa, S. M., Lacount, D. J., Gaur, S., Krebs, J. F., Armstrong, R. C., Tomaselli, K. J. & Friesen, P. D. (1996) J. Virol. 70, 6251-6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vankan J. A. L., Joosten, M., Wagemakers, C. A. M., Vandenbergvelthuis, G. C. M. & Dewit, P. (1992) Plant Mol. Biol. 20, 513-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clouse S. D., Martensen, A. N. & Gilchrist, D. G. (1985) J. Chromatogr. 350, 255-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendrick J. B. J. & Walker, J. C. (1948) Phytopathology 38, 247-260. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher A. J., Cruz, W., Zoog, S. J., Schneider, C. L. & Friesen, P. D. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 2031-2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richael C., Lincoln, J. E., Bostock, R. M. & Gilchrist, D. G. (2001) Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 59, 213-221. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vancanneyt G., Schmidt, R., O'Connor-Sanchez, A., Willmitzer, L. & Rocha-Sosa, M. (1990) Mol. Gen. Genet. 220, 245-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.del Pozo O. & Lam, E. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 1129-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oldroyd G. E. D. & Staskawicz, B. J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10300-10305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang X., Xie, M., Kim, Y. J., Zhou, J., Klessig, D. F. & Martin, G. B. (1999) Plant Cell 11, 15-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maleck K., Neuenschwander, U., Cade, R. M., Deitrich, R. A., Dangl, J. L. & Ryals, J. A. (2002) Genetics 160, 1661-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.