Abstract

Enhancer DNA decoy oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) inhibit transcription by competing for transcription factors. A decoy ODN composed of the cAMP response element (CRE) inhibits CRE-directed gene transcription and tumor growth without affecting normal cell growth. Here, we use DNA microarrays to analyze the global effects of the CRE-decoy ODN in cancer cell lines and in tumors grown in nude mice. The CRE-decoy up-regulates the AP-2β transcription factor gene in tumors but not in the livers of host animals. The up-regulated expression of AP-2β is clustered with the up-regulation of other genes involved in development and cell differentiation. Concomitantly, another cluster of genes involved in cell proliferation and transformation is down-regulated. The observed alterations indicate that CRE-directed transcription favors tumor growth. The CRE-decoy ODN, therefore, may serve as a target-based genetic tool to treat cancer and other diseases in which CRE-directed transcription is abnormally used.

The cAMP response element (CRE) transcription factor complex is a pleiotropic activator that participates in the induction of a wide variety of cellular and viral genes (1). A synthetic, single-stranded, palindromic oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) composed of the CRE-enhancer sequence self-hybridizes to form a duplex/hairpin that competes with CRE enhancers for transcription-factor binding and inhibits CRE-directed gene transcription in vivo (2). The CRE-decoy inhibits cancer cell growth, both in vitro and in vivo (2), but does not harm normal cells.

The CRE-binding protein (CREB; ref. 3)/adenotranscription factor (4) family of transcription factors activates CRE-directed transcription in response to cAMP stimulation (3). CREB-transactivation activity depends on a coactivator, phospho-CREB-binding protein (CBP; ref. 5) and increases after phosphorylation by a cAMP-dependent protein kinase (3). CREB is also phosphorylated by other kinases, including calmodulin kinases II and IV (6) and the growth factor-inducible, ras-dependent RSK2 (7). CBP is also involved in the transcriptional activation of many other genes (8–10).

The CRE-decoy may regulate the expression of cAMP-responsive genes underlying tumorigenesis and tumor progression by modulating multiple sets of gene expression. We have used cDNA microarrays (11) to generate molecular portraits of growing tumors and of growth-arrested, regressing tumors, to identify CRE-decoy-induced molecular signatures not recognized by classical methods, and to define nonspecific side effects, if any, related to native ODN chemistry.

Experimental Procedures

ODNs.

We used the following phosphorothioate ODNs (2), CRE-decoy (5′-TGACGTCATGACGTCATGACGTCA-3′) and control ODN (5′-CTAGCTAGCTAGCTAGCTAGCTAG-3′) (2). Cells were treated with ODN as described (2). These ODNs were kindly provided by Sudhir Agrawal (Hybridon, Cambridge, MA).

Overexpression of CREB or KCREB in PC3M Cells.

CREB (pcDNA3-CREB) and KCREB (pcDNA3-KCREB) were kindly provided by Richard H. Goodman (Vollum Institute, Portland, OR). PC3M cells were transfected with CREB and KCREB genes as described (2).

Microarray Construction and Use.

A 15,000 human cDNA clone set of NIH IMAGE Consortium clones (http://image.llnl.gov; Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL) was sorted for genes relevant to signal transduction. A focused set of 1,152 genes were PCR-amplified and printed in duplicate at high density onto nylon membranes. 33P-labeled cDNAs prepared from total RNA isolated (RNeasy MidiKit, Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) from experimental and control samples were used to probe Signal Transduction arrays, washed, and exposed to phosphorimager screens for 1–3 days. IMAGEQUANT software (Molecular Dynamics) was used to convert the hybridization signals into raw intensity values, and the data were transferred into Microsoft EXCEL spreadsheets predesigned to associate the IMAGEQUANT data format to the correct gene identities.

Data Processing.

Raw-intensity data for each experiment was normalized by z-transformation, as described (12).

Cluster.

Software programs developed at Stanford University (M. Eisen; www.microarrays.org/software; ref. 13) were used to determine hierarchical clustering of experimental variation in gene expression. The cluster algorithm was set to complete linkage clustering by using the uncentered Pearson correlation; see the Cluster manual at www.microarrays.org/software for computational details. All data sets and image files used to generate Figs. 1–3 are included in the supplementary information at www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/rrb/dna/dnapubs.htm.

Results

Analysis of Gene Expression in Tumors Exposed to the CRE-Decoy ODN.

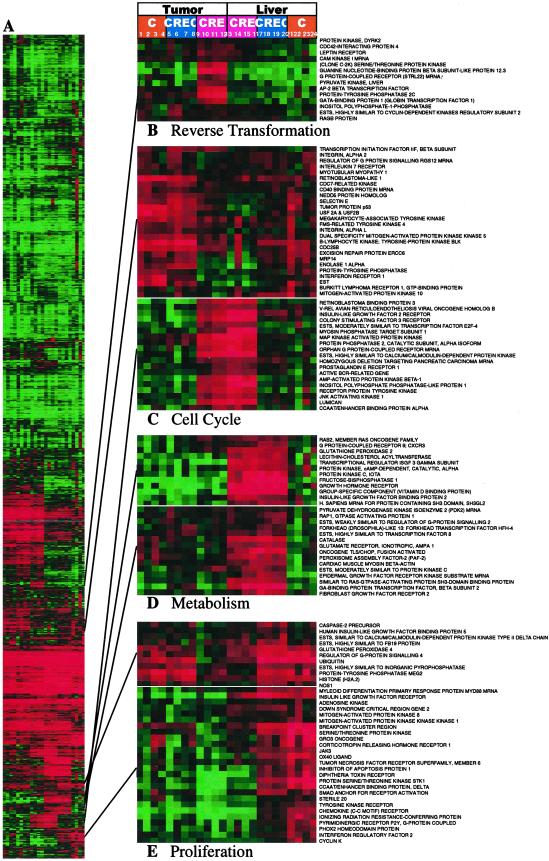

Fig. 1 presents the alterations in the gene expression profile induced by the CRE-decoy in PC3M tumors and in host animal livers. We used a hierarchical clustering algorithm (13) to group genes on the basis of similarity in the pattern with which their expression varied over all samples. We show the data in a matrix format and the expression level of each gene in color (13). Distinct samples representing similar gene patterns from untreated control tumors and control ODN-treated tumors were clustered in immediately adjacent columns. Likewise, samples from CRE-decoy-treated tumors and host livers were clustered in adjacent columns. We also clustered samples from two independent experiments in adjacent columns, leading to quadruplicate analysis for each cDNA element in this map.

Fig 1.

Reverted phenotype of PC3M tumors treated with the CRE-decoy. PC3M human prostate carcinoma cells (2.0 × 106) were inoculated s.c. into the left flank of nude mice. When tumors became palpable, the CRE-decoy or control ODN (0.1 mg/0.1 ml of saline per mouse, daily) or saline (0.1 ml per mouse) was injected i.p. into the mice. Tumor volumes were obtained from daily measurement and calculation (26). At the end of the experiment, animals were killed, and tumors, livers, and spleens were removed, weighed, immediately frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C until used. Lanes: 1–4, untreated control tumors; 5–8, control ODN-treated tumors; 9–12, CRE-decoy-treated tumors; 13–16, CRE-decoy-treated livers; 17–20, control ODN-treated livers; and 21–24, untreated control livers. The entire cluster image is shown in A. Full gene names are shown for representative clusters containing functionally related genes involved in reverse transformation (B), cell cycle (C), metabolism (D), and proliferation (E). These clusters also contain uncharacterized genes and named genes not involved in these processes. The size of the tumors compared with untreated (saline-injected) control tumors were 50% and 95% of their original size after 4 days of treatment with CRE-decoy and control ODN, respectively. There was no sign of systemic toxicity in treated animals, and the sizes of the liver and spleen remained unchanged.

Untreated or control ODN-treated tumors and tumors treated with CRE-decoy exhibited coordinated expression (Fig. 1A). However, expression patterns differed between controls and CRE-decoy treatment. The expression levels were altered for ≈10% of the genes on the array were altered (≥2-fold up-regulated or down-regulated) in CRE-decoy-treated tumors and in host animal livers (see supplementary information). In contrast, tumors treated with the control ODN exhibited a minimal alteration in the expression profile, which did not mimic that caused by the CRE-decoy (see supplementary information). On the basis of global similarities in gene expression patterns, the algorithm showed differences, with few exceptions, between CRE-decoy-treated and untreated or control ODN-treated tumors and livers. We defined clusters of coordinately expressed genes as “signatures” (14, 15) by the biological process in which its component genes were known to function (Fig. 1 B–E). These signatures clearly distinguished untreated, growing tumors from tumors undergoing growth arrest and regressing upon decoy treatment.

Molecular Signatures of Tumor Regression.

Genes that define cell cycle signatures were either markedly up-regulated or down-regulated in decoy-treated tumors (Fig. 1C). Most affected of these expression signatures were genes that control cell cycle at the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint, including genes encoding CDC25B (M-phase-inducer phosphatase 2), an excision repair protein, the tumor protein p53, and CDC7-related kinase, which were markedly down-regulated in decoy-treated tumors. On the other hand, genes that regulate the cell cycle at the G1/S transition, including genes for retinoblastoma-binding protein 3, ESTs, and the CSF3 receptor, were highly up-regulated in decoy-treated tumors. These alterations were specific to the decoy. In both tumors and livers, the CRE-decoy, but not the control ODN, suppressed genes that define the “cell proliferation signature” (Fig. 1E), which included genes for diverse protein kinases and phosphatases, growth factors, growth factor receptors, and cyclin K. Thus, the altered expression of the cell cycle signature and proliferation signature can clearly distinguish the growth-arrested and regressing tumors treated with CRE-decoy from the untreated growing tumors or tumors treated with control ODN.

Tumor-Specific Expression Signature and Reverse Transformation.

The most striking distinction between CRE-decoy-treated tumors and control tumors was demonstrated by the “reverse transformation” signature, which was highly up-regulated in a manner specific to tumors and to CRE-decoy treatment (Fig. 1B). This signature was expressed at low levels in untreated, growing tumors or in tumors treated with control ODN, as well as in nontransformed normal livers of host animals that were untreated or treated with the decoy ODN. The reverse transformation signature included a cluster of genes that are involved in the regulation of development, cell growth, and differentiation (16–19). Thus, the up-regulation of genes in this signature provide the molecular signature characteristic of CRE-decoy-induced tumor regression. This result has also been observed for an antisense ODN targeted against the RIα regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA; ref. 15).

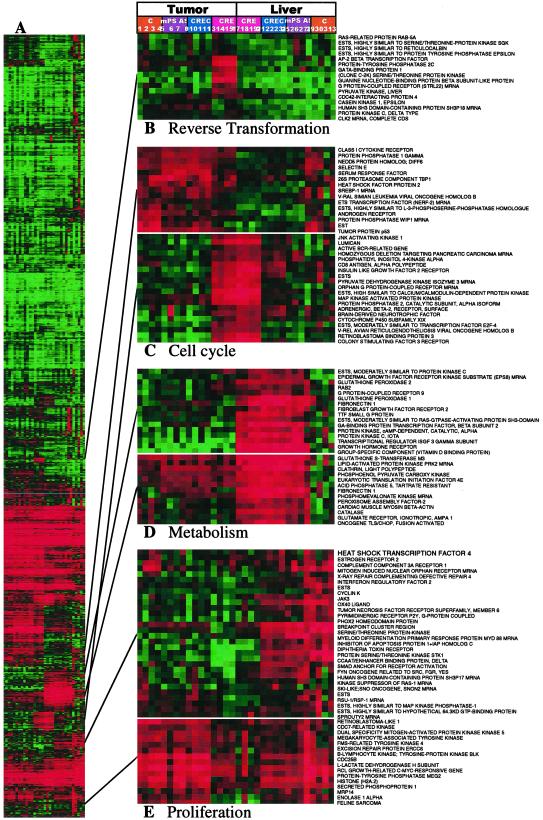

These molecular effects were consistent with the growth inhibition and the reverted phenotype observed in transformed cells treated with these ODNs (20–24). Importantly, the cluster analysis observed in the absence (Fig. 1 B, C, and E) and presence (Fig. 2 B, C, and E) of the samples treated with RIα antisense PS-ODN (mPSAS) almost completely mirrored each other with respect to CRE-decoy-induced alterations in the expression signatures. This result supports the remarkable specificity of the CRE-decoy effect on gene expression patterns in the cell, especially in tumor cells. Thus, genomic-scale analysis confirmed and extended previous findings based on classical biochemical and cell biology methods.

Fig 2.

CRE-decoy inhibition is unrelated to PS-ODN or CpG side effects. Data are the same as in Fig. 1, except that data from mouse RIα antisense PS-ODN (mPSAS)-treated tumors and livers were included in the cluster analysis. Lanes: 1–4, untreated control tumors; 5–8, mPSAS-treated tumors; 9–12, control ODN-treated tumors; 13–16, CRE-decoy-treated tumors; 17–20, CRE-decoy-treated livers; 21–24, control ODN-treated livers; 25–28, mPSAS-treated livers; and 29–32, untreated control livers.

Liver-Specific Expression Patterns and Side Effects.

We addressed whether the CRE-decoy promoted the nonspecific side effects associated with other PS-ODNs (25). Cluster analysis was performed on the samples described in Fig. 1, along with samples treated with an antisense PS-ODN targeted against codons 8–13 of the mouse protein kinase A RIα (mPSAS). This ODN can hybridize with both human and mouse RIα mRNAs (15, 26). Genes encoding metabolic enzymes such as glutathione peroxidases, catalase, glutamate receptor, and GST were markedly up-regulated in livers, but not in tumors, after treatment with all PS-ODNs tested (Fig. 2D). The up-regulation of cellular metabolism genes observed in liver with CRE-decoy treatment thus may reflect nonsequence-specific side effects of PS-ODNs in general.

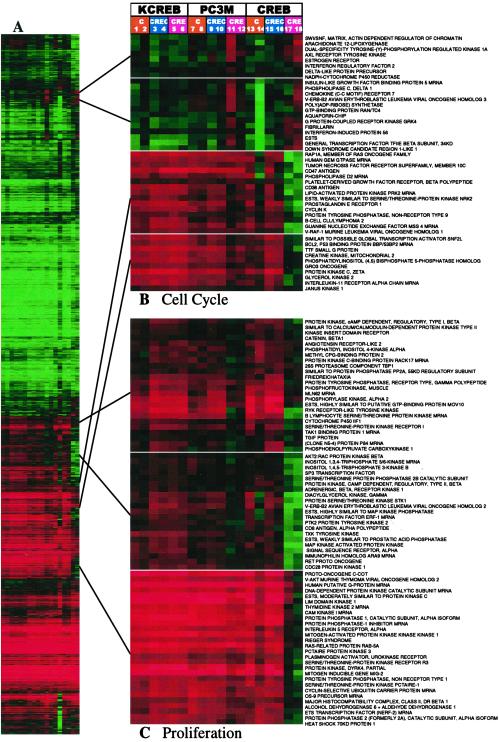

Mutant KCREB Overexpression and CRE-Decoy Resistance.

The CRE-decoy-induced alterations in gene expression pattern shown above (Figs. 1 and 2) could result from actions other than the blockade of CRE-directed transcription. To determine whether these alterations resulted from interactions between the CRE-decoy and the DNA-binding domain of the transcription factor, we studied the effects of CRE-decoy in cells overexpressing the KCREB mutant. KCREB contains a mutation of a single amino acid in the DNA-binding domain and is, therefore, incapable of binding native CRE sequences (27). In cells overexpressing wild-type CREB, CRE-decoy treatment altered expression of the cell cycle and proliferation signatures in a pattern similar to that observed in parental cells. However, cells overexpressing KCREB failed to show any alterations in these expression signatures after decoy treatment (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with the ability of the CRE-decoy to compete with the CRE-enhancer for transcription-factor binding, resulting in the suppression of CRE- and AP-1-directed transcription in the cell (2).

Fig 3.

Cells overexpressing KCREB fail to exhibit the CRE-decoy expression signatures. Data from untreated control cells, control ODN-treated, CRE-decoy-treated cells of untransfected PC3M parental cells, and wild-type CREB or mutant KCREB-transfected cells (see Experimental Procedures) were combined and clustered. Lanes: 1 and 2, untreated; 3 and 4; control ODN-treated; 5 and 6, CRE-decoy-treated KCREB-overexpressing cells; 7 and 8, untreated; 9 and 10, control ODN-treated; 11 and 12; CRE-decoy-treated parental PC3M cells; 13 and 14, untreated; 15 and 16, control ODN-treated; 17 and 18, CRE-decoy-treated CREB-overexpressing cells. (A) Entire cluster image. (B) Cell-cycle signature. (C) Proliferation signature. These clusters also contain unknown genes and named genes not involved in defined functions.

CRE-Decoy Expression Signatures in Various Cancer Cells.

Although the CRE-decoy triggered similar alterations in expression pattern in various cancer cell lines, the response of each cell line differed (see supplementary information at www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/rrb/dna/dnapubs.htm). The hormone-independent MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells exhibited the greatest response to decoy treatment, and the multidrug-resistant HCT-15 colon carcinoma cells exhibited the smallest response. A comparison of these decoy-induced expression signatures with those depicted in Fig. 3 shows a remarkable overlap in the cluster pattern and in individual gene expression patterns among these cell lines. The affected genes clustered into cell cycle and proliferation signatures, and all were coordinately down-regulated upon decoy treatment (Fig. 3 and supplementary information).

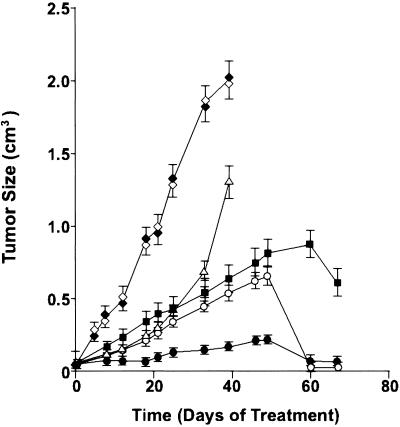

CRE-Decoy Inhibition of Tumor Growth.

We examined the effect of the CRE-decoy on the in vivo growth of hormone-dependent breast tumors by using s.c.-implanted MCF-7 cells in nude mice. The CRE-decoy time-release pellet markedly inhibited tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner up to day 50, and by day 60 tumor growth was almost completely suppressed even at a lower dose (2.5 mg/kg/day pellet; Fig. 4). Tamoxifen, an antiestrogen (60-day release pellet) used as a positive control for growth inhibition, exhibited much lower efficacy than did the CRE-decoy pellet. Compared with the time-release pellet, decoy treatment given by daily i.p. injection was not as effective in growth inhibition. By comparison, untreated control tumors (placebo) and tumors treated with the control ODN (CREC) exhibited continued growth, with death at day 40.

Fig 4.

Inhibition of MCF-7 tumor growth in nude mice by CRE-decoy ODN in a time-release pellet. Tumor cells (1–2 × 106 per mouse) were inoculated into mammary gland fat pad of athymic mice. For estrogen-dependent tumor growth, a 17β–estradiol pellet (90-day release) was implanted s.c. 1 day before cell inoculation. Drug administration was started 14–21 days after cell inoculation, when tumors became palpable. Time-release (60-day) pellets containing 2.5 mg of CRE (○, CRE-decoy), 5.0 mg of CRE-decoy (•), or 5.0 mg of CRE (⋄, control ODN) at 1 kg/day were implanted interscapularly. CRE was also injected i.p. at 5.0 mg/kg daily, 5 times per week, for 8 weeks (▵). A tamoxifen pellet (▪, 60-day release, 4.2 mg/kg/day) was implanted interscapularly. A placebo (♦, vehicle pellet) was implanted interscapularly. Tumor volumes were obtained from daily measurements and calculations (26). Data represent means ± SD of five to seven tumors in each group.

Discussion

This study shows that a genomic view of gene expression and gene modulation in cancer can identify new molecular signatures of cAMP signaling that may be critically involved in cancer genesis and progression. CRE-decoy inhibition of cAMP signaling generates a molecular portrait of growth-arrested, regressing tumors, which is clearly distinct from that of growing, untreated tumors in which CRE-directed transcription is not blocked. Expression signatures induced by the CRE-decoy have not previously been identified by classical biochemical or molecular biology methods. In addition, array analysis defined nonspecific side effects in gene expression that are unrelated to the CRE-decoy effect but are related to the phosphorothioate chemistry of ODN in general. This analysis also showed that the immune response was not stimulated by the CRE-decoy (Figs. 1 C and E and 2E).

The molecular portrait of the growth-arrested, regressing tumors, which is highlighted in this study, includes the reverse transformation signature that was greatly up-regulated in tumors in a tumor-decoy-specific manner. This signature includes the gene for the AP-2β transcription factor, which binds to the AP-2 enhancer and activates or suppresses genes involved in a large spectrum of important biological functions (18). AP-2β functions similarly to a tumor suppressor in breast cancer (28), as well as to a suppressor for a number of genes including c-myc, c/EBP-α, and MCAM/MUC18 (19). In addition, the AP-2 factor, as an interactive partner of the YY1 transcription factor, is involved in the regulation of the cell cycle, cell growth, and differentiation (29). Importantly, the induction of the AP-2β factor by the CRE-decoy may reflect a feedback control of the cell's signal, which compensates for the loss of cAMP signaling resulting from the decoy blockade of CRE-directed transcription.

The CRE responds efficiently to the cAMP-inducing agent forskolin but not to TPA, whereas AP-2 is unique in its ability to respond to two, distinct second messengers, TPA and cAMP. Thus, in our study, tumor cells, in response to the blockade of CRE-transcription, assume an alternate pathway for cAMP signaling. The up-regulation of the AP-2β factor gene by the CRE-decoy specifically in tumors, but not in the livers of the host animals, suggests that CRE-directed transcription stimulates growth in tumor cells, but not in normal cells. This finding provides molecular support for the previous observation (2) that the CRE-decoy inhibits tumor cell growth without affecting normal cell growth.

The genomic view of gene expression confirmed and extended the previous findings (2, 30, 31) that the CRE-decoy works by blocking the ability of transcription factors to bind to the CRE-enhancer. This study presents a clear correlation between decoy-inducible expression signatures and the presence of wild-type CREB in the cell. Such expression signatures are not inducible in cells overexpressing mutant KCREB; these cells have lost the CRE-binding function. Therefore, the growth inhibitory effect of the decoy may result, at least in part, from interference of the transcription factor binding to the cis-element.

Gene expression profiling further shows that the CRE-decoy-induced inhibition of tumor growth is unrelated to immune stimulation, despite the fact that the decoy contains the CpG motif known to be optimal for immune stimulation in mice (32). This may have occurred because of the rapid accumulation of the decoy ODN in the nucleus and its complex formation with transcription factors and the CRE-decoy blockade of AP-1 transcription (2). Both the AP-1 and NFκB pathway are required for CpG immune stimulation (33).

Finally, the genomic-scale view of gene expression modulation in cancer cells provides a unique perspective on the development of new cancer therapeutics based on a molecular understanding of the cancer phenotype. Our study shows that blocking cAMP signaling by using the CRE-decoy results in reverse transformation, a new molecular phenotype in which tumors are arrested in growth and regressing. The growing tumor phenotype expresses and transcribes modules, composed of hundreds of genes, differently from the regressing tumor phenotype. This difference may explain the malignant behavior of the tumor. CREB, the CRE-transcription factor, must bind CBP to be transactivated. CBP also serves as the coactivator for numerous other transcription factors (8, 9). Thus, the CRE-decoy, working upstream of the transcription machinery, may prove to be a gene-targeted tool for treating cancer, and it may define other upstream signal-transduction molecules whose constitutive expression leads to the expression of malignant transcription programs.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Agrawal for ODNs and R. Goodman for plasmids pcDNA3-CREB and pcDNA3-KCREB. We also thank Ms. Christine Hamel and Dr. Frances McFarland, both of Palladian Partners, Inc., who provided editorial support under Contract N02-BC-76212/C2700212 with the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

CRE, cAMP response element

ODN, oligodeoxynucleotide

CREB, CRE-binding protein

References

- 1.Roesler W. J., Vandenbark, G. R. & Hanson, R. W. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263 9063-9066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park Y. G., Nesterova, M., Agrawal, S. & Cho-Chung, Y. S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 1573-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montminy M. R. & Bilezikjian, L. M. (1987) Nature 328 175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hai T. W., Liu, F., Allegretto, E. A., Karin, M. & Green, M. R. (1988) Genes Dev. 2 1216-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chrivia J. C., Kwok, R. P., Lamb, N., Hagiwara, M., Montminy, M. R. & Goodman, R. H. (1993) Nature 365 855-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheng M., Thompson, M. A. & Greenberg, M. E. (1991) Science 252 1427-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xing J., Ginty, D. D. & Greenberg, M. E. (1996) Science 273 959-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arias J., Alberts, A. S., Brindle, P., Claret, F. X., Smeal, T., Karin, M., Feramisco, J. & Montminy, M. (1994) Nature 370 226-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman R. H. & Smolik, S. (2000) Genes Dev. 14 1553-1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agadir A., Shealy, Y. F., Hill, D. L. & Zhang, X. (1997) Cancer Res. 57 3444-3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schena M., Shalon, D., Davis, R. W. & Brown, P. O. (1995) Science 270 467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vawter M. P., Barrett, T., Cheadle, C., Sokolov, B. P., Wood, W. H., III, Donovan, D. M., Webster, M., Freed, W. J. & Becker, K. G. (2001) Brain Res. Bull. 55 641-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisen M. B., Spellman, P. T., Brown, P. O. & Botstein, D. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 14863-14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alizadeh A. A., Eisen, M. B., Davis, R. E., Ma, C., Lossos, I. S., Rosenwald, A., Boldrick, J. C., Sabet, H., Tran, T., Yu, X., et al. (2000) Nature 403 503-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho Y. S., Kim, M.-K., Cheadle, C., Neary, C., Becker, K. G. & Cho-Chung, Y. S. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 9819-9823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser M., Imhof, A., Pscherer, A., Bauer, R., Amselgruber, W., Sinowatz, F., Hofstadter, F., Schule, R. & Buettner, R. (1995) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 121 2779-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart H. J., Brennan, A., Rahman, M., Zoidl, G., Mitchell, P. J., Jessen, K. R. & Mirsky, R. (2001) Eur. J. Neurosci. 14 363-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilger-Eversheim K., Moser, M., Schorle, H. & Buettner, R. (2000) Gene 260 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaubatz S., Imhof, A., Dosch, R., Werner, O., Mitchell, P., Buettner, R. & Eilers, M. (1995) EMBO J. 14 1508-1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alper O., Bergmann-Leitner, E. S., Abrams, S. & Cho-Chung, Y. S. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 218 55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho Y. S., Kim, M.-K., Tan, L., Srivastava, R., Agrawal, S. & Cho-Chung, Y. S. (2002) Clin. Cancer Res. 8 607-614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava R. K., Srivastava, A. R., Park, Y. G., Agrawal, S. & Cho-Chung, Y. S. (1998) Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 49 97-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srivastava R. K., Srivastava, A. R., Seth, P., Agrawal, S. & Cho-Chung, Y. S. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 195 25-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noda M., Ko, M., Ogura, A., Liu, D. G., Amano, T., Takano, T. & Ikawa, Y. (1985) Nature 318 73-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agrawal S. & Zhao, Q. (1998) Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 8 135-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nesterova M. & Cho-Chung, Y. S. (1995) Nat. Med. 1 528-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walton K. M., Rehfuss, R. P., Chrivia, J. C., Lochner, J. E. & Goodman, R. H. (1992) Mol. Endocrinol. 6 647-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gee J. M., Robertson, J. F., Ellis, I. O., Nicholson, R. I. & Hurst, H. C. (1999) J. Pathol. 189 514-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu F. & Lee, A. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 28-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park Y. G., Park, S., Lim, S. O., Lee, M. S., Ryu, C. K., Kim, I. & Cho-Chung, Y. S. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281 1213-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho-Chung Y. S., Park, Y. G., Nesterova, M., Lee, Y. N. & Cho, Y. S. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 212 29-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krieg A. M., Yi, A. K., Matson, S., Waldschmidt, T. J., Bishop, G. A., Teasdale, R., Koretzky, G. A. & Klinman, D. M. (1995) Nature 374 546-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aderem A. & Hume, D. A. (2000) Cell 103 993-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]