Abstract

A sensitive plant infection model was developed to identify virulence factors in nontypeable, alginate overproducing (mucoid) Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Nontypeable strains with defects in lipopolysaccharide O-side chains are common to CF and often exhibit low virulence in animal models of infection. However, 1,000 such bacteria were enough to show disease symptoms in the alfalfa infection. A typical mucoid CF isolate, FRD1, and its isogenic mutants were tested for alfalfa seedling infection. Although defects in the global regulators Vfr, RpoS, PvdS, or LasR had no discernable effect on virulence, a defect in RhlR reduced the infection frequency by >50%. A defect in alginate biosynthesis resulted in plant disease with >3-fold more bacteria per plant, suggesting that alginate overproduction attenuated bacterial growth in planta. FRD1 derivatives lacking AlgT, a sigma factor required for alginate production, were reduced >50% in the frequency of infection. Thus, AlgT apparently regulates factors in FRD1, besides alginate, important for pathogenesis. In contrast, in a non-CF strain, PAO1, an algT mutation did not affect its virulence on alfalfa. Conversely, PAO1 virulence was reduced in a mucA mutant that overproduced alginate. These observations suggested that mucoid conversion in CF may be driven by a selection for organisms with attenuated virulence or growth in the lung, which promotes a chronic infection. These studies also demonstrated that the wounded alfalfa seedling infection model is a useful tool to identify factors contributing to the persistence of P. aeruginosa in CF.

Individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF) are highly susceptible to bronchiopulmonary infection with the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The lungs of CF patients are typically colonized by unusual P. aeruginosa strains that have a highly mucoid colony morphology due to the overproduction of a viscous expolysaccharide called alginate (1). The appearance of mucoid P. aeruginosa in the CF lung correlates with the establishment of a chronic lung infection and generally a poor prognosis for the patient (1). An important advance in the study of P. aeruginosa pathogenesis and pulmonary pathology was the development of a chronic infection model induced in the lungs of rats by means of transtracheal instillation of agar beads containing 104 viable bacteria (2). This model has been used with serotyped P. aeruginosa isolates of CF origin, and isogenic mucoid and nonmucoid strains have shown similar pathologies with numerous foci of necrosis, inflammation, and similar times of persistence in the lung (2, 3).

Defective lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is another important property of many P. aeruginosa strains associated with CF. Among 26 CF isolates tested, only six had typeable LPS O side chains (4). Others have also reported that the majority of strains of P. aeruginosa isolated from CF patients with chronic infection have lost O serotype reaction and display sensitivity to normal human serum, which is typical of rough strains (5). In another study of 20 CF strains, 13 showed a rough phenotype, and these isolates displayed no or low virulence in a burned mouse model of P. aeruginosa infection (6). This study supports the report of Cryz et al. (7) that LPS is an important virulence factor in acute and systemic infections. In contrast, pulmonary infections of CF patients tend to remain localized. CF strains can differ from non-CF isolates in other ways including reduced protease production (6, 8), reduced exoenzymes (9), and also alterations in exotoxin A (10, 11), the type III secretion apparatus (12), and motility (13, 14). Thus, there seems to be a progressive host selection in the lungs of patients with CF against certain bacterial properties normally associated with bacterial virulence (6). Some CF isolates display hypermutability (15) or have chromosomal rearrangements due to insertion of plasmids or pathogenicity islands (16–18).

The alterations and attenuations observed in multiple virulence factors suggest that many CF strains of P. aeruginosa have adapted to use an alternate set of pathogenic mechanisms that promote chronic lung disease in the CF patient. Unfortunately, the LPS-defective (untypeable) strains that are so common to chronic CF infections show low virulence in the established animal models. Recently, alternative models of infection have been developed to identify new virulence determinants of P. aeruginosa. Such alternative systems have been based on plants (19), insects (20), and nematodes (21). These are often faster, more convenient, and less expensive than animal infection systems. Virulence genes identified by alternative approaches have also been shown to play a role in an animal model (22, 23). Thus, alternate host systems can be used to streamline the discovery of new virulence determinants. To advance our understanding of the mechanisms of pathogenesis in P. aeruginosa isolated from CF patients, we developed an infection model using wounded alfalfa seedlings, which proved to be a highly sensitive assay for the pathogenesis of attenuated P. aeruginosa strains. The system is rapid, inexpensive, and adaptable for use with a variety of P. aeruginosa strains. Here, we demonstrate its usefulness for identifying virulence determinants in the often studied mucoid and LPS-defective CF isolate, P. aeruginosa strain FRD1 (24).

Methods

Assay of Alfalfa Infection by P. aeruginosa.

Seeds of alfalfa variety 57Q77, a WT strain not bred for pest resistance, were kindly provided by Pioneer Hi-Bred International Inc. (Wichita, KS). Alfalfa seeds, prepared as described (25), were disinfected and germinated by soaking in concentrated sulfuric acid (≈300 seeds in 10 ml) for 20 min followed by four washes with 500 ml of sterile distilled water (dH2O) per wash. The seeds were placed in a 125-ml flask with 60 ml of dH2O, incubated at 30°C with shaking for 7 h, rinsed twice with 60 ml dH2O, covered with 60 ml dH2O, and incubated overnight at 30°C with shaking. The seedlings germinated overnight and were then distributed onto water agar plates (dH20 water solidified with 1% Difco Bacto agar and 1% Difco Noble agar) at 10 seedlings/plate. Meanwhile, strains of P. aeruginosa were cultured at 30°C in L broth (10% bacto tryptone/5% yeast extract/5% NaCl) with aeration to an OD600 of 2.0, which represented ≈1 × 109 cells per ml. These bacterial cultures were serially diluted in saline, and samples were plated onto L agar plates to determine colony-forming units (cfu). Alfalfa seedlings were wounded at leaf surface by the simple insertion of a 20-gauge needle. Wounded seedlings were immediately inoculated with 10 μl of bacterial cell suspensions. Water agar plates containing inoculated seedlings were sealed with parafilm and placed on a bench top where each plate received equivalent amounts of indirect daylight. Disease symptoms appeared at about day 6. Some infected alfalfa seedlings were homogenized in 1 ml of saline with a tissue grinder (Kontes, size C), and the suspension was serially diluted in saline and plated to determine bacterial cell counts. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM and analyzed for significance by using an ANOVA (InStat GraphPad Software, San Diego). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Construction of P. aeruginosa Mutants to Test in the Alfalfa Seedling Model.

WT strains examined in this study were FRD1, a mucoid, LPS-defective (serum-sensitive) CF sputum isolate (24), and PAO1, a nonmucoid wound isolate (26, 27) that is virulent in animal models. Other CF isolates tested were obtained from various hospital sputum samples of different CF patients, and two of these (DO133 and DO326) were mucoid and two (DO60 and DO139) were nonmucoid. Environmental strains ENV2 and ENV8 had been isolated from vegetable material, and ENV10 and ENV46 were river isolates (28).

In the FRD1 mucoid strain background, an algD:Tn501 mutant defective for alginate production was used (29), and an rpoS101:aacCI mutant was used (30). A dsbA mutant, FRD-LS211, was constructed with plasmid pLS204 as described (31). A pvdS mutant, FRD-SS161, was generated by using pBXBR (32), into which the nonpolar aacCI gene cartridge (conferring resistance to gentamycin at 200 μg/ml) from pUCGM1 (33) was inserted in the StuI site within pvdS. An origin of transfer (oriT) on a 1.2-kb EcoRI fragment from pSF1 (34) was inserted into vector sequences to form pSS84, which was conjugated into FRD1 for allelic exchange. Potential pvdS mutants were isolated as gentamicin-resistant (Gmr)/carbenicillin-sensitive (Cbs) colonies and verified by PCR analysis. To generate the lasR501:aacCIΩ mutant, FRD-SS905, a 1.35-kb PCR fragment of lasR in pUC19 was digested with NaeI, the aaccIΩ(Gmr) cassette was inserted into lasR, and then the 1.3-kb EcoRI oriT fragment was inserted in vector sequences to form pSS83 for allelic exchange with the FRD1 chromosome. To generate the rhlR201:aacCI mutant, FRD-SS1206, a 1.3-kb PCR fragment of rhlR in pUC19 was digested with BamHI, and the Gmr cassette was inserted in rhlR. The rhlR201:aacCI null allele was cloned into the SmaI site of pEX100-T (35) to generate pSS70, which was used for allelic exchange in FRD1. To generate the vfr401:aacCIΩ mutant, FRD-SS316, a 1.3-kb PCR fragment of vfr in pUC19 was cut with BclI, the Gmr cassette was inserted in vfr, and then the 1.3-kb EcoRI oriT fragment was inserted in vector sequences to form pSS63 for allelic exchange with the FRD1 chromosome. To generate algT mutants, the algT gene in pUCP18 (a gift from M. Franklin, Montana State University, Bozeman) was digested at the SacII site, and the aacCI cartridge was inserted in either orientation. EcoRI fragments containing algT:aacCI alleles were ligated into vector pLS201 (pBK+ with oriT) to obtain pLS584 and pLS585, with aacCI in the opposite (pLS584) and transcribing (pLS585) orientations of algT, respectively. These were used for allellic exchange in FRD1 to construct algT:aacCI mutants DO-LS586 and DO-LS588, with the aaaCI gene inserted in the opposite (polar) and same (nonpolar) orientations, respectively.

In the PAO1 background, the mucA22 mutant PDO300 was used, which produces alginate (36). Plasmids pLS584 and pLS585 were used to construct algT:aacCI mutants PDO-LS591 and PDO-LS592, with the aaaCI gene inserted in the opposite (polar) and same (nonpolar) orientations, respectively.

Alginate Assays.

Infected alfalfa seedlings were removed from water agar plates, which were then flooded and scraped with 2 ml of saline (0.85% NaCl). The suspension was centrifuged to remove bacteria. Supernatant samples were dialyzed against dH2O, prepared as described (30), and alginate (i.e., uronic acid) was measured by the carbazole method (37) with Macrocystis pyrifera alginate (Sigma) as a standard.

Animal Studies.

The ability of strain FRD1 to cause chronic respiratory infections was examined in the agar bead model in rats as described by Cash et al. (2). Fifteen male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 200–220 g (Charles River Breeding Laboratories) were tracheostomized under anesthesia and inoculated with ≈104 cfu FRD1 embedded in agar beads as described (2). On days 7 and 14 postinfection, the lungs from five animals in each group were removed aseptically and homogenized (Polytron homogenizer, Brinkmann) in 3 ml of PBS (0.05 M, pH 7.2, containing 0.9% saline, PBS). Serial dilutions were plated on trypticase soy agar. On day 14 postinfection, the lungs of five animals were removed en bloc, fixed in 10% formalin, and examined for qualitative and quantitative pathological changes as described (38, 39).

Results

P. aeruginosa Isolates Infect Alfalfa Seedlings.

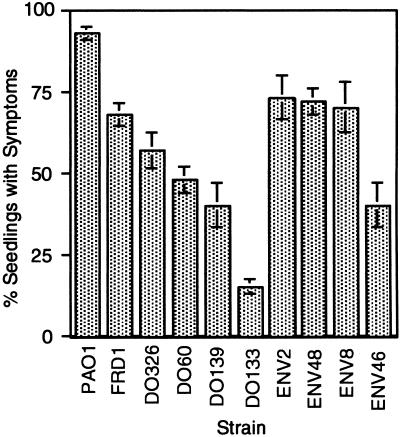

A simple model of P. aeruginosa opportunistic infectious disease was developed in which alfalfa seeds were germinated overnight, wounded with a needle, and then inoculated with dilute suspensions of P. aeruginosa. Infected seedlings showed disease symptoms that could readily be scored in 6 days. We tested a variety of P. aeruginosa isolates for virulence in this plant model. This included strain PAO1, a wound isolate that is known to be virulent in many animal models of infection, and a mucoid and nontypeable CF isolate, strain FRD1. In addition, other WT strains were tested for virulence, including four additional CF isolates and four environmental strains. All of these WT P. aeruginosa strains produced disease symptoms when wounded alfalfa seedlings were inoculated with only 1,000 bacteria. PAO1 was the most virulent strain tested, causing disease symptoms in ≈95% of infected seedlings with this infectious dose (Fig. 1). Among the CF isolates, FRD1 was the most virulent strain tested with ≈70% of the infected seedlings producing disease symptoms (Fig. 1). Three of the four other CF isolates produced disease symptoms in ≈50% of the plants. Three of four environmental isolates caused symptoms in ≈75% of the seedlings (Fig. 1). All of the environmental strains tested were serum-resistant, whereas all of the CF isolates used were serum-sensitive (i.e., lack O-side chains of LPS), suggesting that LPS may contribute to the plant pathogenesis.

Fig 1.

Frequency of infection of alfalfa seedlings with P. aeruginosa strains. For each strain of P. aeruginosa, 60 wounded seedlings were inoculated with ≈103 bacteria. Values show the average fraction (percentage ± SE) of the seedlings showing disease symptoms as a measure of virulence. Strains tested were wound isolate PAO1, five CF isolates (FRD1, DO326, DO60, DO139, DO133), and four environmental isolates (ENV2, ENV48, ENV8, ENV46). Data are the average of three experiments.

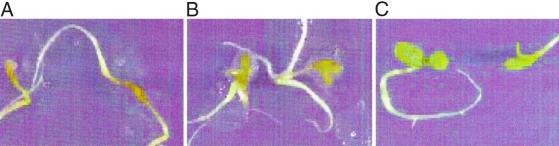

The morphology of the P. aeruginosa-induced plant disease showed a variety of symptoms, including chlorosis, water-soaked lesions, and complete maceration of tissue (Fig. 2A). The disease phenotype with CF strains like FRD1 was similar to that of PAO1 except that the former displayed the obvious production of capsular polysaccharide in the plant wound (Fig. 2B), which tested positive for alginate (data not shown). The simplicity of this P. aeruginosa infection model suggested that it had potential as a tool to evaluate putative virulence factors by analysis of specific mutants.

Fig 2.

Infection of alfalfa seedlings. Photographs of wounded alfalfa seedlings after infection with ≈1,000 bacteria and incubation for 7 days. (A) Infection by wound isolate PAO1 shows necrosis and tissue masceration. (B) Infection by mucoid CF isolate, FRD1, is less severe and shows accumulation of alginate in the plant wound. (C) Saline-inoculated negative control.

Strain FRD1 Infection of the Rat Lung.

In the rat agar bead chronic infection model (2), the typeable strain PAO1 has been reported to persist for at least 9 months (40). To compare the virulence of a nontypeable CF isolate in both the plant and a relevant animal model system, we examined the ability of FRD1 to establish a chronic infection by using the rat agar bead infection model (2). Rats were infected with 104 cfu FRD1. On day 7 postinfection, 1.9 × 104 ± 1.2 × 104 cfu (mean ± SE) were recovered from lung homogenates, but on day 14 postinfection, only 4.1 × 101 cfu were recovered from the lung. Thus, FRD1 was not able to establish a long-term chronic infection in this animal model. Thus, an alternative infection model was especially needed to be able to assess potential virulence genes in attenuated CF isolates of P. aeruginosa like FRD1.

Comparison of PAO1 and FRD1 Infections of Alfalfa Seedlings.

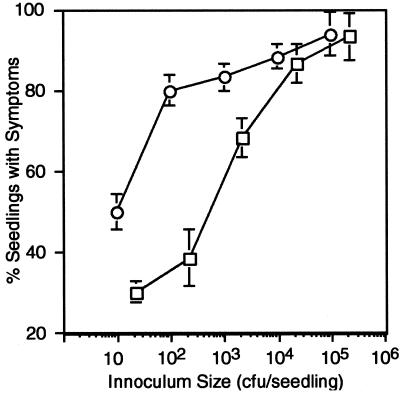

As few as 20 bacterial cells of PAO1 or FRD1 were sufficient to infect some seedlings and produce disease. There was also a positive correlation between the inoculum size and the number of seedlings that exhibited disease symptoms (Fig. 3). However, PAO1 was more virulent and consistently infected a higher percentage of alfalfa seedlings at each inoculum level as compared with FRD1. Disease symptoms with PAO1 were also more severe than with FRD1 in that the infected plants showed more tissue maceration. To determine whether this reflected the ability of each strain to grow in planta, bacteria were recovered from individual infected seedlings and were plated to count for cfu. Interestingly, the number of bacteria recovered from an infected seedling was relatively constant for a given strain, regardless of the original inoculum size. PAO1 and FRD1 produced ≈2.27 × 109 (±23%) and 4.43 × 108 (±22%) cfu per seedling, respectively. Thus, ≈5-fold more bacteria were typically recovered from PAO1 infections as compared with FRD1-infected seedlings (P < 0.0001). The seedlings infected with FRD1 were visibly covered in a viscous layer of alginate (Fig. 2B), accumulating ≈145 μg of alginate per seedling by day 7. Even though alginate production by mucoid P. aeruginosa is typically an unstable characteristic (41), >90% of the bacteria recovered from FRD1-infected seedlings retained their mucoid phenotype. Over 90% of the bacteria recovered from the plants infected with the other mucoid CF strains (DO60 and DO139) also retained their mucoid phenotype (data not shown). Thus, interactions with the plant host may promote stability of alginate production by mucoid CF isolates of P. aeruginosa.

Fig 3.

Effect of inoculum size on the frequency of infection. Values show the average fraction (percentage ± SE) of the seedlings showing disease symptoms after inoculation of ≈10–105 bacteria per plant; 60 plants per infection dose were tested. Data are the average of three experiments testing nonmucoid strain PAO1 (○) and mucoid strain FRD1 (□).

Alfalfa Infection with Derivatives of CF Strain FRD1.

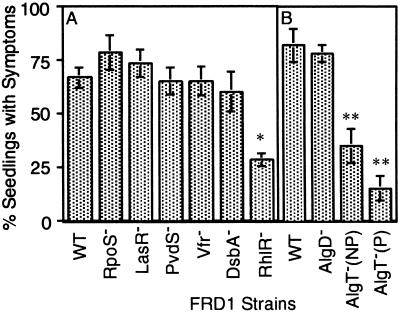

We took a predictive approach to identify virulence factors important for disease in alfalfa seedlings. Recently, disulfide bond isomerase, encoded by dsbA, was found to contribute to the virulence of a nonmucoid P. aeruginosa strain in an alternative model system (19, 23). However, our FRD1dsbA mutant was not obviously affected in its ability to cause disease on wounded alfalfa seedlings. Several global regulators that control the expression of multiple virulence determinants have been described as playing a role in the virulence of P. aeruginosa (19, 30, 42–47). Mutants of FRD1 were constructed with specific defects in several global regulators (see Methods). Using a constant inoculum size of ≈1,000 bacterial cells per wounded seedling, we examined the effects of mutations in the genes for the catabolite activator protein-like global regulator Vfr, for sigma factors RpoS and PvdS, and for the quorum sensor regulators LasR and RhlR. Among these FRD1 derivatives, only the RhlR-defective mutant displayed an obvious reduction in virulence based on the percent of seedlings with disease symptoms (Fig. 4A). For each of the FRD1 derivatives tested, the number of bacteria recovered from diseased seedlings was compared, but there was no significant difference (data not shown). Thus, once each of these FRD1 derivatives had established an infection, it grew as well as the parental strain in planta. In that the loss of RhlR reduced the pathogenesis of strain FRD1 suggests that the alfalfa infection model could be used to identify virulence determinants.

Fig 4.

Effect of specific mutations on virulence of FRD1 in alfalfa. Values show the average fraction (percentage ± SE) of the seedlings showing disease symptoms when 60 wounded seedlings were inoculated with ≈103 bacteria. (A) Strain FRD1 derivatives tested include the WT mucoid strain and mutants with specific defects in rpoS, lasR, pvdS, vfr, dsbA, and rhlR. (B) In a separate set of experiments, strain FRD1 and mutants with defects in algD, algT (nonpolar, NP), and algT (polar, P) were tested. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001.

The obvious distinguishing feature among CF isolates like FRD1 is their highly mucoid phenotype, which is rare in other clinical and environmental isolates. Among the mucoid FRD1 derivatives tested above, >97% of the bacteria recovered from the infected seedlings retained their original mucoid phenotype, suggesting a possible role for alginate. Thus, to determine whether alginate production was important for pathogenesis on alfalfa seedlings, we examined an algD:Tn501 polar mutant, which is defective for production of alginate. However, this alginate-defective mutant showed no reduction in the percent of diseased seedlings as compared with mucoid FRD1. Thus, alginate production was apparently not essential for FRD1 to establish an infection in the alfalfa model. Also, ≈3.5-fold more bacteria were recovered from the algD mutant-infected seedlings as compared with parent FRD1-infected seedlings (P < 0.01, data not shown), suggesting alginate production actually attenuated the growth of P. aeruginosa on these wounded plant tissues.

Like many CF isolates, the mucoid phenotype of FRD1 is due to a mutation in mucA, encoding an anti-sigma factor of algT-encoded sigma-22. Recent proteomic studies demonstrate that genes other than those for alginate are also up-regulated when MucA is defective, including dsbA (31). Nonmucoid derivatives of FRD1 with mutations in algT (with nonpolar and polar mutations) were dramatically reduced in virulence compared with the parental strain (Fig. 4B). However, when infections did occur with algT mutants, the disease symptoms observed and number of bacteria recovered were comparable to those with parental FRD1 (data not shown). Thus, AlgT apparently controls the expression of unknown virulence determinants (other than alginate and DsbA) that play a major role in the initiation, but not maintenance, of this pathogenic process.

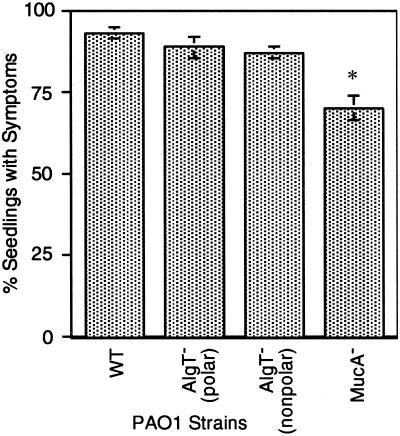

Alfalfa Infection by Derivatives of PAO1 Altered in AlgT.

To further test the in vivo roles of alginate and its main regulator, AlgT (also known as AlgU, σ22, and σE), we examined a mucoid variant of PAO1 called PDO300 (36) that carries a defect in anti-sigma factor, MucA. When an inoculum size of ≈100 bacterial cells per wounded seedling was used, the parent strain PAO1 caused disease in ≈90% of wounded seedlings, whereas the isogenic mucA mutant was less virulent, producing disease in ≈75% of the wounded seedlings (Fig. 5). Thus, consistent with the results above in strain FRD1, the production of alginate did not enhance the virulence of PAO1 in this infection model. The mucoid phenotype of mucA-defective PAO1 was not stable in planta with 10–90% nonmucoid colonies from individual alfalfa seedlings. We observed unusually high variability in the number of bacteria recovered from PAO1mucA-infected seedlings (i.e., 3.35 × 108 to 1.6 × 109 cfu per seedling). This suggests that a deregulated AlgT adversely affected the ability of PAO1 to initiate an infection. To test the role of sigma-22 directly, algT mutants of PAO1 were assayed for virulence, but no obvious defect in the ability to cause disease on wounded alfalfa seedlings was observed (Fig. 4B). This finding was in contrast to the dramatic reduction in virulence caused by algT mutation in CF isolate FRD1. These results suggest that the pathogenic mechanisms of strains adapted to the CF lung environment are primarily AlgT dependent, whereas PAO1 retains dominant mechanisms for pathogenesis that are not controlled by AlgT.

Fig 5.

Effect of specific mutations on virulence of PAO1 in alfalfa. Values show the average fraction (percentage ± SE) of the seedlings showing disease symptoms when 60 wounded seedlings were inoculated with ≈102 bacteria. Strain PAO1 derivatives tested include the WT nonmucoid strain and mutants with specific defects in algT (polar), algT (nonpolar), and mucA. *, P < 0.01.

Discussion

It has long been recognized that P. aeruginosa strains isolated from sputum samples of CF patients differ from other P. aeruginosa strains, but it has not been fully appreciated how this can affect pathogenesis. Although most CF strains acquire the dramatic mucoid phenotype, they also typically undergo a reduction or loss of other classic virulence determinants including O side chains of LPS, proteases, toxins, and motility (4, 8, 10, 12, 14, 40). Thus, perhaps there is an in vivo selection for P. aeruginosa variants in the CF lung that are reduced in virulence to promote persistence that can result in a chronic infection. It is remarkable how CF patients can carry such a high bacterial load of P. aeruginosa in their lungs for decades and with the same mucoid strain. In contrast, a human burn wound infection with P. aeruginosa can be swift and deadly. Despite the reduced virulence, chronic infection with mucoid Pseudomonas in the CF lung is incurable and ultimately leads to loss of lung function and death. Thus, it is important to identify virulence determinants peculiar to CF isolates of P. aeruginosa that permit them to thrive as long-term, destructive disease agents.

Unfortunately, the identification of new virulence factors in nontypeable CF strains is difficult because they are often attenuated in classic animal models of P. aeruginosa infection due to their defects in LPS O side chains. For instance, we show here that a nontypeable mucoid CF isolate, FRD1, was nearly avirulent in one of the most commonly used chronic lung infection models currently available. To begin to identify additional virulence determinants in CF strains, we developed an alternative model of infection, based upon wounded alfalfa seedlings. This model was sufficiently sensitive to show disease symptoms after infection at low infectious doses and with a variety of CF strains. In addition, the model system was simple, rapid, cost-effective, and required no special equipment.

For an alternative infection model to be useful, it had to be able to discriminate a reduced virulence phenotype if the appropriate bacterial gene was mutated. Thus, we tested FRD1 derivatives with specific defects in the regulators Vfr, RpoS, PvdS, LasR, and RhlR. These factors are known to control expression of many virulence gene products, although their potential roles in CF lung infection are currently unclear. We found that only RhlR contributed significantly to the virulence of FRD1 in the alfalfa model. Quorum sensing regulators like RhlR have also been shown to be important for the virulence of typical P. aeruginosa strains in animal models (48). Our alternative model system was used to identify virulence genes in a nontypeable mucoid CF isolate of P. aeruginosa and represents another step toward understanding the unique pathogenic mechanisms of CF isolates. It was interesting that the other regulators of virulence examined (i.e., Vfr, RpoS, PvdS, LasR) were not required for virulence by LPS-defective FRD1, suggesting that a different repertoire of virulence determinants may play a role. Sigma factor PvdS controls pyoverdine production (32), but this siderophore was not required for FRD1 virulence in this model system, perhaps due to the absence of competing bacteria.

The pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa in CF has largely been attributed to the copious production of the exopolysaccharide alginate. Roles for alginate in pathogenesis include suppression of opsonic antibody production (49, 50), inhibition of phagocytosis (51), quenching of oxygen radicals (52), and increasing resistance to antibiotics (53). In the plant pathogen, Pseudomonas syringae, a positive correlation exists between alginate and virulence on beans and survival on the plant surface (54, 55). The importance of alginate production by P. aeruginosa has not yet been directly demonstrated in an animal infection model (2, 3). However, a chronic pulmonary infection model can induce conversion of strain PAO1 to the mucoid phenotype, suggesting a role in pathogenesis (40).

A P. aeruginosa FRD1 algD mutant defective for alginate biosynthesis still caused disease in wounded alfalfa seedlings, so alginate was not required. This result was in agreement with Yorgey et al. (56) that alginate is not required for the virulence of P. aeruginosa strain PA14 on plants, nematodes, and mice. Alginate presumably plays a role in CF lung pathogenesis that has no mimic in the alfalfa wound infection. For instance, recent studies show that CF patients elicit antibodies to mucoid Pseudomonas, but they are nonopsonic and ineffective at eliminating the bacteria due to the acetylated nature of bacterial alginate (50). It was also interesting that we recovered 3.5-fold more bacteria from the algD mutant-infected seedlings as compared with parent FRD1-infected seedlings, suggesting that the production of alginate actually attenuated the growth of P. aeruginosa on wounded plant tissues. This finding may have a parallel in the CF lung infection, where strains are sufficiently attenuated to cause chronic infections rather than acutely lethal ones. Nevertheless, the recovery of mucoid CF strains from alfalfa seedlings postinfection, despite its inherent instability (41), suggests a selective pressure to maintain the mucoid phenotype.

In contrast, algT mutants of FRD1 were severely reduced for virulence in the alfalfa model, which was apparently not just due to the alginate defect. This finding demonstrates that AlgT (σ22) is required for virulence in an infection model. The algT polar mutant was slightly more attenuated for virulence than the nonpolar mutant. Downstream of algT are the mucABCD genes, whose expression would be affected by a polar mutation in algT, and a MucD (HtrA homologue) defect in strain PA14 affects virulence in plants, animals, and nematodes (56). Thus, AlgT apparently controls the expression of an unknown virulence factor in FRD1 required to cause disease in this model. Rhamnolipids are under RhlR control, but the FRD1algT mutant still produced rhamnolipids (data not shown). AlgT (σ22) controls the expression of periplasmic disulfide bond isomerase (31), and dsbA mutants of strain PA14 are affected for virulence (19). Type IV pillus formation also depends on DsbA in P. aeruginosa (31). However, a dsbA mutant of FRD1 was not obviously affected for virulence in the alfalfa model. Thus, there is apparently a virulence factor under AlgT control, which is currently unknown.

Although FRD1 algT mutants were severely reduced for infection of alfalfa seedlings, a PAO1 algT mutant was not. In a mouse model of acute infection, algT (algU) mutation in PAO1 causes an increase in systemic virulence (57). Conversely, a mucA-defective PAO1, which has high AlgT activity, demonstrated a reduced ability to cause disease on alfalfa, possibly because of the drain of energy and carbon to produce exopolysaccharide. In vivo selection for mucA mutants of P. aeruginosa in the CF lung may in part be driven by the fact that attenuating virulence promotes a chronic infection. However, alginate probably plays a direct role in CF pathogenesis that is not duplicated in this plant model. Our comparison of CF and non-CF strains suggests that AlgT controls a virulence factor important in an attenuated, nontypeable CF strain that is masked in other strains. The wounded alfalfa model provides an attractive system to discover such virulence determinates important to pathogenesis in CF.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc. for the gift of alfalfa seeds that were used in this study. We also thank D. E. Woods for quantitative histopathology analyses and the Medical College of Virginia Pathogenesis Group for helpful discussions. This work was supported by Public Health Service Grant AI-19146 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (to D.E.O.), Veterans Affairs Medical Research funds (to D.E.O), Grant MOP-45210 from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (to P.A.S), and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship SUH96F0 (to S.-J.S.).

Abbreviations

CF, cystic fibrosis

cfu, colony-forming unit(s)

LPS, lipopolysaccharide

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Govan J. R. & Nelson, J. W. (1992) Br. Med. Bull. 48 912-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cash H. A., Woods, D. E., McCullough, B., Johanson, W. G. & Bass, J. A. (1979) Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 119 453-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods D. E. & Bryan, L. E. (1985) J. Infect. Dis. 151 581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hancock R. E., Mutharia, L. M., Chan, L., Darveau, R. P., Speert, D. P. & Pier, G. B. (1983) Infect. Immun. 42 170-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penketh A., Pitt, T., Roberts, D., Hodson, M. & Batten, J. (1983) Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 127 605-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luzar M. A. & Montie, T. C. (1985) Infect. Immun. 50 572-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cryz S. J., Fürer, E. & Germanier, R. (1984) Infect. Immun. 44 508-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohman D. E. & Chakrabarty, A. M. (1982) Infect. Immun. 37 662-669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimwood K., Semple, R. A., Rabin, H. R., Sokol, P. A. & Woods, D. E. (1993) Pediatr. Pulmonol. 15 135-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallant C. V., Raivio, T. L., Olson, J. C., Woods, D. E. & Storey, D. G. (2000) Microbiology 146 1891-1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasil M. L., Chamberlain, C. & Grant, C. C. (1986) Infect. Immun. 52 538-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dacheux D., Attree, I. & Toussaint, B. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69 538-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luzar M. A., Thomassen, M. J. & Montie, T. C. (1985) Infect. Immun. 50 577-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahenthiralingam E., Campbell, M. E. & Speert, D. P. (1994) Infect. Immun. 62 596-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliver A., Canton, R., Campo, P., Baquero, F. & Blazquez, J. (2000) Science 288 1251-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang X., Pham, X. Q., Olson, M. V. & Lory, S. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183 843-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romling U., Schmidt, K. D. & Tummler, B. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 271 386-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tummler B., Bosshammer, J., Breitenstein, S., Brockhausen, I., Gudowius, P., Herrmann, C., Herrmann, S., Heuer, T., Kubesch, P., Mekus, F., et al. (1997) Behring Inst. Mitt. 98 249-255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahme L. G., Tan, M. W., Le, L., Wong, S. M., Tompkins, R. G., Calderwood, S. B. & Ausubel, F. M. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94 13245-13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Argenio D. A., Gallagher, L. A., Berg, C. A. & Manoil, C. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183 1466-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan M. W., Rahme, L. G., Sternberg, J. A., Tompkins, R. G. & Ausubel, F. M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 2408-2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jander G., Rahme, L. G. & Ausubel, F. M. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182 3843-3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan-Miklos S., Rahme, L. G. & Ausubel, F. M. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 37 981-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohman D. E. & Chakrabarty, A. M. (1981) Infect. Immun. 33 142-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Handelsman J., Raffel, S., Mester, E. H., Wunderlich, L. & Grau, C. R. (1990) Ann. Embryol. Morphog. 56 713-718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holloway B. W., Krishnapillai, V. & Morgan, A. F. (1979) Microbiol. Rev. 43 73-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stover C. K., Pham, X. Q., Erwin, A. L., Mizoguchi, S. D., Warrener, P., Hickey, M. J., Brinkman, F. S. L., Hufnagle, W. O., Kowalik, D. J., Lagrou, M., et al. (2000) Nature 959 959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Speert D. P., Farmer, S. W., Campbell, M. E., Musser, J. M., Selander, R. K. & Kuo, S. (1990) J. Clin. Microbiol. 28 188-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chitnis C. E. & Ohman, D. E. (1993) Mol. Microbiol. 8 583-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suh S. J., Silo-Suh, L., Woods, D. E., Hassett, D. J., West, S. E. & Ohman, D. E. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181 3890-3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malhotra S., Silo-Suh, L. A., Mathee, K. & Ohman, D. E. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182 6999-7006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunliffe H. E., Merriman, T. R. & Lamont, I. L. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177 2744-2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schweizer H. D. (1993) BioTechniques 15 831-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selvaraj G., Fong, Y. C. & Iyer, V. N. (1984) Gene 32 235-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schweizer H. P. (1992) Mol. Microbiol. 6 1195-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathee K., Ciofu, O., Sternberg, C., Lindum, P. W., Campbell, J. I., Jensen, P., Johnsen, A. H., Givskov, M., Ohman, D. E., Molin, S., et al. (1999) Microbiology 145 1349-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knutson C. A. & Jeanes, A. (1968) Anal. Biochem. 24 470-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunnil M. S. (1962) Thorax 17 320-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sokol P. A. & Woods, D. E. (1984) J. Med. Microbiol. 18 125-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woods D. E., Sokol, P. A., Bryan, L. E., Storey, D. G., Mattingly, S. J., Vogel, H. J. & Ceri, H. (1991) J. Infect. Dis. 163 143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeVries C. A. & Ohman, D. E. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176 6677-6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brint J. M. & Ohman, D. E. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177 7155-7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson J. P., Feldman, M., Iglewski, B. H. & Prince, A. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68 4331-4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rumbaugh K. P., Griswold, J. A., Iglewski, B. H. & Hamood, A. N. (1999) Infect. Immun. 67 5854-5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang H. B., DiMango, E., Bryan, R., Gambello, M., Iglewski, B. H., Goldberg, J. B. & Prince, A. (1996) Infect. Immun. 64 37-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West S. E., Sample, A. K. & Runyen-Janecky, L. J. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176 7532-7542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiong Y. Q., Vasil, M. L., Johnson, Z., Ochsner, U. A. & Bayer, A. S. (2000) J. Infect. Dis. 181 1020-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Kievit T. R. & Iglewski, B. H. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68 4839-4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cryz S. J., Furer, E. & Que, J. U. (1991) Infect. Immun. 59 45-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pier G., Coleman, F., Grout, M., Franklin, M. & Ohman, D. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69 1895-1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliver A. M. & Weir, D. M. (1985) Clin. Exp. Immunol. 59 190-196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simpson J. A., Smith, S. E. & Dean, R. T. (1989) Free Radical Biol. Med. 6 347-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allison D. G. & Matthews, M. J. (1992) J. Appl. Bacteriol. 73 484-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osman S. F., Fett, W. F. & Fishman, M. L. (1986) J. Bacteriol. 166 66-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu J., Penaloza-Vazquez, A., Chakrabarty, A. M. & Bender, C. L. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 33 712-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yorgey P., Rahme, L. G., Tan, M. W. & Ausubel, F. M. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 41 1063-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu H., Boucher, J. C., Hibler, N. S. & Deretic, V. (1996) Infect. Immun. 64 2774-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]