Abstract

Transformation of Solanum tuberosum, cv. Desiree, with the tomato prosystemin gene, regulated by the 35S cauliflower mosaic virus promoter, resulted in constitutive increase in defensive proteins in potato leaves, similar to its effects in tomato plants, but also resulted in a dramatic increase in storage protein levels in potato tubers. Tubers from selected transformed lines contained 4- to 5-fold increases in proteinase inhibitor I and II proteins, >50% more soluble and dry weight protein, and >50% more total nitrogen and total free amino acids than found in wild-type tubers. These results suggest that the prosystemin gene plays a dual role in potato plants in regulating proteinase inhibitor synthesis in leaves in response to wounding and in regulating storage protein synthesis in potato tubers in response to developmental cues. The results indicated that components of the systemin signaling pathway normally found in leaves have been recruited by potato plants to be developmentally regulated to synthesize and accumulate large quantities of storage proteins in tubers.

Keywords: tomato, systemic wound signaling, storage proteins, defense response

Proteinase inhibitors I and I (Inh I and II) proteins were initially found as major storage proteins in potato tubers (1–3) and later as wound-inducible antinutrient defensive proteins in leaves of several Solanaceae species (4, 5). The two proteins can account for up to 10% of the total soluble proteins of mature potato tubers (6, 7) and up to 2% of the soluble proteins in leaves of tomato plants in response to mechanical wounding or herbivore attacks. The wound-inducible expression of Inh I and II in tomato and potato leaves has been extensively investigated (5, 8), and their synthesis was shown to be initiated by the release of a mobile 18-aa polypeptide signaling molecule called systemin (9). Systemin is released from damaged cells at the site of wounding and systemically activates the expression of over 20 defense-related genes, including Inh I and II, in leaves throughout the plants (5). Systemin is synthesized as part of a larger 200-aa protein called prosystemin (10), whose cDNA has been overexpressed in transgenic tomato plants in both the antisense and sense orientations. In the antisense plants, systemic wound signaling does not occur (10), whereas in the sense plants, the leaves constitutively express high levels of the wound-inducible defensive proteins in the absence of wounding, acting as if the plants were in a permanent wounded state (11).

Although Inh I and II were first discovered in potato tubers (1), systemin had not been considered previously to be involved in the regulation of tuber storage proteins. We have now constitutively overexpressed the tomato prosystemin gene in potato plants in its sense orientation, similar to previous experiments with tomato plants (11). The transgenic plants overexpressing the prosystemin gene were found to regulate not only the synthesis and accumulation of proteinase inhibitors in leaves but also the synthesis of major storage proteins in potato tubers. Tubers from selected transgenic potato lines were found to contain highly elevated levels of soluble proteins, including Inh I and II and patatin, over tubers from untransformed wild-type plants. The evidence suggests that as potato plants evolved tubers for reproduction, wound-inducible defense-signaling pathway components in leaves and stems were recruited to provide a mechanism to store proteins in tuber cells for vegetative propagation.

Materials and Methods

Potato Transformation.

A previously constructed chimeric cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV)–tomato prosystemin gene was used that contained a cDNA fragment encoding the complete tomato prosystemin ORF fused in the sense orientation with the 35S CaMV promoter within the binary vector pGA 643. The physical map of this chimeric gene and details on its construction have been reported (11). This construct was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LA 4404 and was used to transform potato leaf and tuber tissues. Both leaf and potato tuber discs were surface sterilized and preconditioned by incubating for 2 days in tobacco feeder plates and were then soaked for 20–30 min in 10–20 ml of Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (MS salts/B5 vitamins/100 mg/liter m-inositol/3% sucrose, pH 5.9), containing 107 Agrobacterium cells per ml. The explants were blotted dry with sterile filter paper and incubated again on tobacco feeder plates for another 2 days and then transferred to potato cell culture medium (MS medium/5 μM zeatin/3 μM indoleacetic acid/0.7% agarose), containing 250 mg/ml Cefotaxime. The small calli that grew from the explants after 2–3 weeks were transferred to fresh potato medium containing 100 mg/liter kanamycin. The explants were transferred to fresh medium every 2 weeks (growing calli were separated from the rest of the explant) until the first well-differentiated shoots appeared (after 4–6 weeks). The level of kanamycin in the medium was gradually reduced to allow rooting, first to 50 mg/liter and then to 20 mg/liter. Regenerated plants were transferred to soil and grown to maturity in a greenhouse.

Proteinase Inhibitor Assays.

Inh I and II proteins were quantified by immunoradial diffusion (12, 13) by using pure potato inhibitors I and II as standards. Juice was expressed from leaves and tubers of control (wild-type) and transgenic plants. A transverse section (about one-quarter of an inch in width) was excised from the center of each tuber, including cortical and pith tissue. The section was diced into small pieces and crushed with mortar and pestle to express the juice. The juice was collected in a microfuge tube kept on ice and centrifuged at 10,500 × g to clarify. Centrifugation had no effect on the levels of Inh I and II in the juice. Inhibitor concentration was expressed in microgram per milliliter of extracted juice.

RNA Extraction and Analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from leaves and tubers of wild-type and transgenic plants. The leaves were immersed in liquid nitrogen, ground to a fine powder, and stored at −80°C until used. Total leaf RNA was extracted by using the Trizol reagent (GIBCO/BRL) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Potato tubers were chopped in small pieces, frozen with liquid nitrogen, ground to a fine powder with a mortar and pestle, and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was then extracted according to Singh et al. (14), with some modifications. Briefly, ≈100 mg of ground tuber tissue was extracted with a mix of 400 μl of 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1% (wt/vol) sodium sulfite and 500 μl of water-saturated phenol, and reextracted with an equal volume of acid–phenol/chloroform (5:1, Ambion, Austin, TX). The RNA was precipitated with equal volumes of isopropanol containing 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) at −20°C overnight. RNA quality was determined by gel fractionation in agarose formaldehyde followed by ethidium bromide staining and UV light visualization before analyzing for specific mRNAs. A tomato prosystemin cDNA, Inh I and II cDNAs, and an RT-PCR-amplified patatin cDNA from potato tissue were used as probes in gel blot analyses as described (15). An 18S ribosomal RNA gene probe was used as a loading control. Membranes were washed once with 2× SSPE (1 × 0.115 M NaCl/10 mM NaH PO4/mM EDTA, pH 7.4) for 20 min at room temperature, two to three times with 2× SSPE/1% SDS, for 15–30 min at 65°C and then exposed 15–32 h to x-ray film or to a PhosphorImager (Bio-Rad).

Determination of Tuber Percent Nitrogen.

Fresh tubers (100–200 g each) from second-generation-propagated wild-type and transgenic potato plants grown in a greenhouse were selected for total nitrogen analysis. Tubers were diced into small pieces and freeze-dried. Once dried, tuber pieces were ground to a fine powder, weighed, and analyzed for percent nitrogen, dry weight, by using a LECO combustion analyzer CNS-2000 (LECO, St. Joseph, MI) (16), at the Analytical Sciences Laboratory, University of Idaho Holm Research Center, Moscow, ID.

Statistical Analysis.

One-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test was performed to compare mean values of inhibitor protein levels and nitrogen content in the tubers from wild-type and transgenic plants.

Results and Discussion

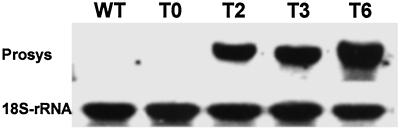

The constitutive overexpression of the prosystemin gene in the leaves of transgenic plants was confirmed in gel blot analyses of prosystemin mRNA by using the tomato prosystemin cDNA as a probe. In 18 transformants that were regenerated, various levels of expression of the prosystemin gene were found. Prosystemin mRNA blots from leaves of the three transformants T2, T3, and T6 that expressed the highest levels of the prosystemin mRNA are shown in Fig. 1. Prosystemin mRNA was not detected in leaves of either the wild-type or in the transformed control plants, but in assays at lower stringency, low levels of prosystemin mRNA could be detected, similar to levels found in leaves of wild-type tomato plants (10).

Fig 1.

Constitutive expression of the tomato prosystemin gene in leaves of transgenic potato plants. WT, wild-type control plant; T0, transgenic control plant transformed with a plasmid lacking the prosystemin gene; T2, T3, and T6, transgenic plants. An 18S ribosomal RNA gene probe was used as a loading control.

Immunological assays of the levels of Inh I and II proteins in the expressed juice of leaves of the young transgenic plants also identified T2, T3, and T6 transformants as having high levels of proteinase inhibitors (Table 1). The levels of proteinase inhibitors in leaves of these three transformants ranged from 4- to 5-fold higher than levels in leaves of wild-type plants or in leaves of the transgenic control plants lacking the prosystemin transgene. The constitutive expression of the two inhibitors was similar to their expression in leaves of tomato plants that were transformed with the prosystemin gene (11), where the overexpression of the prosystemin gene caused the constitutive expression of several wound- and systemin-inducible genes, as if the plants were under constant herbivore attacks (11, 17). The effect appears to be caused by the abnormal elevated synthesis and processing of prosystemin, resulting in the release of systemin throughout the plants.

Table 1.

Levels of Inh I and II in juice from leaves of first-generation transgenic potato plants overexpressing the tomato prosystemin gene

| Plant | Inh I, μg/ml leaf juice | Inh II, μg/ml leaf juice | Total, μg/ml leaf juice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type control | 34 | 15 | 49 |

| Transgenic control | 23 | 20 | 43 |

| T2 | 75 | 77 | 152 |

| T3 | 90 | 87 | 177 |

| T6 | 110 | 100 | 210 |

Inh I and II proteins were quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Values are the average values of two measurements per plant; each measurement was made by using pooled juice from at least two leaves.

Control plants transformed with a plasmid lacking the prosystemin gene.

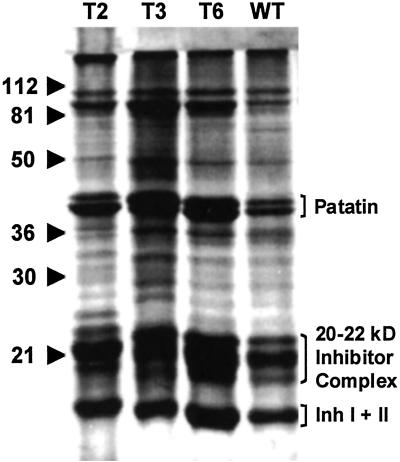

Assays for Inh I and II proteins in the juice from the transgenic tubers also revealed that the proteins were present at strikingly high levels, averaging about a 2.5-fold increase for both inhibitors over levels found in wild-type tubers (Table 2). To determine whether levels of other proteins present in the tuber juice of transformants T2, T3, and T6 were also elevated, the juice was analyzed by SDS/PAGE. The protein profiles of juice from these tubers are compared in Fig. 2 with proteins from the expressed juice from wild-type tubers. The levels of Inh I, Inh II, and other storage proteins, including patatin and a group of proteinase inhibitors of molecular masses near 20 kDa (18), showed pronounced increases over the proteins of the control plants. Differences in the levels of individual proteins were found among transgenic lines, indicating that a differential regulation of storage proteins by prosystemin may be occurring, perhaps resulting from insertional effects during transformation and/or somaclonal variations that occurred during regeneration of plants (19).

Table 2.

Inh I and II and soluble protein levels in juice expressed from wild-type and transgenic potato tubers

| Plant

|

Inh I | Inh II | Soluble protein | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/ml | % | μg/ml | % | μg/ml | % | |

| Wild-type | 234 | 100 | 351 | 100 | 2.8 | 100 |

| T2 | 538 | 230 | 970 | 277 | 5.2 | 185 |

| T3 | 626 | 267 | 851 | 242 | 5.4 | 193 |

| T6 | 590 | 252 | 930 | 265 | 4.7 | 168 |

Inh I and II proteins were quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Total water-soluble proteins in the clarified juice were assayed by using the Bradford assay, with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Shown are average values from six independent assays.

Fig 2.

SDS/PAGE analysis of soluble proteins in tubers from transgenic potato plants T2, T3, and T6, transformed with the tomato prosystemin gene, and from tubers from wild-type plants (WT). Clarified juice from tubers (30 μl) was mixed with 10 μl of 4× Laemmli's sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and loaded into 12.5% polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis, the protein profiles were visualized with Coomassie blue.

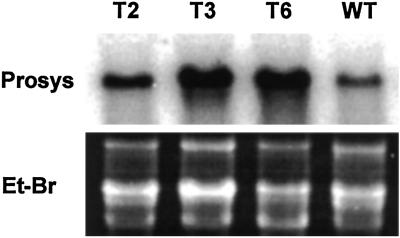

Small tubers from plants of transgenic lines T2, T3, and T6 were used to propagate second generations in larger pots in the greenhouse, supplemented with lights. Five tubers (50–120 g) from each transgenic line and from wild-type control plants were assayed for prosystemin expression (Fig. 3). The assays indicated that the prosystemin transgene was strongly expressed in the tubers, similar to its expression in the leaves.

Fig 3.

Gel blot analyses of tomato prosystemin mRNA in tubers from wild-type (WT) and transgenic potato plants T2, T3, and T6. Et-Br, ethidium bromide-stained ribosomal RNA used as loading control.

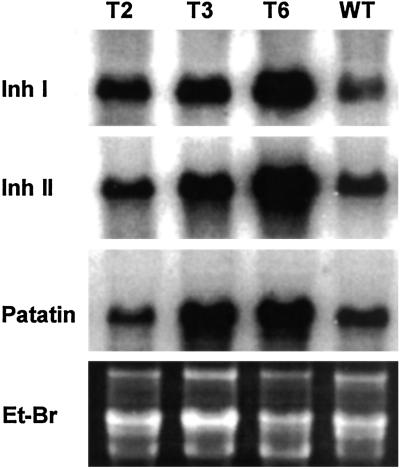

The increased expression of Inh I and II and patatin genes in the tubers was confirmed by gel blot analyses of their respective mRNAs (Fig. 4). All three genes were expressed at substantially higher levels than in wild-type tubers. This observation suggested that the expression of the prosystemin gene in the tubers resulted in the transcriptional regulation of the storage protein genes.

Fig 4.

Gel blot analyses of mRNAs coding for Inh I, Inh II, and patatin, in second-generation tubers from wild-type (WT) and transgenic potato plants T2, T3, and T6. Et-Br, ethidium bromide-stained ribosomal RNA used as loading control.

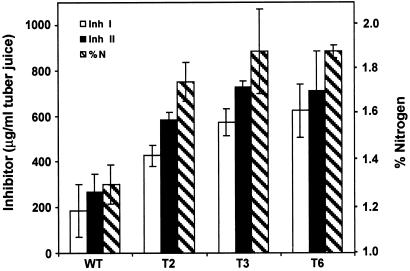

The increases in the levels of storage proteins in the tubers were reflected in increases in total soluble proteins. In transgenic tubers, the levels of soluble proteins were 4.7–5.4 mg/ml, compared with 2.8 ± 0.9 mg/ml in tubers from wild-type plants (Table 2). Increases in total soluble protein were accompanied by an increase in percent total nitrogen. The average percent dry weight nitrogen in the tubers from transgenic plants was 1.7–1.9%, compared with ≈1.3 ± 0.1% in tubers from wild-type plants (Fig. 5). Mean values of inhibitor levels and percent nitrogen in tubers of each of the transgenic plants were significantly higher (P < 0.001) than levels found in the tubers of wild-type plants (Fig. 5). Because free amino acids can represent a substantial contribution to potato tuber nitrogen (20), the free amino acid pool was analyzed in the tubers of the transgenic lines. Free amino acids in the transgenic tubers ranged 5.3–6.8 μmol/100 mg of dry weight compared with 4.2 μmol/100 mg of dry weight in wild-type tubers, with glutamine exhibiting increases of 2.5- to 2.9-fold (Table 3). This indicated that the increased synthesis of storage proteins in the tubers was not limited by amino acid availability, and that the expression of the prosystemin gene had caused the amino acid pools to increase to accommodate the increased synthesis of storage proteins.

Fig 5.

A comparison of the levels of Inh I and II proteins with the percent dry weight nitrogen in second-generation tubers from wild-type (WT) and transgenic potato plants T2, T3, and T6. Data are means ± SD (n = 6). Mean values for the transgenic plants were statistically different from the wild-type plants (Dunnett's test, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Levels of free amino acids in potato tubers from wild-type and transgenic plants

| Plant | Free amino acids | % increase | Glutamine | % increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 4.2 | 100 | 0.57 | 100 |

| T2 | 5.7 | 137 | 1.53 | 268 |

| T3 | 5.3 | 126 | 1.64 | 288 |

| T6 | 6.8 | 161 | 1.41 | 247 |

Free amino acids were extracted from lyophilized tuber tissue with acidified ethanol (80% ethanol/0.25 M HCl) at 40°C for 1 h and analyzed with a Beckman 6300 analyzer (GMI, Albertville, MN) using pure amino acids as standards.

μmol/100 mg of lyophilized tuber tissue.

The mechanism by which prosystemin regulates protein synthesis in tubers has not been established, but it is likely that signaling occurs through the octadecanoid pathway, as found in leaves, by producing oxylipin signals from linolenic acid (21) and active oxygen species (22). In leaves, systemin is processed from prosystemin and released on wounding, so that a developmentally regulated mechanism for systemin processing and release must be present in tubers. This might be accomplished by the synthesis of tuber-specific proteinases that are expressed constitutively. The prosystemin processing proteinases in leaves has not been identified, although several proteinases are wound- and systemin-inducible (5, 17) and may have roles in processing.

Inh I and II were initially isolated from potato tubers (1–3) and, because of their high concentrations, they were considered to be major storage proteins (23). A defensive role for the inhibitors in potato tubers has not been established but, as in leaves, they may have roles in defense against predators and pathogens. When denatured (cooked), potato tuber proteins are among the most nutritious plant proteins available to humans (24–26). They are a major source of dietary protein world-wide, with nearly 300 million tons of potatoes currently being produced on over 18 million hectares, representing over 6 trillion tons of protein (20, 27). Transformation of potatoes has become routine, even in developing countries. Thus, the potential for increasing the protein quantity of potato tubers of varieties grown in different countries, by the simple introduction of a constitutively expressed endogenous prosystemin gene, may provide a new source of inexpensive high-quality protein for animal and human consumption.

Studies of the systemin signaling system have revealed a new level of complexity in plants. Systemin signaling in tomato leaves has been shown to be mediated by a 160-kDa transmembrane leucine-rich repeat (LRR) receptor kinase that exhibits a high percentage of identity to the Arabidopsis brassinolide receptor BRI1 (28), indicating a possible dual function for this receptor in regulating both defense- and development-related genes. The relationship of systemin signaling with brassinolide signaling has become an intriguing question. Because of its ubiquity in plants (29), brassinolide signaling appears to have evolved much earlier than systemin signaling. Systemin signaling has been found in some species of the Solanaceae family but not others and is not found in other plant families. A role for systemin in tuberization in some potato species must have evolved at an even later time. Thus, it appears that the brassinolide receptor evolved initially and then was later recruited during the early evolution of the Solanaceae family to facilitate systemin signaling. As solanaceous species evolved, and tuberization from stems developed, some components of the systemin signaling pathway appear to have been adopted by cells of developing tubers as a means of storing proteins. Systemin signaling appears to be an interesting case of exaptation (30), the process of specific functions having evolved to a level where the process(es) is coopted to serve an entirely novel function in the organism.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Vogtman and C. Whitney for growing plants and G. Munske for amino acid analyses. This research was supported by the College of Agriculture and Home Economics and the National Science Foundation.

Abbreviations

Inh I and II, proteinase inhibitors I and II

References

- 1.Ryan C. A. & Balls, A. K. (1962) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 48 1839-1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melville J. C. & Ryan, C. A. (1972) J. Biol. Chem. 247 3445-3453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant J., Green, T., Gurusaddaiah, T. & Ryan, C. A. (1976) Biochemistry 15 3418-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green T. R. & Ryan, C. A. (1972) Science 175 776-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan C. A. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1477 112-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan C. A., Kuo, T., Pearce, G. & Kunkel, R. (1976) Am. Pot. J. 53 443-455. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan C. A. & Pearce, G. (1978) Am. Pot. J. 55 351-358. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leon J., Rojo, E. & Sanchez-Serrano, J. J. (2001) J. Exp. Bot. 52 1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearce G., Strydom, D., Johnson, S. & Ryan, C. A. (1991) Science 253 895-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGurl B., Pearce, G., Orozco-Cárdenas, M. & Ryan, C. A. (1992) Science 255 1570-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGurl B., Orozco-Cárdenas, M., Pearce, G. & Ryan, C. A. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 9799-9802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan C. A. (1967) Anal. Biochem. 19 434-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trautman R., Cowan, K. M. & Wagner, G. G. (1971) Immunochemistry 8 901-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh R. P., Nie, X., Singh, M., Coffin, R. & Duplessis, P. (2002) J. Virol. Methods 99 123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orozco-Cárdenas M. L., Narváez-Vásquez, J. & Ryan, C. A. (2001) Plant Cell 13 179-191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGeehan S. L. & Naylor, D. V. (1988) Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 19 493-505. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergey D., Howe, G. & Ryan, C. A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 12053-12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morelli J. K., Zhou, W., Yu, H., Lu, C. & Vayda, M. E. (1998) Plant Physiol. 116 1227-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birch R. G. (1997) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48 297-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liechti R. & Farmer, E. E. (2002) Science 296 1649-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orozco-Cárdenas M. L. & Ryan, C. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 6553-6557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan C. A. & Huisman, O. C. (1967) Nature 214 1047-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang D., Swanson, B. & Ryan, C. A. (1981) J. Food Sci. 46 287-270. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapoor A. C., Desborough, S. L. & Li, P. H. (1975) Pot. Res. 18 469-478. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuphan W. (1970) in Proteins as Human Food, ed. Lawrie, R. A. (Avi, Westport, CT), pp. 245–265.

- 26.Knorr D. (1978) Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 11 109-115. [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Potato Center (CIP) (1998) Potato Facts: A Compendium of Key Figures and Analysis for 32 Important Potato-Producing Countries (www.cipotato.org/Market/Potatofacts/potatofacts.htm).

- 28.Scheer J. M. & Ryan, C. A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 9585-9590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin Y., Wu, D. & Chory, J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 9090-9092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chipman A. D. (2001) Evol. Dev. 3 299-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]