Abstract

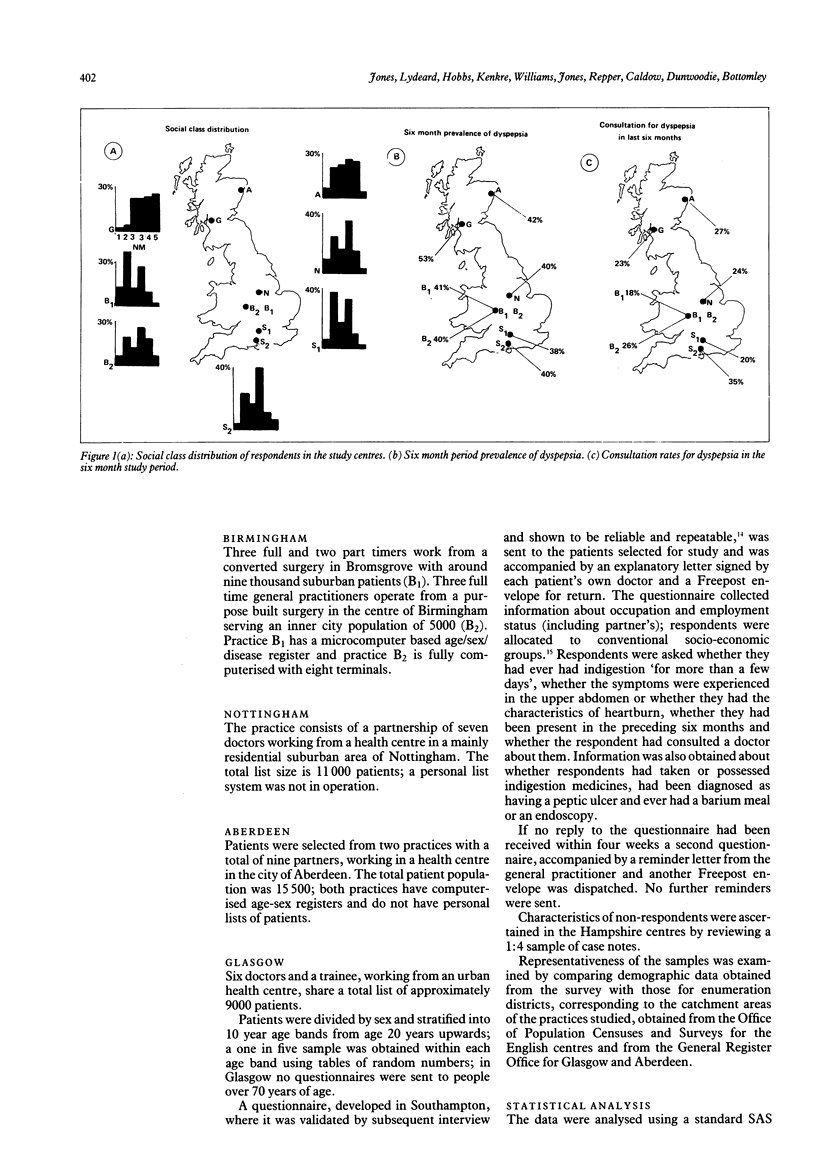

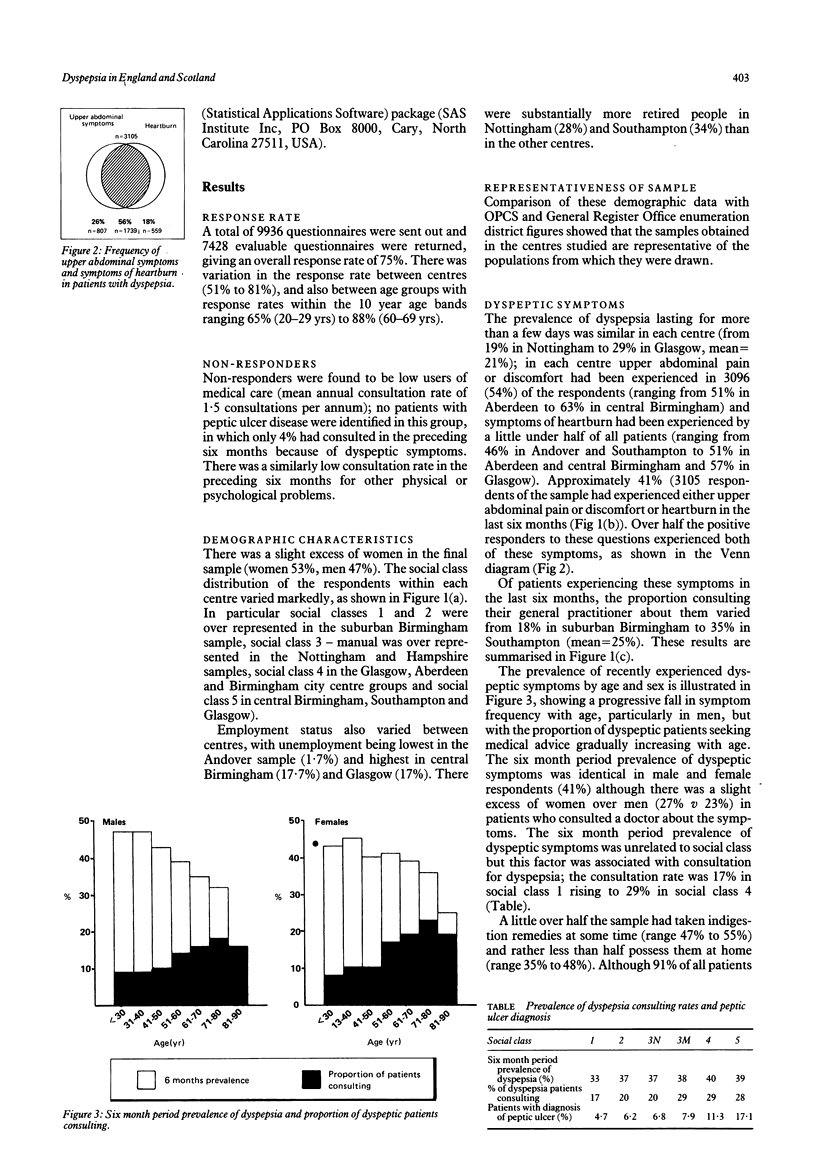

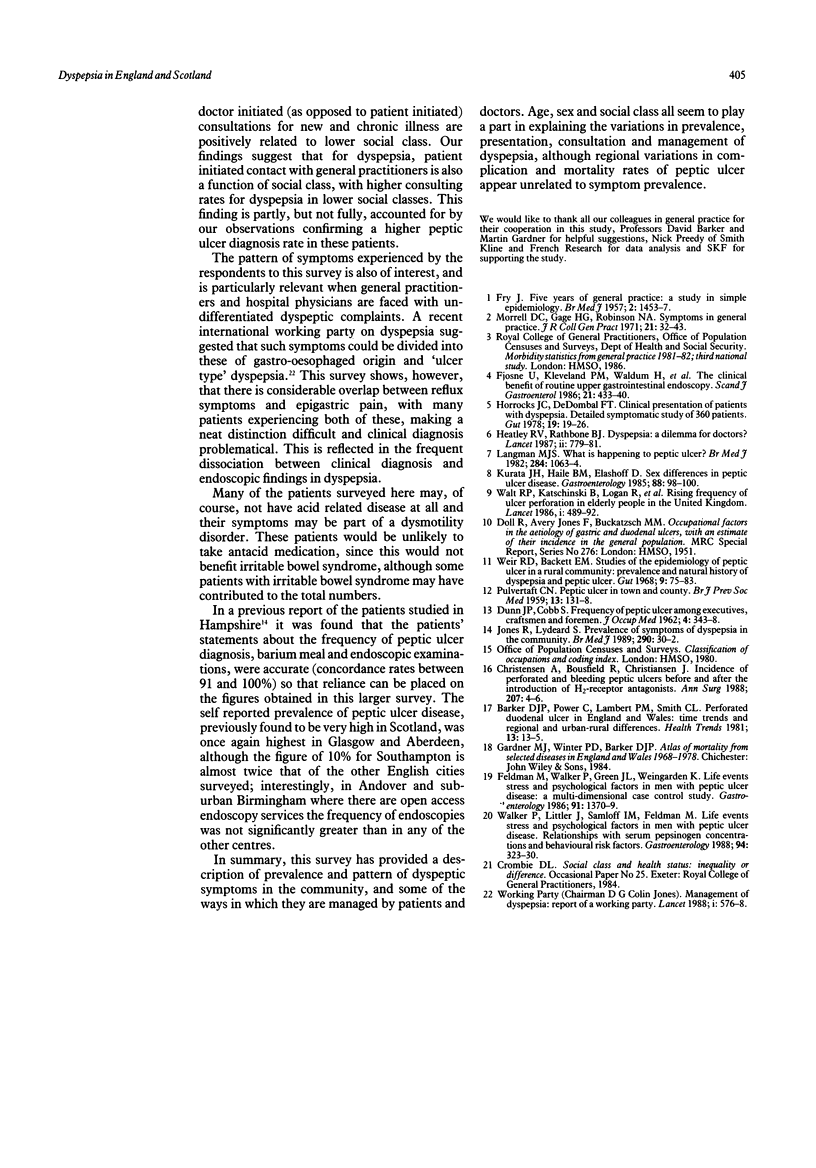

A validated postal questionnaire has been used to establish the prevalence of dyspeptic symptoms in five geographical locations from the south coast of England to the north of Scotland. The six month period prevalence of dyspepsia in the 7428 respondents to the questionnaire is 41% and equal between the sexes, with similar prevalence rates in the centres studied. There is considerable overlap between upper abdominal symptoms and symptoms of heartburn; 56% of patients with dyspepsia experience both groups of symptoms. Symptom frequency falls progressively with age in men and women, but the proportion of people seeking medical advice for dyspepsia rises with age. One quarter of the dyspeptic patients studied have consulted a general practitioner about their symptoms. This study suggests that the prevalence of dyspepsia in the community has changed little over the last 30 years, despite evidence that the frequency of peptic ulcer disease is falling. Symptom prevalence is unrelated to social class, but this factor is associated with consultation behaviour, the consultation rate rising from 17% in social class 1 to 29% in social class 4. The use of investigations--barium meal and endoscopy--is similarly related to social class; the lowest rate for ulcer diagnosis (4.7%) is found in social class 1 and the highest (17.1%) in social class 5.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Christensen A., Bousfield R., Christiansen J. Incidence of perforated and bleeding peptic ulcers before and after the introduction of H2-receptor antagonists. Ann Surg. 1988 Jan;207(1):4–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198801000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNN J. P., COBB S. Frequency of peptic ulcer among executives, craftsmen, and foreman. J Occup Med. 1962 Jul;4:343–348. doi: 10.1097/00043764-196207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRY J. Five years of general practice; a study in simple epidemiology. Br Med J. 1957 Dec 21;2(5059):1453–1457. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5059.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M., Walker P., Green J. L., Weingarden K. Life events stress and psychosocial factors in men with peptic ulcer disease. A multidimensional case-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1986 Dec;91(6):1370–1379. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjøsne U., Kleveland P. M., Waldum H., Halvorsen T., Petersen H. The clinical benefit of routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1986 May;21(4):433–440. doi: 10.3109/00365528609015159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatley R. V., Rathbone B. J. Dyspepsia: a dilemma for doctors? Lancet. 1987 Oct 3;2(8562):779–782. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks J. C., De Dombal F. T. Clinical presentation of patients with "dyspepsia". Detailed symptomatic study of 360 patients. Gut. 1978 Jan;19(1):19–26. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R., Lydeard S. Prevalence of symptoms of dyspepsia in the community. BMJ. 1989 Jan 7;298(6665):30–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6665.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata J. H., Haile B. M., Elashoff J. D. Sex differences in peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1985 Jan;88(1 Pt 1):96–100. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langman M. J. What is happening to peptic ulcer? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982 Apr 10;284(6322):1063–1064. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6322.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell D. C., Gage H. G., Robinson N. A. Symptoms in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1971 Jan;21(102):32–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PULVERTAFT C. N. Peptic ulcer in twon and country. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1959 Jul;13:131–138. doi: 10.1136/jech.13.3.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker P., Luther J., Samloff I. M., Feldman M. Life events stress and psychosocial factors in men with peptic ulcer disease. II. Relationships with serum pepsinogen concentrations and behavioral risk factors. Gastroenterology. 1988 Feb;94(2):323–330. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt R., Katschinski B., Logan R., Ashley J., Langman M. Rising frequency of ulcer perforation in elderly people in the United Kingdom. Lancet. 1986 Mar 1;1(8479):489–492. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir R. D., Backett E. M. Studies of the epidemiology of peptic ulcer in a rural community: prevalence and natural history of dyspepsia and peptic ulcer. Gut. 1968 Feb;9(1):75–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.9.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]