Abstract

Protein degradation by the ubiquitin (Ub) system controls the concentrations of many regulatory proteins. The degradation signals (degrons) of these proteins are recognized by the system's Ub ligases (complexes of E2 and E3 enzymes). Two substrate-binding sites of UBR1, the E3 of the N-end rule pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, recognize basic (type 1) and bulky hydrophobic (type 2) N-terminal residues of proteins or short peptides. A third substrate-binding site of UBR1 targets CUP9, a transcriptional repressor of the peptide transporter PTR2, through an internal (non-N-terminal) degron of CUP9. Previous work demonstrated that dipeptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues allosterically activate UBR1, leading to accelerated in vivo degradation of CUP9 and the induction of PTR2 expression. Through this positive feedback, S. cerevisiae can sense the presence of extracellular peptides and react by accelerating their uptake. Here, we show that dipeptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues cause dissociation of the C-terminal autoinhibitory domain of UBR1 from its N-terminal region that contains all three substrate-binding sites. This dissociation, which allows the interaction between UBR1 and CUP9, is strongly increased only if both type 1- and type 2-binding sites of UBR1 are occupied by dipeptides. An aspect of autoinhibition characteristic of yeast UBR1 also was observed with mammalian (mouse) UBR1. The discovery of autoinhibition in Ub ligases of the UBR family indicates that this regulatory mechanism may also control the activity of other Ub ligases.

Keywords: proteolysis, N-end rule, autoinhibition, E3, yeast

Ubiquitin (Ub) is conjugated to other proteins through the action of three enzymes, E1, E2, and E3 (1–4). A ubiquitylated protein substrate that is targeted for degradation bears a covalently linked multi-Ub chain, which mediates the binding of substrate by the 26S proteasome, an ATP-dependent protease (5). The selectivity of ubiquitylation is determined by E3, which recognizes a substrate's degradation signal (degron; refs. 3 and 6–9). The term “Ub ligase” denotes either an E2-E3 complex or its E3 component. One Ub-dependent proteolytic pathway, called the N-end rule pathway, targets proteins bearing destabilizing N-terminal residues (10–17). The corresponding degron, called the N-degron, consists of a substrate's destabilizing N-terminal residue and an internal lysine residue (18, 19). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the 225-kDa, RING domain-containing Ub ligase UBR1 recognizes primary destabilizing N-terminal residues of two types: basic (type 1: Arg, Lys, and His) and bulky hydrophobic (type 2: Phe, Leu, Tyr, Trp, and Ile; ref. 11). Several other N-terminal residues function as tertiary (Asn, Gln) and secondary (Asp, Glu) destabilizing residues, in that they are recognized by UBR1 after their enzymatic conjugation to Arg, a primary destabilizing residue (17, 20). In the case of N-terminal Asn and Gln (and also Cys in metazoans), this conjugation is preceded by other enzymatic modifications (17, 21, 22). Dipeptides bearing either basic (type 1) or bulky hydrophobic (type 2) N-terminal residues have been shown to inhibit degradation of N-end rule substrates through competition with substrates for binding to the type 1 or type 2 sites of UBR1 (13, 14, 20, 23).

The emerging physiological roles of the N-end rule pathway have been reviewed (11, 13, 15–17, 22, 24, 25). One function of the S. cerevisiae N-end rule pathway is the control of peptide import through regulated degradation of the 35-kDa homeodomain protein CUP9, a transcriptional repressor of the di- and tripeptide transporter PTR2 (13, 24, 25). CUP9 contains an internal (C terminus-proximal) degron which is recognized by a third substrate-binding site of UBR1. Previous work (13) has shown that the UBR1-dependent degradation of CUP9 is allosterically activated by dipeptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues. In the resulting positive feedback, imported dipeptides bind to UBR1 and accelerate the UBR1-dependent degradation of CUP9, thereby derepressing the expression of PTR2 and increasing the cell's capacity to import peptides (13).

Here, we address the mechanism through which dipeptides that bind to UBR1 accelerate the degradation of CUP9. We discovered that this mechanism involves autoinhibition of UBR1.

Materials and Methods

Extracts of S. cerevisiae Expressing UBR1 or Its Derivatives.

N-terminally flag-tagged (26), full-length S. cerevisiae UBR1 (fUBR1) and its truncated derivatives were expressed in S. cerevisiae from the PADH1 promoter in a high-copy plasmid, followed by preparation of an extract containing fUBR1 or its derivatives.

GST-Pulldown Assay.

DNA fragments encoding either WT CUP9, its mutant derivatives, RAD6, the 273-residue C-terminal fragment of S. cerevisiae UBR1 (UBR11678–1950), or the 259-residue C-terminal fragment of mouse UBR1 (mUBR11499–1757) were subcloned into pGEX-2TK (Amersham Pharmacia), downstream of and in frame with the ORF of GST. The final constructs (except the one containing RAD6) also bore the C-terminal His-6 tag (26). The resulting plasmids were expressed in Escherichia coli, and the corresponding proteins were purified by affinity chromatography with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen). GST-pulldown assays with S. cerevisiae extracts containing fUBR1 or its derivatives were carried out as described (27).

Pulldown Assay with Peptide Beads.

12-mer peptides, XIFSTDTGPGGC (in single-letter abbreviations for amino acids), with the N-terminal residue X being Arg, Phe, Gly, Ser, Thr, Ala, or Asp, were crosslinked via its C-terminal Cys residue to UltraLink Iodoacetyl beads (Pierce), followed by a pulldown assay carried out similarly to GST-pulldowns with S. cerevisiae extracts containing the overexpressed, full-length S. cerevisiae fUBR1.

Pulse–Chase Assay.

Ub fusion proteins of the UPR (Ub/protein/reference) technique (19, 28) were expressed in S. cerevisiae from low-copy plasmids and the PMET25 promoter. Upon cotranslational cleavage by deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs), these fDHFR-Ub-CUP9f fusions yielded the long-lived reference protein flag-dihydrofolate reductase-Ub (fDHFR-Ub) and either the C-terminally flag-tagged WT CUP9 (CUP9f) or its mutant derivatives. Pulse-chases were carried out essentially as described (13, 15, 19). See Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Results and Discussion

Pairs of Type 1 and Type 2 Dipeptides Greatly Increase the Apparent Affinity of UBR1 for CUP9.

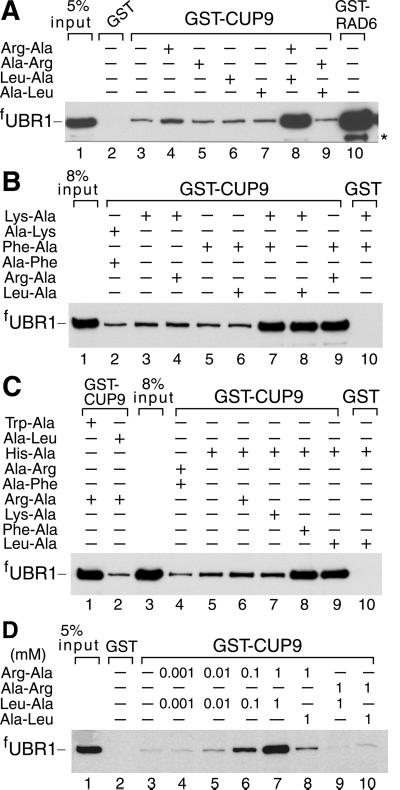

UBR1-CUP9 interactions were examined by using GST-pulldown assays. Equal amounts of extract from S. cerevisiae overexpressing flag-tagged UBR1 (fUBR1) were incubated in either the absence or presence of various dipeptides (at 1 mM) with glutathione-Sepharose beads preloaded with GST-CUP9. The bound proteins were eluted, fractionated by SDS/PAGE, and the bound fUBR1 was assessed by immunoblotting. The cognate Ub-conjugating (E2) enzyme RAD6 (GST-RAD6), a known UBR1 ligand (12), bound to fUBR1, whereas GST alone did not, in either the presence or absence of dipeptides (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 10; Fig. 1B, lane 10; Fig. 1C, lane 10). In the absence of added dipeptides or in the presence of dipeptides with stabilizing N-terminal residues, such as Ala-Arg or Ala-Leu, fUBR1 exhibited a detectable but weak binding to GST-CUP9 (Fig. 1A, lanes 3, 5, and 7). This binding was slightly but reproducibly increased in the presence of Arg-Ala, a type 1 dipeptide, but not in the presence of Leu-Ala, a type 2 dipeptide (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 and 6 vs. lanes 3, 5, and 7). Remarkably, the binding of fUBR1 to GST-CUP9 was greatly increased in the presence of both type 1 and type 2 dipeptides, Arg-Ala and Leu-Ala (Fig. 1A, lane 8 vs. lanes 3, 4, and 6). Other combinations of type 1 dipeptides (Lys-Ala and His-Ala) and type 2 dipeptides (Phe-Ala and Trp-Ala) yielded similar results. Specifically, a strong enhancement of the fUBR1-CUP9 interaction was observed only if both a type 1 and a type 2 dipeptide were present in the binding assay (Fig. 1 A–C). The synergistic effect of a pair of type 1 and type 2 dipeptides became detectable at 10 μM Arg-Ala plus 10 μM Leu-Ala, was strongly increased at 0.1 mM, and reached near-saturation at 1 mM Arg-Ala plus 1 mM Leu-Ala (Fig. 1D and data not shown). In contrast to type 1 and type 2 dipeptides, the corresponding free amino acids did not increase the binding of UBR1 to CUP9 in several tested combinations (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Type 1 and type 2 dipeptides, if present together, greatly increase the binding of UBR1 to CUP9. Equal amounts of an extract from S. cerevisiae overexpressing the N-terminally flag-tagged UBR1 (fUBR1) were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads preloaded with either GST alone, GST-CUP9, or with GST-RAD6, in either the presence or absence of dipeptides. The bound proteins were eluted, fractionated by SDS/PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-flag antibody. Unless otherwise stated, each dipeptide was present at 1 mM. *, Fragment of fUBR1. The “5% input” lanes refer to a directly loaded sample of the yeast extract that corresponded to 5% of the extract's amount used in the GST-pulldown assays.

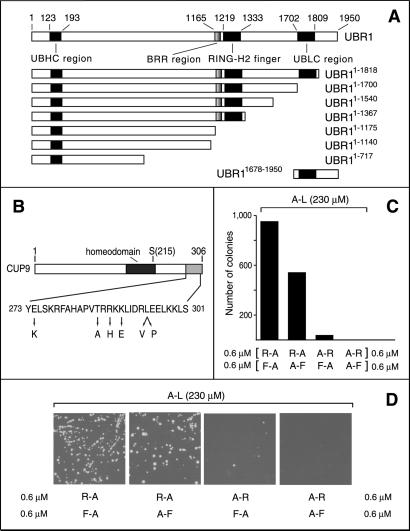

The above effect (Fig. 1) makes UBR1, operationally, a sensor for the simultaneous presence of both type 1 and type 2 dipeptides. To determine whether this property of UBR1 could be detected at the level of dipeptide uptake in vivo, we used S. cerevisiae auxotrophic for Leu. Ala-Leu, bearing a stabilizing N-terminal residue, could not rescue the strain's growth if present at 230 μM in the growth medium (Fig. 2 C and D). However, the growth was rescued if the Leu-lacking type 1 and type 2 dipeptides Arg-Ala and Phe-Ala were present together at 0.6 μM each, in addition to 230 μM Ala-Leu (Fig. 2 C and D). Under the same conditions, Arg-Ala alone (type 1 dipeptide) was significantly less effective, whereas Phe-Ala alone (type 2 dipeptide) could not rescue cell growth (Fig. 2 C and D). Because food sources of S. cerevisiae in the wild are likely to contain diverse mixtures of short peptides, the sensitivity of UBR1–CUP9 interaction to the simultaneous presence of a type 1 and a type 2 dipeptide is likely to be physiologically relevant. At higher concentrations in the medium (>2 μM), single dipeptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues were observed to stimulate the import of a nutritionally essential dipeptide bearing a stabilizing N-terminal residue (13). This may result, for example, from subthreshold in vivo levels of diverse dipeptides present in cells at all times and/or from a highly cooperative dose-response aspect of peptide import, given the circuit's positive feedback (13).

Fig 2.

S. cerevisiae UBR1, CUP9, and plating efficiency assays. (A) A diagram of S. cerevisiae UBR1, indicating the regions conserved in the fungal and metazoan UBR proteins (16, 30). His and Cys are two of the conserved residues in the UBHC region (UBR/His/Cys; residues 123–193) that encompass Gly-173 and Asp-176, which are essential for the integrity of the type 1 substrate-binding site of UBR1 (A. Webster, M. Ghislain, and A.V., unpublished data). See the main text for descriptions of the BRR, RING-H2, and UBLC regions. Also shown are the derivatives of UBR1 used in the GST-CUP9-binding assays and a fragment containing the UBLC domain (used as GST-UBR11678–1950) in the binding assay with UBR11–1140 and UBR11678–1950. UBR1 and its fragments bore N-terminal flag, except for UBR11–1140, which contained C-terminal flag. (B) A diagram of the 306-residue CUP9 highlighting its homeodomain, the site of the toxicity-reducing Asn-215→Ser mutation (13) and the C-terminal region, whose sequence is shown below together with the alterations that decreased the UBR1-dependent degradation of the corresponding CUP9 mutants in yeast (see supporting information). (C) Plating efficiency assays, carried out in minimal medium with S. cerevisiae SC295 (Leu−) in the presence of 230 μM Ala-Leu and the indicated pairs of nonnutritious dipeptides at 0.6 μM each. (D) Representative images of plates from the assays in C.

Specificity of UBR1 Interactions with CUP9 and Ligands Bearing Destabilizing N-Terminal Residues.

GST-pulldowns also were performed with metabolically stabilized CUP9 mutants (Fig. 2B) isolated through a genetic screen (F.N.-G., G. Turner, and A.V., unpublished data). All of the substitutions were located within the last 33 residues of the 306-residue CUP9, thereby defining an essential part of the CUP9 degron (Fig. 2B). An inverse correlation was observed between the in vivo half-lives of CUP9 mutants and the extent of their binding to UBR1 in GST-pulldowns (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

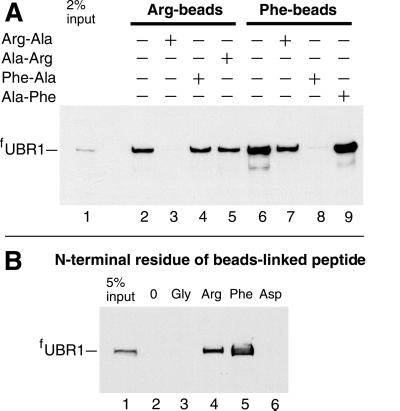

By using crosslinking and coimmunoprecipitation assays, previous work has shown that proteins bearing destabilizing N-terminal residues specifically bind to S. cerevisiae UBR1 (6). We extended this evidence through pulldown assays with synthetic 12-mer peptides of the sequence XIFSTDTGPGGC (in single-letter abbreviations for amino acids) (X = Arg, Phe, Ser, Thr, Gly, Ala, or Asp). These peptides were crosslinked to microbeads through their C-terminal Cys residue. fUBR1 bound to the 12-mer peptides bearing N-terminal Arg or Phe (type 1 and type 2 primary destabilizing residues; Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 6; Fig. 3B, lanes 4 and 5), but did not bind to the otherwise identical peptides bearing either N-terminal Gly (a stabilizing residue) or Asp (a secondary destabilizing residue; Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 6). The same results were obtained with 12-mer peptides bearing other stabilizing N-terminal residues such as Ser, Thr, or Ala.

Fig 3.

Specific binding of the S. cerevisiae ubiquitin ligase UBR1 to peptides bearing destabilizing N-terminal residues. Equal amounts of an extract from S. cerevisiae overexpressing the N-terminally flag-tagged UBR1 (fUBR1) were incubated with microbeads crosslinked to the C terminus of a 12-mer peptide XIFSTDTGPGGC (X = Arg, Phe, Ser, Thr, Gly, Ala, or Asp), followed by washes, elution of the bound proteins, SDS/PAGE, and immunoblotting with anti-flag antibody (see supporting information). (A) Lane 1: 2% of the initial extract's sample. Lanes 2–5: the binding of fUBR1 to beads-linked RIFSTDTGPGGC, bearing N-terminal Arg, in the absence of presence of specific dipeptides. Lanes 6–9: analogous assays with FIFSTDTGPGGC, bearing N-terminal Phe. (B) Lane 1: 5% of the initial extract's sample. Lanes 2–6: fUBR1 binding assay, in the absence of added dipeptides, with either mock-crosslinked beads (0) or the beads with 12-mer peptides bearing N-terminal Gly, Arg, Phe, and Asp, respectively.

At 10 mM, the added dipeptides Ala-Arg and Ala-Phe, bearing a stabilizing N-terminal residue (Ala), did not significantly inhibit the binding of UBR1 to either Arg- or Phe-bearing 12-mer peptides (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 and 9). In contrast, the Arg-Ala dipeptide abolished the binding of UBR1 to the Arg-bearing 12-mer peptide, and Phe-Ala had the same effect on the binding of UBR1 to the Phe-bearing 12-mer peptide (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 8). This inhibition was selective, in that Phe-Ala did not abolish the binding of UBR1 to Arg-bearing 12-mer peptide, and Arg-Ala did not abolish the binding of UBR1 to Phe-bearing 12-mer peptide (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 7). Similar results were obtained when mouse UBR1 (E3α) was used as a ligand in otherwise identical assays, instead of S. cerevisiae UBR1 (data not shown). No binding of UBR1 to the Gly-, Ser-, Thr-, Ala-, or Asp-bearing 12-mer peptides could be detected even after strong overexposure of autoradiograms. By a conservative estimate, the affinity of UBR1 for primary destabilizing N-terminal residues such as Arg and Phe was at least 100-fold higher than the affinity of UBR1 for stabilizing (or secondary destabilizing) N-terminal residues. The actual difference is likely to be significantly larger than 100-fold, because recent measurements using the fluorescence polarization technique and fluorescently labeled 12-mer peptides could not detect the binding of UBR1 to a Gly-bearing peptide under conditions in which UBR1 bound an otherwise identical peptide bearing N-terminal Phe with a Kd of ≈1 μM (Z.X. and A.V., unpublished data).

Recently, Baboshina et al. (29) suggested that the mammalian N-end rule pathway distinguishes between stabilizing and destabilizing N-terminal residues not through differences in the thermodynamic affinities of UBR1 (E3α) for these residues, but largely through differences in the catalytic activity of UBR1 in response to its (comparably avid) binding to either stabilizing or destabilizing N-terminal residues. This conclusion, based on the authors' interpretation of their enzymological evidence (29), is directly in conflict with both the earlier UBR1-binding data (6) and the results above. The technically straightforward, catalysis-free binding assays with yeast and mouse UBR1 (Fig. 3, and similar data with mouse UBR1 not shown) confirmed and extended the earlier evidence (6) that the specificity of N-degron's recognition stems, in the main, from large differences in the affinity of UBR1 for destabilizing vs. stabilizing N-terminal residues. Specific reasons for the incorrectness of the conclusion by Baboshina et al. (29) are unclear, save for the notion that inferences about the relative thermodynamic affinities should properly be based on assays that compare the affinities themselves, in a catalysis-free setting.

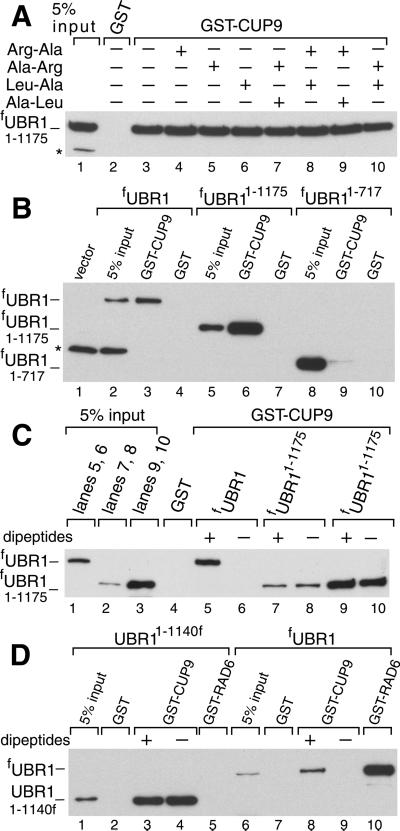

N-Terminal Half of the 225-kDa UBR1 Binds CUP9 in Either the Presence or Absence of Dipeptides.

The type 1- and type 2-binding sites of UBR1 have been mapped, using a genetic screen, to an ≈600-residue N-terminal region of the 1,950-residue UBR1 (A. Webster, M. Ghislain, and A.V., unpublished data). To locate the region of UBR1 that recognizes CUP9 (Fig. 2B), we examined the binding of GST-CUP9 to fUBR11–1175 and fUBR11–717, two N-terminal fragments of fUBR1 (Fig. 2A). (The superscript numbers refer to residue positions in the untagged WT UBR1.) These assays, carried out in the presence of 1 mM Arg-Ala plus 1 mM Leu-Ala, showed that fUBR11–1175 bound to GST-CUP9, whereas fUBR11–717 did not (Fig. 4B), indicating that sequences between residues 717 and 1175 were required for the UBR1 binding to CUP9. Both fUBR11–1175 (which bound to CUP9) and fUBR11–717 (which did not bind to CUP9) retained the capacity to bind either dipeptides or test proteins bearing destabilizing N-terminal residues (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Dipeptide-independent, high-affinity binding of CUP9 by N-terminal fragments of UBR1. (A) GST-pulldowns with fUBR11–1175 and GST-CUP9 in the presence of different dipeptides (at 1 mM each). (B) As in A, in the presence of 1 mM Arg-Ala and 1 mM Leu-Ala, with either GST alone or GST-CUP9 and either full-length fUBR1, fUBR11–1175, or fUBR11–717. (C) GST-pulldowns with either full-length fUBR1 or fUBR11–1175 in the presence of either 1 mM Arg-Ala and 1 mM Leu-Ala (+) or 1 mM Ala-Arg and 1 mM Ala-Leu (−). Two input amounts of fUBR11–1175, differing by 6-fold, were used (lanes 2 and 3). The corresponding fUBR11–1175 assays are in lanes 7 and 8 vs. 9 and 10, respectively. (D) Comparisons, in the presence of either 1 mM Arg-Ala and 1 mM Leu-Ala (+) or 1 mM Ala-Arg and 1 mM Ala-Leu (−) of the binding of fUBR1 and UBR11–1140f to either GST-CUP9 or GST-RAD6. *, Crossreacting proteins.

Remarkably, whereas strong binding of fUBR1 to GST-CUP9 required the presence of a pair of type 1 and type 2 dipeptides (Fig. 1), no such dependence was observed with the fUBR11–1175 fragment: it exhibited strong binding to GST-CUP9 under both conditions (Fig. 4A). Additional assays, using mutant CUP9 moieties, confirmed the specificity of the observed interaction, in that fUBR11–1175 and full-length fUBR1 exhibited similar patterns of affinity for the CUP9 mutants (Fig. 2 B and D and Fig. 7). fUBR11–1175 lacked the RING-H2 domain of UBR1 but contained its basic residues-rich (BRR) region (Fig. 2A). Together, these adjacent regions mediate the interaction between UBR1 and the E2 enzyme RAD6 (12). UBR11–1140f, which lacked the entire RAD6-binding site (Fig. 2A), also bound to GST-CUP9 constitutively (Fig. 4D). Thus, the CUP9-binding site and the RAD6-binding site can be separated in UBR1 fragments.

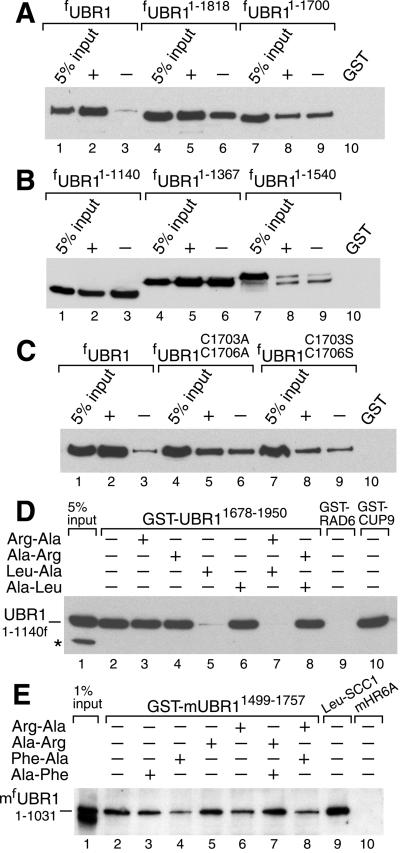

A Conserved C-Terminal Region of Yeast and Mouse UBR1 Binds to the N-Terminal Half of UBR1.

fUBR11–1367 and UBR11–1140f, which, respectively, contained and lacked the RAD6-binding site (Fig. 2A), bound to GST-CUP9 with similar affinities (Fig. 5B, lanes 4–6 vs. lanes 1–3). In contrast, both of the longer fragments, fUBR11–1540 and fUBR11–1700, exhibited weak binding to GST-CUP9 in either the presence or absence of Arg-Ala plus Leu-Ala (Fig. 5A, lanes 7–9, and Fig. 5B, lanes 7–9). The still longer fUBR11–1818 fragment, which encompassed the 108-residue, C terminus-proximal region termed UBLC (UBR/Leu/Cys; Fig. 2A; refs. 16 and 30), bound to GST-CUP9 strongly in the presence of Arg-Ala plus Leu-Ala; the omission of dipeptides decreased the binding, but to a lesser extent than with the full-length fUBR1 (Fig. 5A, lanes 4–6 vs. lanes 1–3). The UBLC domain of UBR1 (Fig. 2A; ref. 30) contains two conserved cysteines, Cys-1703 and Cys-1706. fUBR1C1703,1706S(A), two functionally inactive variants of the full-length UBR1 in which both Cys residues were converted to either Ser or Ala, exhibited a pattern of CUP9 binding similar to that of fUBR11–1700, which lacks the entire UBLC domain (Fig. 5C vs. Fig. 5A, lanes 7–9). Thus, Cys-1703 and Cys-1706 are essential for the functions of the UBLC domain.

Fig 5.

The C-terminal UBLC domain of UBR1 binds to the N-terminal region of UBR1. (A) GST-pulldowns with GST-CUP9 and either full-length fUBR1, fUBR11–1818, or fUBR11–1700 in the presence of either 1 mM Arg-Ala and 1 mM Leu-Ala (+) or 1 mM Ala-Arg and 1 mM Ala-Leu (−). (B) As in A, but with UBR11–1140f, fUBR11–1367, and fUBR11–1540. (C) As in A, but with full-length WT fUBR1 and its full-length derivatives fUBR1C1703,1706A and fUBR1C1703,1706S. (D) GST-pulldown for the interaction between UBR11–1140f and GST-UBR11678–1950 (see Fig. 2A and the main text) in the presence of different dipeptides. Lanes 9 and 10: results of analogous assays with UBR11–1140f and either GST-RAD6 or GST-CUP9. *, Crossreacting protein. (E) Lanes 1–8: as in D, but with S. cerevisiae extract containing mfUBR11–1031, the N-terminally flag-tagged N-terminal fragment of the mouse UBR1 (E3α) Ub ligase, and with GST-mUBR11499–1757, a C-terminal fragment of mouse UBR1, linked to glutathione-Sepharose beads. Lane 9: GST-pulldown with of mfUBR11–1031 and Leu-SCC1-GST, a GST fusion to a fragment of S. cerevisiae SCC1 (15) bearing N-terminal Leu, a type 2-destabilizing residue. Lane 10: mfUBR11–1031 and GST-mHR6A, one of the cognate mouse E2 enzymes that bind to full-length mUBR1 (16). Lacking the RING-H2 domain, mouse mfUBR11–1031 and yeast UBR11–1140f did not interact with the cognate E2 enzymes, mouse HR6A, and yeast RAD6 (D and E), which bind to full-length mouse and yeast UBR1s, respectively (12, 16). Mouse mfUBR11–1031 retained the substrate-binding sites, as could be demonstrated through its binding to a fragment of the S. cerevisiae SCC1 protein (15) bearing N-terminal Leu, a primary destabilizing residue (lane 9), but not to an otherwise identical SCC1 fragment bearing a stabilizing N-terminal residue (data not shown).

The type 1- and type 2-binding sites, as well as the third (CUP9-binding) site of UBR1, are located within the first ≈1,140 residues of the 1,950-residue UBR1 and precede the RAD6-binding site, which consists of the adjacent BRR and RING-H2 domains (12). As shown in Fig. 4 A, C, and D, the ≈600-residue C-terminal region of UBR1, downstream from the RING-H2 domain (Fig. 2A), is required for the suppression of CUP9 binding to UBR1 in the absence of dipeptides but is not required for the high-affinity interaction between UBR1 and CUP9. Thus, the binding of CUP9 by WT UBR1 is autoinhibited by its C-terminal region, which folds back and interacts, in part, through the UBLC domain (see below) with a region that encompasses (or is adjacent to) the CUP9-binding site of UBR1. In this “closed” conformation, steric hindrance by the C-terminal region of UBR1 precludes the binding of UBR1 to CUP9 (Fig. 6). A pair of type 1 and type 2 dipeptides synergistically relieves the autoinhibition by inducing an opening of the closed UBR1 conformation, thus abolishing the occlusion of the CUP9-binding site.

Fig 6.

Regulated autoinhibition of the ubiquitin ligase UBR1. See the main text for description of the model. The CUP9-binding site of UBR1 is denoted by “i” (a site binding to a substrate's internal degron). The RAD6-binding site is depicted in this orientation solely to indicate its constitutive availability, in contrast to the CUP9-binding site.

In the absence of type 1 and type 2 dipeptides, the probability of closed→open transition in UBR1 is small. As a result, there are few UBR1 molecules in the open conformation that are capable of binding to CUP9, thus accounting for the observed weak binding of UBR1 to CUP9 in the absence of dipeptides (Fig. 1). A pair of type 1 and type 2 dipeptides, upon their binding to the type 1 and type 2 sites of UBR1, increases the probability of closed→open transition, causing a larger fraction of UBR1 molecules to acquire the binding-competent conformation and yielding the observed strong binding to CUP9 (Fig. 6). According to this (parsimonious) model, the weak binding of UBR1 to CUP9 in the absence of a pair of type 1 and type 2 dipeptides (Fig. 1) reflects not a weak binding of CUP9 by most UBR1 molecules, but rather a low but nonzero probability of the closed→open transition in UBR1 under these conditions. In other words, the apparently weak binding of UBR1 for CUP9 in the absence of dipeptides (Fig. 1) is a manifestation of the strong binding of CUP9 by a minority of open-conformation UBR1 molecules in the largely closed-conformation UBR1 ensemble (Fig. 6).

We carried out yet another test of this model by asking whether UBR11678–1950, the 273-residue C-terminal fragment of UBR1 that contained the UBLC domain, could bind, in trans, to fUBR11–1140, the N-terminal fragment of UBR1 that contained all three of its substrate-binding sites but lacked the RAD6-binding site (Fig. 2A). fUBR11–1140 indeed bound to the UBLC-containing GST-UBR11678–1950 fragment (Fig. 5D). Remarkably, this interaction was strongly inhibited by a type 2 dipeptide (Leu-Ala) but neither by a type 1 dipeptide (Arg-Ala) nor by dipeptides with stabilizing N-terminal residues (Fig. 5D).

Mouse UBR1 (E3α), a homolog of S. cerevisiae UBR1, is a 1,757-residue Ub ligase of the N-end rule pathway, one of at least three E3s (UBR1, UBR2, and an unidentified E3) that mediate this pathway in the mouse (16, 30). We asked whether GST-mUBR11499–1757, the UBLC-containing C-terminal fragment of mouse UBR1, binds to mfUBR11–1031, the N-terminal half of mouse UBR1, similarly to the key interaction identified with yeast UBR1 (Fig. 5D). The above fragments of mouse UBR1 were indeed found to interact, and moreover, dipeptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues, in contrast to dipeptides with stabilizing N-terminal residues, inhibited the interaction of two fragments (Fig. 5E).

Regulated Autoinhibition of a Ub Ligase.

The model of autoinhibition proposed in Fig. 6 is consistent with the data of this work and explains several earlier observations as well. This model posits that the binding of Arg-Ala to the (always accessible) type 1 site of UBR1 induces a conformational change that increases the accessibility (and/or affinity) of the type 2-binding site to Leu-Ala. It is the latter binding event that induces the closed→open transition in UBR1 and the unmasking of its CUP9-binding site. In addition to accounting for the fact that both type 1 and type 2 dipeptides must be present together for a strong increase in the binding of full-length UBR1 to CUP9 (Fig. 1), this sequential-binding mechanism is also consistent with the finding that a type 2 dipeptide alone, but not a type 1 dipeptide alone, is sufficient for abolishing the binding of the UBLC-containing C-terminal fragment UBR11678–1950 to the N-terminal fragment UBR11–1140 (Fig. 5D). Specifically, whereas the binding of a type 1 dipeptide increases the accessibility of the type 2-binding site in the full-length UBR1, the type 2 site is likely to be always accessible in the complex of UBR11–1140 with UBR11678–1950, because UBR11678–1950 contains the UBLC domain but not the entire C-terminal region of UBR1 (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the sequential-binding mechanism (Fig. 6) also accounts for two earlier findings: that type 1 dipeptides accelerate the degradation of type 2 protein substrates by the N-end rule pathway, whereas type 2 dipeptides do not accelerate the degradation of type 1 substrates (16, 20, 23).

Neither the full-length fUBR1C1703,1706S(A) mutants nor the fUBR11–1700 fragment of WT UBR1 that lacked the UBLC domain could rescue the N-end rule pathway in ubr1Δ S. cerevisiae, even upon overexpression (data not shown). Thus, the C terminus-proximal UBLC domain (Fig. 2A) performs yet another, currently unknown in vivo function, in addition to making possible the closed conformation of UBR1 (Fig. 6). One possibility is that the UBLC domain might be the site of a Ub∼UBR1 thioester. Although UBR1 and other E3s of the RING-domain family are presumed not to form Ub∼E3 thioesters, in contrast to the HECT-domain family of E3s (2, 3), the possibility of a functionally relevant Ub thioester in a RING-containing E3 remains to be precluded definitively, at least with UBR1.

Autoinhibition is an essential feature of many regulatory proteins, including protein kinases and phosphatases (31, 32), nitric oxide synthases (33), transcription factors (34), and regulators of actin polymerization (35–37). The synergistic activation of the UBR1–CUP9 interaction through the binding of both type 1 and type 2 dipeptides to UBR1 (Fig. 6) is an example of positive signal integration by a regulatory protein, a property that approximates a logical AND gate. Among the previously described proteins whose input–output patterns approximate an AND gate are N-WASP, a regulator of actin polymerization, and the cell cycle-regulating CDK kinases (reviewed in ref. 38).

Autoinhibition has not been reported for Ub ligases. UBR1, UBR2, and UBR3, the mouse homologs of S. cerevisiae UBR1, contain the conserved UBHC, RING-H2, and UBLC domains (Fig. 2A, and refs. 16 and 30). In addition, mouse UBR1 and UBR2 contain binding sites for the type 1- and type 2-destabilizing N-terminal residues. Moreover, the functional properties of these sites in mouse UBR1 and UBR2, such as the ability of type 1 dipeptides to stimulate the degradation of type 2 N-end rule substrates, are also similar to those of yeast UBR1 (16, 20, 23). Finally, an aspect of autoinhibition characteristic of yeast UBR1 was also observed with mouse UBR1 (Fig. 5E). Thus, it is highly likely that metazoan E3s of the UBR family also are controlled through autoinhibition, similarly to yeast UBR1. The S. cerevisiae UBR2 E3 and mouse UBR3 E3, whose functions remain unknown, are not a part of the N-end rule pathways in the respective organisms (H. Rao, T.T., Y. T. Kwon, and A.V., unpublished data). Thus, the (postulated) autoinhibition of yeast UBR2 and mouse UBR3 may be regulated by naturally occurring small compounds distinct from dipeptides. Identifying these compounds will provide a clue to still unknown physiological roles of the UBR-family Ub ligases that function outside the N-end rule pathway.

The discovery of autoinhibition in the Ub ligases of the UBR family indicates that this regulatory mechanism may control the activity of other Ub ligases as well. Our findings also suggest that natural compounds (either small molecules or proteins) may regulate the activity of diverse Ub-dependent pathways through the suppression or induction of autoinhibition in Ub ligases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. A. Johnston, S. W. Stevens, and A. Webster for strains and plasmids, S. Horvath and her colleagues for the synthesis of peptides, and G. C. Turner, A. Webster, and M. Ghislain for permission to cite unpublished data. We thank former and current members of the Varshavsky laboratory, particularly G. C. Turner and H. Rao, for discussions and advice, and G. C. Turner for his comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK39520 and GM31530 (to A.V.). F.N.-G. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Spanish Ministry of Education, the Fulbright Foundation, and the Del Amo-UCM Foundation.

Abbreviations

Ub, ubiquitin

References

- 1.Hershko A., Ciechanover, A. & Varshavsky, A. (2000) Nat. Med. 10, 1073-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman A. M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickart C. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conaway R. C., Brower, C. S. & Conaway, J. W. (2002) Science 296, 1254-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwickl P., Baumeister, W. & Steven, A. (2000) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10, 242-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartel B., Wünning, I. & Varshavsky, A. (1990) EMBO J. 9, 3179-3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshaies R. J. (1999) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 435-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng N., Schulman, B. A., Song, L., Miller, J. J., Jeffrey, P. D., Wang, P., Chu, C., Koepp, D. M., Elledge, S. J., Pagano, M., et al. (2002) Nature 416, 703-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters J.-M. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 931-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachmair A., Finley, D. & Varshavsky, A. (1986) Science 234, 179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varshavsky A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 12142-12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie Y. & Varshavsky, A. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 6832-6844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner G. C., Du, F. & Varshavsky, A. (2000) Nature 405, 579-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davydov I. V. & Varshavsky, A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22931-22941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao H., Uhlmann, F., Nasmyth, K. & Varshavsky, A. (2001) Nature 410, 955-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon Y. T., Xia, Z., Davydov, I. V., Lecker, S. H. & Varshavsky, A. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 8007-8021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon Y. T., Kashina, A. S., Davydov, I. V., Hu, R.-G., An, J. Y., Seo, J. W., Du, F. & Varshavsky, A. (2002) Science 297, 96-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachmair A. & Varshavsky, A. (1989) Cell 56, 1019-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki T. & Varshavsky, A. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 6017-6026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonda D. K., Bachmair, A., Wünning, I., Tobias, J. W., Lane, W. S. & Varshavsky, A. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 16700-16712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker R. T. & Varshavsky, A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12065-12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon Y. T., Balogh, S. A., Davydov, I. V., Kashina, A. S., Yoon, J. K., Xie, Y., Gaur, A., Hyde, L., Denenberg, V. H. & Varshavsky, A. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4135-4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker R. T. & Varshavsky, A. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 2374-2378. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alagramam K., Naider, F. & Becker, J. M. (1995) Mol. Microbiol. 15, 225-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrd C., Turner, G. C. & Varshavsky, A. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Smith, J. A., Seidman, J. G. & Struhl, K. (2002) (Wiley Interscience, New York).

- 27.Xie Y. & Varshavsky, A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2497-2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner G. C. & Varshavsky, A. (2000) Science 289, 2117-2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baboshina O. V., Crinelli, R., Siepmann, T. J. & Haas, A. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39428-39437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwon Y. T., Reiss, Y., Fried, V. A., Hershko, A., Yoon, J. K., Gonda, D. K., Sangan, P., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A. & Varshavsky, A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7898-7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soderling T. R. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 1823-1826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu W., Doshi, A., Lei, M., Eck, M. J. & Harrison, S. C. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 629-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishida C. R. & Ortis de Montellano, P. R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14692-14698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim W. Y., Sieweke, M., Ogawa, E., Wee, H. J., Englmeier, U., Graf, T. & Ito, Y. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 1609-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohatgi R., Ho, H. H. & Kirschner, M. (2000) J. Cell. Biol. 150, 1299-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prehoda K. E., Scott, J. A., Mullins, R. D. & Lim, W. A. (2000) Science 290, 801-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weaver A. M., Heuser, J. E., Karginov, A. V., Lee, W., Parsons, J. T. & Cooper, J. A. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1270-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prehoda K. E. & Lim, W. A. (2002) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 149-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.