Abstract

The cytokine hormones prolactin and erythropoietin mediate tissue-specific developmental outcomes by activating their cognate receptors, prolactin receptor (PrlR) and erythropoietin receptor (EpoR), respectively. The EpoR is essential for red blood cell formation, whereas a principal function of PrlR is in the development of the mammary gland during pregnancy and lactation [Ormandy, C., et al. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 167–178]. The instructive model of differentiation proposes that such distinct, cytokine-dependent developmental outcomes are a result of cytokine receptor-unique signals that bring about induction of lineage-specific genes. This view was challenged by our finding that an exogenously expressed PrlR could rescue EpoR−/− erythroid progenitors and mediate their differentiation into red blood cells. Together with similar findings in other hematopoietic lineages, this suggested that cytokine receptors do not play an instructive role in hematopoietic differentiation. Here, we show that these findings are not limited to the hematopoietic system but are of more general relevance to cytokine-dependent differentiation. We demonstrate that the developmental defect of PrlR−/− mammary epithelium is rescued by an exogenously expressed chimeric receptor (prl-EpoR) containing the PrlR extracellular domain joined to the EpoR transmembrane and intracellular domains. Like the wild-type PrlR, the prl-EpoR rescued alveologenesis and milk secretion in PrlR−/− mammary epithelium. These results suggest that, in cell types as unrelated as erythrocytes and mammary epithelial cells, cytokine receptors employ similar, generic signals that permit the expression of predetermined, tissue-specific differentiation programs.

Tissue differentiation frequently requires cytokine action. The precise role of tissue-restricted cytokine receptor signaling in tissue development, however, is not clear. It has been suggested that cytokine receptors generate instructive signals that are essential for hematopoietic differentiation (1, 2). However, this view was brought into question by several recent reports. Thus, we have expressed the prolactin receptor (PrlR), which normally plays no role in hematopoiesis, in erythropoietin receptor (EpoR−/−) erythroid progenitors, and found that it rescued these cells from death and supported their differentiation into red blood cells in vitro (3). Therefore, there is no requirement for EpoR-unique instructive signals in red cell formation. Similarly, heterologously expressed receptors rescued differentiation of c-mpl-deficient platelets and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor-mutant neutrophils (4, 5). Therefore, in hematopoietic differentiation, the role of cytokine receptors is permissive and not instructive. Here, we examine the relevance of these findings outside the hematopoietic system by assessing the role of PrlR signaling during mammary gland development in pregnancy and lactation.

Development of the mouse mammary gland occurs under control of the female reproductive hormones, estrogen, progesterone, and prolactin (Prl), largely after birth (6). A system of ducts grows outward from the nipple into the s.c. mammary fat pad. With the onset of puberty, these ducts elongate and bifurcate until they reach the edges of the fat pad (7). The ductal system continues to increase in complexity during subsequent estrous cycles and early in pregnancy through the addition of side branches. Late in pregnancy, saccular outpouchings, known as alveoli, form throughout the ductal tree (8) and differentiate into milk-secreting units.

Prl acts through the PrlR to induce its multiple effects. PrlR−/− female mice are infertile because of numerous reproductive defects (9) affecting ovarian function and the uterus; these in turn affect mammary morphogenesis in multiple ways. For this reason, a transplantation model was used to define the specific role of the PrlR in mammary gland development (10, 11). As has been shown repeatedly, this transplantation technique makes it possible to engraft wild-type mammary epithelial cells (MECs) into a mammary fat pad that had been cleared of endogenous epithelium; the engrafted cells can then organize and form an entire new mammary epithelial tree (12). This transplantation technique made it possible for us to introduce PrlR−/− MECs into a wild-type host and to determine the localized effects on the mammary epithelium of receptor deletion without the confounding effects of the systemic hormonal alterations seen in PrlR−/− animals.

When PrlR−/− MECs were engrafted into cleared mammary fat pads of wild-type hosts, they underwent normal ductal development during puberty. However, during pregnancy, the PrlR−/− MECs failed to form alveoli and to differentiate into milk-secreting cells (10). These observations indicated that although the PrlR expressed in MECs is not required for the earlier steps of mammary morphogenesis, it mediates an essential, cell-autonomous function in MEC differentiation and alveologenesis during pregnancy and lactation.

Here, we have investigated whether the signaling domain of the distantly related EpoR could, when coupled with the ligand-binding domain of the PrlR, rescue the defective alveologenesis and differentiation of PrlR−/− MECs.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

PrlR+/− mice were maintained on C57Bl6 × 129SV background. Genotyping for PrlR was carried out by PCR on tail DNA as described (9).

Three-week-old F1 females of 129SV × C57Bl6 crosses were used as recipients. Their inguinal mammary glands were surgically cleared of the endogenous epithelium as described (12). The mice were mated 6 weeks after transplantation, and the engrafted glands were analyzed, together with control unmanipulated glands from the same mouse, by wholemount microscopy. For histological analysis they were subsequently embedded in paraffin and 8-μm sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or, alternatively, processed for immunohistochemistry as described (13).

Mammary Gland Wholemounts.

The glands were dissected, spread onto a glass slide, fixed in a 1:3 mixture of glacial acetic acid/100% ethanol, hydrated, stained overnight in 0.2% carmine (Sigma) and 0.5% AlK(SO4)2, dehydrated in graded solutions of ethanol, and cleared in 1:2 benzyl alcohol/benzyl benzoate (Sigma). Pictures were taken on a Leica MZ12 stereoscope with Kodak Ektachrome 160T.

Retroviral Supernatant.

The chimeric receptor prl-EpoR (CHI) was described (14). Prl-EpoR and PrlR were each modified by the addition of three consecutive N-terminal FLAG epitopes inserted just after the signal sequence. The addition of these FLAG epitopes did not affect receptor function (data not shown). Retroviral supernatants encoding either prl-EpoR or PrlR were generated as described (14). Briefly, VE23 cells were transiently transfected by using the calcium phosphate method, with MSCV retroviral constructs (15) each encoding the desired receptor. Culture supernatants were collected at 48 and 72 h after transfection and immediately frozen. Retroviral titers were determined by infecting primary fetal liver cells with known dilutions of each retroviral supernatant; 48 h posttransfection, expression of PrlR or prl-EpoR on the cell surface was determined by FACS analysis by using antibodies directed against the FLAG epitope. PrlR and prl-EpoR supernatants of similar titers were chosen for MEC infection.

Cell Culture.

Primary mammary epithelial cells were prepared from 10-week-old virgin female mice as described (16). Primary cells were plated on collagen-coated dishes and maintained in DMEM/F12 with insulin (10 μg/ml) and EGF (5 ng/ml).

The viral supernatants were placed on the mammary cells at day 3 of culture in the presence of 40 μg/ml polybrene and 5 ng/ml choleratoxin (17). One or 2 days later, cells were trypsinized and resuspended in PBS, and ≈0.5 × 106 cells in a 100-μl volume were injected into each cleared fat pad.

Results

Morphogenetic Effects of prl-EpoR Signaling on PrlR−/− Mammary Epithelium.

We generated a chimeric receptor (14), termed prl-EpoR, that encodes the extracellular domain of the rabbit PrlR joined in frame to the transmembrane and intracellular domains of the mouse EpoR (Fig. 1). The rabbit PrlR ectodomain was used in this instance because previous work has shown that mammalian prolactins and their receptors have broad interspecies crossreactivity. The prl-EpoR and the wild-type rabbit PrlR were each subcloned into the retroviral vector MSCV2.2 (15) and packaged in VE23 cells (14) to generate high-titer retroviral supernatants. A control retrovirus encoding LacZ was also constructed in the same viral backbone. Retroviral supernatants were used to infect primary MECs derived from either PrlR−/− or wild-type 10-week-old female mice of 129SV/C57Bl6 mixed genetic background. The resulting MEC cultures containing a mixture of infected and noninfected cells were used to reconstitute the mammary fat pads of 3-week-old prepubertal wild-type female mice whose inguinal mammary glands had been surgically cleared of endogenous epithelium. The infection efficiency was 2–5% as assessed by X-gal staining of cells infected with the LacZ control retrovirus.

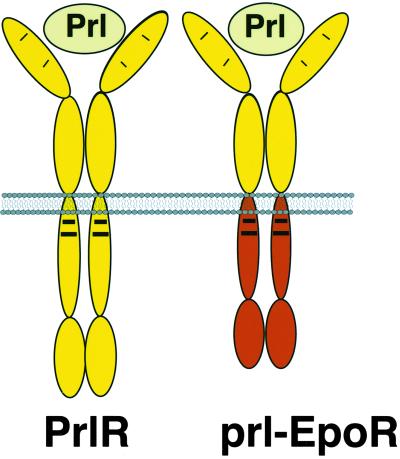

Fig 1.

Cartoon illustration of the wild-type PrlR and the chimeric receptor prl-EpoR. Both receptors contain the extracellular domain of PrlR and are activated by binding prolactin (Prl). The chimeric receptor prl-EpoR contains the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of EpoR. The receptors have <25% amino acid sequence similarity in their cytoplasmic domains. Two regions of homology, known as box 1 and box 2 regions (35), are denoted by bold lines. These regions are necessary for Jak 2 activation in both receptors. The sequences surrounding tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domains are not conserved between these receptors.

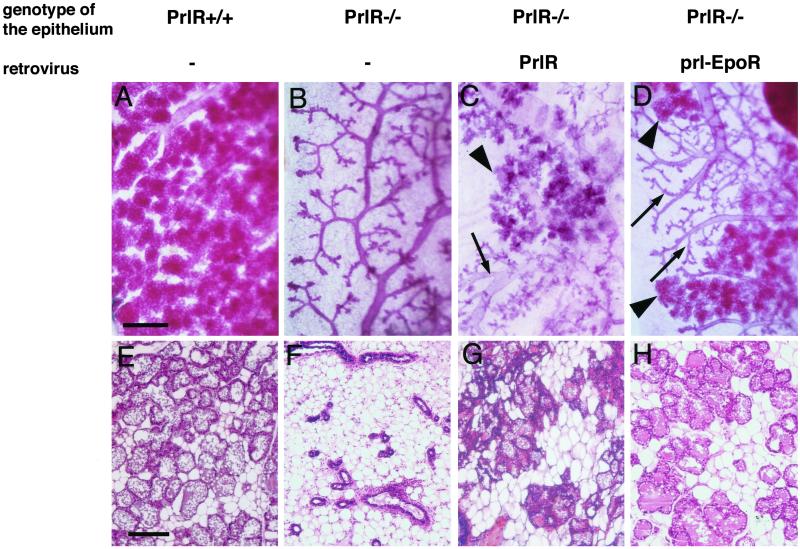

The F1 offspring of 129SV × C57Bl6 matings were used as hosts in these experiments to circumvent immunorejection, as the engrafted wild-type or PrlR−/− MECs were derived from female mice of mixed 129SV and C57Bl6 genetic backgrounds. Six weeks after surgery, the recipient female mice were mated. The engrafted mammary glands were analyzed by wholemount microscopy at the end of the resulting pregnancy, along with an unmanipulated gland from the recipient female (Fig. 2 A–D).

Fig 2.

Rescue of the PrlR−/− phenotype by wild-type PrlR and by the chimeric receptor prl-EpoR. Primary mammary epithelial cells derived from PrlR−/− female mice were infected with retrovirus expressing either PrlR or prl-EpoR. The resulting culture containing a mixture of infected and noninfected cells was subsequently engrafted into the cleared fat pads of 3-week-old F1(129SV/C57Bl6) female mice. The recipients were impregnated. Shown are wholemount preparations (A–D) and histological sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (E–H) of mammary glands harvested within a day after the recipients had given birth. (A and E) Nonmanipulated thoracic mammary gland of a wild-type host, showing extensive alveolar development. Note the secretory material and fat droplets, morphological hallmarks of secretory activity in the histological section. (B and F) Mammary fat pad engrafted with PrlR−/− MECs. The ductal system is highly branched but completely devoid of alveolar structures. There is no morphological evidence of secretory activity. (C and G) Mammary fat pad engrafted with PrlR−/− MECs rescued by infection with PrlR-encoding retrovirus. (D and H) Mammary fat pad engrafted with PrlR−/− MECs rescued by infection with Prl-EpoR-encoding retrovirus. (C and D) Areas devoid of alveolar structures as in PrlR−/− epithelial grafts (arrows) are next to areas bearing extensive alveolar structures as seen in the unmanipulated wild-type gland (arrowheads). Note that the rescued alveolar structures are distended like the ones seen in the wild-type control. (G and H) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained histological sections show the morphological hallmarks of active secretory epithelia, namely distended lumina filled with secretory material and lipid droplets as well as secretory vesicles in the cells lining the alveoli. Bars = 500 μm (A–D) and 100 μm (E–H).

Fig. 2A shows an unmanipulated, endogenous mammary gland in a recipient mouse, with the extensive alveolar development that is typical of late-stage pregnancy. As anticipated, the alveoli were fully distended, indicating that the cells lining them are differentiated and actively secreting milk products. Fig. 2B shows mammary fat pads engrafted with PrlR−/− MECs in the same animal. These cells developed into a highly branched ductal tree but completely lacked alveoli, as shown previously (10). Nineteen mammary glands were successfully reconstituted with PrlR−/− cells that had been infected with the PrlR-encoding retrovirus vector; 6 of these show alveolar development in parts of the gland (Fig. 2C). Hence, as anticipated, expression of the wild-type PrlR can rescue the morphogenetic deficit of PrlR−/− mammary epithelium. Hereafter, we refer to these PrlR−/− MECs in which normal morphogenesis has been restored as “rescued cells” and the immediately surrounding tissue as “rescued epithelium.”

Thirty-one mammary glands were successfully reconstituted with PrlR−/− cells that had been exposed to the prl-EpoR-encoding retrovirus vector. Of these, 6 glands showed alveolar development in parts of the gland (Fig. 2D), similar to that seen in glands infected with the wild-type PrlR. Infection with the control, LacZ-encoding retrovirus did not affect mammary gland morphogenesis (data not shown); thus, no restoration of alveologenesis was observed (data not shown). We concluded that prl-EpoR was indeed able to rescue the proliferative and morphogenetic defect of PrlR−/− cells. Moreover, it was able to do so with an efficiency comparable with that of the wild-type PrlR.

Differentiative Effects of prl-EpoR Signaling on PrlR−/− Mammary Epithelium.

The alveoli formed in the prl-EpoR-infected epithelium were as distended as those in wild-type glands, strongly suggesting that the cells had differentiated and were actively secreting milk. To investigate this further, we prepared histological sections from the rescued breasts (Fig. 2 E–H). The alveoli in the prl-EpoR-infected epithelium (Fig. 2H) were enlarged, indicating the presence of secretion products in the lumen. Indeed, many of the MECs lining the alveoli showed fat droplets in their cytoplasm, this being a further morphological hallmark of milk-secreting cells. As is evident from C and D in Fig. 2, the rescue by viral infection occurred only in discrete segments of the reconstituted glands, ostensibly because of the low infection rate of the primary MECs.

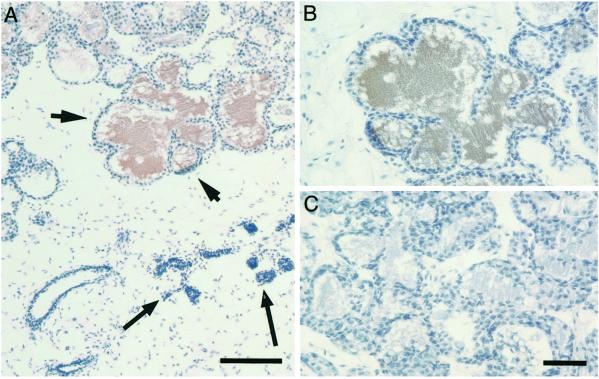

Fig. 3A shows a histological section of a chimeric gland resulting from infection with the prl-EpoR. Rescued areas showing alveoli (arrowheads) can be found next to nonrescued segments containing only ductal structures (long arrows). Immunostaining with an antibody against the milk protein β-casein revealed that the nonrescued epithelium is completely devoid of β-casein, whereas milk production occurs in the rescued cells as indicated by the brown staining. Adjacent section (Fig. 3C) processed without the primary antibody revealed no staining. Thus, signaling by EpoR rescues both the morphogenic and differentiative functions of the PrlR.

Fig 3.

Expression of the milk protein β-casein in the PrlR−/− MECs infected with prl-EpoR retrovirus. Engrafted mammary gland derived from PrlR−/− MECs infected with retrovirus encoding prl-EpoR as described in Fig. 2. (A and B) Histological sections immunostained with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the milk protein β-casein (gift of Ernst Reichmann), and counterstained with hematoxylin. Areas of alveolar development (arrowheads) are seen next to ducts devoid of alveoli (arrows). The lumina of the alveoli (A, arrowheads) stain brown because of the presence of the milk protein β-casein. A more detailed view of the distended alveoli staining positive for β-casein is shown in B. (C) Adjacent section processed without the primary anti-casein antibody, showing no staining. Bars = 100 μm (A) and 50 μm (B and C).

Discussion

PrlR−/− MECs transplanted into precleared mammary fat pads of wild-type hosts show differentiative and morphogenetic deficits in late pregnancy (10, 11). Here, we found that these deficits could be rescued by infecting PrlR−/− MECs before transplantation with retrovirus encoding the wild-type PrlR. Therefore, the PrlR mediates an essential, cell-autonomous function in MEC differentiation and alveologenesis in late pregnancy. The differentiative and morphogenetic deficits of PrlR−/− MECs could also be rescued by infecting these cells before transplantation with retrovirus encoding the chimeric receptor prl-EpoR. Although prl-EpoR contains the signaling domain of EpoR, a receptor that is not normally expressed by MECs, the extent of rescue mediated by prl-EpoR expression in PrlR−/− MECs was comparable with that seen when expressing the wild-type PrlR in these cells. The ability of prl-EpoR to successfully substitute for PrlR function during MEC differentiation shows that no PrlR-unique, instructive signals are required for this process. The essential function of PrlR in mammary gland development is therefore permissive, facilitating the differentiation of MECs along a predetermined program.

Previously, we and others have found that lineage-restricted cytokine receptors controlling the development of hematopoietic lineages do so by exerting permissive, rather than instructive, signals (3–5, 18, 19). Our findings here extend this principle beyond the hematopoietic system, suggesting it may apply widely in cytokine-dependent differentiation. Thus, although many cytokine receptors are expressed in a lineage-restricted pattern and have essential functions in the differentiation of cells of that lineage, our ability to substitute these receptors with heterologous receptors suggests that they are not the source of specificity in lineage differentiation. Instead, the specific outcome of cytokine receptor signaling in differentiation is determined by the cellular environment in which they act, rather than any unique, receptor-specific features of their intracellular signaling activities.

Many homodimeric cytokine receptors, including PrlR, EpoR, G-CSFR, and c-mpl (3–5, 18, 19), as well as the heterooligomeric granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (20) have been shown to substitute for each other's functions in tissue differentiation. This suggests that they may all signal through similar, generic signaling pathways. Indeed, all of these receptors are known to activate similar intracellular signal molecules. EpoR and PrlR are both associated with the same cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase JAK2, which chaperones the receptors to the plasma membrane (21) and becomes activated following hormone binding. Downstream of JAK2, a similar set of signaling molecules becomes activated by both PrlR and EpoR, including STAT5, PI3 kinase, PLCγ, PKC, Shc, Grb2, and Ras (22–24). The exact functions of these generic signaling pathways in tissue differentiation are not yet fully understood and probably differ between tissues. A principal function of EpoR signaling is to exert an antiapoptotic effect in early erythroblasts, in part via STAT5-dependent induction of the antiapoptotic protein bcl-xL (25, 26); bcl-xL is an essential survival factor in these cells. In contrast, bcl-xL is not required for normal mammary gland development or function, and neither the PrlR nor STAT5 affects the level of bcl-xL in mammary epithelial cells (27). Conversely, a principal function of PrlR is to bring about MEC differentiation, including the STAT5-dependent induction of milk proteins; the latter are clearly not induced in erythroid cells. How a generic signal such as STAT5 is modulated in a cell type-specific manner to bring about the induction of cell type-specific genes is at present not understood.

The cytokine receptor superfamily, and hence cytokine-dependent differentiation, emerged relatively recently in evolution, with the earliest known example described in Drosophila (28). However, conclusions similar to ours have been drawn regarding the role of the more ancient receptor tyrosine kinases in eye development in Drosophila (29). Thus, both the widely expressed Drosophila EGF receptor and the tissue-specific receptor Sevenless are present in the same photoreceptor progenitor cells and signal through the same Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cassette. Although Sevenless is essential for differentiation of photoreceptor progenitor cells into the R7 photoreceptor, the Sevenless phenotype can be rescued by expression of a constitutively active Drosophila EGF receptor (29). Thus, the specific effect of Sevenless signaling in R7 development is not due to instructive signals it generates. Instead, it results from a quantitative increase in signaling through a generic signaling cassette also activated by Drosophila EGF receptor in the same cells.

Lineage-restricted receptors such as EpoR, PrlR, or indeed the Sevenless receptor are expressed by phenotypically undifferentiated progenitor cells just before terminal differentiation. Here, we show that the specificity conveyed by primary extracellular messengers such as Epo or Prl is interpreted intracellularly according to the unique intracellular environment of these different types of progenitors. This unique cellular context is presumably a result of prior commitment to a particular cell fate. Indeed, expression of lineage-restricted cytokine receptors such as EpoR or PrlR may be a result of such commitment. The present work, together with previous studies (3–5, 18, 19), shows that signaling by cytokine receptors in committed progenitors does not alter cell fate. However, it is not clear at present whether cytokine receptors such as c-mpl, expressed by earlier, as yet uncommitted progenitors, influence the frequency of commitment to one cell lineage over another (30–32).

Cell fate decisions in early progenitors may be regulated by locally produced extracellular factors such as bone morphogenetic proteins, hedgehogs, Wnts, notch ligands, and fibroblast growth factors (33). However, because in most instances such factors are involved in the differentiation of progenitors of many different lineages, their apparently instructive effects are likely to be mediated by generic signals, with the specificity of outcome also dependent on cell context.

At present, it is not clear whether the functional similarity between homodimeric cytokine receptors might extend to heterooligomeric cytokine receptor subfamilies or, indeed, to other growth-factor receptor families such as the receptor tyrosine kinases. In at least one instance, the receptor tyrosine kinase c-fms failed to efficiently substitute for EpoR function (34). Thus, it may be that functional similarities are shared principally within receptors of the same family. Interestingly, the degree of homology in the cytoplasmic domains of homodimeric cytokine receptors is rather modest. Thus, there is <25% cytoplasmic domain amino acid sequence similarity between EpoR and PrlR (data not shown). It is therefore possible that despite their apparent functional similarity, EpoR and PrlR are each uniquely adapted to as yet unknown functions. For example, whereas the two receptors activate the same set of signal transduction proteins, they may activate specific pathways to different extents or for different periods of time. A careful quantitative comparison of PrlR and EpoR signaling was not possible by using the present experimental system, which relies on retroviral expression of the receptors. The development of mouse “knock-in” models should assist in the quantitative analysis of PrlR and EpoR function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Ormandy and Paul Kelly for the PrlR−/− mice and Ernst Reichmann for the β-casein antibody. This work was supported by a National Cancer Institute Howard Temin (KO1) Award (to M.S.), a National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Program Project Grant (to R.W.), National Institutes of Health Grant HL 32262, and a grant from Amgen Corporation (to H.F.L.). R.W. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor and a Daniel K. Ludwig Cancer Research Professor.

Abbreviations

Prl, prolactin

PrlR, Prl receptor

EpoR, erythropoietin receptor

MEC, mammary epithelial cell

References

- 1.Fukunaga R., Ishizaka-Ikeda, E. & Nagata, S. (1993) Cell 74, 1079-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metcalf D. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 11310-11314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Socolovsky M., Fallon, A. E. J. & Lodish, H. F. (1998) Blood 92, 1491-1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoffel R., Ziegler, S., Ghilardi, N., Ledermann, B., de Sauvage, F. J. & Skoda, R. C. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 698-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semerad C. L., Poursine-Laurent, J., Liu, F. & Link, D. C. (1999) Immunity 11, 153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nandi S. (1958) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 21, 1039-1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniel C. W. & Silberstein, G. B. (1987) in The Mammary Gland, ed. Daniel, C. W. (Plenum, New York), pp. 3–31.

- 8.Vonderhaar B., (1988) Breast Cancer: Cellular and Molecular Biology (Kluwer, Boston), pp. 252–266.

- 9.Ormandy C. J., Camus, A., Barra, J., Damotte, D., Lucas, B., Buteau, H., Edery, M., Brousse, N., Babinet, C., Binart, N. & Kelly, P. A. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 167-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brisken C., Kaur, S., Chavarria, T. E., Binart, N., Sutherland, R. L., Weinberg, R. A., Kelly, P. A. & Ormandy, C. J. (1999) Dev. Biol. 210, 96-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyoshi K., Shillingford, J. M., Smith, G. H., Grimm, S. L., Wagner, K.-U., Oka, T., Rosen, J. M., Robinson, G. W. & Hennighausen, L. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155, 531-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeOme K. B., Faulkin, L. J. J., Bern, H. A. & Blair, P. B. (1959) Cancer Res. 19, 511-520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brisken C., Park, S., Vass, T., Lydon, J. P., O'Malley, B. W. & Weinberg, R. A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5076-5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Socolovsky M., Dusanter-Fourt, I. & Lodish, H. F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 14009-14013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawley R. G., Lieu, F. H., Fong, A. Z. & Hawley, T. S. (1994) Gene Ther. 1, 136-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kittrell F. S., Oborn, C. J. & Medina, D. (1992) Cancer Res. 52, 1924-1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards P. A. (1996) Cancer Treat. Res. 83, 23-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Socolovsky M., Lodish, H. F. & Daley, G. Q. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6573-6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skoda R. C. (2001) Blood 98, 3504. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hisakawa H., Sugiyama, D., Nishijima, I., Xu, M.-j., Wu, H., Nakao, K., Watanabe, S., Katsuki, M., Asano, S., Arai, K.-i., et al. (2001) Blood 98, 3618-3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L. J.-s., Constantinescu, S. N. & Lodish, H. F. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 1327-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bole-Feysot C., Goffin, V., Edery, M., Binart, N. & Kelly, P. A. (1998) Endocr. Rev. 19, 225-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Constantinescu S. N., Ghaffari, S. & Lodish, H. F. (1999) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 10, 18-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Socolovsky M., Constantinescu, S. N., Bergelson, S., Sirotkin, A. & Lodish, H. F. (1998) Adv. Protein Chem. 52, 141-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Socolovsky M., Fallon, A. E. J., Wang, S., Brugnara, C. & Lodish, H. F. (1999) Cell 98, 181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Socolovsky M., Nam, H.-s., Fleming, M. D., Haase, V. H., Brugnara, C. & Lodish, H. F. (2001) Blood 98, 3261-3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walton K. D., Wagner, K. U., Rucker, E. B., 3rd, Shillingford, J. M., Miyoshi, K. & Hennighausen, L. (2001) Mech. Dev. 109, 281-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H. W., Chen, X., Oh, S. W., Marinissen, M. J., Gutkind, J. S. & Hou, S. X. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 388-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman M. (1996) Cell 87, 651-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng H., Masuko, M., Jin, L., Neff, T., Otto, K. G. & Blau, C. A. (2001) Blood 98, 328-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondo M., Scherer, D. C., Miyamoto, T., Kong, A. G., Akashi, K., Sugamura, K. & Weissman, I. L. (2000) Nature 407, 383-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pharr P. N., Ogawa, M., Hofbauer, A. & Longmore, G. D. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 7482-7486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zon L. I. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 142-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McArthur G. A., Rohrschneider, L. R. & Johnson, G. R. (1994) Blood 83, 972-981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murakami M., Narazaki, M., Hibi, M., Yawata, H., Yasukawa, K., Hamaguchi, M., Taga, T. & Kishimoto, T. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 11349-11353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]